35

THE FRENCH COLLECTION

On the evening of 31 January 1977, at twenty minutes past eight, regardless of who had arrived and who had not, the doors to the Galérie Beaubourg, the Centre Nationale d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou, in central Paris, were shut tight. President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was about to make a speech, declaring the Pompidou Centre open, and there was no escape. Men in black tie and women in long dresses were milling on all floors, many searching for a drink – in vain, as the president, for reasons best known to himself, had decreed that there should be no refreshments. When he delivered his speech, Giscard began with a tribute to Pompidou (a former president of the French republic, who had nursed the project), snubbed Jacques Chirac, the mayor of Paris and the man in charge of the department that had commissioned the centre, and made no mention of either the building’s designers or builders. Forced to listen to the president without a glass in their hands, the assembled guests wondered whether the omissions in his speech meant that he didn’t like the building.1

Many didn’t. Many thought that the Pompidou Centre was then, and still is, the ugliest building ever constructed. Whatever the truth of this, its importance cannot be doubted.2 In the first place, it was intended not just as a gallery or museum but as an arts complex and library, designed to help Paris regain its place as a capital of the arts, a tide it had lost since World War II and the rise of New York. Second, the centre was important architecturally because whatever its appearance, it undoubtedly marked a robust attempt to get away from the modernist aesthetic that had predominated since the war. And third, it was important because the centre also housed IRC AM, the Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique, which was intended to become a world centre for experimental music. The directorship of IRCAM was offered to Pierre Boulez, to lure him back from America.3

But the significance of ‘Beaubourg’ was predominantly architectural. Its designers were Renzo Piano, an Italian, and Richard Rogers, from London, two of the most high-tech-minded men of the times, while the jury who selected them included Philip Johnson, Jørn Utzon, and Oscar Niemayer, respectively American, Danish, and Brazilian architects who had between them been responsible for some of the most famous buildings constructed since the war. Philip Johnson represented the mainstream of architecture as it had followed on from the Bauhaus – Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier. In the thirty years between 1945 and 1975 most Western architecture was dominated, functionally, by two matters: the corporate building and mass housing. Following the International style (a term coined by Philip Johnson himself), architecture had devised solutions mainly by means of straight lines and flat planes, in buildings that were often either wholly black (as with Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram’s Tower in Manhattan) or, more usually, wholly white (as with countless housing projects). Despite heroic attempts to escape the tyranny of the straight line (zigzags, diamonds, lozenges, most notably successful in the building boom of new universities in the 1960s), too often modern architecture had resulted in what Jane Jacobs famously called the ‘great blight of dullness,’ or what the critic Reyner Banham labelled the ‘new brutalism.’ The problem, as identified by the Italian critics Manfredo Tafuri and Francesco Dal Co, was an ‘obsessive preoccupation with restoring meaningful depth to a repertory of inherited forms that are devoid of meaning in themselves.’4 The South Bank Complex in London (the ensemble that houses the National Theatre) and the Torre Velasca, near the Duomo in Milan, are good examples of these massive buildings, which feel almost menacing.

Niemayer and Utzon were notable for at least trying to break away from this tradition. Niemayer trained with Le Corbusier and became famous for his curved, shell-like concrete roofs, most notably in the new Brazilian capital, and vistas reminiscent of Giorgio de Chirico. Jørn Utzon designed many housing projects, but his most famous building was Sydney Opera House, in Australia, which, in its white, billowing roofs, sought to recapture the line of the sailing ships that had first discovered Australia not so very long before. Here too, though undoubtedly popular with the public (and without question strikingly original), the Opera House was perhaps too much of a one-off in function and location (on the waterfront, where it could be easily seen) to be widely imitated. Nevertheless, for all their faults, Niemayer and Utzon had tried hard to get away from the conventional architectural wisdom epitomised by Johnson, and in theory that made the Beaubourg jury a good one, the more so as it also included Wilhelm Sandberg, curator of the Stedelijk (Modern Art) Museum in Amsterdam, and widely regarded as the most important museum curator of the century (though Alfred Barr would surely run him close). They considered 681 valid submissions, which they reduced first to 100, then to 60, and finally to project 493 (all drawings were considered anonymously): Messrs Piano, Rogers, Franchini, architects; and Ove Arup and Partners, consultant engineers (who had worked both on the South Bank Complex and Sydney Opera House).5

Renzo Piano, born in 1937, was Genoese and did not consider himself only an architect but also an industrial designer – Olivetti were one of his clients. Richard Rogers was born in England in 1933 but came from a family that was mainly Italian – his cousin, Ernesto Rogers, taught Piano in Milan. A Fulbright scholar, Rogers had studied at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, and then at Yale, where he met his one-time partner Norman Foster, and Philip Johnson. Piano and Rogers’ winning design had two main features. It did not use up all the space, an area of Paris of about seven acres that had been cleared many years before. Instead, a rectangle was left free in front of the main building for a piazza, not simply for tourists but for street theatre – jugglers, fire eaters, acrobats, and so on. A more controversial feature of the building was that its ‘innards,’ essentially the parts of a building that are usually hidden, such as the ducts for air conditioning, plumbing, and elevator motor rooms, were on the outside, and brightly painted, turned into a prominent design feature. One reason for this was flexibility: the building was expected to develop in the future, and the existing machinery might need to be changed.6 Another reason was to avoid the idea that yet another ‘monument’ was being erected in Paris. By exposing those elements that would normally be hidden, the ‘industrial’ aspects of the centre were highlighted, making the building more urban.

An escalator also snaked up the building, on the outside, covered in a glass tube. This feature especially appealed to Philip Johnson.7 The Pompidou Centre was only a shoebox festooned in ducts; yet it looked like nothing that had gone before, and certainly not like an international modern building. Like it or loathe it, Pompidou was different, and a mould was broken. It didn’t inspire many copies, but it was a catalyst for change.

IRCAM was part of the specifications for the Pompidou Centre. The brief was to make it the world’s pre-eminent centre for musical technology, with special studios that had absolutely no echo, advanced computers, and acoustical research laboratories, plus a hall for performances that would seat up to 500. This centre, which became known as ‘Petit Beaubourg,’ was originally conceived on five underground levels, with a glass roof, a library, and, in the words of Nathan Silver, the Pompidou’s historian, ‘studios for musical researchers from all over the world.’8 It was cut back after Giscard became president, but even so it was enough to entice Boulez home.

Pierre Boulez was born in 1925. He was one of a handful of composers – Karlheinz Stockhausen, Milton Babbitt, and John Cage were others – who dominated musical innovation in the years after World War II. In the 1950s, as we have seen, serious composers had followed three main directions – serialism, electronics, and the vagaries of chance in composition. Boulez, Stockhausen, and Jean Barraqué had all been pupils of Olivier Messiaen. He, it will be recalled from chapter 23, had tried to write down the notes of birdsong, believing that all forms of sound could be made into music, and this was one important way he exerted an influence on his pupils. Stockhausen in particular was impressed by the music of Africa, Japan (where he worked in 1966), and South America, but Boulez too, in Le Marteau sans maitre (The Hammer Unmastered), 1952–4, scored for vibraphone and xylorimba, used the rhythms of black African music. Serialism in the late compositions of Anton von Webern, who had died in 1945, was just as influential, however. Boulez described these compositions as ‘the threshold,’ and Stockhausen agreed, as did Milton Babbitt in America. In Europe the centre of this approach was the Kranichstein Institute in Darmstadt, where in the summer months composers and students met to discuss the latest advances. Stockhausen was a regular.9

Boulez was perhaps the most intellectual in a field that was, more than most, dominated by theory. For him, serialism was a search for ‘an objective art of sound.’ He saw himself as a scientist, an architect, or an engineer of sound as much as a composer. In a paper entitled ‘Technology and the Composer,’ he lamented the conservative tendencies in music which had, as he saw it, prohibited the development of new musical instruments, and this is why, according to the critic Paul Griffiths, he thought Messiaen’s approach, electronic music, and the computer so important to the advance of his art form.10 As one of his most famous compositions, Structures, shows, he was also concerned with ‘structure,’ which, he wrote, was ‘the key word of our time.’ In his writings Boulez made frequent references to Claude Lévi-Strauss, the Bauhaus, Ferdinand Braudel, and Picasso, each of which was a model. He had frequent meetings, some of them in public, with Jacques Lacan and Roland Barthes (see below). In a celebrated remark, he said that it was not enough to add a moustache to the Mona Lisa: ‘It should simply be destroyed.’ In order to do this, he rigorously pursued new forms of sound, where ‘research’ and mathematical patterns were not out of place.11 Both Boulez and Cage used charts of numbers in setting up rhythmic structures.

Electronic music, including the electronic manipulation of natural sounds, metallic and aqueous (musique concrète), provided yet another avenue to explore, one that offered both new structures and a seemingly scientific element that was popular with this small group. New notations were devised, and new instruments, in particular Robert Moog’s synthesiser, which arrived on the market in 1964, bringing with it a huge variety of new electronically generated sounds. Babbitt and Stockhausen both wrote a great deal of electronic music, and the latter even had a spherical auditorium (for maximum effect) built for him at the 1970 Osaka exhibition.

Chance in music was described by Paul Griffith as the equivalent of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings in art, and the swaying ‘mobiles’ of Alexander Calder in sculpture.12 In America John Cage was the leading exponent; in Europe, chance arrived at Darmstadt in 1957, with Stockhausen’s Klavierstück XI and Boulez’s Piano Sonata no. 3. In Stockhausen’s composition the musician was presented with a single sheet of paper containing nineteen fragments that could be played in any order. Boulez’s work was less extreme: the piece was fully notated, but the musician was forced to make a choice of direction at various points.13

Boulez epitomised the radical character of these postwar composers, even to the extent that he questioned everything to do with music – the nature of concerts, the organisation of orchestras, the architecture of concert halls, above all the limitations imposed by existing instruments. It was this that led to the idea of IRCAM. John Cage had tried something similar in Los Angeles in the early 1950s, but Boulez didn’t float the idea until May 1968, a revolutionary moment in France.14 He was ambitious in his aims (he once said, ‘What I want to do is to change people’s whole mentality’). It is true, too, that Boulez, more than anyone else of his generation, more even than Stockhausen, saw himself in a sense in a ‘Braudelian’ way, as part of la longue durée, as a stage in the evolution of music. This was why he wanted IRCAM to make music more ‘rational’ (his word) in its search for creativity, in its employment of machines, like the ‘4X,’ which was capable of ‘generating’ music.15 In May 1977, in the Times Literary Supplement, Boulez set out his views. ‘Collaboration between scientists and musicians – to stick to those two generic terms which naturally include a large number of more specialised categories – is therefore a necessity that, seen from the outside, does not appear to be inevitable. An immediate reaction might be that musical invention can have no need of a corresponding technology; many representatives of the scientific world see nothing wrong with this and justify their apprehensions by the fact that artistic creation is specifically the domain of intuition, of the irrational. They doubt whether this Utopian marriage of fire and water would be likely to produce anything valid. If mystery is involved, it should remain a mystery: any investigation, any search for a meeting point is easily taken to be sacrilege. Uncertain just what it is that musicians are demanding from them, and what possible terrain there might be for joint efforts, many scientists opt out in advance, seeing only the absurdity of the situation.’16 But, he goes on, ‘In the end, musical invention will have somehow to learn the language of technology, and even to appropriate it…. A virtual understanding of contemporary technology ought to form part of the musician’s invention; otherwise, scientists, technicians and musicians will rub shoulders and even help one another, but their activities will only be marginal one to the other. Our grand design today, therefore, is to prepare the way for their integration and, through an increasingly pertinent dialogue, to reach a common language that would take account of the imperatives of musical invention and the priorities of technology…. Future experiments, in all probability, will be set up in accordance with this permanent dialogue. Will there be many of us to undertake it?’17

The French Connection, William Friedkin’s 1971 film about the Mafia and drug running into America, wasn’t really about France (some of the villains are French-speaking Canadians), but the film’s title did catch on as a description of something that was notable in philosophy, psychology, linguistics, and epistemology just as much as in historiography, anthropology, and music. This was a marked divergence between French thought and Anglo-Saxon thought that proved fruitful and controversial in equal measure. In the United States, Britain, and the rest of the English-speaking world, the Darwinian metanarrative was in the ascendant. But in France in particular the late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s also saw a resurgence of the other two great nineteenth-century metanarratives: Freudianism and Marxism. It was not always easy to distinguish between these theories, for several authors embraced both, and some – generally French but also German – wrote in such a difficult and paradoxical style that, especially after translation, their language was extremely dense and often obscure. In the sections that follow, I have relied on the accessible commentaries quoted, in addition to the works themselves, in an effort to circumvent their obscurity. These French thinkers do represent a definite trend.

Jacques Lacan was a psychoanalyst in the Freudian tradition, who developed in highly idiosyncratic ways. Born in 1901 in Paris, in the 1930s Lacan attended Alexandre Kojève’s seminars on Hegel and Heidegger, along with Raymond Aron, Jean-Paul Sartre, André Breton, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Raymond Queneau (see chapter 23). Psychoanalysis was not taken up as quickly in France as in the US, and so it wasn’t until Lacan began giving his public seminars in 1953, which lasted for twenty-six years, that psychoanalysis in France was taken seriously. His seminars were intellectually fashionable, with 800 people crammed into a room designed for 650, with many prominent intellectuals and writers in the audience. Although the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser thought enough of Lacan to invite him in 1963 to transfer his seminar to the Ecole Normale Supérieure, Lacan was forced to resign from the Société Psychoanalytique de Paris (SPP) and was expelled from the International Psychoanalytic Association, because of his ‘eclectic’ methods. After May 1968, the Department of Psychoanalysis at Vincennes (part of Paris University) was reorganised as Le Champ Freudien with Lacan as scientific director. Here was the mix of Freudianism and Marxism in action.18

Lacan’s first book, Ecrits (Writings), published in 1966, contained major revisions of Freudianism, including the idea that there is no such thing as the ego.19 But the aspect of Lacan’s theory that was to provoke widespread attention, and lead on from Ludwig Wittgenstein and R. D. Laing, was his attention to language.20 Like Laing, Lacan believed that going mad was a rational response to an intolerable situation; like Wittgenstein, he believed that words are imprecise, meaning both more and less than they appear to mean to either the speaker or the hearer, and that it was the job of the psychoanalyst to understand this question of meaning, as revealed through language, in the light of the unconscious. Lacan did not offer a cure, as such; for him psychoanalysis was a technique for listening to, and questioning, ‘desire.’ In essence, the language revealed in psychoanalytic sessions was the language of the unconscious uncovering, ‘in tortured form,’ desire. The unconscious, says Lacan, is not a private region inside us. It is instead the underlying and unknown pattern of our relations with one another, as mediated by language. Influenced by surrealism, and by the linguistic theories of Ferdinand de Saussure, Lacan became fascinated by the devices of language. For him there are ‘four modes of discourse’ – those of the master, the university, the hysteric, and the psychoanalyst, though they are rarely seen in pure form, the categories existing only for the purpose of analysis. A final important concept of Lacan was that there is no such thing as the whole truth, and it is pointless waiting until that point has been reached. Lacan liked to say that the patient terminates his psychoanalytic treatment when he realises that it can go on for ever. This is the use of language in the achievement of meaning: language brings home to the patient the true nature – the true meaning – of his situation. This is one reason, say Lacan’s followers, why his own writing style is so dense and, as we would normally describe it, obscure. The reader has to ‘recover’ his own meaning from the words, just as a poet does in composing a poem (though presumably a poet’s recovered meanings are more generally accessible than the patient’s).21 This is of course an oversimplification of Lacan’s theories. Toward the end of his life he even introduced mathematical symbols into his work, though this does not seem to have made his ideas much clearer for most people, and certainly not for his considerable number of critics, who believe Lacan to have been eccentric, confused, and very wrong. Not least among the criticisms is that despite a long career in Paris, in which he made repeated attempts to synthesise Freud with Hegel, Spinoza, Heidegger, and the existentialism of Sartre, he nevertheless ignored the most elementary developments in biology and medicine. Lacan’s enduring legacy, if there is one, was to be one of the founding fathers of ‘deconstruction,’ the idea that there is no intrinsic meaning in language, that the speaker means more and less than he or she knows, and that the listener/hearer must play his or her part. This is why his ideas lived on for a time not just in psychology but in philosophy, linguistics, literary criticism, and even in film and politics.

Among psychiatrists, none was so political and influential as Michel Foucault. His career was as interesting as his ideas. Born in Poitiers, in October 1926, Paul-Michel Foucault trained at the Ecole Normale Supérieure. One of les grandes écoles, the ENS was especially grand, all-resident, its graduates known as normaliens, supplying universities with teachers. There Foucault came under the friendship, protection, and patronage of Louis Althusser, a slender man with ‘a fragile, almost melancholy beauty.’ Far from well, often in analysis and even electroshock treatment, Althusser had a huge reputation as a grand theorist.22 Foucault failed his early exams – to general consternation – but after he developed an interest in psychiatry, especially in the early years of the profession and its growth, his career blossomed. The success of his books brought him into touch with very many of the luminaries of French intellectual culture: Claude Lévi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Ferdinand Braudel, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jacques Derrida, and Emmanuel le Roy Ladurie. Following the events of 1968, he was elected to the chair in philosophy at the new University of Vincennes.23 The University of Vincennes, officially known as the Vincennes Experimental University Centre, ‘was the offspring of May 1968 and Edgar Faure,’ the French minister for education. ‘It was resolutely interdisciplinary, introduced novel courses on cinema, semiotics and psychoanalysis, and was the first French university to open its doors to candidates who did not have the baccalauréat.’ ‘It therefore succeeded in attracting (for a time) many wage earners and people outside the normal university recruitment pool.’ ‘The atmosphere … was like a noisy beehive.’24 This aspect of Foucault’s career, plus his well-publicised use of drugs, his involvement with the anti-Vietnam protests, his part in the campaign for prison reform, and his role in the gay liberation movement, show him as a typical central figure in the counter-culture. Yet at the same time, in April 1970 Foucault was elected to the Collège de France, a major plank in the French establishment, to a chair in the History of Systems of Thought, specially created around him. This reflected the very substantial body of work Foucault had amassed by that stage.25

Foucault shared with Lacan and Laing the belief that mental illness was a social construct – it was what psychiatrists, psychologists, and doctors said it was, rather than an entity in itself. In particular, he argued that modern societies control and discipline their popularions by delegating to the practitioners of the human sciences the authority to make these decisions.26 These sciences of man, he said, ‘have subverted the classical order of political rule based on sovereignty and rights and replaced them with a new regime of power exercised through the stipulation of norms for human behavior’. As Mark Philp has put it, we now know, or think we know, what ‘the normal child’ is, what ‘a stable mind’ is, a ‘good citizen,’ or the ‘perfect wife.’ In describing normality, these sciences and their practitioners define deviation. These laws – ‘the laws of speech, of economic rationality, of social behavior’ – define who we are. For Foucault, this idea, of ‘man as a universal category, containing within it a “law of being,” is … an invention of the Enlightenment’ and both mistaken and unstable. The aim of his books was to aid the destruction of this idea and to argue that there is no ‘single, cohesive human condition.’ Foucault’s work hung together with a rare consistency. His most important books examine the history of institutions: Madness and Civilisation: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (1964); The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969); The Order of Things : An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1971); The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (1972); Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975); The History of Sexuality (1976).

But Foucault was not just writing a history, of psychiatry, penology, economics, biology, or philology, as the case may be. He was seeking to show how the way knowledge is organised reflects the power structures within a society and how the definition of the normal man, or mind, or body, is as much a political construct as one that reflects ‘the truth.’27 ‘We are subject to the production of truth through power,’ Foucault wrote. It is the human sciences, he says, that have given us the conception of a society as an organism ‘which legitimately regulates its population and seeks out signs of disease, disturbance and deviation so that they can be treated and returned to normal functioning under the watchful eye of one or other policing systems.’ Again, as Philp has emphasised, these are revealingly known as ‘disciplines.’ Foucault calls his books ‘archaeologies’ rather than histories because, as Lacan saw meaning as a ‘recovering activity,’ Foucault saw his work too as an excavation that not only describes the processes of the past but goes beyond, to recreate ‘buried’ knowledge. There was something of l’homme revolté about Foucault; he believed that man could only exist if he showed a ‘recalcitrance’ towards the normative pressures of the human sciences, and that there is no coherent or constant human ‘condition’ or ‘nature,’ no rational course to history, no ‘gradual triumph of human rationality over nature.’ There is struggle, but it is ‘patternless.’ His final argument in this vein was to show that bourgeois, humanistic man had ‘passed.’ Liberal humanism, he said, was shown up as a sham, disintegrating as it revealed itself as an instrument of class power and the socially privileged.28 The individual subject, with a conscience and reason, is out-of-date in the modern state, intellectually, morally, and psychologically deconstructed.

Foucault’s last important book was an investigation of the history of sexuality, in which he argued that but for rape and sex with children, there should be no restraint on behavior. This was entirely in line with the rest of his oeuvre, but for him it had the unfortunate consequence that the development of gay bars and bathhouses, of which he positively approved (he adored California and went there a lot), were probably responsible for the fact that he died, in June 1984, of an AIDS-related illness.

From psychiatry to psychology: Jean Piaget, the Swiss psychologist, was not only interested in child development and the systematic growth of intelligent behavior. Later in life, his interests widened, and using the ideas of Foucault and Lacan, he became a leading advocate of a mode of thought known as structuralism. Piaget’s arguments also drew on the work of Noam Chomsky, but structuralism was really a concept developed in continental, and especially francophone, Europe, largely in ignorance of more empirical findings in the Anglo-Saxon, English-speaking world. This is one reason why many people outside France do not find it easy to say what structuralism is. Piaget’s Structuralism (1971) was one of the clearer expositions.29 Just as Foucault used the word archaeology; rather than history, to imply that he was uncovering something – structures – that already existed, so Piaget implied that there are ‘mental structures’ that exist midway between genes and behavior. One of his starting points, for example, is that ‘algebra is not “contained” in the behavior of bacteria or viruses’ and – by implication, because they are relatively similar – in genes.30 The capacity to act in a mathematical way, either as a bacterium (in dividing), or in the human, by adding and subtracting, is according to Piaget only partially inherited. Part of the ability arises from mental structures built up as the organism develops and encounters the world. For Piaget the organisation of grammar was a perfect example of a mental structure, in that it was partly inherited and partly ‘achieved,’ in the sense that Lacan thought patients achieved meaning in analysis.

‘If asked to “locate” these structures,’ Piaget writes, ‘we would assign them a place somewhere midway between the nervous system and conscious behavior’ (wherever that might be).31 To add to the confusion, Piaget does not claim that these structures actually exist physically in the organism; structures are theoretic, deductive, a process. In his book he ranges widely, from the mathematical ideas of Ludwig von Bertalanffy, to the economics of Keynes, to Freud, to the sociology of Talcott Parsons. His main concern, however, is with mental structures, some of which, he believes, are formed unconsciously and which it is the job of the psychologist to uncover. Piaget’s aim, in drawing attention to these mental structures, was to show that human experience could not be understood either through the study of observable behavior or through physiological processes, that ‘something else’ was needed.32 Piaget, more than most of his continental counterparts, was aware of the contemporary advances being made in evolutionary biology and psychology: no one could accuse him of not doing the work. But his writings were still highly abstract and left a lot to be desired in the minds of his Anglo-Saxon critics.33 So Piaget regarded the perfect life as an achieved structure, within biological limits but creatively individual also. The mind develops or matures, and the process cannot be hurried. One’s understanding of life, as one grows up, is mediated by a knowledge of mathematics and language – two essentially logical systems of thought – which help us handle the world, and in turn help organise that world. For Piaget, the extent to which we develop our own mental constructs, and the success with which they match the world, affects our happiness and adjustment. The unconscious may be seen as essentially a disturbance in the system that it is the job of the psychoanalyst to resolve.

After the success of structuralism, it was no doubt inevitable that there should be a backlash. Jacques Derrida, the man who mounted that attack, was Algerian and Jewish. In 1962, at independence, the Jews in Algeria left en masse: France suddenly had the largest Jewish population on the continent, west of Russia.

Derrida began with a specific attack on a specific body of work. In France in the 1960s, Claude Lévi-Strauss was not merely an anthropologist – he had the status of a philosopher, a guru, someone whose structuralist views had extended well beyond anthropology to embrace psychology, philosophy, history, literary criticism, and even architecture.34 We also have Lévi-Strauss to thank for the new term ‘human sciences,’ sciences of the human, which he claimed had left behind the ‘metaphysical preoccupations of traditional philosophy’ and were offering a more reliable perspective on the human condition. As a result, the traditional role of philosophy as ‘the privileged point of synthesis of human knowledge’ seemed increasingly vitiated: ‘The human sciences had no need of this kind of philosophy and could think for themselves.’35 Among the people to come under attack were Jean-Paul Sartre and the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. Lévi-Strauss belittled the ‘subjectivist bias’ of existentialism, arguing that a philosophy based on personal experience ‘can never tell us anything essential either about society or humanity.’ Being an anthropologist, he also attacked the ethnocentric nature of much European thought, saying it was too culture-bound to be truly universal.

Derrida took Lévi-Strauss to task – for being imprisoned within his own viewpoint in a much more fundamental way. In Tristes Tropiques, Lévi-Strauss’s autobiographical account of how and why he chose anthropology and his early fieldwork in Brazil, he had explored the link between writing and secret knowledge in primitive tribes like the Nambikwara.36 This led Lévi-Strauss to the generalisation that ‘for thousands of years,’ writing had been the privilege of a powerful elite, associated with caste and class differentiation, that ‘its primary function’ was to ‘enslave and subordinate.’ Between the invention of writing and the advent of science, Lévi-Strauss said, there was ‘no accretion of knowledge, just fluctuations up and down.’37

Derrida advanced a related but even more fundamental point. Throughout history, he said, writing was treated with less respect than oral speech, as somehow less reliable, less authoritative, less authentic.38 Combined with its ‘controlling’ aspects, this makes writing ‘alienating,’ doing ‘violence’ to experience. Derrida, like Lacan and Foucault especially, was struck by the ‘inexactitudes and imprecisions and contradictions of words,’ and he thought these shortcomings philosophically important. Going further into Lévi-Strauss’s text, he highlighted logical inconsistencies in the arguments, concepts that were limited or inappropriate. The Nambikwara, Derrida says, have all sorts of ‘decorations’ that, in a less ethnocentric person, might be called ‘writing.’ These include calabashes, genealogical trees, sketches in the soil, and so on, all of which undoubtedly have meaning. Lévi-Strauss’s writing can never catch these meanings, says Derrida. He has his own agenda in writing his memoir, and this leads him, more or less successfully, to write what he does. Even then, however, he makes mistakes: he contradicts himself, he makes things appear more black and white than they are, many words only describe part of the things they refer to. Again, all common sense. But again Derrida is not content with that. For him, this failure of complete representation is as important as it is inevitable. For Derrida, as with Lacan, Foucault, and Piaget, language is the most important mental construct there is, something that (perhaps) sets man apart from other organisms, the basic tool of thought and therefore essential – presumably – to reason (though also of corruption).39 For Derrida, once we doubt language, ‘doubt that it accurately represents reality, once we are conscious that all individuals are ethnocentric, inconsistent, incoherent to a point, oversimplifiers … then we have a new concept of man.’ Consciousness is no longer what it appears to be, nor reason, nor meaning, nor – even – intentionality.40 Derrida questions whether any single utterance by an individual can have one meaning even for that person. To an extent, words mean both more and less than they appear to, either to the person producing them or someone hearing or reading them.

This gap, or ‘adjournment’ in meaning, he labelled the différance and it led on to the process Derrida called ‘deconstruction,’ which for many years proved inordinately popular, notorious even. As Christopher Johnson says, in his commentary on Derrida’s ideas, deconstruction was an important ingredient in the postmodern argument or sensibility, enabling as many readings of a text as there are readers.41 Derrida wasn’t being entirely arbitrary or perverse here. He meant to say (in itself dangerous) not only that people’s utterances have unconscious elements, but also that the words themselves have a history that is greater than any one person’s experience of those words, and so anything anyone says is almost bound to mean more than that person means. This too is no more than extended common sense. Where Derrida grows controversial, or non-commonsensical, is when he argues that the nature of language robs even the speaker of any authority over the meaning of what he or she says or writes.42 Instead, that ‘meaning resides in the structure of language itself: we think only in signs, and signs have only an arbitrary relationship to what they signify.’43 For Derrida, this undermines the very notion of philosophy as we (think we) understand it. For him there can be no progress in human affairs, no sense in which there is an accumulation of knowledge ‘where what we know today is “better,” more complete, than what was known yesterday.’ It is simply that old vocabularies are seen as dead, but ‘that too is a meaning that could change.’ On this account even philosophy is an imprecise, incoherent, and therefore hardly useful word.

For Derrida, the chief aspect of the human condition is its ‘undecided’ quality, where we keep giving meanings to our experience but can never be sure that those meanings are the ‘true’ ones, and that in any case ‘truth’ itself is an unhelpful concept, which itself keeps changing.44 ‘Truth is plural.’ There is no progress, there is no one truth that, ‘if we read enough, or live life enough, we can finally grasp: everything is undecided and always will be.’ We can never know exactly what we mean by anything, and others will never understand us exactly as we wish to be understood, or think that we are being understood. That (maybe) is the postmodern form of anomie.

Like Derrida, Louis Althusser was born in Algeria. Like Derrida, says Susan James, he was more Marxist than Marx, believing that not even the great revolutionary was ‘altogether aware of the significance of his own work.’ This led Althusser to question the view that the world of ideology and the empirical world are related. For example, ‘the empirical data about the horrors of the gulag do not necessarily lead one to turn against Stalin or the USSR. ‘For Althusser, thinking along the same lines as Derrida, empirical data do not carry with them any one meaning; therefore one can (and Althusser did) remain loyal to, say, Stalin and the ideology of communism despite disparate events that happened inside the territory under Stalin’s control. Althusser also took the view that history is overdetermined: so many factors contribute to one event, or phenomenon – be they economic, social, cultural, or political – that it is impossible to specify causes: ‘There is, in other words, no such thing as a capability of determining the cause of a historical event. Therefore one can decide for oneself what is at work in history, which decision then constitutes one’s ideology. Just as economic determinism cannot be proved, it cannot be disproved either. The theory of history is something the individual works out for himself; necessarily so, since it does not admit of empirical and rational démonstration.’45 In any case, Althusser says, individuals are so much the creation of the social structures they inhabit that their intentions are to be regarded as consequences, rather than causes, of social practice.46 More often than not, all societies – and especially capitalist societies – have what he calls Ideological State Apparatuses: the family, the media, schools, and churches, for example, which propagate and receive ideas, so much so that we are not really self-conscious agents. ‘We acquire our identity as a result of the actions of these apparatuses.’47 In Marxist terms, the key to Althusser is the relative autonomy of the superstructure, and he replaced the false consciousness of class, which Marx had made so much of, and ‘substituted the false consciousness of ideology and individual identity, the aim being to shake people out of their ideological smugness and create a situation where change could be entertained.’48 Unfortunately, his published ideas stopped in 1980 after he murdered his wife and was declared unfit to stand trial.

With their scepticism about language, especially as it relates to knowledge and its links with power in the search for meaning, structuralism and deconstruction are the kin of cultural studies, as outlined by Raymond Williams, with Marx looming large in the background. Taken together they amount to a criticism of both capitalist/materialist society and the forms of knowledge produced by the natural sciences.

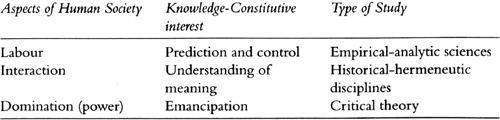

The most frontal attack on the sciences also came from the continent, by Jürgen Habermas. Habermas is the latest major philosopher in the tradition of the Frankfurt School, the school of Horkheimer, Benjamin, Adorno, and Marcuse, and like theirs his aim was a modern synthesis of Marx and Freud. Habermas accepted that the social conditions that obtained when Marx was alive have changed markedly and that, for example, the working class long ago became ‘integrated into capitalist society, and is no longer a revolutionary force.’49 Anthony Giddens has drawn attention to the fact that Habermas shared with Adorno the view that Soviet society was a ‘deformed’ version of a socialist society. There are, Habermas said, two things wrong with regarding the study of human social life as a science on a par with the natural sciences. In the first place there is a tendency in modern intellectual culture to overestimate the role of science ‘as the only valid kind of knowledge that we can have about either the natural or the social world.’50 Second, science ‘produces a mistaken view of what human beings are like as capable, reasoning actors who know a great deal about why they act as they do.’ There cannot be ‘iron laws’ about people, says Habermas, criticising Marx as much as natural scientists. Otherwise there would be no such thing as humans. Instead, he says, humans have self-reflection or reflexivity, intentions and reasons for what they do. No amount of natural science can ever explain this. His more original point was that knowledge, for him, is emancipatory: ‘The more human beings understand about the springs of their own behaviour, and the social institutions in which that behaviour is involved, the more they are likely to be able to escape from constraints to which previously they were subject.’51 A classic case of this, says Habermas, occurs in psychoanalysis. The task of the analyst is to interpret the feelings of the patient, and when this is successful, the patient gains a greater measure of rational control over his or her behaviour – meanings and intentions change, entities that cannot be represented by the natural sciences.52 He envisages an emancipated society in which all individuals control their own destinies ‘through a heightened understanding of the circumstances in which they live.’53 In fact, says Habermas, there is no single mould into which all knowledge can fit. Instead it takes three different forms – and here he produced his famous three-part argument, summed up in the following table which I have taken from Giddens:54

The ‘hard sciences’ occupy the top row, activities like psychoanalysis and philosophy occupy the middle row, and critical theory, which we can now see really includes all the thinkers of this chapter, occupies the bottom row. As Foucault, Derrida, and the others would all agree, the understanding of the link between knowledge and power is the most emancipatory level of thinking.

What the French thinkers (and Habermas) produced was essentially a postmodern form of Marxism. Some of the authors seem reluctant to abandon Marx, others are keen to update him, but no one seems willing to jettison him entirely. It is not so much his economic determinism or class-based motivations that are retained as his idea of ‘false consciousness,’ expressed through the idea that knowledge, and reason, must always be forged or mediated by the power relations of any society – that knowledge, hermeneutics, and understanding always serve a purpose. Just as Kant said there is no pure reason, so, we are told from the Continent, there is no pure knowledge, and understanding this is emancipatory. While it would not be true to say that these writers are anti-scientific (Piaget, Foucault, and Habermas in particular are too well-informed to be so crude), there is among them a feeling that science is by no means the only form of knowledge worth having, that it is seriously inadequate to explain much, if not most, of what we know. These authors do not exactly ignore evolution, but they show little awareness of how their theories fit – or do not fit – into the proliferation of genetic and ethological studies. It is also noticeable that almost all of them accept, and enlist as support, evidence from psychoanalysis. There is, for anglophone readers, something rather unreal about this late continental focus on Freud, as many critics have pointed out. Finally, there is also a feeling that Foucault, Lacan, and Derrida have done little more than elevate small-scale observations, the undoubted misuses of criminals or the insane in the past, or in Lacan’s case vagaries in the use of language, into entire edifices of philosophy. Ultimately, the answer here must lie in how convincing others find their arguments. None has found universal acceptance.

At the same time, the ways in which they have subverted the idea that there is a general canon, or one way of looking at man, and telling his story, has undoubtedly had an effect. If nothing else, they have introduced a scepticism that Eliot and Trilling would have approved. In 1969, in a special issue of Yale French Studies, structuralism crossed the Atlantic. Postmodernist thought had a big influence on philosophy in America, as we shall see.

Roland Barthes is generally considered a poststructuralist critic. Born in 1915 in Cherbourg, the son of a naval lieutenant, he grew up with a lung illness that made his childhood painful and solitary. This made him unfit for service in World War II, during which he began his career as a literature teacher. A homosexual, Barthes suffered the early death of a lover (from TB), and the amount of illness in his life even led him to begin work on a medical degree. But during his time in the sanatorium, when he did a lot of reading, he became interested in Marxism and for a time was on the edge of Sartre’s milieu. After the war he took up appointments in both Bucharest (then of course a Marxist country) and Alexandria in Egypt. He returned to a job in the cultural affairs section of the French Foreign Office. The enforced solitude, and the travel to very different countries, meant that Barthes added to his interest in literature a fascination with language, which was to make his name. Beginning in 1953, Barthes embarked on a series of short books, essays mainly, that drew attention to language in a way that gradually grew in influence until, by the 1970s, it was the prevailing orthodoxy in literary studies.55

The Barthes phenomenon was partly a result of the late arrival of Freudianism into France, as represented by Lacan. There was also a sense in which Barthes was a French equivalent of Raymond Williams in Cambridge. Barthes’s argument was that there was more to modern culture than met the eye, that modern men and women were surrounded by all manner of signs and symbols that told them as much about the modern world as traditional writing forms. In Mythologies (1957, but not translated into English until 1972), Barthes focused his gaze on specific aspects of the contemporary world, and it was his choice of subject, as much as the content of his short essays, that attracted attention.56 He was in essence pointing to certain aspects of contemporary culture and saying that we should not just let these phenomena pass us by without inspection or reflection. For example, he had one essay on margarine, another on steak and chips, another on soap powders and detergents. He was after the ‘capillary meanings’ of these phenomena. This is how he began his essay ‘Plastic’: ‘Despite having names of Greek shepherds (Polystyrene, Polyvinyl, Polyethylene), plastic, the products of which have just been gathered in an exhibition, is in essence the stuff of alchemy … as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible … it is less a thing than the trace of a movement…. But the price to be paid for this success is that plastic, sublimated as movement, hardly exists as a substance…. In the hierarchy of the major poetic substances, it figures as a disgraced material, lost between the effusiveness of rubber and the flat hardness of metal…. What best reveals it for what it is is the sound it gives, at once hollow and flat; its noise is its undoing, as are its colours, for it seems capable of retaining only the most chemical-looking ones. Of yellow, red and green, it keeps only the aggressive quality.’57

Barthes’s Marxism gave him, like Sartre, a hatred of the bourgeoisie, and his very success in the analysis of the signs and symbols of everyday modern life (semiology, as it came to be called) turned him against the scientific stance of the structuralists. Fortified by Lacan’s ideas about the unconscious, Barthes came down firmly on the side of humanistic interpretation, of literature, film, music. His most celebrated essay was ‘The Death of the Author,’ published in 1968, though again not translated into English until the 1970s.58 This echoed the so-called New Criticism, in the 1940s in America in particular, where the dominant idea was ‘the intentional fallacy.’ As refined by Barthes, this view holds that the intentions of an author of a text do not matter in interpreting that text. We all read a new piece of work having read a whole range of works earlier on, which have given words particular meanings that differ subtly from one person to another. An author, therefore, simply cannot predict what meaning his work will have for others. In The Pleasures of the Text (1975), Barthes wrote, ‘On the stage of the text, no footlights: there is not, behind the text, someone active (the writer) and out front someone passive (the reader); there is not a subject and an object.’59 ‘The pleasure of the text is that moment when my body pursues its own ideas.’60 Like Raymond Wilhams, Barthes was aware that all writing, all creation, is bound by the cultural context of its production, and he wanted to help people break out of those constraints, so that reading, far from being a passive act, could be more active and, in the end, more enjoyable. He was given a rather bad press in the Anglo-Saxon countries, although he became very influential nonetheless. At this distance, his views seem less exceptional than they did.* But he was such a vivid writer, with a gift for phrasemaking and acute observation, that he cannot be dismissed so easily by Anglo-Saxons.61 He wanted to show the possibilities within language, so that it would be liberating rather than constricting. A particularly good example of this would occur a few years later, when Susan Sontag explored the metaphors of illness, in particular cancer and AIDS.

Among the systems of signs and symbols that Barthes drew attention to, a special place was reserved for film (Garbo, Eisenstein, Mankiewicz’s Julius Caesar), and here there was an irony, an important one. For the first three decades after World War II, Hollywood was actually not as important as it is now: the most interesting creative innovations were going on elsewhere – and they were structural. Second, and herein lies another irony, the European film business, and the French film industry in particular, which was the most creative of all, was building the idea of the director (rather than the writer, or the actor or the cameraman) as author.

Hollywood went through several changes after the war. Box-office earnings for 1946, the first full year of peace, were the highest in U.S. film history and, allowing for inflation, may be a record that still stands. But then Hollywood’s fortunes started to wane; attendances shrank steadily, so that in the decade between 1946 and 1957, 4,000 cinemas closed. One reason was changing lifestyles, with more people moving to the suburbs, and the arrival of television. There was a revival in the 1960s, as Hollywood adjusted to TV, but it was not long-lived, and between 1962 and 1969 five of the eight major studios changed hands, losing some $500 million (more than $4 billion now) in the process. Hollywood recovered throughout the 1970s, and a new generation of ‘movie brat’ directors led the industry forward. They owed a great deal to the idea of the film director as auteur, which matured in Europe.

The idea itself had been around, of course, since the beginning of movies. But it was the French, in the immediate postwar period, who revived it and popularised it, publicising the battle between various critics as to who should take preeminence in being credited with the success of a film – the screenwriter or the director. In 1951 Jacques Doniol-Valcroze founded the monthly magazine Cahiers du cinéma, which followed the line that films ‘belonged’ to their directors.62 Among the critics who aired their views in Cahiers were Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, and François Truffaut. In a famous article Truffaut distinguished between ‘stager’ films, in which the director merely ‘stages’ a movie, written by a screenwriter, and proper auteurs, whom he identified as Jean Renoir, Robert Bresson, Jean Cocteau, Jacques Tati and Max Ophüls. This French emphasis on the auteur helped lead to the golden age of the art cinema, which occupied the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s.

Robert Bresson’s early postwar films had a religious, or spiritual, quality, but he turned pessimistic as he grew older, focusing on the everyday problems of young people.63 Une Femme douce (A gentle Woman, 1969) is an allegory: a film about a simple woman who commits suicide without explanation. Her grief-stricken husband recalls their life together, its ups and downs, his late realisation of how much he loves her. Don’t let life go by default, Bresson is saying, catch it before it’s too late. Le Diable probablement (The Devil Probably, 1977) is one of Bresson’s most minimal films. Again the main character commits suicide, but the ‘star’ of this film is Bresson’s technique, the mystery and unease with which he invests the film, and which cause the viewer to come away questioning his/her own life.

The stumbling career of Jacques Tati bears some resemblance to that of his character Mr Hulot: he went bankrupt and lost control of his film prints.64 Tad’s films included Holiday (1949) and Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), but his best known are Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967). Mr. Hulot returns to the screen in the earlier of the two, again played by Tati himself, an ungainly soul who staggers through life in his raincoat and umbrella. In this manner he happens upon the family of his sister and brother-in-law, whose house is full of gadgets. Tati wrings joke after joke from these so-called labour-saving devices, which in fact only delay the forward movement, and enjoyment, of life.65 Hulot forms a friendship with his nephew, Gerald, a sensitive boy who is quite out of sympathy with all that is going on around him. Tati’s innovativeness is shown in the unusual shots, where sometimes more than one gag is going on at the same time, and his clever staging. In one famous scene, Hulot’s in-laws walk back and forth in front of their round bedroom windows in such a way as to make us think that the house itself is rolling its eyes. Playtime (1967) was as innovative as anything Tati or Bresson had done. There is no main character in the film, and hardly any plot. Like Mon Oncle it is a satire on the shiny steel and gadgetry of the modern world. In a typical Tati scene, many visual elements are introduced, but they are not at all obvious – the viewer has to work at noticing them. But, once you learn to look, you see – and what Tati is seeing is the ordinary world around us, plotless, which we must incorporate into our own understanding. The parallel with Barthes, and Derrida, is intentional. It is also more fun.

The new wave or ‘Left Bank’ directors in France all derived from the influence of Cahiers du cinéma, itself reflecting the youth culture that flourished as a result of the baby boom. There was also a maturing of film culture: beginning in the late 1950s, international film festivals, with the emphasis on the international, proliferated: San Francisco and London, in 1957; Moscow two years later; Adelaide and New York in 1963; Chicago and Panama in 1965; Brisbane a year after that; San Antonio, Texas, and Shiraz, Iran, in 1967. Cannes, the French mother of them all, had begun in 1939. Abandoned when Hitler invaded Poland, it was resumed in 1946.

The new wave directors were characterised by their technical innovations brought about chiefly by lighter cameras which allowed greater variety in shots – more unusual close-ups, unexpected angles, long sequences from far away. But their main achievement was a new directness, a sense of immediacy that was almost documentary in its feel. This golden age was responsible for such classics as Les Quatre Cents Coups (Truffaut, 1959), Hiroshima mon amour (Alain Resnais, 1959), A bout de souffle (Godard, 1960), Zazie dans le métro (Louis Malle, 1960), L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Resnais, 1961), Jules et Jim (Truffaut, 1962), Cléo de 5 à 7 (Agnès Varda, 1962), La Peau douce (Truffaut, 1964), Bande à part (Godard, 1964), Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1964), Alphaville (Godard, 1965), Fahrenheit 451 (Truffaut, 1966), Deux ou Trois Choses que je sais d’elle (Godard, 1967), Ma nuit chez Maud (Eric Rohmer, 1967), La Nuit américaine (Truffaut, 1973, translated into English as Day for Night).66

Most famous of the technical innovations was Truffaut’s ‘jump-cut,’ removing frames from the middle of sequences to create a jarring effect that indicated the passage of time (a short time in particular) but also emphasised a change in emotion. There was a widespread use of the freeze frame, most notably in the final scene of Les Quatre Cents Coups, where the boy, at the edge of the sea, turns to face the audience. This often left the ending of a film open in a way that, combined with the nervous quality introduced by the jump-cuts, sometimes caused these films to be labelled ‘existentialist’ or ‘deconstructionist,’ leaving the audience to make what it could of what the director had offered.67 The ideas of Sartre and the other existentialists certainly did influence the writers at Cahiers, as did la longue durée notions of Braudel, seen especially in Bresson’s work. In return, this free reading introduced by the nouvelle vague stimulated Roland Barthes’s celebrated thoughts about the death of the author.68

The film guides say that Hiroshima mon amour is as important to film history as Citizen Kane. As with all great films, Hiroshima is a seamless combination of story and form. Based on a script by Marguerite Duras, the film explores a two-day love affair in Hiroshima between a married French actress and a married Japanese architect. With Hiroshima so closely associated with death, the woman cannot help but recall an earlier affair which she had with a young German soldier whom she had loved during the occupation of France, and who had been killed on the day her town was liberated. For loving the enemy she had been imprisoned in a cellar by her family, and ostracised. In Hiroshima she relives the pain at the same time that she loves the architect. The combination of tender, deliquescent lovemaking and brutal war footage matched her mood exactly.69

Les Quatre Cents Coups is generally regarded as the best film ever made about youth. It was the first of a series of five films, culminating in Love on the Run (1979). ‘The Four Hundred Blows’ (a French expression for getting up to no good, doing things to excess, derived from a more literal meaning as the most punishment anyone can bear) tells the story of Antoine Doinel at age twelve. Left alone by his parents, he gets into trouble, runs away, and is finally consigned to an observation centre for delinquents. Truffaut’s point is that Antoine is neither very bad nor very good, simply a child, swept this way and that by forces he doesn’t understand. The film is intended to show a freedom – geographical, intellectual, artistic – that the boy glimpses but only half realises is there before it is all swept away. Never really happy at school (we are shown others who are unthinkingly happy), the boy enters adulthood already tainted. The famous freeze-frame that ends the film is usually described as ambiguous, but Les Quatre Cents Coups is without doubt a sad film about what might have been.70

A bout de souffle (Breathless) has been described as the film equivalent of Le Sacre du printemps or Ulysses; Godard’s first masterpiece, it changed everything in film. Ostensibly about the final days of a petty (but dangerous) criminal, who initiates a manhunt after he guns down a policeman, the film follows the movements of a man (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo) who models himself on Bogart and the characters he has often seen in Hollywood B gangster movies.71 He meets and falls in love with an American student (Jean Seberg), whose limited French underlines his own circumscribed world and personality. Their very different views on life, discussed in the pauses between frantic action, gave the film a depth that sets it apart from the B movies it both reveres and derides. Michel Poiccard, the Belmondo character, knows only too well the failures of life that Antoine Doinel is just waking up to. It too is about what might have been.72

L’Année dernière à Marienbad, directed by Alain Resnais, scripted by Alain Robbe-Grillet, is a sort of nouveau roman on screen. It concerns the attempts by X to convince A that they met last year in Marienbad, a resort hotel, where she promised (or may have promised) to run away with him this year. We never know whether the earlier meeting ever took place, whether A is ambiguous because her husband is near, or even whether the ‘recollections’ of X are in fact premonitions set in the future. That this plot seems improbable when written down isn’t the point; the point is that Resnais, with the aid of some superb settings, beautifully shot, keeps the audience puzzled but interested all the way through. The most famous shot takes place in the huge formal garden, where the figures cast shadows but the towering bushes do not.73

Jules et Jim is ‘a shrine to lovers who have known obsession and been destroyed by it,’ a story about two friends, writers, and the woman they meet, who first has a child by one of them and then falls in love with the other.74 Considered Truffaut’s masterpiece, it is also Jeanne Moreau’s triumph, playing Catherine. She is so convincing as the wilful third member of the friendship that when she drives into the Seine because Jules and Jim have not included her in a discussion of a Strindberg play, it seems entirely natural.

Deux ou Trois Choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know about Her) was described by the critic James Pallot as ‘arguably the greatest film made by arguably the most important director to emerge since World War II.’75 The plot is not strong, and not especially original: it features a housewife who works part-time as a prostitute. It is a notoriously difficult film, dense with images, with endless references to Marx, Wittgenstein, Braudel, structuralism, all related to film, how we watch film, and – a theme underlying all Godard’s and Truffaut’s work – the place of film in how we lead our lives. Two or Three Things I Know about Her is also regarded as a ‘Barthian film,’ creating and reflecting on ‘mythologies’ of the world, using signs in old and new ways, to show how they influence our thought and behavior.76 This was an important ingredient of the French film renaissance, that it was willing to be associated with other areas of contemporary thought, that it saw itself as part of that collective activity: the fact that Godard’s masterpiece was so difficult meant that he put intellectual content first, entertainment value second. And that was the point. In the third quarter of the century, so far as film was concerned, traditional Hollywood values took a back seat.

In 1980 Peter Brook’s Centre International de Créations Théâtricales, in

Paris, was given the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award. It was no more than he deserved. In many ways, Brook’s relation to theatre was analogous to Boulez’s in music. Each was very much his own man, who ploughed his own creative furrow, very international in outlook, very experimental. In the CICT Brook brought a ‘research’ element to theatre, much as Boulez was doing at IRCAM in music.77

Born in London in 1925, to parents of Russian descent, Brook left school at sixteen and, in wartime, worked briefly for the Crown Film Unit, before being persuaded by his parents that a university education would, after all, be desirable. At Magdalen College, Oxford, he began directing plays, after which he transferred to Birmingham Repertory Company (‘Birmingham Rep’). In an age before television, this was a very popular form of theatre, almost unknown now: new productions were mounted every two weeks or so, a mix of new plays and classics, so that repertory companies with a stable of familiar actors played an important part in intellectual life, especially in provincial cities outside London. When the Royal Shakespeare Company was formed in 1961 in Stratford-upon-Avon and Brook was invited to take part, he became much better known. At Birmingham he introduced Arthur Miller and Jean Anouilh to Britain, and coaxed classic Shakespearean performances out of John Gielgud (Measure for Measure) and Laurence Olivier (Titus Andronicus).78 But it was his sparse rendering of King Lear, with Paul Scofield in the title role, in 1962 that is generally regarded as the turning point in his career. Peter Hall, who helped found both the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre in Britain, asked Brook to join him, and Brook made it a condition of his employment that he could have ‘an independent unit of research.’

Brook and his colleagues spent part of 1965 behind locked doors, and when they presented the fruits of their experiments to the public, they called their performances the ‘Theatre of Cruelty,’ as homage to Antonin Artaud.79 Cruelty was used in a special sense here: Brook himself once said, in his Manifesto for the Sixties, ‘We need to look to Shakespeare. Everything remarkable in Brecht, Beckett, Artaud is in Shakespeare. For an idea to stick, it is not enough to state it: it must be burnt into our memories. Hamlet is such an idea.’80

The most celebrated production in the ‘Theatre of Cruelty’ season was Brook’s direction of Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade. The full title of the play explains the plot: The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade. Weiss himself described the play as Marxist, but this was not especially important for Brook. Instead he concentrated on the intensity of experience that can be conveyed in theatre (one of Brook’s aims, as he admitted, was in helping the theatre to overcome the onslaught of television, which was the medium’s driving force in the middle years of the century). For Brook the greatest technique for adding intensity in the theatre is the use of verse, in particular Shakespeare’s verse, which helps actors, directors, and audience concentrate on what is important. But he realised that a twentieth-century technique was also needed, and for him the invention was Brecht’s, ‘what has been uncouthly labelled “alienation.” Alienation is the art of placing an action at a distance so that it can be judged objectively and so that it can be seen in relation to the world – or rather, worlds – around it.’ Marat/Sade showed Brook’s technique at work. When they began rehearsals, he asked the actors to improvise madness. This resulted in such cliché-ridden eye-rolling and frothing at the mouth that he took the company off to a mental hospital to see for themselves. ‘As a result, I received for the first time the true shocks that come from direct contact with the physically atrocious conditions of inmates in mental hospitals, in geriatric wards, and, subsequently, in prisons – images of real life for which pictures on film are no substitute. Crime, madness, political violence were there, tapping on the window, pushing open the door. There is no way. It was not enough to remain in the second room, on the other side of the threshold. A different involvement was needed.’81

It was after another Shakespearean success, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, at the RSC in 1970 (and after he had directed a number of productions in France), that Brook was offered the financial assistance he needed to set up the Centre International de Recherche Théâtrale (CIRT), which later became CICT. Brook’s aim in doing this was to move away from the constraints of the commercial theatre, which he regarded as a compromise on what he wanted to do.82 Brook attracted actors from all over the world, interested as he was not only in acting but in the production and reception of theatre and in ways in which research might add to the intensity of the experience.

Orghast (1971) was a recasting of the Prometheus myth, performed at Persepolis and written in a new language devised by the British poet tell Hughes (who was appointed poet laureate in 1984). This play in particular explored the way the delivery of the lines – many of which were sung in incantation – affected their reception. Hughes was also using the ideas of Noam Chomsky, and the deep structure of language, in the new forms he invented.83

Moving into the abandoned Bouffes du Nord theatre, built in 1874 but empty since 1952, Brook embarked on an ambitious – unparalleled – experiment, which had two strands. One was to use theatre in an attempt to find a common, global language, by peopling his productions with actors from different traditions – South American, Japanese, European – but also by exposing these experimental productions to audiences of different traditions, to see how they were received and understood. This meant that Brook tackled some improbable ideas – for example, Conference of the Birds (1979), based on a twelfth-century Sufi poem, a comic but painful allegory about a group of birds that sets off on a perilous journey in search of a legendary bird, the Simourg, their hidden king.84 Of course, the journey becomes a stripping away of each bird’s/person’s façades and defences, which Brook used as a basis for improvisation. A second improbable production was The Mahabharata (1985), the Sanskrit epic poem, fifteen times the length of the Bible. This six-hour production, which reduces the epic to the ‘core narrative’ of two warring families, was researched in India, which Brook referred to fondly in his memoirs: ‘Perhaps India is the last place where every period of history can coexist, where the ugliness of neon lighting can illuminate ceremonies that have not changed in ritual form nor in outer clothing since the origin of the Hindu faith.’85 He took his leading actors to India to spend time in holy places, so that they might at least half-appreciate the Vedic world they were about to portray. (The various versions of the script took ten years to pare down.) The third of Brook’s great non-Western innovations was The Ik, a play about famine in Africa. This looked back to the books of the anthropologist Colin Turnbull, who had discovered a series of extraordinary tribes around the world, and forward to the economics of Amartya Sen, the Indian who would win the Nobel Prize in 1998 for his theories, expressed throughout the 1980s, about the way famines developed. To complement these non-Western ideas, Brook also took his company on three great tours – to Iran, to Africa, and to the United States, not simply to entertain and inform but also to study the reaction to his productions of the audiences in these very different places. The tours were intended as a test for Brook’s ideas about a global language for theatre, and to see how the company might evolve if it wasn’t driven by commercial constraints.86

But Peter Brook was not only experimental, and not only French-oriented – he thought theatre in Britain ‘very vital.’87 The CICT continued to produce Shakespeare and Chekhov, and he himself produced several mainstream films and opera: Lord of the Flies (1963), based on William Golding’s novel about a group of young boys marooned on a desert island, who soon ‘return’ to savagery; Meetings with Remarkable Men (1979), based on the spiritualist George Ivanovich Gurdjieff’s autobiography; and La Tragédie de Carmen (1983). He also produced a seminal book on the theatre, in which he described four categories of theatrical experience – deadly, holy, rough, and immediate. At the end of his memoirs, Brook said that ‘at its origin, theatre was an act of healing, of healing the city. According to the action of fundamental, entropie forces, no city can avoid an inevitable process of fragmentation. But when the population assembles together in a special place under special conditions to partake in a mystery, the scattered limbs are drawn together, and a momentary healing reunites the larger body, in which each member, re-membered, finds it place … Hunger, violence, gratuitous cruelty, rape, crime – these are constant companions in the present time. Theatre can penetrate into the darkest zones of terror and despair for one reason only: to be able to affirm, neither before nor after but at the very same moment, that light is present in darkness. Progress may have become an empty concept, but evolution is not, and although evolution can take millions of years, the theatre can free us from this time frame.’88

Later on, Brook made a play from Oliver Sacks’s book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, describing a number of neurological oddities. And that surely underlines Brook’s great significance in the postwar world. His attempts to go beyond the narrow confines of nationality, to discover the humanity in science, to use scientific techniques in the production of great art, show an unusual vision on his part as to where the healing in modern society is necessary.89 Brook, though he himself might eschew the term, is also an existentialist. To return to his memoirs: ‘I have witnessed no miracles, but I have seen that remarkable men and women do exist, remarkable because of the degree to which they have worked on themselves in their lives.’90 That applies exactly to Peter Brook. In particular, and perhaps uniquely, he showed how it was possible to bestride both the francophone and anglophone culture of his time.