In 1998, two auto industry giants, Daimler-Benz and Chrysler Corporation, tied the knot under the joint title of DaimlerChrysler. It was a massive coup that left the industry swooning over a marriage seemingly made in heaven. German automaker Daimler could sell more affordable cars than its Mercedes sedans, some of which cost more than $100,000. Chrysler, an American brand that sells mass-market vehicles, would finally crack the European market. Soon after DaimlerChrysler’s November 17, 1998, debut on the New York Stock Exchange, its share price peaked at $108 in January 1999. With this stamp of approval from investors, a prosperous future seemed guaranteed.

The honeymoon didn’t last long. Both companies were deeply enmeshed in their own way of doing business, and their cultural incompatibility soon became apparent. In cultural integration workshops at the conjoined company’s headquarters in Stuttgart, American employees were taught German formalities, such as keeping their hands out of their pockets during professional interactions. German members of Daimler’s team felt uncomfortable when their American counterparts called them by their first names, rather than by their title and last name. And while the Germans wanted thick files of prep work and a strict agenda for their team meetings, Americans approached these gatherings as a time to brainstorm and have unstructured conversations. For long-term assignments overseas, Americans were reluctant to downsize from their large suburban homes in Detroit to apartments in Stuttgart.

Integrating organizational structures was also arduous and complex. Daimler had a top-down, heavily managed, hierarchical structure devoted to precision. As a result, the company’s manufacturing operations were rigid and bureaucratic. Much like its country of origin, Daimler leaned tight. Chrysler, on the other hand, was a looser operation with a more relaxed, freewheeling, and egalitarian business culture. Chrysler also used a leaner production style, which minimized unnecessary personnel and red tape.

As these company cultures collided, Daimler faced a decision: compromise or cannibalize. It chose the latter. Daimler CEO Jürgen Schrempp had promised Chrysler CEO Robert Eaton a “merger of equals,” but his actions showed this was an acquisition rather than a merger. (Schrempp won the battle to call the new firm DaimlerChrysler rather than the alphabetical ChryslerDaimler.) Over time, Daimler dispatched a German to head Chrysler’s U.S. operations, replaced American managers with German ones, and laid off thousands of Chrysler employees, moves that fomented talk of “German invaders.” Chrysler’s dispirited employees coined a joke: “How do you pronounce DaimlerChrysler? Daimler—the Chrysler is silent.”

As the $36 billion merger began to look like an underhanded takeover, trust between these two foreign units became irreparable. Key Chrysler executives left, and after nine years of declines in stock price and employee morale, the transnational pair finally divorced in 2007.

DaimlerChrysler failed in large part due to a colossal underestimation of the tight-loose divide. Why were decision-makers so unprepared to deal with their cultural differences?

While merging with a company from another country can seem financially appealing, leaders often fail to recognize that deep-seated differences in tightness-looseness can cause significant intercultural strife. DaimlerChrysler’s disaster is all too common. When organizations considering a merger neglect to assess their cultural compatibility, they can face dire financial consequences.

Can we put an actual price tag on these failed mergers? My colleague Chengguang Li, a professor at the Ivey Business School at Western University, and I set out to test how much tight-loose rifts impact cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As). We collated information on over six thousand international M&A deals involving more than thirty different countries that occurred from 1980 to 2013. None of the mergers included in our dataset was trivial—all had a price tag above $10 million. We looked at the length of the negotiation process, the daily stock price following an M&A announcement, and the overall return on assets (ROA) over four years to determine the success of the merging companies. Finally, we determined the relative tightness or looseness of the companies’ home countries, which allowed us to measure the cultural gap between the merging pairs.

Did mergers that featured higher cultural incongruity suffer worse performance?

Yes: A substantial tight-loose gap meant costly setbacks. These mergers took longer to negotiate and finalize, had lower stock prices following the deal, and yielded much lower returns for the buyer in the deal. In fact, when there was a pronounced cultural mismatch, the acquiring company lost $30 million on average within five days of the merger’s announcement. Very large disparities caused losses of over $100 million. These effects were found even after we accounted for many other factors, including deal size, monetary stakes, industry, and geographic distance.

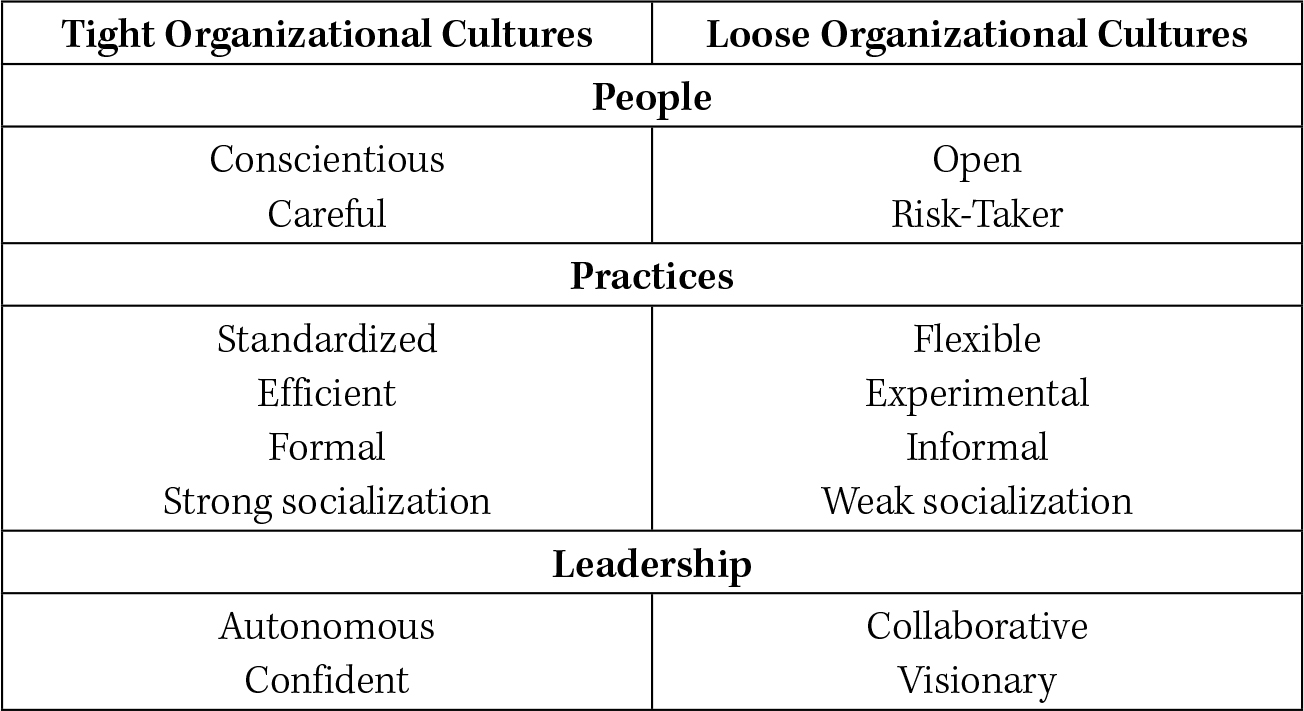

Culture is like an iceberg. Firms like Daimler and Chrysler may see value in capitalizing on each firm’s apparent strengths, but fail to realize that formidable cultural obstacles lurk beneath the surface. Because organizational norms aren’t always visible, diagnosing a company’s relative tightness or looseness requires a deep dive to understand its practices, its people, and above all, its leaders.

Consider, for example, Israel. Within the borders of this highly loose country lies the greatest concentration of tech start-ups in the world—with one start-up for nearly every two thousand Israelis. Wix, one of Israel’s most successful tech start-ups that now operates globally, has eschewed a hierarchical organizational structure, allowing employees to practice self-management. Employees need not work at individual desks or cubicles; they can share large tables in an open studio. Pet dogs roam freely. Offices are filled with an assortment of skateboards, boxing gear, and My Little Pony dolls. With rules few and far between, the atmosphere at Wix has been described as collaborative and playful, if at times chaotic. In Wix’s Vilnius office, one manager keeps a loudspeaker on hand whenever she needs to corral the attention of rowdy staff members.

Israeli companies like Wix are proof that “the people make the place.” As a “start-up nation,” Israel is full of people who are exceedingly informal and rebellious, and harbor a relentless risk-taking spirit. Jon Medved, a leading venture capitalist in Israel’s tech scene, summarizes the kind of employees attracted to the start-up scene with one Yiddish word, chutzpah, which means having “gall” or “guts.” Israelis are notably leery of being told what to do; they prefer challenging rules and guidelines over obeying them. “An outsider would see chutzpah everywhere in Israel,” explain Dan Senor and Saul Singer, authors of Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle, “in the way university students speak with their professors, employees challenge their bosses, sergeants question their generals, and clerks second-guess government ministers. To Israelis, however, this isn’t chutzpah, it’s the normal mode of being.”

To level the playing field, Israelis often call people in positions of authority by a diminutive (former prime minister Ariel Sharon was called “Arik”), or even by cheeky nicknames: six-foot-six-inch Moshe Levi, a chief of staff to Israel’s military, went by the nickname “Moshe VeHetzi,” or “Moshe and a half.” Israeli tech blogger and entrepreneur Hillel Fuld explains how this culture-wide disobedience fuels the country’s immense growth in start-ups: “The unwillingness to merge, whether on the highway or in business, is the same character that drives the world of innovation.” Moreover, many Israelis love to take risks. Wix president and COO Nir Zohar joined the start-up team in its early days because he was attracted to the uncertainty and adventure that came with the project. “It was very exciting to go and do something completely new, to start from scratch, to take that risk,” Zohar told the podcast Startup Camel. In a positive feedback loop, Israel boasts citizens with loose mind-sets who like to create loose businesses, where they perpetuate loose practices.

Of course, Israel doesn’t have the market cornered on loose workplaces. In the United States, the loose state of California proved to be the perfect breeding ground for start-ups like Apple, Facebook, Google, and thousands more, outcompeting each other to offer employees unprecedented freedom and unconventional comforts (including anything from video arcade rooms, minibars, massages, and free cooking classes). And in loose New Zealand, office life at game-designing studio RocketWerkz is rambunctious. Employees are given unlimited paid leave so they can freely manage their work around their personal lives—no questions asked. If a pet dies or a relationship ends, they can guiltlessly skip work and tend to their broken hearts. But unusual perks may also lure them to the office, such as visits from stress-reducing kittens.

Now imagine companies from Israel or New Zealand, with their unbridled practices and people, merging with those from Singapore, where great formality, precision, and discipline permeate organizations. In business interactions, people show respect for the organizational hierarchy. Workers dress modestly and business cards are expected to be received with both hands as a sign of respect. Criticism of one’s boss is taboo. Business settings are particularly tight in Singapore because work is an integral component of national identity. To compete effectively in regional markets, Singapore grew to adopt an intense work-centric culture. Indeed, while Singapore has a knack for quickly scaling up its business ventures, Israel has struggled to do so. “What Israelis have not done so well is grow their companies into the big leagues,” reporter John Reed writes for the Financial Times, due to “a restless, risk-friendly culture of serial entrepreneurship” that has “favored quick exits over organic growth.”

In their comparison of the two countries, authors Dan Senor and Saul Singer explain how Singapore “differs dramatically” from Israel. Singapore’s focus on order and insistence on obedience, reflected in the country’s immaculately clean streets and well-manicured lawns, contrast with the litter and trash you’re more likely to see in the public spaces and front yards of Tel Aviv. Singapore’s society-wide emphasis on order certainly has its perks, but it can generally lead corporations “to sacrifice flexibility for discipline, initiative for organization, and innovation for predictability,” according to the authors. Israeli organizations may lack Singapore’s order and discipline, but they’re more likely to be nimble and innovative. This is the tight-loose trade-off in action.

Japanese organizations are also generally known for their many rules, formality, and hierarchy. For years, Toyota has operated under a traditional pyramid structure with many standardized processes. Employees shun conflict, and conservative business suits and complex bowing protocols are de rigueur. As part of their intensive orientation, new employees at Toyota are taught company history and have to fully master the “Toyota Way.” And at the Japanese electronics corporation Panasonic, the workday starts with group calisthenics, singing the official company song, and chanting the company’s “Seven Commandments.”

Over in Korea, Samsung’s onboarding process has been compared to a military boot camp, with sleep-deprived trainees memorizing every detail of the firm’s history and learning to conform to its demanding corporate culture. Koreans face collective pressure to cooperate with social customs and formalities—conveyed with the Korean word nunchi, which describes one’s ability to pick up on norms. Those who lack nunchi may be harshly criticized. “You have to fall in line,” one former Samsung employee told Bloomberg Businessweek. “If you don’t, the peer pressure’s unbearable. If you can’t follow a specific directive, you can’t stay at the firm.”

The formalities and norms found in Japanese and Korean organizations mirror their national cultures’ strong emphases on discipline and traditional structures, features that developed over centuries in response to threat. Modern-day Korean workplaces remain highly influenced by their country’s 2,500-year adherence to Confucian teachings, which emphasize the importance of obedience and discipline for a well-functioning society. In both Japanese and Korean society, an emphasis on respecting convention and following rules has helped create organizations prized for their efficiency and precision.

Tight-loose organizational contrasts can be seen beyond East and West. After noticing a spike in recent years of businesses relocating from tight Norway to loose Brazil, Thomas Granli from the University of Oslo conducted in-depth interviews with Brazilian and Norwegian team members to assess differences in work styles. The jeitinho Brasileiro, or “Brazilian way,” refers to the common habit of bypassing formal customs and laws to get things done. This “beat the system” mentality can play out as cutting lines, finding legal loopholes, interrupting others, and devising ingenious life hacks. Meanwhile, the Brazilian version of “don’t worry”—fique tranquilo—is a commonly used phrase, and it carries over from work time to play time. In an effort to spur employee motivation, Brazilian portfolio management firm Semco Partners has embraced one rule, which is to radically abandon all rules. Semco employees get to pick their own schedules, wages, holidays, evaluators, and overarching work goals.

Not surprisingly, tight cultures like Norway that do business in Brazil can struggle. Interviewees in Granli’s study agreed, for instance, that Norwegians stressed punctuality, while Brazilians didn’t. “Time has a lower priority in Brazil,” one Norwegian said. “[Here] the deadlines need to be pushed more than home; things are done at the last minute.” But if they tended to be tardy, Brazilian employees were also described as more flexible. Norwegians are sticklers for standard operating procedures; Brazilians embrace fluidity. This led one Brazilian manager to comment, “On a day to day basis, Norwegians are more efficient, but when the time comes to act, Norwegians are slow.”

Tight and loose organizations can seem like different universes, and their leaders personify this divergence. In the Daimler-Chrysler merger, a large cultural rift sprang up due to the companies’ contrasting leadership styles. At Daimler, which revered work formalities, all business decisions came from top executives. “Anyone who isn’t sure about what is and isn’t allowed can find out by asking his or her supervisor,” Daimler chairman Dieter Zetsche told 360° magazine in 2009, after the firms separated. “Every employee must make sure his or her behavior is correct. And I expect our managers to set a good example.” By contrast, Chrysler’s executives often granted mid-level managers the ability to oversee their own projects, unconstrained from above. These irreconcilable leadership styles became the final nail in the coffin.

Leaders aren’t born fully formed; they’re raised with certain cultural mandates. The same leadership style that is revered in one culture can be the source of disdain in another. In the largest study ever done on leadership, a team of researchers known as GLOBE (short for Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) recruited over seventeen thousand managers spanning over nine hundred organizations across sixty countries to assess their beliefs about what makes a leader effective. Which qualities mattered most? Acting independently? Working collaboratively? Being a visionary? In my own analysis of its dataset, I wanted to see the types of leaders that people in tight and loose cultures perceived to be effective.

True to form, they were opposite. People in loose cultures prefer visionary leaders who are collaborative. They want leaders to advocate for change and empower their workers. Ricardo Semler, CEO of Brazil’s Semco Partners, exemplifies this leadership style. He’s worked hard to get out of the way so that others may step up and innovate. “Our people have a lot of instruments at their disposal to change directions very quickly, to close things, and open new things,” Semler has said. “If we said there’s only one way to do things around here and tried to indoctrinate people, would we be growing this steadily? I don’t think so.” In fact, it’s hard to pinpoint if any single employee is in charge at Semco. All workers are taught how to read balance sheets, so the whole group—from the most senior analysts to cleaning crew members—can make informed votes on all company-wide decisions. Semler described an occasion when his employees vetoed an acquisition that he wanted to pursue: “I’m still sure we should have bought [the company]. But they felt we weren’t ready to digest it, and I lost the vote.” Although disappointed, Semler reasoned, “Employee involvement must be real, even when it makes management uneasy.”

Organizational leaders in many Israeli companies go even further, intentionally fostering a culture of disagreement. “The goal of a leader should be to maximize resistance—in the sense of encouraging disagreement and dissent,” explains Dov Frohman, founder of Intel Israel. “If you aren’t aware that the people in the organization disagree with you, then you are in trouble.”

The types of leaders preferred in tight cultures are dramatically different. People in tight cultures view effective leaders as those who embody independence and great confidence—that is, as people who like to do things their own way and don’t rely on others, my analyses of the GLOBE study showed. That leadership style can be found at the Chinese firm Foxconn, a major supplier of electronics to companies like Apple, Sony, and Dell. Founded in 1974 by Terry Gou, Foxconn is one of China’s largest exporters and employs over 1.2 million people. Gou has described his leadership philosophy as “decisive,” and he views good leadership as “a righteous dictatorship.” Valuing discipline and obedience among his workers, Gou executes command-and-control management within a rigidly hierarchical company. At Foxconn, mid-level managers model Gou’s style by being forceful and autocratic, maintaining a clear power distance between themselves and low-level employees.

These examples all attest to the fact that there are large cross-national differences in the people, practices, and leaders in organizations. Tight organizations boast great order, precision, and stability, but have less openness to change. Loose organizations have less discipline and reliability, but compensate with greater innovation and appetite for risk. With these differences evolving from such powerful forces, it’s not difficult to see why merging organizations from tight and loose nations is risky business.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s O*Net database provides a gold mine of descriptions of jobs in as many industries as you can imagine. From karate instructor to nuclear plant operator, from graphic designer to short order cook, this rich data source provides scores of details on thousands of jobs, including the tasks performed, types of personalities needed, and typical working conditions. But hidden beneath these thousands of descriptions is an underlying structure that explains how industries differ. It all has to do with the strength of social norms.

Just as countries have practical reasons for becoming collectively tighter or looser, so do industries. Tightness abounds in industries that face threat and need seamless coordination. Sectors such as nuclear power plants, hospitals, airlines, police departments, and construction evolve into tight cultures due to their life-or-death stakes.

Take the construction industry. Balfour Beatty, one of the largest construction contractors in the United States, runs a tight ship. Like many organizations in the construction industry, it’s responsible for handling the logistics, hiring, and design details of complex building projects. This means its leaders must assure all their workers are safe while they perform some of the most dangerous jobs in the world. On construction sites, a single error can have grave consequences. Turning too swiftly while unloading metal pipes can critically injure nearby personnel. Machinery defects, tiny communication failures, or scaffolding that unexpectedly slips can kill workers. Due to the life-endangering risks involved in this line of work, dependability and predictability are critical, and Balfour Beatty takes this responsibility seriously. It’s much the same at construction sites around the world, which typically are subject to hazard assessments and inspections, as well as strict rules on safety, work attire, and training. Construction’s tight culture is critical for worker safety and productivity.

The military is the iconic example of tightness. In every country, armed services impose strong norms and tremendous levels of discipline on soldiers, who must be trained to brave the hardships of warfare. Cultivating well-coordinated units and absolute reverence for authority is the backbone of maintaining these strong norms. From day one, U.S. Marine recruits endure a punishing boot camp and indoctrination period that turn individual soldiers into one synchronous corps who, above all, respect their leaders. “The military is like a machine built out of hierarchy,” American marine Steve Colley told me in an interview in 2017. “And if you break the hierarchy, you’re breaking the machine.” In the course of a single day, the typical soldier is repeatedly called on to respect this hierarchical system, from the insignia on her uniform to the salutes she gives her superiors. Forgetting rules can lead to severe punishments, from an aggressive tongue-lashing to having to do hundreds of push-ups in front of one’s peers. “We have standards for things as seemingly insignificant as how we dress and as complicated as how to maintain the most advanced main battle tank in the world,” described James D. Pendry, a retired command sergeant major with the U.S. Army. “Meeting seemingly insignificant standards is as important as meeting the most complicated ones—meeting one establishes the foundation for meeting the other.”

Industries that face less threat, on the other hand, evolve to be loose. In these fields, there are benefits to changing gears quickly, instilling freedom, and thinking outside the box. Employees at the global design company Frog Design Inc., which was founded in 1969, are professionally compelled to question, provoke, self-express, and reinvent conventional tastes. Frog’s employees typically enjoy pushing boundaries. “You need to be a rebel in your heart, which means that you like to challenge and question things,” said Kerstin Feix, a former member of the company’s executive team, in a 2014 interview posted on Core77. Frog’s former director of marketing James Cortese agrees: “I’m trying to qualify what makes a frog. It’s a combination of someone who has an original point of view, but they’re also very democratic and open to new ideas.”

American online shoe retailer Zappos has the same loose ethos. Now based in Las Vegas and a subsidiary of Amazon, the firm began as a start-up and emerged as the top web-based footwear retailer by 2009. Despite its massive growth, Zappos has clung to its start-up culture and remains proudly loose to this day. The company’s bottom-up, egalitarian practices are best exemplified in its adoption of “holacracy,” a system of self-management that abolishes the traditional business hierarchy. Employees can self-organize into democratically run “circles” to meet various organizational needs on their own terms. No single person is limited to one circle or role. Everyone’s roles are fluid, and team leaders, or “lead links,” are more like friendly guides, who don’t have the authority to fire people.

Loose organizations like Frog and Zappos are characterized by highly informal, mobile, and diverse work groups. To remain successful, design companies, R&D groups, and start-ups need to always have their eye on innovating and evolving. Compared with workers in industries such as manufacturing or finance (let alone the military), employees are less restricted to their area of specialization, and the comparative lack of strong rules enables them to prosper.

Drilling down further, we see that even within the same industry, different ecological contexts can drive tight-loose differences. McKinsey and IDEO are both consulting firms, but the former work culture veers tight, while the latter leans loose. This makes sense when we consider their clients: McKinsey’s work tends to include strategy and risk assessments for corporate finance industry and government organizations, while IDEO mainly works on more creative and artistic projects for companies such as Coca-Cola and Apple. McKinsey values a hard-nosed list of company-wide objectives. Unlike IDEO consultants, McKinsey-ites have far more standardized procedures to observe at work. New hires must absorb the infamous “McKinsey way” of doing business in a rigorous training program, learning rules about how to brainstorm as a team member, make client presentations, and follow specific problem-solving steps to break down a business issue. IDEO’s loose company values, on the other hand, urge employees to “learn from failure” and “embrace ambiguity.” At IDEO, self-governing teams aren’t beholden to managers. The relaxed dress code is tied to a more laid-back interpretation of professionalism. “Just be yourself, wear whatever,” IDEO’s global head of talent, Duane Bray, has told job candidates.

Zooming in to any specific organization, we can see why certain units evolve to be tight versus loose even in the same organization. Some occupations are inherently more accountable to laws and regulations, even in the absence of physical threat—think lawyers, auditors, bankers, and government officials. These jobs are bound to high standards of professional accountability. As a result, their work unit cultures foster much stronger norms and compliance monitoring. For companies like the Big Four accounting firm Deloitte, which has a range of units with disparate work goals, the auditing unit’s culture is highly distinct from the culture found among consultants. Consultants often hustle through an unpredictable suite of projects—traveling to new places—and need to quickly acclimate to new norms that change as they juggle diverse clientele.

More and more, we see this tight-loose mix within organizations. At Ball Corporation, there’s a radically mixed work culture that combines tight manufacturing units with loose R&D divisions. Founded in the late 1800s, Ball supplies bottles and cans to some of the biggest-name brands, including Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Coors, and Budweiser. Ball is also a pioneer in aerospace technology, collaborating with NASA on spacecraft and satellites. The aerospace side includes R&D units of engineers and physicists. Due to its product development goals, this division has evolved into a loose work environment that inspires creativity with less structure and monitoring. By comparison, Ball’s manufacturing division follows a highly regimented, routinized process to expediently package and ship out millions of cans every day.

The tight-loose framework helps us make sense of differences not only between nations, but also across and within industries and even among units in the same organizations. These groups all follow a very similar logic, as shown in Figure 7.1. Think about your own employer, profession, or industry. Where is it on the tight-loose spectrum? Can you see why it might have turned out that way?

But tightness-looseness in organizations isn’t static. In today’s highly dynamic marketplace, organizations often have to adapt their cultures to fit new demands and negotiate their levels of tight and loose. This mandate can be a tall order, given deep differences in companies’ cultural DNA and the clash of people, practices, and leaders.

In the spring of 2017, I interviewed a senior leader of a large manufacturing firm headquartered in the United States. The company clearly ran a tight operation. As a publicly traded company, detailed reports and strong oversight were integral parts of its business dealings. As is typical in the manufacturing sector, employees adhered to well-defined processes and frequent evaluations to maximize their overall efficiency. The business developed core strengths of tightness, including reliable delivery and operational efficiency.

Over the firm’s eighty years, it had grown to thousands of employees worldwide. Now a multibillion-dollar operation, the company’s next step in remaining competitive was to innovate its product offerings. This meant introducing more looseness to its product development side. Although the company historically had been quite risk-averse, its leaders acquired an R&D company, primarily for its cutting-edge technology. The firm’s leaders hoped the R&D company’s agile, innovative approach would have a dynamic impact on its own culture. But soon after the acquisition was finalized, tight-loose tensions flared. While the R&D group prioritized the creation of disruptive and inventive solutions, it fell behind on team deadlines and failed to get its product to market on time. No one seemed to own any decisions, and soon the division was losing money. From the R&D team’s vantage point, the tight mother ship’s expectations were unreasonable. The new division had always worked under flexible deadlines, had little supervision, and took a long-term view—they wanted to build the most creative product possible. It was a familiar pattern establishing itself: The very qualities that the acquiring company found so appealing initially in its acquisition were causing major culture clashes.

Other companies face the opposite predicament—they face major pushback when they try to tighten. Take Microsoft in the mid-1990s. The young company’s sales were off the charts, but operations were lagging. “We had to close books at the end of the quarter to show investors and shareholders our numbers, but it always took way too long,” former Microsoft chief operating officer Bob Herbold told me in an interview. This was due to the company’s sloppy and unsystematic bookkeeping. Many of Microsoft’s subsidiary offices across the globe had developed their own rogue systems. “There was no coordination at Microsoft,” Herbold told me. “Even in marketing, nobody had a clear sense of what the brand stood for.”

The company desperately needed to inject some tightness into its operations, and Microsoft CEO Bill Gates knew it. Gates brought on Herbold so that he himself could focus on the company’s products, leaving Herbold to straighten out the business side. Wanting to preserve their looser way of working, employees first resisted Herbold’s mission of centralizing division goals and the company’s data reporting. Eventually Herbold sold them on the mission’s benefits—namely, the prospect of future profit gains—which strongly motivated them to comply. Within a year of Herbold’s business centralization, Microsoft not only saved on costs but boosted profits and its share price.

Prosperous start-ups invariably await tight-loose conflicts, often without anticipating them. They attract highly creative people who clash with the tighter structure and standardization that comes with running a larger organization. When I interviewed Ariel Cohen, who led an R&D enablement group for the start-up Mercury Interactive, which was later acquired by Hewlett-Packard in 2007 for $4.5 billion, he was quick to describe himself as a “serial start-up-er.” He prefers the high levels of looseness found in smaller ventures to the tight cultures of large corporations. “People at start-ups prefer to wake up, have an idea, then go execute this idea immediately,” he told me. “Then they test the idea as fast as possible in the marketplace, then change it or ditch it.” But when start-ups begin to scale up, greater hierarchy and rules are introduced, as Cohen observed firsthand. “After they acquired us, Hewlett-Packard hired new people who liked to plan and research their ideas first. But it slowed their creativity down to add more process,” he said. “For people like me, it was frustrating that I needed to persuade them to try new ideas. At the same time, they saw my approach as totally random and impulsive, like I had no due diligence.” This is tight-loose conflict in action. Soon after Mercury Interactive joined HP, Cohen left to go lead another start-up.

Even if they aren’t merging with another company, some organizations are in dire need of renegotiating their culture when they start to approach extreme ends of tightness or looseness. Take ride-sharing start-up Uber, which, in the years after its founding in 2009, became infamous for bulldozing through regional ordinances, using below-the-belt tactics against competitors, and hiding certain business practices from local regulators. The company’s normless ideology contributed to its immense success, but also to a major crisis. In 2017, a New York Times exposé unveiled Uber’s recklessly loose, “anything goes” work culture. Several former employees described the exceedingly loose work environment as a “frat house,” rife with unprofessional and even abusive behavior. Following the company’s sexual harassment scandal, Uber CEO Travis Kalanick was forced to resign. It later came out that higher-ups had also hidden from the public a major hacking. In an already freewheeling tech industry, where creativity is sometimes prized above all, Uber took its looseness to an extreme, leaving shareholders and new management to impose order.

Just as Uber came under intense scrutiny, another company faced its own public relations debacle. In 2017, a horrific incident played out on one of United Airlines’ commercial flights, all of it documented on video. With the flight overbooked, airline personnel asked passengers to give up their seats in exchange for an eight-hundred-dollar voucher. Without any volunteers taking the deal, the United computer system designated that four passengers had to be rebooked on another flight. Of these selected passengers, one person refused to forgo his seat. In response, the cabin crew, following company rules, called in airport security to escort the passenger off the plane. The security guard forcibly dragged the passenger, bleeding and screaming with pain, off the plane as nearby passengers captured the scene on their cell phones. The footage went viral and turned into a brand-damaging PR nightmare for United.

United’s tight culture may have been partly to blame. After the incident, United insiders told me that the company historically expected its employees to closely abide by its manuals and rules. In the airline industry, which must demonstrate safety and accountability every day, strong adherence to protocol is critical—but this expectation can be a double-edged sword. “United seems to have hired, or at least trained, employees who love rules more than common sense,” one veteran employee told me. Quite clearly, extremely tight cultures can inadvertently create an overcontrolled, static work environment in which employees are afraid to speak up and can have difficulty improvising in unexpected situations. Knowing this now, United is seeking to negotiate its tightness by setting up a support team to help triage customer issues that can arise. Based in Chicago, this new team assists staff on the ground with formulating creative solutions for these unexpected situations in order to avert future blunders.

Tightness-looseness in organizations is continuously renegotiated, contested, and sometimes totally altered, due to the ever-changing nature of customers, markets, stakeholders, and clients—not to mention bad PR. Some businesses, like United, may indeed operate best under tight conditions, but these companies’ leaders need to know when and how to give employees more latitude when the situation warrants it. At the same time, loose businesses, such as Uber, would benefit from knowing when and how to insert stronger norms into their daily practices.

Many companies today are striving to develop tight-loose ambidexterity. The importance of being “ambidextrous”—of balancing the need to explore new frontiers with honoring steadfast traditions—was first promoted by management scholars Charles O’Reilly and Michael Tushman in a 2004 Harvard Business Review article. Much like a person who can write fluidly with both her left and right hands, organizations need to learn to wield both tight and loose capabilities to operate effectively. A culturally ambidextrous company may favor tight over loose norms, even designating one as its dominant culture, while being capable of deploying the opposite set of norms when necessary.

When loose organizations insert some tight features into their daily operations, I call this structured looseness. Take Google’s adoption of the 70/20/10 rule, which guides employees on how to spend their time at work. The rule states that 70 percent of employees’ time should be focused on assignments from their managers, 20 percent on any new ideas that may be peripherally connected to their main projects, and the last 10 percent on any fun projects they want to initiate on their own terms. While clearly structured, the rule still allows workers to carve out space for personal creativity and flexibility.

The culture of another loose organization, the world-renowned animated-film studio Pixar, manifests as flexible work hours, hidden bars, and free pizza and cereal. “There was actually an individual here who took the ceiling out of his office, because he wanted the natural light,” the facility manager told SFGate journalist Peter Hartlaub during a tour in 2010. “It was a little extreme, but we don’t freak out about it.” To come up with innovative new film ideas, Pixar brings together incubation teams made up of employees from various backgrounds and skill sets. While these teams are left to their own devices, senior managers still monitor each team’s ability to work well together, particularly paying attention to whether they share a healthy social dynamic. Each incubator, moreover, has a producer and director who track the team project’s time constraints and budget. Thus, while Pixar is highly loose, its operations include enough structure and rules to keep things balanced.

On the flip side, steering a tight organizational culture into a looser state is what I refer to as flexible tightness. This happens when tight organizations allow employees to have more discretion. Toyota is a case in point. Toyota is a tight organization that relies on rules and standard operating procedures. But in recent years, it has begun to incorporate several practices to inspire creativity and improve customer service. It’s decentralizing its decision-making processes by allowing regional heads to have more discretion. Toyota’s leaders are also beginning to invite workers to experiment and innovate on their operational systems and products (a loose practice), by using a strict eight-step process (a tight framework). Senior leaders specify overall company objectives using vague terms so that employees can interpret these goals subjectively, which introduces unconventional thinking into the planning process.

Even the U.S. military injects some looseness into its otherwise tight culture with its practice of “Commander’s Intent.” Billed as a road map to success for every mission and operation, it lays out how the commander should accomplish the mission’s goals while also recognizing that “man plans, and God laughs.” Commander’s Intent recognizes that in any military operation, there are too many unknowns, moving parts, and sudden changes in the battlefield for soldiers and officers to rely on a single strategy. A critical aspect of the policy is the “Spectrum of Improvisation,” which encourages soldiers to rely on tried-and-true strategies but empowers them, when faced with an unexpected event, to adapt the original plan to the unit’s goals.

“Managing culture is a tightrope walk,” Adam Grant, professor and author of Originals, told me. “Create too many norms and rules, and you miss out on creativity and change. Create too few norms and rules, and you miss out on focus and alignment.” The key, according to Grant, “is to find a balance of tight and loose: have a few strong values that are widely shared and deeply held, but maintain flexibility around the best ways to put those values into practice.”

How can organizations become more ambidextrous, smoothly shifting their loose or tight culture into a state of structured looseness or flexible tightness? It’s not easy, no matter how minor the change. But armed with an understanding of tight-loose, companies can diagnose what workplace factors need to change—whether it is the people they recruit, the practices they promote, or the people leading—to get the best results.

Tech businesses in China’s booming start-up economy, for example, face the significant challenge of cultivating relatively loose workplace cultures that deviate from the country’s pervasive tight orientation. Influenced by the strong norms dictated by the Communist Party, organizations throughout China mimic its top-down and bureaucratic managerial systems. Tech start-ups, however, want to generate creativity by modeling the loose work cultures of Silicon Valley’s iconic companies. Baidu, known as “China’s Google,” founded in 2000, tries to shift into a loose gear by seeking out employees who think outside the box. “We want people who aren’t slavishly obedient, or are too much the product of a pedagogical system that places too much emphasis on rote learning,” explains Kaiser Kuo, a former spokesman for Baidu and the host of the podcast Sinica, about Chinese current affairs. Employees receive copies of a book called the Baidu Analects, whose title riffs on the Analects of Confucius, a collection of the great philosopher’s pithy sayings. “It’s anecdote after anecdote of these borderline insubordinate employees who stuck to their ideas in spite of pushback,” says Kuo, “and the enlightened manager who let them do it, and ultimately they triumph.” But alongside this ethos of organizational dissent, Baidu also emphasizes reliability —“delivering tasks to the next team or person only when they’ve been perfected,” explains Kuo, and trusting colleagues to be willing and able to help out when they’re needed. This combination of loose norms with high accountability has been the key to Baidu’s success.

No doubt, changing a workplace’s culture can be a trial-and-error process. A senior executive at one of the world’s largest manufacturers of office furniture relayed to me the bumpy road the firm took as it tried to loosen up operations. For years it had operated a tight ship, but surveys of salaried employees revealed that they felt the performance appraisal system was overwhelming—full of forms, quarterly evaluations, employee ratings, and explicitly defined objectives attached to stacks of instructional documents. Workers had difficulty meeting these countless expectations, which led to disengagement. In its first attempt at flexible tightness, the company’s human resources department adopted an entirely opposite system that gave employees complete freedom to decide how they were going to be evaluated. Such a loose model defied the company’s generally tight culture and made people feel too uncertain. “We realized we have to have some boundaries on this freedom, and return to a tighter culture, but gradually bring in a bit of looseness,” the senior executive told me. The company ultimately reintroduced work objectives and rewards systems, but provided flexible options by allowing employees to participate in customizing sub-goals. The new system gave employees more flexibility and agency while retaining the overall dominant tight culture that they preferred.

As companies work toward greater tight-loose ambidexterity, one thing is clear: During these shifts, it’s critical for organizational leaders to embrace the new initiatives.

Consider the launch of USAToday.com. In 1995, to keep in step with the news industry’s digital revolution, Tom Curley, then USA Today’s president and publisher, prepared to expand the company’s print media business online. He hired new leadership to create a department that, like the work cultures of other digital news companies, was much looser than traditional newsrooms. He communicated his vision to existing print-media leaders, some of whom voiced stiff opposition to investing in a fast-paced and arguably less rigorous online journalism division. Senior executives who didn’t buy into the new vision were swiftly removed or transferred. This created a “united front and consistent message” among the leadership, which Michael Tushman, coauthor of Lead and Disrupt, cites as critical for any organizational change.

Next, Curley worked toward promoting a collaborative spirit between the new digital division and the old-school print division to deal with fears on both sides. Those in print media feared that they’d lose their identity and value to the company and even become obsolete. They also worried that loose norms would bring disorganization, inefficiency, and loss of control. Members of the digital team, on the other hand, wanted free rein to let their creative juices flow and to avoid a confining structure. To mitigate these tensions and build collaborative bridges, Curley required the unit heads for web, print, and TV to attend daily editorial meetings to share ideas, choose the best stories to feature, and establish a cohesive strategy. He also created an incentive for cooperation—a bonus program that was contingent on all the media divisions hitting their goals. Ultimately, Curley struck an effective tight-loose balance, and the company became truly ambidextrous.

Quite clearly, there isn’t one best way to develop tight-loose ambidexterity within organizations. Some companies, such as USA Today, do this by cultivating mutual goals and respect across tight and loose units. Other companies channel more looseness directly into a tight group, or tightness into a loose group. Regardless of where and how they do it, the key elements involved are illustrated in Figure 7.2.

At a workshop I led at Harvard in 2016 with business leaders from across the globe, I shared the tightness-looseness framework and explained how it could manifest in organizational challenges. Many of them commented that they could now see the tensions cropping up in their organization with much greater clarity. Some returned to their offices to urge management to begin using the tight-loose language to help diagnose and solve problems. By understanding the hidden force of social norms in their organizations, business leaders can effectively shepherd their companies toward greater tight-loose balance.