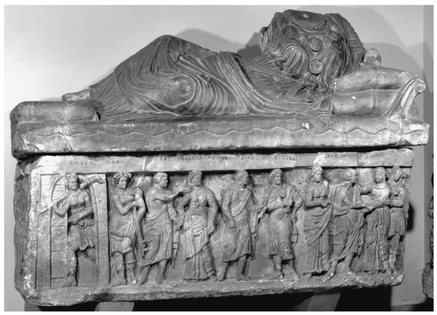

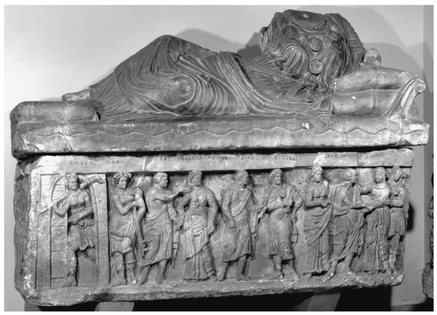

Figure 3.1 Sarcophagus of Hasti Afunei, ‘Antonino Salinas’ Museum, Palermo, inv. N. I. 8464 (Archivio Fotografico del Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonino Salinas di Palermo)

The Etruscan Netherworld and its demons

Isabella Bossolino1

Etruscan religion and its artistic displays have always captivated travellers and amateurs since the first discoveries of painted tombs in the eighteenth century (see Harari, 2012). Until the second half of the last century, Etruscan religion was a promising but only partially explored research field (Thulin, 1906 was however fundamental), but since the publication of famous Ambros J. Pfiffig Religio Etrusca (1975), scholarly contributions on this subject have increased exponentially (Maggiani and Simon, 1984; Colonna, 1985; Maggiani, 1992; Briquel, 1997; Gaultier and Briquel, 1997; Torelli, 2000; de Grummond 2006; de Grummond and Simon, 2006).

A particularly popular, and rather peculiar, sector of Etruscan piousness is demonology: everything that concerns all the numerous demon figures, monstrous or not, that inhabit the Netherworld together with the major divinities of Greek ascendant. One of the first scholars to deal with them was Pericle Ducati in 1916 (Ducati, 1916). Since then, interest in these figures has continued to rise and scholars have started to focus on the individual figures. The first to receive particular attention was predictably Charu, fully earthly and rarely marine, Etruscan interpretatio of the underworld ferryman of the Greeks (De Ruyt, 1934). In the following years, scholars concentrated mainly on the choral dimension of underworld population, with contributions (from the pioneering Krauskopf, 1987 to the recent Krauskopf, 2013; in the years in between, Jannot, 1988; Jannot, 1993; Steiner, 2004; Ostermann, 2008) that have considered all the existing figures (known or anonymous) in order to understand their roles and functions (see Sacchetti, 2011 about Felsinean stelae).

These demonic figures obviously have a special relationship with the journey of the dead, as the Etruscans might have imagined it, and with the topography of the Netherworld the dead have to explore.

The most ancient tomb paintings do not offer a precise picture of the Etruscan underworld: they usually offer images of happy banquets and convivial moments or natural scenery (Pallottino, 1984, pp. 338–339). There is no fixed conception of the Underworld and of the journey the dead have to undertake until the late classical era (end of the IV–beginning of the III century BCE), when the Dionysian and mystery religions became largely popular (Brendel, 1995, pp. 337–339; 423–425).

As proposed by Marisa Bonamici (Bonamici, 1998), it is possible to try and retrace the Underworld topography and the journey of the dead in Greece through the words of Aristophanes, who, in Frogs, offers valuable testimony, since he is forced by the theatrical representation to sketch an underworld topography that would match the eschatological conceptions that were common in his culture at the time. It is likely that there were similiraties between the conception of the underworld in Classical Athens and in Etruscan society, as Etruscan society was strongly hellenised, particularly since the Classical period (see de Grummond, 2006, p. 113, in particular about religion).

The journey that Dionysus, ‘of Gods and men surely the biggest coward’ (v. 486; all the English quotes of the play are taken from Dillon, 1995), in disguise as Heracles, undertakes to get to the Netherworld and bring his beloved Euripides back to life consists of different steps. As Bonamici outlines, there are four fundamental passages (Bonamici, 1998, p. 4). First, Dionysus needs to get to ‘an enormous lake, a fathomless abyss’ and manage to get across. There are two possible ways to cross the marsh: paying two obols to an old mariner (of course, Charon) that will bring the traveller to the other side, or running around the lake,2 since the aged mariner refuses to carry the slave Xanthias (vv. 180ff.). After the crossing, the meeting point for the two companions is at the Stone of Withering, where a new path begins: Heracles foretells ‘ten thousand snakes and terrible wild beasts’. Later the travellers will meet a ‘slough of ever-flowing dung’, where patricides and liars lie (v. 272). In this fearful land, the travellers meet the monster Empusa, a terrible creature that can take on dozens of different shapes, now cow, now mule, now beautiful woman, sometimes with a bronze leg and another leg made out of manure (vv. 277ff.).

When Empusa leaves – the two companions are too cowardly to fight her they finally get to the most beautiful parts of the Underworld. They reach a blooming meadow lit by torches, where the initiates sing a hymn to Iacchus, son of Zeus and Demeter, associated with the Eleusinian mysteries (vv. 431ff.). Dionysus and Xanthias’ journey stops here, but the topography of the Netherworld proposed by Aristophanes knows another place, too: a dark, rocky area, located in the depths of the earth, where the Acheron, Styx and Cocytus flow and the damned have their guts eaten by the Tartesian Eel, the Tithrasian Gorgons and the horrible monster Echidna. This is the place where Aeacus, the wise guardian of Persephone and Pluto’s palace, wants to send Dionysus, the moment he sees him and thinks he is Heracles, who stole Cerberus from Hades (vv. 465ff., see Bonamici 1998, 4). This description of the Greek and, as we will see, Etruscan Netherworld emphasises two main things: the value and meaning of some natural elements and the fundamental importance of otherworldly guides. These are the elements on which this chapter will focus.

As we saw through Aristophanes’ narration, the focal points of the journey to the Underworld are the rocks, both as elements of the natural setting and as spatial markers, a conventional sign in order to indicate a point of separation with spatial character. Rocks are surely perfect to typify dark and dreadful places like the ones that comprise the Underworld – this is what Aeacus says in his threat to Dionysus dressed as Heracles – but more interesting for our analysis of the otherworldly topography is the meaning of the rock as a geographical marker of the different areas of the realm of Hades. We already saw an allusion to the Stone of Withering and a description of the frightful, rocky place with eels, gorgons and other monstrous beasts in Aristophanes. In order to explore rocks in Etruscan religion and beliefs, however, it is necessary to find comparable examples in material culture and iconography (see de Grummond, 1982).

The case of the Cannicella Sanctuary in Orvieto is fundamental to understanding this topic (see Stopponi, 1996 with bibliography). The sanctuary is set on a ledge a little west of the city, densely surrounded by necropolises on the eastern and the western sides; it was discovered in 1884 and has been excavated and studied by Perugia University since 1977 (see Colonna, 1987). Going from east to west, one will first meet a big room made out of ‘opera a scacchiera’ (see Camporeale, 2013, p. 199); then the central area including the temple structure, south-east oriented, with opus africanum walls; and finally the broad western terrace, characterized by a complex water system dominated by a big basin close to which the circular altar considered to be the base of the famous Venus statue, also found in this area, was discovered (see Roncalli, 1987, pl. III; Roncalli, 1994, pp. 100–103). In this sector is a sort of rock counter, presenting a surface marked by various hollows and by a clear, rough longitudinal rut, that unravels on one side towards a logline, on the other towards the place where the cult statue probably stood. This is most probably a surface area for sacrifices, where the victims’ blood was guided in the two directions (Roncalli, 1994, p. 102).

During the 1984 excavations, on the eastern area of the ledge a small limestone altar was brought to light (Roncalli, 1994, pp. 103-104), surely in a secondary context3, reused in medieval walls but most probably coming from the western sector of the sanctuary, where the measures of the internal opening and the cavities of the smaller basin perfectly fit. The altar measures 40 x 41 cm for 32.5 cm height. The four sides bend and narrow towards the top and are surmounted by a rectangular crowning element, characterized by a dense network of short and deep furrows that must be interpreted as trails of the repeated impact of cutting tools and give it the appearance of a cutting board (Roncalli, 1994, figs. 16-27). The measurements of the altar, and of the underlying small tank, remind us of the one square cubit bothros that Circe tells Odysseus to dig in order to attract the dead shadows through libations (Homer, Odyssey, K 517; see Roncalli, 1994, pp. 103–104).

The amorphous character of the altar, though, and the repeated cuttings on its upper surface allow us to see here a precise reference to an important element we already saw in Aristophanes’ description of the Underworld: as already speculated by Francesco Roncalli, its appearance looks like a deliberate allusion to the natural rock, whereby the small altar, whose height was to coincide with the floor, would look almost like a rock emerging from the ground (Roncalli, 1994, p. 112). The chthonic significance of the rock (Roncalli, 1997, p. 49; see also Pontelli, 2017, with bibliography) is already clear in the passage quoted before, to which we can relate a fragment from the Odyssey, too, where we learn that the geography of the Netherworld puts Hades’ doors exactly in the place where a rock, visible from the distance, marks the confluence of the infernal rivers Pyriphlegethon and Cocytus into the Acheron (Homer, Odyssey, K 515).

Certain examples from material culture, added to the literary evidence collected by Francesco Roncalli (1994, pp. 113–114), confirm the strong symbolic meaning of natural rocks in Etruscan funerary and chthonic conceptions. The oldest is the well-known Tomba dei Demoni Azzurri, built and painted in Tarquinia around 430–400 BCE (Roncalli, 1997, pp. 37–43; Adinolfi et al., 2005a, 2005b). The scene on the right wall depicts a woman in the middle of the scene, escorted more or less gently by two demons: she is most probably the newly deceased, joining her predeceased relatives, just after having come through the Underworld doors indicated on the right (the tomb’s door is also located here!) by the big rock on which two other demons are seated (Roncalli, 1994, p. 113).

Relatively more recent, but equally telling, is the sarcophagus from Torre San Severo (Herbig, 1952, p. 40, pl. 36; Roncalli, 1994, 114; Weber-Lehmann, 1997, n. 12). This peperino stone sarcophagus, of the Holzkasten type, is dated to the second half of the fourth century BCE. It presents reliefs with mythological scenes on all four sides. On one of the long sides, framing a scene of Trojan prisoners being sacrificed by Achilles in honour of Patroclus, are two winged female demons: dressed in a very similar way with long chitons and flat shoes, adorned with jewels and snake-shaped tiaras, they point towards the scene and lift the snakes tightly held in their hands. Two bearded demons, standing on the border of the scene on the second long side, are their ideal counterpart: they equally turn to the action (in this case, Polyxena’s sacrifice on Achilles’ grave) holding a snake in each hand and significantly placing a foot on rocky spurs. Achilles’ posture is meaningful too, since he, in the form of dead shadow, is also leaning with his right leg on a rock emerging from the ground.

This last find relates to the final focus point of this contribution: renowned demons. Charu, the old mariner that also appears in Aristophanes’ work, has been shown already, but in this last part I will be concentrating on a less studied but extremely important figure: Vanth (see Enking, 1943; von Vacano, 1962; Fauth, 1986; von Freytag, 1986; Spinola, 1987; Weber-Lehmann, 1997).

From the very first stirring of interest in these peculiar inhabitants of the Etruscan Underworld, the general idea that scholars have proposed was one of interchangeable figures: apparently, every demon could perform any kind of function, without a clear division of responsibilities. Even today, there is no clear distinction made between the roles of the different demons and it is assumed that they can perform indiscriminately this or that task. It is my argument, though, that this statement does not hold true: not only do demons have their characteristic and distinct roles and cannot perform all the possible otherworldly duties with no distinctions between them, but it is also possible today to discern differences between demons that were once considered to be the same entity.4

Vanth, a female demon characterized by her beautiful appearance and her usually amazon-like outfit, appears iconographically for the first time in the second half of the fourth century BCE, but her name is already mentioned on an Etrusco-Corinthian aryballos of the orientalising period. She is found in almost every area of the Underworld: at the beginning of the journey with the deceased, in the middle of their difficulties helping them out, in the Elysian Fields. For this reason, it was believed until recently that Vanth could fulfil every kind of tasks, and that she was not significantly different from other Underworld demons (Jannot, 1997). Through an iconographic and epigraphical analysis, though, it is possible to define precisely which duties are the responsibility of Vanth and which not; even more importantly, it is possible to differentiate her from other demons who look like her but perform other functions.

Two particular examples will illustrate this point. One is a calyx-krater from Camporsevoli, whose current location is unfortunately unknown (Weber-Lehmann, 1997, n. 51; Bonamici, 2005; Bonamici, 2006). On one side, three figures are visible (Bonamici, 2006, fig. 1). On the left, a winged female demon, dressed in a long pleated chiton with decorated hems and a heavily adorned cape, turns her head and walks in the opposite direction of the other two figures; however, she raises her arm towards them and shows her palm. The other two characters, a bearded bare-chested man holding a gnarled wooden stick and a young man characterised as Hermes (carrying a caduceus and wearing a petasus),5 greet each other. On the other side, the same female figure approaches and takes the wrist of a bearded man, similar to the previous one (scholars assume that a stick is to be integrated in his left hand, since the section is worn, Bonamici, 2006, note 3), shown speaking with another figure.

Bonamici sees here a role exchange and a hand-over between the two iconic psychopomps, Turms and Vanth (Bonamici, 2006, p. 526). The female demon’s gesture, at first glance so unusual, can identify a break in the journey on which the demon and the dead have embarked, with an alternation of the two psychopompic entities, each one ready for and in charge of a certain part of the journey. In this case, Vanth is responsible for the first section, Turms for the path into the Netherworld.

This interpretation can be compared with that of a scene on a Villa Giulia stamnos (a Faliscan6 stamnos attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter 1660: Rome, Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, inv. 1660; see Krauskopf, 1987, pp. 50-51; Weber-Lehmann 1997, n. 9), where Turms and a female demon recognisable as Vanth are once again shown together. The gestures are dramatically rendered here too, but the female demon’s attitude is again not hostile. The stamnos displays a journey to Hades: on the left, a female winged demon, dressed in a long chiton, with a snake in each hand, looks at two figures behind her, while walking to the left; Hermes with his petasus and caduceus is following, while putting his arm around the shoulders of a woman equipped with a thyrsus (usually associated with Dionysus, it is a staff of giant fennel covered with ivy vines and leaves, sometimes wound with taeniae and always topped with a pine cone).

Describing the scene, Beazley talks of Hermes who ‘defends the dead woman from a demoness: he wards off the attacker with the butt of his caduceus, and she turns and flees, looking round reproachfully’ (Beazley, 1963, p. 152). Looking at the pictures on the vessel, to call the quite unbiased demon’s look reproachful seems like an exaggeration – on the contrary, it looks like the demon is just turning towards her companions, as if to be sure of their presence. Moreover, comparing this stamnos with the Camporsevoli krater, we can see two interesting details: first of all, we find the pairing of Vanth and Turms once again as the psychopompic couple par excellence (together with the Vanth–Charu pairing). Consequently, the gesture of the stick pointed towards another figure does not have to be negative, since it can be found depicting a friendly greeting between the deceased and the young deity.

Thus, I propose an interpretation of this stamnos linking it to the krater from Camporsevoli: in my opinion, it is possible to identify here a kind of hand-over between two psychopompic demons, each of them entrusted with a particular part of the otherworldly journey. The female demon, recognisable as Vanth, brought the woman up to the point where her expertise was adequate, but now goes away, leaving the deceased in Turms’ (Turms Aitas here, the psychopompic demon who works for Hades; see LIMC, s.v. Turms) expert hands, who will take care of her, probably until her final destination.7

Even more understudied is the figure of Vanth taken independently from a crowd of blurred female demons, often similarly dressed and winged, that populate the otherworldly depictions so typical of the Etruscan art of the Classical and Hellenistic period. A quintessential case study is represented by the sarcophagus of Hasti Afunei (Weber-Lehmann, 1997, n. 6 with bibliography. See also Paschinger, 1992, p. 15; Barbagli and Iozzo, 2007, p. 91; de Angelis, 2015), dated to the end of the third century BCE and preserved in the Antonio Salinas Museum of Palermo (inv. N. I. 8464). On the main side (Figure 3.1), the moment of the parting of the deceased (Hasti Afunei) from her husband and family and from other notables is represented. On the right, a winged female demon with an uncertain tagline – some scholars read Leinth (Paschinger, 1992, p. 17, b), some simply Vanth (Herbig, 1952, pp. 41–41, n. 76 among others) – takes the woman by her shoulder and exhorts her to leave her dear ones and start the journey to the Netherworld. On the left, another female demon (whose tagline reads Culsu), wearing a huntress outfit and holding a torch on her right shoulder, comes out with a determined pace from a door that is probably the door to Hades; on her right, another female demon, identically dressed, with small wings on her forehead and endromides (leather boots, sometimes without laces, calf or knee high), watches the parting scene leaning on a big object, perhaps a key.

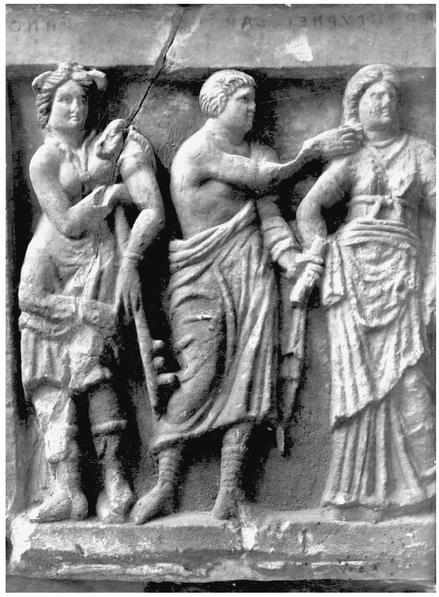

The first figure to capture our attention is surely the one labelled as Vanth (Figure 3.2). The female demon, in a hunting outfit, does not actively participate in the scene but, standing on the boundary of the entrance to the Netherworld, seems to be waiting for the parting moment to be finished. Her wings – this time protruding not from her back, as they are normally, but from her forehead, recalling the Medusa Rondanini iconographic type – become here especially meaningful: the comparison with the Gorgon image makes it possible to understand their chthonic significance, almost as a death signal.

Keys are not a common feature for Etruscan winged demons,8 but are quite meaningful (see Capuis and Chieco Bianchi, 2013, p. 62, for example, for their meaning outside Etruria). There is surely a connection between the door on the

Figure 3.1 Sarcophagus of Hasti Afunei, ‘Antonino Salinas’ Museum, Palermo, inv. N. I. 8464 (Archivio Fotografico del Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonino Salinas di Palermo)

Figure 3.2 Detail of the figure of Vanth (Archivio Fotografico del Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonino Salinas di Palermo)

left and the door to Hades, whose guardian could be Vanth, as in the Anina Tomb (Moretti, 1974, p. 136; Spinola, 1987, p. 65; Weber-Lehmann, 1997, n. 4). The key being an unusual object, it is quite difficult to identify it with certainty; some comparisons are to be found in Charu’s representations, whose most frequent feature, after the hammer, is the key. In the Querciola Tomb II, the Charu on the right seems to hold a sort of hook, which is in actuality a key with two prongs (‘une sorte de crochet, qui est en réalité une clé a deux saillants’, Jannot, 1993, p. 71); the demon in the Tartaglia Tomb, instead, holds a three-pronged key. These keys are a model used exclusively for monumental doors/gates (‘Ces clés sont d’un modèle utilisé exclusivement pour les portes monumentales’), which seems likely also for the key held by our Vanth, suitable for the closing of bars (Jannot, 1993, p. 71).

There is another variation on this type of female demon. This second figure of Vanth can be identified on a small clay urn from San Mariano (Brunn and Körte, 1890, III, p. 94, 5; Scheffer, 1991, p. 57), in the area of Perugia. In the middle of the principal decoration, a cloaked man, holding a scroll in his left hand, stands between two demons, looking at a female demon on the left,9 who puts her right hand on his shoulder; the demon is winged, dressed in a short rolled chiton that leaves her breast uncovered and with hunting boots. She places a foot on a rocky elevation and holds an object that can be identified as a two-pronged key in her right hand (see Jannot, 1993, especially the Tartaglia Tomb’s Charu). On the other side stands Charu, wearing a short cloth on the hips, boots, and with his head covered by an animal skin. He calmly observes the other two figures, holding a lowered hammer in his right hand.

Going back to the sarcophagus of Hasti Afunei – and leaving for the moment the figure of Culsu, the demon on the left coming out of the door to Hades – it is interesting to note how the demon on the right end of the scene is usually variously interpreted, since only the last three letters nth are readable. Elfriede Paschinger proposes a demon named Leinth, who, with Vanth and Culsu, would form an otherworldly triad comparable to the Greek one headed by Hecate;10 Leinth would be responsible for mancipatio, i.e. she would take the deceased and bring them away from their families towards the Netherworld (Paschinger, 1992, p. 15).

The reading of the ‘nth’ as the name Leinth, however, looks unlikely to me, not only because of the objective reading difficulties connected to the poor state of preservation of the right side of the sarcophagus, but also for iconographic reasons. The name Leinth can be found inscribed within Etruscan art as a whole only three times: on a mirror preserved in Perugia (fourth century BCE; Gerhard, 1845, pl. 141), on a mirror in Hamburg (end of the fourth century BCE; Liepmann, 1988, p. 18), and on one in the Antikensammlung in Berlin (end of the fourth century BCE; Gerhard, 1845, p. 166). On the first mirror, the figure labelled as Leinth looks very different from the one on the sarcophagus: she is dressed in a long peplum, adorned with a necklace and a ribbon in her hair, and she accompanies another female figure named Mean (a female divinity personifying victory, LIMC VI, I, p. 383) who crowns a young Heracles. Thus, her role seems to resemble much more that of the Lasae (winged female demons who can appear in association with different gods, especially Aphrodite, performing several tasks) than that of a chthonic divinity.

On the second and third mirrors, the name Leinth is found in association with male figures. On the Hamburg mirror, which is unfortunately very damaged, on an architectural background stands a group of six figures, of which only four are preserved: in the middle, a naked male figure holds a naked child in his arms and gives the other three figures on the right, Minerva, Turan and a naked young female figure, labelled as Leinth, a look. On the Berlin mirror, even though the scene looks quite difficult to decipher, we see a group of four figures: Minerva, in the middle, supports a naked baby with bullae around his neck on a volute krater (the tagline identifies him as Maris Husrnana); in front of her, Turan watches the action; on both sides, two young male figures lean on spears and look towards the principal scene: one wears a chlamys around his neck, the other, Leinth, holds another naked baby with bulla, named Maris Halna, on his leg.

As Camporeale correctly notes in the related LIMC entry (VI, I, p. 249–250), the Leinth figure does not seem to have a set iconography and it is thus very difficult to ascribe to it a specific meaning. Even though the name seems to recall the funerary sphere (LIMC VI, I, p. 249), its actions do not correspond at all with it. It is thus difficult to reconcile this with the figure appearing on the sarcophagus, not only in the shape of a winged demon, but even more as an entity strongly connected with death.

If, instead, the figure on the sarcophagus where only the final letters of the label -nth are visible was to be read as the name Vanth appearing for a second time – the possibility that I prefer – this would be the only example of the doubling of the demon confirmed by the inscriptions. Therefore, the range of Vanth’s roles would be expressed visually with the repetition of two similar demonic figures: the souls’ escort from the parting moment from the family and the benevolent figure that welcomes them at the threshold of the Netherworld, never going further but always making sure of the success of the dead’s last journey.

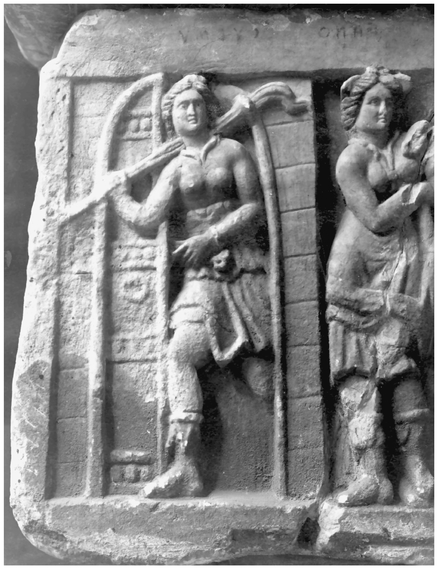

The figure of Culsu appears just once with an inscription, on Hasti Afunei’s sarcophagus, at the left of the scene (Figure 3.3) she is shown in the act of coming out of a half-open door with a lit torch on her shoulder and an object difficult to identify in her left hand. Paschinger (1992) and other scholars see some scissors, making Culsu an Etruscan equivalent of the Moirai; however, as Ingrid Krauskopf convincingly proved (Krauskopf, 1986, p. 158), not only were two handled scissors not attested in the pre-Roman period, but the Moirai were traditionally portrayed with the features of globe, spindle and sundial, never with scissors – in literature, too, the subject of the cutting of the destiny’s thread makes it first appearance quite late, not before the imperial period (RE XV, 2: 2479). Iconographically, Culsu looks just like Vanth: she wears a short chiton rolled to the waist, crossed braces on her chest and high hunting boots; unlike the other two demons in this relief, however, she has no wings.

Figure 3.3 Detail of the figure of Culsu (Archivio Fotografico del Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonino Salinas di Palermo)

It is impossible to find other epigraphical examples of the demon’s name, but a reference to her name is probably to be seen on the liver of Piacenza (van der Meer, 1987).11 In the region numbered as 14 (by the reading of van der Meer 1987 and Morandi 1988) is the inscription cul alp, two names that do not appear anywhere else on the liver; given the presence of a break between the two words, the theory that culalp could be a mistake for *Culans, an hypothetic variant of the theonym Culsans (see Krauskopf, 1986; Maggiani, 1988), has recently been ruled out (van der Meer, 1987, p. 75; Krauskopf, 1986 identifies cul as a separate element). That cul refers to Culsu or Culsans cannot be said with certainty, but the Culsu hypothesis is probably preferable, since the word is found in the regiones dirae, where we usually locate the names of divinities connected to the chthonic sphere (van der Meer, 1987, p. 80).

The first scholar to notice the connection between the culs* root and the liminal ambit was Ingrid Krauskopf (1986), who translates it as ‘Hafen, Tor’ and relates it with the concepts of seeing and protecting, just like the Umbrian deity Spetur (theonym coming from the Eugubine tablets, see Enking, 1943, p. 56; Pfiffig, 1975, p. 246). Controlling and protecting the door seem to be the duties of both Culsu and Culsans, one in terms of the Netherworld (being a connection, too, between the regiones dirae and the regiones maxime dirae on the liver of Piacenza), the other for the world of the living. This interpretation has been supported by Helmut Rix (1986). The -u suffix would identify a person that is intrinsically connected with the object indicated by the noun root – thus, culsu would indicate the essential terms connected with doors and gates (Rix, 1986, p. 313).

Once that Culsu’s relevance to the control of the door (obviously, the door to Hades) has been established, it is necessary to explain the relationship between this demon and Vanth, whom she appears next to on the Hasti Afunei’s sarcophagus. Jannot (1997, p. 146) sees in the word culsu an attributive for Vanth herself, that could be interpreted as ‘the door Vanth, the one in front of the door’. As Marisa Bonamici has highlighted, however, culsu cannot be an adjective of specification, but a noun or a first name only, as is clearly showed by Rix’s etymology (Rix, 1986, p. 313).

I would like to draw attention to an iconographic element that has been overlooked until now. If one observes the sarcophagus preserved in Palermo, it is possible to notice an important detail: Culsu is the only one of the three demons not to have wings, while the two Vanth are provided with them, one on her back, the other on her forehead. The wings, although lacking in other Vanth representations, cannot be left out in this case, since they clearly differentiate between the female demons. The door guardian’s role, performed by Culsu, does not require the same degree of mobility that is, on the contrary, typical of Vanth, who fetches and escorts the dead during their journey to the Netherworld; Culsu does not have to be speedy and this fact is pointed out precisely by the lack of wings.

I do not consider these elements accidental, and thus believe that it is impossible to identify a Vanth-Culsu, a static guardian of the door, alongside Vanth, the quick mentor of the dead and benevolent expression of otherworldly hospitality. In the apparently chaotic universe of Etruscan demons it is thus possible to introduce some functional distinctions, that may help to clarify the different otherworldly characters’ roles: it is therefore appropriate, despite the iconographic similitudes, to recognise the individual identity of the guardian figure distinct from that of the psychopomp, which is just as distinct, though more multifaceted.

The aim of this chapter was to shed some light on the fascinating but sometimes neglected area of the Etruscan Netherworld. The conceptions that writers in the Greek Classical world had about the geography and the structure of Hades were probably also held to some extent in Etruria, particularly after the spread of Dionysian and mystery religions. Through the analysis of the Cannicella sanctuary and of the archaeological record, it is possible to highlight the importance of the natural element in the infernal setting proposed by the Etruscan religion and the strong symbolic meaning of rock, mentioned in the ancient sources but even more evident in artistic funerary productions.

Finally, and most importantly, I have identified the individual qualities and tasks of some of the most famous Etruscan demons, trying to clarify the differences between them. In order to gain a better understanding of the crowded and apparently chaotic Etruscan Hades, I find it fundamental to begin with a serious investigation and comprehension of the several actors and separate roles identifiable – having begun, in this paper, with the figure of Vanth.

1 I would like to use this space to thank Dr J. Harrisson, for the organization of the Birmingham conference and for giving me the opportunity to participate, as well as for the invaluable revision of this text. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewer of this short work for her/his precious advice and guidance. My biggest thanks also goes to the Regional Archaeological Museum ‘Antonino Salinas’, in particular to Dr F. Spatafora and Dr G. Scardina, who provided and allowed me to publish the beautiful images of the sarcophagus of Hasti Afunei attached to this chapter. Finally, I owe a debt of greater gratitude to Prof M. Harari, who is responsible for the idea behind this work and many of the most interesting insights.

2 This double path is particularly clear if one looks to the Tomba dei Demoni Azzurri in Tarquinia. The two side walls are devoted to the spouses’ journey to the Netherworld; as in the old Ceretan graves, the man’s journey is on the left wall, the woman’s on the right. The man advances on a chariot, preceded by musicians and dancers, while the woman, accompanied by ugly demons, is heading towards another woman and a child, standing close to a boat, which is most probably Charon’s ship (about the tomb, see Naso, 2005, pp. 48–50).

3 A secondary context indicates an archaeological context that has been disturbed by subsequent human activity or natural phenomena, altering the original location of an archaeological find and its stratigraphic relationships.

4 A first, fundamental distinction is the one made by Antonia Rallo in the manifold iconography of the Lasae, usually considered to define all the winged female demons related to the Etruscan world (Rallo, 1974). The most important turning point, however, is to be found more recently in Marisa Bonamici’s considerations (see Bonamici, 2006), where finally Vanth is not a factotum demon anymore, outside and inside the Netherworld, but a kind of functionary with precise qualifications.

5 The caduceus is a short staff entwined by two serpents, sometimes surmounted by wings, usually carried by Hermes and heralds in general. The petasus is a broad hat, usually made of felt, leather or straw; it was worn primarly by travellers and, in its winged version, became typical of Hermes.

6 Faliscans, although different from the Etruscans, used to appear, like the Capenates, among the confederate peoples who annually gathered at the shrine of the Fanum Voltumnae at Orvieto and are thus usually studied by modern scholars also in their relationship with the Etruscan cities (see De Lucia Brolli and Tabolli, 2013; about the shared imagery and religious Pantheon, see Harari 2010).

7 If we have a look at other forms of artistic expression, other than pottery, an interesting example to be mentioned is undoubtedly the stele 76 from Bologna, where a change of hands between demons is speculated by Elisabetta Govi (2010, p. 42).

8 Scheffer’s work, too, vaguely declares: ‘Some, but very few, demons carry keys or similar implements’ (Scheffer, 1991, p. 57). Among the artefacts published by Brunn and Körte, seemingly only two other artworks show objects interpreted as keys: an urn in Munich’s Glypthothek, where a scene from Telephus myth is associated with a Fury holding an object thought to be a key, but that could possibly be a stick (Brunn and Körte, 1870, I, p. 34, pl. XXIX, 7); and another urn coming from San Mariano (Perugia), about which see below. Another Chiusine urn, which was thought to be lost but eventually appeared in Philadelphia (Maggiani, 2015, fig. 7), shows two winged female demons, holding keys in their hands (I thank the anonymous reviewer for this useful addition).

9 The identification of this demon with Vanth is here possible because of the key, that characterises her as door guardian, and of her behaviour towards the deceased. The gesture of taking the dead by their shoulder is typical of psychopompic demons and of the otherworldly journey’s initial moment: an accurate comparison can be found on stele 84 from Bologna (Sacchetti, 2011, p. 276).

10 Hecate was traditionally connected to shadows and the Netherworld; sometimes, as ‘Ενοδία and Τριοδῖτις, also to the protection of doors and crossroads. The triad consisted of Hecate, Artemis and Selene, who she was easily mistaken for. Her three fold character – terrestrial, lunar and chthonic – was often reflected in her iconography, since she was often represented with three heads or bodies.

11 The Liver of Piacenza is an Etruscan artifact found in a field on September 26, 1877, in the province of Piacenza, Italy. It is a life-sized bronze model of a sheep’s liver covered in Etruscan inscriptions (TLE 719), measuring 126 mm by 76 mm by 60 mm and dated to the late 2nd century BCE. The liver is subdivided into sections for the purposes of performing haruspicy and the sections are inscribed with names of Etruscan deities, often abbreviated.

Adinolfi, G., Carmagnola, R., and Cataldi Dini, M. (2005a) ‘La tomba dei Demoni Azzurri: lo scavo di una tomba violata’, in Dinamiche di sviluppo delle città dell’Etruria Meridionale – Veio, Caere, Tarquinia, Vulci, Atti del 23° Convegno di Studi Etruschi, Pisa, 1–6 October 2001, Roma, Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali, pp. 431–447.

Adinolfi, G., Carmagnola, R., and Cataldi Dini, M. (2005b) ‘La tomba dei Demoni Azzurri: le pitture’, in Gilotta, F. (ed), Pittura parietale, pittura vascolare – Ricerche in corso tra Etruria e Campania. Pittura Etrusca (Santa Maria Capua Vetere 2003), Napoli, Arte Tipografica, pp. 45–59.

Aristophanes, (1995) Frogs (trans. M. Dillon) Perseus Digital Library. Available at www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0032.

Barbagli, D. and Iozzo, M. (2007) Chiusi Siena Palermo. Etruschi. La collezione Bonci Casuccini (Siena – Chiusi 2007), Siena, Protagon Editori Toscani.

Beazley, J. D. (1963) Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters, 2 ed., Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Bonamici, M. (1998) ‘Lo stamnos di Vienna 448: una proposta di lettura’, Prospettiva 89–90, pp. 2–16.

Bonamici, M. (2005) ‘Scene di viaggio all’aldilà nella ceramografia chiusina’, in Gilotta, F. (ed), Pittura parietale, pittura vascolare – Ricerche in corso tra Etruria e Campania. Pittura Etrusca (Santa Maria Capua Vetere 2003), Napoli, Arte Tipografica, pp. 33–44.

Bonamici, M. (2006) ‘Dalla vita alla morte tra Vanth e Turms Aitas’, in B. Adembri (ed) Aimnēstos: miscellanea di studi per Mauro Cristofani, Firenze, Centro Di, pp. 522–538.

Brendel, O. (1995) Etruscan Art, 2 ed., New Haven and London, Yale University Press.

Briquel, D. (1997) Chrétiens et haruspices: la religion étrusque, dernier rempart du paganisme romain, Paris, Ulm.

Brunn, H. and Körte, G. (1890) I rilievi delle urne etrusche, vol. 2, part 1, “L’Erma di Bretschneider”, Roma.

Camporeale, S. (2013) ‘Opus africanum e tecniche a telaio litico in Etruria e Campania (VII a.C.-VI d.C.)’, Archeologia dell’Architettura XVIII, pp. 192–209.

Capuis, L. and Chieco Bianchi, A. M. (2013), ‘Principi e aristocrazie’, in M. Gamba, G. Gambacurta, A. R. Serafini, V. Tiné and F. Veronese (eds), Venetkens. Viaggio nella terra dei Veneti antichi, Venezia, Marsilio.

Colonna, G. (1987) ‘I culti del santuario della Cannicella’, in Santuario e Culto nella necropoli di Cannicella. Relazioni e interventi nel convegno del 1984, Annali della fondazione per il Museo «Claudio Faina», vol. III, Orvieto, Fondazione per il Museo Claudio Faina, pp. 11–26.

de Angelis, F. (2015) ‘Il destino di Hasti Afunei. Donne e famiglia nell’epigrafia sepolcrale di Chiusi’, in M.-L. Haack (ed.), L’écriture et l’espace de la mort. Épigraphie et nécropoles à l’époque préromaine, Roma, Publications de l’École française de Rome, pp. 419–458

de Grummond, N. T. (1982) ‘Some unusual landscape conventions in Etruscan art’, Antike Kunst, vol. 25, pp. 3–14

de Grummond, N. T. (2006) Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

de Grummond, N. T. and Simon, E. (2006) The Religion of the Etruscans, Austin, University of Texas Press.

De Lucia Brolli, M. A. and Tabolli, J. (2013) ‘The Faliscans and the Etruscans’, in J. MacIntosh Turfa (ed.), The Etruscan World, London and New York, Routledge.

de Ruyt, F. (1934) Charun, Bruxelles, Lamertin.

Ducati, P. (1916) ‘Aspetti dell’arte in Etruria’, Atene e Roma, XIX, pp. 169–187.

Enking, R. (1943) ‘Culsu and Vanth’, RM 58, pp. 48–69.

Fauth, W. (1986) ‘Lasa-Turan-Vanth. Zur Wesenheit weiblicher etruskischer Flügeldämonen’, in R. Althein and M. Rosenbach (eds) Beiträge zur altitalischen Geistesgeschichte. Festschrift für Gerhard Radke zum 18. Febraur 1984, Münster, Aschendorff, pp. 116–131.

Gaultier, F. and Briquel, D. (1997) Les plus religieux des hommes. État de la recherche sur la religion étrusque, Actes du colloque international. Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 17–18–19 novembre 1992, Paris, La Documentation Française.

Gerhard, E. (1845) Etruskische Spiegel, 4 vol., Berlin, de Gruyter.

Govi, E. (2010) ‘Le stele di Bologna di V secolo: modelli iconografici tra Grecia ed Etruria’, in M. Dalla Riva and H. Di Giuseppe (eds) Meetings Between Cultures in the Ancient Mediterranean, Bollettino di Archeologia Online (edizione speciale), pp. 36–47.

Harari, M. (2010) ‘The Imagery of the Etrusco-Faliscan Pantheon between Architectural Sculpture and Vase-painting’, in L. Bouke van der Meer (ed.) Material Aspects of Etruscan Religion. Proceedings of the International Colloquium. Leiden, May 29 and 30, 2008, Babesch Supllements 16, pp. 83–103.

Harari, M. (2012) ‘Le tombe ‘inventate’ di padre Forlivesi’, in M. Harari and S. Paltineri (eds) Segno e colore. Dialoghi sulla pittura tardoclassica ed ellenistica (Pavia 2012), Roma, L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 107–114.

Herbig, R. (1952) Die jüngeretruskischen Steinsarkophage, Berlin, Gebr. Mann.

Jannot, J. R. (1988) Devins, dieux et démons. Regards sur la religion de l’Etrurie antique, Paris, Picard.

Jannot, J. R. (1993) ‘Charun, Tuchulcha et les autres’, RM 100, pp. 59–81.

Jannot, J. R. (1997) ‘Charu(n) et Vanth, divinités plurielles’, in F. Gaultier and D. Briquel (eds) Les plus religieux des hommes. État de la recherche sur la religion étrusque, Actes du colloque international. Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 17–18–19 novembre 1992, Paris, La Documentation Française, pp. 139–166.

Krauskopf, I. (1986) ‘Culsans und Culsu’, in R Althein and M. Rosenbach (eds) Beiträge zur altitalischen Geistesgeschichte. Festschrift für Gerhard Radke zum 18. Febraur 1984, Münster, Aschendorff, pp. 156–163.

Krauskopf, I. (1987) Todesdämonen und Totengötter im Vorhellenistischen Etrurien, Firenze, Leo S. Olschki.

Krauskopf, I. (2013) ‘Gods and Demons in the Etruscan Pantheon’, in J. M. Turfa (ed.) The Etruscan World, London and New York, Routledge, pp. 513–538

Liepmann, U. (1988) CSE Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2, Munich.

Maggiani, A. (1992) ‘L’uomo e il sacro nei rituali e nella religione etrusca’, in J. Ries (ed.) Le civiltà del Mediterraneo e il sacro. Trattato di antropologia del sacro, 3, Milano, Jaca Book, pp. 191–212.

Maggiani, A. (2015) ‘Magistrati e sacerdoti? Su alcuni monumenti funerari da Chiusi’, in M.-L. Haack (ed.) L’écriture et l’espace de la mort. Épigraphie et nécropoles à l’époque préromaine, Roma, Publications de l’École française de Rome, pp. 339–366

Maggiani, A. and Simon, E. (1984) ‘Il pensiero scientifico e religioso’, in M. Cristofani (ed.) Gli Etruschi. Una nuova immagine, Firenze, Giunti Editore, pp. 136–167.

Morandi, A. (1988) ‘Nuove osservazioni sul fegato bronzeo di Piacenza’, Mélanges de l’école française de Rome, vol. 100–1, pp. 283–297.

Moretti, M. (1974) Etruskische Malerei in Tarquinia, Köln, Dumont.

Naso, A. (2005) La pittura etrusca: guida breve, Roma, «L’Erma» di Bretschneider.

Ostermann, G. (2008) Etruskische Todesdämonen. Beobachtungen zu den griechischen Ursprüngen und der ikonographischen Entwicklung am Beispiel von Charun und Vanth, Saarbrücken, Verlag Dr. Müller.

Pallottino, M. (1984) Etruscologia, 7th ed., Milano, Hoepli.

Paschinger, E. (1992) Die etruskische Todesgöttin “Vanth”, 2 vol., Wien, VWGÖ.

Pfiffig, A. J. (1975) Religio Etrusca, Graz, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt.

Pontelli, E. (2017) ‘Roccia e sacro in Etruria: dal rito al segno’, in A. Pontrandolfo and M. Scafuro (eds) Dialoghi sull’Archeologia della Magna Grecia e del Mediterraneo, Atti del I Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Paestum, 7–9 settembre 2016, Paestum 2017, Pandemos, pp. 1277–1282.

Rallo, A. (1974) Lasa. Iconografia e esegesi, Firenze, Sansoni.

Rix, H. (1986) ‘Etruskisch culs* «Tor» und der Abschnitt VIII 1–2 des Zagreber Liber linteus’, Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu, 3. Serija, vol. XIX, pp. 17–40.

Roncalli, F. (1987) ‘Le strutture del santuario e le tecniche edilizie,’ in Santuario e Culto nella necropoli di Cannicella. Relazioni e interventi nel convegno del 1984, Annali della fondazione per il Museo «Claudio Faina», Vol. III, Orvieto, Fondazione per il Museo Claudio Faina, pp. 47–60.

Roncalli, F. (1994) ‘Cultura religiosa, strumenti e pratiche cultuali nel santuario di Cannicella a Orvieto’, in M. Martelli (ed) Tyrrhenoi Philotechnoi (Viterbo 1990), Roma, Gruppo Editoriale Int., pp. 99–118.

Roncalli, F. (1997) ‘Iconographie funéraire et topographie de l’au-delà en Étrurie’, in F. Gaultier and D. Briquel (eds) Les plus religieux des hommes. État de la recherche sur la religion étrusque, Actes du colloque international. Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 17–18–19 novembre 1992, Paris, La Documentation Française, pp. 37–54.

Sacchetti, F. (2011) ‘Charu(n) et «les autres»: les cas des stèles étrusques de Bologne’, RA 2011, 2, pp. 263–308.

Scheffer, C. (1991) ‘Harbingers of Death? The Female Demon in Late Etruscan Funerary Art’, Munuscula Romana (Lund 1988), Göteborg, Paul Åström, pp. 51–63.

Spinola, G. (1987) ‘Vanth, osservazioni iconografiche’, RdA XI, pp. 56–67.

Steiner, D. (2004) Jenseitsreise und Unterwelt bei den Etruskern: Untersuchung zur Ikonographie und Bedeutung, Munich, Herbert Utz Verlag.

Stopponi, S. (1996) ‘Orvieto’, in EAA, Suppl. 1971–1994, Roma, Treccani, pp. 134–140.

Thulin, C. O. (1906) Die Götter des Martianus Capella und der Bronzeleber von Piacenza, Gieszen, De Gruyter.

Torelli, M. (2000) ‘La religione etrusca’, in M. Torelli (ed.) Gli Etruschi, Cinisello Balsamo, Bompiani, pp. 272–289.

van der Meer, L. B. (1987) The Bronze Liver of Piacenza. Analysis of a Politheistic Structure, Amsterdam, Brill.

von Freytag, B. (1986) Das Giebelrelief von Telamon, Mainz, Verlag Phillip von Zabern.

von Vacano, O. W. (1962) ‘Vanth-Aphrodite. Ein Beitrag zur Klärung etruskischer Jenseitsvorstellungen’, in M. Renard (ed.) Hommages à Albert Grenier, III, Paris, pp. 1531–1553.

Weber-Lehmann, C. (1997) ‘Vanth’, in LIMC VIII, Zürich, München and Düssekdorf, Artemis Verlag.