“Most Everything I’ve Done I Copied from Somebody Else”

—Sam Walton1

As we’ve already seen, Starbucks is a “copycat” company, a fusion of an Italian café with a McDonald’s-style operating system.

There’s nothing wrong with that: most successful businesses are copycats. They’re based on the idea that people are much the same the world over. So if people in one part of the world—say, Italy—like sitting around drinking espressos, so will people in another part of the world. Say, the United States.

Or to go one step farther—as Starbucks has proved, with stores in seventy-three countries and counting—everywhere.

CLUE #2

The Copycat Principle

Starbucks, Ray Kroc’s McDonald’s, Walmart, and Whole Foods are all copycats. None of them were pioneers in their product and market niche; they all took existing practices from their competitors—and perfected them.

So are most of the other recent success stories; Internet Explorer copied Netscape. In turn Explorer was copied by Firefox and Google. Samsung copied the iPhone—wherever you look, you’ll find copycats.

And being a first mover can be a disadvantage. Netscape, Burger King, FedMart, Myspace, and Peet’s are just a handful of many such examples.

The genesis of both Starbucks and McDonald’s lay in the founder’s epiphany: an “Aha!” moment that brought the vision of the business into the founder’s mind almost fully formed.

Howard Schultz and Ray Kroc had both the experience to recognize the opportunity and the talents to turn their vision into a reality.

Sam Walton and John Mackey, the founders of Walmart and Whole Foods, had those same talents and experience. But the development of the underlying concepts of these businesses, and their equivalent “Aha!” moments, came more slowly. The slowest of all, Sam Walton’s concept for Walmart.

Aside from a stint in the army during World War II, Sam Walton spent his life in the retail business, starting as a management trainee in a JCPenney department store in June 1940.

After the war, he bought a Ben Franklin variety—or five-and-dime—store in Newport, Arkansas. Across the street was another five-and-dime, a Sterling store with twice the sales of his Ben Franklin.

Walton haunted the aisles of the Sterling store to figure out what they were doing that he wasn’t.

Which is how much of Walton’s, and Walmart’s, success began—with his continual study of what other retailers were doing. Wherever he traveled, he visited retail stores—including, his children recalled, while on vacation. He carried a yellow legal pad (later, a tape recorder as well) and made notes of anything and everything that struck him as a potentially useful idea.

He went to trade association meetings where he picked the brains of other retailers. He visited store owners in other states, who were happy to answer his many questions, as he was not (then) a competitor.

He returned from every trip with one or more new merchandising, pricing, display, or store-design concepts to try out in his own stores.

He would test each idea in a small and cheap way, discarding it if it failed and rolling it out if it succeeded.

Walton turned copycatting into a fine art. His Ben Franklin store soon caught up with and then outsold the Sterling store on the other side of the street.

But one store wasn’t enough. By 1960, Walton had grown into the biggest independent store operator in the United States. But “we were doing only $1.4 million [total sales] in fifteen different stores,”2 most of them Ben Franklins.

He began looking around for something to take him into the next league.

The concept for Walmart developed from a number of sources, including:

• larger stores—then called family centers—which outsold the combined volume of his fifteen stores in a single location; and

• discount chains such as Ann & Hope in New England and FedMart in California, which made up for lower prices with higher volumes.

Walmart was also a reactive move on Walton’s part. Only when Dallas-based discounter Herb Gibson opened a discount store in Fayetteville, Arkansas, which competed directly with Walton’s variety stores, was he spurred into action.

When the first Walmart in Rogers, Arkansas, opened on 2 July 1962, it was the laggard of the industry.

It was not the first discount store in the state, let alone the country; it was in no sense a dramatically new idea (even the name, Walmart, was a clone of Sol Price’s FedMart); and Kmart and Target had beaten Walton to the punch by four and two months, respectively.

No 1962 observer of the retail trade had Walmart on his list of Retailers Most Likely to Succeed.

So how did Walmart come from behind, if not from last place, to become the world’s number one?

Take the Concept to the Extreme

One reason: with stores in small towns in Arkansas—America’s boondocks—nobody noticed them. Walton could hone his concept while flying under everyone’s radar. Even when Walmart went public in 1970, nobody considered it a serious competitor to the then much bigger Kmart and Target chains.

Far more important, Walton took his focus on low prices to an extreme. He insisted on a maximum 30 percent markup compared to other discounters’ up to 50 percent.

To offer the lowest prices and make a profit, he had to have the lowest costs. A major aspect of the resulting Walmart culture is best expressed in Walton’s statement to his buyers: “Every time Walmart spends one dollar foolishly, it comes right out of our customers’ pockets. Every time we save them a dollar, that puts us one more step ahead of the competition—which is where we always plan to be.”

Walmart has received a lot of flak for allegedly paying its workers less or giving them fewer benefits than its competitors. But that’s all part of Walmart’s overriding aim: to give every customer the best possible deal by having the lowest-possible costs, across the board.

Costco: Even More Extreme

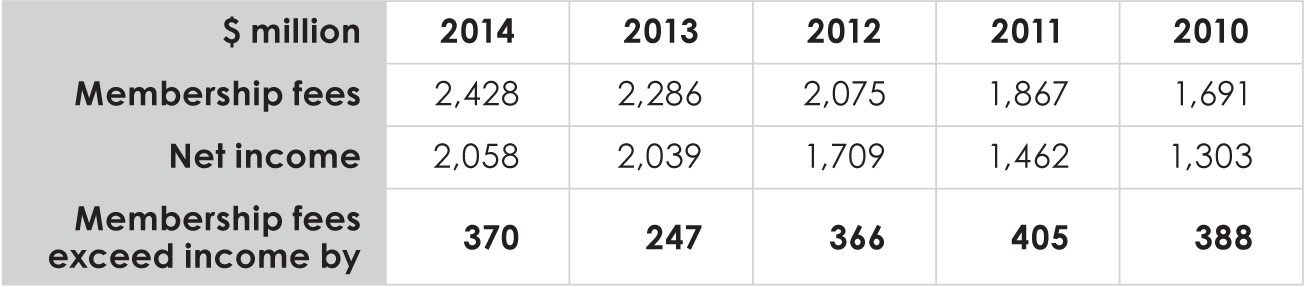

Costco’s markups are even lower than Walmart’s: just 14 percent.3 Customers make up the difference with membership fees. As you can see from this extract from Costco’s financials, without membership fees the company would suffer a loss:

Source: Costco 2014 Annual Report4

“I Have Never Seen Anything to Equal the Potential of This Place of Yours”

—Ray Kroc to the McDonald Brothers5

For seventeen years, Ray Kroc sold paper cups for the Lily-Tulip Cup Company, becoming their star salesman, selling 5 million paper cups a year.

In 1938 he quit Lily-Tulip to start a totally new business selling MultiMixers, which made five milk shakes at a time.

Kroc visited thousands of restaurants, soda fountains, dairy bars, and other kitchens across the United States. For most of these customers, one MultiMixer, occasionally two, was more than enough.

But in 1954, he heard of a restaurant in San Bernardino, California, called McDonald’s that had not two, not three, but eight of his MultiMixers—and had just ordered two more. This was something he had to see.

He visited the store on his next trip to Los Angeles—and was astounded. It was a drive-in restaurant and didn’t look impressive—until opening time. Customers parked, ordered from windows, and took their purchases back to their cars. There was no seating. Yet, within minutes of the store’s 11:00 a.m. opening, the parking lot was nearly full, and long, but fast-moving lines of eager customers were at the windows.

Kroc could see immediately why they needed eight of his MultiMixers: they had to make up to forty milk shakes at a time to keep up with demand.

Kroc was impressed with everything he heard and saw. When he went to bed that evening “visions of McDonald’s restaurants dotting crossroads all over the country paraded through my brain,”6 each, of course, with eight of his Multi-Mixers churning out forty shakes at a time.

At dinner with the McDonald brothers the following evening, he said to them:

“I have never seen anything to equal the potential of this place of yours. Why don’t you open a series of units like this? It would be a gold mine for you and for me, too, because every one would boost my MultiMixer sales. What do you say?”

Silence.

The brothers weren’t interested.

“It would be a lot of trouble,” Dick McDonald objected. “Who could we get to open them for us?”

I sat there feeling a sense of certitude begin to envelop me. Then I leaned forward and said: “Well, what about me?”7

Kroc was then fifty-two years old, an age when most people are looking forward to retirement. He suffered from diabetes and arthritis, had no gallbladder and not much of his thyroid gland. He returned to Chicago, mulled it over for a week—and returned a week later to sign a franchise deal.

By 1972, McDonald’s, with 2,155 stores, was the world’s number one hamburger chain, a position it has retained, without interruption, to the present day.

Burger King

Ray Kroc was not the only person directly inspired by the McDonald brothers.

In 1953—the year before Ray Kroc’s visit—two men from Jacksonville, Florida, Keith Kramer and Matthew Burns, visited the McDonald brothers’ original store.

When they returned home, they opened their own copycat named Burger King (initially Insta-Burger King). It was purchased by its Miami franchisees in 1961.8

The Virtues of Being a Copycat

Being a copycat rather than a pioneer has many virtues. To start with, you know the concept works. You don’t need to prove that; only whether you can make it work in your market.

It’s Easier to Raise Capital

The true pioneer must persuade investors that he has the skills, talents, and management team to produce this totally new, untried, and unproven idea at a profit—and that consumers will love it so much it will fly off the shelves. Easy enough to do in periods such as the dot-com boom of the late nineties; not so easy when investors are more rational.

The founder of a copycat company only has to convince investors that he can make money with a proven concept.

You Can Benefit from the Pioneers’ Experience

One virtue of being a follower is that you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. You can (and should) learn from other people’s successes and mistakes,* just as Sam Walton did for his entire professional life.

Or, like Ray Kroc, you can take a proven operating system and duplicate it worldwide—with, in Kroc’s case, starting further along the learning curve by not having to repeat all the McDonald brothers’ mistakes.

Or, like Howard Schultz and John Mackey, a combination of both.

You Can Start with a Clean Slate

Any company that’s been operating for a while establishes a particular way of doing business. Such an institutional legacy—especially when it develops on a catch-as-catch-can basis—can be resistant to change, a perilous attitude in a changing market and when the competition heats up.

With sufficient thought and experiment, you can establish your company’s culture and style from day one so that every part of the business meshes with your vision for the company and its primary purpose.