Talking about the political ‘Uses of Photography,’ John Berger says ‘most photographs . . . are about suffering, and most of that suffering is man-made’.1 The reason the point is worth making, he thinks, is because a lot of photography conceals it, his exemplary instance being Edward Steichen’s famous Family of Man show (1955), which – treating ‘the existing class-divided world as if it were a family’ – produced a ‘sentimental and complacent’ vision of that world. It’s not that Steichen was wrong to want to think of ‘man’ as belonging to one family. The sentimentality was in depicting the world as if we already did and hence in obscuring both the political causes of suffering and the cure. By contrast, he offers us Susan Sontag’s account of the ‘negative epiphany’ she experienced on first seeing photographs of Bergen-Belsen and Dachau. Nothing she had ever seen, Sontag writes, ‘cut me as sharply, deeply, instantaneously’. His idea is that in order for photography to have any political value, it must – as these photographs did for Sontag – depict the truth of suffering; her idea is that when it does it will cut deep, so deep it’s almost a cause of suffering itself, leading the beholder to feel something of what the subject feels.

Indeed, the political potential not only of photography but of art more generally depends, Sontag thinks, on its ‘responsiveness to suffering’, and here the danger of sentimentality (especially for the art of photography) is even more pronounced.2 For if the identificatory effect on the viewer – the sympathy produced by feeling something of what the victim feels – is desirable, it is also dangerous, since our sense that we in some sense share the victim’s pain may function to repress the recognition that we may in some sense also be responsible for that pain; that ‘our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering and may – in ways we prefer not to imagine – be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others’.3 Furthermore, because photographs ‘tend to transform . . . their subject,’ photography can make something ‘beautiful’ ‘as an image’ when ‘in real life’ ‘it is not’.4 Thus it ‘seems exploitative to look at harrowing photographs of other people’s pain in an art gallery’, partly because the ‘social situation’ of the gallery distracts from the ‘strong emotion’ the work might produce and, perhaps more importantly, because the emotion may be a response to the work as a work of art.5 In other words, if art photography holds out the promise of producing in the viewer a response to the actual suffering a photograph can depict, it also runs the risk that what the viewer will respond to will be the photograph itself and not the photograph’s subject; the art instead of the suffering.

On this model, a model that essentially takes the photographs of the camps as its model, the challenge political photography faces is how to insist on suffering without either aestheticizing or sentimentalizing it. But is this model the right one? I want to suggest that it isn’t and, looking at one book by the young American photographer Daniel Shea, I want to argue instead that the point of political photography today cannot be to try to achieve either the right relation with the suffering victim (honoring his dignity, etc.) or the right effect on the compassionate beholder (cutting her just enough to move her in the right way or to the right degree). In fact, I want to say that this interest in the ethical problem of the relations between the photographer and the viewer and the subject of the photograph is itself a kind of sentimentality, and its politics are those of a left neoliberalism: of human rights, diversity, NGOs. By contrast, Shea’s commitment is to the aesthetic instead of the ethical, and his understanding of what it means to make art out of photography requires a certain indifference to both his subjects and his audience. It’s that aesthetic of indifference that makes possible, I will argue, a certain politics of indifference – a politics that instead, say, of just seeking justice for those who have been treated unfairly by the labour market, seeks to alter the conditions under which that market functions; that instead of focusing on the victims of abuses in what Berger calls ‘a class-divided society’, focuses on the abuse of class division itself; a politics that, in other words, is not left neoliberal but left.

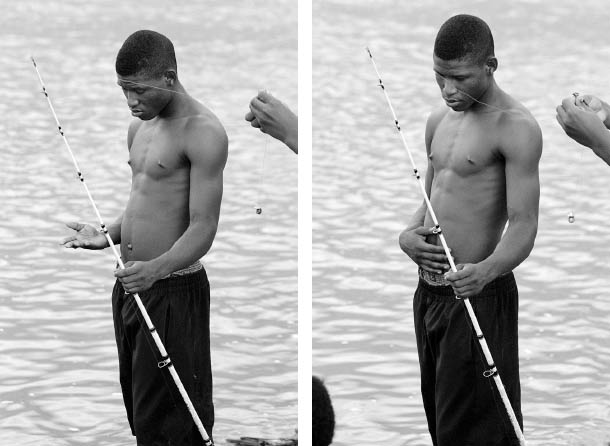

The photos in Shea’s Blisner, IL were taken between 2011 and 2014 in southern Illinois (IL is the postal abbreviation for Illinois). Because they’re photographs (not drawings or descriptions), what they show us is what was there – in front of Shea’s camera – and what it looked like at the moment he made a picture of it. The pictures, in other words, are linked to the thing they are of and to the moment in which they were made in ways that other modes of representation are not. If Blisner, IL were a collection of stories for example (like one of its obvious analogies, Sherwood Anderson’s short story cycle Winesburg, Ohio), the young man fishing, the train tracks, the statues would never have had to be present in front of the author’s pen or even to have existed at all.

And it could be set in the early twenty-first century without having been written in the early twenty-first century. Which is just to say that, as a book of photographs, Blisner makes distinctive ontological and historical claims: that those people and those train tracks were really there, and that the photographer was there too.

But Blisner wasn’t there. The pictures are of real things but the town is not a real place. So one of the things the book is interested in is how a fiction can be produced out of non-fictional elements. And if Daniel Shea’s presence when the photographs were made makes an irreducible historical claim – this is what this wall looked like then, in 2012 – it’s also true that the punctuality of that moment is as misleading as it is illuminating. Blisner, IL is as much the picture of a process as of a moment. Just as de-industrialization was made possible by industrialization, the photo of an aging wall refers also to a time when it was in better shape. The exhortation painted on this one – why not now? – was painted on it some time ago; ‘now,’ in this picture, means also ‘then’. So one way to think about the multiplicity of times deployed in Blisner is that they construct a narrative and, in particular, a narrative of decline, of things that were made a long time ago and that are now crumbling. Sticking with de-industrialization, manufacturing jobs in the US hit their peak in the mid-1970s and have today hit a new low; in the same period, the real wealth of the bottom 60 per cent of the population has declined. More particularly, Illinois has lost 330,500 (5.6 per cent) manufacturing jobs since 1998.6

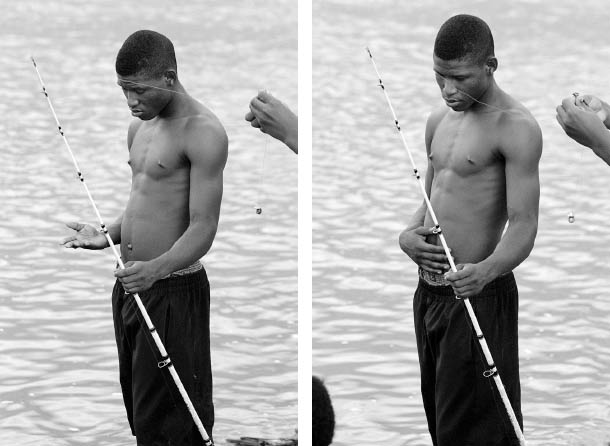

But although there’s an important sense in which that’s the story Blisner tells, there’s an even more important sense in which it isn’t – in which the book is not about decline and isn’t exactly a narrative either. Most obviously, Blisner, IL’s opening photographs are not of the declining fictional town Blisner, IL, but of another Blisner book (Blisner, Ill, published in 2012) to which this one is a sequel. The object these photos depict was made just a few years ago, and it belongs to the burgeoning (albeit cottage) industry of the photo book. And these new photos were made in a studio in Long Island City, which (unlike the places in Illinois where the others were taken) is in the midst of what the Commercial Observer in New York describes as a ‘dramatic makeover from an industrial wasteland to a residential destination’,7 just the kind of transformation often precipitated by the arrival of artists like Shea. So one thing the juxtaposition of Blisner (the book) and Blisner (the town) asks us to think about is the simultaneity of economic activity and economic stagnation – two aspects of the same thing, connected less by a narrative than by a logic. Or if we want to hang on to narrative, we could say that their juxtaposition begins to inscribe both the history of the town and the history of the book in the history of something else – the history of societies organized by the relation between capital and labour.

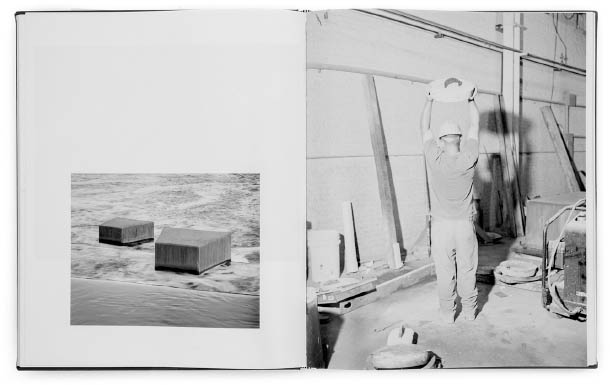

And also, the history of art. For if the newly neoliberal 1970s were a crucial economic moment in American capitalism, they were equally crucial in the history of photography, or at least in the history of photography as an art form. Writers like Jean-François Chevrier and Michael Fried have identified the beginning of what Fried calls ‘a new regime’ of art photography with the emergence in this period of ‘a tendency toward a considerably larger image size than had previously been thought appropriate to art photography’ and hence ‘an intention that the photographs in question would be framed and hung on a wall’, to be looked at, Fried adds, ‘like paintings’.8 Today anybody who’s interested in photography is familiar with the achievements made possible by this development. But today – as exemplified in Shea’s commitment to the photography book – we are also seeing something different. After thirty years of being asked by ambitious art to look at the picture on the wall, we are increasingly being asked to hold it in our hand; not to walk through the gallery but to turn the page. And if, in one sense, this represents a return to what for many years was arguably the dominant, even default, tradition in photography, it also represents something new. Before the new regime, no one making photography books was expressing a preference for the small image on the page over the large image on the wall; the large image wasn’t even an option. But today, for someone like Shea, the photo book is not what it once was – a norm – but what large format photographs have made it – a choice. And it’s not only a way of showing your pictures; it’s a particular kind of aesthetic object.

This way of putting the point might make some writers on photography a little nervous. In volume three of their invaluable The Photobook: A History, for example, Martin Parr and Gerry Badger lament the degree to which photography has been ‘colonized by the art museum’ and they deplore the ‘tendency’ of critics to ‘discuss photographs in aesthetic terms’ and of photographers to forsake the ‘documentary’.9 From their standpoint, the idea that the photobook has been ‘reinvigorated’ in part as a refusal of the museum wall might look attractive.10 But the idea that the terms of this refusal are themselves aesthetic would not. In fact, the opening pages of Blisner (the photographs of the first book) might count for them as an exemplary instance of a photography they criticize for being ‘as self-referential and as solipsistic as a lot of the work currently afflicting contemporary art’.

Their worry is that a commitment to the specifically aesthetic is at best distracting from and at worst incompatible with a real politics. From this standpoint, the photobook that begins with a picture of another photobook – more generally, a work of art concerned above all with itself as a work of art – might seem to abandon the distinctive purchase on the world outside the book that seems to give the photograph whatever political power it has.

But what I’m saying here is just the opposite.11 The inscription on Blisner’s binding reads ‘An Index of Work As Labor As Work’. The ‘index’ registers photography’s purchase on the world (the photograph’s distinctive causal link to the conditions under which it was produced: no photo of two young men fishing without two young men actually fishing). The redescription of that work as labor points toward a particular understanding of those conditions and of what the photographer does that makes sense of them in relation to capital, and thus makes possible the production of something different – work as, or the work of, art. And it’s this claim to be a work of art that, far from refusing the social and political issues raised by documentary, makes it possible to produce them at a level the documentary in itself cannot quite attain, and with a political vision that, in the current moment, one might even characterize as revolutionary in a way that (for now) no politics can quite be.

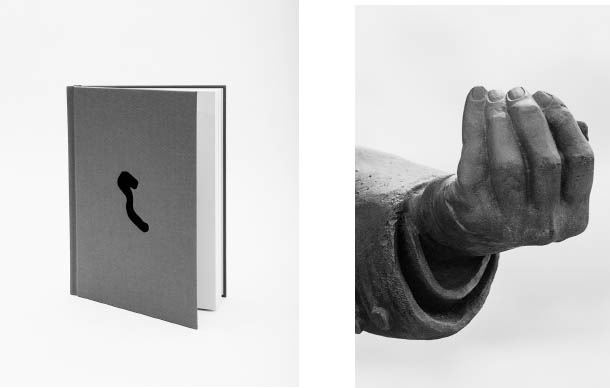

I’ve already begun to describe Blisner’s claim to the aesthetic by noting that its opening pages thematize the fact that it is a book, with a relation to another book. But the distinctive marks of what it means for it to be a book are everywhere, for example in the difference between the two opposite page photographs of the old movie theatre which you see at the same time, and the two pictures of streetlights which (since you have to turn the page) you can only see separately. More generally, there are many pairings, often but not always of different pictures of the same thing, and the fact of the pairs (more or less inevitable, given the structure of any book) is marked by the further fact that so many photos are not paired, that they appear instead opposite a blank page and that the negative space of the blank page – indeed the negative space of the pages where there are photos – is deployed as something you are meant to see rather than as the background of something you’re meant to see. Thus for example with respect to the bridge that bleeds from the left page onto the right (itself a description that depends on the distinctive structure of the book), the white space between the edge of the right page and the edge of the photograph structures the photograph differently from the ones that occupy two full pages, if only because it produces that sense in the photograph itself of motion from left to right.

Why does this matter? It matters because, instead of presenting itself as a collection of pictures a viewer might look at in the same way you might walk around a gallery or look around a website, Blisner presents itself as having its own order, its own principle of organization. Interestingly, distinguishing between the experience of the book and the experience of the gallery, Sontag (in 2003) was already speculating on the advantages of the book in the hand over the picture on the wall. Her thought was that because ‘one can look privately’ and ‘linger over the pictures,’ the ‘weight and seriousness’ of photographs of suffering ‘survive better in a book’ than they do in the ‘social situation’ of a gallery or museum visit. Her interest in the book, in other words, was in its relative success in producing and maintaining appropriately ‘strong emotions’. But the effect on the reader is not at all what’s at stake with Blisner. Here the reader is free to linger or not linger and, like Sontag’s gallery-goer, to look at the pictures in any order we want. But the order they’re actually in has nothing to do with us, and it’s this assertion of an order that is independent of the reader – that belongs to the book instead of to the reader – that matters. More generally, the insistence that every part of the book is related to every other part of the book is what serves to establish its autonomy – the relatedness of everything inside it, the irrelevance of everything outside it. And it’s this autonomy – both the demand that the work be experienced as a whole and the concomitant indifference to how its individual readers experience it (its refusal, more generally, of a certain appeal to its readers) – that not only constitutes Blisner’s politics but defines them in left (rather than in liberal) terms.

That’s the point of making photographers’ studios in gentrifying Long Island City and coal mining towns in de-industrializing southern Illinois elements in a single entity. It’s what the communist and literary theorist Georg Lukács used to call the necessity of ‘picturing capitalist development as a whole’.12 And it’s even more vividly the point of establishing the irrelevance of the viewer’s relation to this whole. Depending on where we are (in southern Illinois or in Queens) and who we are (people who make and buy books like Blisner or people pictured in them), we will have very different experiences of our moment in ‘capitalist development’, and we will naturally feel very differently about them. But if those feelings are inevitable and even sometimes attractive, they are also in the end of secondary interest. In a society organized by class, everybody belongs to one, and if you want to change that society, it doesn’t matter which one you belong to. To put the point in the terms usefully introduced by Sontag, this juxtaposition of art flourishing in Long Island City with industry dying in southern Illinois does indeed suggest the way in which ‘our privileges’ may be ‘linked to their suffering’, in exactly the way that ‘the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others’. But where for Sontag the goal is for the beholder to feel both sympathy and something like guilt, for Shea the question of how we feel (sympathetic or complicit or both) is irrelevant.

More abstractly, the relation between capital and labor is not structured by the way capitalists feel about workers or workers about capitalists, or by any appeal one could make to the other. More concretely, as in this photo of a painting of a child’s hands reaching to the grown-up’s, the pathos (the plea for compassion) is assigned to the work of art the photo shows (not the one it is) and is offset by the power of the paired photographs that precede it – of the young man with the fishing rod, self-contained, whose hands make no appeal, and of the leaf-like fingers (almost more like fingers than the painted fingers) of the inverted (negative) image that, after a page of negative space, follows it. So what’s involved in picturing the whole is not exactly eliminating our feelings about these people, but transforming them into feelings about the work of art that structures the relation between them.

In other words, if one way to understand photography as political art is to see it as soliciting our identification with, compassion for, and perhaps activism on behalf of those left behind in places like Blisner, that’s not Blisner’s way. It’s not Blisner’s aesthetic and it’s not Blisner’s politics. It’s not even Blisner’s idea of what politics is.

We can begin to see this by thinking about the young black man fishing in Blisner in relation to the white artist and the statistically white viewer of the picture. What I mean by calling the viewer statistically white is that, just as blacks are over-represented among the poor in the U.S., whites are over-represented among the upper-middle class, the class that cares most about photography as art. So one plausible way to look at this young man is as a victim of the racism that has created those disproportions and a plausible way to understand his presence in this book is as an anti-racist appeal to its readers. But, aesthetically, I’ve already begun to suggest some of the reasons for thinking he’s not there to solicit the complex feelings about black people (guilt tinged with admiration, aversion combined with attraction, etc.) that white (especially upper-class white) Americans have a virtuoso command of. And, politically, the very things that produce that virtuosity – the effects of racism, the disparities between whites and blacks in wealth, in health, in education, etc. – are as irrelevant to Blisner’s politics as compassion is to its aesthetic. Indeed, the politics of what Adolph Reed and Merlin Chowkwanyun call disparitarianism and the prominence of anti-racism are more the problem than the solution, since they function primarily to articulate the ruling-class view that discrimination and not exploitation is the cause of American inequality. And in the U.S., the ideological success of this argument makes it a weapon against even the slightest move toward a working-class politics (e.g. the Sanders campaign) by insisting, in Hillary Clinton’s words, that ‘if we broke up the big banks tomorrow’ that wouldn’t ‘end racism’ or ‘sexism’.13

Here neoliberal ethics (holding neoliberalism to its own ideals) are deployed instead of, and against, an anti-neoliberal politics. Instead of the structural change that would, for example, take health care and higher education out of the market, it’s structural racism we’re urged to worry about, because that deprives many people of a fair chance to be successful in the market. It’s for this reason that the politics of anti-discrimination today is in no sense a left politics, and that Blisner takes the effects of deindustrialization rather than discrimination as its subject. Asked in a recent interview to comment on ‘the anti-racist left’, Cedric Johnson suggests that it’s a mistake to think about phenomena like police violence (including the fact that Black people are disproportionately its target) or the huge prison population (and the fact that Blacks are so over-represented in it) as functions ‘exclusively or even primarily’ of ‘racism’.14 ‘The heart of the problem,’ he says, dates back to the process of deindustrialization and its consequences for working people – high levels of unemployment, even higher levels of underemployment and wage discipline in general (even for those who have full-time work). This has been bad news for the working class, and disproportionately bad news for black people for the completely uncontroversial reason that several hundred years of slavery and a century of Jim Crow have contributed to them being ‘overrepresented among unskilled workers’ and hence disproportionately harmed by the ‘elimination of well-paying, low-skilled manufacturing jobs via automation and deindustrialization’.15 And insofar as the long term response to this crisis has been not to create better paying jobs but to seek to provide equality of opportunity to compete for the few good ones, anti-discrimination has become the hegemon of social justice. It’s not for nothing that the neoliberal right16 and the neoliberal left17 both love diversity.

In other words, because both racism and now anti-racism have been used to shape the reserve army of labor and to deploy workers for maximum efficiency, it makes no more sense to think of the one (racism) as the problem than it does to think of the other (anti-racism) as the solution. Or to put the point more positively, we can only make sense of either of them, and of the hegemonic status of anti-discrimination more generally, by understanding them as ways of making capitalism work. What the resistance to capitalism thus requires is a certain scepticism about the moral outrage reliably produced by the demonstration of disproportionately raced, sexed and gendered outcomes. More precisely, it requires a certain skepticism about outrage itself, as well as about its kinder gentler cousins, sympathy and compassion.

Hence what’s politically important about Blisner is the same thing as what’s aesthetically important about it – its ability to produce the work’s autonomy (its wholeness) as a way of acknowledging without appealing to the experience of its reader, of acknowledging but rendering irrelevant (treating it almost as a kind of nostalgia) the power of the appeal itself. Its imagination of an anti-capitalist politics – one that sought to destroy the class system rather than render it more meritocratic – is embodied precisely in the indifference to both subject and reader that establishes its claim to aesthetic autonomy. In other words, its politics is its claim to be art, a claim we can make more perspicuous by contrasting Blisner to another significant (and exactly contemporary but explicitly documentary) photographic project, Matt Black’s 2014 The Geography of Poverty. Black has for a long time taken photographs of the poverty in California’s Central Valley. Several years ago, worried that people tended to think of that poverty as confined to certain areas of the country (as a problem that wasn’t, in effect, everywhere), he had the idea for an Instagram project: he would take photographs all around the US, posting them as he travelled, with the goal, as he describes it, of ‘get(ing) people that are on Instagram to picture themselves in those places’.18

One way, then, to get at what’s specific to Shea’s Blisner is to note that Black’s Geography of Poverty is explicitly committed to what I have argued Blisner rejects, the identificatory structure of the appeal: these people are in need of help, we need to imagine what it would be like to be them, we need to help them. Another way is by noting that Black’s understanding of his subject is poverty rather than the process or logic according to which both poverty and wealth are produced; Shea’s deindustrialization, by contrast, is a concept. Finally, Geography of Poverty has no interest in establishing an internal structure. It’s organized around an essentially additive idea of the whole. The problem Black sets out to solve is getting people to see that poverty was not just ‘happening in some weird place in the middle of nowhere . . . that’s just an outlier’ but is everywhere. What his project involves is in effect a geographical ‘all lives matter’; seeing exclusion as the problem, it establishes inclusion as the solution when, again by contrast, the logic of deindustrialization understands everyone as already included. LIC (if you’re looking at nonsite.org, that’s the view from Dan Shea’s roof) doesn’t exclude Blisner, it lives off Blisner; the two are constitutive of each other.

Another way to put this would be to say that Black’s idea of the whole is the US and thus the Geography project is structured externally by a route that took him more or less around the circumference of the country, a journey that, if it were extended, would take him around the globe, and that, as he notes, isn’t really (cannot really be) complete – new possibilities (on the road and, where the project exists, on the internet) are always open. Whereas Shea’s idea of the whole is capitalism, an idea that in principle can be made visible without ever going anywhere, and that he makes manifest by the internal, closed structure of the book. That is, the whole that matters in Blisner is a whole that must be understood rather than experienced or (more precisely) that must be understood in order to be experienced, and that in a crucial sense exists independent of our or anyone’s experience. The idea of this whole is embodied first in Blisner’s fictionality (the fact that the real people and real places it pictures are subsumed by an unreal town, so although there’s an important sense in which every picture in it is a picture of something, there’s an equally important sense in which the book as such is not a picture of anything) and, second, in its declaration of independence from its reader/beholder (the fact that its order belongs to it, not our experience of it, and that it not only makes no appeal to the viewer but even refuses the very idea of such an appeal).

That’s what I mean by saying that what distinguishes the politics of Blisner, IL from the politics of Geography of America is its aesthetics; its claim to be art rather than documentary. My point here is not about the relation of the aesthetic to the political as such. Obviously, they’re not identical; even if you think that art is just another way of doing politics, the fact that it’s one way among others (different, say, from giving policy speeches) would suggest its distinctiveness. And conversely, they’re not entirely separable; indeed the very idea that they can be separated is sometimes thought to imply a certain politics (usually a conservative one), and many works don’t even seek such separation. So when, in his Essays on Photography and Politics, a writer like David Levi-Strauss asks the rhetorical question ‘Why can’t beauty be a call to action’, his implication that it can be is obviously right.19 Just to stick with our current examples, many of Matt Black’s photographs are beautiful and they are a call to action, an exhortation to the viewers to do something about the poverty in our midst. But Blisner asserts its aesthetics by not calling on us to do anything. And today, that particular aesthetic – of the work that seeks to establish its internal coherence, that asserts itself as a whole – is an expression of a particular politics – one that in picturing the world as a whole, pictures it as organized by exploitation, by paying workers less than the value of what they produce. It’s as if Blisner achieves the form that marks it as having a class aesthetic only by refusing the call to action that would give it a role to play in a class politics. As if it makes no appeal to action not despite, but precisely because it pictures the world as organized by exploitation.

Why might that be? One kind of answer might plausibly gesture toward the critique of what Doug Henwood, Liza Featherstone and Christian Parenti several years ago called activistism. What they were describing was action taken with the best intentions in the world but without recourse to any analysis of the political economy producing the problem the actions were supposed to address, and thus tending to reproduce rather than resist the structures of neoliberal capital. Today for example, the complete compatibility of liberal movements like Teach for America and Black Lives Matter not only with each other but also with the charterization of American schools and the busting of teachers unions suggests the ways in which liberalism lends itself to neoliberalism. More generally, the anti-disparitarian orientation of a supposedly left politics would itself be an exemplary instance of activistism. The problem is not with the motives behind this kind of struggle for equality; it’s with the relation between those motives and the consequences of the actions they generate.

And this is equally true of Matt Black’s in many ways admirable Geography of Poverty project. The minute you understand yourself as ‘trying to put forgotten marginalized communities in the spotlight’20 – as if the problem is that capitalism forgets or marginalizes, as opposed to exploits the working class – you’ve committed yourself to a conception of both the political and the aesthetic that makes visible the fact of poverty at the expense precisely of the idea of exploitation.

This is why it makes both political and aesthetic sense for Shea – who began Blisner out of his anger at the coal industry and because, as he puts it, he ‘cared about’ these ‘people and about [their] struggle’ – to say now, about himself as an artist, ‘I don’t identify as an activist at all anymore’.21 This disidentification is not just personal, and it’s not a sign of discouraged quietism. Just the opposite. At this moment, to assert the difference – indeed the opposition – between the artist and the activist is to assert a conception of the aesthetic as the condition of possibility of action that would not be activistism. If we tend to identify the very idea of political art with the effort to try to get the beholder to do something, it’s as if – at this moment – the mark of a truly left political art is that it doesn’t try to get you to do anything. What it does instead is make it possible for you to understand something.

Leo Panitch has recently suggested that in the twenty-first century, reform ‘in terms of the old debate about reform versus revolution’ ‘is probably no longer possible within capitalism’.22 And, of course, it’s notoriously the case that in the US the very meaning of reform – school reform, welfare reform, pension reform, tax reform – is invoked with increasing frequency on behalf of technologies for facilitating rather than reversing the upward redistribution of wealth. Or, more precisely, on behalf of efforts to identify the public good with the logic of the market. This is true even of reforms that are presented as coming from the left. Reparations, for example (as Ken Warren has pointed out), essentially involve paying people what they’d have if they’d been treated fairly in the labour market, the housing market, the mortgage market, etc.23 And the identification of reform with access to markets (think of the current revival of the guaranteed minimum income) remains true even though one lesson of the Sanders campaign is that the actual left alternatives – taking housing, health care and education out of the market – turn out still to be attractive to millions of young people. So maybe it’s not that reform is now impossible but rather that it’s been reconfigured; instead of guaranteeing you the right to a house, it seeks to guarantee you the right to compete for a mortgage.

But revolution against capitalism doesn’t become more possible just because reform within capitalism (the effort to mitigate rather than legitimate exploitation) becomes less possible. It just becomes more necessary. Which is, I want to say, what Blisner understands. Or a little less dramatically, what Blisner understands – what the assertion of its form instead of and against the appeal to its beholder insists on, what the insistence on form instead of reform dramatizes – is the necessity of a politics that if it is not fundamentally anti-capitalist, is not anti-capitalist at all.

Blisner’s own relation to this necessity – actually the way it produces this necessity – is aesthetic in a Kantian mode, as a form of contemplation rather than an exhortation to do something.24 In other words, Blisner doesn’t and cannot say what the politics that I just described as ‘fundamentally anticapitalist’ might be. Rather, its inability to say what that politics might be is the condition of possibility of its saying what the point of that politics must be. It’s a kind of thought experiment in the relation between form and capitalism where the ambition to achieve the one expresses the desire to end the other. And where, conversely, success at ending the other would make the desire for the one irrelevant. You want form because you don’t know how to end capital; if you end capital you won’t want form. Or, a little more precisely, the desire for aesthetic form is both the desire to see the world as it is and to imagine the possibility of its being radically different. And if we were to succeed in making it different, the desire for form would become irrelevant; many things would be beautiful, none would be art.

This is why Shea’s choosing art against activism (form against reform) matters. The idea that art can be political in the sense of encouraging people to do the right political thing has always been a little problematic. (Sartre loved Guernica but ‘does anyone think,’ he asked, ‘that it won over a single heart to the Spanish cause?’25) Of course, one reason for this might have been that even if Picasso’s aesthetic ambitions in Guernica are perhaps less challenging than those of, say, his analytical cubist period, art (especially art since modernism) can be hard; you have to understand it in order to be won over by it, and you have to know a lot and look at a lot before you can understand it. But that’s not the only problem; indeed for our purposes that might even be understood as an advantage.

For insofar as the problem with activistism and the difference between the activist and the artist both involve the difficulty of figuring out the right political thing to do, and insofar as today we might say that the difficulty of figuring out what that is is every bit as vivid as the difficulty of doing it (see Syriza), it doesn’t make much sense to think of politics as easier than art. Just the opposite. It’s hard to make or even understand a masterpiece but harder still to understand what it would take to make a revolution, much less actually make one. Hence part of art’s power today is its ability to envision the possibility of (and necessity for) an act that we cannot yet quite identify, much less perform. Indeed, we might say today that for artists like Shea this aporetic relation between art and action can best be understood as the truth of both. Putting the point negatively, a successful revolution would make art unnecessary. Putting the point positively, every successful work of art reminds us that a revolution is what we need.

An earlier and quite different version of this essay was first published under the title ‘Picturing the Whole’ in the book made up of these photographs, Daniel Shea’s Blisner, IL (London: Fourteen-Nineteen, 2014). I’m grateful to him for permission to re-use some of the original material and, of course, for the work itself. Most of the photos here come from that book. With Shea’s permission, they have also been made available on nonsite.org.

1John Berger, About Looking, New York: Vintage International, 1991, p. 61.

2Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, New York: Picador, 2003, p. 45.

3Sontag, Regarding, p. 103.

4Sontag, Regarding, p. 76.

5Sontag, Regarding, p. 119.

6For data on the US and Illinois specifically, see the US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics online database at http://data.bls.gov.

7Al Barbarino, ‘Long Island City’s Renaissance’, Commercial Observer, 12 March 2013.

8Michael Fried, Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008, p.14.

9Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History, Volume III, London: Phaidon Press, 2014, p. 7.

10Interestingly, Sontag also prefers the photo in the book to the one on the museum wall since she thinks the ‘weight and seriousness’ of photographs of suffering ‘survive better in a book’ than they do in the ‘social situation’ of a gallery or museum visit. The emotions they produce don’t fade quite as fast.

11For a more extensive elaboration of this argument and discussion of many more artists, see Walter Benn Michaels, The Beauty of a Social Problem: Photography, Economy, Autonomy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

12Georg Lukács, Lenin: A Study on the Unity of His Thought, trans. by Nicholas Jacobs, London: Verso, 2009, p. 10.

13David Weigel, ‘Clinton in Nevada: “Not everything is about an economic theory”’, The Washington Post, 13 February 2016. She also pointed out that it wouldn’t end discrimination against the LGBT community or ‘make people feel more welcoming to immigrants’.

14Gregor Baszak, ‘Marxism through the back door: An interview with Cedric Johnson’, Platypus Review, 79, September 2015.

15This is Touré Reed’s account of Charles Killingworth’s 1968 argument in Jobs and Income for Negroes. See Toure Reed, ‘Why Moynihan Was Not So Misunderstood at the Time’, Nonsite, 17, 4 September 2015. Reed goes on to argue that ‘racism, though real and relevant, was not the principal cause of black poverty in the 1960s nor is it today’.

16For example, Goldman Sachs: ‘Diversity is at the very core of our ability to serve our clients well and to maximize return for shareholders’. See: http://www.goldmansachs.com/who-we-are/diversity-and-inclusion/.

17For example, every university in the United States. But here my own distinction begins to look pretty flimsy. When the people pictured on the Harvard website (http://diversity.college.harvard.edu) are just studying to become the people on the Goldman Sachs website, perhaps something even cruder than the distinction between left and right neoliberals is required: rich people love diversity.

18Olivier Laurent, ‘How One Photographer is Mapping America’s Poverty’, Time, 16 July 2015.

19David Levi Strauss, Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics, New York: Aperture, 2005, p. 9.

20Brennavan Sritharan, ‘Matt Black’s “Moral” Photography of America’s Sprawling Poverty’, British Journal of Photography, 28 August 2015.

21Lucas Foglia and Daniel Shea, ‘Interview: Daniel Shea on Blisner, Il’, photo-eye blog, 12 November 2014.

22Chris Hedges and Leo Panitch, ‘Days of Revolt: We Are All Greeks Now’, The Real News Network, 15 September 2015.

23Walter Benn Michaels and Kenneth Warren, ‘Reparations and Other Right-Wing Fantasies’, Nonsite, 11 February 2016.

24But here the feeling of beauty is imbricated in the understanding of the whole and the concept that in Kant is alien to the aesthetic is made integral to it.

25Jean-Paul Sartre, What is Literature, translated by Bernard Frechtman, Cambridge: Harvard, 1988, p. 28.