Chapter Seven

Selective Affinities

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mustafa Dzhemilev finally had occasion to meet Boris Chichibabin and Liliia Karas-Chichibabina in person. Their encounter defied his expectations. The tall, slender Chichibabin had shyly approached Dzhemilev. “I am Chichibabin,” he said, quietly. Dzhemilev was incredulous; Chichibabin’s soft-spoken manner threw him. “It was amazing,” he remembers, “because there were few Crimean Tatars who did not know of him.” Dzhemilev shook his hand. “To us you are a legend,” he told Chichibabin.1

To understand how a modest poet from eastern Ukraine became a legend to a dispossessed Sunni Muslim nation, we embarked in part 2 on a journey with two destinations. At the first destination we find compelling evidence of a faith in literature to change the world. We are conditioned to recoil at such cliché, but to speak otherwise is to misrepresent the clarity of purpose with which artists like Boris Chichibabin, Ivan Sokulsky, or Cengiz Dağcı approached their responses to Stalin’s Crimean atrocity. It is also to misrepresent the clarity of purpose with which their readers endeavoured to compile, transcribe, and share these texts – often at risk of arrest and imprisonment. All of them sensed that imaginative literature could be not only artistically satisfying but also morally educative and politically effective in remedying what they saw as a grave injustice. In the Soviet Union a testament to this efficacy was the pre-emptive role of the literary aesthetic in confronting the deportation and its aftermath. Before journalistic reports, open letters, and other documentary texts began to inform Soviet samizdat readers about the fate of the Crimean Tatars, literary texts had already made a mark. Poetry in particular led the way.

This faith in literature was not misplaced. Stalin had condemned the Crimean Tatars to distant exile; literature helped keep them close. The reception of these texts among Crimean Tatar activists alone – who led the largest, most organized, and most sustained dissident movement in the Soviet Union – is demonstrable proof of literature’s moral traction in the empirical world. Slipped into envelopes, concealed in notebooks, these texts travelled thousands of miles to a persecuted community who drew regular consolation and inspiration from them. They were read through tears alongside national hymns. In the end, these works of literature contributed to a movement that led to state reparations for a state crime.

In arriving at this first destination, we bump up against a number of the debates that have been occasioned by ethical criticism over recent decades, arguments over whether or to what extent literature can be said to make readers “better people.” These debates can betray an Anglo-American centrism and a lack of historico-cultural contextualization that this book seeks to avoid. And at times these debates risk missing the point entirely. The issue is less that literary texts have some kind of ethical upper hand or an inside track to moral enrichment. It is that, when seeking to invite prosocial action, they do so by telling it slant. What fascinates us is their insistent rebellion. They run in a different direction from documentary, constative, propositional discourse. They choose circuitous, complicated routes to communciation, but in doing so, they can expedite understanding. As we have seen, no matter their point of origin – Kharkiv, Moscow, Dnipropetrovsk, Kyiv, Ankara, Istanbul – the texts in this study employ generic strategies and conventions (e.g., lyric address), figures of speech (metaphor), rhetorical devices (accismus), and figurative modes (allegory) that feed off textual gaps and discontinuities instead of papering over them. And for the most part, rather than engaging in banal or moralizing uplift, they seek to stimulate, model, and process feelings of guilt.

The second destination, meanwhile, offers a view of the abiding importance of the Crimean Tatars to the entire Black Sea region. For a small, displaced nation whose very mention could bring controversy, the investment of Russian, Ukrainian, and Turkish writers in their representation was steady during the height of the Cold War, in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. This significance stems from their standing not only as an indigenous people of Crimea but also as a people through whom Ukrainians and Turks especially have engaged in collective self-reflection. For Ukrainian readers, Crimean Tatars were counterparts in processes of metaphorization that cultivated national identity, while for Turkish readers, the representation of the plight of the Crimean Tatars in the Second World War, for instance, served as a font of prosthetic memory of a formative event of twentieth-century world history. The Crimean Tatars have been, in other words, a constitutive presence in the Black Sea, a consequential region maker.

As we have seen, the literary texts in part 2 moved among diverse audiences in Moscow, Kharkiv, Kyiv, Istanbul, and Ankara, capturing the attention of readers and activists and helping contribute to the sea-change in Soviet policy that led to the repatriation of the Crimean Tatars after 1989. These itineraries through sites of political and cultural power were practical and strategic, but they mapped an orbit around Crimea. They did not permeate it. Archival searches and records of literary readings in cities like Simferopol, for instance, offer only faint traces of the presence of texts like Chichibabin’s “Krymskie progulki” or Nekipelov’s “Gurzuf.” The poetry and prose at the centre of this study thus succeeded in advancing the cause of the Crimean Tatar return to Crimea, but appeared to have had less of a role before 1989 in prompting guilt-processing among readers in Crimea.

The event of the collapse of the Soviet Union, moreover, sent deep shock waves throughout the Black Sea region, reconfiguring bonds of attachment and structures of feeling. Crimea once again became a nodal point in a dense, unsettled web of shifting interrelationships. With the loss of the frame of Soviet identity, the civic we-denomination behind, say, Nekipelov’s advocacy of the Crimean Tatars as “one of us” was suddenly less salient in places like Moscow. After 1991, Russian literature accordingly registers little concern for the fate of the Crimean Tatars, which becomes more of a consistent preoccupation in Ukrainian culture, as we will see. Guilt, meanwhile, recedes from this literary discourse. With only a few exceptions, it disappears along with the Soviet Union, the state bearing responsibility for the Sürgün and ensnaring citizens in a co-responsibility that Karl Jaspers terms political guilt. Moreover, the long-standing rhetorical focus on the Crimean Tatars’ right of return (avdet, in Crimean Tatar; vozvrashenie, in Russian; povernennia, in Ukrainian) invited a widespread impression that the 1989 Presidium decree had finally satisfied their demands, that the wrongdoing had been addressed. But the Crimean Tatar return to Crimea marked a beginning as well as an end. Repatriating in waves from Central Asia, the Crimean Tatars had to embark on a new struggle and confront a structure of local injustice that, despite dramatically changing political fortunes, had not gone away.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Crimea thus becomes widely understood as a land of three alienations. It is seen as home to returning Crimean Tatars who endure discrimination at the hands of local authorities; to ethnic Ukrainians who struggle to come to grips with their position as the titular group of a newly independent state; and to politically and culturally dominant ethnic Russians who express an insecure nationalism aligned less with Kyiv than with a collapsed imperium and its legal successor.2 This symmetrical triadic conceptualization of Crimean society – a generalization that can flatten variations and subcategories and elide other national minorities (Belarusians, Armenians) and new emergent identities (“Crimeans”) from the picture – has tended to predominate in analyses of the politics and society of post-Soviet Crimea. But it almost completely ignores the hierarchies and nested post-colonialisms that determine the interrelationships of all sides. In fact, it rarely makes reference to a colonial framework at all.3

This is a troubling silence. After 1991, like much of former Soviet territory, Crimea was a site of decolonization, a place of transition where the scaffolding of imperialism was being dismantled and remade with a view to the construction of a liberal democratic state. Much has been made of the term empire vis-à-vis the Soviet Union,4 but the question of the wholesale application of such a complex and contested term is too often a distraction. What Crimea experienced especially after 1944 was a paradigmatic project of settler colonialism. Stalin ethnically cleansed an entire indigenous population from the peninsula – roughly 20 per cent of the population at the time – and presided over an erasure of their material and symbolic traces and a rewriting of their history. He then replaced this population with tens of thousands of Russians and Ukrainians who were transplanted from outside the peninsula: a program of ethnic cloning.

These Slavic settlers appear in Aleksei Adzhubei’s memories of Crimea shortly after Stalin’s death. Adzhubei was Khrushchev’s son-in-law – and arguably the most prominent figure in Soviet journalism, who rose to the post of editor-in-chief of both Komsomolskaya pravda and Izvestiia. He recalls travelling to Crimea in 1953 with an anxious Khrushchev, who, not knowing how to swim, “dangled” in the Black Sea in an inflatable inner tube when he was not working.5 Crimea at this time was a “desolate” region still struggling to emerge from the crucible of war. The fountain in the hansaray, Adzhubei notes, had “no strength even to cry.”6 Transferring Crimea to Ukraine in 1954 was therefore, according to Adzhubei, a “business transaction” (delovaia tekuchka) directed toward its economic development, a response to the decay and stagnation under Russian SFSR administration that Khrushchev had witnessed personally. At one point, Adzhubei remembers how desperate “settlers” confronted Khrushchev about the need for more material assistance. “The settlers for the most part came from Russia,” writes Adzhubei, before making a critical clarification. “I write ‘came from’ now, but they shouted, ‘We were sent here’ [nas prignali].”7 Unlike the North Caucasus, which saw Chechen and Ingush deportation survivors return in 1957, the settler colonialist project in Crimea was left to harden for nearly half a century, offering the light of myth of a Soviet “paradise” to a Slavic majority but obscuring clear view of its nature like translucent stone.

When the return of the Crimean Tatars began to upset this myth, Crimea became a paradox: a site of decolonization active in the reinscription of patterns of colonial dominance. On the one hand, there was state support for programs aiding the Crimean Tatars in their return. Struggling with poverty and hyperinflation, Kyiv allocated in the first decade of Ukrainian independence the equivalent of over USD 140 million from the state budget for Crimean Tatar resettlement, and Turkey pledged in 1994, for instance, to build one thousand new homes for Crimean Tatar returnees.8 (By contrast, the legal successor of the Soviet state responsible for the original crime – Russia – paid nothing at all.) On the other hand, there was a rebirth of settler colonial practices on the peninsula that diminished such attempts at historical redress. Local elites consistently stymied efforts to secure proportionate political representation for the Crimean Tatar returnees, who endured inadequate housing, high unemployment, and police harassment. The fates of these families were determined, as Constantine Pleshakov puts it, “arbitrarily and meanly.”9 In 2007, after hundreds of Ukraine’s Interior Ministry forces had been used to destroy Crimean Tatar cafés on Ai-Petri peak, President Viktor Yushchenko’s Our Ukraine party openly accused Crimean authorities of a “discriminatory attitude toward repatriated Crimean Tatars” and a “selective application of the law.”10

Chauvinistic rhetoric was not uncommon. In a widely publicized diatribe in the Russian nationalist newspaper Krymskaia pravda, Russian science fiction writer Natalia Astakhova mocked the Crimean Tatars for their activism, for their indigenous resistance: “Since their return, they have done nothing but protest – as if it were their national profession,[11] their very way of life – picking at wounds, inciting resentment and hatred, rocking the boat we are all in.” She turns to address the Crimean Tatars directly, ridiculing them for their “greasy cheburek, sticky baklava, and stale kebabs”: “Really, what has been taken from you? What did you leave behind? And what remains of you here: pitiful shacks? […] The land, the sea, the wine, the mountains, the orchards, the vineyards, the cities, the villages – nothing escapes the web of your claims, everything is either ruined, plundered, or contaminated by the impurity of your thoughts. Only the sky remains. But then the cry of the muezzin penetrates it, blocking all the other sounds of a previously peaceful life.”12 Such taunting, Islamophobic screeds call to mind Albert Memmi’s observation in The Colonizer and the Colonized that “the colonialist […] devotes himself to a systematic devaluation of the colonized. He is fed up with his subject, who tortures his conscience and his life. He tries to dismiss him from his mind, to imagine the colony without the colonized.”13

For Memmi, this aggressive attempt to erase the colonized native from view – to condemn him for his grievance and then “dismiss him from the mind” – is a function of a system indiscriminate in its corrosive effect. “Colonization distorts relationships, destroys or petrifies institutions, and corrupts […] both colonizers and colonized.”14 Our prevailing reading of post-Soviet Crimean politics and society according to a regional interethnic paradigm consumed by a negotiation of interests – rather than according to a decolonization paradigm concerned with transitional justice and intergroup reconciliation – has neglected to account adequately for the structural echoes of the colonial system. More importantly, this conventional wisdom has impeded our ability to make historical parallels and learn from other cases of settler colonialism around the globe – from the United States to Australia – and to foreground the use of tested mechanisms of restorative policy: official apology, truth commissions, and electoral quotas. In other words, Ukraine never had a coherent strategy for Crimea, and a blindness to the history and legacy of settler colonialism is part of the reason. This blindness also prevented us from noting that in 2014 the Russian Federation became not only the first European country since the Second World World to annex another European country’s territory by force, but also the first successor of a modern empire to take back a former colonial possession.

Crimea therefore has not had a “Crimean Tatar problem,” as the unfortunate turn of phrase goes. It has had a festering post-colonial problem. Devoid of a conscious, structured approach to decolonization, politics in Crimea in the post-Soviet period was highly inconsistent and haphazard, an exercise in putting out fires through elite bargaining and “multi-vector” negotiation.15 Kyiv juggled balls in an earthquake, developing state institutions amid severe economic crises across the country while contending with repeated threats of Crimea’s secession between 1991 and 1995. Often Kyiv aligned with the Crimean Tatars, who were frequently referred to as “the greatest Ukrainians in Crimea.”16 Sometimes, as in 1998, when roughly eighty thousand Crimean Tatars were made ineligible to vote in parliamentary elections, Kyiv abandoned them in order to appease the dominant majority.

A silence on the matter of decolonization similarly overshadowed Crimea’s post-Soviet cultural landscape. As a consequence, it became a forest of bilateralisms or, to mix metaphors, a room of two-legged stools. Ground-breaking Russian novels like Vasily Aksenov’s Ostrov Krym (The Island of Crimea), published abroad in the 1980s but widely circulated in Crimea the 1990s, reimagined relations with the Crimean Tatars but effaced Ukrainians from view. A utopian project called “geopoetics,” meanwhile, revelled in Russian and Ukrainian interliterary connections but rarely integrated Crimean Tatar writers into the process, taking the elevation of Crimean place over Tatar personality to new theoretical heights instead. Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar writers, for their part, engaged in a concerted search for a “practical past” and for resilient narratives of solidarity outside the chronological frame of empire. As we will see, this renewed Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar encounter is one of the most fascinating, and potentially transformative, cultural developments in the region of the Black Sea.

On the other shore, Turkish writers in the post-Soviet period saw not selective affinities on the peninsula but a disturbing stasis of alienation and oppression, with Crimean Turks caught in a perpetual loop of victimization. In the pulp-fiction novel Kırım Kan Ağlıyor (Crimea in agony, 1994), for instance, Crimean Tatar patients at a Simferopol hospital languish at the hands of NKVD “vampires,” one of whom bears the moniker “The Executioner” (Cellat) owing to his thirst for blood.17 Plot lines are recycled and stereotypes perpetuated in a never-ending Cold War. Indeed, for pan-Turkist poets like Yücel İpek, the dissolution of the Soviet Union brought nothing new to Crimea and the Crimean Tatars. “Russians have gone, Ukrainians have come,” he writes in 1998, “but what has changed?” (Rus gitti, Ukraynalı geldi, değişen nedir?)18

1.

In the world of Vasily Aksenov’s Ostrov Krym (The Island of Crimea), everything has changed. Originally published by Ardis publishing house in tamizdat in 1981, the novel was serialized in the journal Yunost (Youth) as the Soviet Union collapsed. It became a literary sensation in the 1990s, especially in Crimea itself, where it seemed that everyone had a well-worn copy. Ostrov Krym is a work of “allohistorical” fiction – an imaginative exercise in alternative history – which envisions the peninsula as an island and dramatizes the end of the engagement between the White Army and Red Army in 1920 as a kind of Jonbar hinge, marking a point where time moves along a new diachronic trajectory.19 Secured and fortified by the White Army, Crimea breaks free from history to become a thriving capitalist and cosmopolitan Taiwan off the shore of a Communist giant. Aksenov’s main protagonist, the hedonist and ultimately naive media magnate Andrei Luchnikov, seeks to join Crimea to the Soviet Union in a movement called the “Union of Common Fate.” His success ends with a Soviet invasion – and with a loss of a grip on his own sanity.

Aksenov’s Crimea, of course, is a place where Stalin’s ethnic cleansing and discursive cleansing of the Crimean Tatars have not occurred. The Crimean Tatars populate the island alongside Russians, Italians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Turks, and even descendants from officers of the British navy. Crimean Tatar personality is very much alive in Aksenov’s kaleidoscopic Crimean place: their language pushes Coca-Cola products on billboards, while their words pop up in a creole dialect unique to the island.20 Atats – a portmanteau of ata (Crimean Tatar) and otets (Russian) – means “father,” for example.21 A television broadcaster shoots the breeze in Crimean Tatar alongside counterparts who use Russian and English, “interrupting each other with smiles.”22 The smell of Crimean Tatar food wafts through bazaars in Bakhchisarai and, notably, in “Karasubazar,” which has not been ascribed the post-1944 toponym Belogorsk.23 Even Soviet authorities hatching post-annexation plans refer to Crimean Tatars as Crimea’s “indigenous people” (korennoe naselenie).24 It is a surreal, heart-breaking fantasy.

When the fantasy turns to tragedy – as Crimean residents look on in horror as Soviet forces mount an aggressive invasion of a peninsula that is ready to welcome them without one – it is a Crimean Tatar character named Mustafa who gives the feckless Luchnikov his comeuppance toward the end of the novel. “To hell with the Russians,” Mustafa shouts at him. “You are all bastards! I am a Tatar! […] Know that I am not spitting in your face, only out of respect for your age. I respect in you nothing else.”25 Aksenov’s counterfactual flight of fancy ends on a decidedly ominous note, in a “union” between Crimea and the Soviet mainland that spells a kind of spiritual doom. In 2014, Sergei Aksenov – the once marginal, ironically named Russian nationalist who manoeuvred to the centre of the Kremlin’s annexation drama – clearly had not understood the book’s conclusion when he boasted that he was trying to realize the “second part of the novel.”26

Like Roman Ivanychuk (chapter 5) and Cengiz Dağcı (chapter 6), Vasily Aksenov (1932–2009) mines the past to reassert a bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality, but his allohistory makes a plaything out of our logic of cause and effect and even linear time itself. In this way it feels peculiarly present and alive, only slightly beyond our reach. With the collapse of the Soviet Union prompting a rethinking of the very concept of the end of history, the wild popularity of Aksenov’s novel was therefore no accident. But a curious erasure also haunts the book. For all its linguistic eclecticism and carnivalesque displays of ethnic diversity, there are no Ukrainians in the novel at all. They are not included in its parade of national groups, nor are they among its dramatis personae. It is a curious exclusion. In Liudmila Ulitskaia’s Medeia i ee deti (Medea and Her Children, 1996) – an intricate novel set in Crimea and alive to its rich, complex ethnic inheritance and to the tragic consequences of Stalin’s Crimean atrocity – Ukrainian characters may also be out of sight, but they only seem off stage.27 Ulitskaia peppers the margins of her family novel with signs of Ukrainian life: items of clothing are “Ukrainian”; summer homes are “cosy in a Ukrainian way”; the namesake of the popular Soviet Charcot water therapy is humorously mistaken for a Ukrainian (“Sharko”).28 But in Ostov Krym, the absence of Ukrainians is conspicuous and total, suggesting that the cosmopolitanism of Aksenov’s alternate vision of the peninsula had its limits.29

In the 1990s, Aksenov was invited to become honorary president of an ambitious Bohemian collective called the Crimean Club. Led by avant-garde Dzhankoi-born Russian poet Igor Sid (a contraction of the Ukrainian surname Sidorenko), the Crimean Club professed an intention to depoliticize Crimea and turn it into nothing less than a “world cultural training ground,” a nerve centre of cultural exchange and collaboration.30 Its seemingly self-serious motto – axis aestheticus mundi Tauricum transit (the axis of art passes through Crimea) – is actually a manufactured Latin axiom passed off as wisdom from “Biberius Caldius Mero,” a mocking nickname given to Emperor Tiberius Claudius Nero for his devotion to wine.31 Sid (b. 1963) is a prodigious impresario, and soon Aksenov found himself participating in his literary happenings on the islet of Tuzla, which is suspended like a filament of sand amid the Strait of Kerch separating the Crimean peninsula from the Russian Federation.

With the Crimean Club, Sid sought to remake the peninsula in the form of Maksimilian Voloshin’s home in Koktebel, as a waystation for artists and intellectuals of diverse modes and genres. He vigorously promoted Ukrainian-Russian literary socialization and interaction, translating, for instance, the work of Yuri Andrukhovych and Serhiy Zhadan. (Zhadan describes Sid as “a man of the nineteenth century, for whom there is no clear division between poetics and, say, botany.”32) For over two decades Sid’s Crimean Club hosted countless performances, installations, conferences, and readings in Moscow, Crimea, and even Madagascar. These events manifested a “certain insanity of discussion” and even proudly insisted that participants agree to one simple idea – namely, that Crimea was the centre of the world.33

Yet there is barely a whisper of a presence in this world of Crimean Tatar poets or prose stylists. For Crimea’s most active and audacious international artistic initiative, Igor Sid’s Crimean Club has placed relatively little emphasis on the culture of Crimea’s indigenous peoples. Crimean Tatar writers feature almost nowhere in its program. A driving factor behind this absence is a notion called “geopoetics,” which Sid prominently positions as a vague guiding principle. Geopoetics is, in his words, the “management of […] a topographical-territorial myth” (upravlenie […] landshaftno-territorialnim mifom).34 Its conceptual opponent is geopolitics. “The age of politicians is over,” proclaims literary scholar Mikhail Gasparov in one of Sid’s emblematic epigraphs, “and in the place of geopolitics comes geopoetics.”35

Geopoetics is the apogee of a process that we began to trace in the Russian literary tradition in chapter 1: the elevation of Crimean place over Tatar personality. It turns its back on the idea of territorial-based sovereignty, of a bond of a particular people to a particular space. It responds to imperial colonialism and to the claims of the colonized by overlooking them in the sway of utopian alternatives. “The Crimean version [of geopoetics],” writes Sid, “affirms the transition of humankind from the era of power ambitions to the era of creative ambitions.”36 But an era of creative ambitions can be poor refuge for those with little secure political power. Holding fast to the concept of an ancestral homeland was precisely what powered the Crimean Tatar movement in the Soviet Union and informed its campaign for a restitution of rights, land, and respect after the Soviet collapse. Abandoning geopolitics for projects like geopoetics, in other words, was a luxury they could not afford.

2.

Both Igor Sid and Serhiy Zhadan participated in a Kyiv roundtable discussion on the cultural dynamics of Crimea in May 2008. Zhadan (b. 1974) is one of the most fascinating phenomena of contemporary Ukrainian culture – a Ukrainian-language poet, novelist, and rock performer from eastern Ukraine who defies easy categorization. “When Sid told me about the idea of this roundtable,” Zhadan said, “he asked me to suggest Ukrainian writers who write about Crimea.” Zhadan explained that it was not a straightforward task. “Ukrainian writers, like the majority of the population of Ukraine, still consider Crimea not as a part of Ukraine but as a kind of tourist zone from which one comes and goes.” The problem, he said, was “an unspokenness, an unwrittenness of Ukrainian literature” vis-à-vis Crimea (neozvuchenist, nepropysanist ukraïnskoï literatury). Zhadan concluded, “I do not know what to do with it.”37

But Sid had an idea. Reflecting on Zhadan’s remarks, he writes, “One of the central reasons why Crimea is often perceived as something alien [nechto chuzherodnoe] in the Ukrainian imaginary is the connection of the peninsula with Russian history and culture over two centuries.”38 Sid therefore counsels Ukrainian writers to generate more literary texts about Crimea and its inhabitants. “Writers build better bridges than politicians,” he declares. It is sage advice. But unwittingly or not, Sid also presumes something about literary representations and their role in geopoetics: they are seen as agents of possession. To make Crimea one’s own – not something alien – is to write about it. Two centuries of Russian poetry and prose about Crimea, he suggests, had the benefit of making it understandable to Russian readers as uniquely theirs.

While enlightening, the roundtable contributions by Zhadan and Sid also betray a “reverse hallucination,” a failure to see what is there.39 It is not only a failure to recognize a sustained tradition of Ukrainian writing about Crimea since the nineteenth century, as we have seen in chapters 2 and 5, or a failure to consider the question of Crimean Tatar literature alongside or within the Ukrainian tradition itself. It is also a blindness to Ukrainian writing in Crimea – poetry and prose by Ukrainians for whom Crimea is not a tourist zone but home. The community of artists who wrote from this perspective was a self-described “minority within a minority,” but it was an active one.40 Only a few years before the Kyiv roundtable, in fact, the Simferopol-based poet and translator Danylo Kononenko compiled a three-hundred-page anthology of works by contemporary Ukrainian writers in Crimea.41 It was subsidized by the Ukrainian state; three thousand copies were printed. The texts in the compilation are largely averse to formal experimentation and preoccupied with the celebration of national tradition, but they nonetheless testify to committed activity on the part of a Ukrainian literary community in Crimea that is often counted out or overlooked, even by intellectual circles in Kyiv.

In 1992 Kononenko had challenged the passivity of his “Crimean brothers” and called on them to make the realization that “you are home” in the first issue of Crimea’s Ukrainian-language newspaper, Krymska svitlytsia.42 Assuming a full-throated Shevchenkian posture, he implores them: “Why do you shrink away as if there are none of you on this land?” His rallying cry helped spark creative expression that has been especially steadfast in its devotion to the cause of Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar solidarity. In “Povernennia” (The return), for example, Kononenko’s lyrical persona wanders through makeshift Crimean Tatar settlements made up of “temporary shelters” (tymchasivky) and welcomes them back to the peninsula. “How much suffering, humiliation, and hardship must these people endure,” he laments:

…Перетерплять все, перебідують,

Лиш би жити на землі батьків!43

(They bear everything and suffer all over again,

Just to live in the land of their ancestors!)

Orest Korsovetsky, a veteran of the Second World War whose early work was recommended to the editor of the journal Dnipro by Maksym Rylsky, likens the Crimean Tatar return to a victory of truth and justice over lie and illusion:

Міражі розпливаються,

І йдуть татари, йдуть.

Верта-а-ються! Верта-а-ються!

Легка-хай-буде-пу-у-ть!44

(The mirages are lifting,

And the Tatars are coming, they are coming at last.

“They are re-turn-ing! They are re-turn-ing!

May the journey be not burdensome!”)

Such Ukrainian poetic expressions of solidarity with the Crimean Tatars were reciprocated. A striking example is “İqrarlıq” (Declaration), written by Samad Şukur in 1993:

Ukraina – qardaşım, soyum!

Sensiñ doğmuşım.

Eger maña rastkelgen

Duşman

Saña apansızdan

Intılsa,

Meni çağır,

Men sağım

……… .

Seniñ serbest

Olmañ içün

Men ölümge de azırım!45

(Ukraine – my brother, my kin!

I am your family.

The enemy

Suddenly sets

Upon you,

Call on me,

I am by your side

……………

For your freedom

I am prepared to die.)

These works of literature were only a small part of a much broader cultural and academic campaign to fortify a post-Soviet Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar alliance. Translation projects proved an especially resilient mortar, with the team of Yunus Kandym and Mykola Miroshnychenko publishing a series of massive bilingual collections of Crimean Tatar poetry and prose. They helped build on practices of national metaphorization and deepen a solidary bond that has defied socio-cultural gravity, surmounting centuries of mutual stereotyping and historical antagonism. Even today, in some currents of Ukrainian cultural memory, stories of Crimean Tatars raiding Ukrainian homes for slaves in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have had lasting currency.46 In some currents of Crimean Tatar cultural memory, meanwhile, stories of Ukrainians participating in the dismantling of the Crimean Tatar khanate in the eighteenth century and in the dispossession of Crimean Tatar families in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have left a deep scar. Yet the modern Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar alliance has succeeded in overcoming such stories by excavating and promoting, inter alia, a “practical past” of solidarity in their stead.

Hayden White adapts Michael Oakeshott’s concept of practical past to refer not to history ensconced in the archive but to history offering “guidelines for acting in the present and foreseeing the future.”47 For the project of post-Soviet Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar solidarity, this practical past is seen at first to exist entirely outside the Russian colonial frame, in the seventeenth century of alliance and co-operation between the khanate and the Zaporozhian Cossacks. This is the period of the poetry of Canmuhammed (chapter 3) and the period at the centre of the prose of Roman Ivanychuk in Malvy (chapter 5). It has become the subject of novels, films, and even comic books written by authors who see Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars as bound so tightly in metaphorical relation that even their national symbols – the trident and the tamğa – are noted for mirroring each other.48

After 1991 this Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar discourse of encounter also evolves into a discourse of entanglement, of hybridity, interpenetration, and even transfiguration. As we will see in the next chapter, it evolves further into a discourse of enclosure after the 2014 annexation. One of the agents of this entanglement is Şamıl Alâdin, whom we met in chapter 3. Alâdin adapts Canmuhammed’s seventeenth-century poem about the Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar campaigns against Poland, into a novel entitled Tuğay-Bey, which he worked on until his death in 1996. Published posthumously in an incomplete form in 1999, the work stages a cultural and even spiritual intermingling of his Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar heroes.

Alâdin’s Tuğay-Bey seeks to transport the reader to a period when a Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar alliance was actively changing the very map of Europe. Guided by a first-person narrator named Sahib, who identifies himself as an aide to Tuğay-Bey, the novel begins as a journey through a vibrant, diverse Crimean Tatar society under the Giray khans. Rendering snapshots of such diversity in prose was one of Alâdin’s literary passions, evident in a companion historical novel entitled İblisniñ ziyafetine davet (The devil’s invitation to the feast, 1979), which finds inspiration in the life of Üsein Şamil Toktargazy, whose work was featured in chapter 2. Alâdin’s Toktargazy travels across Crimea against the backdrop of bustling markets and ivy-covered minarets, from the capital, Bağçasaray, to the cosmopolitan Qarasuvbazar (Karasuvbazar, so cosmopolitan that Ismail Gasprinsky called it “Karasu-Paris”).49 His itinerary plots the coordinates of a diverse, contested, but fully coherent Crimean Tatar society at the twilight of the Russian Empire.50

In Tuğay-Bey we encounter this robust society in the seventeenth century under threat from abroad. The novel’s centrepiece, at least in its incomplete form, is an elaboration on Canmuhammed’s depiction of the Ukrainian entreaty to Khan İslâm Giray for military assistance. In his version of the entreaty, Alâdin attends to the warm relationship between Khmelnytsky and the khan himself, who briefly focalizes the narrative and welcomes “Bogdan” [Bohdan] to this inner sanctum: “[The khan] had great respect for Bohdan’s military command and mastery. After twenty-five minutes, [Khmelnytsky] entered the khan’s sacred reception quarters, and İslâm Giray greeted him warmly. The hetman respectfully responded to him in the Turkish and Crimean Tatar languages [türk ve tatar tillerinde cevap berdi].”51

Alâdin casts such linguistic exchanges not only as evidence of mutual respect but also as testament to a deeper mutual intelligibility and intersection. Between the leaders of the Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian peoples, no translation is needed.52 Here, for instance, is Khmelnytsky’s direct plea to the khan for military aid:

İzzetli ve saadetli İslâm Girey han! Ukraina halqı Polonya esareti altında iñlemekte. Adamlar pek ezildi […] aç, çıplaq qaldılar, — dedi tatar tilinde, soñra ukraincege keçti. Han getmannı tercimesiz diñledi.53

(“Venerable and blessed Khan İslâm Giray! The Ukrainian people are groaning from the oppression of Poland. The people are crushed […] hungry, naked,” he said in the Tatar language, before moving into Ukrainian. The khan listened to the hetman without translation.)

Here Alâdin echoes Canmuhammed’s source text and frames the Ukrainian casus belli as the self-defence of a “crushed,” “hungry,” “naked” victim against a foreign aggressor. He foregrounds a Crimean Tatar khan and a Ukrainian hetman who understand fluently the language of the other. Their mutual comprehension extends beyond Realpolitik into the realm of speech and identity. In fact, at one pivotal moment, it produces an almost spiritual confusion of their languages and cultures. To underscore the purity of his intentions, Alâdin has Khmelnytsky swear before the khan in the name of Allah in the Ukrainian language before kissing the Qur’an three times. From this moment, a solidary bond between Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars is forged. “At a time of such tense circumstances, Ukrainians and Crimeans Tatars should be united [qırımtatarları ve ukrainalılar birlik olmaq],” remarks Alâdin’s narrator. “The two peoples […] should desire to be always at the ready to help each other.”54

This theme of cultural and spiritual intermingling is taken in novel directions by the Ukrainian filmmaker Oles Sanin (b. 1972), whose first feature film, Mamai (2003), counterposes the very foundations of national identity with what Ernesto Laclau calls an “empty locus,” “a formation without foundation.”55 Laclau likens the empty locus to a horizon, a field of possibility and potentiality that can orient forms of human organization without binding them to the same points in space. For Sanin, this empty locus is incarnate in the mysterious figure of the Cossack Mamai.

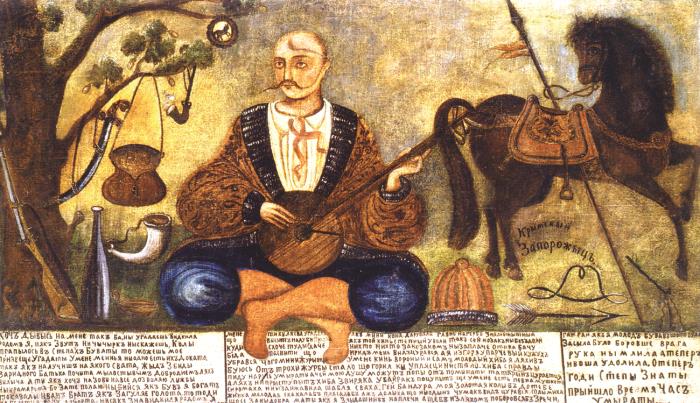

Ubiquitous in Ukrainian art from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, the image of the Cossack Mamai is at once familiar and strange. With a horse and sword by his side attesting to freedom and martial prowess, he wears a zhupan (Cossack overcoat) and displays the trademark oseledets, the long lock of hair on an otherwise shaved head (figure 8).

8. The Cossack Mamai (c. early nineteenth century, artist unknown)

Yet this is not Gogol’s belligerent Taras Bulba, Kulish’s Byronic Kyrylo Tur, or one of Repin’s rakish Zaporizhians. The Cossack Mamai sits in the Turkish bağdaş (cross-legged) position, projecting a serenity like Buddha under the bodhi tree, and bears the name of a fourteenth-century khan of the Golden Horde. He strums a lute or a bandura in solitude, his eyes passive and capacious, a site of memory of an era somehow both distant and close at hand.56

For Sanin – who considers Sergei Paradzhanov, Yuri Illienko, and Leonid Osyka his artistic forebears – an image like the Cossack Mamai bears revelatory poetic potential when translated into film. Mamai is accordingly a feast for the eyes, a constellation of images rife with ethnographic detail in which the cinematic frame becomes a startlingly fresh and vivid still-life tableau: incandescent lovers shimmering in the moonlight, a woman’s haunting eyes emerging from niqab, and men caked in a white dust scaling a pale cliff. Yet the privileging of these images and sequences – which are “more juxtaposed than connected”57 – confuses an ambitious triadic narrative that, according to Sanin, is meant as an act of recovery of an oft-forgotten history of entanglement between the Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar communities.58

Sanin weaves together three distinct yet interrelated plot lines, the first adapted from the Ukrainian epic tradition, the second derived from Crimean Tatar folklore, and the third conceived by the filmmaker himself.59 The first plot is based on “Duma pro trokh brativ azovskykh” (A duma [a Cossack lyrico-epic folk poem] about three brothers from Azov) in which two brothers, fleeing from Crimean Tatar captivity on horseback, abandon their youngest brother who is on foot.60 According to Sanin, the second is inspired by a Turkic legend about the search for the Golden Cradle of Genghis Khan, a talismanic object whose disappearance, like that of the Roman aquila, portends death and destruction.61 In Mamai these two tales are conflated into a story that pits the three Crimean Tatar brothers, seemingly empowered by the Golden Cradle, against the two escaped Cossacks, who become increasingly regretful of the abandonment of their brother. A pursuit across the steppe ensues. Sanin supplements this chase narrative with a romance between the two protagonists who have been deserted by these warring sides – the Cossack brother left for dead and Amai, the sister of the Crimean Tatar brothers, who discovers and revives him.

As in Ivanychuk’s Malvy, the Crimean Tatars and Ukrainian Cossacks are largely at odds with one another in the film. One side hunts the other. There is ample dramatic irony in the presentation of this antagonism, however, because the spectator observes a strong symmetry between those who hunt and those who flee, a symmetry that neither side can see. Sanin ensures that the actions of the Cossacks are mirrored in those of the Crimean Tatars: when the former ride, pray, emote, or fight, so do the latter. To underscore their similarities, visual and aural features of the film simulate a slippage between the Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar worlds from its very outset. The breve of the iot in the film’s title heading is rendered with a cross and then, subtly, with a crescent. Interspersed among the opening credits are stills of Cossack Mamai genre paintings and Crimean Tatar calligraphy, of abstract Crimean Tatar tamğalar (insignias) and aging manuscripts of Ukrainian dumy. The film’s score, meanwhile, incorporates elements of both the Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar musical traditions, building to a scene featuring asynchronous sound in which the two styles of music replace the words exchanged in a passionate argument between Amai and the abandoned Cossack brother, who speak in a language the other does not understand.

Mamai was shot on location on the Crimean steppe, and the historically porous region is a critical character in the film, a vast and open land where no man-made enclosed space can be found. There are no towns or villages, no farms or fortresses, no churches or mosques; there is only Amai’s barren, roofless homestead covered by a loose patchwork of tattered tarps and Kilims. Her home evokes the so-called samozakhvaty (“self-seized” shanties) occupied by many Crimean Tatars in the post-Soviet period. The film’s elaborate plot lines and pregnant images build to a moment when the abandoned Cossack brother literally becomes the open, “empty” figure of the Cossack Mamai. After Amai rescues him and cleanses his face of hardened white dust, naming him “Mamai,” the spectator watches as the young Cossack crafts a lute while enveloped in a nocturnal haze. Sounds of distant voices, alternately diegetic and extradiegetic, give him pause, and he looks up with curiosity and trepidation before sitting bağdaş with his instrument. He becomes the Cossack Mamai, and in the best traditions of Ukrainian poetic cinema, the film becomes a genre painting (fig. 9).

9. Mamai, directed by Oles Sanin (2003)

To emphasize the profundity of his protagonist’s transformation, Sanin splices into the scene images of painting inscriptions, one of which reads: “Though you endeavour to look upon me, you cannot divine my origins; of my name you know nothing at all.” This “mamaification” is brief and devoid of elaboration, a moment in which a Ukrainian Cossack becomes a vague emblem, an “empty locus.” Sanin offers us a provocative filmic meditation on the position of Mamai as a marker of an identity formed by interethnic, cross-cultural encounter and the vast openness of the steppe. As the director himself observes, “in Turkic languages, ‘Mamai’ means ‘no one,’ ‘the impossible,’ ‘he who is without a name, without the word.’ This is emptiness itself.”62

3.

Mamai marked the silver screen debut of Akhtem Seitablaiev (b. 1972), an actor and director who plays one of the wayfaring Crimean Tatar brothers in Sanin’s film. Born in exile in Tashkent to parents who survived the deportation, Seitablaiev settled in Crimea after 1989. He has become one of contemporary Ukraine’s foremost actors and celebrities since his appearance in Mamai. In recent years he has also won renown as a director with a rare touch for the Hollywood-style blockbuster. One of them is Khaitarma (2013), which centres on a week in the life of legendary Second World War pilot Amethan (Amet-Khan) Sultan, whose standing as a two-time Hero of the Soviet Union hangs in the air of the film as damning refutation of the accusation of mass treason behind Stalin’s Crimean atrocity. The film’s sequence of events culminates in the night of 18 May 1944, when Seitablaiev’s Sultan, on leave from his military base to visit his family in Alupka, witnesses the deportation operation in horror. What begins as an encomium to his heroism ends as a nightmare of his heroism, as he must flee from agents of a state that he has not only defended but monumentalized with his bravery. Not unlike Andrzej Wajda’s Katyń (2007), Seitablaiev’s Khaitarma concludes with an extended representation of the atrocity in all its senseless cruelty.

Khaitarma had its Turkish premiere in Eskişehir, the 2013 “Cultural Capital of the Turkic World.” The event was attended by a group of Turkish politicians and dignitaries, testifying to the significant standing of the transnational Crimean Tatar community in Turkey after 1991.63 No longer are the Crimean Tatars considered objects of “passivity” or “indifference” in Ankara’s corridors of political power. They have been subjects of often intense domestic political discussion and a lead agenda item in Turkey’s evolving strategic relations with independent Ukraine. In 1998, for instance, former Turkish president Süleyman Demirel visited Crimea and gave a stirring speech on the grounds of the hansaray, declaring, “We have come to support you – our neighbours and good friends – in the new historical role placed on your shoulders as loyal citizens of Ukraine, both in the strengthening of the independence, territorial integrity, and stability of this young state and in the rooting of your people, once again, in the ancestral homeland.” He added, with a note of reassurance that seems naive today: “The past is past. Put your fears aside.”64

High-level visits of Turkish officials to Crimea have been frequent over the past decade. In 2011, for instance, Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu helped bring the remains of Cengiz Dağcı back to the peninsula for burial. Dağcı had died in England, having never returned to his homeland, even for the second Qurultay to which he was invited in 1991. “When the news of Cengiz Dağcı’s death reached me,” Davutoğlu said, “suddenly I thought of all the novels I had read in middle school and high school: Onlar da İnsandı, O Topraklar Bizimdi, Yurdunu Kaybeden Adam, Korkunç Yıllar.” Dağcı’s memorial was a uniquely regional event. As Davutoğlu declared, it marked “the meeting of two sides of the Black Sea [Karadeniz’in iki yakasının buluşmasıdır], the meeting of Ukraine and Turkey, which will always remain friends.”65

Like his erstwhile foreign minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has repeatedly spoken of the Crimean Tatars as a “bridge” joining Turkey and Ukraine.66 In May 2013 he counselled Mustafa Dzhemilev to strengthen this bridge by working more closely with (disgraced former) Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych. It made good political sense, Erdoğan advised, to have the Mejlis represented in Yanukovych’s administration before the 2015 Ukrainian presidential election. Dzhemilev’s response to the Turkish prime minister was a blend of principle and prophecy. He explained that the democratic structure of the Mejlis – and the Qurultay, which elected its members – was not conducive to such political volte-face. In any case, he seemed to imply, the potential price of such co-operation would be too high. Dzhemilev then offered Erdoğan something of a political forecast. “As far as the 2015 elections bothering Yanukovych so much,” he said, “he had better hope to God he remains president until then.”67 Yanukovych would flee from office within a year.