Isn’t a stereotype a still image? Do we not have a dual relationship with platitudes: both narcissistic and maternal?

—ROLAND BARTHES, “UPON LEAVING THE MOVIE THEATER”

The stereotype can be evaluated in terms of fatigue. The stereotype is what begins to fatigue me.

—ROLAND BARTHES, ROLAND BARTHES

In his film Die Koffer des Herrn O. F. (The Suitcases of Mr. O. F., Germany, 1931), Alexander Granowski presents an ironic fairy tale about the modern capitalism of the era and reflexively touches on the world of cinema. The director of a fictive film company explains his business strategy: “Problems make you go broke. Comedies bring dividends.… Why are we a world-class company? Because we produce comedies! I beg of you!” A song follows, sung from off-screen, as a coloratura in the style of an operetta aria referring to the popular film genres of the period. “Sound film comedies” and “sound film operettas” (Tonfilmkomödien und Tonfilmoperetten, the German counterparts to the American film musical) always depicted the complications of a love story, and they did so with frequently recurring narrative and visual motifs. This is alluded to the lyrics from Granowski’s film:

He loves,

she loves,

we love,

they love,

they all, all, all, all love.

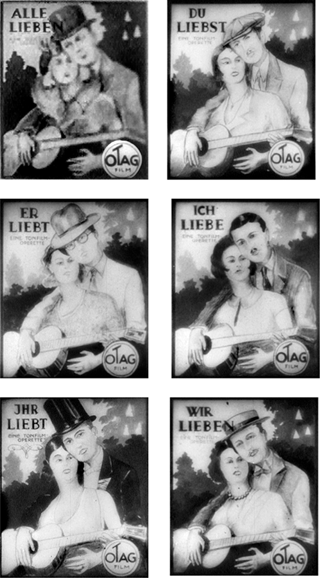

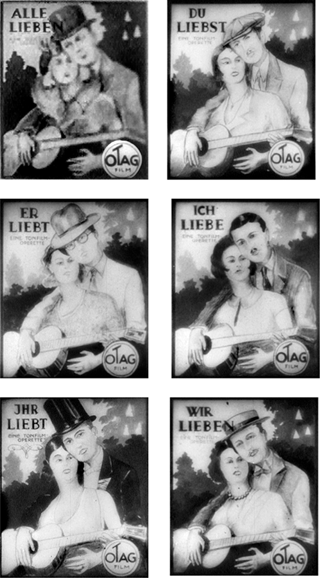

While the song is sung, a series of six fictive film posters with extremely similar compositions appears on screen. All show an embracing couple from the waist up, the woman always holding a guitar. The motifs differ only in superficial detail, mostly in a different hat or pair of glasses.

The effect is immediately repeated, whereby the song, now sung to a marching rhythm, refers to the military comedies (Militärschwänke) popular in Germany at the time.

Barracks air,

Barracks smell,

Barracks magic.

Marching is such fun.

Another series of posters appears, each depicting an officer and a woman with a horse. These images too are almost identically composed and vary only in a few minor details, most obviously in the form of the helmets.

The current of filmic self-examination running through this sequence widely epitomized the contemporary discourses on cinema of German film critics and theorists around 1930. In this example, a motion picture from the period addresses a characteristic trend of its own medium. Only peripherally does it concern a satirical take on the cinematic glorification of military ritual, which was also ridiculed by the progressive film criticism of the time. First and foremost, the sequence from Granowski’s film caricaturizes the stereotypization of film. This is perhaps the first time in the history of film that a motion picture explicitly conducts a brief reflexive discourse on this theme, which constitutes the main topic of this book.

Incidentally, in its satirical display of stereotypes the film employs the device of synchronic, intratextual serialization, a standard technique used for visual and self-referential representations of the phenomenon. This will be described in more detail further on.

Not even a decade prior to Granowski’s persiflage of the film business’s repetitive and reductive compulsions, in the first half of the 1920s intellectual aficionados of cinema such as Béla Balázs had associated the medium with very different hopes and utopias. Euphoric ideas about the future of film as art were based on the idea that cinema was destined to cultivate a new visual culture: the long-deplored conventionality and abstraction (arising therefrom) of the culture of language and writing—asserted under the banner of language skepticism (Sprachskepsis)—could be overcome by the visual and concrete medium of film.

Toward the end of the decade, such euphoria had given way to disenchantment, including among film critics. Intellectual observers now became aware of the medium as an all the more powerful agent of the conventional. They now realized that conventionalization of cinema did not fail to affect the sphere of gestural and visual expression. Through the constant repetition of patterns reduced in complexity it standardized the imaginary of large masses of people, even on an international scope. Cinema tended to create globally widespread visual imaginations and forms of expression.

FIGURE 1 Series of fictional film posters from the motion picture Die Koffer des Herrn O. F. (The Suitcases of Mr. O. F., Alexander Granowski, Germany, 1931).

Fixed schemata were now observed everywhere in the worlds of narrative and in their visual composition. They reoccurred in extended series of films and were progressively automatized and conventionalized, thus becoming intersubjectively established. This concerned patterns of plot structure (including the macro- and microstructures of narrative) and character construction as well as patterns of acting, visual style, the combination of image and music, and so on. Around 1930, the great majority of German commenters massively criticized this trend, either from the standpoint of ideological critique or, predominantly, in terms of aesthetics and style.

A major cause for these serial tendencies was soon found: film’s industrial mode of production, which was associated with the reigning capitalistic conditions of commodification and distribution. The second half of the 1920s was pervasively marked by rationalization and full industrial mechanization, and the New Objectivity blossomed in Germany. Against this backdrop, metaphors from the spheres of industrialization and mechanization were popular in cultural discourses and ultimately entered into thinking on cinema. Long before Horkheimer and Adorno criticized the “culture industry” (particularly Hollywood) and its tendency toward the intertextually and culturally conventionalized schema—the stereotype—critical observers around 1930 described cinema as a “dream factory” (Ilya Ehrenburg) and “fantasy machine” (René Fülöp-Miller) or talked about the “standardization” (Siegfried Kracauer, for example) and “Taylorism” (Willy Haas) of film, or even the “ready-made film” (Rudolf Arnheim).1

Some theorists recognized even then that the much-repeated schemata that had developed into stereotypes were not only based on the routine of cyclical production but also were repeated because they functioned so well. In other words, they were evidently (reciprocally) coordinated with the dispositions, expectations, and desires of a wide audience. With film, entertainment had finally become standardized “manufacturable goods”2 that could be traded worldwide, and “spiritual needs” could be satisfied “with a standardized article which would not only be manufacturable but which would also offer each customer something that suited him,”3 as René Fülöp-Miller concluded in 1931. In this conception, stereotypes function as audience-coordinated product standards with obvious parallels to the satirical statement of Granowski’s fictional film mogul.

During the period around 1930 when the topic of the stereotype was “discovered” by film theorists and critics, the assessment was overwhelmingly clear—and negative. The stereotype, usually described as “standard,” was considered the absolute opposite of positive critical terms such as “artistic,” “creative,” “nuanced,” “true,” “individual,” or “original.” Today, such a Manichaean view seems overly simplified, at the very least. A limited perspective, it has meanwhile become practically unacceptable.

In the media world of the early twenty-first century, the trends toward filmic—or more generally speaking, audiovisual—stereotypization and conventionalized patterns of (visually or narratively) reduced complexity have assumed such quality, quantity, momentum, and ubiquity, with corresponding schemata having taken over our imaginary worlds to such an extent, that the idea of creating films untouched by such factors seems truly anachronistic. Whereas even before film, popular storytelling was considered to great extent an art of repeating and reduced forms and also had the function of promoting popularity, in our contemporary world of media there is no form, no image, no narrative idea, and no structure that, once it has “caught on,” remains without an extended series of successors. Digital imaging pushes these trends to the extreme. Once conceived and developed at high cost, digital design schemata that produce a certain effect (for example, a dissolving figure or other transformations through “morphing”) are repeatedly employed—undergoing only superficial changes in appearance—through the use of the same software. Indeed, an aesthetic schema can even be patented and legally copyrighted via the usually extremely costly software used to generate it. Countless television channels, videos, DVDs, and multimedia applications additionally ensure the constant presence and availability of already similarly structured or even identical productions shown repeatedly.

Even singular, actual events—media images of catastrophes, terrorist attacks, royal weddings, funerals, and so on—are today, once they have initially attracted mass interest, followed by an endless succession of medial replays of all kinds, from direct recapitulations to all possible sorts of paraphrases and even fictionalized reenactments such as docudramas or major motion pictures. Usually this practice is pursued to the point of completely wearing out any original emotion. This mechanism also characterizes the stereotypization of fictional structures (especially in their late phase). Previously stirring images are transformed into mere semiotic signals, which, like hieroglyphs, now refer only symbolically and in a strangely abstracted manner to an original event, which now may be recalled by the mere quotation of fragments. With respect to the omnipresent serialization of narrative media products Umberto Eco emphasizes the sense of being transported into an “era of repetition,”4 and Roland Barthes describes the media as “repeating machines.”5

In the cinema, the audience mostly inhabits imaginary worlds whose regularity, coherence, and reductive simplicity are produced by repetitive forms that have become conventional and are used in a more or less automatized manner. Spectators of genre film or TV series are familiar with the repeating and similarly constructed figural types and stereotypical plot elements attached to them; they know the conventional type of music that is employed, when, for example, danger looms in a thriller or horror film. The audience is aware of the customary visual staging of chase scenes. It knows how a saloon is supposed to look in a Western, how aliens appear in a science-fiction world, and what kinds of rituals unfold in these locations. It also knows that it does not bode well if during an embrace one partner demonstratively stares straight ahead (in the direction of the camera) over the other’s shoulder. The audience has learned all this not through experience in their everyday lives outside the media (insofar as such an existence is still possible) but over the course of many years of spectatorship in the intertextual space of filmic imagination. The latent knowledge gained here constitutes what is generally described as “media competence.” The underlying stereotypes form and structure the intersubjective imaginary world of our time. The stereotypes of popular film therefore simultaneously become cultural signs.

Anyone making fiction films must do so in relation to current stereotypes. Those aspiring to emancipate themselves from such stereotypes and demonstratively formulate difference cannot forgo at least taking these patterns into account. Stereotypes are powerful because they are based on well-functioning structures coordinated with recipient dispositions, with previous experiences, wishes, and expectations, and these structures themselves have shaped viewer dispositions on a mass scale. Today, far more common than the attempt to demonstrate difference, however, is the ambition to use, not merely reproduce, the world of stereotypes and thus to achieve some measure of confident mastery over them. Often this amounts to simultaneously using the patterns as symbolic forms while playing with them creatively on another level. The interplay of stereotype and difference is as much of an issue in this case as emblematic or allegorical composition. The latter seems appropriate to the stereotype, but repetition successively leads to such emotional wear that, in the sense already indicated, an “abstract” perception of the given form as a symbolic entity is consolidated.

Another potential creative approach to stereotypes that strengthens their symbolic employment lies in their filmic reflection, or reflexive use of stereotypes. In this case, the film conducts more or less pronounced discourses—sometimes critical or satirical, sometimes mildly ironic or even transfiguring—about the world of stereotypes it now inverts. Originally comic or carnivalesque, this approach was later adopted by the avant-garde and is now widely established in mainstream cinema and fictional forms of television such as soaps. This particularly characterizes productions identified as postmodern. This treatment of stereotypes is part and parcel of the post-1980s TV style that John Caldwell terms “televisuality.”6

All in all, the stereotype seems to have particular significance for the age of audiovisual mass media. The latter produce their programs in historically unprecedented quantity and seriality, thus maintaining their virtually constant presence; they thereby address formerly inconceivably large and often global audiences. Processes of stereotypization are thus precipitated in large number and concentration, with a dynamic that is highly accelerated in comparison with previous societies. Furthermore, they gain an incredibly broad intersubjective base among recipients. In sum, all these aspects have inspired the idea of undertaking a nuanced, comprehensive, and detailed study of the stereotype from the point of view of film studies.

But why from the perspective of cinema? As the first audiovisual mass medium in history, film set the pace of this development, which was reflected upon by film theorists, practitioners, and critics—already before the widespread use of television and other media—in accompanying discourses. As a cultural and aesthetic institution having evolved over the course of over a century, cinema today is still affected by the various phases of intellectual response to the stereotype phenomenon, to which it presents the most diverse range of practical approaches. Thus, the general idea of this study readily presented itself: to investigate the connections among the development of the medium, stereotypes, and the mechanisms of their formation with a focus on film. This approach makes it possible to outline a paradigm of audiovisual media culture in the twentieth century.

This study will examine different aspects of stereotype and film, as reflected in the organization of the book. The initial focus of part 1 (in chapter 1) is to specify the key concept of the “stereotype” in theoretical terms. Here, one confronts the problem that the term is used in various academic discourses and thus refers to quite a diverse range of subject matter, research interests, and theoretical concepts. In psychology, the concept of the stereotype is predominantly associated with conventional images of people who belong to certain groups or classes. Situating the concept within the study of the idiom, one branch of linguistics regards stereotypes as recurrent utterances that have become conventional. In the study of literature, when the term is not primarily used in referring to the literary presentation of images of the Other (in the sociopsychological sense), it often denotes conventional patterns, for instance of style. And in art history one finds “stereotype” defined as a highly reduced, conventionalized schema (sustained in part by the imaginary) of visual representation.

Within a theory of the stereotype not strictly adhering to any of these given lines of questioning it is necessary to explore structural similarities among all of the individual concepts and circumstances while remaining acutely aware of the differences among them. One must look for similarities and links that would explain why in each case the use of the term “stereotype” is valid to a certain extent. Here important facets will be established in grouping such similarities together.

Stereotype formation is understood as a special conventionalized form of schematization. A fundamental objective of this inquiry is to comprehend stereotypization in line with pragmatics and constructivism as a process indispensable to cognition, communication, and behavior and as one that intervenes in many different levels and areas of these activities—as a “mechanism,” however, whose tendency toward stabilization always has a “downside” as well as critical issues that require a creative, self-critical, and reflected approach. Once repertoires of similarities among discourses on the stereotype have been outlined, then on this basis it will be possible within the scope of the discussion on the stereotype and cinema to widen the examination to discourses operating with other terms, including “standard,” “pattern,” “schema,” “formula,” “the formulaic,” “the ready-made film,” “cliché,” and so on, while remaining closely tied to the classical issues and concepts of stereotypes. This latter step will be essential, for one, because in contrast to theoretical discourses on film and aesthetics carried out in French, and to a certain extent also in English, in German the term “stereotype” long remained associated with the more restricted sociopsychological usage, with the above-mentioned terms often employed instead, especially regarding stylistic devices and related aspects. In sum, the aim of the approach pursued here is to free the theory of the stereotype from disciplinary constraints without leading to arbitrariness.

Chapters 2 and 3 of part 1 deal with the specific significance of the topic for film and illuminate the forms and functions of stereotypization within cinema. These sections concern a number of questions such as: How are tendencies toward stereotypization manifested in film, and in what way is this reflected on the different structural levels of the medium? How can one explain the specific origins and functions of the affinity of popular films to conspicuous stereotypes? How are film genres, including hybrid genres, to be understood on this basis? And to what extent does the concept of the stereotype provide a helpful perspective on cinematic genre theory? Also, why was the fundamental response to the stereotype among critics so vehemently negative, especially in the early German discourses on the topic?

Which brings us to another aspect, namely, the intellectual or film-theoretical discourse on the stereotypes of popular film. The present survey gives particular consideration to this topic, largely by tracing its theoretical and historical development. Part 2 provides a close examination of different historical phases of film theory’s discourse on the stereotype and its prevailing paradigms. These not only include the fundamentally critical position of classical German film theory, which emerged against the backdrop of an aesthetic rejection of all things conventional, as a legacy of both the romantic aesthetic tradition and language skepticism (Sprachskepsis). They also encompass the later appreciation for stereotypes—precisely as conventional forms with a tendency toward abstraction—within the incipient semiotic thought of the filmologists Cohen-Séat and Morin. Finally, this history also includes the postmodern, reflexive celebration of stereotypes as free-floating semantic material readily available for hybrid (re)construction.

Media-theory discourses always maintain multiple relationships to the practical media developments of their periods. It is not necessary to subscribe to all of New Film History’s lofty demands when assuming that the historical study of film theory may transcend a purely theoretical framework. Cross-references between the film-theoretical discourse on the stereotype and different filmic uses or the practical treatment thereof, and the exploration of interactions between them, are programmatic for this study, regardless of their theoretical or theoretical-historical focus.

The final segment of the book, part 3, contributes two case studies on three films that conduct discourses on the stereotypes of film—as examined up to this point from the perspective of film theory. The first analysis comprises two films from the 1970s by Robert Altman that critically address the stereotypes of the Western genre. The second deals with the acting technique of Jennifer Jason Leigh in the Coen brothers’ film The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), which reflexively presents and celebrates stereotypes in a “postmodern” sense by adhering to a strategy of reflexive transfiguration.

Illustrating two basic variations of the reflexive approach to stereotypes, these two film analyses conclude the survey and, by way of pars pro toto, also represent its guiding principle. Although the historical and theoretical analysis of this final section was developed by following multiple stages or paradigms of the theoretical “approach” to the stereotype, it too, like the book as a whole, is not obsessed with completeness or the ambition to create a closed system, an endeavor that would be questionable from the start. More important than any pretensions to exhaustiveness or definitiveness are the inspiration and threads that this book may provide for further reflection and additional analysis.

EDITORIAL NOTE

This book was prepared in the second half of the 1990s and written just before and after the year 2000, although its inception and early research dates further back. The study was presented in 2002 as the author’s second thesis (Habilitation)at the University of Konstanz and was published in slightly revised form in 2006 by Akademie Verlag Berlin. The translation largely corresponds to the German edition (at the time of going to press in 2005). With respect to the American readership, some text passages have undergone minor modification, and additional selective reference is made to more recent secondary literature in English, without any claim, however, to being exhaustive.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for generously funding the study with a research grant. Special thanks go to Wolfgang Beilenhoff, Heinz B. Heller, Knut Hickethier, Tom Gunning, Thomas Koebner, Thomas Y. Levin, Karl Prümm, Irmela Schneider, Hans Jürgen Wulff, and Peter Wuss, who graciously supported my work during the phases of conception, research, and writing with research facilities and provided me with numerous opportunities for developing and testing some of the book’s core ideas in classes and in exchange with students, namely as visiting professor or research fellow at the Universities of Freie Universität Berlin, Chicago, Klagenfurt, Marburg, Potsdam, and Princeton.

Without the many talks and discussions with friends and colleagues, their suggestions, encouragement, and assistance, the long haul of the project would have been hardly manageable. On this count, I am especially indebted to Margrit Tröhler, Anne Paech, and my fellow editorial board members of Montage AV, above all Britta Hartmann and Frank Kessler.

Special thanks go to Eberhard Lämmert and Joachim Paech for their continuous support during the second-thesis procedure at the University of Konstanz.

Peter Heyl and Sabine Cofalla of Akademie Verlag Berlin expertly saw the manuscript through to its German publication. In 2008, the book won the Geisteswissenschaften International Award, a prize for the promotion of translating German works in the humanities, donated by the Thyssen Foundation, the Börsenverein des deutschen Buchhandels, and the German Foreign Office.

I am indebted to Christine Noll Brinckmann for her suggestion of the series of images on the cover of this book, which show the visual stereotype of women behind the window.

I would further like to thank Henry M. Taylor for our joint discussions concerning appropriate English professional terminology and for his useful suggestions of specialist terms while intently accompanying the translation process; Mona Salari for her bibliographical research; and, above all, Laura Schleussner for her dedication and precise translation work, her intensive search for hard-to-find sources of English quotations, and her abiding patience with the author’s requests.