The disintegration of the Soviet Union has eliminated the gigantic, multicultural phenomenon constituted by the bewildering assortment of countries, races, republics, territories, autonomous regions, philosophies, religions and credos that conglomerated to form the world’s vastest political union. The cultural kaleidoscope had been so rich it boggled the mind. Its collapse, however, serves to make us focus on something simpler yet unquestionably fecund per se—the culture of Russia itself.

It is only too easy to lump Soviet ideology and the Russian character together, since during 70 years of strife and evolution, one lived with the other. Yet Soviet Communist Russian officials were no more than one regimented stream of Russian society—a frequently unpopular, vindictive and shortsighted breed at that, although their total grasp of power and utter ruthlessness enabled them to remain untoppled for seven decades.

Russian individuality was obliged in a sense to go underground, to mark time in order to survive, but the Russian soul is as immortal as anyone’s. Its resurrection and development in the twenty-first century is of great importance to us all.

Some of the less attractive features of Russian behavior in the Soviet period—exaggerated collectivism, apathy, suspicion of foreigners, pessimism, petty corruption, lack of continued endeavor, inward withdrawal—were visible hundreds of years before Vladimir Lenin or Karl Marx were born. Both Czarist and Soviet rule took advantage of the collective, submissive, self-sacrificial, enduring tendencies of the romantic, essentially vulnerable subjects under their sway. Post-Soviet Russian society is undergoing cataclysmic evolution and change, and it remains to be seen how some eventual form of democracy and the freeing of entrepreneurial spirit will affect Russia’s impact on the rest of the world.

The two chief factors in the formation of Russian values and core beliefs were over and above any governmental control. These prevailing determinants were the incalculable vastness of the Russian land and the unvarying harshness of its climate. The boundless, often indefensible steppes bred a deep sense of vulnerability and remoteness that caused groups to band together for survival and develop hostility to outsiders.

Climate (a potent factor in all cultures) was especially harsh on Russian peasants, who were traditionally forced, virtually, to hibernate for long periods, then struggle frantically to till, sow and harvest during the short summer. Anyone who has passed through Irkutsk or Novosibirsk in the depth of winter can appreciate the numbing effect of temperatures ranging from minus 5–40 degrees Fahrenheit (20–4 degrees Celsius).

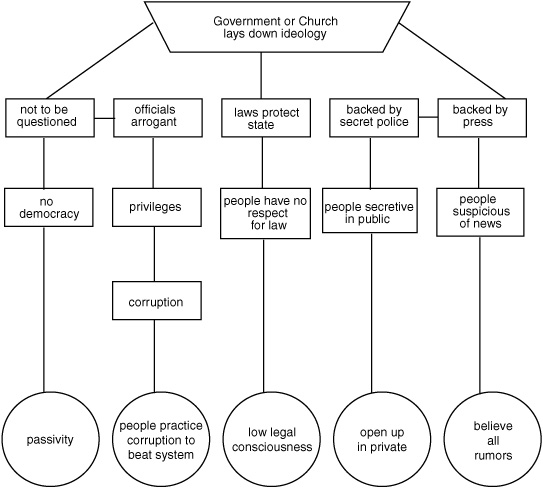

The long-suffering Russian peasants, ill-favored by cruel geography and denied (by immense distances and difficult terrain) chances to communicate among themselves, were easy prey for those with ambitions to rule. Small uneducated groups, lacking in resources and cut off from potential allies, are easy to manipulate. The Orthodox Church, the Czars, the Soviets, all exploited these hundreds of thousands of pathetic clusters of backward rustics. Open to various forms of indoctrination, the peasants were bullied, deceived, cruelly taxed and, whenever necessary, called to arms. Russians have lived with secret police not just in KGB times, but since the days of Ivan the Terrible, in the sixteenth century. Figure 40.1 shows how oppressive, cynical governance over many centuries developed further characteristics—pervasive suspicion, secrecy, apparent passivity, readiness to practice petty corruption, disrespect for edicts—as added ingredients to the traditional Russian pessimism and stoicism in adversity.

Figure 40.1 Governance of Russia

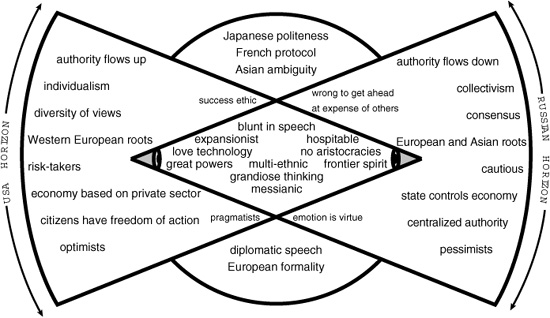

If all this sounds rather negative, there is good news to come. Although resorting to expediency for survival, Russians are essentially warm, emotional, caring people, eagerly responding to kindness and love, once they perceive that they are not being “taken in” one more time. Finns—victims of Russian expansionism on more than one occasion—readily acknowledge the warmth and innate friendliness of the individual Russian. Even Americans, once they give themselves time to reflect, find a surprising amount of common ground. Both peoples distrust aristocrats and are uncomfortable, even today, with the smooth eloquence of some Europeans. Bluntness wins friends both in Wichita and Kazan. Both nations think big and consider they have an important role to play—a “mission” in world affairs.

Our familiar “horizon” comparison in Figure 40.2 shows that while Russians and Americans are destined by history and location to see the world in very different manners, there is sufficient commonality of thinking to provide a basis for fruitful cooperation. Their common dislikes are as important in this respect as some of their mutual ambitions.

As far as their attitudes to the world in general are concerned, how do Russians see the rest of us and—importantly—how do they do business? While it is clear that they are a society in transition, certain features of their business culture inevitably reflect the style of the command economy that organized their approach to meetings over a period of several decades. Russian negotiating characteristics, therefore, not only exhibit traditional peasant traits of caution, tenacity and reticence, but indicate a depth of experience born of thorough training and cunning organization. They may be as follows:

![]() They negotiate like they play chess: they plan several moves ahead. Opponents should think of the consequences of each move before making it.

They negotiate like they play chess: they plan several moves ahead. Opponents should think of the consequences of each move before making it.

![]() Russian negotiators often represent not themselves, but part of their government at some level.

Russian negotiators often represent not themselves, but part of their government at some level.

![]() Russian negotiating teams are often composed of veterans or experts; consequently, they are very experienced.

Russian negotiating teams are often composed of veterans or experts; consequently, they are very experienced.

Figure 40.2 Russian/U.S. Horizons

![]() Sudden changes or new ideas cause discomfort, as they have to seek consensus from higher up.

Sudden changes or new ideas cause discomfort, as they have to seek consensus from higher up.

![]() Negotiations often relate the subject under discussion to other issues outside the scope of the negotiations. This may not be clear to the other side.

Negotiations often relate the subject under discussion to other issues outside the scope of the negotiations. This may not be clear to the other side.

![]() Russians often regard willingness to compromise as a sign of weakness.

Russians often regard willingness to compromise as a sign of weakness.

![]() Their preferred tactic in case of deadlock is to display patience and “sit it out”; they will only abandon this tactic if the other side shows great firmness.

Their preferred tactic in case of deadlock is to display patience and “sit it out”; they will only abandon this tactic if the other side shows great firmness.

![]() The general tendency is to push forward vigorously if the other side seems to retreat, to pull back when meeting stiff resistance.

The general tendency is to push forward vigorously if the other side seems to retreat, to pull back when meeting stiff resistance.

![]() Delivery style is often theatrical and emotional, intended to convey clearly their intent.

Delivery style is often theatrical and emotional, intended to convey clearly their intent.

![]() Like Americans, they can use “tough talk” if they think they are in a stronger position.

Like Americans, they can use “tough talk” if they think they are in a stronger position.

![]() They maintain discipline in the meeting and speak with one voice. When Americans or Italians speak with several voices, the Russians become confused about who has real authority.

They maintain discipline in the meeting and speak with one voice. When Americans or Italians speak with several voices, the Russians become confused about who has real authority.

![]() Russians often present an initial draft outlining all their objectives. This is only their starting position and far from what they expect to achieve.

Russians often present an initial draft outlining all their objectives. This is only their starting position and far from what they expect to achieve.

![]() They often make minor concessions and ask for major ones in return.

They often make minor concessions and ask for major ones in return.

![]() They may build into their initial draft several “throwaways”—things of little importance which they can concede freely, without damaging their own position.

They may build into their initial draft several “throwaways”—things of little importance which they can concede freely, without damaging their own position.

![]() They usually ask the other side to speak first, so they may reflect on the position given.

They usually ask the other side to speak first, so they may reflect on the position given.

![]() They are sensitive and status conscious and must be treated as equals and not “talked down to.”

They are sensitive and status conscious and must be treated as equals and not “talked down to.”

![]() Their approach to an agreement is conceptual and all-embracing, as opposed to American and German step-by-step settlement.

Their approach to an agreement is conceptual and all-embracing, as opposed to American and German step-by-step settlement.

![]() Acceptance of their conceptual approach often leads to difficulties in working out details later and eventual implementation.

Acceptance of their conceptual approach often leads to difficulties in working out details later and eventual implementation.

![]() They are suspicious of anything that is conceded easily. In the Soviet Union days, everything was complex.

They are suspicious of anything that is conceded easily. In the Soviet Union days, everything was complex.

![]() Personal relationships between the negotiating teams can often achieve miracles in cases of apparent official deadlock.

Personal relationships between the negotiating teams can often achieve miracles in cases of apparent official deadlock.

![]() Contracts are not as binding in the Russian mind as in Western minds. Like Asians, Russians see a contract as binding only if it continues to be mutually beneficial.

Contracts are not as binding in the Russian mind as in Western minds. Like Asians, Russians see a contract as binding only if it continues to be mutually beneficial.

A study of this list may lead you to the conclusion that Russian negotiators are not easy people to deal with. There is no reason to believe that the development of entrepreneurism in Russia, giving added opportunities and greater breadth of vision to those who travel in the West, will make Russians any less effective around the negotiating table. Westerners may hold strong cards and may be able to dictate conditions for some length of time, but the ultimate mutual goal of win–win negotiations will only be achieved through adaptation to current Russian mentality and world attitudes.

![]() If you have strong cards, do not overplay them. Russians are proud people and must not be humiliated.

If you have strong cards, do not overplay them. Russians are proud people and must not be humiliated.

![]() They are not as interested in money as you are; therefore, they are more prepared to walk away from a deal than you.

They are not as interested in money as you are; therefore, they are more prepared to walk away from a deal than you.

![]() Russians are people- rather than deal-oriented. Try to make them like you.

Russians are people- rather than deal-oriented. Try to make them like you.

![]() If you succeed, they will conspire with you to “beat the system.” Indicate your own distrust of blind authority or excessive bureaucracy as often as you can.

If you succeed, they will conspire with you to “beat the system.” Indicate your own distrust of blind authority or excessive bureaucracy as often as you can.

![]() Do them a favor early on, but indicate it is not out of weakness. The favor should be personal, rather than relating to the business being discussed.

Do them a favor early on, but indicate it is not out of weakness. The favor should be personal, rather than relating to the business being discussed.

![]() Do not be unduly influenced by their theatrical and emotional displays, but do show sympathy with the human aspects involved.

Do not be unduly influenced by their theatrical and emotional displays, but do show sympathy with the human aspects involved.

![]() When you show your own firmness, let some glimmer of kindness shine through.

When you show your own firmness, let some glimmer of kindness shine through.

![]() Drink with them between meetings if you are able to; it is one of the easiest ways to build bridges.

Drink with them between meetings if you are able to; it is one of the easiest ways to build bridges.

![]() They like praise, especially related to Russian advances in technology, but also about their considerable artistic achievements.

They like praise, especially related to Russian advances in technology, but also about their considerable artistic achievements.

![]() Do not talk about World War II. They are sensitive about war talk and consider most Russian wars as defensive ones against aggressive neighbors. They have not been given your version of history.

Do not talk about World War II. They are sensitive about war talk and consider most Russian wars as defensive ones against aggressive neighbors. They have not been given your version of history.

![]() They particularly love children, so exchanging photographs of your children is an excellent way to build relationships.

They particularly love children, so exchanging photographs of your children is an excellent way to build relationships.

![]() They respect old people and scorn Americans’ treatment of the elderly. Mention your own family closeness, if appropriate.

They respect old people and scorn Americans’ treatment of the elderly. Mention your own family closeness, if appropriate.

![]() Indicate your human side—emotions, hopes and aspirations. They are much more interested in your personal goals than in your commercial objectives.

Indicate your human side—emotions, hopes and aspirations. They are much more interested in your personal goals than in your commercial objectives.

![]() Bear in mind during your business discussions that their priorities will be personal relationships, form and appearance, and opportunity for financial gain—in that order.

Bear in mind during your business discussions that their priorities will be personal relationships, form and appearance, and opportunity for financial gain—in that order.

![]() The Eastern and Western elements in their makeup often cause them to appear schizophrenic. Do not let this faze you—the other face will always reappear in due course.

The Eastern and Western elements in their makeup often cause them to appear schizophrenic. Do not let this faze you—the other face will always reappear in due course.

![]() They have, in their history, never experienced democracy; therefore, do not expect them to be automatically egalitarian, fair, even-handed and open to straightforward debate. Explain to them clearly how you think about such matters and how you are basically motivated by these factors.

They have, in their history, never experienced democracy; therefore, do not expect them to be automatically egalitarian, fair, even-handed and open to straightforward debate. Explain to them clearly how you think about such matters and how you are basically motivated by these factors.

![]() Anything you introduce as an official directive or regulation they will distrust. What you indicate as a personal recommendation, though, they will embrace.

Anything you introduce as an official directive or regulation they will distrust. What you indicate as a personal recommendation, though, they will embrace.

![]() Russians are basically conservative and do not accept change easily. Introduce new ideas slowly and keep them low key at first.

Russians are basically conservative and do not accept change easily. Introduce new ideas slowly and keep them low key at first.

![]() They often push you and understand being pushed, but they rebel if they feel the pressure is intolerable. Try to gauge how far you can go with them.

They often push you and understand being pushed, but they rebel if they feel the pressure is intolerable. Try to gauge how far you can go with them.

![]() Dissidence in general is not popular with them, as security has historically been found in group, conformist behavior. Do not try to separate a Russian from his or her “group,” whatever that may be.

Dissidence in general is not popular with them, as security has historically been found in group, conformist behavior. Do not try to separate a Russian from his or her “group,” whatever that may be.

![]() They love conversation. Do not hesitate to unburden yourself in front of them. Like Germans, they are fond of soul-searching.

They love conversation. Do not hesitate to unburden yourself in front of them. Like Germans, they are fond of soul-searching.

![]() They achieve what they do largely through an intricate network of personal relationships. Favor is repaid by favor. They expect no help from officials.

They achieve what they do largely through an intricate network of personal relationships. Favor is repaid by favor. They expect no help from officials.

![]() Like Germans, they enter meetings unsmiling. Like Germans, they can be quickly melted with a show of understanding and sincerity.

Like Germans, they enter meetings unsmiling. Like Germans, they can be quickly melted with a show of understanding and sincerity.

![]() When they touch another person during conversation, it is a sign of confidence.

When they touch another person during conversation, it is a sign of confidence.

Motivating Factors

![]() Emphasize the breadth of Russian horizons and viewpoints.

Emphasize the breadth of Russian horizons and viewpoints.

![]() Show that their many characteristics are mirrored in Western Europe: compassion in Italy, sentimentality in Germany, love of tradition in Britain, warmth and generosity in Spain, artistic achievements in France.

Show that their many characteristics are mirrored in Western Europe: compassion in Italy, sentimentality in Germany, love of tradition in Britain, warmth and generosity in Spain, artistic achievements in France.

![]() Stress their “Europeanness.”

Stress their “Europeanness.”

![]() Envisage their eventual entry into the EU.

Envisage their eventual entry into the EU.

![]() Praise their volte-face after the demise of communism.

Praise their volte-face after the demise of communism.

![]() Point out that traditional Russian traits have survived the vicissitudes of history.

Point out that traditional Russian traits have survived the vicissitudes of history.

![]() Focus on Russian positive characteristics: warmth, generosity, compassion, artistry and aesthetics, stamina, powers of improvisation, deep friendships.

Focus on Russian positive characteristics: warmth, generosity, compassion, artistry and aesthetics, stamina, powers of improvisation, deep friendships.

![]() Offer help and advice where appropriate.

Offer help and advice where appropriate.

![]() Show camaraderie.

Show camaraderie.

![]() Indicate trust.

Indicate trust.

Avoid

![]() Talking down to them.

Talking down to them.

![]() Discussing past failures.

Discussing past failures.

![]() Causing loss of face.

Causing loss of face.

![]() Bad manners.

Bad manners.

![]() Being too casual or flippant.

Being too casual or flippant.

![]() Paying insufficient attention or respect to elderly people.

Paying insufficient attention or respect to elderly people.

![]() Pushy behavior.

Pushy behavior.