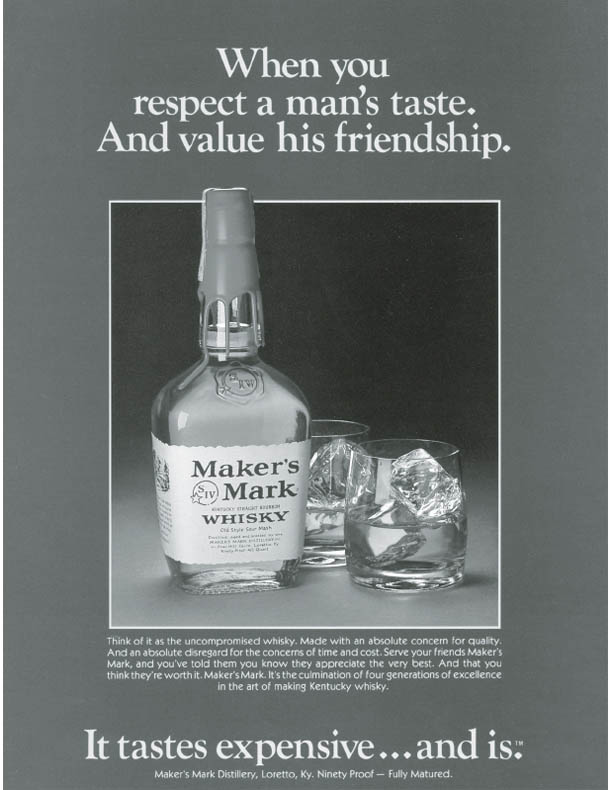

An advertisement for Maker’s Mark. (Courtesy Jim Beam Distillery)

The 1950s was the golden age of the Kentucky bourbon industry. There were no restrictions on production—beyond sales projections—and distillers were able to offer consumers a wide variety of products at reasonable prices. These innovations were sparked by a number of different factors.

Schenley’s Louis Rosenstiel perceived the outbreak of hostilities between North and South Korea as the beginning of another world war and ordered an increase in production to build up stocks before the government stepped in and once again stopped the production of beverage alcohol. He was wrong, of course, and found himself with warehouses overstocked with bourbon on which he would have to pay a huge tax bill in eight years. So he lobbied the government to increase the bonding period to twenty years. His efforts were successful, and the Forand Bill was passed in September 1958 to go into effect in July 1959.1

Distillers were now free to market older whiskeys. Schenley, for example, released ten- and twelve-year-old versions of Old Charter (“the whiskey that didn’t watch the clock”), a ten-year-old version of Ancient Age, and ten- and twelve-year-old versions of I. W. Harper. And Stitzel-Weller released ten-, twelve-, and fifteen-year-old versions of Old Fitzgerald. It also targeted an older market segment that remembered the pre-Prohibition whiskey that came straight from the barrel without a reduction in proof with its Weller Original Barrel Proof, a seven-year-old bourbon that initially varied in proof between 107 and 110 but eventually settled at 107.2

As the cold war heated up, the market for bourbon became international. Just as Scotch whiskey went global by following the armed forces of Britain to every corner of its empire, so too bourbon whiskey followed the U.S. military to its bases in South Korea, Japan, Germany, and Italy. Initially available only through base exchanges, bourbon was soon among the standard offerings of local bars catering to servicemen, giving the locals a chance to develop a taste for it as well.

American distilleries began marketing their products internationally. Schenley, for example, made I. W. Harper bourbon its international brand and brokered deals with distribution companies serving countries with an American military presence (and creating their own distribution companies where none existed). By 1966, after expanding into such Third World markets as Central and South America, I. W. Harper was being advertised in 110 countries worldwide.

Jim Beam, however, is the singular success story when it comes to international marketing. It had an initial advantage in that Jim Beam was one of the whiskeys made available by the U.S. Army in its base exchanges, and American soldiers became its unpaid salesmen. Jack Daniels gained a huge advantage when it caught on with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and the rest of the Rat Pack. The growth process was slow, and the competition from the Scotch whiskey industry was fierce— the fixed notion was that bourbon was a cheap alternative to Scotch—but eventually Jack Daniel’s Old No. 7 Tennessee whiskey would become the international industry leader. (Few foreign regulatory agencies recognize the difference between Tennessee whiskey, which is filtered through sugar maple charcoal before going into the barrel, and bourbon whiskey.)

Schenley of course jumped on the bandwagon of Old No. 7’s growing popularity. When it was unable to acquire the Jack Daniel’s Distillery (it was outbid by Brown-Forman), it launched its own brand of Tennessee whiskey. It had purchased the George Dickel Cascade bourbon brand in 1935, but, fearing the market confusion that would likely result if Cascade were brought back as a Tennessee whiskey, it launched George Dickel No. 8 and No. 12 instead.

The other big success story of the 1950s is Maker’s Mark. Having sold the family distillery and its brand in the 1940s, Bill Samuels Sr. wanted to get back in the business. So he bought the Burkes Spring Distillery, which he renamed the Star Hill Distillery, and set out to make a single, premium brand of bourbon. After testing several mash bills, he settled on one made of winter wheat instead of rye.3 He named his bourbon after his wife’s pewter collection (each piece of which had its own maker’s mark), had uniquely shaped, waxsealed bottles designed, and introduced Maker’s Mark to the market in 1959. The distillery had a limited capacity, so Samuels kept the market area small. Nevertheless, Maker’s Mark gained a reputation as a top-notch bourbon, in the process developing a loyal customer base that helped it retain its market share in the 1960s and beyond, even as other brands were losing theirs.

Why “No. 8” and “No. 12”

George Dickel No. 8 and George Dickel No. 12 were released under those brand names because consumer studies showed the numbers eight and twelve to be the most popular. Neither number has anything to do with the age of the whiskey.

Yet another marketing innovation to sweep the distilling industry in the 1950s was holiday packaging. Some of the best designers of the day were hired to create special bottles—more like decanters and often with stoppers that doubled as jiggers. The packaging was festive—although keeping within the industry’s self-imposed regulations for advertising—and often featured cocktail recipes. The effort was so successful that by the 1960s the glass decanters had been replaced by ceramic decanters, which in some markets were offered year-round. Jim Beam in particular was deeply invested in this marketing strategy, producing decanters depicting everything from cars and trucks, to animals, to famous opera characters, as well as celebrating various commemorative themes. But other distillers cashed in on the craze as well. George Dickel came out with a 110th anniversary powderhorn bottle, I. W. Harper had its bowing-man decanter with gray pants and top hat for southern markets and blue pants for northern, and Early Times released a series of decanters shaped like all fifty states of the Union. Decanters became so popular that nondistillers sometimes got in on the action by purchasing bulk whiskey and bottling it in ceramic decanters. Clubs were formed, and collecting ceramic decanters became a hobby in its own right.

The bourbon industry roared into the 1960s with a strong domestic market share and a growing international market. And things seemed only to be looking up when in 1964 the U.S. Congress recognized bourbon as “a distinctive product of the United States” just as Scotch whiskey, Canadian whiskey, and cognac were distinctive products of Scotland, Canada, and France, respectively. Its resolution stipulated that “to be entitled to the designation ‘bourbon whiskey’ the product must conform to the highest standards and must be manufactured in accordance with the laws and regulations of the United States which prescribe a standard of identity for ‘bourbon whiskey’” and instructed that “the appropriate agencies of the United States Government . . . will take appropriate action to prohibit the importation into the United States of whiskey designated as ‘bourbon whiskey.’”4

But the mood of the nation changed dramatically as the decade progressed. The Vietnam War created a generation of rebellious young people who rejected anything and everything their parents stood for, including their alcoholic beverage choices. They turned away from whiskey to beer and wine, vodka and tequila, the latter two being spirits that until this time had only a very small share of the American market. Irish and rye whiskey sales had already been in decline as sales of Scotch and bourbon grew steadily stronger in the 1940s and 1950s; now whiskey sales across the board plummeted.

The distilling industry was caught between a rock and a hard place. It was losing the youth market, but it feared being accused of promoting underage drinking by targeting it. Also, because of its self-regulation, it could not match the radio and television advertising that the wine and beer industries employed. And, because sales predictions had to be made four, eight, even twelve years in advance, the surprising drop-off in market share left it with warehouses overstocked with a product that was not moving. Once again, the smaller companies began to go out of business.

The bigger, better capitalized companies fared somewhat better. Schenley, for example, managed to stay afloat because it had continued to expand, in the 1950s purchasing Blatz beer and investing in such products as Canadian whiskey, rum, cordials, and wine. But expansion was not the only route to survival. Maker’s Mark remained prosperous precisely because it continued to produce a high-quality product and kept its markets close to home and small. And Jack Daniel’s capitalized on its reputation as the drink of choice of the rebellious Rat Pack and successfully appealed to the younger generation, becoming popular among the hard rock crowd and motorcycle clubs.

The boom had gone bust. The major players in the industry were changing as the old guard died off, and the young turks who took their place took the industry in a different direction. The American whiskey market looked bleak, but change was once again on the horizon.