2.8. Vector Dot and Cross Products

(2.20)

(2.20)

(2.21)

(2.21)

(2.20)

(2.20)

(2.21)

(2.21)

(2.22)

(2.22)

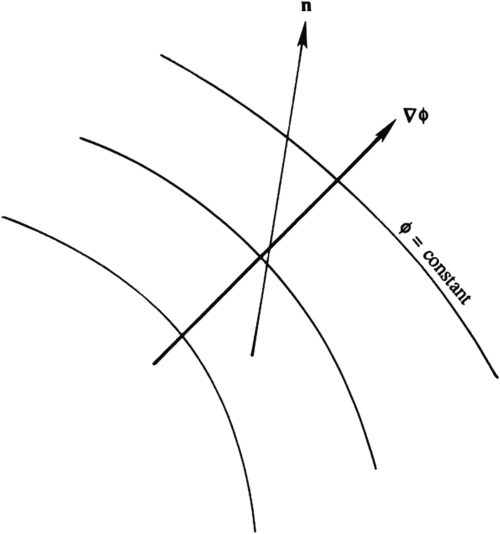

. The vector ∇ϕ is called the gradient of ϕ, and ∇ϕ is perpendicular to surfaces defined by ϕ = constant. In addition, it specifies the magnitude and direction of the maximum spatial rate of change of ϕ (Figure 2.7). The spatial rate of change of ϕ in any other direction n is given by:

. The vector ∇ϕ is called the gradient of ϕ, and ∇ϕ is perpendicular to surfaces defined by ϕ = constant. In addition, it specifies the magnitude and direction of the maximum spatial rate of change of ϕ (Figure 2.7). The spatial rate of change of ϕ in any other direction n is given by:

(2.23)

(2.23)

, of a second-order tensor T can be defined as the vector whose j-component is:

, of a second-order tensor T can be defined as the vector whose j-component is:

(2.24)

(2.24)

(2.25)

(2.25)

(2.26)

(2.26)

(2.27)

(2.27)

(2.28)

(2.28)

–

–  , but this can also be written

, but this can also be written  because Sij and

because Sij and  are symmetric. Now, replace the index j by k and the index i by l to find:

are symmetric. Now, replace the index j by k and the index i by l to find: (2.29)

(2.29)

, and:

, and:

(2.30)

(2.30)

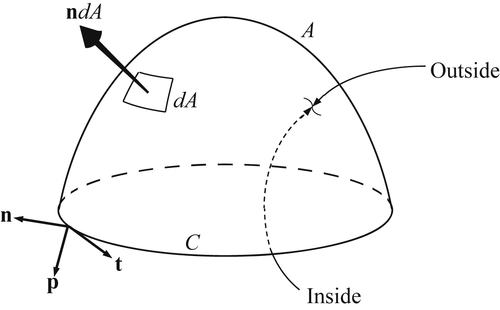

, of Q when considered in its limiting form for a vanishingly small volume:

, of Q when considered in its limiting form for a vanishingly small volume: (2.31)

(2.31)

(2.32, 2.33)

(2.32, 2.33)

(2.34)

(2.34)

(2.35)

(2.35)

where b = (1, 4, 17) and c = (–4, –3, 1).

where b = (1, 4, 17) and c = (–4, –3, 1). where u a vector with components ui.

where u a vector with components ui. , where

, where  and h is a constant vector with components hi.

and h is a constant vector with components hi. , where u = Ω × x and Ω is a constant vector with components Ωi.

, where u = Ω × x and Ω is a constant vector with components Ωi. , where

, where

.

. to indicial notation and show that it is zero in Cartesian coordinates for any twice-differentiable scalar function ρ.

to indicial notation and show that it is zero in Cartesian coordinates for any twice-differentiable scalar function ρ. .]

.]

. Then show that AijAji and AijAjkAki are also invariants. In fact, all contracted scalars of the form AijAjk ċċċ Ami are invariants. Finally, verify that

. Then show that AijAji and AijAjkAki are also invariants. In fact, all contracted scalars of the form AijAjk ċċċ Ami are invariants. Finally, verify that  , and

, and  . Because the right-hand sides are invariant, so are I2 and I3.]

. Because the right-hand sides are invariant, so are I2 and I3.] , and the Pythagorean theorem to show that u·v = 0 when u and v are perpendicular.

, and the Pythagorean theorem to show that u·v = 0 when u and v are perpendicular. is the length of x.

is the length of x. for any twice-differentiable vector function u regardless of the coordinate system.

for any twice-differentiable vector function u regardless of the coordinate system. for any single-valued twice-differentiable scalar ϕ regardless of the coordinate system.

for any single-valued twice-differentiable scalar ϕ regardless of the coordinate system.