If you don’t have an emotional hook, baby, you don’t have a prayer.

—Paul Stevens, I Can Sell You Anything, 1972

4

Music, Mood, and Television

The Use of Emotion in Advertising Music in the 1950s and 1960s

Introduction

One of the most striking aspects of early advertising music and discourses around it was that affect or mood was almost never mentioned, even though emotional selling was already an important aspect of print advertising from early in the twentieth century, as historians of advertising have shown.1 Music was chosen for its ability to be evocative—as peppy sounds for effervescent ginger ale, for example—or cheery, to sell practically anything. Judging by the sound of these jingles, affect was surely a consideration—dirges were not employed to sell anything. But affect was largely an unspoken concern. This, of course, makes sense, because with radio one cannot see the product being sold: it had to be animated with music, given a personality. After the rise of television, the practice of imparting a personality to a product didn’t disappear, but was joined by the now-ubiquitous strategy of using music for emotional manipulation, providing an affective underpinning for visuals.

While the postwar moment brought a number of important changes and strategies in the world of advertising, this chapter will focus on the question of emotion in music, since it continues to be central to how advertising music is conceptualized today; the following chapter will return to the history of the jingle, including its decline, to examine other shifts in the industry following World War II.

Heightened Consumption after World War II

The onset of the Cold War brought with it an increased sense of the importance of consumption as a civic duty that differentiated Americans from Soviets, but it did not vanquish the upbeat musical sales pitch in the form of the jingle. The Cold War, did, however, usher in a new strategy for the use of music in advertising and the promotion of new forms of American consumer culture. Lizabeth Cohen has written of two competing ideologies with respect to consumption in the twentieth century, the “citizen consumer,” who consumed out of a sense of civic duty during the Depression and World War II, and the “purchaser consumer” of the same era, whose consumption was based more on self-interest. But after the war, she argues, another ideal emerged, that of the “purchaser as citizen” in a new “Consumer’s Republic,” in which consumers acting out of their personal desires could view themselves as acting in the public interest, helping to bring the country out of its Depression doldrums.2

Cohen writes vividly of the postwar moment after the initial boom in purchasing. What was to come next? Manufacturers made more products, and in a greater variety, including what were known in the industry as “parity products”—goods that were scarcely different from one another, giving the impression of a wealth of products in contrast to the few and standardized goods available under the previous regime of capitalism.3 Obsolescence was planned, even accelerated.

American consumption reached new heights in this period, driven in large part by the advertising industry, which grew enormously in this era, finding new ways to sell by using psychology. In 1945, total billings of the ten largest agencies were $383,000,000; by 1960, billings had more than quadrupled, to $1,592,800,000.4 Archival documents bear out the increased role assumed by advertising agencies. A J. Walter Thompson Company in-house publication from 1955 entitled Huge New Markets said:

The attainment of new levels of prosperity will depend largely on our recognition that expanding consumption through mass movements to better living standards is the key to keeping our production and employment high—and is the key to a strong defense and a balanced budget.

This is a challenge to marketing, because the change from a production economy, heavily influenced by government, to a consumption economy of individual enterprise places the burden on selling, on finding needs and creating desires and on improving products or developing new products to meet these needs and potential desires.

We have experienced the miracle of production—now, through the magic of consumption, we have the opportunity to keep our economy dynamic and growing. The magic of consumption offers an opportunity for utilizing our increased productive ability in the positive form of a better standard of living.5

The document continues by citing statistics about federal expenditures and increasing consumption, then returns to exhortative mode, noting that American consumers’ spending habits are difficult to change.

There is the task of educating the American people to accept and work for the higher standard of living that their productive ability warrants. Selling and advertising can play a major part in the constructive urge to better living standards. And, as the standard of living advances along with productivity, the new and expanded markets thus created will have a magical influence on industrial growth and progress, on private financing and on increasing government revenues.6

It isn’t necessary to point out the success of this approach, which, even after the onset of the Great Recession of the 2000s and 2010s, shows little sign of losing its adherents.

Motivation Research

The newfound interest in emotion in the 1950s was in part a product of the penchant for Freudianism and other psychological theories of the time, for psychoanalysis was on the rise, becoming commonplace among the urban middle classes.7 Sherry B. Ortner has written of the Freudianism fad in the 1950s and the ways that it pervaded American culture, thematized in many forms of popular culture, in films such as Forbidden Planet from 1956, in which the threat proves to be not a creature but the id of the chief scientist. And there is Grace Metalious’s novel Peyton Place from the same year, in which an important male character, whose father is dead, receives enemas every night from his mother and later turns out to be gay.

Despite the interest in Freud held by advertising agencies, introducing the idea of the utility of music as a mood manager to advertising was a slow process, for as many have observed, early television was conceptualized simply as “radio with pictures”; the transition from radio to television was slow and arduous. Yet the almost complete absence of discussions of mood and music in the early television era is still striking, since in the realm of film music, even before sound, mood was central.8 What is noteworthy in the case of film versus radio is the distinction between them with respect to the question of affect, even though radio and film production became intertwined and interrelated early on.9 Before World War II, there were occasional considerations of the question, though they were rare; even a 1935 volume entitled The Psychology of Radio confines itself largely to questions of audience preferences, which was what most publications were concerned with in this era, though near the end, the book included a brief meditation on music’s ability to express “the basic feeling-tone—the mood, emotion, or desire—that underlies all experience.”10

But such writings were unusual. Discussions of the importance of affect in radio do not enter mainstream advertising music discourse until the late 1950s (and by the 1990s became something of an academic subfield that I will discuss briefly below). In part, these early considerations were driven, I believe, not only by the advent of television but also by several other factors: the research of Ernest Dichter, whose ideas were further promoted by newspaper advertising man Pierre Martineau in a book published in 1957, and the critique of Dichter’s work that appeared in the best seller The Hidden Persuaders by Vance Packard, also from 1957. The use of insights from psychology in advertising had a long history before Dichter (perhaps the most famous marker of the promise the industry felt that psychology offered was J. Walter Thompson Company’s hiring of the well-known behavioral psychologist John B. Watson in 1920), but it was Dichter’s development of “motivation research” that marked a new era in the use of psychology in advertising.

Ernest Dichter (1907–91) earned a PhD in psychology from the University of Vienna and immigrated to New York City in 1938, where he worked for five years under Paul Lazarsfeld, the pioneer in audience research, and later founded the Institute for Motivational Research in 1946. Not without a flair for self-promotion, Dichter became rather notorious when he concluded in a study for Chrysler in 1939 that men viewed sedans as their wives but convertibles as mistresses; Dichter advised Chrysler to use convertibles in the showroom window as bait to draw male customers in, a strategy that substantially increased Chrysler’s sedan sales.11

Another one of Dichter’s arguments that illustrates his perspective concerned ice cream.

Most ice cream advertising . . . strives to impress the public with the superior quality and flavor of one particular ice cream. These claims are augmented and illustrated with beautiful dishes of ice cream. To the advertiser the combination of copy and illustration adds up to good advertising. But is it enough—should not his goal be greater?

A psychological study showed the “voluptuous” nature of ice cream to be one of its main appeals. In talking about ice cream, people commented: “You feel you can drown yourself in it,” and “You want to get your whole mouth into it.” Nothing, however, in the advertising produced the effect which this psychological study showed they should have. The advertisements were not designed so as to satisfy people’s desire for voluptuousness. Instead they created a feeling of neatness, an expectancy of sober enjoyment in eating X ice cream—all far removed from the emotionally loaded feelings most people have for ice cream.12

Not surprisingly, Dichter thought that the more quantitative kinds of approaches in other types of audience research were flawed.

What struck me, coming from clinical psychology and psychoanalytic research, was that people were being asked through questionnaires why they were buying milk . . . and I just couldn’t swallow that. It was almost comparable to asking people why they thought they were neurotic or to a physician asking a patient whatever disease he thought he had. I started fighting against that.13

To improve these superficial interviews, Dichter developed a technique he called “depth interviewing,” which, he wrote, is “a procedure by which the respondent achieves an insight in to his own motivations. In other words, for the respondent it is a sort of introspective method.” “In a depth interview,” Dichter continued, “the interviewer attempts to bring about a full and spontaneous expression of attitudes from the respondent.”14 Elsewhere, Dichter described the depth interview as having been designed “to elicit the freest possible associations on the part of the respondent,” as a way of determining “the meaning of the consumer’s behavior rather than relying strictly upon her own explanation.”15 This and other techniques, some of which were more quantitative, could help the interviewer understand if people liked a certain brand of gum because it was fun (“bubble blowing”) or because it evoked a feeling of aggressiveness (“tougher chewing”).16

Dichter’s influential ideas were popularized by Pierre Martineau, director of research and marketing for the Chicago Tribune, who was one of the first to proselytize for the importance of affect in advertising: “One of the great reawakenings of human thought has been occasioned by the rediscovery of feeling. For 300 years men have worshiped at the altar of Reason,” he wrote.17 Martineau believed that artists, as well as parents and salesmen, had always understood the importance of feelings in shaping human behavior, but rationality denied this.18 Admitting that advertising practices already made much use of affective devices, Martineau said that affect had almost no presence in advertising theory, and that many of the affective qualities of ads were removed at the insistence of people on the business side because those on the creative side didn’t have a way to articulate the importance of affect. But, he asserted, even the best sales techniques needed some sort of affective device to accompany them.19 Martineau thus believed that the practices of advertising must change, making room for feeling and emotions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, not everyone viewed positions such as Dichter’s and Martineau’s with favor. Vance Packard attacked Dichter in The Hidden Persuaders, believing that America had moved into a world of Big Brother, and that “the use of mass psychoanalysis to guide campaigns of persuasion has become the basis of a multimillion-dollar industry.”20 Successfully perceiving advertisers’ and marketers’ strategy, Packard argued that one of the reasons for the rise of “motivation research” was that the post–World War II glut of products on the market that weren’t very different from one another—parity products—necessitated a different kind of advertising, one that didn’t rely on logic or assumptions of the rational consumer. Betty Friedan also assailed Dichter in The Feminine Mystique for his culpability in attempting to interpellate women as housewives and mothers and convincing them that commodities could provide what they lacked in their lives.21

Music

It is not clear if musicians were participating in these debates, though surely some were familiar with Packard’s best-selling book. Nonetheless, the idea of the utility of employing music for its affective qualities was slow to take hold in the world of advertising. Even in the late 1950s, advertising textbook authors were still discussing emotion in simplistic ways that show no greater degree of sophistication than the few prewar writings.22 The only shift from the straightforwardly happy jingle in this era began around the same time that the United States entered World War II, when the march began to be used frequently as the basis for radio, and later television, jingles (example 4.1, “L-A-V-A,” a jingle that was introduced on the CBS radio program The FBI in Peace and War in about 1944).23 But most marches remained upbeat, whether selling cigarettes or breakfast cereal or razors (Gillette, “To Look Sharp,” 1953, example 4.2, by Mahlon Merrick) or, especially, beer, obviously drawing on the German beer-drinking tradition (“My Beer Is Rheingold, the Dry Beer!,” 1950s, example 4.3). Affectively, these examples are quite straightforward, but in their exhortative directness, they help make clear the combining of military and industrial interests that were coupled with the increasing pressure on Americans to conceptualize consumption as an important civic and patriotic duty during the Cold War. The martial nature of many jingles lasted almost as long as the form itself.

Nonetheless, advertising agencies were beginning, however feebly, to become more interested in the effectiveness of music used in advertising with respect to the question of emotion by the very late 1950s; a 1959 study revealed that music was used most when the advertising copy was motivational rather than informational.24 A memorandum from the J. Walter Thompson Company the following year said that not much was known about the question of the effectiveness of music, but that “basically, it is felt that music . . . helps set and maintain the feel or mood of the commercial. It complements the copy and picture portion while acting as a unifying cohesive force. It gets under the viewers [sic] skin and helps make the commercial something more than just ‘a commercial.’ ”25 And an advertising practitioner urged his readers in 1961 to recognize the potential of music in commercials, pointing out how music in advertising could learn from the use of music in film and television. Like several publications in this era, this article mentioned Henry Mancini’s theme music for the television program Peter Gunn: jazzy, dark, foreboding. The main argument the author forwards for the use of music in commercials concerns the service that music can provide in establishing mood.26

Yet sophisticated conceptions of music and emotion were slow in coming. In 1959, Beneficial Finance decided to employ music in its commercial; the “theory was that additional warmth and public understanding would be conveyed via the musical notes,” according to an article in the trade press in 1962.27 Phil Davis, a leading jingle composer in the 1950s and 1960s, was hired to make those notes, explaining his process thus:

The lyrics and music of a service commercial, like Beneficial Finance, go beyond the literal.

A man may have a pressing financial problem, which may or may not be in the forefront of his consciousness, but from which he basically seeks relief.

Literally, this is a serious situation; yet, to write lugubrious lyrics or music would deepen the severity of the pressure. So the musical commercial producer does the inverse. He composes happy lyrics and music that suggest to the listener a possible happy solution to his problem.

For example, interspersed between the voice of the announcer and the music of the commercial, you hear the following cheerful, optimistic lyrics: Call for money the minute you want it. . . .

[The commercials] are written instrumentally to sound happy by the use of the celeste, orchestra bells, or bright, gay woodwinds—and nothing in a minor key.28

The article later reprints the jingle’s lyrics, which were underlain by a “celeste background.”

When the rise of rock ’n’ roll in the 1950s threatened the livelihood of most Broadway composers, some entered the world of jingle composition. When these musicians, accustomed to writing music that engaged with listeners’ emotions, encountered the affectively undeveloped world of jingles, there was a telling collision of the underlying ideologies of the two realms. Said Harold Rome in 1961, who wrote music for a Sanka commercial, “I can’t get any emotion into Sanka coffee.”29 Affect was long a concern of these composers but still foreign to the world of advertising music in this period.

Two Mitches and a Roy: Leigh, Miller, and Eaton

The composer who, perhaps more than anyone else, helped broaden the emotionality of music used in advertising was Mitch Leigh (1928–), who formed Music Makers Inc. in 1957, which was emphatically not a jingle company (though it would please its clients that wanted one) but a company devoted to providing music that established the underlying mood of the commercial. Leigh, a former student of Paul Hindemith at the Yale School of Music, had impeccable credentials as a classical composer and also possessed strong ideas about the power of music to motivate, as well as the obsolescence of jingles. His bold pronouncements on the lack of usefulness of the jingle—an unsophisticated kind of music in his view, in part, I think, because of its affective one-dimensionality—helped him promote the idea that commercial music could be something more: “Jingles as we’ve known them for the past twenty-five years are dying. In fact they’re dead right now and what is left is just the body cooling off,” he said in 1960.30 Elsewhere, Leigh compared his company’s approach to the use of mood music in film. Today, this is the norm, but in the early 1960s, it was a novel idea.31

Using music for emotional purposes entered advertising practice through film, which, of course, had employed music to provide emotional underpinnings for decades. In advertising, using music this way was called “prescoring,” referring to the fact that the instrumental music was recorded first, before the voice and visuals. Commercials began to be prescored in the late 1950s, and Leigh was a major proponent, for with prescoring, composers could tie moods with the visual with more nuance than was possible otherwise.32 Leigh thought that music was the last of the arts to be used in marketing, but that, “in stimulating an emotional response to a product [music] can be advertising’s most powerful instrument of communication,” he said in 1966.33 Leigh also said that he wanted to give clients “the most effective tool for producing emotions for remembering a product when you’re in a supermarket crammed with different items.”34

Other interviews with Leigh from the 1950s and 1960s make frequent reference to the importance of emotion in advertising. For him, the main question was, does the everyday person react emotionally to an ad?35 In another interview, he said, “Music gives a product emotional memorability.”36 Leigh said in a 1958 publication that his company called its approach “musical psychology,” which referred to the “physical relationships of sounds, pitches, nuances, rhythms, meters, melodies and harmonies” with which “we are able to invade the unconscious of the viewer and affect his human sensibilities; thereby setting him up for the commercials’ ‘haymaker.’ ”37 In an interview, I asked him about the role of emotion in music. He stated bluntly, “Emotion is what advertising is,” and, “I really honestly believe to this day that people buy on the basis of emotion, they react to emotion.” Leigh told me that his company was successful, he believed, because of the emotional selling of products: “The one thing that remains totally emotional is music, and if it’s used well . . . we sold a lot of products.”38

Figure 4.1 Mitch Leigh. (Courtesy of Mitch Leigh.)

Leigh explained his compositional approach to commercial music in a 1959 Wall Street Journal interview with an example. A commercial for Ford automobiles entitled “Backseat Blues” was designed to convey the impression that other cars were less roomy by employing images of people contorting themselves getting in and out of these competing vehicles; Leigh’s music changed meter with them. “Each meter change gives the viewer an uncomfortable experience,” he said, which, he thought, entered the subconscious (example 4.4).39 I have been able to hear the music to this commercial (but not see the video), and the meter changes are quite audible. At the same time, however, the affect of the commercial is relentlessly upbeat, in a vocal jazz idiom of the era.40

Other commercials employed different techniques. A commercial for Renault used French horns and timpani in a crescendo at the commercial’s end to leave listeners “with the impression of a spritely [sic] car with a peppy getaway.”41 For an antacid commercial, Leigh’s music opened with the sounds of a calliope to communicate the madness of contemporary life, moving to soothing music as the tablet took effect.42

While Leigh was probably the most vocal of proponents of the employment of affect in advertising music in this era, he wasn’t the only person advocating more sophisticated approaches to music and emotion in advertising. Mitch Miller, an influential figure in the commercial music world in this period as head of A&R (artists and repertoire) at Columbia Records, wrote in 1956:

I remember asking Rodgers and Hammerstein how they decided what to put to music, and what to leave as dialogue. And they replied that they used music and songs only when it became impossible to convey an emotional feeling by words alone. And the same should apply to music spots. If the music does not heighten the emotional impact of your message—better leave it spoken.43

And an article from April 1961 on Miller presented the idea of using emotion in music as an innovation.44 Miller, like many in this period, believed that music could serve a subliminal function in commercials. The example provided is for the 1959 Ford, which the company wanted to hype for its economy features. A trade press article wrote:

The agency’s writers felt that to do this, they would have to list all the major savings features. Given 60 seconds, only an announcer would be able to say all that had to be said. It couldn’t be sung because getting all the nuts and bolts information into an effective and catchy song would be impossible.

Was this a problem music could solve? Because of a heavy emphasis on economy, the agency felt the image of the car as a quality item might suffer. Mr. Miller suggested they back the announcer with a Percy Faith arrangement of the Ford theme full of lush fiddles not ordinarily associated with a low-priced item. The result was a happy one for Ford sales and emphasized another Miller credo: “Words and music must be mated discriminately, or else you’re going to end up with a mongrelized commercial.”45

The other influential figure in advertising music who advocated the use of music for emotional purposes was Roy Eaton, a longtime vice president and music director at Benton and Bowles advertising agency, who, like Leigh and Miller, was a classically trained musician.46 Eaton said in a 1963 article, “Music has an extremely potent emotional function in the sales impact of a commercial. The emotional impact of a commercial is a vital factor in its selling effectiveness.”47 And in an interview, he told me of a 1957 commercial for Kent cigarettes with the then-new micronite filter; in order to convey a feeling of newness, he used modern jazz in the commercial.48 An advertisement for instant Yuban Coffee was thought to require modern sound since instant coffee was a fairly new product, so an arrangement of the original theme was made, this time with “modern chord progressions,” resulting in “a changed harmonic setting, a modern difference.”49

In 1960, Television Magazine argued that as broadcast advertising had become more sophisticated, so, too, had sponsors and their tastes in music, which was increasingly judged by feeling more than anything else.50 Discussions with Eaton revealed that commercials’ factual information didn’t require the use of music for affective purposes. Some of the rationales for using the affective properties of music didn’t always make sense, as in this trade report from 1960 on Yuban Coffee that Eaton worked on: “With General Foods’ Yuban Coffee . . . where the selling story is quality resulting from the blending process (aged coffee beans), an emotional build-up is called for—and accomplished with orchestration and vocal theme (‘deep, dark, delicious Yuban’).”51

Figure 4.2 Roy Eaton. (Courtesy of Roy Eaton; photo by Ken Howard.)

This article about Eaton provides several useful examples, for it points out the differing conceptions of the use of music in this era. One example was for Prell shampoo, which showed a sexy woman using the product; the copy employed only 44 words (we are informed that 150 is the norm for a sixty-second commercial). Eaton

went to a musical style similar to [Maurice] Ravel for two arrangements: one made use of two flamenco guitars, the other used ten instruments, including French horns, trumpet, violin, harp, flute and drums. Human voices were also used in the latter arrangement for some of the copy phrasing. The overall effect is as sweepingly sensuous and pleasurable as the core of the Prell message.52

The other example was for Zest soap, which “also reflects emotional personal product involvement”; the commercial showed a mother and small daughter being caught in the rain. The task for this commercial, according to the article’s author, “was to evoke reminiscence of the clean, fresh feeling of rain to a child and translate this into the type of physical sensation Zest will give to an adult.” Eaton’s solution was to concoct what he called “ ‘a one-minute Peter and the Wolf ’ ”—that is, a more descriptive kind of musical treatment.

Orchestration was for ten instruments—chime effect for rain, violins for sweep, cymbal and woodwinds. In translating character to musical instrument (to give each character a representative musical “image” or “voice”), the daughter was represented by a flute (lightheartedness), the mother by an oboe (maturity).53

The Maturation of a Strategy

After Leigh, Miller, and Eaton in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the emotionality believed to be implicit in music was employed, and referred to, with increasing frequency, in part, it was thought, because of the growing sophistication of audiences. Late in 1963, the New York Times printed an article on the “new wave” of jingles, noting their continuing popularity: “Ad music is in. Way in.” The author noted the new trend toward the increasing sophistication of their sound (“Musical cognoscenti say they hear strains of Busse and Debussy in them”), and compared them to New Wave cinema in their “honesty, intimacy, simplicity, an effort to say more with less, and above all, an attempt to evoke, not provoke, the viewer’s sensibilities.” The main exemplar in this article was Granville (Sascha) Burland, proprietor of C/Hear Services Inc. in New York City. Burland thought, as many did in this era, that there was too much “clutter” on the air, which rendered advertising copy meaningless, and he had nothing but contempt for hard-sell tactics, what he termed “highbutton shoe thinking.”

We’re trying to create a new atmosphere through music—not merely jingles, but to evoke moods, color through original jazz and sounds around us. For years ad music was played on an organ or celesta and it sounded like “Three Blind Mice.” With the tremendous amount of creative talent coming into this field, we’re changing all that.54

Elsewhere, Burland articulated some ideas with respect to affect, matching instrumentation, rhythm, style, and more to create an underlying mood for the commercial.

The possibilities of applying music to ads is [sic] endless. Take a bread ad. Bread is to enjoy, not to safeguard your health. So we’ll compose a flute passage and perhaps some rhythm and strings and come up with a message that will be giddy, such as “Carroway [sic] seeds are better than vitamins.” If it’s a gasoline spot, we’ll give it a jazz orchestration with 35 musicians because you want a “go” feeling. To achieve a sense of dignity or stature we’ll use French horns. For excitement, it’s brass and polyrhythms. If we want to communicate the sensual delights of travel, we might abstract the folk music of the region to give the audience the feel of the place.55

Burland here gave evidence that the advertising musician was beginning to think of his music as did film music composers, though, as we shall see, the conceptualizations of affect continued to become refined. This kind of language, reflecting the growing influence of film music techniques, was also part of the much-vaunted “Creative Revolution” in advertising in the 1960s, when creativity in advertising was given more of a free rein than in previous eras.

By the late 1960s, it appears to have been normal for musicians to discuss mood with copywriters or others involved in the production of ads.56 Questions about mood are largely absent from the trade press by this time, for they had been normalized—people in the industry were talking about music and mood all the time, no longer simply advocating for the use of music to provide mood. It was thus probably inevitable that advertising agencies began to think in terms of writing songs for advertisements that could capture a desired mood. In 1974, a commercial entitled “Sweet Memories” for Kodak was described in the trade press employing a kind of nuance that people were talking about with respect to selling.

The song itself is really the mainspring of the piece. It’s like the clockwork mechanism in the center of a fantastically complex clock—motivating the ebb and flow of feelings and images that run through the film. There are three basic elements in the film: the song, the woman and the place. They are what you remember, what stays with you.

The interesting thing about the making of Sweet Memories was that it involved filming a song. Everything else kind of dovetailed with that original idea. And it was not an easy kind of song to film. It had to do with capturing a feeling, a feeling of evanescing reality, turning into bittersweet memory. The other interesting thing about it was that it did all this in such a way as to make the end product of commercial value. In other words, it sold the product. It made you think nice thoughts about Kodak, and believe that Kodak has a unique way of keeping you and your memories together.57

Commercials such as this, described in sophisticated language of affect (“evanescing reality,” “bittersweet memory”), were leading to a shift in the production of advertising music: music and the mood or moods it was thought to evoke could drive the production of commercials.

Heartsounds

In 1975, when McDonald’s decided that it was unhappy with the famous “You Deserve a Break Today” commercial, its advertising agency found Ginny Redington, a jingle singer and composer who had written some notable jingles in the past. She wrote a new jingle with lyrics by the advertising agency’s copywriter, Keith Reinhard, entitled “You! You’re the One!” Reportedly dressed in jeans, she auditioned the song before the advertising agency suits, who asked her to record the song for use in the commercials. The recording was matched with film showing happy working-class families eating at McDonald’s (examples 4.5 and 4.6). The advertising agency wanted to test the commercial, and concluded that the song was memorable. It then rented the Civic Opera House in Chicago to pitch the commercial to McDonald’s executives, who decided to keep the account at the agency, after having threatened to take it elsewhere.58

The rescue of the account by a song became the talk of Madison Avenue. Time magazine called the jingle the “quintessential ‘me’-decade song,” which concludes with the tagline “We do it all for you.”59 As a result of the success of this song, other agencies began to use music more frequently in their commercials, so that by the late 1970s and early 1980s, many commercials employed a song that made a direct emotional appeal in a strategy referred to by some as “heartsounds.” Many such songs addressed listeners explicitly, as in Redington’s for McDonald’s.60 Talk of emotion was on the rise in the industry.61 Major campaigns with music that were launched following “You! You’re the One!” were the army’s “Be All You Can Be” (example 4.7, music by Jake Holmes); “Good to the Last Drop Feeling,” developed by Maxwell House with Ray Charles; and “We Bring Good Things to Life” for General Electric, by Thomas McFaul and David Lucas.62

With the triumph of the “heartsounds” strategy, composers began to have to be “chameleons with a feeling for the musical sound of a mood,” said one composer in 1976.63 A 1977 overview of the work of advertising composers noted that the composer had the difficult task of setting the mood in a commercial in a matter of seconds, which meant that composers had to possess varied musical backgrounds so that they could call upon different musics to evoke or support the mood in a commercial.64

Perhaps the quintessential heartsounds commercial actually employed a heartbeat-like sound in a mid- to late 1980s Chevrolet campaign called “Heartbeat of America.” Chevrolet’s advertising agency auditioned over a hundred songs before choosing one, by Robin Batteau, a songwriter and singer. Batteau wanted listeners to associate Chevrolet with the birth of rock ’n’ roll, and described the music as beginning with a folklike sound, moving to Motown, and then ending with rock (example 4.8).65 The music also employed synthesized heartbeat sounds. A New York City advertising music producer, who was not involved with this commercial, said that this music “has a wonderful sense of freedom; a fun quality that’s very loose, undisciplined; it sounds like real rock ’n’ roll instead of being contrived.”66 Advertising Age reported that consumers wanted to know where they could buy the music, and a record release was considered.67 Advertising Age wrote that the campaign identified the aspirations of Chevrolet with those of Americans instead of attempting to encourage viewers to identify with Chevrolet. The executive vice president–creative director for Chevrolet at the automaker’s advertising agency said that the mission statement for the campaign, forged in Ronald Reagan’s America during a period of increased nationalism, “demands that Chevrolet stand for America and for Americans, that it be the supplier of excitement and dreams for all of us who can’t afford Ferraris and Maseratis.”68

An article from 1981 discussed the rise of heartsounds and quoted several composers on the sound; one, Tom Dawes, who authored such music, said, “It’s a time for emotion. Tear-jerking stuff sells today. It’s not enough to just get consumers to understand in a commercial. They have to feel, too.” Another composer, Mike Uris, agreed. “You can tell, tell, tell viewers until you’re blue in the face,” he said, “but it doesn’t matter unless they’re touched. You can’t influence purchase decisions unless you touch the consumer—and I’m convinced that in a majority of cases, music ‘emotionalizes’ your selling proposition.”69

Music and Advertising in an Era of Heightened Consumption

The rise to dominance of the thirty-second commercial in the late 1960s meant there was less music scoring, but this didn’t hurt the jingle part of the business, for the increased federal regulation of advertising copy meant that music had to work harder in commercials. Strengthened restrictions on claims that could be made in advertising copy in this era meant that less could be said about products, putting more of a burden on music and other means of nonverbal communication.70

And it was inevitable that surveys about the use of music began to reflect the relatively new interest in emotion. A music production house conducted a survey of clients in the late 1970s and offered the results shown in table 4.1 to readers of Advertising Age.

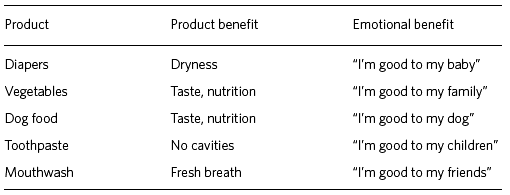

The rationalization of the benefits of using music for emotional purposes took many forms. A 1980 article included a little chart of the emotional benefits that music could produce with various household products (table 4.2).

In the early 1980s, perhaps as a result of the renewed emphasis on consumption in American culture, due in part to the efforts of Ronald Reagan and other conservatives to promote consumption as a necessity of citizenship, there was an uptick on questions of mood as a means to sell more goods. (I will discuss the rise of a new wave of consumption in the 1980s in chapter 7.) A 1982 article by the vice president and associate research director at Young and Rubicam shows the sophistication with which the topic of music and emotion was being discussed by people in the industry in this era, beginning by acknowledging the importance of music in commercials—“Music is the catalyst of advertising.” The author, Sidney Hecker, wrote that good jingles “have a clearly defined objective,” which he characterized as eliciting the appropriate feelings; good jingles “offer the listener a reward, in the sense of particular emotional feelings”; and “these executions clearly exemplify a brand personality.” Hecker’s article is all about the importance of music in imparting feelings to commercials: “Good composers can develop moods that range from dreamy, tender and soothing to bright, cheerful, joyous, to exciting and exhilarating, to triumphant, majestic, and even spiritual.” He continued, “Here is the power to move the listener, to turn him or her in a desired direction, to create empathy or rapport with our characters and with our brand, to augment or become part of the brand personality.”71

Table 4.1 What they think of commercial music, 1978

Music can create a strong emotional environment in which to deliver your message | 23.6% | |||||||||||||||||||

Music can emphasize visuals and copy points | 18.9% | |||||||||||||||||||

Each time your jingle is remembered, hummed or sung, a “free” advertising registration is made | 16.5% | |||||||||||||||||||

Because music can elicit an involuntary emotional response, it can help overcome a listener’s inclination to turn off the ad message | 15.1% | |||||||||||||||||||

By functioning as a sort of connective tissue, music can pull the spot together | 14.5% | |||||||||||||||||||

Music makes the message more palatable by entertaining the listener | 11.4% | |||||||||||||||||||

Source: Norm Richards, “Hints to Make Commercial Music Sing,” Advertising Age, 23 January 1978, 54.

Table 4.2 Emotional benefit added by music for various products

Source: Edward Vick and Hal Grant, “How to Sell with Music,” Art Direction, May 1980, 67.

Additionally, with the advent of the fifteen-second commercial in the mid-1980s, there was some discussion of using music for mood purposes rather than jingles, since the short period of time didn’t allow for a melody that could be developed. Suzanne Ciani, the renowned composer of electronic music in commercials, said that her way of dealing with the shorter commercials was to use music to aim always to express mood. Ciani saw her role in these sorts of commercials as “painting the sound.”72

The increased use of music was accompanied by an increase in its detractors, however; advertising legend David Ogilvy’s famous line—“If you have nothing to say, sing it”73—is mentioned in many trade press articles in this period, though most who defended the use of music referred to the changing landscape of the business. Composers understood their task in this era as attempting to inflect or create minor differences among parity products.74 This point was reinforced in another publication of the era, using the example of Burger King and McDonald’s. Since their products are much the same,

jingle writers . . . find themselves in the business of influencing trivial decisions: it simply makes no difference which hamburger one buys. One technique widely used to deal with this problem is to sell not the product, but various intangibles that can be associated with the product: sex, status, excitement, or Anita Bryant. Music has been found to be very effective in increasing these associations.”75

Table 4.3 Sample printout from the Soper MusicSelector software package, 1982

| MOOD: GRAND | STYLE: ORCHESTRAL |

| TIME: 3:00 | EXACT TIME: 3:03 |

| TEMPO: MED FST/160 | GROUP SIZE: LRG |

| INSTRU: RHY, STR, BRS, WNS, HRP, XYL, VIB, PER | |

| KEY SIGN: D | |

| TITLE: CORPORATE FANFARE | |

| COMMENTS: | |

| CAT NO: 42B-4 |

Source: Carol Deistler, “Tops with the Pops,” Audio-Visual Communications, March 1982, 24.

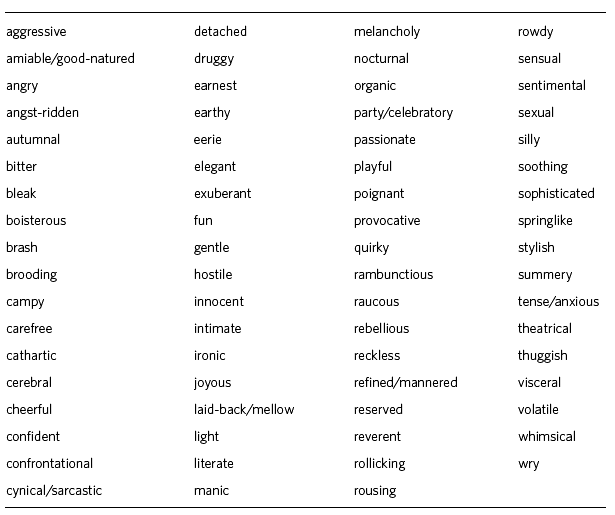

One way to acquire an understanding of just how important the question of mood had become by the 1980s is by examining library music, which is music composed to be stockpiled, waiting to be used commercially.76 Music libraries have long catalogued their music by mood, as well as style and other information. A 1982 article that discussed a computer soft ware application that allowed users to search for music in a database included a sample printout resulting from a search for a three-minute track with a “grand” mood by a large orchestra (table 4.3). Only one mood category is indexed here, even though the landscape of moods was increasing in this period.

Another sign of the increasing hold the idea of mood had on the commercial music industry was the rise in the 1980s of scholarly publications that explore connections between mood and music. With titles such as “Music, Mood, and Marketing,” and published in such periodicals as the Journal of Marketing and the Journal of Consumer Research, these articles are designed to aid advertisers and marketers. They are, from my perspective as an interpretive social scientist, much too scientistic to be of more than ethnographic interest, serving to point out how established the connection of music and mood had become in the advertising and marketing industry.77 One advertising textbook mined some of this literature on music and mood to produce a chart that simplistically links (for example) “sad” music to the minor mode, slow tempo, low in register, of “firm” rhythm (which is meaningless to musicians), consonant harmony, and of medium volume.78

Emotion as a Selling Point

By the 1980s, composers were routinely touting the emotional effects that they thought their music could deliver. “Music enables you to emotionalize your product and its benefits: your entire selling proposition. Through music, you are selling from the heart, to the heart,” wrote one commentator in the trade press in 1983, concluding, “Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast, and sell a lot of soft drinks.”79

The music and mood ideology became so influential that it began to infiltrate demographic considerations. A good example is recounted in a 1981 article concerning Bon Jour Jeans, an account belonging to Backer and Spiel-vogel. According to Bill Backer, “Blue jeans should be fun to wear, so a commercial for blue jeans should be fun to watch.” He thus worked to transform the image of the product from harsh “New Wave / punk” to soft “continental/ romantic” by using Jacques Brel–type love songs. “Our research indicated that this kind of musical approach could help build Bon Jour’s franchise most quickly,” Backer said.80

A few years later, Advertising Age began an article in late 1987 thus: “Emotion—defined as ‘any strong manifestation or disturbance of the conscious or unconscious mind’ (Encyclopaedia Britannica)—is what sells everything from diapers to diamonds in this country.” This preceded an interview and profile of composer/lyricist Joe Lubinsky of Hicklin Lubinsky Company or HLC Music in Hollywood. “Prime emotions are what make great advertising,” said Lubinsky, and, “great emotion works forever.” Lubinsky, like others in this period, began to speak in greater detail about how composers attempted to employ emotions in their commercials. “I have a tremendous concern that whatever I produce for my clients has some sort of emotional hook to it—something that will stay with the consumer. Emotional times are what you remember most in your life.”81

Music and Mood Today

Music and mood have become the main language by which people in music production companies and their clients in the advertising industry communicate, especially when clients aren’t familiar with musical terminology, which can be frustrating for musicians. As Fritz Doddy, creative director at Elias Arts in New York City, told me:

So we get together and figure out—my sad is your sad, and your blue is my blue, my fast is your fast . . . so we have some sort of understanding that, “Well we don’t want the spot to be melancholy, we want it to be bittersweet”—so we’re dealing in very subtle shades. “We want it to be a bossa nova, we want it to be a tango, we want it to be heavy metal”—so we define some very broad genre and mood parameters for a project.82

Again, the practices of library music composers shed light on the question of music and mood in advertising. An interview I had with such a composer, Andrew Knox, covered the question of mood in some detail. Library composers, perhaps even more than composers in music production houses, deal with questions of mood on a daily basis, for they not only compose music to fill niches in their libraries but they also write prose that describes their music so that it can be searched in vast databases.

Adjectives—they try to give me as many adjectives as possible, and most of the time they’re not musically inclined, and they don’t know what to say. “So, we want it to be more yellow, or more blue. . . . ” You have to start to learn the different adjectives that people use and then kind of interpret that into music. “Okay, I want something that’s simple and sad, but not over the top.” So maybe we go for an oboe kind of a sound rather than a violin, because a violin seems too sad-sounding. So maybe a light flute or solo piano might do that. So . . . you get to interpret, which is kind of fun for me to interpret their feelings, or their words, into music.

One of the skills a library composer must have, Knox told me, is to be able to describe music vividly in a single sentence. The goal is to characterize the tracks so pithily that they can appear in his company’s extremely sophisticated search engine.

The whole idea with these descriptions is to try to sell the client on actually listening to this track, ’cause once they listen to it, then they have their own idea. But . . . you have to figure out, “Okay, what can I say that talks about this piece of music but then also will let the client buy enough to even put it in the CD player?” The other thing that you think about when you’re describing your music is now, in the world of technology, . . . we have computer programs that you can search for music by descriptive words.

[Typing] “Sad,” “orchestral,” it’s like doing a Google search. . . . And, let’s see, 1,194 tracks came up with that. Now I’m sure there’s more than that many, I’m sure there’s more than that many, but those are all the ones that have “sad” “orchestral” in the description.83

The solution is what Knox calls the “shotgun,” whereby he provides a variety of selections and hopes that one fits the client’s needs.

Record labels similarly employ mood descriptors to classify their music to make it searchable by music supervisors, advertising agencies, and others for their use in broadcasting. In the mid-2000s, Sony Music offered a website called SonyMusicFinder to aid potential licensors of its music, offering seventy-one adjectives referring to affect (table 4.4). The sheer number of these terms as well as their subtlety provides a good example of just how refined this contemporary discourse of mood has become in the realm of commercial music today. It has to be—this is the primary means that consumers are interpellated as consumers, addressed by sounds at an emotional level that advertisers and ad agencies hope will encourage them to purchase goods.

Table 4.4 “Mood List” from SonyMusicFinder

Source: http://www.sonymusicfinder.com. This now-inactive URL was operational in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Since the late 1970s, the ideology of affect has become so deeply ingrained in the culture of the production of advertising music that composers routinely refer to music’s almost magical powers to influence consumers, speaking in matter-of-fact terms far from either Dichter’s psychologism or the scientism of later authors: this has become a central ideology that is repeatedly articulated by many in the field. For example, Phil Dusenberry, former chairman of BBDO, wrote in 2005, “Emotion is how a branding relationship begins.”84 Commercial music composers who have had occasion to write something about the efficacy of music in advertising nearly always refer to the idea that music will help consumers remember the product, even, or especially, at the point of purchase, and that the mechanism for this is emotion. One jingle composer wrote, “Music moves people emotionally . . . [and] hopefully puts them in a frame of mind to buy a specific product.”85 And another believed that music’s “messages sneak into our brains and cause us to act in certain ways. We buy products and services and may not even know why. We have been influenced by these creative messages and we respond often in spite of our better judgment.”86 A composer/owner of a music production company said in 1979:

Psychologists . . . tell us that most of our decisions are made on a subconscious, emotional level. . . . [Thus], we should be trying to reach [consumers] on those same emotional levels. If being easy to remember [“memorability” being a buzzword in this era] is a function of intellectual activity, it’s possible for the consumer to remember your commercial consciously, but not have it count as a factor in his emotional decision of whether to buy your product or service. . . .

And that, I firmly believe, is music’s main value as a marketing tool—its ability to cut through all the intellectual irrelevancies, and affect someone right in the gut, where brand preferences are often determined, and most buying decisions are made.87

In the fifty years since the advent of discourses about mood in music, it has been used, sometimes with great effectiveness, to support the postwar rise in consumption through the 1950s to its heightened importance in the 1980s, becoming indispensable in creating apparent differences between parity products, whether hamburgers or soft drinks. Coming in on the fashion for Freud in the 1950s, the use of music to create and manage mood in commercials has survived to the present, now with complex languages of affect—languages that can sometimes be vague and vexing for musicians dealing with nonmusicians. Today, not only is a language of affect dominant in the industry, it has its own rarefied and scientized language authored by academics and industry workers, which has continued to be employed during the Great Recession and afterward. The “magic of consumption” described by J. Walter Thompson in the 1950s is now driven in part by the emotionality of music.