Decline and Recovery

In 1861 and 1862 the Northern economy struggled as it coped with the shock of war. New Jersey and other states suffered because secession deprived them of their old customers in the new Confederacy.1 Midwestern farmers also had familiar economic patterns ruined by secession. They could no longer transport their wares down the Mississippi River, now running through the heart of the rebellion, a situation that limited access to markets and hurt the prices of their goods.2 Factories laid off employees and businesses failed. In Philadelphia workers unsuccessfully asked the city to initiate a public works jobs program.3

By 1863, however, wartime expenditures in supplying armies and the continued needs of the home market led to a boom that lasted through the rest of the war. Thus, Midwestern farmers rebounded and by 1863, an editorial writer for the Davenport Daily Gazette described “truly progressive” agronomists who experimented with diverse crops, concluding “The dawn of Iowa’s greatness as an agricultural state is breaking.”4 New Jersey recovered before 1863, even without access to Confederate cotton. Its factories were producing iron, rubber, woolens, and other items necessary for the war effort, sending the state on the road to prosperity.5 Nimble Philadelphia manufacturers deprived of Confederate cotton turned their textile machines to woolens while their counterparts in the iron industry moved into war production.6 New York City clothing and shoe manufacturers reaped profits from government contracts, sometimes wanting hundreds of thousands of uniforms or pairs of shoes in a single order, and the need for equipment spread the wealth to other businesses such as the Singer sewing machine company.7 Railroads, necessary for transporting all of these things, overcame early fears about the impact of the war, enjoyed an extraordinarily profitable year in 1863, and continued to do well for the remainder of the war.8

Such a rebound was visible among smaller businesses not directly connected with supplying the army as people who made money spent money. Karl Wesslau, a cabinetmaker in New York City, informed his German parents in December 1864, “last spring and summer business was very good.” By the end at the war, he assessed his situation and concluded: “At the beginning of the war we lost a lot of money, but in the last two years we’ve made up for our losses and more.”9 In early 1863, Catharine Taylor reported the evidence of renewed prosperity in Des Moines, Iowa. “W. Minson says that there are more buildings engauged [sic] to be done this summer in town than he knows of than has been done for the last two years,” she wrote to her soldier husband Taylor. “It seems as if money is plenty or more plenty at least than for some time back,” she continued, “for the Catholic[s] have got money and subscription to the amount of five thousand Dollars to build a new church.”10 But the money supply was a mixed blessing “because all manner of things have gone up.”11

Back East in New York City, German immigrant Emilie Wesslau, Karl’s sister, complained about the new wartime reality that accompanied the economic recovery. “Food prices have tripled, clothing has gone up even more,” she noted, “but we still haven’t suffered any want.”12 Emilie might have observed that things could have been much worse. She and other Northerners had to contend with a wartime inflation rate that was less than one-hundredth of that in the Confederacy.13

The sustained wartime recovery, although not enjoyed equally by all Northerners, generated a collective prosperity. The gross national product of the region was over $4 billion in 1864, which was more than the total for the whole United States in 1860, and R.G. Dunn and Company reported that only 510 businesses failed in 1864, well below the 5,935 failures in 1861.14 Millions of fresh acres came under the plow. Factories produced the necessaries of war. Immigrants arrived by the hundreds of thousands. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in army pay contributed to family economies. Railroads added over 4,000 miles of track. All of these things collectively added to the wealth of the loyal states as well as the federal treasury, leading President Lincoln to look to good prospects for a sustained war effort.15 On December 6, 1864, in his annual message to Congress, the president proclaimed that in every respect the nation was “gaining strength, and may, if need be, maintain the contest indefinitely” in terms of both men and material resources, which were “unexhausted, and as we believe, inexhaustible.”16

Agricultural Bounty

Wartime demand generally provided prosperous times for Northern farmers. Antebellum surpluses and then good wartime harvests combined with poor harvests in England and Europe boosted wheat farmers’ sales abroad. In 1860, Michigan exported over 1.9 million bushels of wheat to Great Britain. The very next year, it sent over 24.5 million bushels, peaking at over 27.3 million bushels in 1863 before declining to over 5.8 million bushels in 1865.17 From 1861 through 1864 the Union exported roughly 203 million bushels of wheat, worth $265 million. As one Midwestern editor proclaimed in late 1861, “Wheat is king and Wisconsin is the center of the Empire.”18 But at the same time, unprecedented English and European demand for other agricultural products further added to Northern farmers’ incomes, boosted the nation’s balance of payments, and compensated for the loss of Southern markets during the war. Such demand also tied England and France more tightly to Northern interests.19 American agriculture was already in a state of change, but increased demand required an expansion of acreage and settlement across the North, the wider use of machinery, and greater involvement of American farmers in an international market economy. Small farms remained the norm, but the scale of production was growing. So, too, was the size of debt, as farmers brought more land under cultivation and invested in new machinery thinking the boom years would last.20

Citizens who traveled in the agricultural regions of the North would have agreed with Lincoln’s assessment of the economic circumstances of their loyal states. Sidney George Fisher, for one, remarked as early as 1862 that in traveling across Pennsylvania he found that “Tokens of redundant prosperity & rapid improvement are visible everywhere” and that the “war indeed has revealed to us & to the world the immense power & unbounded resources of the nation.”21 In 1863, Mary Livermore also witnessed the agricultural bounty of the Midwest as she traveled by rail through parts of Wisconsin and Iowa that appeared to be “a continuous wheat-field.” “The yellow grain was waving everywhere,” she recalled, “and two-horse reapers were cutting it down in a wholesale fashion that would have astonished Eastern farmers.”22

Some lone females with husbands in the army and with a young son or two at home or perhaps a brother nearby to lend a hand survived or even prospered in this environment. Farms in fact might not miss a son of military age, since an older father handled the work and might be able to secure some assistance, even if from his younger children. In March 1863, Indianan Mary Hamilton, her two sisters, and her brother helped their father with the threshing of the wheat. It was not something Mary especially enjoyed since it meant putting off continuing her education but, she admitted, “I do not know what he would do if it was not for us girls.”23 Other families made sure that a son or a brother-in-law remained home to tend to the farm. Such was the case with the unmarried Gould brothers whose sister Hannah, the head of their parentless household, and her husband Marvin Thomas tended the homestead in central New York.24 In neighboring Ohio, 18-year-old Amos Evans, with older brothers in the army, temporarily took over from his politician father the family farm operations and the care of his mother and younger siblings. The responsibility was large, as would have been the case for most farmers in similar circumstances. He believed he had “almost enough to do for one of my years, yet I will endeavor to act my part, be my lot what it may.” Despite being “alone without help” and having “a rough time of it,” he trusted in God for success. In addition to the farm work, he also maintained a mill—still considered “the best in the Country”—and kept “up all our own repairs.”25

At the same time that agriculture demand meant prosperity for so many Northerners, there were small farms that remained beyond the reach of the rising market while others barely survived the war. Throughout the war, family-centric southern Indianans, for example, by choice retained their old-fashioned, low-effort, self-sufficient hog and corn farming, although they welcomed surpluses when they appeared.26 Other small farmers did not expect to continue to live on the margins but failed to achieve success. There were those farmers who took advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862 who did not persist long enough to register their claims. Also, there were hardscrabble marginal farms that sorely missed the labor of husbands or sons who went off to fight. Such was Anna Howard’s rugged, isolated homestead. Anna’s father had settled the family on “three hundred and sixty acres of land in the wilderness of northern Michigan” not close to much of anything. Ever the optimist, he was not averse to thinking he could eventually elevate his claim to the level of “a fine estate” that he could pass on to future generations of Howards. The war, however, interrupted such dreams and deprived Anna, her mother, and her younger siblings of the labor of her father and older brothers.27

The Howard family members did various jobs to bring in additional income “taking as boarders the workers in the logging camps, making quilts, which we sold, and losing no chance to earn a penny in any legitimate manner.” Anna’s mother also did sewing, “yet every month of our effort the gulf between our income and our expenses grew wider, and the price of bare necessities of exis[t]ence climbed up and up.” The wartime home front made an impression on the young girl, and she later recalled, “It was an incessant struggle to keep our land, pay our taxes, and to live.” Labor was in short supply, thus “There were no men left to grind our corn, to get in our crops, or to care for our live stock [sic]; and all around us we saw our struggle reflected in the lives of our neighbors.”

Anna long remembered an existence that was a “strenuous and tragic affair.” “The work in our community, if it were done at all,” she later wrote, “was done by despairing women whose hearts were with their men.”28 The Howards survived, but less fortunate families in similar circumstances struggled. Lucy Wheat lost the family farm in Illinois when her husband died and her son left for the army. Wartime inflation compounded her money problems. She complained that the war had brought only “cair, anxiety & trials” and feared that she might have to resort to prostitution to save herself.29

Manpower on the Farm

As Anna Howard witnessed, the high level of soldier recruitment from the rural North made it more difficult to meet agricultural demand, leaving many farms short of labor during the war.30 The Old Northwest states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, for example, had to continue to keep farms productive while sending to war about 680,000 men who served for more than a short term; on average, every other farm family in those states made due without a worker because of the demands of the military.31 Back East in New Jersey, where a private’s pay beat by one dollar the workingman’s monthly wage of $12, employers lost access to 74,000 volunteers.32 The Gardner, Kansas, area, a farming community on the Missouri border, was doubly troubled. Laborers not only joined the army, but employers also lost “our itinerant population all driven back in the interior for safety” because of the fear of additional raids from their proslavery neighbors.33

Thus in August 1863 immigrant German farmer Dietrich Gerstein reported to his brother from his backwoods Michigan farm, “Almost all the single men who work full-time for other people are gone, and the married farmers either don’t work for wages or ask for wages that no one can possibly pay.”34 The situation in Gardner, as W. M. Shean, a letter writer to the Kansas Farmer, noted in January 1864, was equally difficult, since it was “impossible to obtain a day’s labor at any price.” As a result, “improved land lies idle from scarcity of labor.” Shean urged the state to encourage immigration, which would repay government efforts with farms restored to productivity, “add[ing] to the wealth of the State.”35

By 1863 the government helped ease the labor shortage with a generous immigration policy. German, Swedish, and Norwegian immigrants started up farms or hired on as farm laborers, pulled westward from eastern port cities by the promise of land made by the government in the Homestead Act and by railroad companies offering credit to draw settlers along their lines.36 Perhaps an encouraging letter home was sufficient to prompt such emigration to a new land. In May 1864, Karl Wesslau wrote to his parents and siblings, explaining, “These are very good times for people in Germany who want to come over here, [because] it’s easy enough to find well-paid employment.” Furthermore, assuring them that noncitizen immigrants could avoid military service, he explained, “The government does all it can to encourage immigration, since the war has already cost so many lives that there’s a shortage of men.”37 Indeed, in Ireland persistent hard times encouraged emigration, with young men even prepared to serve in the army for ocean passage, a bargain that would have eased labor problems as it eased recruiting demands. The potential emigrants found an advocate in the U.S. vice-consul in Dublin.38 Despite efforts of foreign governments to discourage emigration, roughly 800,000 immigrants, mostly young northern and western European men, flocked to the Union by the end of 1865.39

The farm laborers benefited to a degree from the wartime agricultural expansion and labor shortages, although landowners did better. As Dietrich Gerstein observed, “For laborers here, in fact, times have never been better than they are now.”40 Antebellum Ohio hands had received a yearly wage upward to $150 in addition to their keep; during the war their wages rose to a high of $250 dollars in addition to their living.41 In 1864, New Hampshire farmers paid female field workers a daily wage of $2 in addition to their board.42 The proximity of New York farms to the bountiful Midwestern acres and their higher wages forced landowners to pay more than they wished to keep their hands 43

To ease the labor shortfall, Northern farmers continued to make use of technology, since machines had already shown their promise before the war. Such machinery proved especially useful on the cereal-growing prairies and plains where reapers and mowers repaid the investment with greater efficiency and a reduction in the manual work force. As the Minnesota Farmer boasted after assessing the abundant 1861 wheat harvest, “the addition of one thousand reapers to the already large cutting force, has materially helped to make harvest comparatively easy and of short duration.”44 Investing in a machine also provided some farmers with additional income and a new type of employment, as they traveled their neighborhoods working other farms for a fee. “It is thus,” wrote a Cincinnati editorialist in 1862, “that machinery has done the work of thousands of men, who have thus been spared for the war.”45 Between the start and the end of the war, the number of factories producing the needed machines increased significantly, adding weight to the farmers’ arguments about agriculture being at the heart of the nation’s economy. Before the start of the war, there had been over 70 factories in operation; in 1864, there were 187 works making reapers and mowers and keeping 60,000 employees busy.46

The spread of technology allowed farmers’ daughters to step into the shoes of brothers who went off to war. Young women wrangling a team of horses attached to a machine to prepare fields for planting or to harvest crops became common sights in Ohio and elsewhere.47 As Mary Livermore’s Midwestern women discovered, the work that they performed in planting, tending, and harvesting crops when their men were away was difficult but manageable, especially with the aid of farm machinery. The work demanded new skills, and the necessity of it forced women to learn them or the farms would fail. Some women took pride in their work. Indeed, one woman boasted that she could do it all and match any man in working a binder.48

Women also saw their work as a patriotic duty. The country needed them to take on new roles. For Livermore, these women “were invested with a new and heroic interest, and each hard-handed, brown, toiling woman was a heroine.”49 Conservative Northerners did not always see it that way and protested such activity, fearing it would somehow debilitate feminine minds and bodies.50 The editor of the Prairie Farmer disagreed, assuring farmer fathers that such work would “not compromise . . . [the] dignity and sense of propriety” of their daughters, while the Illinois State Agricultural Committee urged women to put aside their feminine attire and go into the fields to drive the various machines they could easily handle.51 In fact, farmers’ daughters and patriotism could sell farm equipment, or so one manufacturer believed when he advertised in the June 10, 1865, issue of the Prairie Farmer. The illustration depicted a respectable looking young woman, protecting her complexion with a broad brimmed hat, in charge of a “Sulky Hay Rake.” The character explained her actions by noting her “brother has gone to war.”52

Although labor shortages and other difficulties caused many farmers to struggle if not fail, discipline, luck, and rising farm prices brought personal rewards, kept farms in business, and fueled expansion. Ovid Butler, president of a college in Indianapolis, for example, invested in cheap farmland in Illinois, which allowed him to reap a fine grain harvest in 1864, despite the burden he had of managing the property on his own. It was not only a way to make money, he explained to his soldier son Scot. “I feel that in these times while so much of the labor of this country is necessarily withdrawn to fill the Armies” it became a patriotic duty “to increase those productions of the earth which are essential to feed and clothe these Armies and the population.” Such a person was, in fact, “a public benefactor.”53 Persistence, opportunity, and examples of success, as well as Ovid Butler’s style of patriotism, encouraged the establishment of new farms and the expansion of old ones, even in New York State.54

Industry and Labor

The demands for farm equipment meant that manufacturers had to increase their production, the requirement of which placed them in labor situations similar to the farmers who purchased their products.55 Nonagricultural workers such as those men laboring in the farm machinery factories made up an increasingly large segment of the Northern economy by 1860 and grew in size because of the war. They included all sorts of skilled workers and tradesmen necessary in a diverse and vibrant economy and usually spent their time in small shops and mills rather than large factories.56 Specialized industries blossomed, such as the textile mill in Philadelphia that developed a reputation for “the superiority of its mourning goods.”57

Industry and transportation joined agriculture in coping with the patriotic enthusiasm of their workforce, especially in the first years of the war. In September 1862, Massachusetts tanner Henry Fowler complained, “Labour is very scarce,” the consequence being “I have to do all my work alone which makes a slow job of it.” Because of this scarcity, he noted, “Shoe makers are getting better pay than they have had before for years.”58 He was not alone in his predicament. Benjamin Hirst, his Rockville, Connecticut, coworkers, and workers throughout the North left the mills and mines with fewer hands as they answered the call to arms.59 Fledgling trade unions also suffered, their ranks diminished as their members enlisted, some not to return, while some local organizations disappeared from the record.60 Even the coal mining area of eastern Pennsylvania sent off Democrats and Republicans, especially from among the Welsh, Irish, and other immigrant populations, to answer Lincoln’s first call; it was a display of bipartisan unity that would not outlast emancipation.61

Railroad companies struggled to employ enough men to keep the trains on the tracks. In 1863 foremen for the Western Railroad in Massachusetts complained that the company had lost so many men that they could not unload the coal cars, and the Chicago & Alton Railroad stopped service for a time because it had no mechanics to do repairs. The railroad companies countered the appeals of the military by raising pay, getting employees draft exemptions, and matching army recruiting bounties to attract and retain workers, with mixed results.62 In some places, such as New Jersey, the loss of skilled workers provided opportunities for men and boys not yet masters of their crafts to move up the economic ladder.63 Consequently, craftsmen were at an advantage in such a market, but laborers benefited as well. When Karl Wesslau encouraged home folks in Germany to emigrate, he reported, “At the moment there are opportunities to earn money like never before” because “these are golden times for craftsmen, workers and soldiers.” He estimated, “a laborer can support his family on 4 days of work a week,” although the challenges of inflation remained real.64

The labor demand continued through the war, despite immigration, and necessity meant employers turned to women and children to help fill their needs. Owners of textile mills, shoe factories, and other businesses used to female labor hired more women and children to the point where their numbers among the North’s mill and factory employees increased by 40 percent.65 The expanding wartime management needs of governments and many businesses also meant an increase in office staffs to handle the information, complete and process all manner of forms, file reports and myriad other documents, manage payrolls, and perform a host of other bureaucratic duties. Women stepped up to fill these needs, but not without being reminded of their economic inferiority by their lower wages.66

The women who replaced men as clerks in shops or hired on as office workers in expanding government bureaucracies became the public faces of the feminization of work, something more conservative Northerners found objectionable. In July 1862, German emigrant Johann Diedan noted a shift in Chicago stores because of the war. “Up to now in America it hasn’t been the custom to have ladies as store clerks,” he wrote to a cousin in July 1862, “but now several merchants have hired young ladies instead of young men who are going to war.” His employer planned to hire as many as seven if he “can find the right ones.”67 In Dubuque, Iowa, Florence Healy took on a position as a shop clerk to fill a gap left by the war. Some customers threatened to stop shopping at the store, but Healy’s employer endured the challenge with no financial harm to his business.68 By February 1864, Chicago merchants who resorted to using female sales clerks were pleased with “the uniform tact and integrity of the women employed”; an editorialist expressed hope that the practice would continue.69 In fact, there were editorialists who saw Healy and other women taking on similar positions as being true patriots. They censured the men who held such “light avocations” when they should be in the army and when there were women perfectly capable of taking their places.70

Beyond those “light avocations,” women as well as children took up positions in manufacturing, including those businesses that produced war-related products such as armaments. They worked cheaply, under poor conditions, and for long hours. In urban areas, they stretched their budgets as best they could, but on occasion some of them supplemented their income with prostitution.71 All factory work could be dangerous, even in textile mills and clothing manufacturers, but women and children did obviously hazardous work in munitions manufacturing plants, arsenals, and other military facilities. Two horrific accidents occurred exemplifying the dangers involved in serving the needs of war. On September 17, 1862, an explosion and fire at the U.S. Army Arsenal at Allegheny, Pennsylvania, took a severe toll on women workers there, while on June 17, 1864, a similar deadly accident occurred at the Washington, D.C., Arsenal. On June 20, crowds gathered to pay homage to the Washington arsenal workers at a large funeral procession, which included President Lincoln, and the press called for an investigation of conditions in the government-run plants. Significantly, such accidents, whatever the public acknowledgment of them, did not improve working conditions or women’s pay. Nor did they discourage women from seeking employment in such facilities, for the hiring continued throughout the war.72

The demand for labor helped workers, but workers, pressed by inflation, did not enjoy their fair share of the benefits of the growing economy. The rift between capital and labor started to become apparent. Workers protested low pay, poor working conditions, lack of respect, and other discouragements. Women were as aggressive as men in demanding pay increases and improvements. They had some success in military factories. Ordnance workers at the Allegheny Arsenal in Pennsylvania and cartridge makers at the Watertown Arsenal in Massachusetts protested layoffs and work conditions and got some concessions, and respect, for their efforts.73 From 1863 to 1865 seamstresses in several cities threatened work stoppages and made public appeals for support for relief from poor conditions and low pay. They drafted petitions and memorials to Congress, President Lincoln, and Secretary of War Stanton emphasizing their patriotic sacrifices. In 1865 a group of Cincinnati seamstresses, for example, asked Lincoln for fairness as “the wives, widows, sisters, and friends of the soldiers . . . depending upon our own labor for bread [and]. . . . in no way actuating by a spirit of faction, but desirous of aiding the best government on earth, and at the same time securing justice to the humble worker.”74 Such appeals largely failed, and women in certain industries in New York and Philadelphia began to organize.75

Other laborers showed their displeasure with their economic situation by organizing and striking. During 1863, trade unions exhibited a new militancy, striking in Boston and elsewhere.76 In some areas, such as New York City and the mining regions of eastern Pennsylvania, workers’ displeasure combined with antiwar sentiment spilled over into draft resistance, violence, and bloodshed.77

Integrating the Market

Building on developments started before the war, the North improved its transportation and communication networks, facilitating the growth of an integrated national market. Great Lakes shipping grew during the war to meet the increased demands of moving grain, meat, and lumber to markets, and also kept down railroad rates by offering a cheap alternative. Railroad companies improved their capabilities by upgrading lines, standardizing signaling systems, developing uniform freight-handling procedures, and building connections to link existing lines. Managerial and office efficiencies also improved carrying capacity and delivery. In response to government and market-driven pressures to cut costs and improve performance, the Pennsylvania Railroad completed the first trunk line between Lake Michigan and the East Coast by buying up the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, and Chicago Railroad and linking it with its existing system. Creating railroad systems through the acquisition and linking of existing lines became the dominant pattern of railroad development east of the Mississippi after the war.78

Further binding markets, and thus the North, together was the continued development of commodity exchanges and wholesalers, helping to further the war’s aims by connecting Eastern cities and producers with Midwestern markets, thereby integrating the states into a commercial nexus.79 As Abraham Lincoln understood, “the United States is well adapted to be the home of one national family,” not two or more, as he noted in December 1862, and its “vast extent, and its variety of climate and productions, are of advantage, in this age, for one people . . . [because] Steam, telegraphs and intelligence, have brought these, to be an advantageous combination, for one united people.”80

The commercial benefits of these connections as well as the war’s needs were important not only for farm and factory, but for the development of the urban hubs of commerce for counties and regions as well as the nation. In Rockland, Maine, William S. Cochran had a sail-making business, but shifted his attention to army tents thanks to a government contract at a critical time when the town was suffering from the loss of its Southern lime market. Cochran’s business was able to offer new opportunities for unemployed workers, eventually having 500 people on the payroll producing 100 tents a day, totaling 6,000 by the end of the war.81 As early as November 1861, the benefits to Rockland were apparent. The editor of the Democrat and Free Press reported on the impact to the town of having a thriving business within its bounds. “Our streets are filled morning, noon and night with men and women whom he [William S. Cochran] employs,” he wrote, “and the wages which they make are equal to the wages of the best of times.” The benefits rippled through the seacoast town, where “The needy are not only making a handsome living from the General’s business, but our public houses, dry goods dealers, grocers, market shops, and in fact persons in al [sic] kinds of business are reaping the benefits of it.” Rockland, he concluded, should be grateful to Cochran for this work, and he will be “kindly remembered as long as the recollection of this rebellion exists.”82

On a much larger scale, Chicago became the great engine and beneficiary of the east–west connection generated by the war effort. In 1861 it was already the western terminus with three railroads connecting the Midwest with the East and other lines fanning out to the farmlands of the prairies. It also had the advantage of being a major port. Its large grain elevators, lumberyards, stockyards, and slaughterhouses attested to its increasingly central place in gathering and processing nature’s produce. Its grain and lumber exchanges dominated the markets and brought order to trade by centralizing information flows, providing credit, reducing risk, and promoting planning. During the war, Chicago capitalized on its advantages to meet the Union army’s voracious demand for meat and in the process displaced Cincinnati as the world’s largest meat-packer. In 1864 Chicago pork packers and railroad executives laid plans for the massive Union Stock Yard that would further transform the meat trade.83 The unintended consequence of this growth was a foul urban water supply that eventually required new infrastructure investment.84

Profit Makers

If workers could not claim fair shares in the growing Northern wartime economy, their travails certainly helped businessmen, who paid off debts, built up cash reserves, and invested in expansion and improvements. The war thus hastened the shift from relying on credit from merchants to securing capital from profits and from banks.85

It also led to greater cooperation between business and government. By late 1861, for example, the Army’s Quartermaster’s Bureau stepped in to bring order to military procurement and to contract with suppliers on the basis of competency rather than political patronage. The result was more systematic government oversight of production by specifying requirements for the quality and durability of cloth, shoes, and other goods demanded in government contracts.86 The government’s requirements continued to play a major role in wartime economic growth. As one Massachusetts writer noted in August 1863, “In every department of labor the government has been, directly or indirectly, the chief employer and paymaster.” 87 This, contracts for moving men and freight provided the impetus for the development of William Davidson’s river-based transportation monopoly. Political connections and wartime contracts allowed William Drew Washburn to profit from the state’s vast lumber resources. The success of the businessmen of St. Paul and Minneapolis led to the recapitalization of the state’s foundering railroads and the landing of additional government contracts. 88Over the course of the war, the federal government spent about $1.8 billion, much of it directed to those businesses that could provide the necessities of a fighting army. 89

Such expenditures stimulated innovative products. In 1864, the Patent Office issued over 5,000 patents, which was more than any previous year for the whole United States. Most of the new wartime inventions were geared to the domestic market, but many also had military uses. Thus inventions such as washing machines, clothes dryers, rubber wringers, coal-oil lamps, feed bags for horses, improved sewing machines, steam dredges, and stone-cutting machines served both the home front and the armies.90 Other businessmen benefited from federal spending by expanding their antebellum products, now in demand because of the war. In 1856 Gail Borden had patented a process for producing condensed or concentrated milk. In 1861 he began large-scale production in New York, and by war’s end he had improved the process and expanded production dramatically by establishing branch factories and licensing other producers to meet demand. When sealed in cans, concentrated milk was ready-made for shipping long distances without spoiling, making it valuable in supplying troops in the camps and citizens in the cities. The success of condensed milk also encouraged Borden, and others, to experiment with the condensation process for other foods.91

Ordinary Northerners might consider it acceptable for these businessmen to make a fair profit, but avarice was bad for the economic life of the nation, not to mention the lives of its soldiers. More disconcerting for some civilians and soldiers were the moral implications of rapacious businessmen taking advantage of a witless government as they steered the country toward the notion of equating national strength with the unfettered, free-wheeling capitalism that became common after the war. Some of these selfish businessmen even proudly asserted that only a fool would join the army when so much money could be made at home. Banker Thomas Mellon, for example, wrote his son that rather than enlist he should understand that “a man may be a patriot without risking his own life.” After all, he reasoned, “There are plenty of other lives less valuable or ready to serve for the love of serving.”92 Many of the nation’s financiers agreed, including those among New York City’s elite.93

During the war, however, thoughtful Yankees considered this problem to be more than making unfair profits. Rather, greed could very well be a sign of moral decay or corruption that could threaten the prospects of victory and the very soul of the Republic.94 One of the by-products of wartime profits was the creation of what the New York Herald called “The Age of Shoddy,” a neutral term first used to describe inexpensive, inferior cloth that became a disparaging word for substandard goods and lack of patriotism in general.95 “The lavish profusion in which the old Southern cotton aristocracy used to indulge is completely eclipsed by the dash, parade and magnificence of the new Northern shoddy aristocracy of this period,” the editorialist observed in August 1863; “The individual who makes the most money—no matter how—and spends the most money—no matter for what—is considered the greatest man.”96 Thus, the hardworking German craftsman Julius Wesslau observed a year later the extravagance and spectacle described in the Herald in New York City, where “The main streets are clogged with fine and glittering ladies and gentlemen.” “So while in the field in the South the most horrible war is raging,” he pointed out with a degree of irony, “here in Neujork [sic] it’s one good time after another, at balls, the opera, theaters and other places.”97

Such a class of conspicuously consuming profiteers irritated those less fortunate Northerners who believed the capitalists’ self-absorbed desire to increase their wealth could damage not only their own character, but also that of the nation. Northerners might have exaggerated the numbers of these crass, newly enriched businessmen of the shoddy aristocracy, but the sense that there were men profiting from the war, dragging it out beyond reason, and caring more for money than patriotism troubled them. Philadelphia teacher Carl Hermanns believed Northern forces could handily defeat the Confederacy, “But the men who are at the top and who collect all the millions don’t want to turn their men loose, and they are dragging the war out like a lawyer does a court case.” He vowed he would not fight “for these cheats and politicians.”98

Hermanns exaggerated the control the big men of the North had over the progress of the war and their collusion in its delay, as well as the consequences of their bad decision making, but people did notice a greediness abroad in the land. Philadelphian Sidney Fisher expressed his disgust with an acquaintance who had “lost character since the war began” and worried more about his investments than the future of the Union. “Other people, as much accustomed to comfort and entitled to it as he,” Fisher judged, “have lost everything or are subjected to severe privation and yet are ashamed to make a complaint.” For Fisher, the war tested character and his friend so far had failed the test.99

Even soldiers noticed this desire to profit as they moved through the North on their way to defend the nation at the front. The dismayed Indianan volunteer George Squier wrote from Indianapolis after observing all the signs that showed “money is the order of the day.” It was hard for him to witness, this “low dispisable [sic] cunning used to gain position and position” even as people cheated the government and the selfless volunteer. Near despair, he admitted that he had to “clench my hands to prevent my patriotism from coming out the ends of my fingers.”100

Such actions could not go unpunished and would have serious ramifications. The Reverend James Remley feared that God would destroy such selfish men and the selfish nation they were making. In November 1862, he complained to his son Lycurgus, now serving in the army, about the “Thousands of private citizens” who were “even now speculating in the public misery and trying to make money out of the blood and dying groans of innocent people.” Furthermore, he worried the war was “being prolonged on purpose to give more time to these traders in human wars to carry on their fiendish business.” “How much of this,” he lamented, “the Almighty will suffer before he destroys a nation I cannot tell.”101

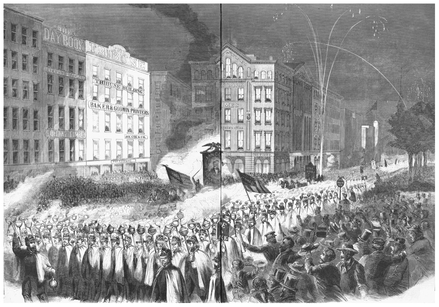

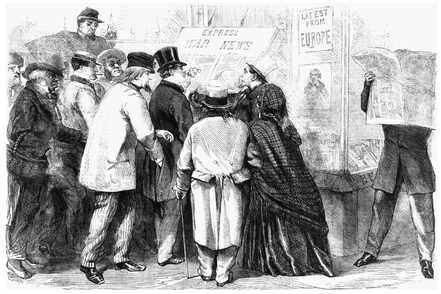

Reading war news in Broadway, New York. During the war, people frequently gathered in public spaces to read extra editions as well as regular editions of their favorite newspapers, a practice that facilitated discussion and debate. (Library of Congress)

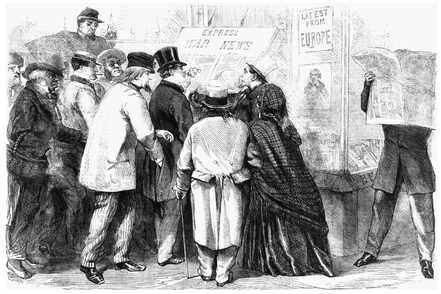

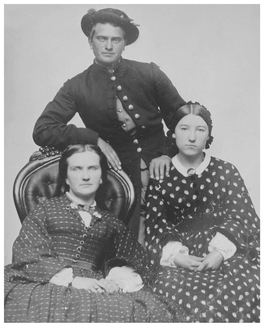

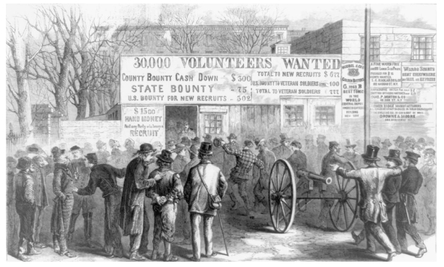

Recruiting for war: scene at the recruiting tents in the park, New York. Parks in New York City, Brooklyn, and elsewhere became sites of recruiting efforts, changing public landscapes from places of leisure to places of war. Other public spaces would soon give way to campsites and barracks for the new recruits. (Library of Congress)

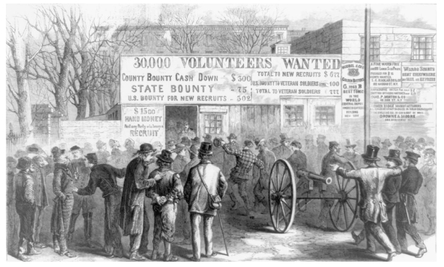

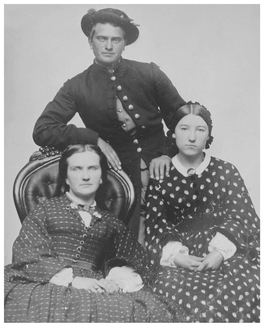

Unidentified soldier in Union uniform and two women. This picture of a soon-to-be separated family probably depicts a recruit with his mother and sister. When soldiers volunteered, they left behind families that would feel their absence and anxiously pray for their safe return. Such images, often made before soldiers left for the war, were popular ways to preserve visual reminders of absent loved ones. (Library of Congress)

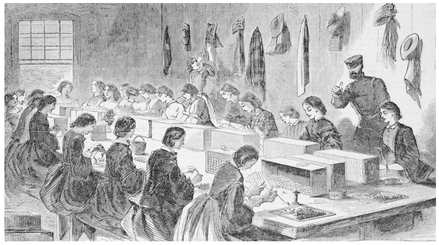

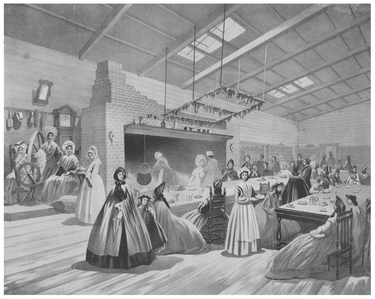

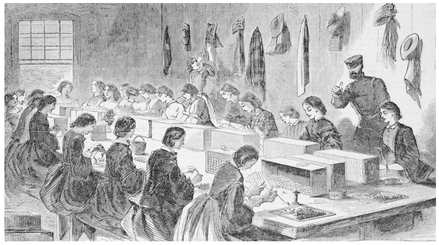

Filling cartridges at the United States Arsenal at Watertown, Massachusetts. The industrial capacity of the Northern states provided a great advantage to the Union war effort. The Watertown arsenal was not unusual in relying on women workers to maintain production as men left for war. The image, from the July 20, 1861 cover of Harper’s Weekly, was also a reminder of what women could do for the war effort. (Library of Congress)

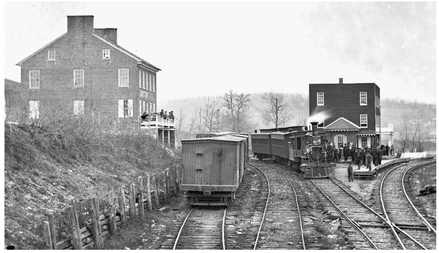

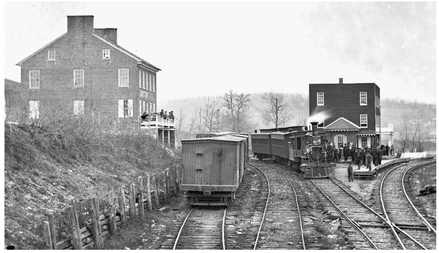

Station at Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania, 11/1863 (or 1864). Railroad engines, rolling stock, and facilities such as those at Hanover Junction allowed the Northern states’ industrial and agricultural output to reach the men in the Union armies as well as civilians on the home front. (National Archives)

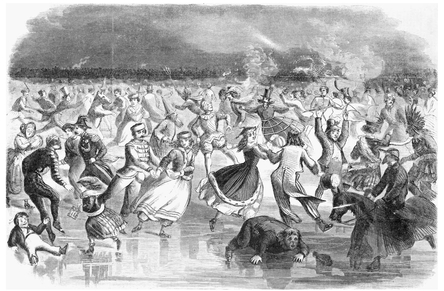

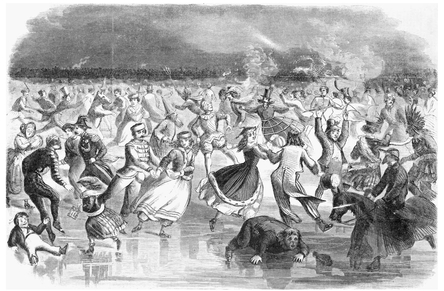

Skating carnival in Brooklyn, February 10, 1862. Northern civilians escaped the worries of war amusing themselves as they could, in this case by skating, a popular winter pastime. (Library of Congress)

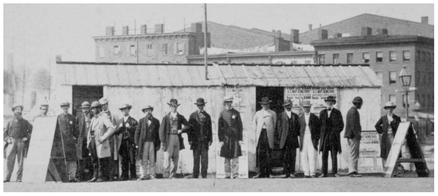

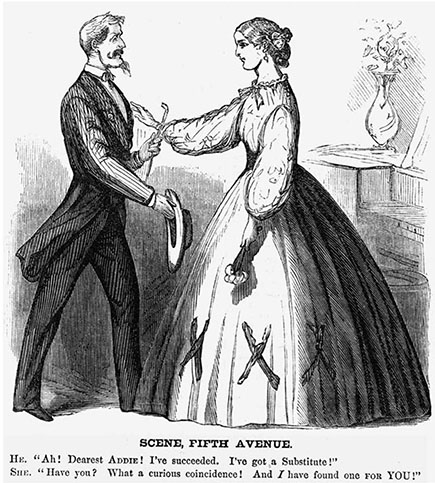

Bounty brokers looking for substitutes. With the arrival of conscription came the practice of allowing individuals, including wealthy men such as Theodore Roosevelt Sr. of New York, to hire substitutes to replace them in the army. (Library of Congress)

Secretary Chase’s March and Quickstep. During the war, composers produced music to commemorate all sorts of occasions and to honor various celebrities. They especially sang praises for the flag and the girls soldiers left behind. They also composed at least a few songs about the country’s new paper money authorized in 1862 and commonly called greenbacks. (Library of Congress)

The Story of Gettysburg. Music composed for piano and respectfully dedicated to H. T. Helmbold, chemist. The cover illustration of this song in commemoration of the victorious battle at Gettysburg also illustrates how many civilians came to learn about the experience of battle. (Library of Congress)

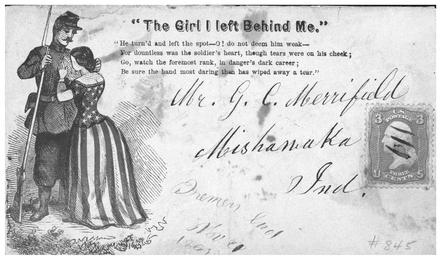

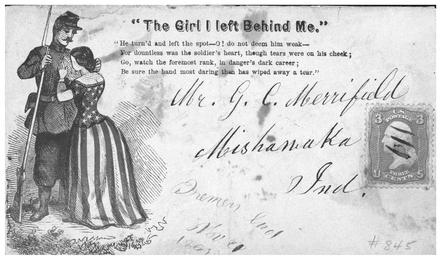

Civil War envelopes. During the war the federal mails carried a significantly increased volume of letters between civilians and soldiers. The patriotically decorated envelopes were one means by which correspondents conveyed support for the war effort. (Library of Congress)

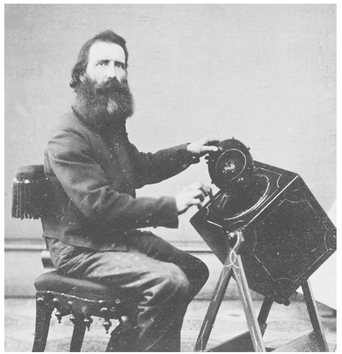

Civil War induction officer with lottery box. The U.S. government responded to the slowing of volunteers and the continued need for soldiers with the Enrollment Act of 1863. A man known to the community drew names from a wheeled or tumbling box, which led some anti-war Northerners to refer to the contraption as the wheel of death. (Library of Congress)

Scene Fifth Ave. Social pressure could play a role in encouraging men to do their duty. (Library of Congress)

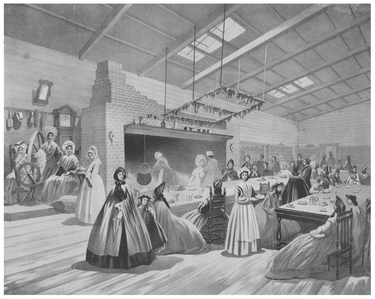

Brooklyn sanitary fair, 1864. New England kitchen. Northerners found purposeful amusement in attending sanitary fairs that appeared in cities from New York and Philadelphia westward to St. Paul, Minnesota. Women carried a heavy burden in organizing the fairs, which raised funds for the relief of soldiers and their widows and orphans. The large fair buildings had various departments displaying art, agricultural tools, and other examples of Northern ingenuity as well as relics from battles and extraordinary animals, such as Old Abe, the bald eagle mascot of the Eighth Wisconsin, exhibited at the second Chicago fair along with a large ox named General Grant. (Library of Congress)

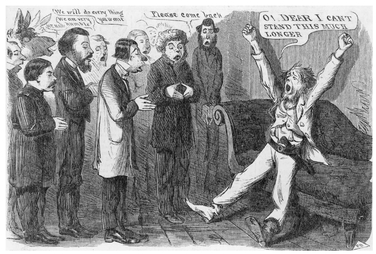

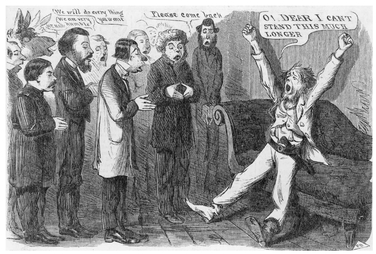

The copperhead plan for subjugating the South. The cartoon mocks the Copperhead or Antiwar Democrats and their desire to avoid further bloodshed and talk the Confederacy into peace terms. (Library of Congress)

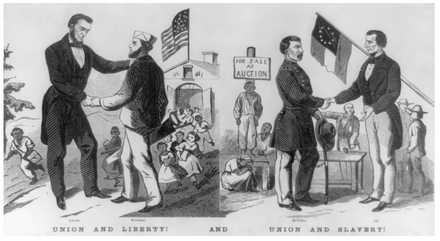

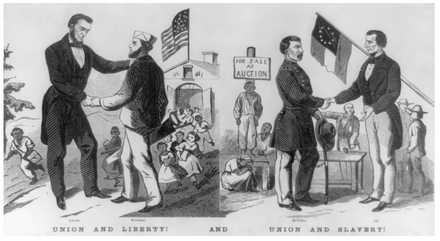

Union and liberty! And Union and slavery! During the presidential campaign of 1864, the Republicans stressed their patriotism and associated it with the virtues of free-labor society, while denying any patriotic motive to their opponents and accusing them of being willing to accept reunion with slaveholders. (Library of Congress)

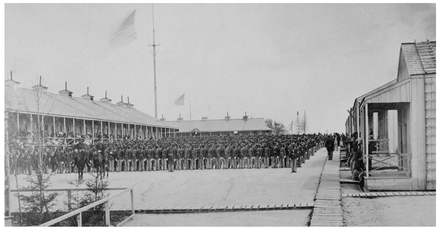

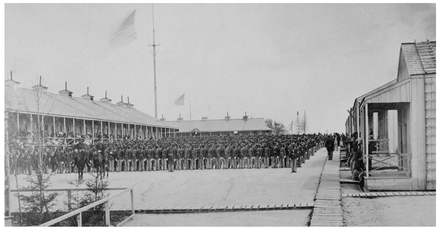

The 26th U.S. Colored Volunteer Infantry on parade, Camp William Penn, Pennsylvania, 1865. In June 1863, the United States Army established Camp William Penn for training units of the United States Colored Troops. The photograph also shows a neatly constructed rendezvous camp, something that became more common as the war progressed as stables on fairgrounds gave way to purpose-built barracks for sheltering recruits. (National Archives)

Arch at Twelfth S., Chicago, President Abraham Lincoln’s hearse and young ladies. Lincoln’s funeral train passed through Northern cities, stopping to allow citizens to mourn the loss of their president, as it brought the president’s body to Springfield, Illinois. (Library of Congress)

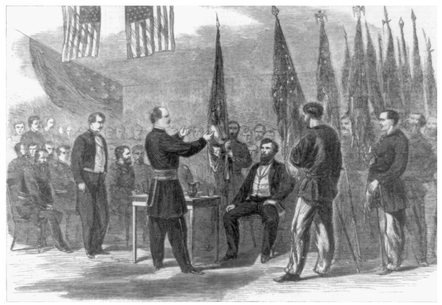

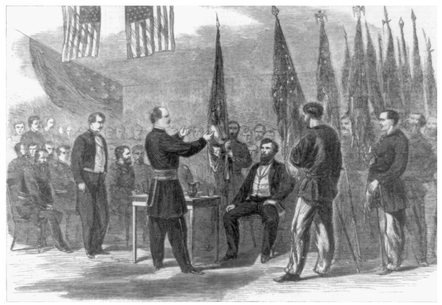

Presentation of two hundred battle-flags to Governor Fenton at Albany, New York, July 4, 1865. At the end of the war, one of the last acts of many regiments was to return their battle flags to their states’ governors along with the captured flags of the enemy. (Library of Congress)