The several hundred national and regional cultures of the world can be roughly classified into three groups: task-oriented, highly organized planners (linear-active); people-oriented, loquacious interrelators (multi-active); and introverted, respect-oriented listeners (reactive). Italians see Germans as stiff and time-dominated; Germans see Italians gesticulating in chaos; the Japanese observe and quietly learn from both.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, we have many nation–states and different cultures, but enduring misunderstandings arise principally when there is a clash of category rather than nationality. For example, Germany and the Netherlands experience national friction, but they understand and cooperate with each other because they are both linear-active. Friction between Korea and Japan occasionally borders on hatred, but their common reactive nature leads to blossoming bilateral trade.

Let us examine for a moment the number and variety of cultures as they now stand and consider how classification and adaptation might guide us toward better understanding.

There are over 200 recognized countries or nation-states in the world, and the number of cultures is considerably greater because of strong regional variations. For instance, marked differences in values and behavior are observable in the north and south of such countries as Italy, France and Germany, while other states are formed of groups with clearly different historical backgrounds (the United Kingdom with her Celtic and Saxon components, Fiji with her Polynesians and Indians, Russia with numerous subcultures such as Tatar, Finnic, Chechen, etc.).

In a world of rapidly globalizing business, Internet electronic proximity and politico-economic associations, the ability to interact successfully with foreign partners in the spheres of commercial activity, diplomatic intercourse and scientific interchange is seen as increasingly essential and desirable. Cross-cultural training followed by international experience goes a long way toward facilitating better relationships and reducing misunderstandings. Ideally, the trainee acquires deepening insights into the target (partner’s) culture and adopts a cultural stance towards the partner/colleague, designed (through adaptation) to fit in suitably with the attitudes of the other.

The question then arises as to how many adaptations or stances are required for effective international business relations. It is hardly likely that even the most informed and adaptable executive could envisage assuming 200 different personalities! Even handling the different national types on European Union (EU) committees and working groups has proved a daunting task for European delegates, not to mention the chairpersons.

Such chameleon-like behavior is out of the question and unattainable, but the question of adaptation remains nevertheless important. The reticent, factual Finn must grope toward a modus operandi with the loquacious, emotional Italian. Americans will turn over many more billions in trade if they learn to communicate effectively with the Japanese and Chinese.

Assuming a suitable cultural stance would be quickly simplified if there were fewer cultural types to familiarize oneself with, can we boil down 200 to 250 sets of behavior to 50 or 20 or 10 or half a dozen? Cross-culturalists have grappled with this problem over several decades. Some have looked at geographical divisions (north, south, east and west), but what is “Eastern” culture? And is it really unified? People can be classified according to their religion (Muslim, Christian, Hindu) or ethnic/racial origin (Caucasian, Asian, African, Polynesian, Indian, Eskimo, Arab), but such nomenclatures contain many inconsistencies—Christian Norwegians and Lebanese, Caucasian Scots and Georgians, Muslim Moroccans and Indonesians, and so on. Other classification attempts, such as professional, corporate or regional, have too many subcategories to be useful. Generational culture is important but ever changing. Political classification (Left, Right, Centrist) has many (changeable) hues, too.

Writers such as Geert Hofstede have sought dimensions to cover all cultures. His four dimensions included power distance, collectivism versus individualism, femininity versus masculinity and uncertainty avoidance. Later he added long-term versus short-term orientation. Edward T. Hall classified groups as mono-chronic or polychronic, high or low context and past- or future-oriented. Alfons Trompenaars’ dimensions categorized universalist versus particularist, individualist versus collectivist, specific versus diffuse, achievement versus ascription and neutral versus emotional or affective. The German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies dwelt on Gemeinschaft versus Gesellschaft cultures. Florence Kluckholn saw five dimensions/attitudes to problems: time, Nature, nature of man, form of activity and relation to one’s cultural compatriots. Samuel Huntington drew fault lines between civilizations—West European, Islam, Hindu, Orthodox, Japanese, Sinic and African.

The need for a convincing categorization is obvious. It enables us to

![]() predict a culture’s behavior,

predict a culture’s behavior,

![]() clarify why people did what they did,

clarify why people did what they did,

![]() avoid giving offense,

avoid giving offense,

![]() search for some kind of unity,

search for some kind of unity,

![]() standardize policies, and

standardize policies, and

![]() perceive neatness and Ordnung.

perceive neatness and Ordnung.

Sven Svensson is a Swedish businessman living in Lisbon. A few weeks ago he was invited by a Portuguese acquaintance, Antonio, to play tennis at 10:00 A.M. Sven turned up at the tennis court on time, in tennis gear and ready to play.

Antonio arrived half an hour late, in the company of a friend, Carlos, from whom he was buying some land. They had been discussing the purchase that morning and had prolonged the discussion, so Antonio had brought Carlos along in order to finalize the details during the journey. They continued the business while Antonio changed into his tennis clothes, with Sven listening to all they said. At 10:45 they got on the court, and Antonio continued the discussion with Carlos while hitting practice balls with Sven.

At this point another acquaintance of Antonio’s, Pedro, arrived to confirm a sailing date with Antonio for the weekend. Antonio asked Sven to excuse him for a moment and walked off the court to talk to Pedro. After chatting with Pedro for five minutes, Antonio resumed his conversation with the waiting Carlos and eventually turned back to the waiting Sven to begin playing tennis at 11:00. When Sven remarked that the court had only been booked from 10:00 to 11:00, Antonio reassured him that he had phoned in advance to rebook it until noon. No problem.

It will probably come as no surprise to you to hear that Sven was very unhappy about the course of events. Why? He and Antonio live in two different worlds or, to put it more exactly, use two different time systems. Sven, as a good Swede, belongs to a culture which uses linear-active time—that is, he does one thing at a time in the sequence he has written down in his date book. His schedule that day said 8:00 A.M. get up, 9:00 breakfast, 9:15 change into tennis clothes, 9:30 drive to the tennis court, 10:00–11:00 play tennis, 11:00–11:30 beer and shower, 12:15 lunch, 2:00 P.M. go to the office, and so on.

Antonio, who had seemed to synchronize with him for tennis from 10:00 to 11:00, had disorganized Sven’s day. Portuguese like Antonio follow a multi-active time system, that is, they do many things at once, often in an unplanned order.

Multi-active cultures are very flexible. If Pedro interrupted Carlos’ conversation, which was already in the process of interrupting Sven’s tennis, this was quite normal and acceptable in Portugal. It is not acceptable in Sweden, nor is it in Germany or Britain.

Linear-active people, like Swedes, Swiss, Dutch and Germans, do one thing at a time, concentrate hard on that thing and do it within a scheduled time period. These people think that in this way they are more efficient and get more done. Multi-active people think they get more done their way.

Let us look again at Sven and Antonio. If Sven had not been disorganized by Antonio, he would undoubtedly have played tennis, eaten at the right time and done some business. But Antonio had had breakfast, bought some land, played tennis and confirmed his sailing plans, all by lunchtime. He had even managed to rearrange the tennis booking. Sven could never live like this, but Antonio does, all the time.

Multi-active people are not very interested in schedules or punctuality. They pretend to observe them, especially if a linear-active partner insists. They consider reality to be more important than man-made appointments. Reality for Antonio that morning was that his talk with Carlos about land was unfinished. Multi-active people do not like to leave conversations unfinished. For them, completing a human transaction is the best way they can invest their time. So he took Carlos to the tennis court and finished buying the land while hitting balls. Pedro further delayed the tennis, but Antonio would not abandon the match with Sven. That was another human transaction he wished to complete. So they would play till 12:00 or 12:30 if necessary. But what about Sven’s lunch at 12:15? Not important, says Antonio. It’s only 12:15 because that’s what Sven wrote in his date book.

A friend of mine, a BBC producer, often used to visit Europe to visit BBC agents. He never failed to get through his appointments in Denmark and Germany, but he always had trouble in Greece. The Greek agent was a popular man in Athens and had to see so many people each day that he invariably ran overtime. So my friend usually missed his appointment or waited three or four hours for the agent to turn up. Finally, after several trips, the producer adapted to the multi-active culture. He simply went to the Greek agent’s secretary in late morning and asked for the agent’s schedule for the day. As the Greek conducted most of his meetings in hotel rooms or bars, the BBC producer would wait in the hotel lobby and catch him rushing from one appointment to the next. The multiactive Greek, happy to see him, would not hesitate to spend half an hour with him and thus make himself late for his next appointment.

When people from a linear-active culture work together with people from a multi-active culture, irritation results on both sides. Unless one party adapts to the other—and they rarely do—constant crises will occur. “Why don’t the Mexicans arrive on time?” ask the Germans. “Why don’t they work to deadlines? Why don’t they follow a plan?” The Mexicans, on the other hand, ask, “Why keep to the plan when circumstances have changed? Why keep to a deadline if we rush production and lose quality? Why try to sell this amount to that customer if we know they aren’t ready to buy yet?”

Recently I visited a wonderful aviary in South Africa where exotic birds of all kinds were kept in a series of 100 large cages, to which the visiting public had direct access. There was plenty of room for the birds to fly around and it was quite exciting for us to be in the cage with them. You proceeded, at your leisure, from cage to cage, making sure all the doors were closed carefully.

Two small groups of tourists—one consisting of four Germans and the other of three French people—were visiting the aviary at the same time as we were. The Germans had made their calculations, obviously having decided to devote 100 minutes to the visit; consequently they spent one minute in each cage. One German read the captions, one took photographs, one videoed and one opened and closed doors. I followed happily in their wake. The three French people began their tour a few minutes later than the Germans but soon caught up with them as they galloped through the cages containing smaller birds. As the French were also taking pictures, they rather spoiled cage 10 for the Germans, as they made a lot of noise and generally got in the way. The Germans were relieved when the French rushed on ahead toward the more exciting cages.

The steady German progress continued through cages 11 to 15. Cage 16 contained the owls (most interesting). There we found our French friends again, who had occupied the cage for five minutes. They filmed the owls from every angle while the Germans waited their turn. When the French eventually rushed out, the Germans were five minutes behind schedule. Later on, the French stayed so long with the eagles in cage 62 that the Germans had to bypass them and come back to see the eagles later. They were furious at this forced departure from their linear progression, and eventually finished their visit half an hour late. By then the French had departed, having seen all they were interested in.

A study of attitudes toward time in a Swiss–Italian venture showed that, after some initial quarreling, each side learned something from the other. The Italians finally admitted that adherence at least in theory to schedules, production deadlines and budgets enabled them to clarify their goals and check on performances and efficiency. The Swiss, on the other hand, found that the more flexible Italian attitude allowed them to modify the timetable in reaction to unexpected developments in the market, to spot deficiencies in the planning that had not been evident earlier, and to make vital last-minute improvements with the extra time.

Germans, like the Swiss, are very high on the linear-active scale, since they attach great importance to analyzing a project, compartmentalizing it, tackling each problem one at a time in a linear fashion, concentrating on each segment and thereby achieving a near-perfect result. They are uneasy with people who do not work in this manner, such as Arabs and those from many Mediterranean cultures.

Americans are also very linear-active, but there are some differences in attitude. As Americans live very much in the present and race toward the near future, they sometimes push Germans into action before the latter want to act. Germans are very conscious of their history and their past and will often wish to explain a lot of background to American partners to put present actions in context. This often irritates Americans who want to “get on with it.”

Figure 3.1 gives a suggested ranking on the linear/multi-active scale, showing some rather surprising regional variations. German and other European influences in Chile have caused Chileans to be less multi-active than, for instance, Brazilians or Argentineans. The differences in behavior between northern and southern Italians are well documented. Australians, with a large number of Southern European immigrants, are becoming less linear-active and more extroverted than most northern peoples.

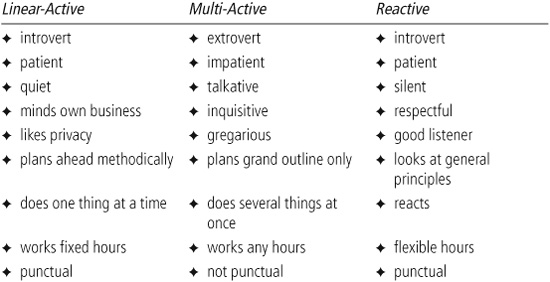

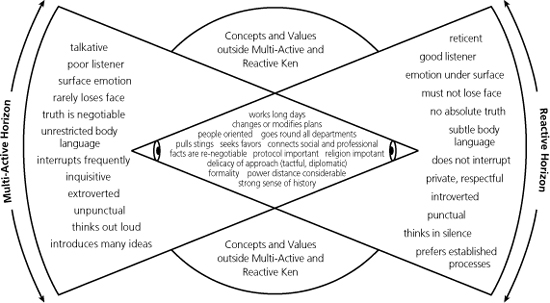

Figure 3.2 lists the most common traits of linear-active, multi-active and reactive cultures.

Japan belongs to the group of reactive, or listening, cultures, the members of which rarely initiate action or discussion, preferring to listen to and establish the other’s position first, then react to it and formulate their own.

2. Americans (WASPs)*

3. Scandinavians, Austrians

4. British, Canadians, New Zealanders

5. Australians, South Africans

6. Japanese

7. Dutch, Belgians

8. American subcultures (e.g., Jewish, Italian, Polish)

9. French, Belgians (Walloons)

10. Czechs, Slovenians, Croats, Hungarians

11. Northern Italians (Milan, Turin, Genoa)

12. Chileans

13. Russians, other Slavs

14. Portuguese

15. Polynesians

16. Spanish, Southern Italians, Mediterranean peoples

17. Indians, Pakistanis, etc.

18. Latin Americans, Arabs, Africans

*White Anglo-Saxon Protestants

Figure 3.1 Linear-Active/Multi-Active Scale

Figure 3.2 Common Traits of Linear-Active, Multi-Active, and Reactive Categories

Reactive cultures are also found in China, Taiwan, Singapore, Korea, Turkey and Finland. Several other East Asian countries, although occasionally multiactive and excitable, have certain reactive characteristics. In Europe, only Finns are strongly reactive, but Britons, Turks and Swedes fall easily into “listening mode” on occasion.

Reactive cultures listen before they leap. Reactive cultures are the world’s best listeners in as much as they concentrate on what the speaker is saying, do not let their minds wander (difficult for Latins) and rarely, if ever, interrupt a speaker while the discourse or presentation is on-going. When it is finished, they do not reply immediately. A decent period of silence after the speaker has stopped shows respect for the weight of the remarks, which must be considered unhurriedly and with due deference.

Even when representatives of a reactive culture begin their reply, they are unlikely to voice any strong opinion immediately. A more probable tactic is to ask further questions on what has been said in order to clarify the speaker’s intent and aspirations. Japanese, particularly, go over each point many times in detail to make sure there are no misunderstandings. Finns, although blunt and direct in the end, shy away from confrontation as long as they can, trying to formulate an approach that suits the other party. The Chinese take their time to assemble a variety of strategies that will avoid discord with the initial proposal.

Reactives are introverted; they distrust a surfeit of words and consequently are adept at nonverbal communication. This is achieved by subtle body language, worlds apart from the excitable gestures of Latins and Africans. Linear-active people find reactive tactics hard to fathom because they do not slot into the linear system (question/reply, cause/effect). Multi-active people, used to extroverted behavior, find them inscrutable—giving little or no feedback. The Finns are the best example of this behavior, reacting even less than the Japanese, who at least pretend to be pleased.

In reactive cultures the preferred mode of communication is monologue—pause—reflection—monologue. If possible, one lets the other side deliver its monologue first. In linear-active and multi-active cultures, the communication mode is a dialogue. One interrupts the other’s monologue with frequent comments, even questions, which signify polite interest in what is being said. As soon as one person stops speaking, the other takes up his or her turn immediately, since the Westerner has an extremely weak tolerance for silence.

People belonging to reactive cultures not only tolerate silences well but regard them as a very meaningful, almost refined, part of discourse. The opinions of the other party are not to be taken lightly or dismissed with a snappy or flippant retort. Clever, well-formulated arguments require—deserve—lengthy silent consideration. The American, having delivered a sales pitch in Helsinki, leans forward and asks, “Well, Pekka, what do you think?” If you ask Finns what they think, they begin to think. Finns, like Asians, think in silence. An American asked the same question might well pipe up and exclaim, “I’ll tell you what I think!”—allowing no pause to punctuate the proceedings or interfere with Western momentum. Asian momentum takes much longer to achieve. One can compare reactions to shifting the gears of a car, where multi-active people go immediately into first gear, which enables them to put their foot down to accelerate (the discussion) and to pass quickly through second and third gears as the argument intensifies. Reactive cultures prefer to avoid crashing through the gearbox. Too many revs might cause damage to the engine (discussion). The big wheel turns slower at first and the foot is put down gently. But when momentum is finally achieved, it is likely to be maintained and, moreover, it tends to be in the right direction.

The reactive “reply-monologue” will accordingly be context centered and will presume a considerable amount of knowledge on the part of the listener (who, after all, probably spoke first). Because the listener is presumed to be knowledgeable, Japanese, Chinese and Finns will often be satisfied with expressing their thoughts in half-utterances, indicating that the listener can fill in the rest. It is a kind of compliment one pays one’s interlocutor. At such times multi-active, dialogue-oriented people are more receptive than linear-oriented people, who thrive on clearly expressed linear argument.

Reactive cultures not only rely on utterances and semi-statements to further the conversation, but they indulge in other Eastern habits that confuse the Westerner. They are, for instance, “roundabout,” using impersonal pronouns (“one is leaving”) or the passive voice (“one of the machines seems to have been tampered with”), either to deflect blame or with the general aim of politeness.

As reactive cultures tend to use names less frequently than Westerners, the impersonal, vague nature of the discussion is further accentuated. Lack of eye contact, so typical of the East, does not help the situation. The Japanese, evading the Spaniard’s earnest stare, makes the latter feel that they are being boring or saying something distasteful. Asian inscrutability (often appearing on a Finn’s face as a sullen expression) adds to the feeling that the discussion is leading nowhere. Finns and Japanese, embarrassed by another’s stare, seek eye contact only at the beginning of the discussion or when they wish their opponent to take their “turn” in the conversation.

Japanese delegations in opposition with each other are often quite happy to sit in a line on one side of the table and contemplate a neutral spot on the wall facing them as they converse sporadically or muse in joint silence. The occasional sidelong glance will be used to seek confirmation of a point made. Then it’s back to studying the wall again.

Small talk does not come easily to reactive cultures. While Japanese and Chinese trot out well-tried formalisms to indicate courtesy, they tend to regard questions such as “Well, how goes it?” as direct questions and may take the opportunity to voice a complaint. On other occasions their overlong pauses or slow reactions cause Westerners to think they are slow witted or have nothing to say. Turks, in discussion with Germans in Berlin, complained that they never got the chance to present their views fully, while the Germans, for their part, thought the Turks had nothing to say. A high-ranking delegation from the Bank of Finland once told me that, for the same reason, their group found it hard to get a word in at international meetings. “How can we make an impact?” they asked. The Japanese suffer more than any other people in this type of gathering.

The Westerner should always bear in mind that the actual content of the response delivered by a person from a reactive culture represents only a small part of the significance surrounding the event. Context-centered utterances inevitably attach more importance not to what is said, but how it is said, who said it and what is behind what is said. Also, what is not said may be the main point of the reply.

Self-disparagement is another favorite tactic of reactive cultures. It eliminates the possibility of offending through self-esteem; it may draw the opponent into praising the Asian’s conduct or decisions. The Westerner must beware of presuming that self-disparagement is connected with a weak position.

Finally, reactive cultures excel in subtle, nonverbal communication, which compensates for the absence of frequent interjections. Finns, Japanese and Chinese alike are noted for their sighs, almost inaudible groans and agreeable grunts. A sudden intake of breath in Finland indicates agreement, not shock, as it would in the case of a Latin. The “oh,” “ha” or “e” of the Japanese is a far surer indication of concurrence than the fixed smile they often assume.

Reactive people have large reserves of energy. They are economical in movement and effort and do not waste time reinventing the wheel. Although they always give the impression of having power in reserve, they are seldom aggressive and rarely aspire to leadership (in the case of Japan, this is somewhat surprising in view of her economic might). France, Britain, and the USA, on the other hand, have not hesitated to seize world leadership in periods of economic or military dominance.

Figure 3.3 Ranking of Countries on the Reactive Scale

Figure 3.3 gives a suggested ranking of countries on the reactive scale, from strongly reactive to occasionally reactive.

Common linear-active behavior will facilitate smooth relations between, for instance, Swedes and Flemish Belgians. A common multi-active mentality will help contacts between Italians and Argentineans or Brazilians. In the Vietnam War, the most popular foreign troops with the South Vietnamese were reactive Koreans. There are naturally underlying similarities between members belonging to the same cultural category.

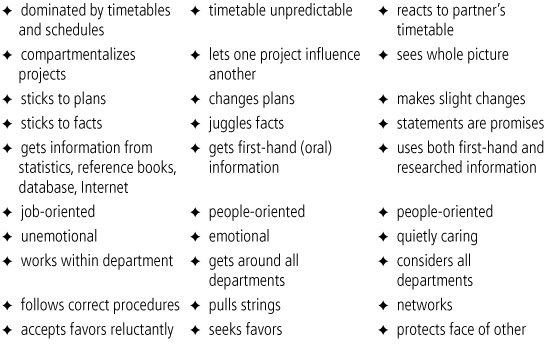

When members of different cultural categories begin to interact, the differences far outnumber the commonalities (see Figure 3.4).

Figures 3.5 to 3.7 illustrate intercategory relationships. When you look carefully at these diagrams, you can see that commonalities exist between all types, but tend to be thin on the ground between linear-actives and multi-actives. Reactives fit better with the other two, because they react rather than initiate. Consequently the trade-hungry Japanese settle comfortably in conservative, orderly Britain, but also have reasonably few problems adapting to excitable Latins on account of their similar views on people orientation, diplomatic communication and power distance.

Figure 3.4 Levels of Difficulty in LMR Interactions

Figure 3.5 Linear-Active/Multi-Active Horizons

Figure 3.6 Linear-Active/Reactive Horizons

Figure 3.7 Multi-Active/Reactive Horizons

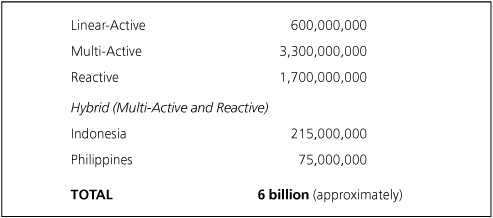

The entirely disparate worldviews of linear-active and multi-active people pose a problem of great magnitude in the early years of a new century of international trade and aspiring globalization. Can the pedantic, linear German and the voluble, exuberant Brazilian really share a “globalized” view of, for instance, duty, commitments or personnel policies? How do the French reconcile their sense of intellectual superiority with cold Swedish logic or American bottom-line successes? Will Anglo-Saxon hiring and firing procedures ever gain acceptability in people-orientated, multi-active Spain, Portugal or Argentina? When will product-oriented Americans, Britons and Germans come to the realization that products make their own way only in linear-active societies and that relationships pave the way for product penetration in multi-active cultures? One can well say, “Let’s concentrate on selling to the 600 million linear-active customers in the world,” but what about multi-active and reactive customers? The fact is, there are a lot of them: three and a half billion multi-active and just under two billion reactive at the last count. Figure 3.8 shows approximate numbers in each category for the year 2005.

Figure 3.8 Cultural Category Statistics for 2005

Figure 3.9 is a diagrammatic disposition of linear-active, multi-active and reactive variations among major cultures, based on decades-long observation and thousands of assessments of cultural profiles with respondents of 68 nationalities. The diagram, which is repeated in color on the back cover, is not drawn to scale as far as the cultural distance between each nationality is concerned. What it does indicate is the relative positioning of each culture in terms of its linear-active, multi-active or reactive nature. Thus the juxtaposition of Russia and Italy on the left side indicates they are linear-active/multi-active to a similar degree. It does not impute other cultural resemblances (core beliefs, religion, taboos, etc.). Spaniards and Arabs, though strikingly different in ideological and theological convictions, are able to benefit from their similar multi-active nature in communicating in an intensely personal and often compassionate manner. A Norwegian, though, is not on the same wavelength with either. As mentioned earlier, a senior multi-active Indian was able to combine his characteristics of warmth and people orientation to achieve success in managing the entire South American division of his company.

Figure 3.9 Cultural Types Model

I developed the LMR (linear/multi/reactive) method of testing so that individuals can determine their own cultural profiles. This classification or categorization of cultural groups is straightforward when compared with the somewhat diffuse instruments of the other cross-culturalists, and it has consequently proven comprehensible and user-friendly to students in hundreds of universities, schools of business and multinationals in industry, banking and commerce. It has also proven valuable to European government ministries that have the task of training personnel to interact on EU committees. As the assessment can be completed in 60–90 minutes on the Internet, it has enabled multinationals with staff scattered over several dozen countries to collect and collate profiles electronically. This gives them an insight as to which cultural areas of the world might prove appropriate for certain managers and employees. A senior British manager, for example, was determined to take over his company’s large Chinese market, but because he tested completely linear-active, the human resources department firmly steered him to a five-year stint in the Nordic division, where he excelled and made profits. In China he would have had to undergo a lengthy period of cultural adaptation.

In the majority of cases, the LMR Personal Cultural Profile assessment points the respondent toward a sympathetic relationship with a particular cultural group. A very linear person will find comfort in the orderliness and precision of Germans and Swiss. A multi-active, emotional person will not offend Italians or Latin Americans with his or her extroversion. A good listener, calm and nonconfrontational, will be appreciated and probably liked by the Japanese and Chinese.

Yet none of us is an island unto ourselves. Both personality and context will make us hybrid to some extent. Personal traits can occasionally contradict the national norm. A compassionate German may occasionally forsake his love of truth and directness in order to avoid giving offense. An introverted Finn may be subject to bursts of imagination. Some Americans may have a cautious streak.

As well as the personal or psychological traits of an individual, the context within which he or she operates is an important factor in fine-tuning categorization. Situational context is infinite in its variations, but three ingredients stand out: age, profession and field of study. Age is, of course, a well-recognized “layer of culture”—attitudes about society, authority, law and freedom are often generational. Younger people test strongly linear-active or multi-active according to their culture, but both groups become more reactive as they get older.

A person’s profession is also an influential factor. Linear-active people often wind up as engineers, accountants and technologists, and the exercise of their profession reinforces their linearity. Teachers, artists and sales and marketing staff lean toward multi-active options, where flexibility and feelings before facts fit their chosen type of work. Doctors and lawyers either need to be reactive by nature or develop reactive skills in order to listen carefully to their clients’ plights. Human resource managers tend to be more hybrid, as they seek and promote diversity in a firm’s human and cultural capital. Successful managers are also generally hybrid, with evenly balanced LMR scores. Skilled senior managers are usually more multi-active than the norm, especially in cultures where linearity is the norm.

Figure 3.10 The Fourth Dimension

Cultural profiles reveal many poor fits in people’s chosen careers. Accountants testing strongly as multi-active are often unhappy in their jobs. Linear scientists sent out to “sell” their company’s products have met with spectacular failures.

One’s field of study also influences his or her cultural profile. Assessments carried out with respondents in Western MBA degree programs show a high score for linearity, especially those from reactive cultures. Japanese students in such programs go for linear options that seem appropriate in the earnestly efficient MBA environment. Tested at home in Japan, however, their reactive score would be much higher.

Figure 3.11 Mindset Tug-of-War

Multi-actives are less “obedient” to Western-style MBA doctrines, but they will still test higher on the linear scale than they would in their home countries. Students of mathematics find it hard to ignore the linear options, and students of literature find that multi-active choices reflect more adequately the richness and poetic side of human nature. Those studying medicine, law or history have everything to gain by developing their own ability to react to suffering, legal predicaments and the enigma of history itself. Someone studying politics and championing human rights would be obliged to consider most multi-active solutions.

Such contextual considerations play an important role in fine-tuning cultural profiles. Yet they have limitations. One or two thousand years of cultural conditioning lend great momentum to an individual’s core beliefs and manner of expressing them. Ideally, cultural assessments like the Personal Cultural Profile should be carried out in one’s home environment, where natural reactions emerge from the ambience of close social bonds and where instinct prevails.

Let’s begin our discussion near the end of the multi-active point, where we encounter populations whose characteristics, though differing significantly in terms of historical background, religion and basic mindset, resemble each other considerably in the shape of outstanding traits, needs and aspirations (refer to Figure 3.9, page 42, throughout this section). For example, Latin Americans, Arabs, and Africans are multi-active in the extreme. They are excitable, emotional, very human, mostly nonaffluent and often suffer from previous economic exploitation or cultural larceny. Turkey and Iran, with more Eastern culture intact, are furthest from the multi-active point.

To switch our commentary to Northern European cultures, and proceeding along the linear-active/reactive axis, let’s consider three decidedly linear countries that exhibit reactive tendencies (when compared with the Germans and Swiss): Britain, Sweden and Finland. British individuals often seek agreement among colleagues (a reactive trait) before taking decisive action. Swedes are even further along the reactive line, seeking unanimity if possible. The Finns, however, are the most reactive of Europeans in that their firm decision-making stance is strongly offset by their soft, diffident, Asian communication style (plenty of silence) and their uncanny ability to listen at great length without interrupting.

The linear-active/multi-active axis is fairly straightforward. The United States, Norway and the Netherlands plan their lives along agenda-like lines. Australia has multi-active flashes due to substantial immigration from Italy, Greece and former Yugoslavia. Danes, though linear, are often referred to as the “Nordic Latins.” France is the most linear of the Latins, Italy and Spain the least. Russia, with its Slavic soul, classifies as a loquacious multi-active, but it slots in a little higher on the linear-active side on account of its many millions living in severely cold environments.

Belgium, India and Canada occupy median positions on their respective axes. These positions can be seen as positive and productive. Belgium runs a highly prosperous and democratic economy by maintaining a successful compromise between linear-active (Flemish) and multi-active (Walloon) administrations. Canada, because of massive immigration and intelligent government cultural care, is the most multicultural country in the world. Indians, though natural orators and communicators, have combined these natural skills and warmth with Eastern wisdom and courtesy. On top of that they have inherited a considerable number of British institutions, which enables them to relate to the West as well.

The early years of the twenty-first century find some degree of blending of cultural categories—in other words, movement along the linear-active/multiactive/reactive planes. Globalization, especially in business, has been one of the major forces behind this phenomenon. Nowhere is this trend more visible than along the linear-active/reactive plane. The successful Japanese, for instance, with their logical manufacturing processes and considerable financial acumen, are becoming more amenable to Western linear thinking. Hong Kong was created to make money, a very linear and countable commodity, while Lee Kuan Yew’s brilliant economic management of Singapore—the result of combining his innate Confucianism with his degree from Cambridge—pushed that tiny island city–state to the very borders of linear-activity, in spite of its 72 percent Chinese majority population.

Other East Asian reactive nations tend to temper their inherent reactivity by occasionally wandering along the reactive/multi-active plane. The Chinese are less interested in Western linear thinking and logic (“there is no absolute truth”) than in gut feelings and their periodic, highly emotional assertion of their inalienable rights and dominance based on a culture that is over 5,000 years old. They have no interest whatsoever in Western logic as applied to Tibet, Taiwan or human rights. Koreans, while extremely correct in their surface courtesy, actually suppress seething multi-active emotion, even tendencies toward violence, more than any other Asians. They frequently demonstrate explosive rage or unreliability vis-à-vis foreign partners or among themselves. Further along this plane, Indonesians and Filipinos, after many centuries of colonization, have developed into cultural hybrids, sometimes opposing, sometimes endorsing the policies and cultural styles of their former colonizers.

Individuals from certain nationalities sharing characteristics from two categories may find areas of cooperation or common conduct. Those close to the linear-active/reactive axis are likely to be strong, silent types who can work together calmly and tend to shun multi-active extroversion and loquacity. Those close to the multi-active/reactive axis will, in spite of visible differences, attach great importance to relationships and circumvent official channels by using personal contacts or networks. People close to the linear-active/multi-active axis, though opposites in many ways, are inevitably broad-minded on account of their range of traits and are likely to be forceful and persistent in their actions.

Individuals whose cultural profiles wander away from the axes and who occupy a central location inside the triangle may possess qualities that enable them to be efficient mediators or international team leaders.

Interaction among different peoples involves not only methods of communication but also the process of gathering information. This brings us to the question of dialogue-oriented and data-oriented cultures. In data-oriented cultures, one does research to produce lots of information that is then acted on. Swedes, Germans, Americans, Swiss and Northern Europeans in general love to gather solid information and move steadily forward from this database. The communications and information revolution is a dream come true for data-oriented cultures. It provides them quickly and efficiently with what dialogue-oriented cultures already know.

Which are the dialogue-orientated cultures? Examples are the Italians and other Latins, Arabs and Indians. These people see events and business possibilities “in context” because they already possess an enormous amount of information through their own personal information network (refer to Chapter 9, pages 141–175, for a complete explanation of “context”). Arabs and Portuguese will be well informed about the facts surrounding a deal since they will already have queried, discussed and gossiped in their circle of friends, business acquaintances and extensive family connections. The Japanese (basically listeners) may be even better informed, since the very nature of Japan’s “web” society involves them in an incredibly intricate information network operational during schooldays, college, university, Judo and karate clubs, student societies, developed intelligence systems and family and political connections.

People from dialogue-oriented cultures like the French and Spanish tend to get impatient when Americans or Swiss feed them with facts and figures that are accurate but, in their opinion, only a part of the big human picture. A French businessperson would consider that an American sales forecast in France is of little meaning unless there is time to develop the correct relationship with the customer on whom the success of the business depends. It is quite normal in dialogue-oriented cultures for managers to take customers and colleagues with them when they leave a job. They have developed their relationships.

There is a strong correlation between dialogue-oriented and multi-active people. Antonio (introduced earlier) does ten things at once and is therefore in continuous contact with humans. He obtains from these people an enormous amount of information—far more than Americans or Germans will gather by spending a large part of the day in a private office, door closed, looking at the computer screen.

Multi-active people are knee-deep in information. They know so much that the very brevity of an agenda makes it useless to them. At meetings they tend to ignore agendas or speak out of turn. How can you forecast a conversation? Discussion of one item could make another meaningless. How can you deal with feedback in advance? How can an agenda solve deadlock? Dialogue-oriented people wish to use their personal relations to solve the problem from the human angle. Once this is mentally achieved, then appointments, schedules, agendas, even meetings become superfluous.

If these remarks seem to indicate that dialogue-oriented people, relying on only word of mouth, suffer from serious disadvantages and drawbacks, it should be emphasized that it is very difficult to change from one system to the other. It is hard to imagine a Neapolitan company organizing its business along American lines with five-year rolling forecasts, quarterly reporting, six-month audits and twice-yearly performance appraisals. It is equally hard to imagine Germans introducing a new product in a strange country without first doing a market survey.

Most of the successful economies, with the striking exception of Japan, are in data-oriented cultures. Japan, although dialogue-oriented, also uses a large amount of printed information. Moreover, productivity also depends on other significant factors, particularly climate, so that information systems, while important, are not the whole story of efficiency and its logic. One might summarize by saying that a compromise between data-oriented and dialogue-oriented systems would probably lead to good results, but there are no clear examples of this having happened consistently in modern international business communities.

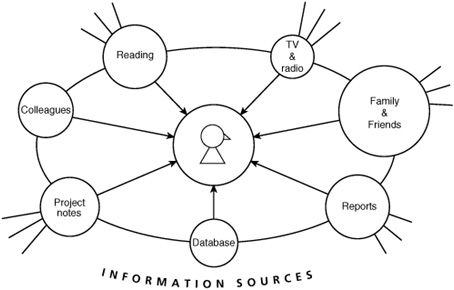

Figure 3.12 gives a suggested ranking for dialogue-oriented and data-oriented cultures. Figures 3.13, 3.14, and 3.15 illustrate the relatively few sources of information that data-oriented cultures draw on. The more developed the society, the more we tend to turn to printed sources and databases to obtain our facts. The information revolution has accentuated this trend and Germany, along with the United States, Britain and Scandinavia, is well to the fore. Yet printed information and databases are almost necessarily out of date (as anyone who has purchased mailing lists has found out to their cost). Last night’s whispers in a Madrid bar or café are hot off the press—Pedro was in Oslo last week and talked to Olav till two in the morning. Few data-oriented people will dig for information and then spread it in this way, although Germans do not fare badly once they get out of their cloistered offices. Northerners’ lack of gregariousness again proves a hindrance. By upbringing they are taught not to pry—inquisitiveness gains no points in their society—and gossip is even worse. What their database cannot tell them they try to find out through official channels: embassies, chambers of commerce, circulated information sheets, perhaps hints provided by friendly companies with experience in the country in question. In business, especially when negotiating, information is power. Sweden, Norway, Australia, New Zealand and several other data-oriented cultures will have to expand and intensify their intelligence-gathering networks in the future if they are to compete with information-hot France, Japan, Italy, Korea, Taiwan and Singapore. It may well be that the EU itself will develop into a hothouse exchange of business information to compete with the Japanese network.

Figure 3.12 Dialogue-Oriented, Data-Oriented Cultures

Figure 3.13 Information Sources: Data-Oriented Cultures

Figure 3.14 Information Sources: Dialogue-Oriented Cultures

Listening cultures, reactive in nature, combine deference to database and print information (Japan, Finland, Singapore and Taiwan are high tech) with a natural tendency to listen well and enter into sympathetic dialogue. Japanese and Chinese will entertain the prospect of very lengthy discourse in order to attain ultimate harmony. In this respect, they are as people oriented as the Latins. The Finns, inevitably more brief, nevertheless base their dialogue on careful consideration of the wishes of the other party. They rarely employ “steamrollering” tactics frequently observable in American, German and French debate. Monologues are unknown in Finland, unless practiced by the other party.

Figure 3.15 Information Sources: Listening Cultures (Japan)

Listening cultures believe they have the right attitude toward information gathering. They do not precipitate improvident action, they allow ideas to mature and they are ultimately accommodating in their decisions. The success of Japan and the four Asian tigers—South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore—as well as Finland’s prosperity, all bear witness to the resilience of the listening cultures.