“About half of all new establishments survive five years or more and about one-third survive ten years or more,” reports the American Small Business Administration (SBA).1

This is significantly different from the much-touted figures of the up to 95 percent failure rate for small start-ups.

What about failure rates for new franchised outlets?

A lot lower, most people think. After all, the advantage of becoming a franchisee is getting an off-the-shelf business package that includes a proven system, management and other training, employee manuals, marketing, and a product with a proven demand.

So becoming a franchisee sounds like the lowest-risk way to run that business you’ve dreamed of owning.

But is it?

Not Failing ≠ Success

Not failing is not the same as succeeding.

Succeeding means your total compensation is equal to—

1. A salary equivalent to your market value, including the long hours you’re putting in; plus,

2. A return on capital invested equal or greater than putting the same amount in an index fund, bonds, or other no-brainer interest, dividend, or profit opportunity.

Many businesses avoid failure—meaning liquidation or bankruptcy or simply closing down—while paying a below-average return to the founder(s).

Comparative data is hard to come by, but a table of defaults on loans from the SBA to franchisees is important food for thought for every potential franchisee.*

This data is skewed by the likelihood that people who turn to the SBA for loans have fewer financial resources and may thus be more likely to fail. On the plus side, the highest failure rates are for the lesser-known brands.

While this kind of data can be helpful in making a decision, ultimately it’s best to consider a franchise opportunity as both a business and an investment opportunity. As such, the selection process is similar to the steps outlined in chapter 6, “Finding the Next Starbucks ‘by Walking Around,’”).

With one major difference: as a shareholder in a publically traded company, if something goes wrong, you can dump your shares in a few moments with a single phone call to your broker (or a few clicks).

As a franchisee, you don’t have that option. So a cold assessment of the value, integrity, management ability, and market potential of a franchisor is of even greater importance.

And when you’re thinking of investing in a franchisor, evaluating the company from the perspective of a potential franchisee offers a valuable additional metric on that company’s performance.

Indeed, expressing an interest in becoming a franchisee gives you an entrée into gathering some information about the company that is not publically available from existing franchisees or the company itself.

Choosing a Franchisor

When Ray Kroc’s McDonald’s first began, the failure rate of its stores was exceptionally low. Two reasons:

• McDonald’s and its competitors benefited from a tailwind. The automobile and the postwar boom combined to spur the move from city to suburbs, resulting in the demand for new suburban shopping centers. Gas stations, other fast-food restaurants, 7-Elevens and similar stores, plus dozens of other retailers (including Walmart) moved into the low-ranks suburban “greenfields” where being first was a major factor in success (and the rents were low).

• Kroc and his team became experts in picking new locations that would be successful.

Today’s “greenfields” are no longer wide-open suburban spaces (except in poor, but fast-developing countries). Pretty much wherever you go these days you’ll see one chain store (whether franchised or company owned) after another, covering pretty much every imaginable market segment, with hardly an independent operator in sight.

So today’s opportunities are more likely to be found in niche markets and by following new technological trends and changing consumer tastes.

Though not always. According to Entrepreneur magazine, Subway, the world’s largest chain by number of stores, was America’s fastest-growing franchise in the years 2013 and 2014!2

Regardless, if you want to become a successful franchisee, the same principles behind McDonald’s early success apply today. The ideal franchisor is one benefiting from a tailwind with a high success rate (preferably 100 percent!) for newly opened outlets.

Location, Location, Location

As with a property investment, three key factors that are a major determinant of success for both franchisor and franchisee in opening a new retail establishment are location, location, and location.

Not all franchisors have franchisees’ success near the top of their list of priorities (see appendix 2, “A Quick Guide to Making Money in the Franchising Business,”). So the ideal franchisor is one whose financial incentives are aligned with yours (as a franchisee). That way, you’re both in the same financial boat.

While those factors are a good start, much more is involved. You’ll find a checklist of major factors in appendix 2, and some helpful links in appendix 4, “Resources.”

Your ultimate aim is another important factor. If you just want to be your own boss and live comfortably, purchasing or starting a single location of an existing franchise that will provide you with an above-average income can fulfill your desires.

But as a franchisee, you also have the potential of—

A Longer-Term Opportunity

Many people who become a franchisee with one McDonald’s, KFC, Burger King, Subway, 7-Eleven, or other chain then add second, third, and even dozens of additional stores, becoming multimillionaires.

Some go much farther.

Dave Thomas, who founded the Wendy’s hamburger chain, had his first job at twelve in a restaurant, spent three years in the US army as a mess sergeant, and cut his teeth in the franchising business with Kentucky Fried Chicken.

In 1968, he became a millionaire at age thirty-six when he sold his interest in a multistore KFC franchise for $1.5 million (1.5 million 1968 dollars is about $10.5 million today).

He opened the first Wendy’s a year later. The chain grew rapidly and recently (but temporarily, from 2013 to 2015) overtook Burger King as the number two hamburger franchise in the United States.

Country Franchises

But the possibilities in this field are far greater.

For example, Starbucks is now in 72 countries. That means it’s not in 134 others.

Even McDonald’s only operates in 119 countries—so 87 countries and territories are still open for franchising.

The master franchise for one of these countries could turn out to be a gold mine.

Especially a poor but fast-developing one, such as the Philippines—even though the average Filipino’s income is a mere 4.9 percent of an American’s.

Starbucks’ Philippines affiliate opened its first store in 1997. Today, twenty years later, there are 283 outlets, giving it an estimated value somewhere north of $150 million! It’s privately held so we don’t know the exact numbers, but even if my guesstimate is off $50 million either way, the potential is clear.

Similarly, when McDonald’s opened up in India in 1995, Amit Jatia became a 50 percent partner for West and South India. Today, his stake now 100 percent, his franchise is valued at around $900 million.3

And if not Starbucks or McDonald’s, there are hundreds of copycats—and other product categories—to choose from.

For example, Krispy Kreme operates in just 24 countries—meaning 182 countries are still open for expansion.

When Krispy Kreme opened its first store in Thailand, lines went around the block. Not just for the first few days: it was six months before the lines pretty much disappeared.

Stall owners from all over Bangkok bought dozens of boxes of Krispy Kreme doughnuts at a time—which they resold in markets and elsewhere at higher prices.

Franchising—with Venture Capital

Expansion opportunities exist even in highly competitive markets.

For example, in September 2015 Anil Patil, the UK’s first Starbucks franchisee, raised £10 million (US$15.3 million) from private-equity firm Connection Capital and the Royal Bank of Scotland to finance sixteen new Starbucks sites, with a hundred planned over the next five years.

A few more examples of successful international chains that may be candidates for expansion (or copycatting) in the rest of the world are:

Baskin-Robbins (www.baskinrobbins.com). 35 countries; not in 171 countries. USA. Specialty ice cream. Stores in Aruba, Australia, Bahrain, Canada, China, Colombia, Curaçao, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Panama, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Spain, Taiwan, Thailand, UAE, UK, USA, Vietnam, and Yemen.

Café Coffee Day (www.cafecoffeeday.com). 4 countries; not in 202 countries. India. Coffee café. 1,438 stores in Austria, Czech Republic, India, and Malaysia.

Crystal Jade (www.crystaljade.com). 11 countries; not in 195 countries. Singapore. An upmarket Chinese restaurant chain. In addition to Crystal Jade (Shanghainese food) it has seven other restaurant brands. 111 stores in China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, USA, and Vietnam.

J.CO (www.jcodonuts.com). 4 countries; not in 202 countries. Indonesia. A Krispy Kreme coffee and doughnuts clone—but sweeter. 231 stores in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore.

Kidzania (www.kidzania.com). 20 countries; not in 186 countries. Mexico. A working city scaled to four- to fourteen-year-olds. 20 “kid cities” in Brazil, Chile, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kuwait, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, Portugal, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, Turkey, UAE, and UK. Soon to open in Doha, and USA.

Krispy Kreme (www.krispykreme.com). 28 countries; not in 178 countries. USA. Coffee and doughnuts. 1,004 stores in Australia, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Canada, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, Puerto Rico, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, UAE, UK, and USA.

Little Kickers (www.littlekickers.co.uk). 19 countries; not in 187 countries. UK. “Learn through play”: a preschool football (soccer) academy. 210 franchises in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Cyprus, Ecuador, England, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Scotland, South Africa, and UK.

TWG Tea (www.twgtea.com). 13 countries; not in 193 countries. Singapore. Luxury tea brand. 56 stores in Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, UK, UAE and Vietnam; products distributed through third parties in Canada and the United States.

These are just a handful of thousands of possibilities. Find more in the links in appendix 4, “Resources,”.

Multiple Franchises

Another model is the multiple franchisee: a company that holds franchises for a variety of different brands.

The “granddaddy” of this concept is Yum! Brands, which owns Pizza Hut, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Taco Bell, and WingStreet, a chicken-wings chain the company launched in 2003. All WingStreet stores are colocated with Pizza Hut.

However, the giants of this model, at least in terms of the number of brands, are in the rest of the world, especially in countries where foreigners are prohibited from owning retail outlets. For example, consider—

Jollibee’s Operating Model

Jollibee—the Philippines’ answer to McDonald’s—began as a Magnolia ice cream parlor in 1975. In 1978, it switched focus to hot dogs and burgers. Today it has transformed itself into an operator of multiple franchises.

By purchasing other brands and starting its own in addition to Jollibee (a McDonald’s copycat, see here), the parent company, Jollibee Foods Inc., also owns Mang Inasal (Filipino-style chicken), Greenwich (the Philippines’ answer to Shakey’s and Pizza Hut), Chowking (Chinese fast food), and Red Ribbon (cakes)—plus the Philippines’ franchise for Burger King.

With a total of 2,335 stores in the Philippines, just about anywhere you see a Jollibee you’ll see one or more of these other franchises next door. Jollibee’s bulk-buying clout gives it the power to negotiate lower prices for everything from property rental to paper cups, menu ingredients, and media buying.

Jollibee’s operational model of scaling up through multiple franchises has transformed it into the Philippines’ largest franchised-food operator.

The company has taken its operating model worldwide, initially by targeting overseas Filipinos in such markets as Hong Kong, Singapore, Daly City, California, and the Middle East with its domestic brands, and then by purchasing other franchises or entering joint ventures.

Today, its biggest market after the Philippines is China, where it has 422 stores, followed by the USA (86), and Vietnam (72).

From a single store in 1978, it has grown into a $4 billion company with operations in seventeen countries:

Jollibee is now extending its reach through a series of joint ventures, which give the company partial interests in Highlands Coffee (101 stores in Vietnam and the Philippines), Vietnamese restaurant chain Pho 24 (36 stores in Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia, Korea, and Australia), plus Hard Rock Cafe franchises in Hong Kong, Macau, and Vietnam, and 12 Hotpot (21 stores in China).

In 2015, Jollibee added Dunkin’ Donuts (China) to its brands, in a 60 percent-owned joint venture with a Singapore-based investment firm. Jollibee also announced plans to expand its wholly owned operations into Canada, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, and Europe from 2015 to 2017.

Jollibee is far from the only international multifranchise operator. A few other examples:

Australia:

Withers Group: 7-Eleven, Starbucks

Retail Food Group: eleven food brands including Donut King, Pizza Capers, and Gloria Jean’s

Canada:

QSR: Burger King, Tim Hortons

Hong Kong:

Jardine Matheson: Pizza Hut, Kentucky Fried Chicken

Maxim’s (50 percent owned by Jardine Matheson): Starbucks, plus sixty-four locally branded restaurants including twenty-four Chinese, fourteen Western, seven Japanese, and eight fast-food

Philippines:

Global Restaurant Concepts: California Pizza Kitchen, P.F. Chang’s, IHOP, Morelli’s Gelato, Mad for Garlic, Gyu-Kaku, Ramen Iroha

Singapore:

Osim: Osim, RichLife (China), TWG Tea (70 percent owned); GNC (franchisee for Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, Australia)

South Africa:

Taste Holdings: Domino’s Pizza, Starbucks

Vietnam:

VTI: Highlands Coffee, Pho 24, Hard Rock Cafe, Emporio Armani Caffè, Meet and Eat, Nineteen 11, Swarovski, Aldo

Franchising: A Two-Way Flow

Most of the world’s major franchising chains were “made in America.” Their success led to franchising’s becoming a big business all around the world. With the result, today, that franchising has become a two-way street, with many foreign-based franchisors expanding into the United States. A few examples:

Australia: Floral Image (floralimage.com), corporate flowers. Cherry Blow Dry Bar (www.cherryblowdrybar.com).

Belgium: Le Pain Quotidien (“daily bread,” www.lepainquotidien.com), French café/restaurant.

Canada: Smoke’s Poutinerie (www.smokespoutinerie.com). Poutine is a Quebec favorite: french fries with toppings. Smoke’s is aggressively expanding in the United States, the Middle East (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and UAE), and elsewhere.4

Japan: Gyu-Kaku (www.gyu-kaku.com), Japanese BBQ.

Philippines: Potato Corner (www.potatocorner.com.ph, dev.potatocornerusa.com), flavored french fries. Over 550 outlets worldwide, including in Australia, Indonesia, Panama, United Arab Emirates; aggressively expanding in the United States (31 stores, and counting).5

Romancing California Pizza Kitchen

Armando “Archie” Rodriguez “fell in love” with California Pizza Kitchen in the early 1990s while working for video-game company Sega in San Francisco and became determined to bring it to the Philippines.

While on vacation in Manila in 1995, he was amazed by the long lines at TGI Fridays.

“That’s what drove my quest to acquire CPK,” he recalls. Right away, he sent a letter to CPK officials in Los Angeles.

But—as all its US stores were then (and still are) company owned—franchising was not on the company’s map at the time. So the answer was “No!”

The following year Rodriguez returned to the Philippines and started an Internet business, which he sold three years later. That was followed by a successful Mexican-themed restaurant and bar chain named Tequila Joe’s.

Nevertheless, Rodriguez continued to woo CPK, sending them a business proposal every three months until, in 1998—three years after his first proposal—the American company agreed.

Rodriguez recalls CPK founder Larry Flax’s jest when he came for CPK Philippines’ tenth anniversary in 2008.

“We didn’t know what the Philippines was, and it was so far away. If something wrong happened, nobody would hear about it,” Rodriguez quoted Flax as saying.

In reality, it was Rodriguez’s dogged persistence and lucid business plan that convinced CPK to hand out its first franchise to him. [Emphasis added.]

Today, though Tequila Joe’s has folded, Rodriguez’s company has flowered into a seven-brand, multimillion-dollar multifranchise operation that is now set to expand Asia-wide.

As the ancient Chinese divination text the I Ching puts it, “Perseverance furthers.”

Note: Pret A Manger (http://www.pret.co.uk), the successful British sandwich and coffee chain that is expanding worldwide, whose stores are all company owned, may be a candidate for the Rodriguez Romancing Approach.*

“Reverse Engineering” Niche Markets

Another way to spot a business opportunity is to “reverse engineer” a profitable business in a tiny niche market in another, smaller country.

Normally, the flow is the other way around: from larger, richer countries to smaller, poorer ones.

For example, in my teens and twenties, I recall being impressed by ads in American magazines from Popular Mechanics to Scientific American and Psychology Today (okay—and Playboy) for hundreds of products and specialized gadgets that were simply not available in Australia.

Such a greater variety of merchandise results from a larger population and/or higher incomes, combined with lower-cost infrastructure, which create smaller and smaller niche markets.

One business to spring from this combination of factors was Sears, Roebuck.

Formed in 1886 to sell watches by mail order, by 1896 it was offering a wide range of low-priced merchandise through its catalog to rural farms and villages that had no other convenient access to retail outlets.

What made Sears, Roebuck’s success possible was the expansion of railroads plus low-cost delivery thanks to the US Post Office, which made its market nationwide.

Plus, crucially, the market’s size.

In 1889, the US population was 61.6 million. Sears, Roebuck’s “niche” was eventually 10 million–plus. Sears, along with its competitor Montgomery Ward, became household names.

By comparison, in that same year Australia’s population was 3.08 million, spread out over an area similar in size to the US mainland. Even with the same per capita income, Australia (and other smaller countries) could not support the necessary infrastructure to offer a similar niche for a Sears clone to prosper.

Today, more than a century later, not much has changed (relatively speaking). Australia’s population is 21.6 million compared to 318.9 million for the United States. California alone—with 38.8 million people*—is a market 79 percent bigger than the whole of Australia.

So today, as over a century ago, the United States supports a far wider range of niche businesses than smaller countries such as Australia. There is, in economic terms, a greater division (and specialization) of labor and production.

From Niche—to a New Industry

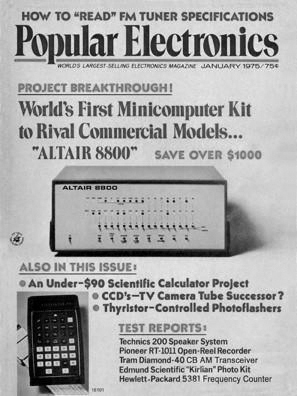

A more recent example, one that started an entirely new industry: the Altair 8800 microcomputer.

Featured on the cover of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics, the Altair 8800 was $395 as a kit to be put together by the purchaser. Assembled, it cost $498.

It was designed and built by Ed Roberts, president of MITS Incorporated, in a desperate gamble to save his company. MITS was a successful producer of electronic calculators—until Texas Instruments entered the market and, by mid-1974, had cut calculator prices in half, devastating MITS’s until-then cash cow.

The operating system for the Altair 8800, Altair BASIC, was written by … Bill Gates and Paul Allen, which led to the founding of Microsoft.

Roberts needed two hundred sales of the Altair kit to break even. Within three months, four thousand had been sold by mail order, and MITS couldn’t keep up with demand.6

He was lucky: an entirely new product featured on a magazine cover jump-started sales. Even without that jump start, hobbyists and the advertising media to reach them (such as Popular Electronics) made the Altair 8800 a viable niche product.

In the United States, the market’s size and reliable, low-cost infrastructure made nationwide delivery economical. No other market at that time could have supported a similar product.

By turning this around and scouring smaller markets for successful niche products, it is possible to find proven business opportunities that can be imported from the smaller to the larger country. One example:

UGG Boots

Both Australia and New Zealand claim to have invented “UGG boots.” These are boots made from sheepskin, with the wool inside. They are wonderfully warm in winter.

The name was trademarked in Australia and New Zealand, but not elsewhere. The boots were imported to the United States, where they became a trendy item with surfers, mainly in Orange County. Eventually, Deckers Outdoor Corporation bought the importing business and registered the trademark in the United States in 1999, and then in many other countries.

This product came to the attention of the American company as a result of inroads into the US market made by Australian exporters.

Today, thanks to the Internet, it’s much easier to find niche businesses like UGG boots that are successful in smaller markets before they expand internationally.

There’s an important comparison to be made between the Altair 8800 and UGG boots: each resulted from that market’s specialty.

The Altair 8800 could only have been developed in the United States as, at that time, it was the only place in the world where all the parts and relevant expertise were readily available.

Australia and New Zealand are both major exporters of wool, and UGG boots developed from that specialty. Sheep shearers wrapped sheepskins around their feet to keep them warm and dry; from that beginning, they became a commercial product in the 1930s.

When looking for business opportunities in other countries, focus on the product areas they are best known for.

Another Take on Niche Markets

The United States is not the only market that has the potential to support multiple, tiny niche businesses.

Imagine a business that appeals to just a hundred people per million and can be profitable with just five thousand or so customers.

The following table shows the potential market size for this niche product in eight different countries adjusted (in the right-hand column) for differences in per capita wealth.

Intriguingly, only five countries’ domestic markets, other than that of the United States, can support our imaginary hundred-per-million product: Germany, Japan, Brazil, China, and India. Though infrastructure costs may force Brazil and India off the list—for the moment.

So another source of business ideas is to search for successful niche products in markets of similar (or smaller) size and wealth to your own.