PECKINPAH AND 1970s CINEMA

Peckinpah, along with directors such as Arthur Penn, Stanley Kubrick and Robert Altman, can be regarded as a transitional figure in American cinema, bridging the gap between 1950s auteurs like Robert Aldrich, Nicholas Ray and Elia Kazan and the later ‘Movie Brats’ of the 1970s. This was the first generation of directors to work in television. They were also the first wave of American directors to be demonstrably influenced by foreign (that is, non-Hollywood) cinema:1 Altman openly lifted from Ingmar Bergman for Images (1972), and Bonnie and Clyde (1967) passed from Jean-Luc Godard to François Truffaut before ending up with Arthur Penn.

The critical reappraisal of a number of studio system-era directors that had begun in France and spread to the US was also a contributing factor to the vibrant film culture of the 1950s and 1960s, with the auteur theory positing that it was possible to make personal films in the factory-like context of Hollywood. In a piece on Bonnie and Clyde, Philip French quotes the film´s screenwriters, Robert Benton and David Newman, who accurately sum up this heady period:

We were riding the crest of a new wave that had swept in on our minds, and the talk was Truffaut, Godard, DeBroca, Bergman, Kurosawa, Antonioni, Fellini and all the other names that fell like a litany in 1964, along with the sudden and staggering heights of rediscovery around the pantheon people – Hitchcock, Hawks, Ford, Welles and the rest. (2007)

Accordingly, Peckinpah’s work is influenced by the twin traditions of Hollywood genre filmmaking and auteur cinema from Europe and beyond. Among the directors he expressed admiration for are Huston, Wilder, John Ford and George Stevens as well as Bergman, Kurosawa and Alain Resnais (see Seydor 1980: 266). Peckinpah and his contemporaries began by making what were more or less conventional genre films and moved on to a more experimental, expressive style throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s. The evolution in Peckinpah’s filmmaking, from Ride the High Country (1962) to Alfredo Garcia is mirrored in the work of Penn, Kubrick and Altman: compare The Delinquents (Altman, 1957) to Nashville (1975), The Killing (Kubrick, 1956) to A Clockwork Orange (1971) or The Miracle Worker (Penn, 1962) to Night Moves (1975).

For some years now, the pre-Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) director-friendly 1970s have been mythologised as a time of unprecedented freedoms (see Corrigan 1991, Kolker 2000, or, for a more gossipy account, Biskind 1998). The falloff in cinema audiences from the mid-1960s onwards and the emergence of the counterculture led to a period of uncertainty for the film industry, with a new generation of directors and producers taking advantage of this temporary crisis. Producers such as Robert Evans and Bert Schneider and directors including Coppola, Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin, Bob Fosse and Hal Ashby managed to build careers making recognisably personal films. The pre-VCR tradition of the ‘midnight movie’ saw oddball talents such as George Romero, Alejandro Jodorowsky and John Waters find an audience. In the wake of Night of the Living Dead (Romero, 1968), the American horror film moved into a new golden age, wherein vampires and monsters were replaced by cannibal families in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes (Wes Craven, 1977). The decade also saw a number of veterans coming up with some weird, offbeat projects that took full advantage of both the industrial uncertainty of the times and the collapse of the Production Code. Consider the heated Southern Gothic of The Beguiled (from Peckinpah mentor, Don Siegel, 1971). Or the drunks and washed-up boxers of Fat City (John Huston, 1972). Arthur Penn’s wacky westerns, Little Big Man (1970) with a centenarian Dustin Hoffman and The Missouri Breaks (1976) with a cross-dressing, psychotic Marlon Brando. Or the bleak and grimy Hustle (Robert Aldrich, 1975) which teamed Burt Reynolds with Catherine Deneuve. Even a hack like Arthur Hiller came up with The Hospital (1971), an impressive adaptation of a characteristically sour Paddy Chayevsky script. But even in the freewheeling 1970s, this (last?) Golden Age of American movies, this period of ‘pessimism and permissiveness’ (Mathijs 2008: 30), Peckinpah had difficulty making films free of studio interference.

From his little-seen debut film The Deadly Companions (1961) on, his fortunes had been distinctly mixed. His second film, Ride the High Country, received some excellent reviews but the would-be epic Major Dundee (1964) was butchered by the studio. After being fired from the Steve McQueen vehicle The Cincinatti Kid that same year (after only four days of shooting) he was blacklisted for years before a triumphant comeback with The Wild Bunch. By 1974, his stock had fallen considerably, despite the commercial success of The Getaway. The uncharacteristically gentle The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970) had been a flop and Straw Dogs, while successful, had proved a turn-off to many and divided critics: Pauline Kael infamously dubbed it ‘the first American film that is a fascist work of art’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 210). Added to this was his growing (some would say hard-earned) reputation as an angry drunk who was loath to compromise. His last picture prior to Alfredo Garcia, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), made for MGM, had been taken away from him, savagely recut and released to poor box office and terrible reviews (the New Republic considered that ‘this stale saga is dull, slow and sillily portentous’, while for Newsweek, it was ‘a misshapen mess’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 260)). The reasons for this will be discussed in more depth later but James Aubrey, the Head of Production at MGM, had become another hate figure for Peckinpah, no stranger to meddling studios and producers. Aubrey was the most recent in a long line of sleazy, greedy suits who screwed him and mangled his movie (‘The saying is they can kill you but not eat you. That’s nonsense. I’ve had them eating on me while I was still walking around’ (Peckinpah quoted in Butler 1979: 8)). This depressing experience had exacerbated the drinking that had been a problem for most of his adult life. It also encouraged the self-pitying view Peckinpah had of himself, not without foundation, as a great artist beset by moneymen and philistines. Alfredo Garcia was his attempt to make a film without compromises, making no concessions, either to United Artists (UA) or the audience. The budget of $1.5 million was low and it shows onscreen: for the novelist Rick Moody, the film is ‘more like the B-films of Roger Corman than John Ford’ (2009).

GENESIS

The genesis of the film came from Frank Kowalski, an old friend of the director. During the shooting of The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Kowalski brought Peckinpah the bare bones of a story about a bartender who is sent by a Mafia don to cut the head off a corpse. Kowalski was also interested in the story of Caryl Chessman. Known as ‘The Red Light Bandit’, Chessman was a charismatic robber and rapist who wrote a number of best-selling books during a ten-year stretch on Death Row before his execution in 1960.

The script was worked on over the next three years with Kowalski dropping out and Gordon Dawson taking his place. Interviewed for Tom Thurman’s feature documentary Sam Peckinpah’s West (2004), Dawson claimed he ended up writing the final version of the script in ten days and was paid $10,000. Even a cursory glance at the credits of Kowalski and Dawson tells us a lot about the oddball pedigree of the film. Kowalski had an uncredited bit part in the James Cagney film Angels with Dirty Faces (Michael Curtiz, 1938) and had worked in various capacities on an eclectic mix of projects: script supervising for The Outer Limits television show (1963–65) and providing continuity on the cult film Sex Kittens Go To College (Albert Zugsmith, 1960) starring Mamie Van Doren and Conway Twitty ‘as himself’. His only previous screenwriting credit was for the western A Man Called Sledge (1970), which he co-wrote with the director/star, Vic Morrow. But his ‘dialogue supervisor’ credit on The Ballad of Cable Hogue may be misleading. According to the star of the film, Jason Robards, Kowalski was responsible for ‘anything [in the script] that was funny or had real humour. Frank was invaluable to Sam. He had a mind’ (in Fine 2005: 164). Dawson had been a part of Peckinpah’s circle since Major Dundee. He had worked on five of the director’s films, moving from costume and wardrobe to second unit director on The Getaway to screenwriter and associate director. During the Alfredo Garcia shoot, he walked off the set, disgusted by Peckinpah’s behaviour and vowing never to work with the director again:

He really lost it on Alfredo … I had him up there on the pedestal. My fault for putting him up there, you know, that’s a tough place to be but he sure fell off on that picture and I couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty back together again in my mind. (In Weddle 1994: 494)

Dawson has worked mainly in television since then, writing for popular shows like The Rockford Files (1974–80), Diagnosis Murder (1993–2001) and Baywatch Nights (1995–97).

Much has been made of Peckinpah’s struggles with producers and moneymen of all stripes (take Marshall Fine’s statement that, after Major Dundee, the director ‘was even more convinced that producers were not a necessary evil –they were just plain evil’ (2005: 101)). But his relationship with Martin Baum, the producer of Alfredo Garcia, was an unusually long-lasting and productive one. Baum had been the President of ABC Pictures and helped bring a number of impressive projects to the screen, including The Grissom Gang (Robert Aldrich, 1971), Cabaret (Bob Fosse, 1972) and Straw Dogs, before he went on to form his own production company, Optimus, with financing from United Artists. Although his relationship with Peckinpah soured during the shoot of the 1975 film The Killer Elite (largely due to the latter’s new-found enthusiasm for cocaine), when Baum joined Creative Artists Agency, he became the director’s agent.

CASTING: OATES ET LES AUTRES

The casting was untypical for a Peckinpah film as it contained few members of his regular stock company of actors (such as Strother Martin, L. Q. Jones, E. G. Marshall), many of whom had been with him since his television work in the 1950s. It does, however, bring to mind the comment made about the cast of The Man Who Fell to Earth (Nicolas Roeg, 1975): ‘That’s a dinner party, not a cast’ (thevoid99: 2007). For the lead role, Peckinpah had first approached his friend and frequent collaborator James Coburn, but Coburn hated the idea (‘I said, why would you want to do this?’ (in Fine 2005: 268)). Peter Falk, TV cop Columbo (1968–97) and a member of the John Cassavetes stock company, was interested but too busy. It is no surprise that Peckinpah ended up casting Warren Oates as Bennie. The Kentucky-born actor was a Peckinpah veteran, appearing in Ride the High Country, Major Dundee and The Wild Bunch, as well as the television show, The Rifleman (1958–63). Oates was a major talent and a significant figure in 1970s Hollywood. He featured in three impressive directorial debuts, The Hired Hand (Peter Fonda, 1971) Badlands (Terrence Malick, 1973) and Dillinger (John Milius, 1973) as well as a number of films for cult director (and Peckinpah friend/collaborator) Monte Hellman. He also appeared in films by Friedkin, Steven Spielberg, Norman Jewison and Phil Kaufman. Like Peckinpah, he had served as a Marine and was a heavy drinker. He was also a versatile actor who possessed a kind of greasy, anti-glamour: he expressed surprise at his frequent appearances in westerns, ’because my image of the western man is John Wayne and I’m just a little shit’ (quoted in Neumaier 2004). The critic David Thomson is an Oates fan, writing about him in 1981, the year the actor died:

Oates seems at first sight grubby, balding, and unshaven. You can smell whiskey and sweat on him, along with that mixture of bad beds and fallen women. He’s toothy, he’s small, he’s 53 this year, and he has a face like prison bread, with eyes that have known too much solitary confinement. (2002b: 642)

Thomson’s fellow critic, Michael Sragow, was another admirer, suggesting that the actor could:

Glower, furrow his brow and pull in his lip as skilfully as Fred Astaire could dance and Cary Grant could grin … Even in an age of easy riders and easy pieces, Oates’ confusion had special resonance. His scowl, which could suggest anything from bereavement to amusement, most often signalled a mixture of anger, befuddlement and defeat in the midst of a modern world that was passing beyond any individual’s power of understanding. (2000a)

In the documentary feature Warren Oates: Across the Border (Tom Thurman, 1993), actor Ned Beatty, is almost euphemistic, describing Oates as playing ‘negative’ guys, while Robert Culp calls him ‘a glorious failure that demands our love and respect’. Director Richard Linklater was unequivocal in his appreciation when he wrote ‘there was once a god who walked the earth named Warren Oates’ (2008). Alfredo Garcia was one of only three leading roles Oates played, out of the fifty or so films he made. Oates said of Peckinpah, ‘I don’t think he’s a horrible maniac; it’s just that he injures your innocence and you get pissed off about it’ (quoted in Thomson 2002b: 642). He openly acknowledged the director’s influence on his performance as Bennie: ‘I tried to say it all: what I knew about Sam and his love for Mexico. I really tried to do Sam Peckinpah: as much as I know about him, his mannerisms and everything he did’ (in Bomar and Warren 1981). This stretched to wearing Peckinpah’s sunglasses. Placing Oates in the role of surrogate-Sam makes it explicit that the self-pity and disgust that runs through the film is that of the director and what we see in the film is one drunken loser in sunglasses, chasing hopeless dreams of success south of the border, making a film about another drunken loser in (the same pair of) sunglasses.

Peckinpah reportedly auditioned a number of actors for the role of Elita before casting Isela Vega. She had been a model and singer before becoming an actor, appearing in many Mexican movies, including the evocatively-titled Cuernos debajo de la cama/Cuckolded Under the Bed (Ismael Rodriguez, 1969), Las luchardoras contra el robot asesino/Wrestling Women versus the Murderous Robot (René Cardona, 1969) and El Sabor de la Vengenza/Taste of the Savage/ (Alberto Mariscal, 1971). She pulls off the difficult role of Elita, a sexy, frequently topless singer/whore who both loves and betrays Bennie. She also wrote ‘Bennie’s Song’, which she performs on their fateful car journey. Two years after Alfredo Garcia, she was reunited with Oates in Drum (Steve Carver, 1976), the sequel to Mandingo (Richard Fleischer, 1975). She went on to write and direct the occult thriller, Los Amantes del senor de la noche/Lovers of the Lord of the Night (1986), starring alongside Emilio ‘El Indio’ Fernandez.

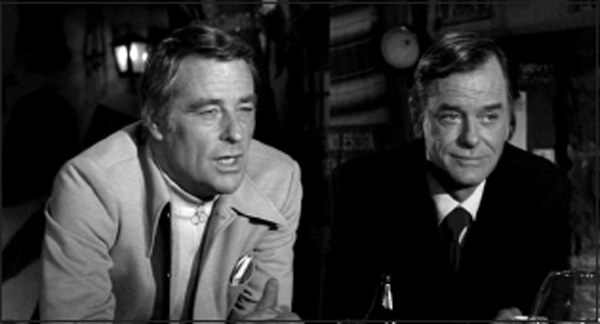

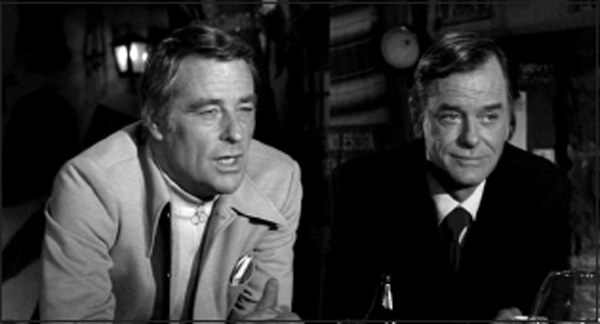

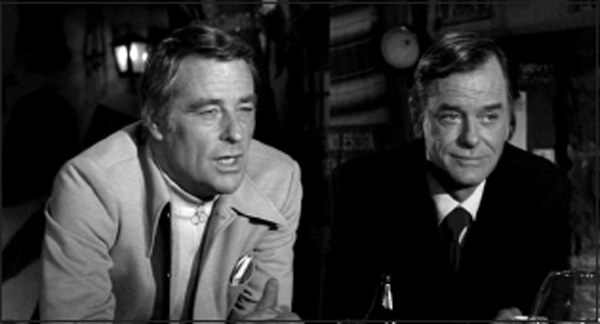

Fernandez was cast as the brutal patriarch, El Jefe. He was a frequent Peckinpah collaborator, notably in the role of Mapache in The Wild Bunch. ‘El Indio’ is a towering figure in Mexican cinema, a larger-than-life character onscreen and off. In the 1920s, he escaped from prison while serving a twenty-year stretch for his role in the Heurista rebellion. As an actor, he worked for John Huston (Night of the Iguana (1964)) and Polanski (Pirates (1986)) and co-starred with John Wayne (Chisum (Andrew McLaglen, 1970)) and Marlon Brando (The Appaloosa (Sydney J. Furie, 1966)). He was also a noted screenwriter and the director of 43 films, including Maria Candelaria (1944), which won the Grand Prize at Cannes in 1946. Fernandez was the subject of a number of rumours, such as the claim that he was the model for the Oscar statuette (see Ostrand 2006) and that he shot a critic in the balls. Two years after Alfredo Garcia, he was convicted of manslaughter after killing a farm labourer. Given this reputation, it is no surprise that people found Fernandez frightening. Peckinpah’s assistant and on/off girlfriend Katy Haber called him ‘a poet, a writer, a director, a womaniser, a drinker and a murderer’ (in Fine 2005: 270) and Gordon Dawson wasn’t impressed: ‘He’d pistol whip people just to watch them bleed. Sam was not an evil man like this guy was’ (in ibid.). Robert Webber and Gig Young play the gay bounty-hunters who recruit and then double-cross Bennie. Although un-named in the film, in the script they sport the splendidly-Dickensian names Sappensly and Quill. Webber is probably best-known as Juror Number 12 in Twelve Angry Men (Sidney Lumet, 1957). Like Peckinpah and Oates, he had served in the Marines. A veteran character actor, he had appeared in Harper (Jack Smight, 1966), The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967) and a lot of television shows including The Outer Limits, Mission: Impossible (1966–73) and Kojak (1973–78). He had worked with Peckinpah years earlier, in an episode of The Rifleman.

Robert Webber and Gig Young as Sappensly and Quill

Born Byron Barr, Young was best known for supporting roles in lightweight fare, such as Young at Heart (Gordon Douglas, 1954) and That Touch of Mink (Delbert Mann, 1962). He excelled, however, in the untypical role of the desiccated MC in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (Sydney Pollack, 1969) and won a Supporting Actor Academy Award for the role. But by the 1970s, he was beset by myriad personal problems, including a debilitating drink problem: he was fired from his role as the Waco Kid in Blazing Saddles (Mel Brooks, 1974) due to a bad case of the shakes. Peckinpah cast Young when his original choice for the role, the satirical comedian Mort Sahl, dropped out. Four years after the film, in September 1978, a Washington Post profile called him ‘blithe as ever, a survivor [who] is frustrating the Curse of the Oscar’ (quoted in Anon. 1994). Less than a month later, Young was dead, shooting himself after killing his fifth wife of three weeks, 21-year-old actor Kim Schmidt. To the end, the actor was aware of the debt of gratitude he owed to Alfredo Garcia’s Martin Baum, who, as his agent, had lobbied tirelessly on his behalf. He bequeathed his Academy Award to Baum, who would go on to describe Young as seeming ‘like a man who had everything going for him. How little we know’ (quoted in Anon. 2004). It may be hindsight, but his dead-eyed performance in Peckinpah’s film is chilling, his eerie smile and hangdog face lined by alcohol and disappointment.

Helmut Dantine was cast as Max, a cold-blooded El Jefe crony. Dantine was an Austrian who came to America in the late 1930s after his anti-Nazi activities led to him spending three months in a concentration camp. He had an uncredited part in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) and, like many European refugees of the time, he often played Nazis (in Mrs Miniver (William Wyler, 1942) and Edge of Darkness (Lewis Milestone, 1943)). In addition to his acting duties, he was an executive producer on Alfredo Garcia and The Killer Elite and, in what was no doubt a bit of wish fulfilment on Peckinpah’s part, he is shot dead in both. Kris Kristofferson plays the Charles Mansonish biker who abducts Elita before being killed by Bennie. He had been a Rhodes scholar and a helicopter pilot in the US army before becoming a songwriter, working with artists including Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis. He went on to have a successful career as a singer/songwriter and is best known for the songs ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ and ‘Help Me Make It Through The Night’ (both 1969). After popping up in Dennis Hopper’s chaotic The Last Movie (1971), he starred as a singing drug-dealer in Cisco Pike (Bill L. Norton, 1972). Alfredo Garcia was his second Peckinpah film, following his turn as Billy the Kid in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. He went on to appear in the smash hit 1970s version of A Star is Born (Frank Pierson, 1976) before taking the lead in the shambolic Convoy (1978). Since then, in addition to his recording career, Kristofferson has featured in a number of interesting projects (Heaven’s Gate, Limbo (John Sayles, 1999), The Jacket (John Maybury, 2005)) as well as some shoddy commercial fare (alongside fellow Peckinpah veteran James Coburn in Payback (Brian Helgeland, 1999) and Planet of the Apes (Tim Burton, 2001)). In 1975, he recorded the song ‘Rocket to Stardom’ with Warren Oates providing backing vocals. Donnie Fritts played keyboards in Kristofferson’s band and he was cast as the other biker. He crops up in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Convoy, as well as Cockfighter (Monte Hellman, 1974) opposite Oates. Other Peckinpah cronies turn up, some in wordless cameos. Katy Haber, the actors Don Levy and Richard Bright and the director’s eldest daughter Sharon all make appearances.

CREW: PECK AND THE PACK

The cinematographer was the Mexican Alex Phillips Jr. His Russian father was ‘a legend of Mexican cinema’ (Davison 2007), a prolific cinematographer with 202 film credits, including Luis Buñuel’s Robinson Crusoe (1954). Phillips Jr was no slouch, either, working on more than one hundred films including Ralph Nelson’s weird western The Wrath of God (1972), George C. Scott’s overheated Oedipal drama The Savage is Loose (1974) and the box-office smash Romancing the Stone (Robert Zemeckis, 1984). His work on Alfredo Garcia is certainly distinctive, from the effectively scuzzy (the scenes in Bennie’s room at the start of the film) to the idyllic (the sunny drive through the countryside) to the awful, particularly the mismatched lighting after Bennie kills the bikers. In fact, much of the disorientation of the film’s first half comes from the way the lighting appears to change from shot to shot, offering the most dislocated cinematography in a studio film since Russ Meyer’s demented Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970). While Phil Davison considers that ‘the lens perfectly captures Peckinpah’s vision of an alcohol-induced feverish dream’ (2007), Richard T. Jameson and Kathleen Murphy’s (euphemistic?) description of the cinematography as ‘eerily poor’ (1981: 45) is nearer the mark.

The music was by the frequent Peckinpah collaborator Jerry Fielding, who worked with the director on six projects, starting with the television play Noon Wine (1966). Particularly noteworthy are his brooding, atmospheric scores for The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs. After an investigation by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Fielding had been blacklisted in Hollywood for much of the 1950s but made a high-profile comeback with his work on Advise and Consent (Otto Preminger, 1962). He would go on to score pictures for Karel Reisz (The Gambler (1974)), Donald Cammell (the cult sci-fi film Demon Seed (1977)) and Don Siegel (Escape from Alcatraz (1979)), as well as regular collaborations with Michael Winner and Clint Eastwood. Unsurprisingly, his relationship with Peckinpah did not always go smoothly: after Steve McQueen junked Fielding’s score for The Getaway, the composer turned down the chance to work with Bob Dylan on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. His music for Alfredo Garcia is magnificent, albeit strikingly odd: in places it is so over-emphatic, it almost comes across as parodic, ranging from lush string arrangements and horror movie discord via some fauxmariachi noodling. But this eclectic approach actually works in a film so stylistically excessive, with the music matching the artless framing and cluttered mise-en-scène perfectly. Particularly effective is the use of muzak in upmarket hotel scenes, tacky music for El Jefe’s tacky hoods. When Bennie opens fire, killing everyone in the room, the tinny, upbeat sounds serve as an ironic counterpoint, an idea later used by George Romero in his Dawn of the Dead (1978). Fielding died young (aged 58) of heart failure, as would Peckinpah (at 59) and Oates (53).

THE SHOOT, RELEASE AND INITIAL RECEPTION

Peckinpah shot the film in Mexico, in Mexico City and Cuernavaca. He had a long, ambivalent relationship to the country, and in his work it often seems to represent both a heaven and a hell, a site of innocence and a primitive place of violent death – a surrogate Vietnam, perhaps. He said of Alfredo Garcia, it ‘couldn’t have been made anywhere else’ (in Madsen 1974: 91) The shoot was a difficult one, although this wasn’t unusual for a Peckinpah film: on Major Dundee he had been attacked by a sabre-wielding Charlton Heston, fired 35 members of the crew on The Ballad of Cable Hogue, caught pneumonia after a Lands End drinking binge on Straw Dogs, pissed his name on the dailies of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and was often too out of it to work at all on Convoy. These kind of stunts led Garrett Chaffin-Quiray to suggest (slightly euphemistically) that Peckinpah used ‘a kind of out-of-control creative experience whereby directors harangue, terrorise and otherwise influence actors to give electric performances’ (2007: 282). During his intermittent periods off the booze, Peckinpah was smoking a lot of dope and spent much of his time in his trailer, hooked up to an IV drip.

When UA executives saw the film, they were horrified. Fearing it would earn a commercially disastrous X rating, they considered not releasing it at all. The previews were terrible. One ended with only ten viewers left in the cinema. The responses on the preview cards included ‘the most terrible movie I’ve ever seen’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 149), ‘to put that inhuman mess on film is a crime’ (quoted in ibid.), ‘this picture should be burned’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 227) and ‘it doesn’t relate to my life or anyone else’s’ (quoted in ibid.). The reviews were even worse. For the Wall Street Journal:

So grotesque in its basic conception, so sadistic in its imagery, so irrational in its plotting, so obscene in its effect, and so incompetent in its cinematic realisation that the only kind of analysis it really invites is psychoanalysis. (Quoted in Prince 1998: 195)

New York magazine called it ‘a catatastrophe’ (quoted in Ebert 2001); Variety wrote that it was ‘turgid melodrama at its worst’ (quoted in ibid.). Vincent Canby suggested that all of Peckinpah’s previous films should be reappraised in the light of this ‘disaster’ (1974). For the New York Times, it was ‘a film portrait of pessimism’ with Oates ‘blustery … frantic’, Vega ‘awkward’, Young, Kristofferson and Dantine ‘wasted in roles that give them little chance to act. But the movie’s main problem is that the protagonist – the dead head – is a bore’ (Sayre 1974). One outraged critic even called it ‘the greatest film of the thirteenth century’ (quoted in Schager 2005). In America, only Jay Cocks and Roger Ebert defended the film. The former considered it ‘full of fury and bile … a troubling, idiosyncratic and finally unsuccessful film’ (1974). Cocks also suggested that it may be a self-mocking provocation to the director’s many critics, a theory explored in-depth in chapter 3. Ebert, one of the first to praise The Wild Bunch, called it ‘some sort of bizarre masterpiece’ and observed that Peckinpah was ‘asking us to somehow see past the horror and the blood to the sad poem he’s trying to write about the human condition’ (2001). The film fared slightly better with critics in the UK. It got a positive review in the Monthly Film Bulletin in 1975 (see Thomson 2009) while Chris Petit in Time Out praised the film, albeit in a manner that served to warn the unwary:

There’s no suspense; what happens is as predictable as it is inevitable. Peckinpah has structured a slow, almost meditative film out of carefully fashioned images that weave inextricable links between sex, death, music and violence. (1998: 28–9)

Richard Combs in Sight & Sound called it ‘savagely succesful’ (1975: 121) but for Derek Elley in Films and Filming ‘Peckinpah’s grasp of the situation falters as the slow-motion increases … Warren Oates, sad to say, is not yet capable of carrying an entire film … the play with brutality and profanity appears merely childish’ (1975: 35). Looking back on the occasion of the film’s re-release, the Observer’s Philip French recalled how his initial description of the film as ‘a combination of Jacobean revenge tragedy, classical quest myth and political fable’ that takes place in ‘an emblematic Mexico that Lowry, Greene, Lawrence and Traven would recognise’ (2009) earned him a place in Private Eye magazine’s Pseud’s Corner.

The film bombed at the box office. It was banned in Sweden and Argentina. UA took out adverts a quarter of the usual size. But marketing a film about a man, a woman and a severed head was always going to present problems. The North American promotional campaign made it look like another thriller in the mould of The Getaway. The poster emphasised the violence (with images of bodies falling and Bennie’s gun) and Vega’s sex appeal (an image of her with her dress hanging off), with the tag-line: ‘Was one man’s life worth 1 million dollars and the death of 21 men?’ For the European release, the marketing made more of the Peckinpah brand name: both the West German and the French posters have the director’s name prominently positioned. While the German one uses a familiar image of an unwashed hand clutching the locket containing Al’s photo (an image used for US re-releases and on the R1 and R2 DVD sleeves), the French poster is much more striking: a yellow faux-Wanted poster, bearing an image of a bloodied Oates and the memorable tag-line: ‘attention! cet homme est dangereux il recherche une tete’ (‘attention! this man is dangerous, he searches for a head’). The weirdest promotional campaign was that used in Turkey, where the poster shows an illustrated, muscle-bound man who looks nothing like Oates, bursting out of his shirt like the Hulk. He stands astride a decapitated body, holding a bloody machete in one hand and a bleeding severed head in the other, while a woman wearing only a thong lounges decorously in the background.

How do you market a film about a man, a woman and a severed head?

Steven Prince relates a story that demonstrates Peckinpah’s fruitless attempts to emphasise the love story in the promotion of his film:

[Peckinpah] wrote to producer Helmut Dantine that the trailer looked good, but added, ‘We should cut down the final shoot-out, in order to accentuate the love theme a little more’. (1998: 149)

One only has to see the trailer to see that Peckinpah didn’t get his wish. The emphasis is firmly on action and the anticipation of violence, from Bennie buying his machete and standing in the grave to Quill firing his machine gun, an incredible amount of shooting and slow-motion death.

The trailer’s voice-over reinforces this, while also emphasising an unusually strong authorial connection:

[Over a shot of Bennie, wearing shades] This man will become an animal.

[Elita in the shower and being stripped by the biker] This woman’s dreams of love will be destroyed.

Innocent people will suffer. 25 people will die. All because of Alfredo Garcia and only one man really knows why. Sam Peckinpah.

His career never really recovered. Peckinpah had used up all of the critical kudos he had earned with The Wild Bunch and although he would have commercial hits (such as The Killer Elite) and some good reviews (for Cross of Iron), he was in a downward spiral both professionally and personally. Between 1975 and his death in 1984, there was cocaine, paranoia, a heart attack and a couple of videos for Julian Lennon (‘Do you know’, he said to his second wife, Begonia Palacios, days before his death, ‘the last film I made was five minutes long?’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 376)). But he remained defiantly proud of Alfredo Garcia. When asked, late in life, whether he harboured any desires to make a ‘pure Peckinpah’, he answered ‘I did Alfredo Garcia and did it exactly the way I wanted to. Good or bad, like it or not. That was my film’ (Weddle 1994: 497).