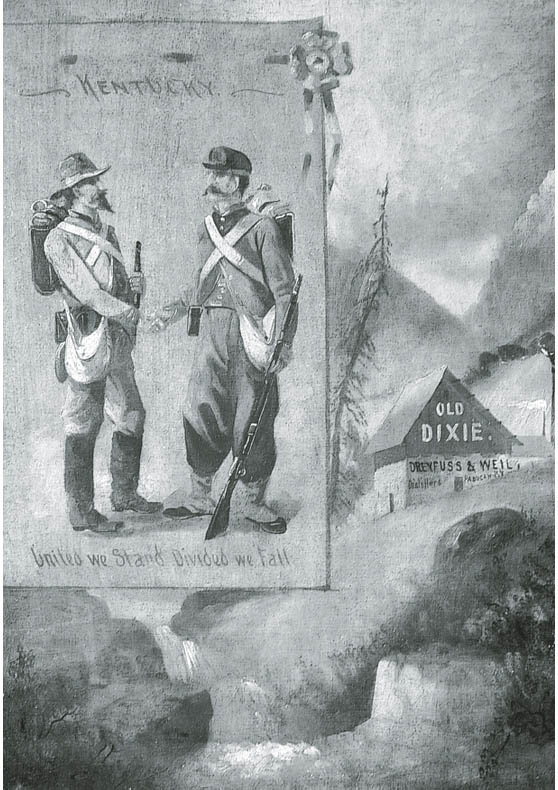

Old Dixie advertising painting, ca. 1895. (Courtesy Filson Historical Society)

As the reputation of Kentucky bourbon grew, so did the number of people who wanted to take advantage of that reputation by marketing a cheap imitation. These people were wholesale merchants—also known as rectifiers—who would purchase cheap whiskey, “rectify” (i.e., purify and/or flavor) it, and then resell it. (Louisville’s Whiskey Row was, during the first half of the nineteenth century, populated mostly by such wholesale merchants.) Initially, the rectifiers were supplied by farmer distillers with unaged white spirits of various proofs that had to be redistilled and filtered through charcoal to remove unwanted flavors and reflavored by aging in charred barrels. As the century progressed, the invention of the column still gave them an added source of whiskey that was both cheap and distilled to a very high proof, making it neutral in taste. Flavoring and coloring methods were also developed that allowed them to bypass the aging process. They rarely came close to matching the taste of a true bourbon, but the end result was cheap and sweet and, thus, easy to market. It also took only hours, and not four years, to produce.

Rectifiers’ Flavoring and Coloring Agents

Rectifiers used many different products to make their whiskey. “Burnt sugar” is brown sugar used to sweeten and color the alcohol. Prune juice and cherry juice were also used to color and flavor the alcohol. Some of the more unusual products include creosote and cochineal. Creosote is the oily product used to preserve the wood of utility poles. Cochineal is a red dye made from the crushed, dried bodies of the female cochineal insect (Dactylopius coccus), which lives on cacti of Central America and Mexico.

Not surprisingly, recipes for these imitation products were in great demand. One example of the books that began to appear on the market in response is Pierre Lacour’s ca. 1860 The Manufacture of Liquors, Wines and Cordials without the Aid of Distillation. Lacour gives recipes for rectified or imitation Irish, Scotch, and American styles of whiskey as well as many different styles of brandy and cordials. These products all use neutral spirits as a primary ingredient, and most do not use any aged whiskey at all. Examples of Lacour’s recipes for whiskey include the following:

Irish Whiskey: Neutral spirits, four gallons; refined sugar, three pounds, in water, four quarts; creosote, four drops; color with four ounces burnt sugar.

Scotch Whiskey: Neutral spirits, four gallons; alcoholic solution of starch, one gallon; creosote, five drops; cochineal tincture, four wine glasses full; burnt sugar coloring, quarter of a pint.

Oronoko Rye Whiskey: Neutral Spirit, four gallons; refined sugar, three and a half pounds; water, to dissolve, three pints; decoction of tea, one pint; burnt sugar, four ounces, oil of pear, half an ounce; dissolved in an ounce of alcohol.

Tuscaloosa Whiskey: Neutral spirits, four pints; honey, three pints; dissolved in water, four pints; solution of starch, five pints; oil of wintergreen, four drops, dissolved in half an ounce of acetic ether; color with four ounces burnt sugar.

Old Bourbon Whiskey: Neutral spirits, four gallons; refined sugar, three pounds, dissolved in water, three quarts; decoction of tea, one pint; three drops of oil of wintergreen, dissolved in one ounce of alcohol; color with tincture of cochineal, two ounces; burnt sugar, three ounces.

Monongahela Whiskey: Neutral spirit, four gallons; honey, three pints, dissolved in water, one gallon; rum, half gallon; nitric ether, half an ounce. This is to be colored to suit fancy. Some customers prefer this whiskey transparent, while others like it just perceptibly tinged with brown; while others, again, want it rather deep, and partaking of red.1

These recipes are valuable for two reasons. First and foremost, they offer direct evidence of the way in which cheap whiskey was being produced. But they also offer indirect evidence about the products that were being imitated. For example, in 1853, when The Manufacture of Liquors was published, Monongahela whiskey was not always aged. We know this because the recipe for Lacour’s version indicates that the color should depend on customer preference and that unaged/uncolored, slightly aged/lightly colored, and more extensively aged/deeply colored versions were all available on the market. Bourbon, on the other hand, should always have a deep red color (imparted by cochineal) and tannic and minty flavors (imparted by tea and wintergreen, respectively). American whiskeys were evidently sweet—sugar is Lacour’s prime ingredient—with Monongahela and Tuscaloosa whiskeys in particular being known for their strong honey flavor. Scotch whiskey should be deeply colored but not sweet (the only flavoring ingredients are starch and creosote). Irish whiskey seems to have been midway between Scotch and American whiskeys since the recipe calls for some sugar but also for some creosote.

The nineteenth century was not all smooth sailing for the distilling industry. The Civil War proved a disruption to business. This was especially true in the South, where spirits were prohibited (they could be used only by the Confederate army for medicinal purposes) and copper stills were confiscated and melted down for the manufacture of war materiel. The main effects in the North were the imposition of a federal tax on the production of distilled spirits to pay for the war2 and the creation of a lawless atmosphere in some border states, especially Kentucky and Tennessee. (Charles D. Weller and McWiley Parker of the Louisville whiskey firm W. L. Weller and Bro. were robbed and murdered by two gunmen in Clarksville, Tennessee, in July 1862 while traveling on business.)3 Still, the demand for whiskey remained strong in both the Union and the Confederacy, and Kentucky distilleries were more than ready to fulfill it.

The strength of the Kentucky distilling industry is evident in the listings under whiskey in the 1864–1865 edition of Edwards’s annual directory for the city of Louisville:

Anthony Jacobs & Co. 133 4th between Main and Water. Bartlett, V. R. & Sons 62 Main between 6th & 7th. Billing and Druesbach 310 Main between 3rd & 4th. Block, H. & Co. 833 Main between 8th & 9th. Boes, John & Co. 119 Market between 1st & 2nd. Clark, James A. & Co. 219 3rd between Main and Market. Clarke, Samuel S. 119 Market between 1st & 2nd. Clary, Francis Main between 11th & 12th. Cochran, John & Son 330 Main between 3rd & 4th. Cowan, D. H. 724 Main between 7th & 8th. Cropper, Patton & Co. 143 & 145 4th between Main and Water. Crump, Ropert H. 208 Main. Dorn, Barkhouse & Co. 428 Main between Bullitt and 5th. Finck, C. Henry 310 Market between 3rd & 4th. Gaetano, V. D. & Co. 700 Main between 7th & 8th. Gheens, John R. & Bro. 308 Main between 3rd & 4th. Koch & Leonhard 201 Market between 2nd & 3rd. Lanham, James T. 3rd between Market and Jefferson. Laval, Jacob 120 & 122 2nd between Main and Water. Lichten, A. & Bro. 219 5th between Main and Market. McDermott, James & Co. 716 Main between 7th & 8th. Monks, J. & Co. 732 Main between 7th & 8th. Moore, Bremaker & Co. 722 Main between 7th & 8th. Nuttall, R. & Sons 236 Market between 2nd & 3rd. Ratel, William 135 4th between Main and Water. Schaeffer, F. J. Market between 6th & 7th. Schrodt & Woebler 5th between Main and Water. Schroeder, J. H. & Sons 28 Wall. Shrader, R. A. & Co. 210 E. Market above Brook. Smith, A. T. & R. L. 2nd between Main and Water. Somerville, C. H. 620 Market between 6th and 7th. Stege, Reiling & Co. 232 Market between 2nd & 3rd. Taylor, E. H. Main se corner 7th. Terfloth, John C. & Co. 138 4th near Main. Thierman, H. & Co. 614 Market between 6th and 7th. Thompson & Co. 79 4th between Main and Market. Vissing, Herman Jefferson between Jackson and Hancock. Walker, W. H. & Co. 206 Main. Welby, George 336 Main between 3rd and 4th. Weller & Buckner 612 Main between 6th and 7th. Wolf, Charles and Co. Main between 11th and 12th. Zahone, A. & Sons 145 5th between Main and Water.4

No companies on this list survive today, but there are a few familiar names. We find, for instance, William LaRue Weller, who partnered with a man named Buckner after his brother Charles was murdered. And we also find E. H. Taylor, whom we met in the previous chapter.

Taylor is an important figure in the postwar distilling industry in that he was one of the earliest to grasp the concept of marketing and was very skilled at promoting his products and creating brand recognition. One of his first efforts at promotion involved Old Crow after Gaines, Berry and Company had assumed production. It came to his attention that, while a guest at the home of General Benjamin Butler in Washington, DC, Judge George Washington Woodward of Pennsylvania was bragging about the quality of a twenty-year-old rye whiskey from Pennsylvania, claiming that it was as good as any Kentucky bourbon. William Brown of Kentucky, who was present at the time, took up the challenge and wrote to the firm Paris and Allen, the distributor of Old Crow in New York City, asking for a bourbon aged at least fifteen years so that it could be compared to Woodward’s preferred brand. Paris and Allen in turn contacted Taylor, who sent Brown a bottle of twenty-year-old Old Crow to represent Kentucky bourbon in the ensuing contest of honor. After the contest, Taylor issued the following press release:

E. H. Taylor Jr.

Edmund Haynes Taylor was born at Columbus, Kentucky, in the Jackson Purchase region of western Kentucky in 1830. His grandfather, Richard Taylor Jr., was the surveyor for the state, and his father, John Taylor, traded merchandise and slaves between Kentucky and New Orleans. Edmund was only five years old when his father died of disease—probably typhus—while returning to Kentucky from New Orleans. Edmund lived with his great-uncle Zachary Taylor for a while before going to Lexington to live with his Uncle Edmund Haynes Taylor, who saw to it that he was well educated. It in this period that he added the Jr. to his name.

Thanks to his uncle’s connections, E. H. Taylor Jr. entered the banking business in 1854 as a partner in the firm Taylor, Turner and Co. This firm became Taylor, Shelby and Co. in the year 1855, and it catered to many of the important people in Lexington, from Cassius Clay to John Hunt Morgan. The bank failed in the financial troubles of 1857, and Taylor went into the commodities business. During his travels with the bank and as a commodities trader, he saw a Lincoln-Douglas debate and stayed at a boarding house in Missouri with William Tecumseh Sherman. During the Civil War, he traded in cotton after using his connections with John J. Crittenden to secure permission to acquire cotton in Memphis, Tennessee. He also entered into the liquor trade with an office on Whiskey Row in Louisville in 1864.

Taylor toured European distilleries in 1866, learning the latest in distilling technology and technique. He returned to the United States and applied this knowledge to the design of the Hermitage Distillery. In 1869, he purchased the Swigert Distillery, on the banks of the Kentucky River in Leestown. He rebuilt it—renaming it the OFC (or Old-Fashioned Copper) Distillery—using the knowledge he gained in Europe. He was determined to make it not only a great distillery but also an attractive distillery that could be shown with pride to potential customers. He paid attention to the small details. This was a pot still distillery that made “old-fashioned copper” bourbon in the tradition of James C. Crow. The buildings were of brick and steel with modern “patent” warehouses with barrel ricks and steam heat. Taylor also paid attention to the package the bourbon he sold came in—the barrel. He insisted on brass rings for the barrels and made sure they were all clean and bright before being shipped to a customer. He promoted his whiskey by publicizing letters of recommendation from important customers, prints of the distillery for display, and all the other advertising paraphernalia offered at the time. He was his own marketing department and advertising agency before most people had ever heard of such things.

Taylor would fall victim to bad financial times and an overproduction of whiskey, losing control of the distillery in 1878 to the firm Gregory and Stagg from St. Louis. He eventually created the bourbon brand Old Taylor and rebuilt another distillery to make it. He championed the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. He became the mayor of Frankfort and a leader in the movement that kept the capital in Frankfort when the state decided it needed a larger statehouse to house the government.

When Prohibition took effect in 1920, Taylor tried to fight it in the courts but failed. He was out of the whiskey business. In his forced retirement, he concentrated on breeding Hereford cattle. He died in Frankfort on January 19, 1923, just weeks short of his eighty-third birthday.

Important decision at Washington!! Kentucky vs. Pennsylvania. Old Bourbon vs. Old Rye. A decision has just been rendered at Washington which cannot fail to be of particular interest to our readers. We give a sketch of the case as related to us. “An evening not long since at Genl. Butler’s residence in Washington, Judge Woodward of Pennsylvania remarked that he knew of some Rye Whiskey over 20 years old that was made in his state which would excel any Bourbon ever distilled. The gauntlet thus thrown down was instantly accepted by the Hon. Wm. Brown of Kentucky. He wrote at once to Mssrs. W. A. Gaines & Co., Frankfort, Ky.—(owners of the celebrated Hermitage Distillery) for a bottle of the finest ‘Bourbon’ Kentucky could produce, while Judge Woodward procured a bottle of the ‘Rye.’ Mssrs. Gaines & Co. after a careful comparison selected a bottle of the renowned ‘Old Crow’ (of which they are also proprietors) made by the old Scotchman himself 21 years ago. As both samples were over 21 years of age, they were fully mature, and though not able to vote were fitting representatives of their respective States. The Court being duly convened with that eminent connoisseur, Genl. Butler as presiding judge, the case was called. Both sides being ready, counsel at once proceeded upon the merits and while ably argued, the samples themselves were more spiritually eloquent. After the evidence was all in and well digested, the judgement was rendered in favor of Kentucky’s ‘Old Crow’ as being the most mellow, rich, full yet delicately flavored and surpassing in boquet.” We congratulate Mssrs. W. A. Gaines & Co. on their success, which they richly deserve, as they have devoted years of study to the perfection of distillation and spared no expense in pursuit of purity and quality. The “Hermitage” Distillery, of which Frankfort is justly proud, is a result of their labors, and its product though not two years old has an unequaled reputation both at home and abroad.5

What Taylor was doing was “branding” Old Crow. That is, he was bringing it to national attention in a context that reinforced the quality and, presumably, the reliability of his product and, thus, creating a demand for it among consumers who until that point preferred familiar, locally produced whiskey. He was also piggybacking on the reputation of the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, the original maker of Old Crow, to brand the newly formed Gaines, Berry and Company. He would similarly market his own future distilling ventures.

Taylor was not alone in grasping the importance of branding. Others followed his lead, giving birth to a marketing revolution that swept the distilling industry. Equally important to the marketing revolution were Hiram Walker and the Brown brothers.

Hiram Walker was born in the United States but built a distillery in Ontario, Canada, in 1858 and started producing what he called Walker’s Club whiskey. He decided not to sell his whiskey until it was properly aged and then, to ensure quality, to sell it only by the bottle. Walker’s Club became very popular when it was released to the market in the 1860s, and soon there were hundreds of whiskeys calling themselves club whiskeys. In 1873, Congress passed legislation requiring that the country of origin be stated on all imported whiskeys, and Walker’s Club became Canadian Club.

The success of Canadian Club caused Hiram Walker to spend a lot of time in court defending his brand from imitators and frauds. It was apparent that the industry needed a way to register brand names, and soon the companies were publishing claims to their brands in the major trade magazines such as Mida’s Criteria in Chicago and Bonfort’s Wine and Spirits in New York. These claims were later used as proof of ownership when the U.S. government passed its first trademark registration rules in 1881. The industry continued to publish trademarks in the trade magazines up until Prohibition.

In the United States, George Garvin Brown and his brother J. T. S. Brown Jr. created a whiskey firm and, with it, the brand Old Forester in the year 1870. The firm would change names several times before the end of the century, eventually becoming Brown-Forman (as it is known today), but George Garvin Brown stayed on as its head, and Old Forester remained his main brand of bourbon whiskey. Like Walker, the Browns too decided to sell their whiskey only by the bottle. Their rationale was somewhat different, however. Whiskey was a popular medicine at the time, but physicians resisted prescribing it because it was sold mostly by the barrel and quality could vary greatly from barrel to barrel. Old Forester was the first bourbon to be available exclusively in bottles—sealed bottles that assured a greater level of quality assurance. The Browns named their whiskey for the Louisville physician William Forrester (the second r was dropped from the name after Forrester retired). They then designed a label that looks very much like a physician’s prescription and includes a handwritten claim to quality: “Nothing Better in the Market.”

As brand names grew, so did their marketing ventures. Advertisements (by now in color) in newspapers and magazines were employed to make brand names known to consumers. Jugs and decanters, glassware and swizzle sticks, emblazoned with the brand name were manufactured and sold to consumers very cheaply. Similarly adorned mirrors and artwork could be purchased from the distilleries for display in bars and saloons. Booklets describing distilleries and brands were published. The marketing revolution was in full swing.

The distillers and rectifiers quickly learned that, the more they promoted their brand, the more they sold. But they also learned that they had to be on their guard against trademark infringement and counterfeiting. One distiller, James E. Pepper, attempted to thwart counterfeiters by affixing strip stamps carrying his signature across the corks in his bottles of whiskey. His advertisements warned consumers to buy only bottles with intact stamps. Otherwise, they may not be buying “Genuine Pepper” whiskey. The concept of the strip stamp over the cork would later be taken up by the government in the form of tax stamps.

By the end of the nineteenth century Kentucky’s whiskey industry had earned a national reputation for producing a quality product. This product was well advertised and was available in all states of the Union as well as markets abroad. With this success came increased profits—and greater incentive to imitate the product. This state of affairs would divide the industry and create the need for legislation laying out guidelines for what could be considered whiskey.