CHAPTER EIGHT

Believe Everything, Trust Nothing

When the telephone was still a novelty, it was physically wired into the home and perhaps placed in a nook built into the wall. Getting a second line was considered a status symbol. Similarly, public phone booths were built for privacy. Even banks of pay phones in hotel lobbies were equipped with sound baffles between them to give the illusion of privacy.

With mobile phones, that sense of privacy has fallen away entirely. It is common to walk down the street and hear people loudly sharing some personal drama or—worse—reciting their credit card number within earshot of all who pass by. In the midst of this culture of openness and sharing, we need to think carefully about the information we’re volunteering to the world.

Sometimes the world is listening. I’m just saying.

Suppose you like to work at the café around the corner from your home, as I sometimes do. It has free Wi-Fi. That should be okay, right? Hate to break it to you, but no. Public Wi-Fi wasn’t created with online banking or e-commerce in mind. It is merely convenient, and it’s also incredibly insecure. Not all that insecurity is technical. Some of it begins—and, I hope, ends—with you.1

How can you tell if you are on public Wi-Fi? For one thing, you won’t be asked to input a password to connect to the wireless access point. To demonstrate how visible you are on public Wi-Fi, researchers from the antivirus company F-Secure built their own access point, or hotspot. They conducted their experiment in two different locations in downtown London—a café and a public space. The results were eye-opening.

In the first experiment, the researchers set up in a café in a busy part of London. When patrons considered the choices of available networks, the F-Secure hotspot came up as both strong and free. The researchers also included a banner that appeared on the user’s browser stating the terms and conditions. Perhaps you’ve seen a banner like this at your local coffee shop stipulating what you can and cannot do while using their service. In this experiment, however, terms for use of this free Wi-Fi required the surrender of the user’s firstborn child or beloved pet. Six people consented to those terms and conditions.2 To be fair, most people don’t take the time to read the fine print—they just want whatever is on the other end. Still, you should at least skim the terms and conditions. In this case, F-Secure said later that neither it nor its lawyers wanted anything to do with children or pets.

The real issue is what can be seen by third parties while you’re on public Wi-Fi. When you’re at home, your wireless connection should be encrypted with WPA2 (see here). That means if anyone is snooping, he or she can’t see what you’re doing online. But when you’re using open, public Wi-Fi at a coffee shop or airport, that destination traffic is laid bare.

Again you might ask, what’s the problem with all this? Well, first of all, you don’t know who’s on the other end of the connection. In this case the F-Secure research team ethically destroyed the data they collected, but criminals probably would not. They’d sell your e-mail address to companies that send you spam, either to get you to buy something or to infect your PC with malware. And they might even use the details in your unencrypted e-mails to craft spear-phishing attacks.

In the second experiment, the team set the hotspot on a balcony in close proximity to the Houses of Parliament, the headquarters of the Labour and Conservative parties, and the National Crime Agency. Within thirty minutes a total of 250 people connected to the experimental free hotspot. Most of these were automatic connections made by whatever device was being used. In other words, the users didn’t consciously choose the network: the device did that for them.

A couple of issues here. Let’s first look at how and why your mobile devices automatically join a Wi-Fi network.

Your traditional PC and all your mobile devices remember your last few Wi-Fi connections, both public and private. This is good because it saves you the trouble of continually reidentifying a frequently used Wi-Fi access point—such as your home or office. This is also bad because if you walk into a brand-new café, a place you’ve never been before, you might suddenly find that you have wireless connectivity there. Why is that bad? Because you might be connected to something other than the café’s wireless network.

Chances are your mobile device detected an access point that matches a profile already on your most recent connection list. You may sense something amiss about the convenience of automatically connecting to Wi-Fi in a place you’ve never been before, but you may also be in the middle of a first-person shooter game and don’t want to think much beyond that.

How does automatic Wi-Fi connection work? As I explained in the last chapter, maybe you have Comcast Internet service at home, and if you do you might also have a free, nonencrypted public SSID called Xfinity as part of your service plan. Your Wi-Fi-enabled device may have connected to it once in the past.3 But how do you know that the guy with a laptop at the corner table isn’t broadcasting a spoofed wireless access point called Xfinity?

Let’s say you are connected to that shady guy in the corner and not to the café’s wireless network. First, you will still be able to surf the Net. So you can keep on playing your game. However, every packet of unencrypted data you send and receive over the Internet will be visible to this shady character through his spoofed laptop wireless access point.

If he’s taken the trouble to set up a fake wireless access point, then he’s probably capturing those packets with a free application such as Wireshark. I use this app in my work as a pen tester. It allows me to see the network activity that’s going on around me. I can see the IP addresses of sites people are connecting to and how long they are visiting those sites. If the connection is not encrypted, it is legal to intercept the traffic because it is generally available to the public. For example, as an IT admin, I would want to know the activity on my network.

Maybe the shady guy in the corner is just sniffing, seeing where you go and not influencing the traffic. Or maybe he is actively influencing your Internet traffic. This would serve multiple purposes.

Maybe he’s redirecting your connection to a proxy that implants a javascript keylogger in your browser so when you visit Amazon your keystrokes will be captured as you interact with the site. Maybe he gets paid to harvest your credentials—your username and password. Remember that your credit card may be associated with Amazon and other retailers.

When delivering my keynote, I give a demonstration that shows how I can intercept a victim’s username and password when accessing sites once he or she is connected to my spoofed access point. Because I’m sitting in the middle of the interaction between the victim and the website, I can inject JavaScript and cause fake Adobe updates to pop up on his or her screen, which, if installed will infect the victim’s computer with malware. The purpose is usually to trick you into installing the fake update to gain control of your computer.

When the guy at the corner table is influencing the Internet traffic, that’s called a man-in-the-middle attack. The attacker is proxying your packets through to the real site, but intercepting or injecting data along the way.

Knowing that you could unintentionally connect to a shady Wi-Fi access point, how can you prevent it? On a laptop the device will go through the process of searching for a preferred wireless network and then connect to it. But some laptops and mobile devices automatically choose what network to join. This was designed to make the process of taking your mobile device from one location to another as painless as possible. But as I mentioned, there are downsides to this convenience.

According to Apple, its various products will automatically connect to networks in this order of preference:

1. the private network the device most recently joined,

2. another private network, and

3. a hotspot network.

Laptops, fortunately, provide the means to delete obsolete Wi-Fi connections—for example, that hotel Wi-Fi you connected to last summer on a business trip. In a Windows laptop, you can uncheck the “Connect Automatically” field next to the network name before you connect. Or head to Control Panel>Network and Sharing Center and click on the network name. Click on “Wireless Properties,” then uncheck “Connect automatically when this network is in range.” On a Mac, head to System Preferences, go to Network, highlight Wi-Fi on the left-hand panel, and click “Advanced.” Then uncheck “Remember networks this computer has joined.” You can also individually remove networks by selecting the name and pressing the minus button underneath it.

Android and iOS devices also have instructions for deleting previously used Wi-Fi connections. On an iPhone or iPod, go into your settings, select “Wi-Fi,” click the “i” icon next to the network name, and choose “Forget This Network.” On an Android phone, you can go into your settings, choose “Wi-Fi,” long-press the network name, and select “Forget Network.”

Seriously, if you really have something sensitive to do away from your house, then I recommend using the cellular connection on your mobile device instead of using the wireless network at the airport or coffee shop. You can also tether to your personal mobile device using USB, Bluetooth, or Wi-Fi. If you use Wi-Fi, then make sure you configure WPA2 security as mentioned earlier. The other option is to purchase a portable hotspot to use when traveling. Note, too, this won’t make you invisible, but is a better alternative than using public Wi-Fi. But if you need to protect your privacy from the mobile operator—say, to download a sensitive spreadsheet—then I suggest you use HTTPS Everywhere or a Secure File Transfer Protocol (SFTP). SFTP is supported using the Transmit app on Mac and the Tunnelier app on Windows.

A virtual private network (VPN) is a secure “tunnel” that extends a private network (from your home, office, or a VPN service provider) to your device on a public network. You can search Google for VPN providers and purchase service for approximately $60 a year. The network you’ll find at the local coffee shop or the airport or in other public places is not to be trusted—it’s public. But by using a VPN you can tunnel through the public network back to a private and secure network. Everything you do within the VPN is protected by encryption, as all your Internet traffic is now secured over the public network. That’s why it’s important to use a VPN provider you can trust—it can see your Internet traffic. When you use a VPN at the coffee shop, the sketchy guy in the corner can only see that you have connected to a VPN server and nothing else—your activities and the sites you visit are all completely hidden behind tough-to-crack encryption.

However, you will still touch the Internet with an IP address that is traceable directly to you, in this case the IP address from your home or office. So you’re still not invisible, even using a VPN. Don’t forget—your VPN provider knows your originating IP address. Later we’ll discuss how to make this connection invisible (see here).

Many companies provide VPNs for their employees, allowing them to connect from a public network (i.e., the Internet) to a private internal corporate network. But what about the rest of us?

There are many commercial VPNs available. But how do you know whether to trust them? The underlying VPN technology, IPsec (Internet protocol security), automatically includes PFS (perfect forward secrecy; see here), but not all services—even corporate ones—actually bother to configure it. OpenVPN, an open-source project, includes PFS, so you might infer that when a product says it uses OpenVPN it also uses PFS, but this is not always the case. The product might not have OpenVPN configured properly. Make sure the service specifically includes PFS.

One disadvantage is that VPNs are more expensive than proxies.4 And, since commercial VPNs are shared, they can also be slow, or in some cases you simply can’t get an available VPN for your personal use and you will have wait until one becomes available. Another annoyance is that in some cases Google will pop up a CAPTCHA request (which asks you to type in the characters you see on the screen) before you can use its search engine because it wants to make sure you are a human and not a bot. Finally, if your particular VPN vendor keeps logs, read the privacy policy to make sure that the service doesn’t retain your traffic or connection logs—even encrypted—and that it doesn’t make the data easy to share with law enforcement. You can figure this out in the terms of service and privacy policy. If they can report activities to law enforcement, then they do log VPN connections.

Airline passengers who use an in-air Internet service such as GoGo run the same risk as they do going online while sitting in a Starbucks or airport lounge, and VPNs aren’t always great solutions. Because they want to prevent Skype or other voice-call applications, GoGo and other in-air services throttle UDP packets—which will make most VPN services very slow as UDP is the protocol most use by default. However, choosing a VPN service that uses the TCP protocol instead of UDP, such as TorGuard or ExpressVPN, can greatly improve performance. Both of these VPN services allow the user to set either TCP or UDP as their preferred protocol.

Another consideration with a VPN is its privacy policy. Whether you use a commercial VPN or a corporate-provided VPN, your traffic travels over its network, which is why it’s important to use https so the VPN provider can’t see the contents of your communications.5

If you work in an office, chances are your company provides a VPN so that you can work remotely. Within an app on your traditional PC, you type in your username and password (something you know). The app also contains an identifying certificate placed there by your IT department (something you already have), or it may send you a text on your company-issued phone (also something you have). The app may employ all three techniques in what’s known as multifactor authentication.

Now you can sit in a Starbucks or an airport lounge and conduct business as though you were using a private Internet service. However, you should not conduct personal business, such as remote banking, unless the actual session is encrypted using the HTTPS Everywhere extension.

The only way to trust a VPN provider is to be anonymous from the start. If you really want to be completely anonymous, never use an Internet connection that could be linked to you (i.e., one originating from your home, office, friends’ homes, a hotel room reserved in your name, or anything else connected to you). I was caught when the FBI traced a cell-phone signal to my hideout in Raleigh, North Carolina, back in the 1990s. So never access personal information using a burner device in the same location if you’re attempting to avoid governmental authorities. Anything you do on the burner device has to be completely separate in order to remain invisible. Meaning that no metadata from the device can be linked to your real identity.

You can also install a VPN on your mobile device. Apple provides instructions for doing so,6 and you can find instructions for Android devices as well.7

If you have been following my advice in the book so far, you’ll probably fare much better than the average Joe. Most of your Internet usage will probably be safe from eavesdropping or manipulation by an attacker.

So will your social media. Facebook uses https for all its sessions.

Checking your e-mail? Google has also switched over to https only. Most Web mail services have followed, as have most major instant messaging services. Indeed, most major sites—Amazon, eBay, Dropbox—all now use https.

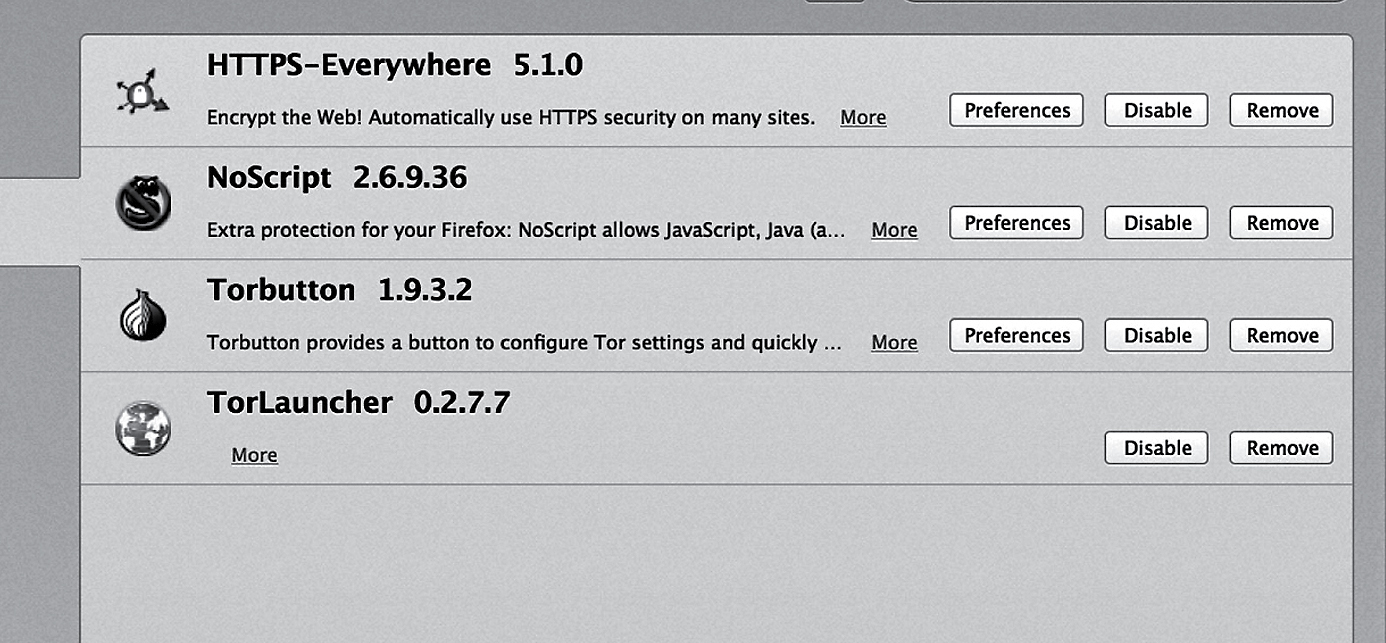

To be invisible, it’s always best to layer your privacy. Your risk of having your traffic viewed by others in a public network declines with each additional layer of security you employ. For example, from a public Wi-Fi network, access your paid VPN service, then access Tor with the HTTPS Everywhere extension installed by default in the Firefox browser.

Then whatever you do online will be encrypted and hard to trace.

Say you just want to check the weather and not do anything financial or personal, and you are using your own personal laptop outside your home network—that should be secure, right? Once again, not really. There are a few precautions you still need to take.

First, turn off Wi-Fi. Seriously. Many people leave Wi-Fi on their laptops turned on even when they don’t need it. According to documents released by Edward Snowden, the Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) can identify travelers passing through Canadian airports just by capturing their MAC addresses. These are readable by any computer that is searching for any probe request sent from wireless devices. Even if you don’t connect, the MAC address can be captured. So if you don’t need it, turn off your Wi-Fi.8 As we’ve seen, convenience often works against privacy and safety.

So far we’ve skirted around an important issue—your MAC address. This is unique to whatever device you are using. And it is not permanent; you can change it.

Let me give you an example.

In the second chapter, I told you about encrypting your e-mail using PGP (Pretty Good Privacy; see here). But what if you don’t want to go through the hassle, or what if the recipient doesn’t have a public PGP key for you to use? There is another clandestine way to exchange messages via e-mail: use the drafts folder on a shared e-mail account.

This is how former CIA director General David Petraeus exchanged information with his mistress, Paula Broadwell—his biographer. The scandal unfolded after Petraeus ended the relationship and noticed that someone had been sending threatening e-mails to a friend of his. When the FBI investigated, they found not only that the threats had come from Broadwell but that she had also been leaving romantic messages for Petraeus.9

What’s interesting is that the messages between Broadwell and Petraeus were not transmitted but rather left in the drafts folder of the “anonymous” e-mail account. In this scenario the e-mail does not pass through other servers in an attempt to reach the recipient. There are fewer opportunities for interceptions. And if someone does get access to the account later on, there will be no evidence if you delete the e-mails and empty the trash beforehand.

Broadwell also logged in to her “anonymous” e-mail account using a dedicated computer. She did not contact the e-mail site from her home IP address. That would have been too obvious. Instead she went to various hotels to conduct her communications.

Although Broadwell had taken considerable pains to hide, she still was not invisible. According to the New York Times, “because the sender’s account had been registered anonymously, investigators had to use forensic techniques—including a check of what other e-mail accounts had been accessed from the same computer address—to identify who was writing the e-mails.”10

E-mail providers such as Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft retain log-in records for more than a year, and these reveal the particular IP addresses a consumer has logged in from. For example, if you used a public Wi-Fi at Starbucks, the IP address would reveal the store’s physical location. The United States currently permits law enforcement agencies to obtain these log-in records from the e-mail providers with a mere subpoena—no judge required.

That means the investigators had the physical location of each IP address that contacted that particular e-mail account and could then match Broadwell’s device’s MAC address on the router’s connection log at those locations.11

With the full authority of the FBI behind them (this was a big deal, because Petraeus was the CIA director at the time), agents were able to search all the router log files for each hotel and see when Broadwell’s MAC address showed up in hotel log files. Moreover, they were able to show that on the dates in question Broadwell was a registered guest. The investigators did note that while she logged in to these e-mail accounts, she never actually sent an e-mail.

When you connect to a wireless network, the MAC address on your computer is automatically recorded by the wireless networking equipment. Your MAC address is similar to a serial number assigned to your network card. To be invisible, prior to connecting to any wireless network you need to change your MAC address to one not associated with you.

To stay invisible, the MAC address should be changed each time you connect to the wireless network so your Internet sessions cannot easily be correlated to you. It’s also important not to access any of your personal online accounts during this process, as it can compromise your anonymity.

Instructions for changing your MAC address vary with each operating system—i.e., Windows, Mac OS, Linux, even Android and iOS.12 Each time you connect to a public (or private) network, you might want to remember to change your MAC address. After a reboot, the original MAC address returns.

Let’s say you don’t own a laptop and have no choice but to use a public computer terminal, be it in a café, a library, or even a business center in a high-end hotel. What can you do to protect yourself?

When I go camping I observe the “leave no trace” rule—that is, the campsite should look just as it did when I first arrived. The same is true with public PC terminals. After you leave, no one should know you were there.

This is especially true at trade shows. I was at the annual Consumer Electronics Show one year and saw a bank of public PCs set out so that attendees could check their e-mail while walking the convention floor. I even saw this at the annual security-conscious RSA conference, in San Francisco. Having a row of generic terminals out in public is a bad idea for a number of reasons.

One, these are leased computers, reused from event to event. They may be cleaned, the OS reinstalled, but then again they might not be.

Two, they tend to run admin rights, which means that the conference attendee can install any software he or she wants to. This includes malware such as keyloggers, which can store your username and password information. In the security business, we speak of the principle of “least privilege,” which means that a machine grants a user only the minimum privileges he or she needs to get the job done. Logging in to a public terminal with system admin privileges, which is the default position on some public terminals, violates the principle of least privilege and only increases the risk that you are using a device previously infected with malware. The only solution is to somehow be certain that you are using a guest account, with limited privileges, which most people won’t know how to do.

In general I recommend never trusting a public PC terminal. Assume the person who last used it installed malware—either consciously or unconsciously. If you log in to Gmail on a public terminal, and there’s a keylogger on that public terminal, some remote third party now has your username and password. If you log in to your bank—forget it. Remember, you should enable 2FA on every site you access so an attacker armed with your username and password cannot impersonate you. Two-factor authentication will greatly mitigate the chances of your account being hacked if someone does gain knowledge of your username and password.

The number of people who use public kiosks at computer-based conferences such as CES and RSA amazes me. Bottom line, if you’re at a trade show, use your cellular-enabled phone or tablet, your personal hotspot (see here), or wait until you get back to your room.

If you have to use the Internet away from your home or office, use your smartphone. If you absolutely have to use a public terminal, then do not by any means sign in to any personal account, even Web mail. If you’re looking for a restaurant, for example, access only those websites that do not require authentication, such as Yelp. If you use a public terminal on a semiregular basis, then set up an e-mail account to use only on public terminals, and only forward e-mail from your legitimate accounts to this “throwaway” address when you are on the road. Stop forwarding once you return home. This minimizes the information that is findable under that e-mail address.

Next, make sure the sites you access from the public terminal have https in the URL. If you don’t see https (or if you do see it but suspect that someone has put it there to give you a false sense of security), then perhaps you should reconsider accessing sensitive information from this public terminal.

Let’s say you get a legitimate https URL. If you’re on a log-in page, look for a box that says “Keep me logged in.” Uncheck that. The reason is clear: this is not your personal PC. It is shared by others. By keeping yourself logged in, you are creating a cookie on that machine. You don’t want the next person at the terminal to see your e-mail or be able to send e-mail from your address, do you?

As noted, don’t log in to financial or medical sites from a public terminal. If you do log in to a site (whether Gmail or otherwise), make sure you log off when you are done and perhaps consider changing your password from your own computer or mobile device afterward just to be safe. You may not always log off from your accounts at home, but you must always do this when using someone else’s computer.

After you’ve sent your e-mail (or looked at whatever you wanted to look at) and logged off, then try to erase the browser history so the next person can’t see where you’ve been. Also delete any cookies if you can. And make sure you didn’t download personal files to the computer. If you do, then try to delete the file or files from the desktop or downloads folder when you’re finished.

Unfortunately, though, just deleting the file isn’t enough. Next you will need to empty the trash. That still doesn’t fully remove the deleted stuff from the computer—I can retrieve the file after you leave if I want to. Thankfully, most people don’t have the ability to do that, and usually deleting and emptying the trash will suffice.

All these steps are necessary to be invisible on a public terminal.