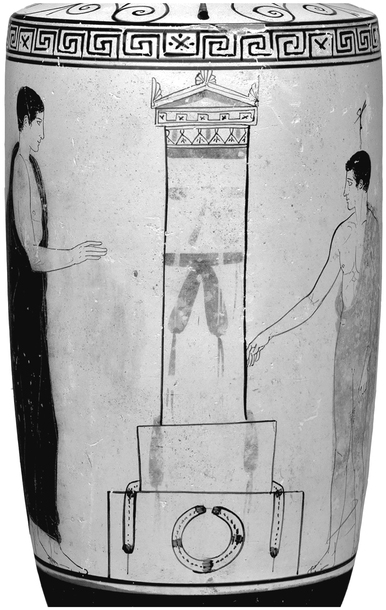

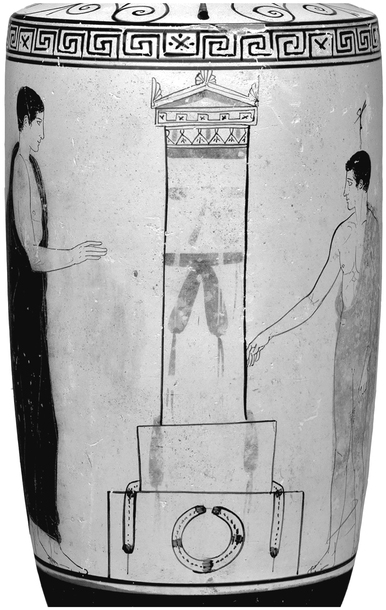

Figure 1.1 Achilles Painter, ca. 440 BC, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.281.72

Interactions between the living and the dead on white-ground lêkythoi

Molly Evangeline Allen

Before the Classical period, Greek image and text were consistent in their portrayal of the deceased as a passive entity that was at the mercy of the living in gaining passage to the Underworld and, thus, integration into the afterlife. Although the details of the afterlife, as they appear in extant image and text, are hazy, there is an overwhelming sense that one should do everything in their power to help the dead gain access to it. Thus, Patroclus’ shade implores Achilles to think not only of his own sorrow but to turn his attention to quickly preparing his corpse for burial (Iliad, 23.69–92) and Elpenor hastens to meet Odysseus at the outset of his katabasis to beg him to not leave him unburied and unwept (Odyssey, 11.51–78). In each instance, the deceased man has been left in an uncomfortable, liminal stage between life and death due to their not being buried. So integral to being accepted into the Underworld was the proper handling of the corpse and its subsequent burial that the image of an extravagant, well-attended funeral came to symbolize the successful integration of the dead into the afterlife (see below for more on the use of this image in Geometric and Archaic funerary art). A change in popular funerary imagery in Attic vase painting around the first quarter of the 5th century BCE, from focusing on the funeral to focusing on the indefinite upkeep of the grave and the cult of the dead, suggests a growing interest in the ongoing experience and well-being of the deceased. From images that show mourners interacting at the grave, with or without the presence of the dead explicitly depicted, one gets a sense that the Greeks believed themselves capable of affecting the souls beyond the grave. By looking at just a few details of the imagery of white-ground lêkythoi, the favoured funerary vessel of 5th century Athens, we can begin to better understand what the Classical Athenians imagined the afterlife entailed and how it affected their day to day lives.

There is no single source that provides a satisfying description of what one might expect in the Greek afterlife, though it is clear that arriving in Hades/the Underworld was a prerequisite for a restful afterlife. The landscape of the Underworld and the typical activity of the souls within it is briefly alluded to in a handful of Greek texts, most notably the Odyssey (esp. books 10, 11, and 24) and Hesiod’s Theogony (726ff.) but for the most part individuals were left to imagine it in their own way. The Underworld was often described as a shadowy place that was encompassed by Oceanos, intersected by the Styx and a number of other marshy rivers, and shaded by thick groves of dark trees (for sources see Garland, 2001, pp. 49–52, 149–152, and Johnston, 1999, pp. 15–16). Its dark and foreboding physical features befit a place that cannot ever be investigated or understood and that lies deep below the earth’s surface. Since Hades was ultimately impenetrable by the living, with only rare mythological exceptions breaking this rule (e.g. Odysseus, Heracles, and Orpheus), and inescapable by the deceased (ghosts and other haunting souls belong to a category of restless dead, who had not been accepted into the Underworld (cf. Johnston, 1999, pp. 77–79)), it is perhaps no surprise that the ancient Athenians generally avoided portraying its physical aspects. Interest in chthonic geography grew by the end of the 5th century, notably in the work of Euripides, Aristophanes and Plato, but in general, discussions of its landscape were restricted to the initiates of clandestine mystery cults and were not meant for public consumption in vocal, written or visual form. The growing popularity of mystery cults that purported to have inside knowledge about the Underworld points to a growing anxiety and/or interest in the unknown frontier that awaited all Greeks at the moment of their death. Even Heracles, in an apparent attempt to better inform himself about, and protect himself from, unknown dangers of the Underworld, desired to be initiated in the Eleusinian Mysteries before his descent to retrieve the watchdog of Hades, Cerberus, (Apollodorus 2.5.12; Diodorus Siculus 4.25.1; Euripides, Hercules Furens 610-613). Not much is said about how souls were thought to pass their time in eternity, but from what little anecdotal evidence there is, it seems that one might hope to reunite with lost loved ones, tell stories, gossip with friends and family, and engage in pastimes once enjoyed in the living world (Garland, 2001, pp. 66–74).

The primary place in which the details of the Greek Underworld were revealed is through mythological katabases, such as those of Odysseus, Orpheus and Heracles. However, these katabases, as well as other chthonic myths, were rarely depicted in the visual arts, and the relationship between the living and the dead was of more interest to Athenian vase painters than the afterlife per se. Pausanias (10.25–28) attests that Polygnotos’ painting of Odysseus’ katabasis on the walls of the Lesche of the Cnidians in Delphi captured the damp, shadowy ambience of Hades in an apt and admirable manner, consistent with its character in epic poetry. Heracles’ abduction of Cerberus appears in a handful of black- and red-figure vases (e.g. LIMC V, Herakles 2602–2604, 2614) and there is a meager collection of images that portray the punishment of Sisyphus (e.g. LIMC VII, Sisyphos I 6), but there is only one extant vase depiction of Odysseus in the Underworld (ARV2 1045.2, Para 444).1 In this exceptional vase by the Lycaon Painter (Boston, MFA, 34.79), we find Elpenor emerging from behind rocks and a thicket of reeds. He approaches a contemplative Odysseus who, on the advice of Teiresias, has sacrificed two sheep so that their blood, offered as a libation, will allow souls to speak. Anyone familiar with Odysseus’ katabasis would remember that Elpenor approaches Odysseus at this moment to describe to him the discomfort he is in as a consequence of being left unburied (Odyssey 11.51–78). His plight reminds us of the importance of burial for a restful afterlife.

Despite a general uncertainty about the afterlife in text and image, descriptions of how the soul left the body and began its transition from the world of the living to the world of the dead were fairly prevalent and consistent in epic and mythological narratives. Thus, in Homer (e.g. Iliad 16.453, 856–858 and Odyssey 11. 220–224) we find that when the body relaxes in death, the soul (psychē or eidōlon) is released and awaits the deposition of its corporeal body so that it may enter the afterlife (Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, pp. 56–60). Though the soul is mobile and lively at the moment that it leaves the body, generally speaking in the world of Homeric epic the dead are witless and incapable of influencing the living (Heath, 2005, p. 380). So, it is not so much fear that compels friends and family to bury the dead but a sense of duty and an earnest desire to send souls to rest. In the visual world, prior to the 5th century BCE the dead are almost always depicted as helpless corpses, which is consistent with the idea that, once dead, a person was entirely at the mercy of the living when it came to their eternal restfulness. A few images of the restless soul of Patroclus accompanying the dragging of Hector’s body are the only noticeable exception to this rule and in this instance, the soul of Patroclus is present and mobile precisely because he has not yet been buried and he has been left to roam aimlessly at the mercy of Achilles’ goodwill (e.g. LIMC III, Automedon 16, 21, 28). Achilles’ delay in burying Patroclus is a significant issue in the narrative of the Iliad and the presence of his soul in these scenes serves to underscore Achilles’ less than heroic tendencies. When the deceased are represented by their corpses in prothesis scenes, this represents a moment at which they have not yet been integrated into the afterlife, but they are well on their way.

The anguish of being left unburied, and hence left in a liminal space between the Upper- and Underworlds, played a central role in a number of ancient Greek myths, which demonstrates the centrality of burial to achieving a happy afterlife. Thus, Patroclus’ shade pleads with Achilles in the Iliad (23.69–76) not to leave him unburied; Antigone stops at nothing, despite Creon’s orders, to provide at least a semblance of burial for her brother, Polynices (Sophocles, Antigone 26–46); and Electra consults with elder mourners about how to properly and effectively honour and appease her recently, but unconventionally, buried father (Aeschylus, Libation Bearers 84–166). While Patroclus’ and Polynices’ plights underline the importance of burial per se, Agamemnon’s fate, being both murdered and buried by a malevolent wife, shows that a soul may not rest easy if their death is violent and/or their burial distorted. Thus it seems that the correlation between proper burial and resting in peace was so strong that the prothesis easily became an intelligible and ideal representation of a happy afterlife.

Since a tradition of a hierarchical afterlife in which the actions of one’s life govern whether they will be punished or rewarded was not prevalent in Greece, one can presume that the dead that are depicted in prothesis scenes are on their way to a neutral, if not happy, afterlife (Garland, 2001, p. 74 and Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, p. 298). In other words, a typical Athenian did not run the risk of being tortured like the legendarily hubristic Tantalus, Sisyphus or Prometheus. However, by the 5th century BCE, there seems to have been growing anxiety about the influence of the dead and a concern that those who died unnaturally young (aôroi) or were murdered (biathanatoi) or were left unburied (ataphoi) would produce restless souls (Garland, 2001, pp. 77–103 and Johnston, 1999, pp. 71–86). There was not a separate afterlife for individuals in these categories, but their potential to be upset and possibly influence the world of the living provided greater impetus for the living to not only provide fitting burials, but to be vigilant and generous in their continued care for the cult of their deceased family members (see below).

So important was it for an individual to be granted access to the afterlife that it is no surprise that from an early point in time (at least from the 8th century BCE, the date of the earliest extant Greek textual and visual evidence) we find that access to the Underworld is intimately tied to the proper fulfilment of burial rites. Since the actions of the funeral were tailored to guarantee this access, the image of a prothesis was easily equated with acceptance into the Underworld; it was up to individuals, not artists, to imagine and construct the details of the afterlife that followed cremation or interment. By emphasizing the proper and timely carrying out of all prescribed stages of a funeral (kêdeia) as the primary means of gaining access to an afterlife, the onus is placed firmly and deliberately on the living and their care of the corpse. This provided a façade of control over a realm that was inherently uncontrollable. By all accounts, any good Greek took this duty very seriously as both a courtesy and an obligation to the dead and one which they hoped would be returned to them in kind. If a family had the means they might provide a more extravagant affair that would enhance the honour, reputation and memory of an individual, but even the simplest of burials was capable of providing entrance to the afterlife.

Thus, from the late 8th until the early 5th century BCE, the funerary image par excellence was the prothesis, the event during which the recently bathed and dressed corpse was laid out on a bier to be visited and mourned by the bereaved. The prothesis was one of the first subject matters to be illustrated in the earliest narrative scenes of Geometric art and was adapted to adorn the subject fields of Archaic black-figure pinakes and black- and red-figure loutrophoroi, phormiskoi and other vase types found in funerary contexts. Unlike other scenes or subject matters that came and went in and out of fashion or favour in Athenian vase painting, the prothesis scene remained popular for over 200 years. Due to its enduring popularity, its significance in reference to Greek art and Greek burial practices has been the focus of study for many scholars over the years (see esp. Ahlberg, 1971; Boardman, 1955; Oakley, 2004 and Shapiro, 1991). Although the prothesis was only the first of three stages of the funeral, which was followed by the ekphora (transportation of the corpse via processional to the grave) and ultimately the deposition of the body, it came to symbolize the entire ceremony and, by extension, the successful transition of the deceased from the Upper- to the Underworld. At the prothesis, mourners surrounded the corpse to offer final songs and tears and to steal final embraces and last looks at the deceased. Since the prothesis scene takes place prior to burial, it represents a period of time during which the soul has not been fully accepted into the afterlife. Thus, when viewing an image of a prothesis, we are viewing a moment when the greatest concern of the bereaved is how their actions (both preparing the body and lamenting the loss) may affect the ability of the deceased to be fully integrated into the afterlife. There is no explicit visual link to the afterlife, but understanding the significance of the ceremony, we understand that this was likely a concern of the mourners. Most prothesis scenes crowd the narrative space with throngs of mourners, and thus visualize the broad impact that a person’s death has on family and/or community through the quantity of people shown to be affected by their passing. By showing large groups of mourners, an artist could heighten the gravity of the sense of loss and could provide a more honourable tribute to the vase’s recipient. The large crowds of people suggest that great care and concern was put into the funeral and it is easy to imagine that, as such, this body will have no trouble in transitioning to the afterlife.

The popularity of the prothesis scene was disrupted when a new vase, the white-ground lêkythos, was abruptly and broadly adopted as the favoured funerary vase in Athens, ca. 480 BCE, and brought with it a series of new scene types. During the course of the 5th century BCE, the white-ground lêkythos became the most popular vessel for depicting funerary scenes and are found ubiquitously in Classical Athenian burial contexts. The lêkythos, a vase for storing and decanting aromatic oils, had been produced in Athens since the beginning of the 6th century BCE (see esp. Oakley, 2004, pp. 5–8 and van de Put, 2011, p. 39) and, from archaeo logical evidence, we know that it had become the most frequently deposited object in Athenian graves by 560 BCE (Houby-Nielsen, 1995, p. 155). The white-ground variety of this vase was specifically used in a funerary context. It was buried with the dead and, likely, offered at the grave at indefinite points thence forth (cf. Arrington, 2015, pp. 240–74; Oakley, 2004, pp. 9–11 and van de Put, 2011, p. 143). Unlike other Athenian wares that were widely exported or imitated throughout the Greek world, these vases were almost exclusively created for an Athenian audience.

The precise reason for the great popularity of white-ground lêkythoi and implications of their use is beyond the scope of this paper. It will suffice to say that the effects of the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, as well as the great plague of 430-428 BCE, influenced changes in funerary practice in Athens, not least because they led to a sharp increase in the number of annual casualties. For practical and emotional reasons, especially since many soldiers died far from home, these events likely had an impact on the way that Athenians desired and were able to provide fitting burials for their family members. Public funerals honoured the war dead in a glorious fashion and helped to reinforce the civic ideals of Athens’ burgeoning democracy but they robbed families of the control they once had over the burial rites of their kin (Arrington, 2015, passim). In part as a response to the fact that the prothesis was no longer always in the hands of individual families, it is probable that the grave came to have significance as the place at which the Athenian people had the most control and influence upon the afterlife of their loved ones.

Although the graveside scene would come to be the most popular funerary scene of the 5th century BCE (see below), scenes that illustrated the deceased soul being led by a psychopomp, Hermes or Hypnos and Thanatos, to the Underworld (with or without the image of Charon standing by to ferry them across the Styx), were also fairly popular (Oakley, 2004, figs. 67–74). These images presuppose that the deceased has been provided a burial and they are well on their way to Hades, and thus bridge the gap between scenes at the funeral and scenes at the grave. Perhaps as a means of reassuring the living that this journey, though mysterious and dark, was not dreadful, the psychopompoi and Charon are regularly shown as kindly figures. Charon, as he appears in white-ground lêkythoi, is at times a bit gruff but unlike his Etruscan counterpart, Charun, he is not frightening (Garland, 2001, p. 56). The significance of the images of Charon transporting the dead to the afterlife in white-ground scenes has been studied in depth by Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood (1996, pp. 303–361), who argues that these images are reflective of a shifting attitude amongst the Athenians regarding their own deaths. She suggests that these images are consistent with an overall rejection of the Homeric tradition of a senseless, inert soul and a growing belief in more active and affecting souls. Such images reflect a growing sense of anxiety about one’s own death and the volatility of the dead and their potential to influence the world of the living.

These images do not depict the afterlife, but they do bring us to the brink of Hades and perhaps reflect a growing interest in the mystery of the hereafter. For the first time, ordinary Athenians are shown being ushered by mythological figures, and for the first time, the deceased is not represented by their corporeal body but by their soul, the only aspect of their being that persists after death. There are two main ways in which the soul is depicted in white-ground imagery: as small, winged silhouettes (psychai) and as figures that are visually indistinguishable from the living (eidôla). Together, these two forms visually represent two aspects of the soul as it is described and named in Homer. The soul (psychē) is often described as exiting the body in flight or like smoke (e.g. Iliad 9.408–409, 23.100–101), but it is also described as looking identical to its living counterpart, and is thus sometimes called an eidōlon, or ‘likeness’. Sourvinou-Inwood (1996, pp. 56–59) points out that ‘eidōlon’ and ‘psychē’ are often used interchangeably and sometimes in conjunction with each other. Similarly, the two means of depicting the soul could be used together, as is the case for the deceased youth shown in Figure 1.1, or separately to represent a single decedent. In Homer, the eidōlon appears as such a convincing likeness of its living self that both Achilles and Odysseus, when faced with the souls of Patroclus and Anticleia respectively, are compelled to hug them as if they were alive and capable of offering such an embrace (Iliad 23.99–101 and Odyssey 11.204–224). In white-ground imagery the eidōlon is often only distinguishable from its living counterparts by its dress, or lack thereof, and behaviour. For example, while the living are shown mourning and making offerings at the grave, the deceased are static, seemingly disinterested in the grave or others around them, and do not partake in typical mourning gestures or activities (Closterman, 2014, pp. 91–92 and Oakley, 2004, p. 151). As opposed to earlier vase imagery where the dead is most frequently shown as a corpse, by far the most popular way of depicting the

Figure 1.1 Achilles Painter, ca. 440 BC, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.281.72

dead on white-ground lêkythoi is as an eidōlon, either standing beside their grave or being led to the Underworld by psychopompoi. Images of the soul being ushered to Hades do not provide a sense of how the souls interact within the afterlife, but they provide a rare glimpse into how Athenians imagined the soul continued its journey once free from a corpse.

By the middle of the 5th century BCE, the graveside scene was by and large the most popular (Giudice, 2015, Kurtz, 1975, Oakley, 2004 and Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, pp. 324–327). The earliest extant graveside scene appears on an early 5th century black-figure loutrophoros by the Sappho Painter (Athens, NM 450 (cf. ABL, 229.59, Kurtz and Boardman, 1971 pl. 36)) but it is exceptional for its time and genre. Like the images that appear on white-ground lêkythoi, this vase depicts two mourners flanking a simple grave. In this example, the women are posed with their arms outraised in tell-tale gestures of grief that are used by female mourners in most prothesis scenes (see esp. Huber, 2001 and van Wees, 1998). Women in graveside scenes on white-ground lêkythoi occasionally appear enacting the same gestures but often artists trade these gestures for poses associated with dedicating gifts upon the grave. It should be noted that the painters of this new genre of funerary vase did not reject prothesis scenes altogether, but rather they were quick to embrace a new context for demonstrating the relationship between living and dead Athenians.

In and of itself, a shift from images of the funeral to images of the grave shows a shift in interest from the care and concern invested in simply ensuring passage to the afterlife through the initial funerary rites toward an interest in providing continual care so that the integrated soul would be content. These images show that the burden of caring for the dead did not end the moment that a corpse was cremated or interred, but continued indefinitely. The impetus to care continuously for the dead must have been stimulated by a few factors, but most importantly by an individual’s desire to care for their loved ones to their best ability. Since the focus moves from a single moment of impact (the prothesis) toward indefinite obligation to the dead (visiting the grave at any point after burial), we may also conclude that the Athenians believed that they were capable of affecting one another beyond the grave. A brief overview of the development of graveside scenes suggests that consideration for one’s family in the Underworld was ongoing and could affect one’s day-to-day life. As these scenes changed and developed over time, we get the impression that consideration of the afterlife remained a constant concern, and that the souls of the dead were perceived more and more to be potentially volatile and equally capable of affecting the Upperworld (Garland, 2001, p. 134 and Johnston, 1999, pp. 71–86).

While the deceased had inevitably been depicted by their corpse in pre-Classical Athenian funerary imagery, in graveside scenes the deceased was represented by a sepulchral stêlê or mound and, by the third quarter of the 5th century BCE, often additionally by a lifelike representation of their shade, soul or ghost (as described above). In the most basic graveside scenes, one or two mourners approach a simple grave marker bearing gifts to dedicate ritually at the grave. Like a corpse, the grave monument, often referred to as a sēma, ‘sign’, or mnêma, ‘memory’ (cf. Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, pp. 140–145), is an inanimate represent ation of the dead, capable of receiving gifts and honour but incapable of self-expression or reciprocation. However, unlike the corpse, the grave came to be an important symbol of communication between the Upper- and Underworlds, and provides a certain and indefinite point of contact between the two. Thus, the interest of artists in depicting the relationship between the living and the dead comes to take a slightly different form.

Grave markers provide a lasting visual representation of the deceased and were the agreed upon points of contact between the living and the dead. In Athens, grave markers took many different forms between the Geometric and Hellenistic periods, from simple stones, used merely to indicate the place of one’s burial, to towering and expensive vases, statues and stêlai that were conspicuous representations of the wealth, honour and/or virtues of the dead and their family (cf. esp. Kurtz and Boardman, 1971, passim; Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, pp. 109-139 and Vlachou, 2012, pp. 367–375). From archaeological and textual evidence, it is clear that by dedicating gifts and speaking words of grief or praise in proximity to a grave, a mourner could effectively direct their offerings to a particular decedent. This point is illustrated by a few textual examples. The necromancy of Darius must take place precisely at the Persian king’s grave (Aeschylus, Persians 623–693); Electra is concerned about her behaviour and words spoken near her father’s grave lest she inadvertently upset his soul (Aeschylus, Libation Bearers 84–166), and many funerary epigrams invite passersby to speak, or be silent, depending on the particular desire or demands of each soul (cf. Paton, 1953, passim). There is a perceived sensitivity at the grave, as though it is the place at which the membrane between the two worlds is at its thinnest. This permeability is what permitted the living and the dead to interact despite their separation, and it underlines the importance of acting and speaking appropriately when in the presence of the grave. This would seem to indicate that the posture and activity of grave visitors in vase imagery is deliberate, appropriate, and effective. Proper behaviour at the prothesis was important for allowing the dead to reach the Underworld, but continued proper behaviour leads to a content soul and, depending on the perceived ability of the dead to affect the living world, protection from ill-willed spirits.

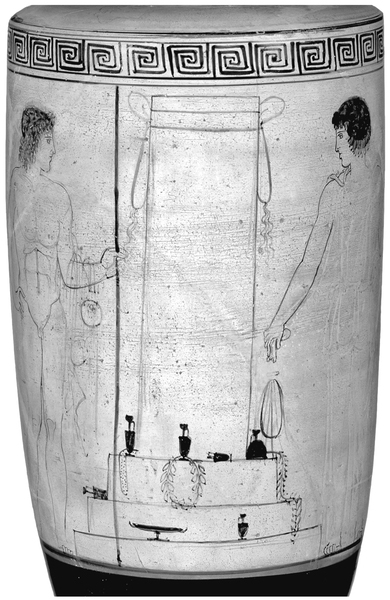

Since it was perceived that the grave was the point at which verbal communication and material goods might easily pass from the living to the dead, the particular gifts that are placed there reflect what Classical Athenians presumed the dead might need or want. Visual, textual and archaeological evidence shows that there was a broad range of items that a mourner might offer including libations, food, vases, locks of hair, textiles, ribbons, wreaths, animals, weapons, instruments, toys and other domestic objects (see Closterman, 2014, passim; Garland, 2001, pp. 104–118; Hame, 1999, especially pp. 118–120, 159–160; and Johnston, 1999, pp. 41–43). Food and drink were meant to nourish the soul, while instruments or sports equipment might provide entertainment, and expensive or ornate gifts could be appreciated as tokens of the love and loss felt by the bereaved. In a selection of scenes from tragedy (e.g. Aeschylus, Persians 607–618, Euripides, Electra 509–517, Orestes 1320–1321 and Sophocles Electra 893–901), visitors to the grave provide both consumable and decorative gifts, though the majority of evidence for the types of gifts offered comes from white-ground imagery. It is common to find images where visitors to the grave only bring one of these objects to a humbly decorated grave, but a few scenes demonstrate the versatility of the grave as a receptacle for gifts of every sort. Thus, in Figure 1.2 we find a woman approaching a stêlê with a large alabastron suspended from her right hand and a basket full of wreaths, garlands, and fruits. In this particular scene, we find that previously dedicated vases, wreaths, garlands and ribbons that decorate the tomb act as testaments to the vigilance of the bereaved family members, and act as visual indications that this grave has been visited frequently over time.

Gifts dedicated at a grave were intended to be received by the deceased, even if not every mourner believed that they were actually used or consumed by them, and hence acted as a form of communication between the living and the dead. At the same time, in as much as they were visible to any visitor to the cemetery, they were also a form of communication between mourner and community (Closterman, 2014, pp. 89–90). What gifts ought to be offered and how each was to be accepted or appreciated undoubtedly depended on the intention and interpretation of each gift giver (Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, p. 46). For the most part, it was likely goodwill and genuine concern for the dead that inspired the types of gifts offered. However, the details from one of the few surviving, ancient Greek ghost stories, related by Herodotus (5.92), suggests another motivation for providing specific gifts to the dead. Herodotus claims that the Corinthian tyrant Periander, sought aid from the ghost of his wife Melissa, whom he had killed (Herodotus 3.50), but that she refused to aid him because she was naked and cold because he had improperly cremated her. In order to appease her spirit, he ultimately offered her befitting clothes by burning them in a pit and as a result she agreed to help him. This anecdote suggests that negligence towards the care of the corpse could create restless or even spiteful souls, but it also suggests that one could remedy their folly by offering appropriate gifts at a later time.

As it was a mark of good character if one cared for their deceased relatives, a grave that was well looked after helped to confirm the standing of individuals and families within the Athenian community. One could confirm or reaffirm their place in the community by demonstrating their ability to maintain the graves of their ancestors, which in turn proved their belief in a shared understanding of the afterlife. Caring for the graves of one’s family members was so crucial that it could be used as evidence of kinship in matters of inheritance (e.g. Isaeus, Philoctemon 65) and an unkempt grave might testify to the disregard that someone had toward the well-being of their deceased family members. Anxiety that one would go unburied or that their grave would be neglected was incentive for showing kindness towards others’ graves and in at least one incidence was used as grounds for adopting heirs (Isaeus, Menecles 10). Evidence of sumptuary laws meant to control public displays of wealth at the funeral and grave indicate that there was a perceived need to officially curb the ostentatiousness of funerals and

Figure 1.2 Bosanquet Painter, ca. 440–430 BC, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 23.160.38

the displays of wealth associated with the graves of the elite (Blok, 2006 has collated the textual evidence). Thus, care for the dead held great importance to 5th century Athenians and it needed to be done in a thoughtful yet appropriate manner.

In addition to being an important point of contact between the living and the dead, the grave was also, ultimately, the most conspicuous reminder of the great distance between them. Theoretically, a trip to a grave allowed a mourner to be nearer to a lost loved one, but when confronted by a lifeless grave marker the magnitude of their true separation might come to the forefront of their mind. The grave was simultaneously representative of a lasting connection to the dead, but also of the permanence and alienation of death. In lieu of a body, the grave marker provided a physical object that the bereaved could direct their attention towards, and it allowed them to enact particular rites and rituals that necessitate a physical body. Hence, a stêlê could be ‘dressed’ in ribbons, wreaths or textiles and could be anointed with oils and even embraced (much as the corpse had been during the funeral), which is what we find mourners doing in many of the grave visit scenes on white-ground lêkythoi (cf. Oakley, 2004, figs 118, 125, 155 and plate VIIA-B). Our primary evidence for engagement of this type between mourner and stêlê is vase imagery and there is little to no written testimony regarding the origin and function of each specific type of adornment (see Garland, 2001, pp. 115–118, 170–171). The love and kindness offered to the grave was not returned in kind, but the belief that one’s concern directed toward it would be understood and accepted by the intended recipient must have offered enough pleasure and reassurance to compel Athenians to be vigilant in their attention and upkeep of familial graves.

As the graveside scene grew in popularity and artists continued to explore its potential to express the solemnity of death along with the care and concern of the living and the honour and memory of the dead, it became increasingly common to find images that incorporated both living and deceased visitors. Since the grave was, on its own, capable of representing the deceased, the choice to include a representation of the soul was deliberate and pointed. As mentioned above, the deceased soul could be depicted in two distinct ways: a small, winged psychē or a lifelike eidōlon. The diminutive version of the soul is found quite infrequently in graveside scenes and is usually coupled with an eidōlon, as can be seen in Figure 1.1. In an image such as this, it is possible that the small winged soul is meant to visually identify the figure above which it hovers as deceased. It is also possible that it is merely meant to show the multiple facets of the soul. More often than not, the deceased soul was visually indistinguishable from its living counterparts and there is unfortunately no single means of determining whether a figure that appears beside the grave is living or dead (Arrington, 2015, passim; Garland, 2001; Kurtz, 1975, pp. 223–224; Oakley, 2004, pp. 164–173; and Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, pp. 324–325). There is no definitive consensus as to whether we are meant to understand these figures as ghosts, souls or simply figments of the imagination of living visitors to the grave (cf. Arrington, 2014, passim and Oakley, 2004, pp. 165–166). Although understanding their true nature would help us to better understand the complexity of the relationship between the various figures in these scenes, we can still appreciate that these images show a certain unity and dependency between the living and the dead. Independent of what they are meant to be, they represent the dead and they serve the function of providing a visual recipient for the offerings presented at the grave (Arrington, 2014, passim and Oakley, 2014, pp. 166–167).

That being said, there are a few visual clues that we can use to determine the vitality of each character in these scenes. Although deceased souls look like the living, they can often be identified as ‘not living’ by their dress, or lack thereof, and/or by their behaviour. Since it would presumably have been out of the question to visit the grave nude or wearing armour, these are visual indications that the individual is not a living visitor at the grave (Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, p. 324 n. 99). The reason to illustrate an Athenian man nude, in armour, and/or carrying weapons or athletic gear was to highlight his strength and virtue, which makes this a great way to depict, and thereby glorify, a deceased figure, but a strange way to show someone simply engaged in a mundane activity such as tending to a grave. Unlike living visitors, the deceased does not typically bear gifts and rarely engages with other figures or objects in the scene. Instead, they often appear static and seem to function primarily as visual representations of the intended recipients of grave offerings. Occasionally, a deceased figure will appear seated upon or near the grave marker, and their proximity to the grave visually indicates their relationship to it. More typically, the living and dead visitors stand on opposite sides of the grave marker, explicitly reminding us of the well-defined and unwavering boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead; a boundary that might be transgressed in tragedy and myth, but not in the ordinary world. They are connected via the stone, but equally divided by it. When sculpted grave stêlai became popular in the late Classical period, one of the most common motifs was the dexiosis, or ‘handshake’, which seems to emphasize the role of the grave as the medium through which the living and dead remain connected and in contact (Davies, 1985). Although, as in the case of the imagery on white-ground lêkythoi, it is not always easy to determine the identity and status of all depicted figures, it is thought that this gesture shows the close relationship between family members despite the separation that death causes. The dexiosis motif is nearly absent from white-ground imagery (the primary exception is a vase by the Painter of Berlin 2451 (Ceramicus 8954), see Giudice, 2015, fig. 12), but scenes where the living and dead meet on either side of a stêlê serve a similar, if slightly less intimate, function. The living and the dead rarely, if ever, make physical contact in vase imagery, but it seems that the divide between the two was softened or blurred by the time that white-ground lêkythoi fell out of popularity.

While the difficulty of distinguishing the living from the dead can be frustrating in terms of interpreting particular graveside images, it has the benefit of making the deceased soul more relatable. By extension, this may have made the afterlife seem less foreign and worrisome, and it also suggests that the gifts that are offered at the grave will be, at least conceptually, intelligible and desirable to the dead. There may be comfort in knowing that the only thing that was taken from the dead when they transitioned over to the afterlife is whatever essence made them living. Since they look the same as they did in life, it is easier to imagine that the dead had the same desires, wants and needs, and thus the bereaved could make a good estimation of what offerings they might desire.

Throughout much of the 5th century BCE, eidôla typically appeared passive and stoic. Rarely, if ever, does one get a sense that the deceased had any emotion, and they do not seem capable of visually indicating their acceptance of the gifts offered to them. In the case of male eidôla, there are many instances in which they appear statuesque. Like contemporary sculpture, they are portrayed heroically nude and posed in a manner that highlights their toned physiques. The beauty and symmetry expressed in the body of a heroic warrior was often equated to the embodiment of particular masculine Athenian virtues. We are not necessarily meant to imagine that this is how the deceased actually looks, or even how he looked at the time of his death, but this is a strategy used by the vase painters to convey honour and glory. Since the grave was meant to create a lasting memory of the dead and to highlight their glory and merit, these representations likely reflect the memory that was being cultivated at their particular grave. Thus, in these instances the eidōlon is not actively interacting in the scene, but they do provide a more personal and expressive representation of the deceased than images of corpses ever had. Although eidôla on white-ground lêkythoi are presented as relatively motionless and powerless, the relationship that they have to their mourners is different from that which corpses had. This is in part because they are shown standing rather than prostrate on a bier. Since they visually mirror the living, who have visited the grave by their own volition, it is easy to imagine that they too have made a choice to be present at the grave.

Towards the end of the 5th century BCE, there is a noticeable shift in the way that the deceased souls are portrayed. The figures associated with two particular workshops, Group R and Group G, are often described as being rather emotive with brooding and gloomy facial expressions reflective of inner feelings of dejection or sadness (cf. e.g. Kurtz, 1975, p. 222; Oakley, 2004, p. 167 and Robertson, 1992, p. 253). On a very basic level, such images suggest that like the living, the dead had the capacity to feel various emotions. This is a notice able change from the inanimate, senseless souls that appear in Homer and the expressionless souls found in the majority of Athenian funerary imagery (Johnston, 1999, pp.7–9 and Sourvinou-Inwood, 1996, pp. 77–94). The mere fact that these souls are capable of expressing emotion is of note in and of itself, but it is particularly disconcerting that there are no examples of decidedly happy souls. A demonstrative example of a ‘grumpy’ soul by Group R can be found on a vase now in the National Museum in Athens (1816) (Oakley, 2004, fig. 126). In this particular scene, two mourners approach a broad stêlê upon which a young man holding a pair of spears slumps. Each of the mourners appears to be frowning as they look at the grave. The eidōlon is shown in three-quarter view and he occupies the entirety of the grave marker by the way that he slouches upon it. The weight of his posture creates a sense of fatigue and depression. While we expect mourners to be sad as they visit a grave, the sadness of the deceased warrior is not as easy to understand. On the one hand, his sombre countenance may merely reflect that he is saddened by his fate. As he represents a soldier, his attitude may also reflect a broader feeling of hopelessness and fatigue that extended years of fighting may have inflicted upon the Athenian people. The notion that the soul might bewail its fate was not new in the 5th century BCE, and Hector’s soul was described as lamenting as it exits is corporeal host (Iliad 22.361–363). However, the difference between Hector’s soul crying out at its misfortune and an image of a sad eidōlon on a white-ground lêkythos looking depressed by its fate is that the former is a moment of sadness at the realization of death, whereas the latter would seem to be more representative of a lasting feeling of sadness that might potentially accompany an infinite afterlife.

If we consider that one of the functions of eidôla in graveside scenes is to provide a visible recipient of funerary gifts, it is unfortunate to think that despite one’s best efforts to nurture or appease the dead, they continue to feel depressed. Since these images coincide with a period during which there is an apparent increase in the number of curse tablets, or katadesmoi, found in Athenian grave contexts (Garland, 2001, pp. 6–12 and Johnston, 1999, pp. 71–86), these images may reflect growing anxiety about the feelings of the deceased. The increase in the use of curse tablets indicates a widespread belief that the dead were potentially dangerous and able to affect the living. To avoid upsetting potentially volatile souls and to keep all souls happy in general, tending to the grave may have been perceived to be increasingly important towards the end of the 5th century BCE. Such images may have served as a reminder that constant vigilance toward the needs of the dead was not just a nice activity, but had potentially important ramifications.

By the end of the 5th century BCE, funerary imagery seems to have become increasingly interested in the experience of the afterlife and how one might express this through the emotion and posture of representations of the soul. Anxiety about death and about the turmoil that it might cause seems to have inspired great changes in the ways that the Athenians perceived that the dead could impact their lives. Although the boundary between the living and the dead had long been presented as utterly impenetrable, over time this boundary seems to have transformed and become more permeable. Eventually, we find evidence that Athenians believed themselves capable of affecting and influencing the wellbeing of the dead, and the grave was accepted as the space at which this influence was best expressed. As this idea gained traction, the lives of Athenians must have been increasingly affected by thoughts of the afterlife and their continued obligation to care for the dead, knowing well that they had the ability to create a comfortable, hospitable eternity for their loved ones. The grave came to represent the space at which families could exercise control over the fate of their loved ones in the afterlife and so it replaced the prothesis as the favoured funerary image.

1 The vase imagery discussed in the text but not included in the figures are referenced using the following abbreviations: ARV2 = J.D. Beazley (1963) Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters, 2nd Edition, Oxford, Clarendon Press; CVA = Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum; LIMC = Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (1981–1999); MFA = Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; MMA = Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; NM = National Museum; Para = J. D. Beazley (1971) Paralipomena, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Ahlberg, G. (1971) Prothesis and Ekphora in Greek Geometric Art, Göteborg, P. Åström.

Arrington, N. (2014) ‘Fallen Vessels and Risen Spirits: Conveying the Presence of the Dead on White-Ground Lêkythoi’, in J. H. Oakley (ed.) Athenian Potters and Painters, vol. 3, Oxford, Oxbow Books, pp. 1–10.

Arrington, N. (2015) Ashes, Images, and Memories: The Presence of the War Dead in Fifth Century Athens, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Blok, J. H. (2006) ‘Solon’s Funerary Laws: Questions of Authenticity and Function’, in J. Blok and A. P. M. H. Lardinois (eds) Solon of Athens: New Historical and Philological Approaches (Mnemosyne Suppl. 272), Boston, Brill, pp. 197–247.

Boardman, J. (1955) ‘Painted Funerary Plaques and Some Remarks on Prothesis’, The Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. 50, pp. 51–66.

Closterman, W. E. (2014) ‘Women as Gift Givers and Gift Producers in Ancient Athenian Funerary Ritual’, in A. Avramidou and D. Demetriou (eds) Approaching the Ancient Artifact: Representation, Narrative, and Function: A Festschrift in Honor of H. Alan Shapiro, Boston, De Gruyter, pp. 161–174.

Davies, G. (1985) ‘The Significance of the Handshake Motif in Classical Funerary Art’, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 89, pp. 627–640.

Garland, R. (1982) ‘Γέρας θανόντων: An Investigation into the Claims of the Homeric Dead’, The Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies of the University of London, vol. 29, pp. 69–80.

Garland, R. (2001) The Greek Way of Death, London, Duckworth.

Giudice, E. (2015) Il Tymbos, la Stêlê, la Barca di Caronte: l’Immaginario della Morte sulle Lêkythoi Funerarie a Fondo Bianco. Rome, L’Erma di Bretschneider.

Hame, K. (1999) Ta Nomizomena: Private Greek Death-Ritual in the Historical Sources and Tragedy. Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College.

Heath, J. (2005) ‘Blood for the Dead: Homeric Ghosts Speak Up’, Hermes, vol. 133, pp. 389–400.

Houby-Nielsen, S. H. (1995) ‘ “Burial Language” in Archaic and Classical Kerameikos’, in S. Dietz (ed.) Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens: vol. 1, Aarhus, University Press, pp. 129–192.

Huber, I. (2001) Die Ikonographie der Trauer in der griechischen Kunst, Mannheim, Bibliopolis.

Johnston, S. I. (1999) Restless Dead: Encounters between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Kurtz, D. C. (1975) Athenian White Lekythoi, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Kurtz, D. C. and J. Boardman (1971) Greek Burial Customs, Ithaca, Cornell University Press.

Oakley, J. H. (2004) Picturing Death in Classical Athens: The Evidence of the White Lêkythoi, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Paton, W. R. (trans) (1953) The Greek Anthology, Volume 2: Book 7: Sepulchral Epigrams, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Put, W. van de (2011) Shape, Image and Society: Trends in the Decoration of Attic Lêkythoi, Ghent, University Press.

Robertson, M. (1992) The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Shapiro, H. A. (1991) ‘The Iconography of Mourning in Athenian Art’, The American Journal of Archaeology (AJA), vol. 95, pp. 629–656.

Sourvinou-Inwood, C. (1996) ‘Reading’ Greek Death to the End of the Classical Period, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Vlachou, V. (2012) ‘Death and Burial in the Greek World: Addendum Volume 6’, ThesCRA VII, Malibu, Getty Publications, pp. 363–384.

Wees, H. van (1998) ‘A Brief History of Tears: Gender Differentiation in Archaic Greece’, in L. Foxhall and J. Salmon (eds) When Men Were Men: Masculinity, Power and Identity in Classical Antiquity, New York, Routledge, pp. 10–53.