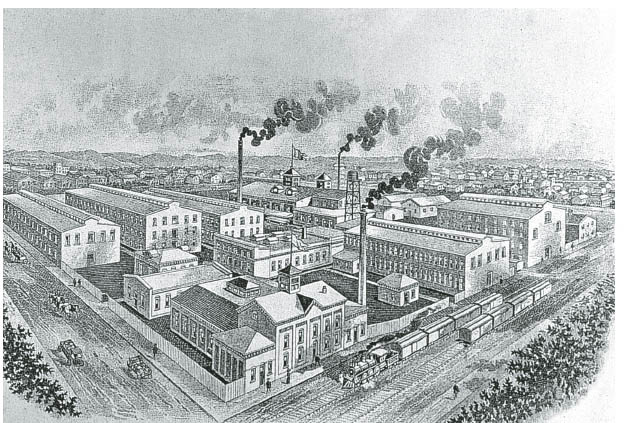

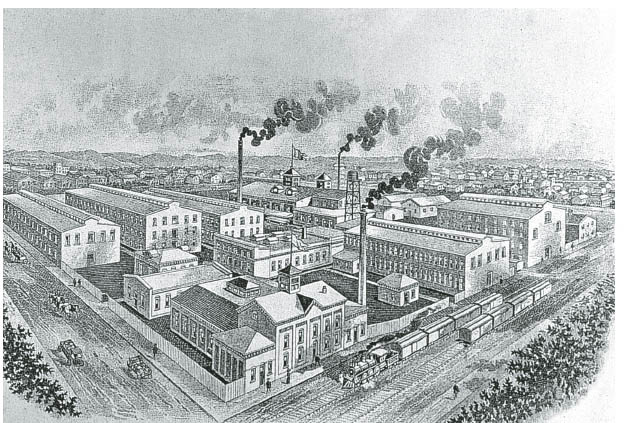

Belmont and Astor Distilleries in Louisville, Kentucky, with their bonded warehouses, ca. 1890. (Courtesy United Distillers Archive)

The distilling industry in the United States had, since its inception, been free of government regulation. And, until the 1860s, the federal government had, as we have seen, imposed taxes on the distilling industry for only two brief periods—1791–1802 and 1814–1817—both times to pay off the debts it had incurred waging war against Great Britain. All that would change with the outbreak of another war, the American Civil War. The excise tax on distilled spirits would be reimposed, and federal regulations would be put in place to ensure that those taxes were paid. In fact, distilling soon became the most regulated industry in the United States, and the taxes levied on it represented the largest source of income for the federal government until the creation of an income tax in 1913.

In August 1862, the federal government passed a $0.20 per proof gallon (i.e., one gallon of hundred-proof whiskey) excise tax on distilled spirits. As the war continued, the cost to the government increased, and, thus, the tax was increased, first to $0.60 per proof gallon in March 1864, next to $1.50 per proof gallon in July 1864, and then to $2.00 per proof gallon in January 1865.1 The original whiskey tax was paid as soon as the spirit left the still. But the law was changed in 1864 to allow a three-month bonding period (long enough for the wood to soak) before the tax was imposed.

After the war ended, the debt remained, and so did the tax on spirits. In July 1868, the government did offer some relief. This came in the form of a lowered tax rate—$0.50 per proof gallon—and a one-year bonding period for aging whiskey. The newly barreled whiskey was placed in a government-bonded warehouse for a year. After that year, “gaugers”—employees of the Internal Revenue Service—would measure the proof gallons in each barrel and only then determine the amount of tax owed, meaning that the distiller was no longer taxed on the liquid absorbed by the barrel.

However, the gaugers were guided in their determinations by an official manual that established a priori the amount of liquid that should be in a barrel after a year. All barrels were charged at least that amount, even if they actually contained less liquid, and barrels that contained more that the official amount were charged correspondingly more. For the government the situation was win-win. For the distillers it was cause for dissatisfaction. When the tax was increased to $0.70 per proof gallon in August 1872, many distillers began looking for a way to get around the system. The method they ultimately devised—collusion with the gaugers—led to the “Whiskey Ring” scandal of 1875.

The way in which the scam worked was that the distiller would make a full day’s run of whiskey but the gauger would record only half of it. The distiller would then sell the nonbonded whiskey, on which he had paid no tax, at the same price as he would have charged had he actually paid the appropriate tax, and he and the gauger would split the profit. This arrangement had the further advantage to the distiller of allowing him to cut the price he charged for whiskey on which he had paid tax since he could make up the difference with what he had earned on the tax-free product.

Proof Gallon

The federal excise tax is based on a “proof gallon” of spirits. By definition, a proof gallon is one gallon of one-hundred-proof spirits at sixty-eight degrees Fahrenheit. The temperature is important because the alcohol will expand or contract with variation in temperature. A distiller could lower the volume of alcohol for tax purposes by simply chilling the liquid a few degrees in the storage vat before bottling. Then, by letting the alcohol warm and expand before bottling, the distiller would have many extra gallons of tax-free bourbon to sell.

The proof gallon is the standard tax unit applied to distilled spirits. This means that one gallon of 80-proof whiskey is taxed at 80 percent of the current rate and that one gallon of 110-proof whiskey is taxed at 110 percent of the current rate.

The scandal broke shortly after the March 1875 excise tax increase—to $0.90 per proof gallon—when Benjamin H. Bristow, the secretary of the Treasury, discovered the widespread fraud that was taking place. In May 1875, the government seized sixteen distilleries in the Midwest and arrested 240 people, including distillers, gaugers, and other government employees. In fact, the scandal reached as high as O. E. Babcock, President Grant’s personal secretary. All the defendants faced charges of tax fraud and corruption.

The trials began in October 1875 in a courtroom in Jefferson, Missouri. Ultimately, Babcock was acquitted. (He would go on to write a tell-all book implying Grant’s involvement in the scandal, the money involved having supposedly been used to finance the president’s reelection campaign.) Still, over one hundred convictions were obtained and over $3 million in taxes recovered. And the distilling industry was subjected to increased regulation.

Bonded warehouses were now outfitted with two locks on their doors. The gauger had the key to one lock, the distiller the key to the other, and neither could open the warehouse without the other being present. Further, distilleries could contain no concealed pipes so that the gauger could ensure that no whiskey was being diverted. Finally, accurate records had to be kept on the amount of grain coming into the distillery and the amount of whiskey being made. The gaugers’ manual gave figures for how much whiskey could be produced per bushel of grain. Any discrepancies uncovered were immediately investigated. The government was determined to collect its taxes and avoid another scandal.

The distillers were not in principle opposed to regulations and taxes, which discouraged distilling on a small scale and favored larger producers with more capital. In fact, in some instances they even encouraged increased regulation. For example, because whiskey generally was not sold until it was three years old, in 1879 they arranged through their representatives in Washington, DC, to have the bonding period increased from one year to three. This move actually saved them money since, along with the liquid absorbed by the wood, evaporation also claims roughly 3 percent of a barrel’s contents each year.

Belmont and Astor Distilleries in Louisville, Kentucky, with their bonded warehouses, ca. 1890. (Courtesy United Distillers Archive)

Nevertheless, taxes and regulations took their financial toll on distillers, especially after 1894, when the tax increased to $1.10 per proof gallon and the bonding period increased to eight years (where it would remain until the 1950s). Also, straight whiskey distillers—producers of aged whiskey—had since the end of the Civil War been facing increased competition from producers of rectified whiskey, who often made what they passed off as ten-year-old whiskey in a single day. (It should be noted that many rectifiers made a quality product.) This flooding of the market with cheap rectified whiskey—much of it foreign in origin—led to declining straight whiskey prices.

Angel’s Share

When whiskey is being aged, evaporation through the pores of the oak barrel staves changes the proof of the whiskey. The degree to which the proof of the whiskey changes depends on where the whiskey is stored in the warehouse. If it is on one of the upper floors, the proof will increase with age; if it is on one of the lower floors, the proof will decrease with age. There is a point in the middle where the proof does not change. This change in proof is driven by heat. On the upper levels of the warehouse, where the temperature can be over one hundred degrees Fahrenheit in the summer, both alcohol and water vaporize, pressure builds up in the barrel, and water molecules, which are smaller than alcohol molecules, pass through the pores of the wood at a greater rate than do alcohol molecules, thus raising the proof of the whiskey. On the lower levels, where the temperature is much cooler—often in the midseventies even on a hot summer day—thanks to the updraft created by the rising hot air, more alcohol than water will vaporize, and more alcohol passes through the wood pores, thus lowering the proof of the whiskey.

The overproduction of whiskey, combined with the depression set off by the Panic of 1873, eventually forced many straight whiskey distillers into bankruptcy. The Pepper family was one such victim, selling the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery to the firm Labrot and Graham in 1878. Another was E. H. Taylor, who sold his OFC (or Old-Fashioned Copper) Distillery, which he had purchased in 1870, to Gregory and Stagg, a whiskey wholesaler based in St. Louis. Taylor eventually formed the firm E. H. Taylor Jr. and Sons and became a champion of straight whiskey and an active crusader against the ills of overproduction.

The Whiskey Trust

The end of the nineteenth century saw the organization of “trusts” or monopolies on goods in order to control prices. The whiskey industry was not immune to this trend. In May 1877, the Distillers’ and Cattle Feed Trust was formed. It was headquartered in Peoria, Illinois, and eventually encompassed sixty-five distilleries in several states, but mostly in Illinois and western and central Kentucky. It succeeded in controlling a large amount of whiskey production, but never enough to actually control the price of whiskey. There were simply too many distilleries making whiskey, and many of them were opposed to the idea of a trust. In the 1890s, the trust became the target of state and federal government antitrust actions. It would eventually be broken into three companies—Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Co., American Spirits Manufacturing Co., and Standard Distilling and Distributing Co. of America—under the parent company Distillers’ Securities Corp. It survived in this form until Prohibition. At the end of Prohibition, it emerged as National Distillers Corporation. (See William L. Downard, Dictionary of the History of the American Brewing and Distilling Industries [Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1980], 213–14.)

By the 1890s, the rectifiers, who continued to pass their product off as aged Kentucky bourbon, effectively controlled the whiskey market. In order to reclaim their fair share of the market, straight distillers began lobbying the federal government for a bottled-in-bond act. The concept of bottling in bond refers to spirits that have been produced and bottled in accordance with a set of legal regulations meant to ensure authenticity and quality. The regulations signed into law as the 1897 Bottled-in-Bond Act were that the spirit must be at least four years old, have been bottled at one hundred proof, be the product of one distillery and one distiller in one season, and be unadulterated (only pure water could be added) and that the labels on both the bottle and the shipping case must clearly identify the distillery where it was distilled and, if different, the distillery where it was bottled.2 Bonded whiskeys are, thus, distinct from straight whiskeys, which can be combinations of different bourbons made at different times and in different places.

Opposition to the bottled-in-bond legislation was strong. The producers of rectified whiskey claimed that it singled out straight whiskey—at least a certain type of straight whiskey—and gave the distillers an unfair advantage in the marketplace. The testimony before Congress of the rectifier Isaac Wolfe Bernheim is typical of the opposition. Bernheim argued that, because the name of the distiller had to be placed on both the bottle and the shipping case, even if the spirit was being made for another company, and because the practice of marrying different whiskeys was disallowed, the law would give the distillers an unfair advantage: “The blender of spirits receives no protection. The distillers, particularly those from Kentucky, intend and will, with the help of the government, be encouraged to monopolize the business.” He pointed out that the distillers had already attempted to bail themselves out of the consequences of what they saw as overproduction (and the rectifiers saw as healthy competition) by calling on the government to establish ever-longer bonding periods: “Distillers have called on Congress so liberally, that, like the helpless child, he constantly looks to the law making powers at Washington and in Kentucky, to rectify blunders and mistakes for which he alone should remedy.” The distillers should, he felt, have stayed out of the bottling business and simply sold to those firms that were rectifying whiskey.3

Isaac Wolfe Bernheim. (Courtesy United Distillers Archive)

Bottling line at the Old Judge Distillery, Frankfort, Kentucky, ca. 1903. (Courtesy United Distillers Archive)

In the event, the distillers presented the counterargument that the law would ensure the purity of American-produced whiskey and help protect it from competition by Canadian bottled-in-bond whiskeys. Their coalition, led by the Kentuckians Thomas Jones of the Kentucky Distillers’ Association, Edmund Taylor, the son of E. H. Taylor Jr., and James G. Carlisle, the secretary of the Treasury, won the day. President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law on March 3, 1897, the day before the newly elected William McKinley was sworn in as president.

Early Legal Challenge to the Rectifiers

The first legal challenge to the rectifiers came not from American distillers but from the government of Japan, which in 1869 objected to the practice of imported rectified whiskey being advertised as straight whiskey. The case ultimately came before the Ohio Circuit Court, the presiding judge, Alphonso Taft (the father of William Howard Taft), ruling that a product containing neutral spirits could not be called whiskey. While the decision did nothing to change U.S. law—the rectifiers continued to do business as usual— it did set a legal precedent that would influence the regulation of whiskey under the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

It took a number of years for the concept of bottled-in-bond whiskey to become well-known among the general public, even though public attention had been first drawn to the practice by Hiram Walker and Sons’ 1893 Chicago World’s Fair exhibit, which spotlighted the Canadian bottled-in-bond law, which had been passed in 1883. In fact, the passing of the Bottled-in-Bond Act went almost unnoticed until the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, where one feature of the Kentucky Building was a display sponsored by Kentucky distillers explaining the difference between bonded and nonbonded whiskey. From that time until Prohibition, sales of bottled-in-bond whiskey improved every year.

The war between the distillers and the rectifiers was not yet over, however. The two groups crossed swords again over the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act. The act had been prompted by the recent work of those investigative journals known as muckrakers who exposed the dangers to which the practices of many companies in the food and drug industries exposed consumers. Whiskey, which fell under its purview, was defined in it as straight whiskey. All other products were imitations or compounds and should be labeled as such. This set the stage for a fight that would last over three years.

The rectifiers challenged this definition of whiskey. They argued not only that their whiskey was whiskey but also that it was the most pure form of whiskey, straight whiskey being higher in congeners and fusel oils, many of which were poisonous. Canadian and British producers joined in the challenge since, if the definition were upheld, almost all Canadian and Scotch whiskey exported to the United States would have to be labeled as imitation. Straight whiskey producers countered that the rectifiers did, in fact, add substances to their products, that many of these substances were newly developed, that the long-term effects of these substances on the human body were unknown, and that even some of the more familiar substances (such as sulfuric acid) were known to be harmful.

Pure Food and Drug Act

President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) was a progressive-minded president who sought social reforms through government. One of these reforms was the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which prevented the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious foods, drugs, medicines and liquors” (William L. Downard, Dictionary of the History of the American Brewing and Distilling Industries [Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1980], 155). The act covered interstate and foreign commerce and had an impact on the spirits industry worldwide since, to sell their products in the United States, distillers had to follow the regulations established by the act.

These arguments were made before the courts and in magazines and newspapers around the country. Various interest groups took sides, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, for example, siding with the straight whiskey distillers because straight whiskey was at least an all-natural product and, thus, the lesser and safer of two evils. But it took three years for the issue to be settled.

In those three years the debate became so heated that President Taft agreed to make a decision on the issue. The two sides’ chosen representatives argued their cases before him, and in December 1909 he released his decision. Neutral spirits could be used in whiskey as long as they were grain neutral spirits; neutral spirits made from fruit or molasses were forbidden. Whiskey made by flavoring neutral spirits had to be labeled blended. Straight whiskey could be labeled as such, and descriptors such as bourbon and rye could be used to identify the dominant grain. Distillers of straight whiskey could also use the descriptor aged in wood, but, interestingly, so could Canadian Club, which was a mixture of neutral spirits and straight whiskey that had been aged in wood. Canadian Club was the only brand mentioned by name in the decision.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there was no need to ask the question, What is whiskey? The answer was obvious. Whiskey was spirits distilled from fermented grain. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the question What is whiskey? was being asked—and with increasing urgency. Was it straight whiskey? Was it blended whiskey? Or was it compound or imitation whiskey? The answer finally turned out to be: all of the above. And the distinctions set down in 1909 are followed faithfully today.