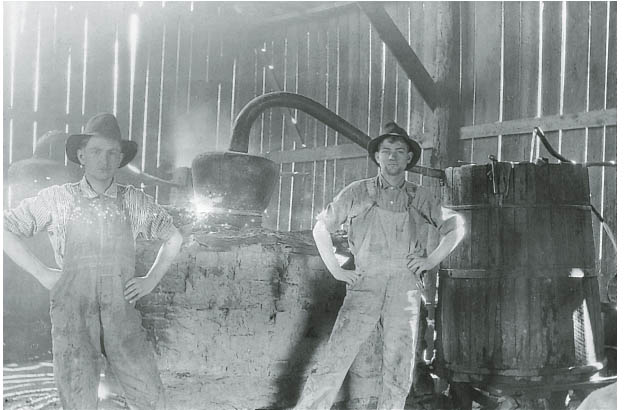

Pot stills at the Harlan Distillery in Monroe County, Kentucky, 1918. This photograph could have been taken in 1818, as the technology remained the same a century later. (Courtesy United Distillers Archive)

Spirits were distilled in America long before the birth of the whiskey industry. Rum and gin were produced in cities along the Eastern Seaboard by colonists who had brought their stills with them to the New World. Whiskey came into widespread favor only with the end of the Revolutionary War and the beginning of the westward expansion, when the costs of transporting the ingredients over the mountains made rum and gin too expensive to produce. Whiskey could, however, be made from readily available local produce, and it became one of the most common of the home-produced spirits. In the early years of the westward expansion, stills were still manufactured in the East, and settlers had to bring them west with them. But demand soon grew large enough that coppersmiths began to manufacture them in western Pennsylvania and Kentucky.

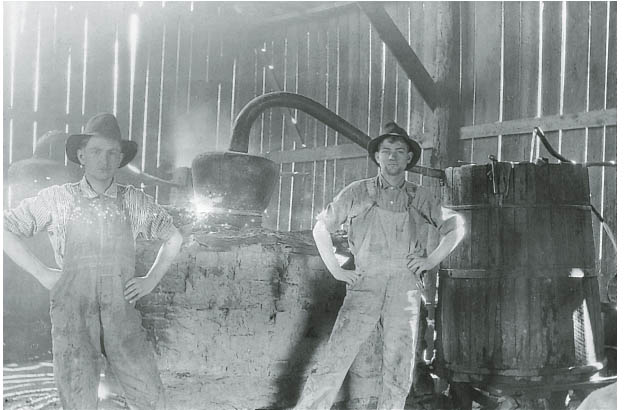

The American pot still differed little from the European still, which had been in use for centuries. It was simply a large copper pot made to be fitted with a separate head and gooseneck that could be attached to the copper worm, a coil of copper tubing immersed in a barrel of water. The fermented mash, or “distiller’s beer,” which was made from grain, was poured into the pot, and the head was positioned on top of the pot and sealed to prevent the vapors from leaking through the joint. The beer was heated over an open fire, allowing the alcohol to vaporize and pass through the worm, where the water cooled the vapors, which became liquid again, allowing the alcohol to be collected and stored in a cistern. The whiskey could then be refined and made more palatable by distilling it a second time—in either the same still or a second still called a doubler—refining the quality of the spirit by taking out unpleasant flavors. The end result was clear, unflavored liquid alcohol. Color and taste came from the fruit, sugar, or herbs added after distillation.

The Worm

The “worm” of an early pot still is a copper tube coming off the head of the still that is coiled through a barrel of water to help cool and condense the vapors coming off the still. The invention of the worm is often credited to the Germans. It is this innovation that makes the production of spirits practical. The worm cools the alcohol vapors, causing them to condense into liquid form.

Because the stills most of these farmers possessed needed to be easy to transport, they were rarely over 150 gallons in capacity. Their output was therefore limited—never more than 1,000 gallons a year and sometimes less than 100. The still described by Henry Clay in an undated copy of a court document filed in Kentucky’s Fayette County Court on behalf of his cousin Green Clay—Green Clay had in October 1800 purchased a still from George Coons and John Cock that had never been delivered—is typical. It is described as follows: “one still to hold one hundred and fifteen gallons exclusive of the cap, and has a cap and worm with the still.” This is an average size for a still. It is large enough that beer from two fifty-gallon fermenting tubs can be distilled in it. Clay goes on to indicate that the still “should be of good thick copper, such as was common for a still of that size and to be finished off in a good workmanlike manner, with lead where the arm joins the cap and the spout.”1 Such construction would guarantee many years of use.

Pot stills at the Harlan Distillery in Monroe County, Kentucky, 1918. This photograph could have been taken in 1818, as the technology remained the same a century later. (Courtesy United Distillers Archive)

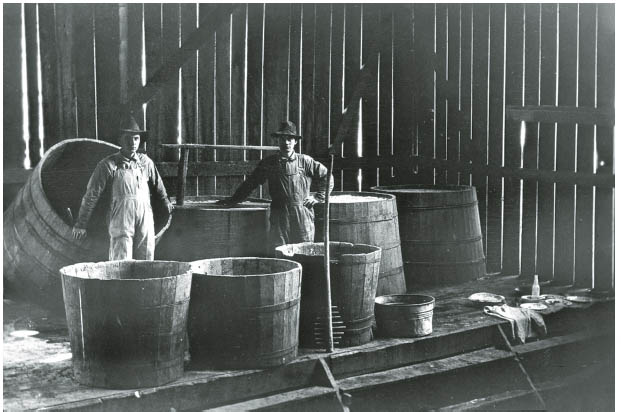

Farmers in the newly opened territories looked at distilled alcohol the same way they looked at salted pork and smoked hams—as just another product to sell, whether in jugs or barrels, for cash or barter for needed goods and services. A farm-based distillery was usually a small-time operation, typically one or two stills with a capacity of about one hundred gallons each. The beer a farmer distilled was made from grain he raised. Farmers who did not own stills often used a neighbor’s, paying for use with a portion of the whiskey produced. Millers too distilled whiskey. Because they kept a portion of the grain they milled as payment, they always had a surplus on hand that could be turned to profit. And many millers turned this surplus grain into whiskey, which was more valuable than grain because it was easier to transport.

Early distillers made their whiskey from whatever grain they had on hand—usually corn or rye but also occasionally wheat. An example of an early recipe (ca. 1800) for mash bill (the ingredients from which the fermented mash is distilled) is the “Pennington Method”:

Take 12 gallons of boiling water Put into a tub then put in one 1 bus’l corn meal and steer well go over three tubs in this manner Then begin at the first tub & put into it 10 or 12 gallons of boiling water in each then stir as above Then fill your still again with water to boil—20 minutes after this put 4 gallons cold water to each tub then add one gallon of malt add to this half bus’l rye meal stir these all together well when the still boils add ten gallons boiling water to each tub Stir as aforsaid, Then let your tubs stand ab’t 3 or 4 hours after which fill up your tubs with cold water Stir as above then let the Tubs stand until as warm as milk or rather cooler then yeast them.2

This is typical of recipes for mash bill that have survived from the late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth. Early distillers made either “sweet mash” or “sour mash” whiskey. Making a sweet mash involved simply cooking the grain and adding yeast to make the beer. The Pennington Method is an example of a sweet mash. A sour mash was made by using some of the liquid from a previous distillation in the new mash. This process ensured consistency between batches by creating an environment favorable to the particular yeast strain flavoring the whiskey. It also made that mash more acidic, preventing bacterial infection.

One of the earliest surviving recipes for sour mash dates to 1818 and is attributed to one Catherine Carpenter of Casey County, Kentucky, who continued to run her husband’s distillery after his death. She recorded her recipes for both sweet mash and sour mash:

The Harlan Distillery mash tubs, 1918. (Courtesy United Distillers Archive)

Wort or Mash?

Scotch whiskey is distilled from a “wort,” while bourbon whiskey is distilled from a “mash.” A wort is made by cooking the grains and draining the sugary liquid off before fermentation, leaving the solids behind. A mash leaves the grain meal in the liquid during the fermenting process. Since pot stills have to be cleaned between every distillation, the fewer solids involved in distillation, the better. Grain solids will harden in the still, making it more difficult to clean. Modern bourbon is made with a continuous still, and mash flows through the column without interruption, washing the solids to the bottom of the still, where they become part of the spent beer.

To a hundred gallon tub put in a bushel and a half of hot water then a half a bushel of meal Stir it well then one bushel of water; then a half bushel of meal & amp; so no untill you have mashed one bushel and a half of corn meal—Stir it all effectively then sprinkle a double handful of meal over the mash let it stand two hours then pour over the mash 2 gallons of warm water put in a half gallon of malt stir that well into the mash then stir in a half a bushel of Rye or wheat meal. Stir it well for 15 minutes put in another half gallon of malt. Stir it well and very frequently untill you can bear your hand in the mash up to your wrist then put in three bushels of cold slop or one gallon of good yeast then fill up with cold water. If you use yeast put in the cold water first and then the yeast. If you have neither yeast or Slop put in three peck of Beer from the bottom of a tub.

Put into the mash tub Six busheles of very hot slop then put in one Bushel of corn meal ground pretty course Stir well then sprinkle a little meal over the mash let it stand 5 days that is 3 full days betwist the Day you mash and the day you cool off—on the fifth day put in 3 gallons of warm water then put in one gallon of rye meal and one gallon of malt work it well into the malt and stir for 3 quarters of an hour then fill the tub half full of Luke warm water. Stir it well and with a fine sieve or otherwise Break all the lumps fine then let stand for three hours then fill up the tub with luke warm water.

For warm weather—five bushels of slop instead of six let it stand an hour and a half

Instead of three hours and cold water instead of warm.3

Because the quality of the whiskey they produced was inconsistent, farmers used other methods to improve its taste, such as flavoring it with fruit to make cordials or herbs to make gin. There are many recipes from early nineteenth-century Kentucky for making blackberry cordial or cherry “bounce” from whiskey. Cherry bounce—a form of flavored whiskey made from local ingredients—was a popular spirit in early Kentucky. It was intended both for personal use and for sale to others. The Beall-Booth Family Papers of the Filson Historical Society offer these recipes from the first decade of the nineteenth century:

Cordials—To one gallon of finished whiskey add two quarts of clear water. Then add about 30 Drops of the oil of cloves and five or six drops of the oil of Aniss Seed in a sufficient quantity of Sirup to sweeten it—Gin may be made by adding about 25 drops of the oil of juniper to each gallon.

Receipt to make Cherry Bounce of finished whiskey. Take the bark of the root of the wild cherry tree and steep it in hot water till it becomes strong then add such proportions of it as is sufficient to give it the cherry taste. Take care to have it high colored and sweetened with sirup.

Another method of finishing whiskey for consumption was to filter it through charcoal. The charcoal would remove many of the unpleasant-tasting fusel oils (nonethanol alcohols produced by the yeast as well as nonalcohol flavors in the spirits) that were left after distillation. It would also neutralize some of the natural acids in the alcohol, making it sweeter. The Beall-Booth Family Papers also give us a description of charcoal filtering:

Receipt to purify whisky and other Ardent Spirits. Take a tub of one hundred gallons and put a false Bottom about 8 or 10 inches from the other bottom the false bottom must be full of Holes then fasten on the top of the false bottom three or four thicknesses of white flannel then put about three or four inches thick clean white sand then put about 18 or 20 Inches thick of pulverized charcoal made of good green wood such as sugar tree Hickory & then fill up the vacancy with whisky or other ardent spirits take care to pour it up til it becomes perfectly clear and purified. To make Rum add one to five [i.e. one to five runs through the filter] Brandy one to four or five.

This process is similar to the “Lincoln County Process” used by Jack Daniel’s Distillery and George Dickel’s Cascade Hollow Distillery to make their Tennessee whiskey. The main difference is that, in the modern Tennessee whiskey distillery, the tub is taller and holds more charcoal, allowing the distiller to run the whiskey through fewer times.

At about the same time that whiskey came into favor with distillers, taxes came into favor with legislators. The requisite two-thirds of the original thirteen colonies had ratified the Constitution of the new United States by the summer of 1788, clearing the way for the creation of the new federal government. The most important thing distinguishing this new government from the much weaker one created by the Articles of Confederation was its ability to levy taxes nationwide. Because the new government had assumed the debts incurred by the pursuance of the Revolutionary War and the operation of the Confederation government, it needed money. To raise it, it established a number of taxes and tariffs, including an excise tax on whiskey and other distilled spirits in 1791.

The whiskey tax was promoted by the secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, and his supporters. The designers of the tax wanted to move the economy away from cottage industries and into an industrialized economy. In theory the tax was fair to all producers, but in reality it favored the larger producers along the Atlantic coast. For one thing, it was to be paid in hard currency, and there was a shortage of coinage of any type in the frontier West. In the largely barter economy that prevailed there, whiskey itself became a substitute currency, and farmers traded it for supplies and even land. The larger distilleries in the coastal cities had greater access to currency since they most often sold their product for cash.

The government’s dual standard for tax collection also favored the big distilleries. In urban areas, a tax collector could monitor production and tax the amount of the spirit actually produced. Those distillers who lived in areas that “the law defined as the country,” as William Hogeland put it in his history of the Whiskey Rebellion, were treated differently.4 The capacity of their stills was gauged, full-time production was assumed, and a tax equivalent to four months’ production was assessed. Because farmers rarely distilled more than two months a year and sometimes as little as one week a year, they were being charged taxes for whiskey they would never produce.

Efforts to collect the whiskey tax in the frontier West met with resistance. Some tax collectors even found themselves tarred and feathered. In September 1792, President Washington issued a proclamation urging the people to obey the law. Nevertheless, the protest widened as people who worked hard for what little they had saw the law as oppressive. The federal government was aware of the continuing resistance but, for the moment, tried to settle the matter in the courts. And in some cases successful compromises were reached. For example, the collector of the federal tax in Kentucky was very sympathetic to the concerns of the distillers, as was the federal judge appointed to the state, and cases brought before his court usually resulted in taxes being collected only on the amount of whiskey actually produced, with generous terms of payment also being offered.

Whisky or Whiskey?

The traditional distinction is that whiskey is used for spirits from rebellious former British colonies and whisky for spirits from loyal former British colonies. Thus, Scotch and Canadian products are considered whisky, and Irish and American products are considered whiskey. The fact of the matter, however, is that spelling depends on brand. George Dickel uses whisky, while Jack Daniel’s uses whiskey. Even within the same company there can be variation. Brown-Forman uses whisky for Old Forester and whiskey for Early Times.

Although the Whiskey Rebellion was initially centered in western Pennsylvania, resistance to the tax spread throughout the frontier counties of Appalachia. In the spring of 1794, arrest warrants for people who refused to pay the tax began to be issued, armed militiamen joined the cause, and the protests turned violent.

Hamilton was not necessarily displeased with this turn of events. He and his supporters saw it as an opportunity to show the nation that the new federal government could and would enforce its laws, using force if necessary. Hamilton urged President Washington to raise an army and send it into western Pennsylvania to restore order. In August 1794, Washington issued another proclamation ordering the insurgents to disperse and also asked the governors of Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia to provide fifteen thousand troops from their militias. He also sent three negotiators to western Pennsylvania to meet with David Bradford, the de facto leader of the insurgency, to attempt to find a peaceful resolution to the crisis. The negotiations failed, and the federal army left its encampment at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, on October 14 with Virginia governor Henry Lee at its head. Bradford and many of his supporters fled to Spanish Louisiana before the army arrived. The rest of the insurgents offered no resistance and were offered a chance to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. Many of those who refused were arrested, but only two people, Philip Wigle and John Mitchell, were actually convicted of treason. They were both pardoned by President Washington because he considered Mitchell to be a “simpleton” and Wigle “insane.” The lack of prosecutions caused Thomas Jefferson to question Hamilton’s motives in the whole affair, saying: “An insurrection was announced and proclaimed and armed against, but could never be found.”5 He would make the repeal of the whiskey tax part of his 1800 presidential campaign platform. After his election, he kept his promise by balancing the federal budget and, in 1802, repealing the whiskey tax, which was reimposed only when the government needed the money to pay for the War of 1812 and then the Civil War.

One of the legends to come out of the Whiskey Rebellion was that the Kentucky distilling industry was created by those rebels fleeing Pennsylvania ahead of the federal troops. This was not the case. The distilling industry had been well established in Kentucky long before the rebellion. And the rebels, as we have seen, fled south, not west.

The whiskey tax did not do what Alexander Hamilton had hoped—force the development of larger distilleries with improved production capacities. Farm distilleries remained small-time business operations for many decades to come. Ironically, it is the licenses acquired during the whiskey tax days that give us our best view of these operations. Licenses indicate the number of stills involved, the capacity of each, the length of time distilling was authorized, and the licensee (not necessarily the owner). The license for a still owned by Daniel Weller, a farmer distiller and the grandfather of the distiller and rectifier William LaRue Weller, is a typical example. It indicates that Weller’s neighbor, Jacob Hirsh, is authorized to use Weller’s ninety-gallon still for the two weeks between September 18 and October 2, 1800.6 Hirsh was therefore responsible for the taxes on the whiskey produced during that time period—probably about one hundred gallons.

Attempts were made to establish larger distilleries early in the nineteenth century. In 1816, for example, a group of investors from New England raised $100,000 and came to Louisville to build a modern distillery. They hoped that, by using European methods, they would produce a superior whiskey. The Hope Distillery, built in west Louisville at the foot of Sixteenth Street, housed two huge copper pot stills made from a reported ten tons of copper and had the capacity to produce twelve hundred gallons of whiskey per day.7 Like European distilleries, the Hope distilled its whiskey from a wort instead of a mash. A wort is made by cooking the grains into a sugary soup and removing the grain solids before fermenting the beer. A mash is fermented with the grain solids. Because the distillers were working with a wort, the corn was ground with the cob, the extra fiber working as a filter when the wort was drained from the mash. The idea was that distilling from a wort would prevent the grain from being scorched in the still and giving the whiskey a burned flavor, as was often the case with the whiskey made by the farmer distillers. But such large-scale production and such a high distillation proof also eliminated much of the grain flavor found in the farmer distiller–produced whiskey. The people of Kentucky still favored the whiskey produced in small pot stills, and the Hope Distillery failed by 1820. It would be several more decades before large-scale distilling would return to Louisville. In the meantime, the farmer distillers began making a new type of whiskey that they called bourbon.

Hope Distillery Grounds Becoming the Site of Louisville’s First Horse Racetrack

The Hope Distillery was located at the foot of Sixteenth Street in West Louisville along the Ohio River. It closed only a few years after it opened in 1817, and the hundred-acre site was abandoned. In 1827, the Louisville Jockey Club announced that it would “commence the first Wednesday in October, 1827, on the Louisville turf, Hope Distillery, and continue four days. First day, three-mile heats, $120; second day, two-mile heats, $80; third day, one-mile heats, $50; fourth day, three best in five, one mile and repeat” (J. Stoddard Johnston, Memorial History of Louisville from the First Settlement to the Year 1896 [New York: American Biographical Publishing Co., 1897], 323). The distillery site had become a horse racetrack.