Chapter 1

Origins

Climbing ropes used to be a standard 45 metres long. By some cosmic coincidence, the Earth is reckoned to be 4.54 billion years old, which means that every metre on the rope represents roughly 100 million years of Earth history.

If you were to lay the rope out and mark some key moments on it, you’d find that free oxygen first appeared in the Earth’s atmosphere around the 23-metre mark—just over half way along the rope. The first animals appear at around 33 metres, and the first dinosaurs at 43 metres—very near the end of the rope. The first hominids (genus Homo) appear just 2.3 millimetres from the end of the rope. That’s the width of about twenty pages, looked at end-on, of the book you are holding in your hand.

One thing that is clear from this is that the Earth has been around for much longer than we have, and in its guise as the third rock from the sun there’s very little we can do to halt its march through the heavens. But we are a force to be reckoned with when it comes to the Earth as a home for human beings and the nine billion other species with which we share it. For 99 percent of our time on Earth—99 percent of those 2.3 millimetres—humans lived a hunting and gathering existence which impacted very little on the environment around them. Whatever impact there was would have been relatively minor and short-lived, and the environment’s recovery from the effects of nomadic human life was generally rapid and complete.

Most of our impact has therefore been in the last one percent of the last 2.3 millimetres of the 45-metre rope that represents the history of the Earth. So what has happened in that infinitesimally small slice of our time on Earth to give rise to a politics of the environment?

Agriculture

It is generally recognized that there have been two major moments of acceleration of human impact on the world around us, neither of which heralded a politics of the environment as such, but both of which increased the intensity of our impact. In doing so they laid the foundations for concern about the sustainability of ways of life, a concern which is central to environmental politics.

The first of these moments (though in truth it was less a ‘moment’ and more a process that lasted several thousand years) was the development of agriculture, which began about 12,000 years ago. Humans have long interacted with plants and animals for their sustenance, and the difference between hunting and gathering and farming is one of degree rather than of kind—though it is a difference that has an effect as far as the potential for intensity of impact is concerned. So hunter-gatherers follow herds and forage for plants and fruit, while farmers close-herd their animals and plant and cultivate deliberately. The main advantage farmers have is that they are able to extract more food from a smaller area. It is not clear that farming is an easier way of providing food than hunting and gathering, and this raises the question of why people started to farm in the first place. It is possible that it was a response to population pressures in localized areas where the land was no longer able to support a nomadic existence.

Either way, agriculture gave rise to two phenomena that lie at the heart of contemporary environmental concerns. The first is the intensification of the impact of human activity on the environment, and the question of how sustainable that activity is over the long term. Growing food on the same piece of land over a long period of time can lead to a deterioration of the land, and this can put its long-term future as a source of food in doubt. This is a problem of environmental sustainability. Environmentalists say that many of the issues we have to deal with today, like global warming—or climate change (the terms will be used indistinguishably)—have the same structure: human activity puts pressure on the environment to the point where its capacity to sustain a comfortable and relatively predictable life cannot be guaranteed. Farmers develop techniques to keep their land fertile, ranging from crop rotation, to organic fertilizers, to chemical fertilizers, and to genetic engineering. More generally, environmental politics is in part about the search for solutions to unsustainability and putting them into practice. So solutions for global warming run from rationing people’s carbon emissions, to better house insulation, to giant mirrors in orbit around the Earth to reflect the sun’s rays back into space.

And this introduces the second issue: how sustainable are these solutions to unsustainability? If it was indeed the case that agriculture was a response to population pressures, then it might just have sidestepped the problem rather than eradicated it. This is because agriculture allowed settled communities to develop and populations to grow, further intensifying impact. So, arguably, the solution to the problem simply made it worse. Similarly, some will say that giant mirrors in space deflect (literally) the problem rather than get to the root cause of it—the root cause being a continuous rise in greenhouse gas emissions from human activity.

Industry

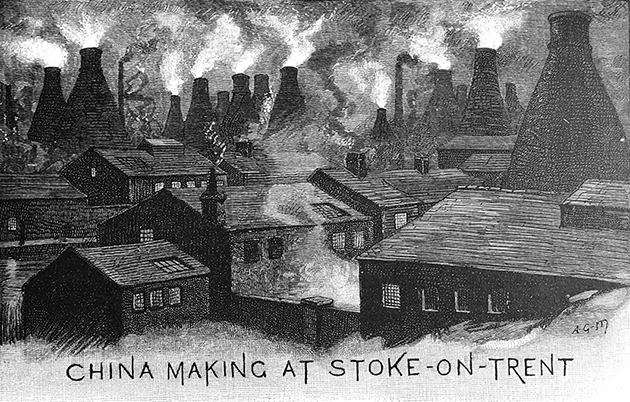

The second moment of acceleration of human impact on the environment occurred about 10,000 years after the development of the first agricultural communities—the Industrial Revolution (see Figure 1). Up to about the mid-18th century, human societies lived mainly off the energy available from the sun on a daily, weekly, monthly, seasonal basis. This is known as the flow of energy, which is different from the stock of energy. The stock of energy is what is stored up over a period of time—such as the energy in the wood in a tree. Energy stocks are very useful because they enable more work to be done in a shorter period of time than is possible with just the flow of energy.

1. Pollution from pottery kilns in 19th-century Stoke-on-Trent (UK).

It is helpful to think of this kind of energy as ‘stored sunlight’. Some of this sunlight has been stored for a short period of time—like the wood in a tree, for example. This takes us back no more than a few decades into the storehouse. Other sunlight, in the form of coal and oil, has been stored for much longer—millions of years. Very small amounts of coal have been used for domestic purposes since about 3500 bc (in China), and the Romans used it extensively in Britain during their long occupation. Wherever it has been easily accessible it has been used, but it was not until we began to mine and burn coal systematically in the middle of the 18th century, and, about a hundred years later in 1850, to extract petroleum, that we began seriously to deplete the sunlight storehouse—with two main consequences that have contributed to the rise of environmental politics.

The first consequence is a concern about resources, and the second relates to the unintended consequences of our actions. It would be wrong to say that environmental politics is only about resource use, but it is certainly a big part of this kind of politics. More particularly, there is an important distinction between renewable and non-renewable resources. Fossil fuels are non-renewable resources, which are therefore finite. Finite resources will, by definition, run out at some point. This brings the issue of sustainability back into view. Much of what we have achieved over the past 250 years has been made possible by the use of fossil fuels, but if these are due to run out then the sustainability of the civilization that relies on them must be in question. One possible solution is to replace a non-renewable resource with another—uranium for oil, for example. This would give us nuclear energy rather than fossil-fuelled energy. This might buy us some time, but it would not be a sustainable solution in the long term—unless technological advances were made that could spin out the viability of nuclear energy far into the future. Debates over the degree to which technology can help us meet the challenge of sustainability are indeed a key element in environmental politics. There are, though, those who argue that unsustainability is more a political than technological problem, more to do with how we organize our lives and what we expect out of them than about the application of science. These critics doubt the capacity of the ‘technological fix’ to solve our sustainability problems, and argue instead for changes in the behaviour and objectives of individuals and organizations along sustainability principles.

Another solution to the energy problem is to make a move to renewable resources. The advantage of renewables is that they never run out, but a potential disadvantage is that, from an energy point of view, it is unclear whether they can power the lifestyles that so-called developed societies have become accustomed to. So is there a trade-off between sustainability and prosperity? Will high-energy societies always be unsustainable societies? These are the kinds of questions that make environmental politics unlike any other politics. There is no other politics that concerns itself centrally with the relationship between humans and their environment, and with the question of how to regulate that relationship so it is sustainable over the long term.

The second feature of the Industrial Revolution which has had an impact on the development and nature of environmental politics is a growing realization of the potential force of the unintended consequences of our actions. When we first started burning coal and oil no-one suspected that a build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere would lead to a rise in average global temperature—this was an unintended consequence of the burning of fossil fuels. Many of our actions have unintended consequences, of course, but as the scale of our impact on our environment grows, the potential for harm caused by these consequences increases correspondingly. As well as increasing and accelerating the intensity of our impact on the environment, the Industrial Revolution also broadened the potential scope of that impact. As societies and civilizations grew, in great part as a result of the development of agriculture discussed earlier, their impact grew. There is evidence that some of these societies collapsed as a result of resource overuse—examples often cited are the Mayan civilization of Latin America in the 8th and 9th centuries ad, and Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean in the mid-18th century. These examples are contested, and the Easter Island collapse, for example, is sometimes put down to disease brought in by European visitors rather than unsustainable resource use.

Be that as it may, these are examples of unintended consequences and, while they were obviously disastrous for the people concerned, the impacts were only felt at a ‘local’ level. What is striking about the Industrial Revolution is that it gave rise to an unintended consequence with a global reach—global warming. No other species has the capacity to affect the planet as a whole, and it took the human species until now to realize this potential. This is why the Industrial Revolution is such a significant historical moment in the development of environmental politics—and particularly the possibility of a global environmental politics. So far-reaching has human impact on the environment become, indeed, that it has been suggested that we have set in train a whole new geological epoch—the ‘Anthropocene’. We will look at this claim and its implications in more detail in Chapter 5.

Revolution and reaction

The Industrial Revolution was itself made possible in part by the intellectual revolution that took place in Europe around the 18th century—the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment saw a burgeoning of the scientific method, and of the belief in the capacity of rational thought to explain the workings of the natural world. For some scientists of the time like Francis Bacon this translated into the ambition to control nature, and to submit it (or ‘her’ as he referred to it) to the will of human beings. Once people began to look for the causes of our environmental problems in the contemporary era, this attitude of domination looked as though it could be part of the problem, as it set nature apart from human beings and constructed it as an enemy to be conquered.

In the 19th century there was a reaction in Europe to the Industrial Revolution which went (and goes) by the name of Romanticism, and Romanticism has played a role in the development of contemporary environmental politics. Romantics in the 19th century railed against what they saw as the ugliness of industrialization and the way in which the primal forces of nature were being subdued by the rational mind and actions of ‘man’. Around this time, ideas of the ‘noble savage’ were popular among Romantics, a person unsullied by the modern world and instinctively in tune with the natural world. There were also concerns about scientists ‘playing God’ with nature and suffering the consequences. This is the theme of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, whose alternative title is—evocatively—‘The Modern Prometheus’. Prometheus, it will be remembered, was the Titan who stole fire from Zeus and was punished for it. This warning against humans overreaching their ‘natural’ capacities has its echoes today in the belief among some in the environmental movement that our problems are caused by too much of a separation between nature and human beings—that we see ourselves as apart from rather than a part of the natural world. Sometimes this view is accompanied by a harking back to the hunter-gatherer period of human existence, as a time at which humans and nature were in harmony with one another. From this point of view, the agricultural and industrial epochs drove a progressively deep wedge between humans and nature, and the surest way of healing the rift, it is sometimes said, is to draw on the well of Romanticism that sees humans as part of nature.

The same century saw the development of a scientific route to a similar conclusion regarding humans’ relation to nature, and it is important to recognize this early contribution of science to environmentalism since science plays a key role in contemporary environmental politics. In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, where he showed that the present diversity of life is caused by evolution and natural selection, and that humans are descended from apes. This challenged the dominant view in Christianity that humans are made in the image of God and are fundamentally different to the rest of ‘creation’. Thus Darwin reached the same conclusion as the Romantics by a different route—that humans are a part of nature rather than apart from it.

Darwin’s work had a related effect that has influenced the development of environmental politics—a ‘decentring’ of the human being. Back in 1543 Copernicus had published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolution of the Celestial Spheres), in which he argued that the Earth goes round the Sun rather than vice versa. This was an early intimation that the Earth and the humans who live on it are not special—confirmed by Darwin’s account of humans being descended from apes. In this same century, Ernst Haeckel first used the word ‘ecology’, intended to designate the science of the study of the relationships between organisms rather than their location in a hierarchy. This served to emphasize the interdependence of organisms—including the human organism—on one another. All these developments helped to destabilize the dominant view of ‘human exceptionalism’, the idea that the world was made for the benefit of human beings, and the related view that humans had a right to do whatever they wanted to it.

In one sense, though, human exceptionalism is an important feature of contemporary environmental politics. It is generally believed that the human animal is the only animal that can systematically (as opposed to occasionally) reflect on the world around it, act ‘beyond instinct’, and make meaningful, long-term choices. This gives us the capacity to understand the causes of environmental problems, develop policies to deal with them, and put those policies into action. Thus the Enlightenment and the 19th century gave us some of the key building blocks for today’s environmental politics: a series of environmental problems rooted in industrialization, the capacity to analyse those problems and devise solutions to them, and an ambivalent view as to whether these solutions entail more or less of an attempt to control the world around us.

The long 19th century

These 19th-century developments are bracketed by two further legacies which have left an enduring mark on today’s environmental politics: the idea of scarcity, and the first stirrings of a politics of energy. In the midst of a century of burgeoning plenty—even if very unequally shared—Thomas Malthus’ argument in his An Essay on the Principle of Population that population multiplies geometrically and food arithmetically, and so population will eventually outstrip the food supply, struck an unusual chord. Malthus’ point was that scarcity is a fundamental feature of the human condition rather than a temporary or contingent issue that can be overcome. This was a direct challenge to the Enlightenment idea, embodied in political theories such as Marxism, that things would always get better, and this challenge resurfaced in the 1970s in the guise of the important ‘limits to growth’ thesis which we will look at shortly.

Energy has come to be a fundamental issue in environmental politics, especially in regard to debates over renewable and non-renewable forms, the desirability of nuclear energy, disputes over the siting of wind turbines, and so on. Whatever its source, energy is fundamental to our lives, and, therefore, from a ‘green’ point of view, to our politics. This was first pointed out by the German chemist, Wilhelm Ostwald, in the late 19th century, who argued that we can do nothing without energy, and he developed an overarching theory that explained the development of human civilization in terms of the control of energy for human purposes. The idea was taken up by, among others, Frederick Soddy, English Nobel Prize winning radiochemist, who created an economic theory based on the laws of thermodynamics, representing a set of non-negotiable physical limits within which any politics or economics must operate. Once again, the notion of limits was taken up in the 1970s and has come to be a key—if disputed—reference point in contemporary environmental politics.

The idea that human possibilities are limited by circumstance and capacity is generally taken to be sign of conservatism, of right-wing thinking. We tend, today, to associate environmentalists with the left of the political spectrum, but it is important to note that in the early part of the 20th century some ‘back to the land’ movements in Europe were associated with the right. This is because ‘the land’ was seen in terms of the land of a particular nation rather than land in general, so looking after the land, being rooted in it, amounted to a defence of the nation and its culture and history. Thus the ‘environmentalists’ of this period were often conservatives and nationalists.

The 1960s and 1970s

There will always be disputes about when environmental politics ‘properly speaking’ began, but if we think of it as a jigsaw, then some time around the 1960s and 1970s the pieces began to come together: a growing awareness that negative environmental impacts might be a result of a mistaken whole development path, rather than local and isolated difficulties; and a political movement coalescing around those problems, offering an alternative political platform. One key moment in this process was the publication of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, about the impact of agricultural pesticides on the environment. The title of the book evokes the silence that would result from declining bird populations from pesticide poisoning—a picture that captivated large swathes of the American people, exposing them to environmental concerns as never before. A second moment was on 24 December 1968, when astronaut William Anders took the famous ‘Earthrise’ photograph from Apollo 8 as it swung round from behind the moon (see Figure 2). This picture captured the vulnerability of the blue, green, and white planet Earth as it hung in the blackness of space—an image that has adorned many a book cover, NGO logo, and PowerPoint presentation since.

A third crucial moment was the publication of The Limits to Growth report in 1972 (updated in 1992 and 2004). A key theme of this chapter, and of environmental politics in general, is how best to make use of the resources available to us. Underlying that question is another one: are these resources limited or not? This is a complicated question which we will explore further in Chapter 2, but the basic thesis of the ‘Limits’ team is that infinite growth in a finite system is impossible. The finite system in question is the Earth (whose finitude is graphically depicted in the Apollo 8 Earthrise photograph), and the infinite growth refers to an infinitely growing economy. The idea that there might be limits to how far an economy can grow puts environmental politics on a collision course with most mainstream politics, where a growing economy (increasing gross domestic product—GDP) is regarded as a sign of success.

2. ‘Earthrise’ photograph taken from Apollo 8, 24 December 1968.

Another important feature of the ‘Limits’ report was that it analysed the global system as a whole. A common feature of the environmental and resource problems encountered throughout human history up until the last half century or so is that they were local and/or regional. We saw that resource scarcity might have been the reason for the collapse of the Mayan and Easter Island civilizations, among others, but, however disastrous this was for the Mayans and the Easter Islanders, the causes and consequences of collapse were confined to those regions. There were always more resources ‘somewhere else’. The lesson from The Limits to Growth is that—barring interplanetary travel—there is no ‘somewhere else’ as far as resources, and space to grow food and accommodate waste are concerned. Around this time, Kenneth Boulding coined the term ‘Spaceship Earth’ to convey the idea of a self-contained system, wholly reliant for its survival on what it carries with it and unable to count on outside help. These thoughts raised the stakes as far as our relationship with our environment is concerned, making it clear to some that the margin for error was getting increasingly small—a concern which has a particular and pressing form in the shape of global warming.

But all these are ‘merely’ ideas. Politics needs people to enact these ideas in the political arena, and two rather different mobilizations have taken place, giving rise to contrasting types of environmental politics. The first is described by the so-called ‘post-material’ thesis, most thoroughly developed by Ronald Inglehart. According to this thesis, as societies become more materially affluent, their members are freed from having to spend all their time satisfying their basic needs, and have the time and resources to devote to post-material values such as autonomy and self-expression. Environmental concerns are sometimes regarded as a ‘luxury extra’, to be attended to once more pressing and material concerns have been dealt with—an ideal issue area to attract Inglehart’s post-materialists.

On this reading a precondition for the development of environmental politics is material affluence, but there is a very different type of environmental politics which is rooted in the opposite circumstance: material deprivation, and livelihoods threatened by environmental damage and destruction. It is often said that post-material environmentalism is characteristic of the global North, while livelihood environmentalism is typical of the global South. (The terms ‘global North’ and ‘global South’ are only partly geographical; here they refer to the distinction between developed and developing countries—so Australia is counted as a member of the ‘global North’ even though it lies in the southern hemisphere). While this is accurate up to a point, it is also true to say that there are post-materialists in the global South (the burgeoning middle-classes of India and China, for example) and people in the global North whose livelihoods are threatened by environmental degradation (living near toxic waste dumps, for example). We will look more closely at these different kinds of environmental politics in Chapter 4.

All of this strongly suggests that the 1970s is an important decade when it comes to locating the origins of environmental politics, and the hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that many of the best-known international environmental organizations and Green political parties were founded around this time. There are often disputes about the exact dates of the founding of organizations, since the names by which they have come to be known are not always the names of the groups from which they emerged. Bearing that in mind, we can say that Friends of the Earth was founded in 1969, and Greenpeace in 1972, while the two parties that vie for the accolade of ‘first Green party’, in Tasmania and New Zealand (the United Tasmania Group and the Values Party, respectively) were both founded in 1972. Perhaps the best-known Green party of all, die Grünen, the German Greens, held its first party congress in 1980, and made a breakthrough in the Federal elections in 1983 when it won 5.6 percent of the vote and twenty-seven seats in the Bundestag. This showed other Green parties that electoral success was a real possibility, and since then Green representatives have been elected to public office at local, regional, national, and international level in many countries around the world. We will look at these developments, and analyse the factors that make for Green party electoral success and failure, in some detail in Chapter 3.

We started with a rope 45 metres long, representing the 4.54 billion-year history of the Earth. Human impact on the Earth occupies about 1 per cent of the last 2.3 millimetres of that rope, and our discussion in this chapter shows that environmental politics has been with us for a tiny fraction of that 1 per cent. In that short space of time it has made a dramatic impact on the political landscape in many ways and at many levels. The rest of this book is devoted to exploring, explaining, and discussing this impact, with Chapter 2 being about the ideas underpinning it.