11.9. Inviscid Stability of Parallel Flows

Insight into the viscous stability of parallel flows can be obtained by first assuming that the disturbances obey inviscid dynamics. The governing equation can be found by setting ν = 0 in the Orr-Sommerfeld equation, (11.79), giving:

(11.81)

(11.81)

which is called the Rayleigh equation. If the flow is bounded by walls at y1 and y2 where v = 0, then the boundary conditions are:

(11.82a)

(11.82a)

If the region of shear in the basic flow is localized near y = 0, then the disturbance must decay away from this region so its boundary conditions are:

(11.82b)

(11.82b)

The set (11.81) and (11.82) defines an eigenvalue problem, with c(k) as the eigenvalue and ϕ as the eigenfunction. As these equations do not involve the imaginary root, i, taking the complex conjugate shows that if ϕ is an eigenfunction with eigenvalue c for some k, then ϕ∗ is also an eigenfunction with eigenvalue c ∗  for the same k. Therefore, to each eigenvalue with a positive ci there is a corresponding eigenvalue with a negative ci. In other words, to each growing mode there is a corresponding decaying mode. Stable solutions therefore can have only a real c. Note that this is true of inviscid flows only. The viscous term in the full Orr-Sommerfeld equation (11.79) involves an i, and the foregoing conclusion is no longer valid.

for the same k. Therefore, to each eigenvalue with a positive ci there is a corresponding eigenvalue with a negative ci. In other words, to each growing mode there is a corresponding decaying mode. Stable solutions therefore can have only a real c. Note that this is true of inviscid flows only. The viscous term in the full Orr-Sommerfeld equation (11.79) involves an i, and the foregoing conclusion is no longer valid.

for the same k. Therefore, to each eigenvalue with a positive ci there is a corresponding eigenvalue with a negative ci. In other words, to each growing mode there is a corresponding decaying mode. Stable solutions therefore can have only a real c. Note that this is true of inviscid flows only. The viscous term in the full Orr-Sommerfeld equation (11.79) involves an i, and the foregoing conclusion is no longer valid.

for the same k. Therefore, to each eigenvalue with a positive ci there is a corresponding eigenvalue with a negative ci. In other words, to each growing mode there is a corresponding decaying mode. Stable solutions therefore can have only a real c. Note that this is true of inviscid flows only. The viscous term in the full Orr-Sommerfeld equation (11.79) involves an i, and the foregoing conclusion is no longer valid.Starting from (11.81) it is possible to show that certain velocity distributions U(y) are potentially unstable. In this discussion it should be noted that only the disturbances are assumed to obey inviscid dynamics; the background flow profile U(y) may be that of a steady laminar viscous flow.

The first deduction that can be made from (11.81) is Rayleigh's inflection point criterion: a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for instability of an inviscid parallel flow is that the basic velocity profile U(y) has a point of inflection. To prove the theorem, rewrite the Rayleigh equation (11.81) in the form:

and consider the unstable mode for which ci > 0, and therefore U – c ≠ 0. Multiply this equation by ϕ ∗  , integrate from the lower to the upper boundary of the flow, by parts where necessary, and apply the boundary condition (11.82). The first term transforms as follows:

, integrate from the lower to the upper boundary of the flow, by parts where necessary, and apply the boundary condition (11.82). The first term transforms as follows:

, integrate from the lower to the upper boundary of the flow, by parts where necessary, and apply the boundary condition (11.82). The first term transforms as follows:

, integrate from the lower to the upper boundary of the flow, by parts where necessary, and apply the boundary condition (11.82). The first term transforms as follows:

where the limits on the integrals have not been explicitly written. The Rayleigh equation then gives:

(11.83)

(11.83)

The first term is real. The second term in (11.83) is complex, and its imaginary part can be found by multiplying the numerator and denominator by (U – c ∗  ). Thus, the imaginary part of (11.83) implies:

). Thus, the imaginary part of (11.83) implies:

). Thus, the imaginary part of (11.83) implies:

). Thus, the imaginary part of (11.83) implies: (11.84)

(11.84)

For the unstable case, for which ci ≠ 0, (11.84) can be satisfied only if d2U/dy2 changes sign at least once in the interval y1 < y < y2, or –∞ < y < +∞. In other words, for instability the background velocity distribution must have at least one point of inflection (where d2U/dy2 = 0) within the flow. Clearly, the existence of a point of inflection does not guarantee a non-zero ci. The inflection point is therefore a necessary but not sufficient condition for inviscid instability.

Some seventy years after Rayleigh’s discovery, the Swedish meteorologist Fjortoft in 1950 discovered a stronger necessary condition for the instability of inviscid parallel flows. He showed that a necessary condition for instability of inviscid parallel flows is that (U – U1)(d2U/dy2) < 0 somewhere in the flow, where U1 is the value of U at the point of inflection. To prove the theorem, take the real part of (11.83):

(11.85)

(11.85)

Suppose that the flow is unstable, so that ci ≠ 0, and a point of inflection does exist according to the Rayleigh criterion. Then it follows from (11.84) that:

(11.86)

(11.86)

Adding equations (11.85) and (11.86), we obtain:

so that (U – U1)(d2U/dy2) must be negative somewhere in the flow.

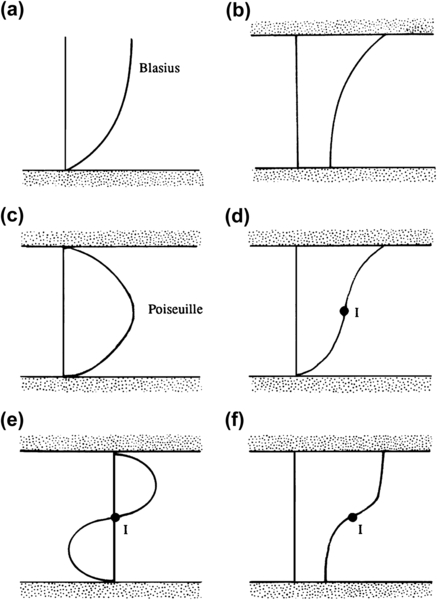

Some common velocity profiles are shown in Figure 11.21. Only the two flows shown in the bottom row can possibly be unstable, for only they satisfy Fjortoft’s theorem. Flows (a), (b), and (c) do not have an inflection point: flow (d) does satisfy Rayleigh’s condition but not Fjortoft’s because (U – U1)(d2U/dy2) is positive. Note that an alternate way of stating Fjortoft’s theorem is that the basic flow's vorticity magnitude must have a maximum within the region of flow, not at the boundary. In flow (d), the maximum magnitude of vorticity occurs at the walls.

The criteria of Rayleigh and Fjortoft indicate the importance of having a point of inflection in the velocity profile. They show that flows in jets, wakes, shear layers, and boundary layers with adverse pressure gradients, all of which have a point of inflection and satisfy Fjortoft’s theorem, are potentially unstable. On the other hand, plane Couette flow, Poiseuille flow, and a boundary-layer flow with zero or favorable pressure gradient have no point of inflection in the velocity profile and are stable in the inviscid limit.

Figure 11.21 Examples of parallel flows. Points of inflection are denoted by I. Profiles (a), (b), and (c) are inviscidly stable. Profiles (d), (e), and (f) may be inviscidly unstable by Rayleigh’s inflection point criterion. Only profiles (e) and (f) satisfy Fjortoft's criterion of inviscid instability.

However, neither of the two conditions is sufficient for instability. An example is the sinusoidal profile U = sin(y), with boundaries at y = ±b. It has been shown that the flow is stable if the width is restricted to 2b < π, although the profile has an inflection point at y = 0.

Invisicd parallel flows satisfy Howard’s semicircle theorem, which was proved in Section 11.7 for the more general case of a stratified shear flow. The theorem states that the phase speed cr of an unstable mode with wave number k has a value that lies between the minimum and the maximum values of U(y) in the flow field. Growing and decaying modes are characterized by a non-zero ci, whereas neutral modes can have only a real c = cr. Thus, it follows that neutral modes must have U = c somewhere in the flow field. The neighborhood y around yc at which U = c = cr is called a critical layer. The location yc is a critical point of the inviscid governing equation (11.81), because the highest derivative drops out at this value of y, and the eigenfunction for this k and c may be discontinuous across this layer. The full Orr-Sommerfeld equation (11.79) has no such critical layer because the highest-order derivative does not drop out when U = c. It is apparent that in a real flow a viscous boundary layer must form at the location where U = c, and that the layer becomes thinner as Re → ∞.

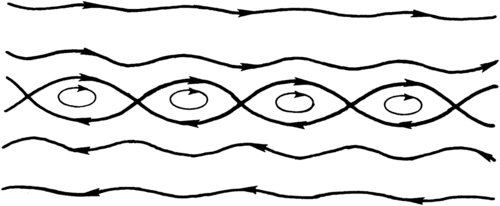

Figure 11.22 The Kelvin cat's eye pattern near a critical layer, showing streamlines as seen by an observer moving with a neutrally stable wave having c = cr. This flow pattern is reminiscent of those shown in Figures 11.4–11.6.

The streamline pattern in the neighborhood of the critical layer where U = c was given by Kelvin in 1888, and indicates the nature of the nearby unstable modes having the same k but small positive ci. The discussion provided here is adapted from Drazin and Reid (1981). Consider a flow viewed by an observer moving with the phase velocity c = cr. Then the basic velocity field seen by this observer is (U – c), so that the stream function due to the basic flow is:

The total stream function is obtained by adding the perturbation:

(11.87)

(11.87)

where A is an arbitrary constant, and the time factor in the second term is omitted because the disturbance is neutrally stable. Near the critical layer y = yc, a Taylor series expansion of the real part of (11.87) is approximately:

where ϕ(yc) is assumed to be real. The streamline pattern corresponding to this equation is sketched in Figure 11.22, showing the so-called Kelvin cat’s eye pattern that is visually similar to the illustrations of the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability given in Figures 11.4–11.6.