Meetings can be interesting, boring, long, short, or unnecessary. Decisions, which are best made on the golf course, over dinner, in the sauna or in the corridor, rarely materialize at meetings called to make them. Protracted meetings are successful only if transportation, seating, room temperature, lunch, coffee breaks, dinner, theater outings, nightcaps and cable television facilities are properly organized.

There are more meetings than there used to be. Businesspeople can now go to a meeting in another continent and often leave for home the same day. Videoconferencing is already reducing business travel, but this, too, is a type of meeting.

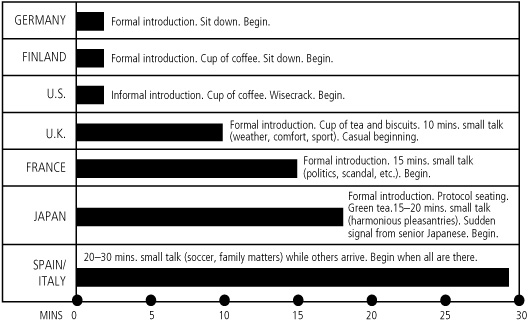

For the moment, however, consider how people conduct meetings, face-to-face, in different countries. Meetings are not begun in the same way as we move from culture to culture. Some are opened punctually, briskly and in a “businesslike” fashion. Others start with chitchat, and some meetings have difficulty getting going at all. Figure 10.1 gives some examples of different kinds of starts in a selection of countries.

Germans, Scandinavians and Americans like to get on with it. They see no point in delay. Americans are well known for their business breakfasts (a barbaric custom in Spanish eyes). In England, France, Italy and Spain it would be considered rude to broach serious issues immediately; it’s much more civilized to ease into the subject after exchanging pleasantries for 10 minutes—or half an hour. The English, particularly, are almost shame-faced at indicating when one should start: “Well, Charlie, I suppose we ought to have a look at this bunch of paperwork.” In Japan, where platitudes are mandatory, there is almost a fixed period that has to elapse before the senior person present says: “Jitsu wa ne…” (“The fact of the matter is…”), at which point everybody gets down to work.

Figure 10.1 Beginning a Meeting

Just as ways of beginning a meeting vary, so do methods of structuring them. Linear-active people are fond of strict agendas, for agendas have linear shape. Other, more imaginative minds (usually Latins) tend to wander, wishing to revisit or embellish, at will, points already discussed. Their agenda, if one can call it that, might be described as roundabout, or circuitous, which for Germans and Americans means no real agenda at all. Asians, especially Japanese, have another approach again, one that concentrates on harmonizing general principles prior to examining any details. At meetings where two or more cultural groups are involved, or at any meeting of an international team, the chairperson has the task of establishing a procedural and communicative style that will be acceptable to, even welcomed by, all the participants.

The purpose of a meeting depends on where one is coming from. Britons and Americans see a meeting as an opportunity to make decisions and get things done. The French see it as a forum where a briefing can be delivered to cover all aspects of a problem. They hunger for elegant processes. Germans, more concerned with precision and exactness, expect to gain compliance. Italians use meetings to evaluate support for their plans. The Japanese regard the first few sessions as occasions for establishing status and trust and finding out what possible sources of discord need to be eliminated from the outset. All of these objectives may be seen as worthy by everyone, but the priorities will vary. A skillful chairperson must be sensitive to these expectations and be quick to define a mutually shared aim.

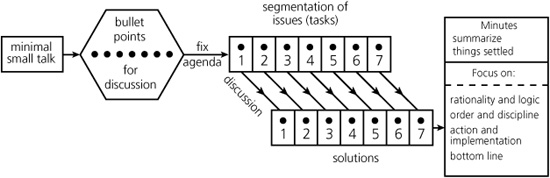

My recent experience with a oneworld international team (British, American, Australian, Irish, Spanish, Chilean, Finnish and Chinese airlines alliance) indicated that skillful team leaders—in this case a Canadian, followed by a Finn—are able to blend procedural styles to mutual satisfaction among their colleagues. Contrasting requirements were addressed openly; certain wishes were analyzed and accommodated. The team leaders recognized that the linear-active, multiactive and reactive procedural styles each possessed unique strengths that could be combined to produce a successful oneworld style. Tolerance and a sense of humor on the part of the team leaders were also significant contributory factors. Figures 10.2, 10.3 and 10.4 reflect the different preferences of the linear-active, multi-active and reactive team members.

Linear-active members need relatively little preamble or small talk before getting down to business. They like to introduce bullet points that can serve as an agenda. Tasks or issues are segmented, discussed and dealt with one after the other. Solutions reached are summarized in the minutes.

Figure 10.2 Structuring a Meeting—Linear-Active

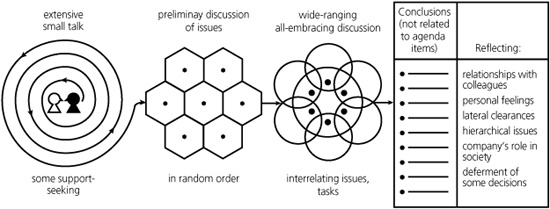

Figure 10.3 Structuring a Meeting—Multi-Active

Figure 10.4 Structuring a Meeting—Reactive

Multi-active members are not happy with the bullet-point approach, which they see as premature conclusions reached by their linear colleagues. They prefer to take points in random order (or in order of importance) and discuss them for hours before listing bullet points as conclusions. When they see topics listed at the beginning, they feel they have been manipulated.

Reactive people do not have the linear obsession with agendas, neither are they wooed by multi-active arguments. In Japanese eyes, for instance, things are not black and white, possible or impossible, right or wrong. They see arguments and ideas as points converging and ultimately merging. An emotional coming together is considered more important than an intellectual approach.

There are no universal rules for holding meetings. In addition to the different viewpoints regarding the structure of the proceedings, the nonverbal dimension and the physical comportment of participants is of utmost importance and varies to a great degree.

While verbal discussion might occupy 80–90 percent of the time devoted to a negotiation, psychologists tell us that the “message” conveyed by our actual words may be 20 percent or even less. Where, then, is the message?

The venue of the meeting itself may have positive or negative implications. Are we home or away? Are we seated comfortably? French negotiators, for example, are said to arrange lower seats for their opponents! Hierarchy of seating is also important. Dress, formal and informal, correct and inappropriate, can also give negotiators false impressions of the seriousness or casualness of the other side. The deliberate use of silence can be an invaluable advantage in negotiations, especially against Americans, who cannot stand more than a few seconds of silence. In Finland and Japan, for instance, silence is not uncomfortable but is an integral part of social interaction. In both countries what is not said is regarded as important. Listening habits can also play an important part in the negotiating process. Finns and Japanese again excel in their ability to listen closely for long periods of time,

Protocol is important in France, Germany, Japan and some other countries, whereas it is minimized in the Netherlands, Australia, Canada, the Nordic countries and in the United States.

Linear-actives enhance their rational, factual approach with a calm demeanor, little show of emotion or sentiment, and restricted body language. Reactives behave likewise; impassivity is a frequent description of their composure. Multi-actives, on the other hand—the French, Hispanics, Italians, Greeks, Southern Slavs, Arabs and Africans in particular—are often uninhibited in expressing their views with vigorous gesticulation and dramatic change of facial expression.

This striking variance in physical behavior, which results in linear-actives and reactives perceiving multi-active people as excitable, overly emotional and possibly unreliable and neurotic, can have such a profound effect on the process and outcome of meetings that it deserves some commentary and analysis here before we go on to the subject of negotiating and decision making.

Body language, including facial expressions and loudness of voice or manner, gestures, degree of eye contact and so on, may play an enormous role in the success—or failure—of a meeting. Members of a Spanish delegation may argue fiercely with each other while opponents are present, causing the Japanese to think they are fighting. Asians are bemused when the same “quarreling Spaniards” pat each other like lifelong friends a few moments later. Smiles, while signifying good progress when on the faces of Britons, Scandinavians and Germans, might mean embarrassment or anger when adopted by Chinese and often appear insincere in the features of beaming Americans. Finns and Japanese often look doleful when perfectly happy, whereas gloom on an Arab face indicates true despondency. The frequent bowing of the Japanese is seen as ingratiating by Americans, while the hearty nose-blowing of Westerners in public is abhorred by the Japanese, who invariably leave the room to do this.

Anthropologists assume that speech developed to make body language more explicit, and that as the former became more sophisticated, gestures became less necessary. It is not that simple. In spite of the incredible sophistication, subtlety and flexibility of speech, it seems that some human groups still rely basically on body language to convey what they really mean, especially where intense feelings are concerned. Such people are the Italians, Greeks, South Americans and most other Latins, as well as many Africans and people from the Middle East. Others, such as Japanese, Chinese, Finns and Scandinavians, have virtually eliminated overt body language from their communication.

People from reactive and linear-active cultures are generally uncomfortable when their “space bubble” is invaded by excitable multi-actives. They regard the space within 1.2 meters of their body as inviolable territory for strangers, with a smaller bubble of 0.5 meters for close friends and relatives.

When a multi-active Mexican positions himself 0.5 meters away from an Englishman, he is ready to talk business. The Englishman sees him in English personal space and backs off to a more comfortable distance. In doing so, he relegates the Mexican to the South American “public zone” (1.2 meters) and the latter thinks the Englishman finds his physical presence distasteful or does not want to talk business. For a Mexican to talk business over a yawning chasm of 1.2 meters is like an English person shouting out confidential figures to someone at the other end of the room.

Finns and Japanese do not seem to have any body language. I say do not seem because in fact both cultural groups do use body language that is well understood by fellow nationals in each country. In both societies the control and disciplined management of emotions leads to the creation of a restrained type of body language that is so subtle that it goes unnoticed by the foreign eye. Because Finns and Japanese are accustomed to looking for minimal signs, the blatantly demonstrative body language of multi-active Italians, Arabs and South Americans is very disconcerting for them (cultural shock). It is as if someone used to listening to the subtle melodies of Chopin or Mozart were suddenly thrown into a modern disco. The danger is, of course, that overreaction sets in—a judgmental reaction to the multi-active’s expressive body language. Japanese consider Americans and Germans as charging bulls; Finns see the French as too clever, Italians as overemotional and even Danes as a bit slick.

Because the body language of multi-actives can cause such shock to those not used to it, let’s discuss it before going on.

Eyes are among the more expressive parts of the body. In multi-active cultures, speakers will maintain close eye contact while they deliver their message. This is particularly noticeable in Spain, Greece and Arab countries. Such close eye contact (some linear-actives and reactives would call it staring) implies dominance and reinforces one’s position and message. In Japan this is considered improper and rude. Japanese avoid eye contact 90 percent of the time, looking at a speaker’s neck while listening and at their own feet or knees when they speak themselves.

In societies where hierarchy is important, it is easy to detect the “pecking order” by observing people’s eye behavior. Lower-ranking staff often look at superiors, who ignore them unless they are in direct conversation with them. When anyone cracks a joke or says something controversial, all the subordinates’ eyes will switch immediately to the chief personage to assess his or her reaction. This is less evident in northern countries where head and eye switching would be much more restrained.

French and Hispanic people indulge in the nose twitch, snort or sniff to express alertness, disapproval or disdain respectively. The Portuguese tug their earlobes to indicate tasty food, though this gesture has sexual connotations in Italy. In Spain the same action means someone is not paying for his drinks, and in Malta it signifies an informer. It is best to recognize these signs, but not embark on the risky venture of attempting to imitate them.

It is said that the mouth is one of the busiest parts of the human body, except in Finland where it is hardly used (except for eating and drinking). This is, of course, not strictly true, but most societies convey a variety of expressive moods by the way they cast their lips. Charles De Gaulle, Saddam Hussein and Marilyn Monroe made their mouths work overtime to reinforce their message or appeal. The tight-lipped Finn shrinks away from such communicative indulgences as the mouth shrug (French), the pout (Italian), the broad and trust-inviting smile (American) or even the fixed polite smile of the Asian. Kissing one’s fingertips to indicate praise (Latin) or blowing at one’s finger-tip (Saudi Arabian) to request silence are gestures alien to the Nordic and Asian cultures.

Multi-active cultural groups, far more than others, also use all the rest of their bodies to express themselves. For example, they have very mobile shoulders, normally kept still in northern societies. The Gallic shoulder shrug is well known from our observations of Maurice Chevalier, Jean Gabin and Yves Montand. Latins keep their shoulders back and down when tranquil and observant but push them up and forward when alarmed, anxious or hostile.

Arms, which are used little by Nordics during conversation, are an indispensable element in one’s communicative weaponry in Italy, Spain and South America. Frequent gesticulating with the arms is one of the features Northern Europeans find hardest to tolerate or imitate, being associated with insincerity, overdramatization and therefore unreliability. As far as touching is concerned, however, the arm is the most neutral of body zones; even English will take guests by the elbow to guide them through doorways or indulge in the occasional arm pat to deserving subordinates or approaching friends.

The hands are among the most expressive parts of the body. Immanuel Kant called them “the visible parts of the brain.” Italians watching Finnish hands may be forgiven for thinking that Finns have sluggish brains. It is undeniable that Northern peoples use their hands less expressively than Latins or Arabs, who recognize them as a brilliant piece of biological engineering. There are so many signals given by the use of the hands that we cannot even begin to name them all here. There are entire books written on hand gestures. I offer only a couple of examples here: “thumbs up,” used in many cultures but so ubiquitous among Brazilians that they drive you mad with it; the hands clasped behind one’s back to emphasize a superior standing (e.g., Prince Philip and various other royalty as well as company presidents); and the akimbo posture (hands on hips), which denotes rejection or defiance, especially in Mediterranean cultures.

As we move even further down the body, less evident but equally significant factors come into play. Even Northern Europeans participate in “leg language like everybody else. As no speech is required, it inflicts no strain on them.” In general the “legs together” position signifies basically defensiveness against a background of formality, politeness or subordination. Most people sit with their legs together when applying for a job; it indicates correctness of attitude. This position is quite common for Anglo-Saxons at first meetings, but they usually change to “legs crossed” as discussions become more informal. The formal Germans and Japanese can go through several meetings maintaining the legs-together position. There are at least half a dozen different ways of crossing your legs; the most formal is the crossing of ankles only, the average is crossing the knees, and the most relaxed and informal is the “ankle-on-knee” cross so common in North America.

When it comes to walking, the English and Nordics walk in a fairly neutral manner, avoiding the Latin bounce, the American swagger and the German march. It is more of a brisk plod, especially brisk in winter, when the Spanish dawdle would lead to possible frostbite.

It is said that the feet are the most honest part of the body: we are so self-conscious about our speech or eye and hand movements that we actually forget what our feet are doing most of the time. The honest Nordics, therefore, send out as many signals with their feet as the Latins do. Foot messages include tapping on the floor (boredom), flapping up and down (want to escape), heel lifting (desperate to escape) and multi-kicking from a knees-crossed position (desire to kick the other speaker). Nordic reticence sometimes reduces the kicking action to wiggling of the toes up and down inside shoes, but the desire is the same. Foot stamping in anger is common in Italy and other Latin countries, but virtually unused north of Paris.

Some forms of sales training actually include a close study of body language, especially in those societies where it is demonstrative. Italian salespeople, for instance, are told to pay great attention to the way their clients sit during a meeting. If they are leaning forward on the edge of their chairs, they are interested in the discussion or proposal. If they sit back in their chairs, they are either bored or confident that things will turn their way if they are patient. Buttoned jackets and arms or legs tightly crossed betray defensiveness and withdrawal. A savvy Italian salesperson will not try to close a sale in such a situation. Neither should a proposal be made to someone who is tapping with feet or fingers—they should be asked to speak. Italian salespeople are also taught to sit as close as they can to their customers when attempting to close the deal. Latin people will tend to buy more from a person sitting close to them than from someone at a distance.

Negotiations are the heart of many, perhaps most, meetings. Western business schools, management gurus, trade consultants and industrial psychologists focused, for most of the twentieth century, on the goal of reducing the process of negotiation to a fine art, if not a science.

One could be forgiven for assuming that relatively unchanging, universally accepted principles of negotiation would by now have been established—that an international consensus would have been reached on how negotiators should conduct themselves in meetings, how the phases of negotiation should proceed and how hierarchies of goals and objectives should be dealt with. One might assume that negotiators—with their common concepts (learned from manuals) of ploys, bargaining strategies, fallback positions, closing techniques and mix of factual, intuitive and psychological approaches—are interchangeable players in a serious game where internationally recognized rules of principles and tactics lead to a civilized agreement on the division of the spoils. This “game plan” and its outcome are not unusual in domestic negotiation between nationals of one culture.

But the moment people of different cultures are involved, the approach of each side will be defined or influenced by cultural characteristics. In fact, one could say nationals of different cultures negotiate in completely different ways. In Part Three I set out in some detail the negotiation styles of the major countries. The following pages give an overview of the cross-cultural factors that are likely to have a bearing on the negotiation process, but first, a few examples of cultural differences.

Germans will ask you all the difficult questions from the start. You must convince them of your efficiency, quality of goods and promptness of service. These are features Germans consider among their own strong cards and they expect the same from you, at the lowest possible price. They will give you little business at first but will give you much more later when they have tested you—and if you prove trustworthy and your product of good quality. The French tend to move much faster, but they may also withdraw their business more quickly. Spaniards often seem not to appreciate the preparations you have made to facilitate a deal. They do not study all the details of your proposal or play, but they do study you. They will only do business with you if they like you and think you are honorable.

The Japanese are similar in this respect. They must like you and trust you, otherwise there is no deal. Like the Germans, they will ask many questions about price, delivery and quality, but the Japanese will ask them all ten times. You have to be patient. The Japanese are not interested in profits immediately, only in the market share and reputation of the company.

Finns and Swedes expect modernity, efficiency and new ideas. They like to think of themselves as being up to date and sophisticated. They will expect your company to have the latest office computers and streamlined factories. The American business approach is to get down quickly to a discussion of investment, budgets and profits. They hurry you along and make you sign the five-year plan.

Businesspeople from small nations with a long tradition of trading, such as the Netherlands and Portugal, are usually friendly and adaptable, but prove to be excellent negotiators. Brazilians never believe your first price to be the real one and expect you to come down later, so you must take this into your calculations.

Two problems arise almost immediately: professionalism of the negotiating team and cross-cultural bias.

As far as professionalism is concerned, what is often forgotten is that negotiating teams rarely consist of professional or trained negotiators. While this does not apply so much to government negotiation, it is often readily observable with companies. A small company, when establishing contact with a foreign partner, is often represented by its managing director and an assistant. A medium-sized firm will probably involve its export director, finance director and necessary technical support. Even large companies rely on the performance of the managing director supported by, perhaps, highly specialized technical and finance staff who have no experience whatsoever in negotiating. Engineers, accountants and managers used to directing their own nationals are usually completely lacking in foreign experience. When confronted with a different mindset, they are not equipped to figure out the logic, intent and ethical stance of the other side and may waste time talking past each other. This leads us to cross-cultural bias.

When we find ourselves seated opposite well-dressed individuals politely listening to our remarks, their pens poised over notepads similar to ours, their briefcases and calculators bearing the familiar brand names, we often assume that they see what we see, hear what we say and understand our intent and motives. In all likelihood they start with the same innocent assumptions, for they, too, have not yet penetrated our cosmopolitan veneer. But the two sets of minds are working in different ways, in different languages regulated by different norms and certainly envisaging different objectives. It is here with objectives that we begin our discussion.

Even before the meeting begins, the divergence of outlooks is exerting decisive influence on the negotiation to come. If we take three cultural groups as an example—American, Japanese and Latin-American—the hierarchy of negotiating objectives are likely to be as in Figure 10.5.

Figure 10.5 Negotiating Objectives

Americans are deal-oriented; they see it as a present opportunity that must be seized. American prosperity was built on opportunities quickly taken, and immediate profit is seen as the paramount reality. Today, shareholders’ expectation of dividends creates rolling forecasts that put pressure on U.S. executives to make the deal now in order to meet their quarterly figures. For the Japanese, the current project or proposal is a trivial item in comparison with the momentous decision they have to make about whether or not to enter into a lasting business relationship with the foreigners. Can they harmonize the objectives and action style of the other company with the well-established operational principles of their own kaisha (company)? Is this the right direction for their company to be heading in? Can they see the way forward to a steadily increasing market share? The Latin Americans, particularly if they are from a country such as Mexico or Argentina (where memories of U.S. exploitation and interference are a contextual background to discussion), are anxious to establish notions of equality of standing and respect for their team’s national characteristics before getting down to the business of making money. Like the Japanese, they seek a long-term relationship, although they will inject into this a greater personal input than their group-thinking Eastern counterparts.

This master programming supplied by our culture not only prioritizes our concerns in different ways, but makes it difficult for us to “see” the priorities or intention pattern of others. Stereotyping is one of the flaws in our master program, often leading us to false assumptions. Here are three examples:

![]() French refusal to compromise indicates obstinacy.

French refusal to compromise indicates obstinacy.

(Reality: The French see no reason to compromise if their logic stands undefeated.)

![]() Japanese negotiators cannot make decisions.

Japanese negotiators cannot make decisions.

(Reality: The decision was already made before the meeting, by consensus. The Japanese see meetings as an occasion for presenting decisions, not changing them.)

![]() Mexican senior negotiators are too “personal” in conducting negotiations.

Mexican senior negotiators are too “personal” in conducting negotiations.

(Reality: Their personal position reflects their level of authority within the power structure back home.)

The French, Spaniards, most Latin Americans and the Japanese regard a negotiation as a social ceremony to which important considerations of venue, participants, hospitality and protocol, timescale, courtesy of discussion and the ultimate significance of the session are attached. Americans, Australians, Britons and Scandinavians have a much more pragmatic view and are less concerned about the social aspects of business meetings. The Germans and Swiss are somewhere in between.

U.S. executives generally want to get the session over with as quickly as possible, with entertaining and protocol kept to a minimum. Mutual profit is the object of the exercise, and Americans send technically competent people to drive the deal through. They persuade with facts and figures and expect some give-and-take, horse-trading when necessary. They will be argumentative to the point of rudeness in a deadlock and regard confrontation and in-fighting as conducive to progress. No social egos are on the line: if they win, they win; if they lose, what the hell, too bad.

Senior Mexican negotiators cannot afford to lose to Americans, least of all to technicians. Their social position is on the line. They do not enter into a negotiation to swap marbles with engineers and accountants. Their Spanish heritage causes them to view the meeting as a social occasion where everybody is to show great respect for the dignity of the others; discuss grand outlines as opposed to petty details; speak at length in an unhurried, eloquent manner; and show sincerity of intent while maintaining a modicum of discretion to retain some privacy of view.

The Japanese view the session as an occasion to ratify ceremonially decisions that have previously been reached by consensus. They are uncomfortable with both Mexican rhetoric and American argumentativeness, although they are closer to the Latins in their acceptance of protocol, lavish entertainment and preservation of dignity. As befits a social occasion, the Japanese will be led by a senior executive who sets standards of courtesy and deference. He may have no technical competence, but he represents the weighty consensus that backs his authority.

The French view the setting of the negotiation as a social occasion and a forum for their own cleverness. Their sense of history primes them for the traditional French role of international mediator. Their leader will be their best speaker, usually highly educated and self-assured. It will require a skillful American, Briton or Japanese to best him or her in debate. The leader will be unimpressed by American aggressive ploys. French Cartesian logic will reduce the “muddling-through” English and “belly-talking” Japanese to temporary incoherence. This is not a session for give and take, but for presenting well-formulated solutions. Lavish French hospitality will compensate for sitting through lengthy speeches.

Scandinavians, while relatively at home with Americans and Anglo-Saxons and familiar enough with German bluntness and protocol, have little feel for the social nuances displayed by Latins and the Japanese. In their straightforward egalitarian cultures, business meetings are conducted without regard to social status. Who the other negotiators are, their class, their connections, who they are related to—all these things are irrelevant to Finns and Swedes. Although more polite than Americans, Scandinavians have difficulty in settling down to a role in meetings where social competence dominates technical know-how.

We see, therefore, how diverse cultures view the negotiating process in a different light, with dissimilar expectations about its conduct and outcome. Once the talks begin, the values, phobias and rituals of the particular cultural groups soon make themselves evident. The Americans rely on statistical data and personal drive to compress as much action and decision making as possible into the hours available. The Dutch, Finns and Swiss, although somewhat less headlong, will be similarly concerned with the time/efficiency equation. The Germans will place emphasis on thoroughness, punctuality and meeting deadlines. For this they require full information and context and, unlike Latins, will leave nothing “up in the air.”

The French give pride of place to logic and rational argument. The aesthetics of the discussion are also important to them, and this will be reflected in their dress sense, choice of venue, imaginative debating style and preoccupation with proper form. The Japanese have their own aesthetic norms, also requiring proper form, which in their case is bound up with a complex set of obligations (vertical, horizontal and circular!). In discussion they value the creation of harmony and quiet “groupthink” above all else. The British also give priority to quiet, reasonable, diplomatic discussion. Their preoccupation with “fair play” often comes to the fore and they like to see this as a yardstick for decision making. Latins, as we have learned, place emphasis on personal relationships, honorable confidences and the development of trust between the parties. This is a slow process and they require an unhurried tempo to enable them to get to know their counterparts. This is well understood by the Japanese, but conflicts with the American desire for quick progress.

Self-image is part and parcel of value perception, and negotiators see themselves in a light that may never reach their foreign counterpart, although their playing of that role may irritate other nationalities. The English often assume a condescending and arbitrary role, a carryover from the days when they settled disputes among the subjects of Her Majesty’s Empire. They may still see themselves as judges of situations that can be controlled with calm firmness and funny stories. The French have an equally strong sense of history and consider themselves the principal propagators of Western European culture. This encourages them to take a central role in most discussions, and they tend to “hold the floor” longer than their counterparts would wish.

Because Latin Americans see themselves as exploited by the United States, they often display heightened defensive sensitivity, which may frequently delay progress. They consider themselves culturally superior to North Americans and resent the latter’s position of power and dominance.

The Japanese, on the other hand, are comfortable with American power. As victors in the Second World War, the U.S. earned the number one spot. Inequality is basic in both Japanese and Chinese philosophies, and the former are quite satisfied with the number two spot—for the time being. The Japanese see themselves as farsighted negotiators and courteous conversationalists. They have no aspirations to dominate discussion any more than they have to become world or even Asian leaders. They are privately convinced, however, of their uniqueness, of which one facet is intellectual superiority. Unlike the French, they base this belief not on intellectual verbal prowess, but on the power of strong intuition.

It is not uncommon for negotiations to enter a difficult stage where the teams get bogged down or even find themselves in a deadlock. When such situations occur between nationals of one culture, there is usually a well-tried mechanism—changing negotiators or venue, adjourning the session, or “repackaging” the deal—that constitutes an escape route whereby momentum can be regained without loss of face for either side. Arab teams will take a recess for prayer and come back with a more conciliatory stance; Japanese delegations will bring in senior executives to “see what the problem is”; Swedish opponents will go out drinking together; Finns will retire to the sauna.

Mutually agreeable mechanisms are not always available in international negotiations, however. The mechanism for breaking a deadlock that is used by Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians is usually that of compromise. Other cultures, however, do not see compromise in the same favorable light and remain unconvinced of its merit. In French eyes, give-and-take is Anglo-speak for wheel-and-deal, which they see as an inelegant, crude tactic for chiseling away at the legitimate edifice of reason they have so painstakingly constructed. Yes, let’s all be reasonable, they say, but what is irrational in what we have already said?

For the Japanese, compromise during a negotiation is a departure from the company-backed consensus, and woe betide the Japanese negotiators who concede points without authority. Adjournment is sometimes the only way out. Many a senior Tokyo-based executive has been awakened in the middle of the night by trans-Pacific telephone calls asking for directives. Delays are, of course, inevitable.

Among the Latins, attitudes toward compromise vary. The Italians, although they respect logic almost as much as the French, know that our world is indeed irrational and pride themselves on their flexibility. The Spaniards and South Americans see compromise as a threat to their pundonor (dignity), and several nations, including Argentina, Mexico and Panama, display obstinacy in conceding anything to “insensitive, arrogant Americans.”

Compromise may be defined as finding a middle course and, to this end, both the Japanese and Chinese make good use of “go-betweens.” This is less acceptable to Westerners, who prefer more direct contact (even confrontation) to seek clarity. Confrontation is anathema to Asians and most Latins and disliked by Brits and Swedes. Only Germans, Finns, Americans and Australians might rank directness, bluntness and honesty above subtle diplomacy in business discussions. Arabs also like to use go-betweens. The repeated offer of King Hussein of Jordan to mediate in the dispute between Saddam Hussein and George Bush (Senior) unfortunately fell on deaf ears, even though, as a thoroughly Westernized Arab (with British and American wives to boot) he was the ideal middleman for that particular cross-cultural situation.

The problem remains that intelligent, meaningful compromise is only possible when one is able to see how the other side prioritizes its goals and views the related concepts of dignity, conciliation and reasonableness. These are culturally relative concepts and therefore emotion-bound and prickly. However, an understanding of such concepts and an effort to accommodate them form the unfailing means of unblocking the impasse. Such moves are less difficult to make than one might believe. They do, however, require knowledge and understanding of the traditions, cultural characteristics and ways of thinking of the other side. What, for example, is logical and illogical?

French debating logic is Cartesian in its essence, which means that all presuppositions and traditional opinions must be cast aside from the outset, as they are possibly untrustworthy. Discussion must be based on one or two indubitable truths upon which one can build, through mechanical and deductive processes, one’s hypotheses. Descartes decreed that all problems should be divided into as many parts as possible and the review should be so complete that nothing could be omitted or forgotten. Given these instructions and doctrine, it is hardly surprising that French negotiators appear complacently confident and long-winded. They have a hypothesis to build and are not in a hurry.

Opponents may indeed doubt some of the French “indubitable truths” and ask who is qualified to establish the initial premises. Descartes has an answer to this: rational intellect is not rare; it can be found in anyone who has been given help in clear thinking (French education) and is free from prejudice. What is more, conclusions reached through Cartesian logic “compel assent by their own natural clarity.” There, in essence, is the basis for French self-assurance and an unwillingness to compromise.

The fellow French would certainly meet thrust with counter-thrust, attempting to defeat the other side’s logic. Many cultures feel little inclined to do this. The Japanese—easy meat to corner with logic—have no stomach for the French style of arguing or public demonstrations of cleverness.

Anglo-Saxons, particularly Americans, show a preference for Hegelian precepts. According to Hegel, people who first present diametrically opposed points of view ultimately agree to accept a new and broader view that does justice to the substance of each. The thesis and antithesis come together to form a synthesis (now we’re back to compromise). The essence of this doctrine is activity and movement, on which Americans thrive. An American negotiator is always happy to be the catalyst, ever willing to make the first move to initiate action.

Chinese logic is different again, founded as it is on Confucian philosophy. The Chinese consider the French search for truth less important than the search for virtue. To do what is right is better than to do what is logical. They also may show disdain for Western insistence that something is black or white, that opposite courses of action must be right or wrong. Chinese consider both courses may be right if they are both virtuous. Confucianism decrees moderation in all things (including opinion and argument); therefore, behavior toward others must be virtuous. Politeness must be observed and others must be protected from loss of face. Taoist teaching encourages the Chinese to show generosity of spirit in their utterances. The strong are supposed to protect the weak, so the Chinese negotiator will expect you not to take advantage of your superior knowledge or financial strength!

Unless they are using interpreters, negotiators need a common language. English is now the language of diplomacy as well as international trade, but beware. English can be a communication link, or it can be a barrier. When Americans use in discussion terms like democratic, fair, reasonable, level playing field, evidence, common sense, equitable or makes business sense, they often fail to realize that the Japanese interpret these words and expressions in a different light and that most Latins will instinctively distrust each and every one of them. Democracy has a different meaning in every country. American evidence is statistical; in many other cultures it is emotional. In Russia the expression makes business sense has virtually no meaning. Language is a poor communication tool unless each word or phrase is seen in its original cultural context. This is naturally true of other languages as well. Words such as Weltschmerz (German), sisu (Finnish) and saudades (Portuguese) mean little to people from other cultures even when translated, and no Westerner could possibly appreciate the web of duties and obligations implied by the Japanese words giri and on.

Negotiations lead to decisions. How these are made, how long they take to be made and how final they are once made are all factors that will depend on the cultural groups involved.

Americans love making decisions because they usually lead to action and Americans are primarily action oriented. The French love talking about decisions, which may or may not be made in the future. If their reasoned arguments do not produce what in their eyes is a logical solution, then they will delay decisions for days or weeks if necessary.

The Japanese hate making decisions and prefer to let decisions be made for them by gradually building up a weighty consensus. In their case, a decision may take months. This exasperates Americans and many Northern Europeans, but the Japanese insist that big decisions take time. They see American negotiators as technicians making a series of small decisions to expedite one (perhaps relatively unimportant) deal. Once the Japanese have made their decisions, however, they expect their American partner to move like lightning toward implementation. This leads to further exasperation.

What Westerners fail to understand is that the Japanese, during the long, painstaking process of building a consensus for a decision, are simultaneously making preparations for the implementation of the project or deal. The famous ringi-sho system of Japanese decision making is one of the most democratic procedures of an otherwise autocratic structure. In many Western countries action is usually initiated at the top. In Japan, younger or lower-ranking people often propose ideas that are developed by middle management and ultimately shown to the president. There is a long, slow process during which many meetings are held to digest the new idea and at length a draft will be made to be passed around for all to see. Each person is invited to attach his or her seal of approval so that unanimity of agreement is already assumed before the president confirms it. He will not do this lightly since he, not middle management, will have to resign if there is a catastrophe. To ask a Japanese negotiator during a meeting to take “another direction” is quite unacceptable. No hunches or sudden turnabouts here. Drastic swings of intent would force the Japanese team to go right back to the drawing board.

Mediterranean and Latin American teams look to their leader to make decisions and do not question his or her personal authority. The leader’s decision making, however, will not be as impromptu or arbitrary as it seems. Latins, like the Japanese, tend to bring a cemented-in position to the negotiating table, which is that of the power structure back home. This contrasts strongly with the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian willingness to modify stances continuously during the talk if new openings are perceived.

French negotiators seldom reach a decision on the first day. Many a British negotiator has asked (in vain) French colleagues at 4:00 P.M., “Well, can we summarize what we have agreed so far?” The French dislike such interim summaries, since every item on the agenda may be affected by later discussion. Only at the end can everything fit into the “Grand Design.” Short-term decisions are seen as of little consequence.

Once a decision has been made, the question then arises as to how final or binding it is. Anglo-Saxons and Germans see a decision, once it has been entered into the minutes of a meeting, as an oral contract that will shortly be formalized in a written, legal document. Ethically, one sticks to one’s decisions. Agenda items that have been agreed on are not to be resurrected or discussed again.

Neither Japanese nor Southern Europeans see anything wrong, ethically, in going back to items previously agreed on. “Chop and change” (anathema to Anglo-Saxons) holds no terrors for many cultures.

The French show lack of respect for adherence to agenda points or early mini-decisions. This is due not so much to their concern about changing circumstances as to the possibility (even likelihood) that, as the discussions progress, Latin imagination will spawn clever new ideas, uncover new avenues of approach, improve and embellish accords that later may seem naïve or rudimentary. For them a negotiation is often a brainstorming exercise. Brainwaves must be accommodated! Italians, Spanish, Portuguese and South Americans all share this attitude.

Different ethical approaches or standards reveal themselves in the way diverse cultures view written contracts. Americans, British, Germans, Swiss and Finns are among those who regard a written agreement as something that, if not holy, is certainly final.

For the Japanese, on the other hand, the contract they were uncomfortable in signing anyway is merely a statement of intent. They will adhere to it as best they can but will not feel bound by it if market conditions suddenly change, if anything in it contradicts common sense, or if they feel cheated or legally trapped by it. New tax laws, currency devaluations or drastic political changes can make previous accords meaningless. If the small print turns out to be rather nasty, they will ignore or contravene it without qualms of conscience. Many problems arise between Japanese and U.S. firms on account of this attitude. The Americans love detailed written agreements that protect them against all contingencies with legal redress. They have 300,000 lawyers to back them up. The Japanese, who have only 10,000 registered lawyers, regard contingencies to be force majeure and consider that contracts should be sensibly reworked and modified at another meeting or negotiation.

The French tend to be precise in the drawing up of contracts, but other Latins require more flexibility in adhering to them. An Italian or Argentinean sees the contract as either an ideal scheme in the best of worlds, which sets out the prices, delivery dates, standards of quality and expected gain, or as a fine project that has been discussed. But the way they see it, we do not live in the best of worlds, and the outcome we can realistically expect will fall somewhat short of the actual terms agreed. Delivery of payment may be late, there may be heated exchanges of letters or faxes, but things will not be so bad that further deals with the partner are completely out of the question. A customer who pays six months late is better than one who does not pay at all. A foreign market, however volatile, may still be a better alternative to a stagnating or dead-end domestic one.

If Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians have a problem with the ethics of breaking or modifying a contract, they have an even greater one with those of propriety. Which culture or authority can deliver the verdict on acceptable standards of behavior or appropriate conduct of business?

Italian flexibility in business often leads Anglo-Saxons to think they are dishonest. They frequently bend rules, break or get around some laws and put a very flexible interpretation on certain agreements, controls and regulations. There are many gray areas where shortcuts are, in Italian eyes, a matter of common sense. In a country where excessive bureaucracy can hold “business” up for months, smoothing the palm of an official or even being related to a minister is not a sin. It is done in most countries, but in Italy they talk about it.

When does lavish entertaining or regular gift giving constitute elegant bribery or agreeable corruption? French, Portuguese and Arab hosts will alternate the negotiation sessions with feasting far superior to that offered by the Scandinavian cafeteria or British pub lunch. The expense-account-culture Japanese would consider themselves inhospitable if they had not taken their visiting negotiators on the restaurant nightclub circuit and showered them with expensive gifts.

Few Anglo-Saxons or Scandinavians would openly condone making a covert payment to an opposing negotiator, but in practice this is not an uncommon occurrence when competition is fierce. I once heard an American define an honest Brazilian negotiator as one who, when bought, stays bought. More recently the leader of the negotiating team of a large Swedish concern tacitly admitted having greased the palm of a certain South American gentleman without securing the contract. When the Swede quietly referred to the payment made, the beneficiary explained, “Ah, but that was to get you a place in the last round!”

Judgments on such procedures are inevitably cultural. Recipients of under-the-table payments may see them as no more unethical than using one’s influence with a minister (who happens to be one’s uncle), accepting a trip around the world (via Tahiti or Hawaii) to attend a “conference” or wielding brute force (financial or political) to extract a favorable deal from a weaker opponent. All such maneuvers can be viewed (depending on one’s mindset) as normal strategies in the hard world of business. One just has to build these factors into the deal or relationship.

Cross-cultural factors will continue to influence international negotiation and there is no general panacea of strategies which ensure quick understanding. The only possible solutions lie in a close analysis of the likely problems. These will vary in the case of each negotiation; therefore, the combination of strategies required to facilitate the discussions will be specific on each occasion. Before the first meeting is entered into, the following questions should be answered:

1. What is the intended purpose of the meeting? (Preliminary, fact-finding, actual negotiation, social?)

2. Which is the best venue?

3. Who will attend? (Level, number, technicians?)

4. How long will it last? (Hours, days, weeks?)

5. Are the physical arrangements suitable? (Room size, seating, temperature, equipment, transportation, accommodation for visitors?)

6. What entertainment arrangements are appropriate? (Meals, excursions, theater?)

7. How much protocol does the other side expect? (Formality, dress, agendas?)

8. Which debating style are they likely to adopt? (Deductive, inductive, freewheeling, aggressive, courteous?)

9. Who on their side is the decision maker? (One person, several, or only consensus?)

10. How much flexibility can be expected during negotiation? (Give-and-take, moderation, fixed positions?)

11. How sensitive is the other side? (National, personal?)

12. How much posturing and body language can be expected? (Facial expressions, impassivity, gestures, emotion?)

13. What are the likely priorities of the other side? (Profit, long-term relationship, victory, harmony?)

14. How wide is the cultural gap between the two sides? (Logic, religion, political, emotional?)

15. How acceptable are their ethics to us? (Observance of contracts, time frame?)

16. Will there be a language problem? (Common language, interpreters?)

17. What mechanisms exist for breaking deadlocks or smoothing over difficulties?

18. To what extent may such factors as humor, sarcasm, wit, wisecracking and impatience be allowed to spice the proceedings?

Good answers to the questions in the preceding checklist will help to clear the decks for a meeting that will have a reasonable chance of a smooth passage. It is to be hoped that the other side has made an attempt to clarify the same issues. The French often hold a preliminary meeting to do just this—to establish the framework and background for discussion. This is very sensible, although some regard the French as being nitpicking in this respect.