How Ray Kroc’s McDonald’s Trumped Burger King with Superior Entrepreneurial Management and Execution

In 1948, brothers Richard “Dick” and Maurice “Mac” McDonald opened a drive-in restaurant in San Bernardino, California, simply named McDonald’s, that was destined to revolutionize the world’s food business.

Not that that was the McDonald brothers’ intention. They lived on a hill overlooking their restaurant and spent a lot of their spare time sitting on the veranda “watching the store.” Like Canberra’s Augustin Petersilka—who fought city hall and won so he could have his café his way—they were pioneering innovators in restaurant operations. They had no interest in expanding, unlike Howard Schultz, John Mackey, Sam Walton, and Ray Kroc, who are pioneering innovators in business management.

But the McDonald brothers were (of course!) happy to take “free money” from visitors who marveled at their operation—initially, a series of neighboring Californians to whom they sold individual franchises; eventually, entrepreneurs who did have Schultz-like ambitions:

• Keith J. Kramer and Matthew Burns, who, inspired by what they saw, opened their own copycat, Insta-Burger King, in Jacksonville, Florida, on 28 July 1953.

• James McLamore and David R. Edgerton, who—inspired by the Jacksonville copycat of the McDonald brothers’ store—became the Miami, Florida, franchisee for Insta-Burger King (quickly renamed Burger King). Their first store opened in Miami on 1 March 1954—and they bought control of the Jacksonville franchisor in 1961.

• Ray Kroc, who franchised McDonald’s and grew it from one store in Des Plaines, Illinois (opened on 15 April 1955), to 34,492 worldwide today.1

Today, McDonald’s is the world’s number one hamburger (and, by sales, restaurant) chain, while Burger King, despite its head start, remains a distant number two.

Along the way, however, another hamburger chain you’ve probably never heard of almost trumped McDonald’s: Burger Chef. In 1971 it was less than a hundred restaurants shy of McDonald’s almost thirteen hundred—and way ahead of Burger King, which had some eight hundred stores. Burger Chef was adding a new location every forty-eight hours, so it was within shouting distance of wresting the number one slot away from the then-much-slower-growing McDonald’s.

But in 1982, shrunken to under half its 1971 size, what was left of Burger Chef was taken over by Hardee’s and disappeared from the “hamburger wars.” Meanwhile, Burger King’s growth almost ground to a halt—leaving the field wide open for McDonald’s.

The different fates of these three hamburger chains illustrate the overwhelming significance of the fifth clue: superb entrepreneurial management and execution.

CLUE #5

Superb Entrepreneurial Management and Execution

Without entrepreneurs at the helm who also have superb management and execution skills, the presence of the previous four clues in a company may signal a profitable and viable operation, but not one that could be the next Starbucks, Whole Foods, Walmart, or McDonald’s.

White Castle: Creating America’s First National Food

Until Walt Anderson and Billy Ingram opened their first White Castle restaurant in Wichita, Kansas, in 1921, products made with ground beef were widely viewed as being unsafe to eat.

White Castle’s featured product was a square hamburger, known as a slider, just over half the size of a McDonald’s burger, sold for a nickel.

A White Castle restaurant in New York today.

Thanks to White Castle’s success, copycats sprang up almost instantly, with “innovative” names such as White Crescent, White Knight, Blue Castle, Royal Castle, Red Barn, Red Lantern, and Klover Kastle.

The affordability of the slider, and White Castle’s and its clones’ emphasis on pristine cleanliness, changed the unsafe-to-eat perception of the hamburger. So much so that by the advent of World War II, the hamburger was firmly established as America’s first truly national food.

Ironically, though White Castle paved the way for the rapid postwar expansion of McDonald’s, Burger King, Burger Chef, Hardee’s, Jack in the Box, and other burger chains, in a fate common to most first movers, it didn’t benefit itself.

Though White Castle still exists, selling its signature slider, by spurning the franchise model in favor of company-owned stores, it has, today, just 421 locations.

How McDonald’s Automated the Food Business—and Created “Fast Food”

In 1937, the McDonald brothers opened a carhop in San Bernardino, California. Carhops, restaurants where you were served in your car, grew rapidly in popularity in the United States during the interwar period, spurred by the dramatic increase in automobile ownership.

Analyzing their business, the brothers discovered that hamburgers were their biggest-selling item, accounting for 80 percent of their sales.

So in 1948 they closed the carhop and replaced it with the world’s first self-service, limited-no-choice-menu, fast-food restaurant, slashing the necessary investment in inventory.

They completely redesigned their food-production methods, introducing automation on a scale never before seen in the restaurant business.

They called their new method the Speedee Service System.

By investing capital in production methods, they dramatically lowered their costs. Their new McDonald’s was a self-service restaurant, eliminating the twenty-plus carhop waiters on roller skates who served customers in their cars.

The machinery they designed, made by a local craftsman, meant they could hire unskilled labor instead of qualified cooks. Most restaurants prepared one meal at a time. By adapting Henry Ford’s production-line techniques to food preparation, with just twelve employees—three to cook the burgers, two making milk shakes, two for french fries, two who assembled the burgers, and three men who worked the counter—they could easily serve more than one customer every minute.

The restaurant design was also innovative: their new octagonal store was essentially a kitchen enclosed by glass. Customers could see the food being prepared—and, more important, see that the kitchen was kept spotlessly clean, an important selling point.

Selling tenth-of-a-pound hamburgers for 15¢—half the 30¢ charged elsewhere, along with french fries (added in their second year of operation), milk shakes, and soft drinks, the brothers’ new store was an almost-instant success. Though profitable from the start, it was a year before their strange new restaurant’s profits exceeded the carhop’s … and kept growing.

Enter the Copycats

Their concept was so innovative it was soon written up in the trade press and attracted a flood of interest, visitors—and copycats.

In 1953, two of those visitors were Keith Kramer and Matthew Burns, who left San Bernardino inspired to create their own McDonald’s clone in their hometown of Jacksonville, Florida.

While in California, they met George Read, who’d invented Insta machines that—like the McDonald brothers’ innovations—automated the production of hamburgers and milk shakes. Kramer and Burns signed a franchise giving them exclusive use of Read’s Insta-Burger and Insta-Shake machines in the state of Florida.

As Kramer and Burns were building their first Insta-Burger store in Jacksonville, they received a visitor: David Edgerton, a former manager of a Howard Johnson restaurant in Miami.

Attracted by the high margins, he was planning to open a Dairy Queen franchise in the Miami area. But when he saw the Insta-Burger store in Jacksonville, he changed direction. Edgerton’s Insta-Burger store opened in Miami on 1 March 1954—renamed, at Edgerton’s urging, Insta-Burger King.

But his first store got off to a rocky start. Needing capital, Edgerton persuaded James McLamore to join him: on 1 June 1954, they became fifty-fifty partners in Burger King of Miami Inc.

McLamore was also an experienced restaurant operator—and entrepreneur.

He had learned the restaurant business as the director of food service at the YMCA in Wilmington, Delaware. At a mere twenty-one years of age, he revamped the operation so thoroughly it made more money in his first year at the helm than it had in the previous thirty years combined.2

Two years later he opened the Colonial Inn, a White Castle copycat.

In February 1951, McLamore visited Miami and was impressed by the number of restaurants offering shoddy service and indifferent food—all with long lines of customers patiently waiting to get a table.

Confident he could do much better, McLamore opened a restaurant and put the Colonial Inn up for sale.

His new venture, the Brickell Bridge Restaurant, was a disaster.

As he candidly admitted many years later,3 his decision was an impetuous mistake. Aside from choosing a poor location, he soon discovered, to his consternation, that February’s apparent restaurant boom was seasonal. By May, most of those restaurants had shut their doors for the summer and stayed shut till the “snowbirds” returned the following winter.

Searching for a way to fill his almost-empty tables, he hired a twelve-year-old kid named Charlie to walk back and forth in front of his restaurant, wearing a chef’s hat and ringing a bell, inviting passersby to come on in.

“Dinner Bell Charlie” attracted a flood of curiosity seekers—but not too many new customers.

McLamore’s Impetuous Decisions

One of McLamore’s management flaws was a tendency to make impetuous decisions that failed to pay off. This, as we’ll see in the following pages, was a major factor that enabled McDonald’s to pull ahead of Burger King.

Which is not to say that Ray Kroc and others never made such impetuous mistakes. Indeed, Kroc’s agreement with the McDonald brothers falls into that same category.

The difference between Kroc and McLamore—a difference essential to growing a business that can become the next Starbucks—is that whenever Kroc recognized he’d made such a mistake, he was willing to pay the price to correct it, even when he couldn’t afford it.

Kroc, unlike McLamore, always “went the extra mile.”

Only when McLamore ran newspaper ads in which Dinner Bell Charlie invited people to a prime sirloin steak dinner for just $1.95 (McLamore’s cost) did the Brickell Bridge Restaurant become popular—so popular it had lines of customers waiting outside even during the slow summer months.

McLamore described this marketing idea—the combination of a unique personality for the business with a low price—as “one of the great learning experiences”4 of his life. A learning experience that would turn Burger King around after several years of far more downs than ups.

How the Whopper Saved Burger King

The Miami market for burgers was owned by Royal Castle, a White Castle copycat, thanks to its sponsorship of Miami’s number one children’s show.

McLamore and Edgerton’s strategy was to scale up stores so they, too, could afford to advertise. But with four money-losing stores, it wasn’t working.

In 1956 McLamore met a retired businessman, Harry Fruehauf, who invested $65,000 for 50 percent of the company and became a mentor to McLamore and Edgerton.

Fruehauf’s capital injection enabled Burger King to add three more stores, which also lost money.

In early 1957, McLamore and Edgerton visited Gainesville, Florida, to see a new Burger King that Kramer and Burns had just opened. It had no customers!

Just a hundred yards down the street was another hamburger store—with a long line of people waiting patiently outside. McLamore wandered over to see what the attraction was.

The restaurant was a ramshackle mess: dirty and dusty from the unpaved parking lot, poorly fitted out, with indifferent service—the opposite of the new and empty Burger King store a short walk away.

McLamore joined the slow-moving line to discover that the lure was a quarter-pound hamburger served on a five-inch bun. What’s more, he saw some customers come out with bags full of these burgers.

After he bought one for himself and one for Edgerton, a couple of bites proved that the burger was worth the wait.

On the drive back to Miami, unable to get that hamburger out of his mind, McLamore suggested they introduce a copycat burger in their restaurants, call it the Whopper, and change their signage from BURGER KING to BURGER KING: HOME OF THE WHOPPER. Edgerton immediately agreed.

Just a few days later, the Whopper was on sale at all their restaurants.

At 39¢, including tax, it was “a stunning success from the moment it was introduced.”5

The red ink at their seven money-losing restaurants soon turned black.

Now, McLamore was in his element. With the highly marketable Whopper backed up by new machines that didn’t break down and a redesigned operating and ordering system that customers hardly noticed, Burger King began to expand rapidly … in South Florida. But not even the Whopper could save Kramer and Burns’s northern-Florida operation.

Burger Chef: “The Greatest Might-Have-Been in the History of the Fast Food Business”6

Burger Chef had its origin in a prototype store created by an Indianapolis company named General Equipment Inc., a manufacturer of machines for the restaurant trade. The purpose: to showcase their products to potential customers in a real-time environment.

Opened in 1957,7 the demonstration store, called Burger Chef, quickly filled with local customers who preferred the quality and value of the food produced by the company’s machines to that offered by other Indianapolis restaurants.

It also attracted a different kind of interest: entrepreneurs looking for a turnkey franchise operation. The management soon decided to franchise their restaurant concept, partly on the basis—like Ray Kroc and his MultiMixer—that “it might be a great way to sell more equipment.”8

General Equipment was founded by an inventor and entrepreneur, Frank Porter Thomas, who cut his teeth in the amusement-park industry. In 1926 he built the world’s first “fun house” ride near Indianapolis. Thanks to its popularity, he was commissioned to build similar rides in New Jersey, Boston, Rhode Island, and Ohio.

Flush with cash, in 1929 he began construction of his own park, which opened in Corpus Christi, Texas, on 4 July 1930.

His timing, in the early months of the Great Depression, could hardly have been worse; it was a disaster.

Thomas returned to Indianapolis broke—down, but not out. A restaurant called the North Pole was serving a new dish: frozen custard. Thomas saw the custard machine and figured he could do better. When he brought his new prototype to the North Pole, the owner promptly bought Thomas’s machine and junked the one he’d been using.

Other restaurant owners had similar reactions, and soon Thomas had customers for his EZE-Way frozen-custard maker all over the United States and Canada.

In 1946, Thomas retired, turning the business over to his sons, Frank Porter Thomas Jr., an inventor in his own right, who became president, and Don Thomas, who was in charge of engineering.

That same year, a salesman from California whose customers were feeling the heat from the fast-expanding Dairy Queen chain called to ask, Could they provide a machine that made a similar soft-serve ice cream?

They could and they did. Sales of their new SaniServe, as it was called, mushroomed so fast that in 1950 they had to build a new factory to meet demand.

In 1952, the company added a third product, a modification of the SaniServe, called the SaniShake, which produced a fully completed milk shake with one turn of a spigot, and was a competitor to Ray Kroc’s MultiMixer.

In 1956 Frank Jr. was approached by Burger King’s Dave Edgerton, who wanted to know if General Equipment would be interested in manufacturing his improved version of the Burger King’s flunky Insta-Broiler machine.

The Thomas brothers reengineered and dramatically improved Edgerton’s design. With their Sani-Broiler, far superior to the Insta-Broiler, General Equipment now produced an almost-complete lineup of the machines needed to set up a hamburger restaurant, which led to the demonstration store in 1957, and the franchising of Burger Chef a year later.

Burger Chef, in other words, was inspired by Burger King—and McDonald’s. “Without that phone call [from Dave Edgerton],” Frank Thomas Jr. relates, “we would never have made a broiler, and Burger Chef would never have existed.”9

When they decided to franchise Burger Chef, they cloned McDonald’s method of operation.

Burger Chef’s Advantages over McDonald’s

Though started three years after Ray Kroc opened his first McDonald’s, Burger Chef had several advantages.

1. It was backed by a profitable operation, while Ray Kroc started McDonald’s on a shoestring. And it was run by a management team that had already proved its entrepreneurial credentials.

2. Burger Chef wasn’t hamstrung by any arrangements like Kroc’s deal with the McDonald brothers (or McLamore and Edgerton’s restrictive franchise).

3. Through the serendipity of their prototype store, they had discovered a concept that was highly marketable.

4. Finally, they benefited from the experience—and learned from the mistakes—of Ray Kroc and the many other restaurant franchises that were mushrooming across the United States in the early 1950s.

One spin-off advantage was that they could—and did—invest considerable time, effort, and money in planning the franchising operation before signing up franchisees. Kroc, McLamore, and Edgerton learned the business on the fly; by taking the time to study what worked (and what didn’t) from their competitors, Burger Chef opened for business much further down the learning curve.

In other words, like Starbucks, Whole Foods, Walmart, and McDonald’s itself, Burger Chef had all the advantages of the second clue, the copycat principle, of not being the first—or, indeed, even the second—mover in the hamburger wars.

So had we been applying these principles back in the late 1950s and early ’60s, we might well have picked Burger Chef over McDonald’s as the hamburger chain that was going to dominate the market.

What’s more, Burger Chef almost did!

The first Burger Chef (not counting the prototype store) opened in Indianapolis on 3 May 1958, followed by two more by year’s end.

At that time, McDonald’s had been in business for three years and had seventy-nine outlets. McLamore and Edgerton had been in business four years and had seven stores.

Burger Chef quickly overtook Burger King with 681 stores by 1967,10 compared to McDonald’s 857, while Burger King was closing in on 300. From a standing start, Burger Chef had become the fastest-growing restaurant chain in the United States and was second, by sales, only to McDonald’s.

All three chains were growing fast. Even Burger King, though coming from behind, was adding stores almost as fast as McDonald’s. The enormous potential for expansion meant that even Burger King had a realistic opportunity of winning the “hamburger wars.” But then …

McDonald’s Changes the Rules

On 21 April 1965 McDonald’s went public and changed the rules of the game. As a listed company, it could now access the bond market and borrow money on more favorable terms than still-private Burger Chef and Burger King and could use its stock as currency.

At that time all three chains could open a new store confident it would be profitable. Just one limitation held back their rate of new-store development: capital. Capital that Burger King and Burger Chef managements felt was now available to McDonald’s in relative abundance.

Both managements succumbed to the pressure to seek their own capital injection, afraid that otherwise McDonald’s would leave them in the dust.

Little did they know that as a result of its going public, McDonald’s expansion rate was about to slow down.

And paradoxically, by succumbing to the fear of being outfinanced, both managements acted in haste, exposing their internal management flaws.

As a result of finding new money, all three companies entered a crisis: one chain disappearing; one simply halting dead in its tracks; while the third almost broke in half.

In each case, their fates were self-inflicted, dramatizing the significance of superb entrepreneurial management and the consequences of its lack. And, at the same time, the difference between entrepreneurial management and corporate management.

Ray Kroc: Always Going the Extra Mile

The obstacles confronting Ray Kroc’s McDonald’s were formidable.

To begin with, he was tied hand and foot by the franchise agreement he’d personally negotiated with the McDonald brothers. What he’d thought was a great deal turned into a nightmare that drove him crazy. As he put it later, “A man who represents himself has a fool for a lawyer.”11

His problems began immediately.

The agreement required him to copy the brothers’ San Bernardino store in every excruciating detail. But Kroc’s architect’s first questions about the plan for his first store in Des Plaines, Illinois, were “Where are you going to put the basement? And the furnace?”

The desert design had to be adapted for Illinois’s alternately freezing and hot and humid climate.

But any deviation from the San Bernardino model had to be agreed to by both brothers in a signed letter sent by registered mail. The brothers said “go ahead” over the phone—but refused to send the necessary letter.

While planning his first store Kroc discovered, by accident, another, far more serious problem. On a sales call to the Frejlich Ice Cream Company to sell them MultiMixers, he mentioned his deal with the McDonald brothers. Only then did he learn that the Frejlich brothers had bought an exclusive franchise for four McDonald’s stores in Cook County just before Kroc signed his agreement.

Cook County was Kroc’s home turf, including not only Chicago but also Des Plaines, where he planned to open his first, prototype store!

The brothers had told him of ten other franchises they’d sold in California and Arizona, but neglected to mention the eleventh one, in the Chicago area.

The Frejlich brothers were happy to bank a quick profit, asking $25,000 for their $10,000 purchase. Kroc (after he’d calmed down) persuaded the McDonald brothers to refund the Frejliches’ $10,000, but where to find the rest?

Soggy French Fries

Another major problem for Kroc: the french fries in his Des Plaines store were soggy, far below the standard set by the McDonald brothers.

It took Kroc a year of intense research to find the reason: desert air.

The McDonald brothers stored their potatoes in a warehouse behind their restaurant. Open to the dry desert air—but protected from rats and other vermin by wire mesh—the low humidity reduced the potatoes’ water content, making a dramatic difference to their taste when cooked.

Duplicating that desert air in Chicago’s alternately humid or freezing environment required developing special drying equipment, housed in the basement. More major variations from the San Bernardino model that the brothers agreed to—only over the phone.

Such continual refusals to put anything in writing meant Kroc was in violation of the agreement from the get-go—a shaky foundation for his business.

He offered a 50 percent interest in his franchising company for $20,000, an investment that would eventually be worth billions. But there were no takers. Ultimately, he arranged a bank loan for the balance.

This action was typical of Ray Kroc. When he faced a problem, he attacked it mercilessly, moving heaven and earth until he’d solved it, paying the necessary price even when he couldn’t afford it.

This was just the first of several such seemingly impossible obstacles that Kroc overcame by frontal assault.

Ray Kroc always went the extra mile.

But paying the necessary price to buy out the Frejlich brothers left him with another, equally serious problem. He was not just stretched but also totally starved for capital.

Why Not “Kroc’s” Instead of “McDonald’s”?

You may be wondering why Kroc didn’t simply walk away from the agreement and do what others had done: set up their own McDonald’s clone without paying the brothers a dime?

He certainly considered that option. But Kroc’s approach to business was that of a salesman. That was his strength—but also his weakness.

He felt that McDonald’s was a marketable name while Kroc’s (rhyming with crock) was not. He could have chosen another name, but the McDonald’s system was a complete product, one he knew he could sell. And he would benefit from tapping the brothers’ expertise and years of experience. Experience he did not have.

With a salesman’s optimism, he was also confident he could renegotiate the registered-letter requirement in the agreement. That optimism was totally misplaced. When he later met with the brothers and their lawyer, they were immovable and intransigent.

Kroc’s first McDonald’s opened in Des Plaines on 15 April 1955 with encouraging—and profitable—first-day sales of $366.12. That may not sound like a lot today, but it works out to 2,440 sales at an average product price of 15¢. Or about a thousand customers.

Kroc hoped his demonstration store would attract potential franchisees. But it didn’t. The hamburger business in the Chicago area then was mostly owner-operators running a stand, and they were only open for the seven warmest months of the year.

But one person the store did attract that same year was Harry Sonneborn.

Sonneborn had just resigned his position as vice president of Tastee-Freez after a disagreement with its founder, Harry Axene.

In 1944, Axene formed a partnership with the founder of Dairy Queen, then with just eight stores. Axene sold territorial franchises for $25,000 to $50,000 apiece, for whole cities or states. When he resigned in 1948, Dairy Queen had twenty-five hundred stores across the United States, a dramatic success that spurred dozens of restaurant-franchising copycats including Big Boy burgers, Chicken Delight, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Taco Bell.

In 1950 Axene started Tastee-Freez, a Dairy Queen clone, with fifteen hundred stores when Sonneborn resigned.

Sonneborn visited the Des Plaines McDonald’s store, and as he later told Kroc, “I can tell just by watching it from across the street that you have a winner there.”12 And he wanted to work for Kroc.

Kroc was in a financial bind. He had just one employee, his secretary and assistant, June Martino. His only income—indeed, after buying out the Frejliches, his only source of capital—was from Prince Castle and its MultiMixer sales.

As Kroc later admitted, he’d been supremely confident that profits would automatically follow sales. He also knew his finances were a mess, but the subject barely interested him. Logical (perhaps) for a salesman, but potential suicide for a businessman.

When he met with Sonneborn, Kroc knew he was just the financial man Kroc needed. But he couldn’t afford to hire him—while at the same time he couldn’t afford not to.

That dilemma was resolved when Sonneborn came back with an offer to work for just enough to cover his keep: $100 a week. A quarter of what he’d been earning at Tastee-Freez.

Kroc and Sonneborn were a study in opposites. Kroc was an extrovert, a “people person” who loved to sell one-on-one, focused on selling hamburgers. Sonneborn, an introvert, had no interest in hamburgers. He didn’t even like them. Indeed, he couldn’t care less whether a business was selling hamburgers, burritos, widgets, or whatever. What attracted him to McDonald’s was not hamburgers but the fact that they were flying out the door.

Kroc knew that. But an excellent judge of character, he also knew that Sonneborn would put twenty-four hours a day into McDonald’s, just as Kroc did.

Kroc’s employment style was extreme delegation. Sonneborn took charge of finances and financing, and Kroc left him to it.

He soon proved his worth.

Starved for Capital

Kroc’s agreement with the McDonald brothers required him to charge no more than $950 for a franchise, and a fee of 1.9 percent of sales, 0.5 percent of which went to the brothers. This was a great deal for the franchisees—and a recipe for disaster for Kroc. Every new franchise sale was cash-flow negative up front, while 1.4 percent of sales barely covered the cost of servicing franchisees.

Kroc also made a fundamental decision to spurn the industry practice of manufacturing or sourcing supplies and equipment and requiring franchisees to purchase them from the franchisor. With the one exception of MultiMixers, which did not turn out to be the cornucopia Kroc had expected. Most McDonald’s franchisees needed just two, not the ten the McDonald brothers had.

In the long run this turned out to be an excellent decision. In the short to medium run it meant that Kroc’s only source of revenue was the insufficient franchising fees. In the five years leading up to 1960, McDonald’s sales totaled $75 million while its earnings were a minuscule $159,000.13 Kroc didn’t even draw a salary until 1961.

So where to find the capital to expand? Franchising was the obvious solution: get someone else to put up the money.

As the original home of McDonald’s, with a climate where drive-in restaurants flourished twelve months of the year, California was a logical place for expansion. Nine of the eighteen franchises Kroc sold in his first year were in California.

But from two thousand miles away in Chicago it was impossible for Kroc to effectively monitor the maverick California operators. They all went their own way, diverting from the McDonald’s system by charging different prices and by adding various other menu items from hot dogs to burritos and pizza. Fred Turner later termed it “fast-food anarchy.”

In Illinois, Kroc turned to his friends at his golf club. They’d initially thought he was crazy to go into the 15¢ hamburger business. Some of them changed their minds when they saw the profits of the Des Plaines store.

But they were absentee investors, indifferent to Kroc’s operational standards so long as they banked a profit. So Kroc had no more success enforcing his high standards on them than he’d had in California.

Then, one day Betty Agate walked into the office of Kroc’s assistant, June Martino—to sell Bibles. Instead, Martino sold her and her husband on the idea of having their own McDonald’s store.

Betty Agate and her husband, Sandy, were owner-operators, the opposite of Kroc’s golf-club friends. They invested everything they had into their restaurant, and both worked behind the counter.

Their store opened on 26 May 1955 in Waukegan, Illinois, fifty miles north of Chicago, a working-class town like San Bernardino, and did a land-office business. In their first year, the Agates grossed $250,000 and took home $50,000 in profits. With numbers like that, it became the showcase for anyone interested in taking on a McDonald’s franchise.

How Harry Sonneborn Turned McDonald’s into a Money Machine

Stores such as the Agates’ were financed by third parties. Kroc, Sonneborn, or the franchisee found a banker or a landlord willing to build the store and lease it to the franchisee.

Harry Sonneborn institutionalized this model. Instead of the franchisee leasing the premises direct, McDonald’s, initially, leased the store and subleased it to the franchisee.

Later, Sonneborn refined the model, buying the land and building the store. A new franchisee was required to put down a rental deposit equal to the amount McDonald’s needed for the down payment to purchase the land. McDonald’s required the seller to take part of his or her payment in a note, classed as a second mortgage, so McDonald’s was able to then take out a first mortgage from a bank with the land as security, so providing the money to buy the land and build the store.

McDonald’s then rented the finished store to the franchisee at a minimum monthly figure that included a 20 percent to 40 percent markup over the payments McDonald’s had to make to repay the bank and the seller—or a percentage of sales, usually 8.5 percent, whichever was greater.

Provided the store was profitable, it was a no-risk arrangement—which ended up with McDonald’s owning the real estate at zero cost!

This brilliant solution provided the necessary capital for McDonald’s expansion—and as an unexpected side effect, eventually made McDonald’s the most profitable, by a long shot, of the three competing chains.

Furthermore, as part of the lease agreement, the franchisee was required to meet Kroc’s operational standards. This gave Kroc sufficient control over franchisees’ operations to ensure a far superior uniformity in the customer experience across all McDonald’s stores than any of its competitors could achieve in their stores.

In 1960, Sonneborn took this model to the next level by negotiating a loan of $1.5 million from two insurance companies. As part of the agreement, McDonald’s created a subsidiary, Financial Realty Inc., to house all the real estate—and give the lenders additional security.

But to close the deal, McDonald’s had to part with 22.5 percent of the company’s equity. Both Kroc and Sonneborn vowed they’d never repeat this incentive.

Exit the McDonald Brothers

The following year, conflicts between Kroc and the McDonald brothers came to a head. Kroc decided he had to buy them out. They were agreeable—for $2.7 million, which would give each of them $1 million after tax.

Once more, money Kroc didn’t have.

McDonald’s net worth was a mere $250,000. Aside from the $1.5 million it had just borrowed, McDonald’s was up to its eyeballs in real estate debt, and the more stores McDonald’s opened, the more leveraged it became. Its balance sheet was enough to give any banker a heart attack.

Nevertheless, Harry Sonneborn came up with yet another creative financing arrangement. One that was expensive in the short run, but turned out to be a masterstroke several years later.

McDonald’s borrowed $2.7 million from a consortium of twelve trust funds, including those of Princeton University, Howard University, and Swarthmore College.

The interest rate on the loan was an about-market 6 percent—exceptionally reasonable given that McDonald’s then had a close-to-zero (if not negative) credit rating.

Further, loan repayments were set at 0.5 percent of McDonald’s systemwide sales. The beauty of this arrangement was that it cost McDonald’s nothing—since it was committed to paying out that 0.5 percent of its 1.9 percent share of franchisees’ sales anyway. The money just went to the lenders instead of the McDonald brothers.

Thanks to Sonneborn, this agreement actually improved McDonald’s cash flow. While 0.5 percent of sales were due, the lenders agreed that McDonald’s could hold back 0.1 percent, which would be paid at the end of the loan period.

Now free of the McDonald brothers’ restraints, Kroc could increase his rate of expansion and, more important, increase franchisees’ fees and charges.

But there was a kicker (in case you’re wondering whether the lenders had lost their minds): when the loan was paid back in full, McDonald’s had to continue the same 0.5 percent payments for the same period. So if repayment took ten years, the lenders received payments for twenty years.

The lenders estimated that it would take McDonald’s about fifteen years to repay the loan, and their expected return would be somewhere between $7.1 million and $9 million.

In fact, the loan was repaid in five and a half years. The total cost to McDonald’s: $14 million, a return to the lenders of 518 percent!

Going Public

After the buyout of the brothers and with its real estate financing strategy, McDonald’s was in good financial shape. It didn’t need to tap Wall Street for more money, the usual rationale for going public.

The pressure to list came from a different source.

Kroc had built an impressive management team who had come on board at below-market salaries. Although McDonald’s was profitable, it still wasn’t profitable enough to raise Martino’s and Sonneborn’s (or, for that matter, Kroc’s) salaries.

Unable to increase their pay, Kroc compensated these two key associates with 10 percent and 20 percent of the equity respectively. They, along with Kroc himself, were keen to realize some cash rewards for their efforts; going public was the solution.

So when McDonald’s hit Wall Street on 21 April 1965, the main sellers were Kroc, Martino, and Sonneborn—and the two insurance companies with their 22.5 percent of the equity. Not the company itself.

The 1960s: Go-Go Years on Wall Street

McDonald’s timing was perfect. Its listing on Wall Street hit in the midst of “conglomerate frenzy.” When McDonald’s soared, from $22.50 to $30 on its first day of trading, and more than doubled in the following two weeks, restaurant chains were added to the brew.

In quick succession, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Royal Castle, and Howard Johnson went public, along with two Burger King franchisees, Self Service Restaurants (New Orleans), and Mallory Restaurants (Long Island, New York).

The “Suede Shoe Boys”

With Kentucky Fried Chicken trading at a hundred times earnings, and similar sky-high valuations for other chains, promoters—or, as James McLamore called them, “the suede shoe boys”14—poured into the market.

The most famous of these was Minnie Pearl Fried Chicken.

Advertising itself as the Pepsi of the fried-chicken business, the company sold large territorial franchises to gullible investors. Each franchise gave the buyer the right to a specified number of Minnie Pearl stores in a specific territory. The franchisee was required to put up a small cash deposit, further payments to be made as stores were opened.

The company then booked the entire projected revenue as income!

Minnie Pearl’s stock soared in the same way and for many of the same reasons as the dot-bombs of the late nineties. Listing in 1968, it opened at $20 a share and closed the day at $40. With just $2.2 million in assets and five barely profitable stores, it reached a market cap of $81 million—before going bankrupt (though not before the promoters had pocketed a small fortune). Minnie Pearl was just one of many similar scams based on the accounting fraud of booking projected future income as if it had been received today.

Meanwhile, takeover fever infected company managements nationwide, who, like lemmings, joined the fray—and the latest hot category of fast-food restaurants became an essential addition to their shopping lists. In quick succession, Servomation bought Red Barn, Ralston Purina took over Jack in the Box, PepsiCo scooped up Pizza Hut and Taco Bell, while Marriott picked up Big Boy, and Imasco merged with Hardee’s.

Ramping up Earnings

The sixties was the decade of the conglomerate. “Synergy” was the mantra of the time. By combining a diverse collection of unrelated companies, conglomerates would supposedly benefit from reduced costs; increased buying power; slimmer, more professional management—and so, higher profits. The whole was (supposedly) greater than the parts.

For example, ITT—originally International Telephone and Telegraph—bought over three hundred companies in the “go-go years,” including businesses as unconnected with each other (or telecommunications) as Sheraton Hotels, Continental Baking, Avis Rent a Car, Education Services, and Hartford Insurance Co.

Meanwhile, Ling-Temco-Vought, or LTV, added businesses from missiles to car rentals and golf equipment, while Gulf & Western scooped up hotels, real estate companies, and movie producers, to name just a few.

The theory was synergy, but the reality was mostly financial engineering. Here’s how it worked.

Being in favor, conglomerates traded at high P/E ratios. Using their stock as currency, they could buy companies with low P/Es and boost their stock’s value.

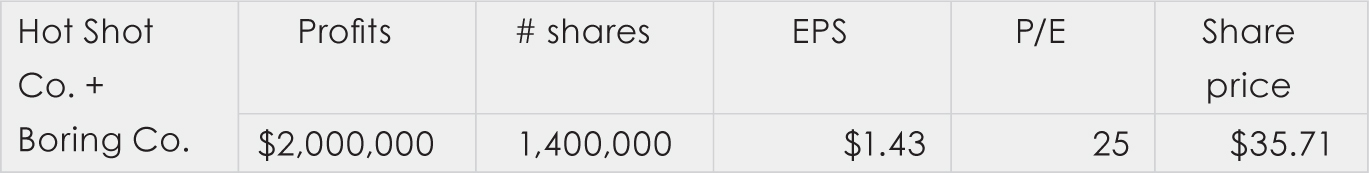

Hot Shot Co. Inc., with a million shares outstanding and reported* profits of a million dollars, is trading at twenty-five times earnings, giving it a per-share value of $25.

Meanwhile, Boring Bricks & Mortar Inc., with the same profits but only four hundred thousand shares, is trading at just ten times earnings—or the same $25 a share.

So Hot Shot Co. issues four hundred thousand new shares to “merge” with Boring Bricks & Mortar, with this result:

Thus a 42.85 percent boost to the share price as Boring Bricks & Mortar’s earnings are “magically” rerated from ten to twenty-five times earnings.

Talk about financial fairy tales!

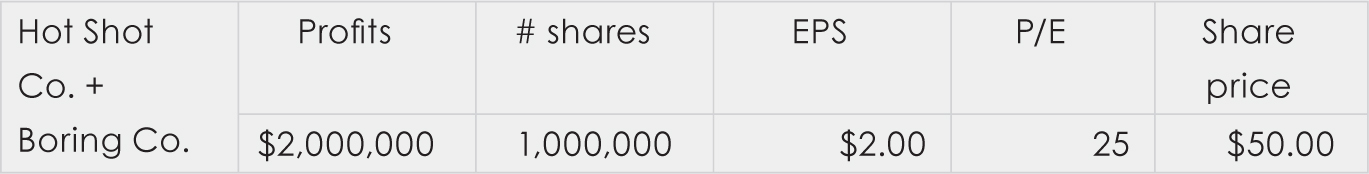

But Hot Shot Co. can do even better if it can borrow the necessary million bucks and simply buy Boring Co.:

A double! True financial wizardry!

In reality, the wizardry was rarely this obvious. The Hot Shot conglomerates of the era usually bought companies much smaller than themselves. The result was the same over time—but in small, incremental bites rather than huge chunks.

*“Reported” profits aren’t necessarily the same as true profits, especially when the stock market is hot. See my post, Cooking the Books—and Screwing the Shareholders (marktier.com/cooking) for a short course in how to do it.

The perfect environment, you’d think, for Burger King and Burger Chef to partake of some of that financial wizardry for themselves.

So why didn’t they both join McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and the flood of other fast-food restaurants in the rush to Wall Street?

Why, instead, did James McLamore and Frank Thomas both decide to sell out to a conglomerate—Burger King to Pillsbury and Burger Chef to General Foods?

Analyzing their decision-making underlines the difference between entrepreneurial management and what we might term the extreme entrepreneurial management of Ray Kroc.

Or to put it a different way:

Why James McLamore and Frank Thomas Didn’t Go the Extra Mile

McLamore and Thomas made their decisions to sell out in 1966 and 1967 respectively. Thanks to President Lyndon Johnson’s policy of guns (for Vietnam) and butter (to keep voters happy and his popularity rating high), inflation and interest rates were heading up. On Wall Street, stocks had crashed. Though it was not officially a recession, a significant consensus in 1966–67 was that that’s where the economy was heading.

That environment ruled out an IPO.

With conglomerate offers on the table, the pressure from feeling they had to have a capital injection to keep up with McDonald’s, and the obvious attraction of cashing in their chips, both McLamore and Thomas made decisions that, in retrospect, were disastrous for both Burger King and Burger Chef.

But those reasons were merely the proximate causes. Underlying those decisions were—from our point of view as entrepreneurs or investors searching for the next Starbucks—deeper flaws in both management teams.

Burger King’s “Split Personality”

Seven problems plagued Burger King from the start. One—fierce competition—was external. The other six, however, were inherent in the way Burger King and its owners operated.

External

1. Fierce competition: The Florida market was dominated by Royal Castle, a White Castle clone, thanks to its sponsorship of Miami’s most popular children’s TV show.

In Chicago, Ray Kroc’s McDonald’s faced scattered competition mainly from other McDonald brothers’ clones. Burger King opened in a market “owned” by a well-established competitor and its 15¢ slider. Considering that White Castle, Red Barn, and Hardee’s, among many other profitable chains flourishing in other parts of the United States, entered the Florida market—and were all forced to withdraw—it’s a wonder that Burger King survived.

Internal

2. “Schizophrenia”: the division between Kramer and Burns in Jacksonville and their South Florida franchisees, Edgerton and McLamore.

Kramer and Burns sold franchises in northern Florida, but provided little support and failed to ensure consistency across different stores.

Compared to their northern-Florida franchisors, the Edgerton-McLamore operation was a class act. All the ideas for improvements came from them:

• Adding King to the original Insta-Burger name.

• Dropping Insta altogether.

• The Whopper, which saved Burger King—north and south—from total failure.

• And, ultimately, dumping the cranky Insta machines entirely.

Even Kramer and Burns turned to Edgerton and McLamore for advice.

This division between the entrepreneurial South Florida franchisees and the lackadaisical northern-Florida franchisors delayed the nationwide expansion of Burger King by almost a decade. Burger King grew and prospered in South Florida, but potential franchisees from other parts of the United States had to deal with Kramer and Burns. One look at the northern-Florida operation was usually enough for the potential franchisees to shake their heads and walk away (probably to McDonald’s!).

3. Trademarks: Kramer and Burns registered the trademarks Burger King and the Whopper.

Edgerton and McLamore were the originators of both names—and Burger King’s slogan, “Home of the Whopper”—but received no credit. What’s more, they did not protest. The result: an asset that should have been 50 percent if not 100 percent theirs eventually cost them $2.55 million to buy back.

4. The Insta-Burger machine was unreliable: It regularly broke down, so the affected store was out of business until it could be fixed or replaced by a backup. As you can imagine, this certainly did nothing to improve the customer experience!

One day, after about two years (!) of suffering with this problem, Dave Edgerton lost his cool when the machine broke down and destroyed it with a hatchet, yelling, “I can build a better machine than this pile of junk.”

“Well, you’d better get busy and build it,” McLamore replied, “because right now we are out of business until we get our only spare machine in operation.”15

Soon thereafter, Edgerton and McLamore announced they were dumping the Insta machines for their own superior replacement (manufactured, paradoxically, by the company that would soon open a McDonald’s/Burger King copycat, Burger Chef!). Kramer and Burns quickly followed suit.

5. Pricing: Burger King’s raison d’être, its hamburger, was priced at 18¢ compared to 15¢ most everywhere else.

Burger King’s 18¢ burger patty was about twice the size (8.9 to the pound) and less than twice the cost of Royal Castle’s 15¢ slider, but to customers it didn’t appear to be a bargain price.

Burger King’s higher price combined with its unreliable Insta machine and a poorly thought-out ordering system turned customers away.

The cumulative result of these problems: all the Burger King stores lost money until the entire operation was rescued by the Whopper.

6. Edgerton and McLamore were slow to resolve these problems: Taking two years to replace the unreliable Insta-Burger machine was typical of Edgerton and McLamore’s slow resolution of the problems that plagued their operations.

Other examples include:

• Opening new money-losing stores in the hope expansion would turn the business around.

• Not willing to pay the price: starved for capital, like most start-ups, Edgerton and McLamore put off solutions to problems when they seemed too expensive.

• Staying with the 18¢ burger.

As James McLamore wrote thirty-four years later, “I believe that one of our biggest mistakes was staying with our higher-priced hamburger rather than offering one that we could design and sell for 15 cents.”16

7. A dysfunctional partnership: The partnership of McLamore, Edgerton, and Harry Fruehauf became dysfunctional at the worst possible moment: when McDonald’s changed the rules by going public.

Raising Capital on a Shoestring

The success of the Whopper had an unexpected side effect that helped alleviate Burger King’s capital shortage: soon after its introduction, Charlie Krebs walked into their office to ask if they’d accept $20,000 for one of their stores.

Until that moment, McLamore and Edgerton had worked on the assumption that all their outlets would be company owned.

Desperate for capital, they quickly agreed. And by 1957, they had sold all their original stores and were busy building new ones—to franchise.

By 1958, McLamore had begun small-scale advertising on radio and TV. His big break came the following year when Royal Castle inexplicably decided to drop its sponsorship of Skipper Chuck’s Popeye Playhouse, the most popular children’s show in the Miami area. Immediately when he heard, McLamore agreed to sponsor the show—even though he had no idea how he would pay for it.

This was one of his few Kroc-like decisions—agree, then figure out how and where to find the money.

His decision paid off: targeting children brought more families into his stores (a strategy that McDonald’s replicated many years later with its Ronald McDonald clown), adding to the bottom line. And Burger King’s increased “presence of mind” in the Miami market brought in more franchisees.

Going Nationwide

At their troubled Jacksonville operation, Kramer and Burns followed Fruehauf’s injection of equity with keen interest and soon decided to follow McLamore and Edgerton’s example. A Jacksonville businessman, Ben Stein, took a 50 percent equity interest in Burger King of Florida and loaned the company a significant sum to finance expansion.

Kramer and Burns quickly added several new stores in the Jacksonville area—with disastrous results. The new stores were all in poor locations and poorly managed to boot. When they defaulted on the loan, Ben Stein assumed control of the company.

Stein, though an astute businessman, was unfamiliar with the restaurant business and was unable to turn the northern-Florida operation around. He turned to McLamore and Edgerton, suggesting they take over his operations, which in 1961—after two years of fruitless, on-off discussions—they did. Stein kept the trademarks in return for 15 percent of the franchise fees.

McLamore and Edgerton could now take Burger King nationwide.

Shortly afterward, McLamore asked Stein at what price would he sell the trademarks. “One hundred thousand dollars” was Stein’s immediate response. An amount McLamore felt he couldn’t afford.

As Burger King expanded, its payments to Stein went up—as did Stein’s buyout price: $100,000 was substantially less than the $2.55 million Stein received in 1967. Had McLamore “gone the extra mile” and come up with $100,000 in 1961, even at outrageous interest rates Burger King would have been substantially better off.

As McLamore later admitted, when Ray Kroc “went the extra mile” by borrowing money he couldn’t afford to buy out the McDonald brothers, he “came up with the better solution.”17

Once McLamore and Edgerton were in the saddle, they no longer had to send potential franchisees to the shabbily run Jacksonville operation. By 1965, they were adding one new Burger King almost every week; two years later that rate had doubled, matching McDonald’s.

A major factor in this growth was selling franchises for whole cities or states. The franchisee agreed to open a certain number of stores on a fixed schedule, which shifted the capital cost from Burger King to the franchisee.

Keeping up with McDonald’s

“We needed capital to stay in the race, and we needed to find it rather quickly”18 was McLamore’s reaction to McDonald’s April 1965 public offering.

Although McLamore was concerned that by diluting his and Edgerton’s share of equity they could lose control, the partners agreed that a public offering was the best option, and Fruehauf introduced McLamore to a Wall Street firm he was familiar with: Blyth and Company.

In early 1965, McLamore and Fruehauf visited New York. Burger King’s numbers were certainly striking: $446,239 in earnings for the year ended 31 May 1965, with $750,000 or more projected for 1966. But Blyth seemed less than impressed.

Soon afterward, McLamore was invited back to New York only to learn that Blyth thought the partners were too young, inexperienced, and undercapitalized for an IPO.

After this discouraging rejection McLamore went straight to the airport to catch a flight back to Miami; the idea of taking Burger King public was dead.

Here’s a key difference between McLamore and Kroc that made all the difference to the future courses of their two companies.

Had Ray Kroc been in McLamore’s shoes—turned down by the first people on Wall Street he met—it’s unlikely he’d have followed in McLamore’s footsteps back to the airport. Kroc would have started knocking on all the other doors along Wall Street until he found a company that would do, or could be persuaded to do, what he wanted.

Much later, McLamore admitted that at the time he understood nothing about Wall Street and the stock market, and he should probably have brought in an experienced adviser “to guide us through the complexities.” Even worse, he later discovered that he’d been talking to the wrong people: Blyth and Company’s specialty was working with institutions and blue-chip companies in the bond market, not underwriting IPOs for entrepreneurial start-ups.

The partners explored other financial options, meeting with a dozen or more financial institutions, and on 14 April 1966, Mass Mutual extended Burger King a long-term loan of $1.5 million. A number of similar financings were under negotiation. Burger King could now, like McDonald’s, build stores to lease to franchisees.

Just two weeks later, Pillsbury indicated a possible interest in buying Burger King.

McLamore was feeling the pinch. His salary hadn’t increased since he joined with Dave Edgerton in 1954. After ten years of inflation, and with his children about to go to college, McLamore was having trouble making ends meet.

He decided the only way he could solve his cash-flow problem was to sell the company to Pillsbury.

This certainly seems like a radical way of solving a $10,000- to $20,000-a-year problem. One has to ask why he, Edgerton, and Fruehauf didn’t sit down together and discuss it.

From reading between the lines of McLamore’s Burger King, I’ve concluded that McLamore’s relationship with Fruehauf, whom he viewed as a mentor, while friendly, was primarily professional. Edgerton was a friend to whom McLamore could pour out his troubles; Fruehauf was not.

Ray Kroc’s “Marriage” Proposal

Burger Chef and Burger King weren’t alone in receiving corporate suitors. In 1968, Nate Cummings, CEO of Consolidated Foods, approached Ray Kroc to delicately suggest a “marriage” between their two companies.

Kroc’s reaction demonstrated his deep-seated desire to remain independent:

“You’ve got a marvelous company, and that is a great compliment. The problem is that we just wouldn’t consider something like that unless we were the surviving company, and I’m afraid that managing a company like yours is just more than we could handle.”*

No way was Kroc going to give up his baby!

*Grinding It Out

Which is why McLamore refrained from taking the obvious course: explaining his financial dilemma to Fruehauf and requesting he agree to a salary increase.

Whatever the case, McLamore first talked about Pillsbury’s offer to Edgerton, who was reluctant to agree, but was persuaded to go along with his partner’s wishes.

Then the two of them talked to Fruehauf, presenting a united front, and Fruehauf, who was, like Edgerton, less than enthralled by the idea, also agreed—with a distinct lack of enthusiasm.

Very expensive mistakes: By rejecting an IPO in 1965, Burger King missed the possibility of listing in early 1966—and achieving similar multiples to Kentucky Fried Chicken. Burger King and Burger Chef managements both decided to sell their companies during the 1966–67 “mini–bear market,” when no other options seemed available. As a result, both missed out on the dramatic boom in franchising chains kicked off by Minnie Pearl’s IPO in May 1968.

But just as the deal with Pillsbury was about to close, Fruehauf angrily complained to McLamore that he’d made a big mistake. An example of how a dysfunctional partnership at the top can lead to serious business blunders.

Fruehauf spoke his mind but took no action to suggest they explore other options, a topic that—like McLamore’s underlying motivation—never came up in their discussions.

In fact, with the Mass Mutual loan in place, and similar loans under negotiation, Burger King didn’t need to go public to keep up with McDonald’s.

So, because the three partners didn’t talk openly with each other, in June 1967 Pillsbury assumed control of Burger King—one more decision that McLamore (along with Edgerton and Fruehauf) ultimately came to regret.

Frank Thomas: A Second-Generation Entrepreneur

Burger Chef’s management was also spooked by McDonald’s new financial strength. So in mid-1967, when Frank Thomas and his team received two suitors, General Foods and Borden Foods, they were all ears.

Like Burger King and McDonald’s, Burger Chef was profitable. But profits were reinvested in expanding the business rather than paying dividends or raising salaries. Like McLamore and Kroc, Thomas and his partners felt that selling stock was the only way they could realize some cash rewards for their efforts.

Given that Wall Street was collapsing at the time, the idea of a public offering wasn’t ever seriously considered.

But Thomas and his partners’ attitude toward their company was different from Kroc’s and McLamore’s.

Kroc and McLamore were both first-generation entrepreneurs. Their companies—their creations—were their babies. Literally. Their emotional attachment to McDonald’s and Burger King respectively were identical to a mother’s connection with her favorite child: her baby never (really) grows up, and she never wants to let him or her go.

As a second-generation entrepreneur, regardless of the pride he had in his creation, Thomas’s attachment to his company was much looser.

In November 1967, after a mere three months of negotiations, Burger Chef accepted General Foods’ takeover offer at a price variously reported as $15 million, $16 million, and $16.3 million.19

Four million dollars less than Pillsbury paid for the smaller Burger King the previous January.

But the appeal of General Foods’ cash was irresistible. Especially given there was no other option at that moment.

But there were other possibilities—if Thomas had been willing to wait for the stock market to recover.

And stock markets always recover … given time.

Given that Burger Chef had a much bigger footprint than Burger King, was the fastest growing of the three chains, and could, with creative financing, have easily left McDonald’s in the dust, in a few years it could have come to market with a far higher valuation than McDonald’s.

Many multiples of $16 million.

On that basis, General Foods walked off with a steal.

What Went Wrong

In retrospect, the mistakes that McLamore, Thomas, and their respective partners made are clear. Even so, sufficient thought and research—which neither management undertook—could easily have shown the folly of a corporate takeover. And also the wisdom of waiting until the economic climate changed to take their companies public.

• Markets turn around. Always. The macro outlook for an IPO in 1966 or 1967 was certainly bleak. It was only a question of time—though an unknowable time—before the market turned up again.

• They jumped off the deep end. Both company managements accepted corporate offers without investigating the possible consequences. A few calls to entrepreneurs who had sold out to conglomerates would have quickly convinced them that promises of independence afterward were a chimera.

• Burger Chef and Burger King were still growing. Their value-proposition market was far from saturated—as all three chains proved by opening new and profitable stores, regardless of the macro economic climate. The question was not whether they could continue to grow, but whether they could keep up with McDonald’s—and if they were willing to wait till the stock market turned around to cash in some of their chips.

• Financing was still available—as the sad irony of Burger King’s $1.5 million loan demonstrated. Such financings were difficult to arrange at the best of times. Meanwhile, both chains could continue their one-store-at-a-time expansion. After all, this was the model that had grown Burger Chef faster than McDonald’s.

• You don’t need control to keep control. McLamore’s fear that he’d lose control of Burger King by listing on Wall Street was misplaced. Certainly, an IPO would have diluted his—and Edgerton’s and Fruehauf’s—share of equity. And as a listed company Burger King could be vulnerable to a takeover. A possibility easily averted had McLamore, Edgerton, and Fruehauf agreed to vote their shares as a bloc. In reality, with just 25 percent to Fruehauf’s 50 percent, McLamore didn’t have voting control. But as the managers in residence, McLamore (with Edgerton) followed the strategy of most CEOs who own a tiny percentage of their company’s equity: keep your shareholders happy.

Entrepreneurial vs. Corporate Management

Unfortunately, neither Pillsbury nor General Foods subscribed to Warren Buffett’s totally hands-off management style. Despite their promises to the contrary, corporate management quickly replaced entrepreneurial management in both chains, with the result that Burger King effectively dropped out of the hamburger race, while Burger Chef disappeared from the scene, leaving McDonald’s with the number one slot by default.

Meanwhile, McDonald’s itself flirted with corporate management, a divisive excursion that all but halted its growth and virtually split the company in two.

But what, exactly, is “entrepreneurial” management?

Why is it the ultimate key to the success of companies such as McDonald’s, Walmart, Starbucks, and Whole Foods?

In what ways does it differ from what we might call corporate management?

And how can corporate management be the kiss of death for a flourishing entrepreneurial company?

How General Foods’ Corporate Management Killed Burger Chef …

In January 1968, General Foods assumed control of Burger Chef, then with 730 restaurants in thirty-nine states. Three years later, this number had increased to almost 1,200, just 100 stores shy of the McDonald’s total. As Burger Chef was opening stores faster than McDonald’s, to the casual observer it appeared it would shortly knock McDonald’s off the number one spot.

But that growth was an illusion.

The key to any retail expansion is to only open stores that will be profitable. Burger Chef had addressed this problem successfully with its innovative strategy of hiring commissioned sales agents to find new locations and franchisees. As the agents received a percentage of the profits of each new restaurant they had a hand in developing, they worked hard “to not only find the right people and locations for new restaurants, but to ensure their success as well.”20

General Foods’ first action was to appoint their own man, George Perry, as the manager of what was now the Burger Chef division. Perry’s first action was to replace Burger Chef’s entire management team.

Only Frank Thomas Jr. remained—as a consultant. A consultant is someone who can be politely listened to—and then ignored. Which was Frank Thomas’s fate.

The new management team quickly fired all the sales agents—many of whom made far more money than the incoming executives—and replaced them with real estate agents, whose only motivation was making a sale, not building a new and profitable store. In one stroke, General Foods lost the expertise that had ensured new Burger Chefs would be moneymakers.

Stores added under General Foods’ management were often in poor locations run by indifferent franchisees.

While the store count rose dramatically, profits didn’t follow the same trend.

Franchisees now reported to newly appointed regional managers, who were often more interested in using Burger Chef—a sideline to General Foods’ main businesses—as a step up to a higher position on the company’s ladder.

Coming from a command-and-control culture, General Foods’ managers were used to dealing with employees; partnership, the essence of successful franchising, was an alien concept. Franchisees weren’t happy when the new managers’ attitude of dictation replaced the entrepreneurial attitude of consultation. General Foods’ subsequent changes didn’t make them any happier.

Burger Chef’s headquarters were moved from Indianapolis to General Foods’ HQ in Tarrytown, New York, while operations stayed in Indianapolis, a change guaranteed to disrupt communication and coordination within the division. Also one that ensured the managers’ focus was on pleasing their Tarrytown peers, not satisfying Burger Chef’s customers and franchisees.

The position of CEO became a revolving door: in just the two years of 1969 and 1970, Burger Chef was run by four different people!

By replacing entrepreneurial managers with corporate executives from the completely different business of selling packaged foods to supermarkets, General Foods simply discarded the accumulated years of knowledge and experience necessary to run a successful franchising operation. One result:

“According to Frank Thomas, the company spent ‘a hell of a lot of money’ trying concepts that had already been tested and discarded in years past.”21

Eventually, General Foods threw in the towel. Relationships with franchisees had totally soured. The revolving door of the executive suite resulted in Burger Chef stores sporting seven different logos—just the most obvious example of the deterioration of the customer experience. By 1982, store numbers had fallen from their 1971 about-to-top-McDonald’s peak to just 679—less than Burger King.

Burger Chef had changed from a profitable, entrepreneurial company into a money-losing corporate millstone. General Foods had taken enormous write-offs; in 1982 it killed Burger Chef by selling the remaining stores to Hardee’s.

… and Pillsbury Turned Burger King into an Also-Ran

On 21 June 1967, Pillsbury assumed control of a company with 208 stores, profits of $758,000, net assets of $1.7 million*—up from the previous year’s $446,239 and $1,056,612 respectively—and a history of producing a 50 percent to 70 percent return on equity.

All driven by an entrepreneurial, partnership culture totally alien to Pillsbury’s top-down management structure.

Of the Pillsbury managers, only president and CEO Paul Gerot, who championed the acquisition, truly understood and appreciated Burger King’s operational methodology.

In a harbinger of things to come, he had to fight opposition from Pillsbury directors who focused on the assets they were buying, not the business. With that thinking, $20 million was clearly far too much to pay for $1.7 million in net worth. They completely ignored that Burger King’s profits were growing between 48 percent and 107 percent per year (and its implications for the future).

Those directors also “knew” that restaurants have a high failure rate—a failure to understand the completely different nature of Burger King’s franchising business from the dubious prospects of a mom-and-pop, single-location restaurant start-up.

Unfortunately for McLamore and Burger King, three months after the merger Gerot retired. The first action of the new CFO, Terrance Hannold, was to impose standard debt-to-equity ratios on the new subsidiary. This immediately put an end to any possibility of following McDonald’s real estate financing model. And it also broke Gerot’s promise that Burger King would remain autonomous for at least its first year under Pillsbury ownership.

McLamore remained in charge of Burger King, so it avoided Burger Chef’s fate. But his focus slowly changed from expanding Burger King as fast as possible to fighting a rearguard action against Pillsbury’s creeping corporate culture. A fight he eventually lost on the principle that he who holds the purse strings conducts the orchestra.

Those changes came slowly, but inexorably:

• 1967: Pillsbury sends in a management consultant who recommends McLamore abandon his entrepreneurial “hands-on” approach and become a corporate “strategist.” Result: Franchisees have reduced contact with top management, and McLamore begins to lose his enthusiasm for the business.

• 1969: Dave Edgerton resigns, unhappy with the creeping corporate culture. Burger King formally ceases to be autonomous.

• 1970–71: Pillsbury management “developed an increasingly negative attitude toward franchising and real estate development,”22 a symptom of Pillsbury’s failure to understand the partnership relationship that’s the backbone of a successful franchising operation.

• 1971: A top management memo dictates that Burger King’s growth can only be financed from earnings; that new stores will be company owned—although franchisees will be allowed but only as a “last resort.”

• 1972: Pillsbury management makes it clear it despises the franchisee model; and McLamore resigns as CEO. Corporate management now reigns supreme at Burger King.

The following table shows what Pillsbury’s creeping corporate management “achieved”:

In 1967, Burger King had a good chance of keeping up with and even overtaking McDonald’s. Pillsbury’s creeping corporate management brought an end to that possibility. Store openings to the 1970 peak of 167 were mostly in the pipeline when Pillsbury assumed control or came from territorial franchisees who had more room to maneuver than Burger King itself.

Ray Kroc, Harry Sonneborn, and the Triumph of Entrepreneurial Management

The fates of Burger Chef and Burger King illustrate the results of corporate management replacing entrepreneurial management.

The reverse distinction—the triumph of entrepreneurial management—is dramatically illustrated by the changes in the McDonald’s executive suite after Kroc moved to California in May 1962 to revitalize West Coast operations.

McDonald’s had expanded successfully in the Midwest and Eastern states, but Kroc was convinced that McDonald’s needed to succeed on the West Coast as well to become truly viable.

A second motivation for his move to California was personal: Kroc had fallen in love. He and his wife-to-be, Joan Smith, decided to live in Los Angeles. But Joan’s conscience would not let her divorce her husband, and she called the marriage off at the last minute.

Kroc moved to Los Angeles anyway and began replicating the Chicago HQ there—known as the MiniMac—confident he could leave McDonald’s east of the Rockies in the hands of his trusted management team. Especially with Fred Turner as operations chief.

But things didn’t work out that way.

Until 1960, McDonald’s had been divided into two companies: McDonald’s System Inc., the parent company, with Kroc in charge of operations; and Franchise Realty Corporation, a subsidiary, run by Harry Sonneborn, where he worked his financial magic. As a codicil to the $1.5 million loan Sonneborn negotiated that same year, the two companies were merged into one: McDonald’s Corporation. Kroc remained chairman, while Sonneborn became president and CEO.

To Kroc, such titles were meaningless.

His management style was extreme delegation: hire the right person for the job and leave him alone to get on with it. Kroc’s McDonald’s became a highly decentralized, freewheeling operation, where anyone could take the initiative to solve a problem or innovate, even if it meant stepping on someone else’s theoretical “turf.”

This entrepreneurial attitude permeated the company.

An excellent judge of character, Kroc rarely hired round pegs for square holes. His inspirational salesmanship, together with the offer of a position with enormous responsibility—responsibility that people could only achieve elsewhere by spending years climbing a corporate ladder—attracted mavericks who were eager to work at the low salaries Kroc could afford to offer.

People such as Harry Sonneborn.

There’s no question Sonneborn was the right person to bring order to McDonald’s finances. Indeed, without Sonneborn’s ability to raise capital for a company that had a close-to-zero credit rating—junk bond status before there were junk bonds—it’s unlikely that McDonald’s would still exist today.

McDonald’s Business: Hamburgers or Real Estate?

While Kroc remained in Chicago, the change in titles was meaningless: the Kroc/Sonneborn division between operations and finance continued as before.

But with Kroc two thousand miles away in California, the dramatic differences between their two characters began to divide the company. A division that nearly tore McDonald’s apart.

To Kroc, McDonald’s was in the business of selling hamburgers. But his focus was not just on hamburgers but the total customer experience. His mantra to implement this aim was QSCV: Quality, Service, Cleanliness, and Value. He wanted every McDonald’s store to offer a quality experience—in both product and service—at an exceptionally good value in a pristine environment.

The quality controls he established, and their continual improvement, set McDonald’s apart from its competition—and transformed the production of beef, potatoes, bakery, and related products across the United States.

Organizationally, however, his primary focus was on the franchisees: he was, he often said, in the business of creating entrepreneurs.

For a franchisor, this attitude is essential to success. Franchisees are independent businesspeople. They may not be entrepreneurs in the usual sense of the word—that is, starting something from nothing—but they are entrepreneurially inclined.

Furthermore, they’re the public face of the company. They are the ones who give every customer a good or a bad experience. Whether they’re happy or not will be reflected in the customer experience they deliver. Treat them like the partners they actually are, and all will be well. Treat them as employees—as happened with Burger Chef—and you create a recipe for disaster.

Kroc went one step farther: he encouraged franchisees to innovate. The majority of the successful products McDonald’s added to its basic menu, from the Big Mac to the Filet-O-Fish, the Egg McMuffin, and the Apple Pie—not to mention the Ronald McDonald character—were all created and tested first by franchisees. Often over Kroc’s objections.

While every new product Kroc himself proposed bombed.

But to Sonneborn, McDonald’s was in the real estate business. Hamburgers were just the means of building a huge real estate portfolio.

And to Boston and Wall Street financiers, McDonald’s cash flow and sales growth might be impressive—but the security of McDonald’s real estate portfolio was something they really understood.

When Kroc decamped to California, especially after McDonald’s 1965 public offering, Sonneborn began “living up” to his title of McDonald’s president and CEO.

His office was remodeled with plush sofas and dark wood paneling. He added layers of management between franchisees and the head office, chains of command, more rules, and more reports. His focus turned from raising money so Kroc could expand to protecting shareholder value from the dangers that accompanied a high debt-to-equity ratio and the like—so satisfying his Wall Street peers.

It was as if he viewed his earlier, highly overleveraged borrowings as the means to arriving at the goal of respectability on Wall Street.

Gaining and keeping that respectability meant, among other things, reducing leverage. So Sonneborn dramatically cut back McDonald’s rate of expansion. His prudent strategy enabled growth to be financed from cash flow instead of debt—but it enraged Kroc.

While the culture of the Chicago headquarters took on the trappings of corporate management, in California Kroc continued his natural entrepreneurial approach, adding stores as fast as he could—ignoring all of Sonneborn’s rules.

Kroc also began innovating with store designs and patio seating. Until then, all McDonald’s stores—like those of most of its competitors—were pure drive-ins. Customers ate their hamburgers in their cars or took them home.

In Chicago and similar cold climates, such stores were lucky if they broke even in winter. Some drive-ins simply shut down until warmer weather returned.

Sonneborn objected to the expense of Kroc’s changes—even though the addition of outdoor seating increased same store sales.

In the short run, Sonneborn’s strategy did reduce leverage—at the long-run cost of far fewer new restaurants with lower average sales and profits.

Kroc was still in charge, though it wasn’t in his nature to confront people or, having given them the authority, overrule their decisions. He and Sonneborn simply stopped talking to each other; all communication went through June Martino. And the company began to divide into Kroc and Sonneborn camps.

This division had other negative effects. The Kroc people in Chicago became increasingly frustrated and dissatisfied, and some of them accepted offers from other chains at much higher salaries—offers similar to those they had rejected before.

Fred Turner was almost one of them.

Turner was the son Ray Kroc never had. They thought the same way and Kroc saw him as his successor. As operations chief he was growing into that role. But he chafed at Sonneborn’s restrictions and couldn’t understand why Kroc didn’t overrule him. Turner was on the verge of accepting one of many far-more-attractive offers he’d been receiving from other chains when Kroc finally took action. Sonneborn resigned, and Kroc promoted Turner to CEO. Turner’s reaction: “Why did you wait so long?”

With Turner in the saddle, Sonneborn’s corporate-style management was swept away, Kroc’s freewheeling entrepreneurial structure was revived, and McDonald’s began expanding faster than even Kroc had thought possible.

Risk vs. the Perception of Risk

On the surface, it would appear that Kroc’s approach was far riskier than Sonneborn’s. It’s certainly true that in its early days McDonald’s lived on the edge of bankruptcy.