8.4. Standing Waves

The wave motion results presented so far are for one propagation direction (+x) as specified by (8.2). However, a small-amplitude sinusoidal wave with phase (kx + ωt) can be an equally valid solution of (8.11). Such a waveform:

(8.61)

(8.61)

only differs from (8.2) in its direction of propagation. Its wave crests move in the –x-direction with increasing time. Interestingly, non-propagating waves can be generated by superposing two waves with the same amplitude and wavelength that travel in opposite directions. The resulting surface displacement is

Here, it follows that η = 0 at kx = ±π/2, ±3π/2, etc., for all time. Such locations of zero surface displacement are called nodes. In this case, deflections of the liquid surface do not travel. The surface simply oscillates up and down at frequency ω with spatially varying amplitude, keeping the nodal points fixed. Such waves are called standing waves. The corresponding stream function, a direct extension of (8.37), includes both the cos(kx−ωt) and cos(kx + ωt) components:

(8.62)

(8.62)

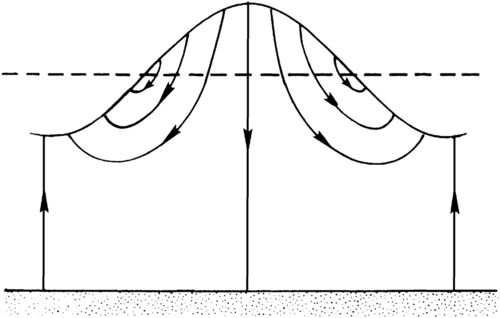

The instantaneous streamline pattern shown in Figure 8.11 should be compared with the streamline pattern for a propagating wave (Figure 8.5).

Standing waves may form in a limited body of water such as a tank, pool, or lake when traveling waves reflect from its walls, sides, or shores. A standing-wave oscillation in a lake is called a seiche (pronounced “saysh”), in which only certain wavelengths and frequencies ω (eigenvalues) are allowed by the system. Consider a rectangular tank (an ideal lake) of length L with uniform depth H and vertical walls (shores), and assume that the waves are invariant along y. The possible wavelengths are found by setting u = 0 at the two walls. Here, u = ∂ψ/∂z, so (8.62) gives:

(8.63)

(8.63)

Figure 8.11 Instantaneous streamline pattern in a standing surface gravity wave. Here, the ψ = 0 streamline follows the bottom and jumps up to contact the surface at wave crests and troughs where the horizontal velocity is zero. If this standing wave represents the n = 1 mode of a reservoir of length L with vertical walls, then L = λ/2 is the distance between a crest and a trough. If it represents the n = 2 mode, then L = λ is the distance between successive crests or successive troughs.

Taking the walls at x = 0 and L, the condition of no flow through the vertical sidewalls requires u(x = 0) = u(x = L) = 0. For non-trivial wave motion, this means sin(kL) = 0, which requires:

so the allowable wavelengths are:

(8.64)

(8.64)

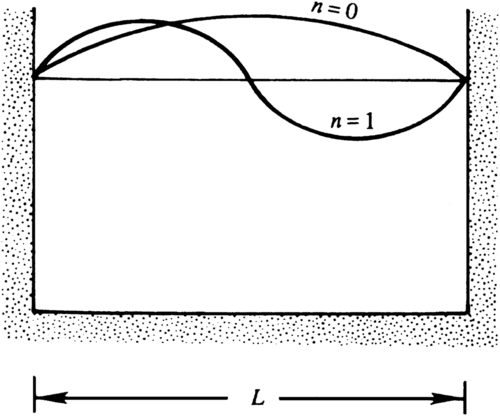

The largest possible wavelength (n = 1) is 2L and the next largest (n = 2) is L (Figure 8.12). The allowed frequencies can be found from the dispersion relation (8.28):

(8.65)

(8.65)

Figure 8.12 Distributions of horizontal velocity u for the first two normal modes in a lake or reservoir with vertical sides. Here, the boundary conditions require u = 0 on the vertical sides. These distributions are consistent with the streamline pattern of Figure 8.11.