One of the turning points in my life occurred when I was in college. My crop science professor, Stan Ehler, told me to stop by his office sometime when I had a chance. I took a moment to do so, and when I walked in, he handed me a well-worn copy of a magazine called The New Farm, published by the Rodale Institute, that discussed regenerative agriculture — instead of the high-input farming practices then in vogue, the focus of most farm magazines then and now. He told me he thought I was the only student in his class who might appreciate the message in this magazine, and he gave me the copy to read.

There were articles on cover crops, rotational grazing, and other low-input agriculture practices. But the most impressive article in that magazine was an excerpt from the book Tree Crops by J. Russell Smith. I was so enthralled by the article that I went to the college library the next day and was fortunate enough to find the book. I checked it out and read it cover to cover that evening, and to this day I read it again probably once a year.

Smith was a geographer who traveled the world and saw how agriculture systems affected the land and the people who depended on it for survival. He found that the most prosperous areas were the ones that relied on perennial crops such as pastures and trees, while the ones that relied on annual crops eventually destroyed their soil, and thus destroyed their prosperity and their means of life. He also noted with alarm that even though the soils of the New World had been farmed for only a century or two, they were being destroyed at a rate faster than that in any other civilization in history.

Felled trees can be a valuable source of feed, as this cow eating a mulberry tree would agree.

He suggested a system of agriculture in which trees were used to produce not just human food, but also the concentrate foods for livestock, instead of using annual crops such as corn and soybeans to feed our livestock. Livestock could be used to gather fruits, nuts, and browse from pastures with trees planted at low density, sort of a man-made savannah, with minimal need for expensive inputs such as fuel, fertilizer, machinery, agrochemicals, or labor. Smith carefully measured yields of carbohydrates and protein from these tree-plus-forage systems and found that they were comparable to the yields of annual crops in that day.

Obviously, Smith’s message went unheeded by mainstream agriculture. But it has had a profound influence on my thought processes ever since. Smith was succeeded in these pioneering efforts by Bill Mollison from Tasmania, who developed the concept of permaculture, a discipline that has grown slowly ever since and is now practiced by numerous people, although mostly on a small scale. If you have never read Tree Crops, or Mollison’s Permaculture, I strongly suggest you do so.

The system of agriculture espoused by Smith has become known today as silvopasture, the practice of growing trees and pastured herbaceous plants together. Silvopasture is not the simple act of letting animals run free through a forest to gather what they may. This is destructive to the trees and strongly discouraged. Silvopasture systems require careful planning to determine management that is beneficial for all three components: the trees, the forage, and the animals.

Silvopasture can be created by one of two methods. The first method is conversion of a forest into silvopasture. This can be done by removing trees that are not deemed desirable as components of the final system, then seeding forage plants underneath the remaining trees. The seeding process can often be difficult, because of the stumps and debris left over from forest clearing. Broadcasting seeds may be the best means of establishment. Another seeding technique is “feed through,” in which animals receive feed containing ripe seed, such as mature hay, while they are confined to the trimmed forest.

The second method of creating silvopasture is by establishing trees in a pasture. The trees must be protected from browsing by livestock, deer, and rabbits. Protective tree shelters are commercially available and are reasonably effective. Putting trees in rows protected by multistrand electric fences on both sides can be very useful. It may be important to inoculate some tree species (oaks, pines, pecan) with ectomycorrhizal fungi spores, as these spores are often not present in a pasture that has been devoid of these species of trees for many years.

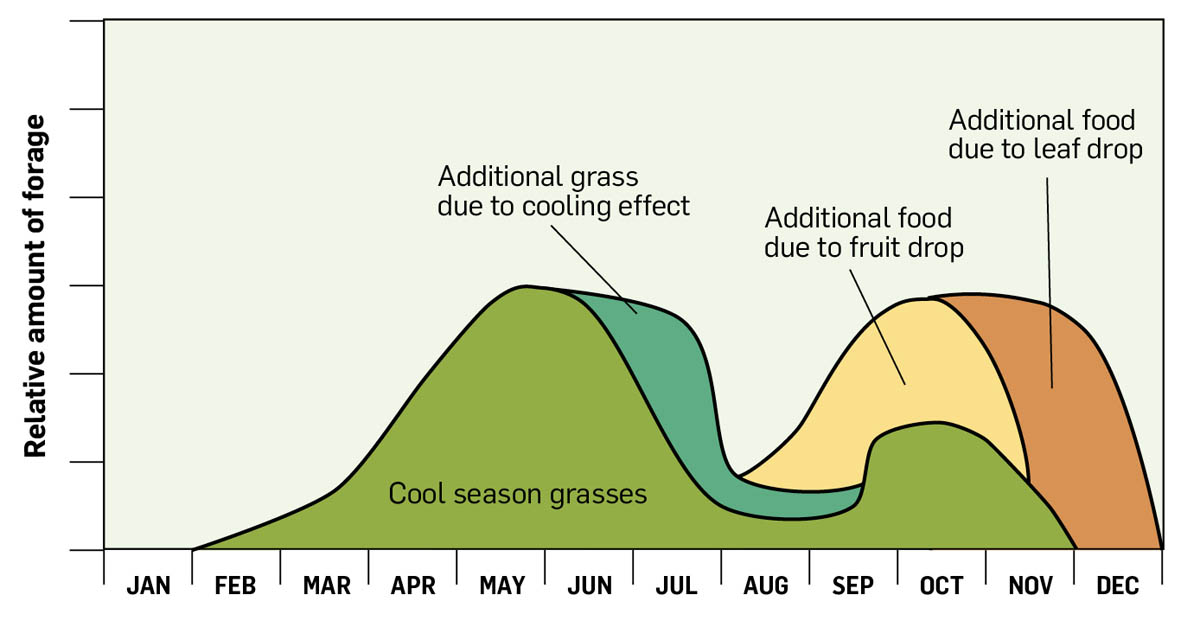

Many cool-season C3 species of grasses and legumes will achieve maximum photosynthesis at light levels well below 100 percent sunlight intensity. Thus, there is often a surplus of sunlight that could be utilized by a light overstory of trees without harming the production of the herbaceous layer below. During the summer, when this surplus sunlight is available, cool-season species typically suffer from excessive heat. The cooling effect of a tree overstory can reduce the temperature at the ground level and increase forage production.

Since the amount of sunlight is so much greater in summer than in the fall and winter, incorporating fruit and nut trees allows the conversion of some of this excess summer sunlight into tree leaves and fruits. These will drop and become available to livestock in the fall when there is typically less forage production due to decreased sunlight and lower temperatures.

Potential products of agroforestry, in addition to the obvious forage, can be timber, fruits and nuts for human consumption or cash, fruits and nuts for livestock consumption, browse for livestock, medicinal products, mushrooms, and additional nitrogen fixation.

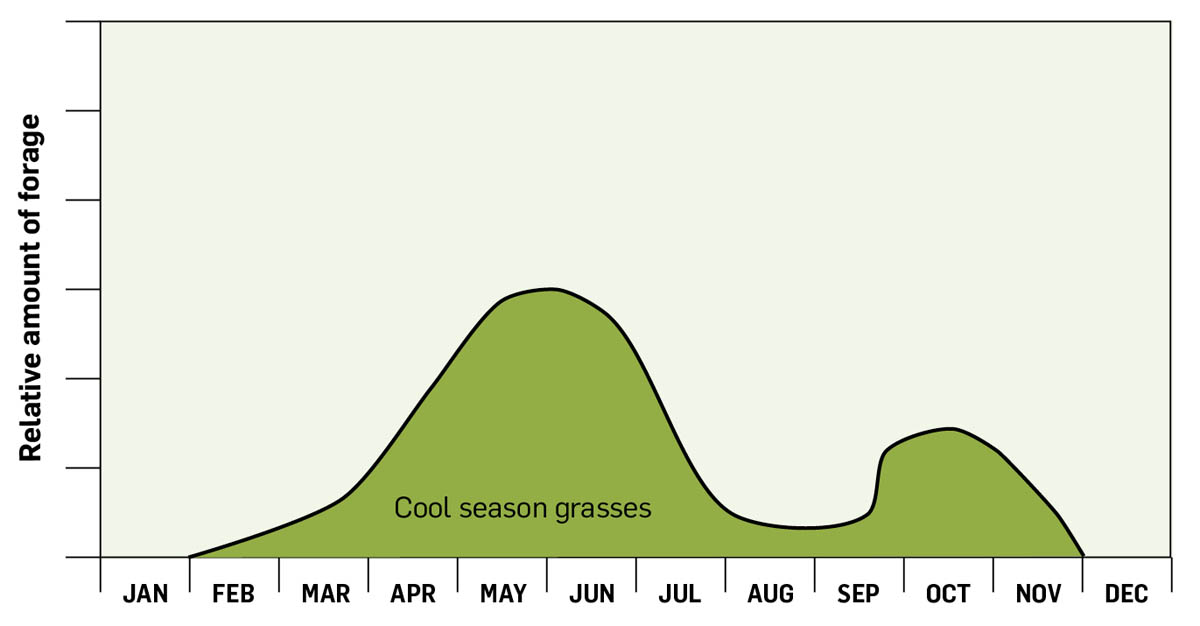

Cool-season grass productivity in open pasture

Productivity of a silvopasture with cool-season grasses and fruit-producing deciduous trees

Black walnut produces an edible nut of unique flavor. The wood has a very high value for furniture, although the price has dropped due to the reduced demand for wood paneling in the past couple of decades. Black walnut shells are very hard and break into cubical pieces upon grinding, which makes them an ideal material for use in sandblasters to remove paint without damaging underlying metal. The trees can be tapped for syrup, like maples, and the syrup has a sweet but subtle nutty taste. Black walnut trees leaf out late in the season, have an open canopy that lets a large amount of sunlight through, and drop leaves early in the fall, all traits that help forage production.

Pecan produces an edible nut of considerable commercial value. Like black walnut, it leafs out late, has an open canopy, and drops leaves early in fall.

Thornless honeylocust produces a high-sugar pod in the fall that livestock relish. These pods are dry when they drop and are usually twisted so that only a small portion is in contact with the earth; thus they can lie on the ground without decaying for much of the winter. Most wild honeylocust trees produce large, toxic thorns that make them an extreme nuisance in pastures, but there are thornless versions.

In the 1920s, there was considerable research into using honeylocust as a source of both winter livestock food and sugar for ethanol production, but the development of the self-propelled grain combine made corn a crop that was much easier to mechanize (thus cheaper) and to produce, at least in the days when iron and fuel were cheap. Thornless honeylocust is a palatable source of browse for all classes of livestock — even horses, which are not known for much browsing.

The canopy of honeylocust is open and lets considerable sunlight through. Since honeylocust pods can provide winter food without any need of human intervention, perhaps we should revisit using honeylocust plantations with an understory of species valuable for winter stockpiled forage such as novel endophyte tall fescue, small burnet, or some of the winter browse species described below. Such a system, to me, seems quite superior to spending all summer swathing, raking, baling, and stacking hay, then spending all winter hauling that hay to the livestock.

Mulberry is also a multipurpose tree. The leaves are a preferred browse species for livestock and are amazingly nutritious. The fruits drop in early summer, when few other fruits are available. These fruits are not used much commercially, since they do not store or transport well, but are a favorite of farm children (including me) when eaten fresh off the tree. These fruits are greedily devoured by pigs and poultry, as well as nearly every species of wildlife.

The versatile mulberry provides leaves for ruminant browsing as well as fruit for swine, poultry, or wildlife.

Persimmon drops a high-energy fruit in fall and will grow in some of the most inhospitable soils you can imagine. I know of a former limestone rock quarry where all the soil was scraped off years ago, and there is now a persimmon forest growing in cracks in the bare rock. Persimmon fruit has a high energy density and is relished by all livestock. Persimmon leaves are not considered useful browse by most livestock species, which may be an advantage in that they do not need protection, at least from cattle.

Oaks produce useful timber and drop abundant crops of acorns that can be utilized by swine. Acorn-fed pork has come into vogue with upscale chefs and commands a premium due to its rarity. Yields of acorns per acre are often quite impressive, and acorns are roughly equivalent to corn in nutritional value, low in protein but high in carbohydrates.

Chestnut is another tree that produces a high-carbohydrate nut, similar in nutritional value to corn. In centuries past, before the chestnut blight wiped out the America chestnut, as much as 50 percent of the eastern forest of North America was chestnut. It was the staple food of not only most of the wildlife of the eastern forest but also of the American Native tribes of that region. Reports are that after humans arrived, the percentage of chestnut pollen in the fossil record went from about 5 percent of the total up to 50 percent of the total, indicating that the natives were actively encouraging the chestnut population. Maybe they figured something out that we have ignored.

The American chestnut may be all but gone, but there are hybrids of American and Chinese chestnuts available, as well as hybrids of European, Japanese, and Chinese origin. Yields from well-managed chestnut orchards can rival corn in production of carbohydrate per acre, even given today’s corn yields. Chestnut-fed pork has a unique flavor and is in demand by upscale restaurants.

Apples and pears are familiar fruits for human use but can also be used as livestock food. My mother-in-law has a couple of apple trees and a couple of pear trees in her yard, and every fall these trees produce far more fruit than we could ever hope to utilize. The excess falls to the ground, and every day for several weeks I gather several bushels of fallen fruits and haul them to my cows, who literally fight over them. One day after a good workout of picking up and carrying these bushel baskets of fruit to the cows, I thought maybe it might make more sense to take the trees to the pasture instead of just the fruit, so I could skip this daily exercise and let the cows pick up the fruit themselves. Apples and pears drop in fall to provide a high-energy supplement when pastures typically become less productive.

Pines are used for rapid-growing lumber and pulpwood. They furnish little available forage for livestock but are quite valuable as windbreaks in winter pastures.

Hazelnuts produce nuts with protein and oil content similar to soybeans, and studies have shown per-acre yields similar to soybeans once hazelnut shrubs are established. The nuts can be harvested for the human market, used to produce oil (which may then be converted into fuel oil or biodiesel), or eaten by pigs as a protein supplement. The shells burn at temperatures similar to coal and can be used for forges or similar to wood pellets in home heating. The go-to resources for hazelnut agroforestry are the Badgersett Research Farm (www.badgersett.com) and the Arbor Day Foundation (www.arborday.org).

Suitable understory plants should be shade tolerant and not compete with the trees.

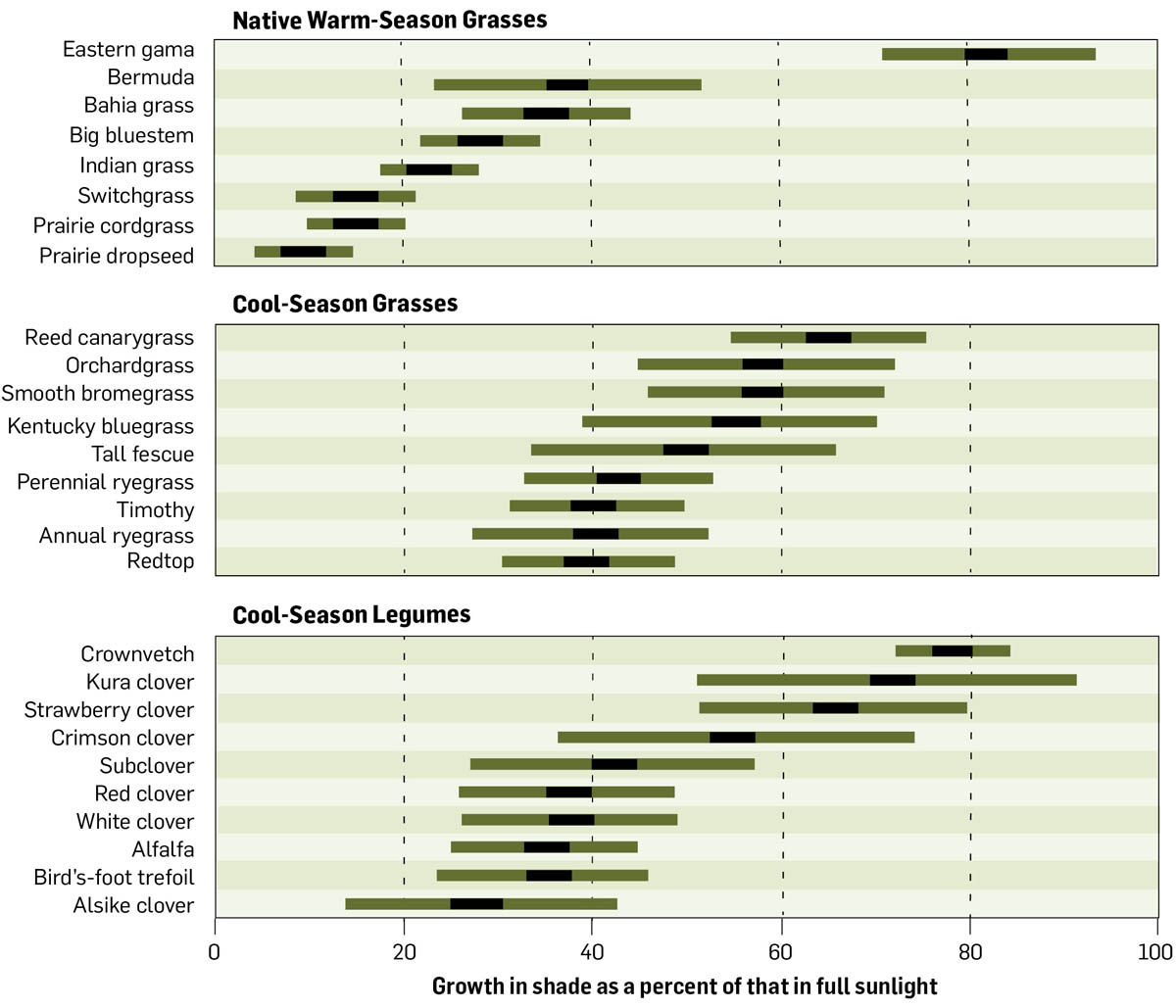

Not all forages tolerate shade equally. As can be seen from the graph, the only warm-season grass with good shade tolerance is Eastern gamagrass. The most shade-tolerant legume with good forage value is kura clover, and the most shade-tolerant cool-season grasses are reed canarygrass, Kentucky bluegrass, and orchardgrass.

Grasses known to inhibit tree development in the early stages include tall fescue and smooth bromegrass. These species should not be planted in close proximity to trees.

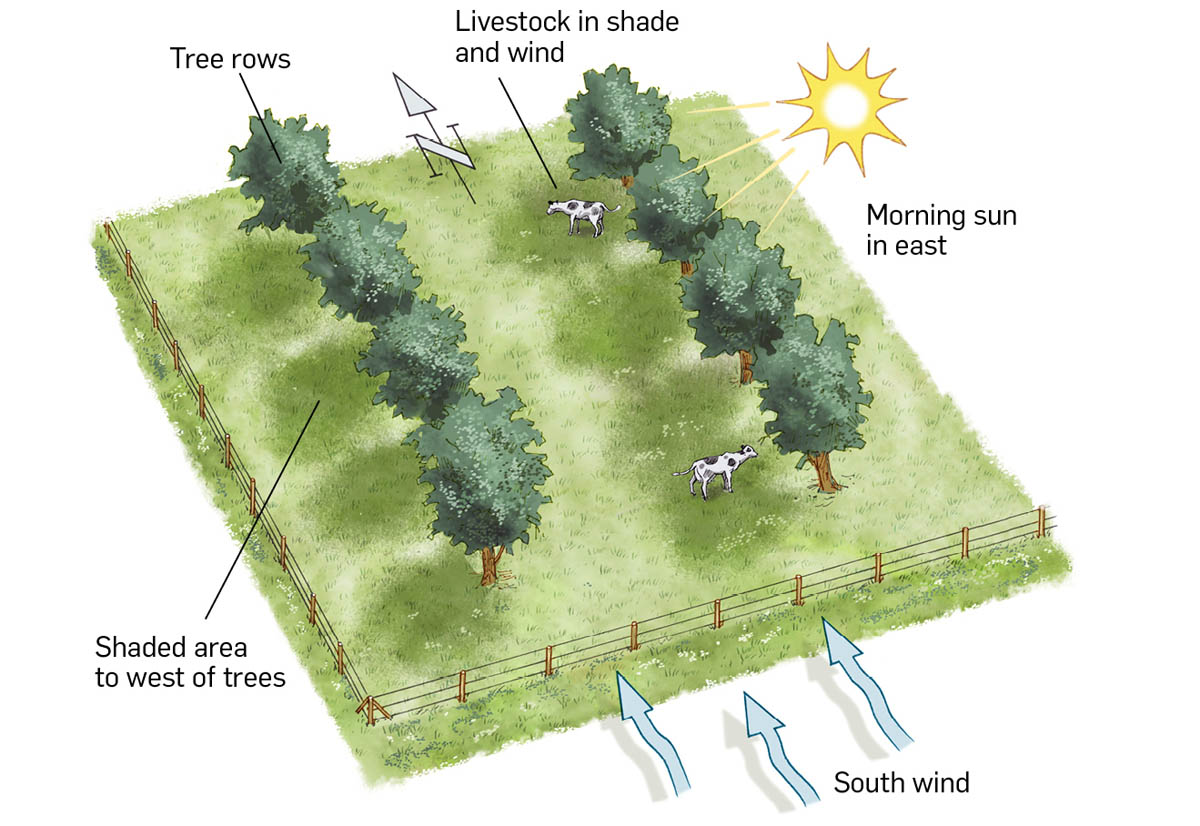

Shade in summer is an obvious benefit of trees in pastures. To make maximum use of trees for a cooler summer environment, tree rows should be placed in a north-south orientation (at least in my region of the United States, where the prevailing summer winds are from the south). This also distributes the shade throughout the pasture as the sun moves across the sky. In the morning, the shade is on the west side of the tree belt. At noon, the shade is directly underneath the trees, and during the late afternoon the shade is on the east side of the tree belt. The summer wind blows between the tree rows so that animals can stand in both shade and wind. Animals with access to simultaneous shade and wind in the heat of summer will spend more hours feeding and perform better.

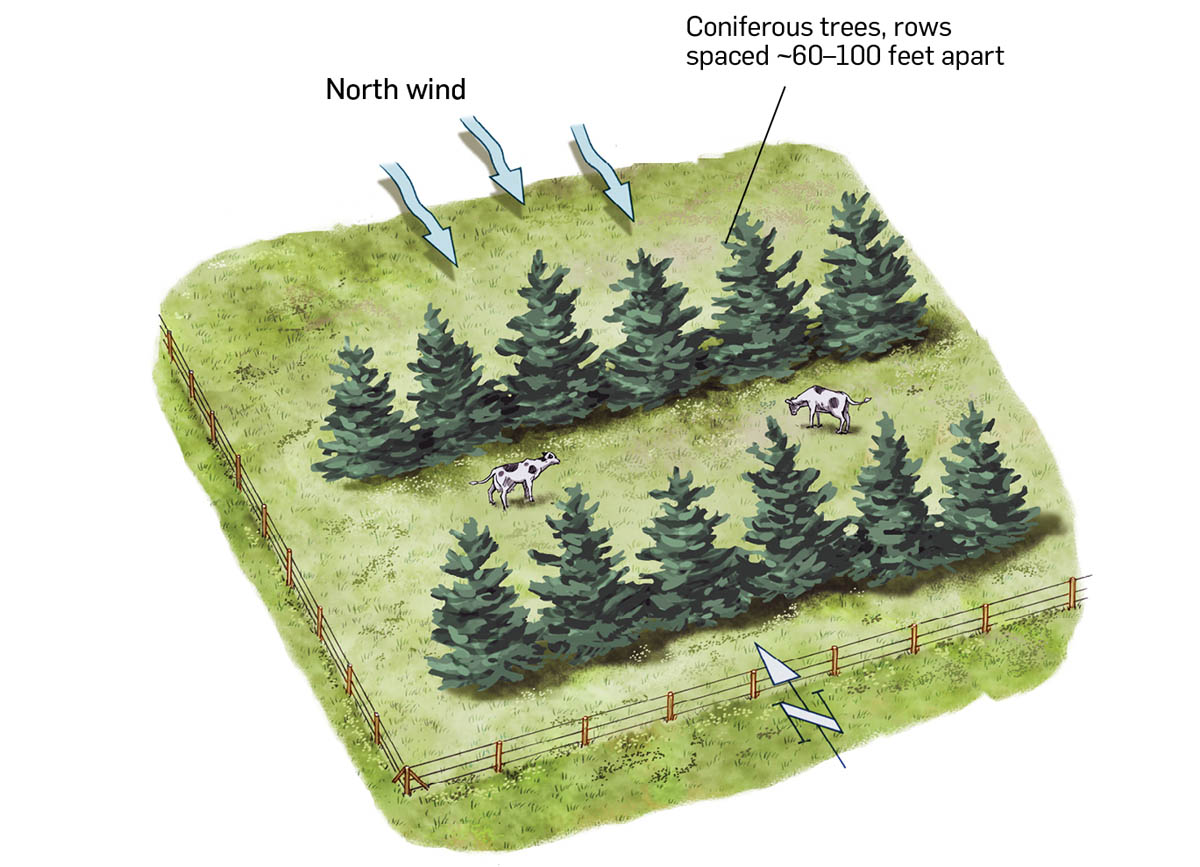

Shelter from wind in winter is another potential benefit, although to provide this the trees should be coniferous evergreens such as pines. In my area, the prevailing wind in winter is from the north, so an east-west orientation will slow the wind velocity. Studies show that as wind velocity decreases in winter, animals require less feed.

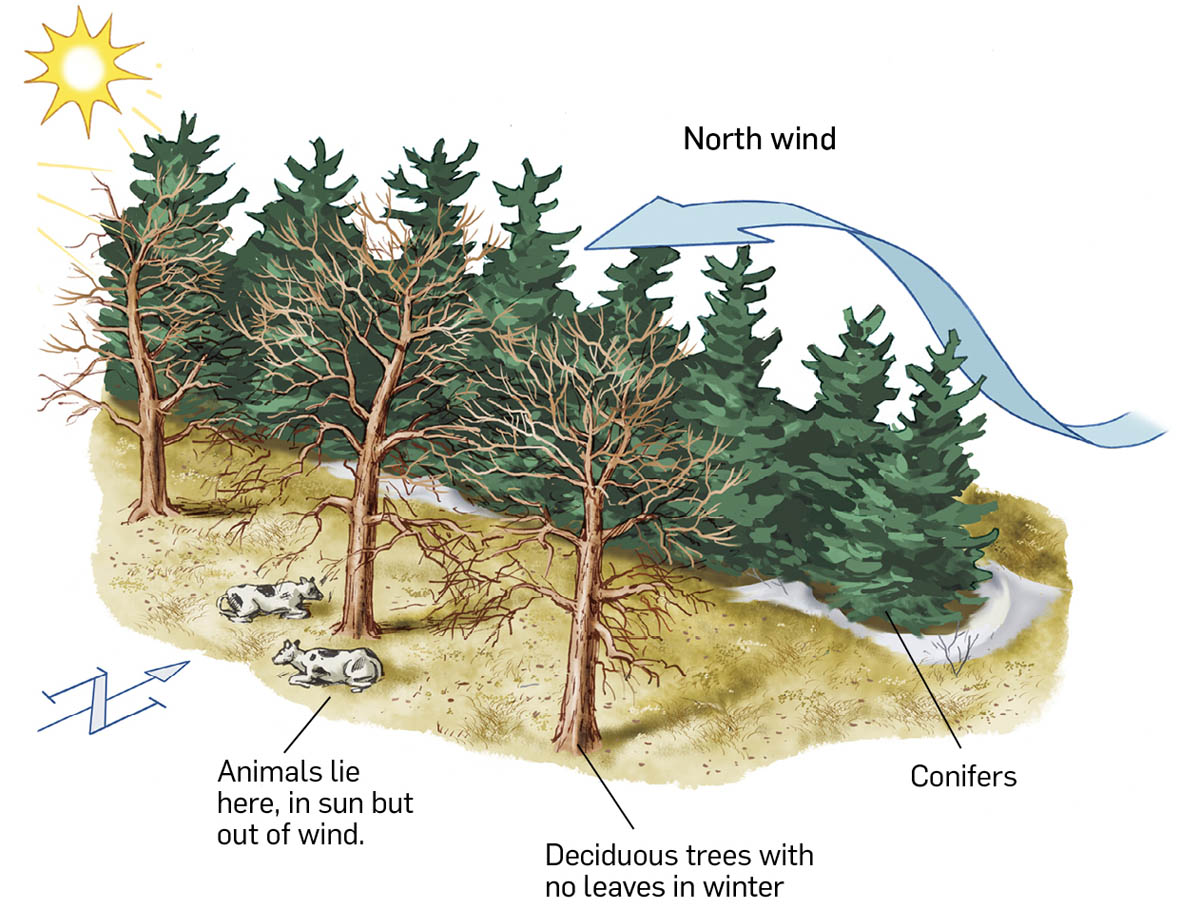

Living barns are clusters of trees in which livestock can seek shelter during severe weather. There are two common designs for living barns. One is a simple block of closely spaced conifers; the other is a U-shaped arrangement of conifers, with the open end facing south, and the middle filled with deciduous trees, which slow the wind flowing over the conifers but allow sunlight through to the animals below.

Living Barn

Shrubby undergrowth is ideal for goat pasture. Browse is the use of the leaves of woody plants for livestock feed. Goats use the leaves of most woody plants as the preferred part of their diet, but producers don’t usually think of feeding woody plants to livestock in this country. Tree leaves can be particularly valuable feed in late summer, as they do not lignify as the season progresses. Lignin, remember, is the structural fiber plants use to hold themselves up. Tree leaves are held up by the twigs and have little need for lignin in their own structure.

Tree leaves are also typically high in both protein and minerals. In the fall, leaf drop can add a significant amount of biomass to pastures where deciduous trees are abundant. Fallen tree leaves after frost are usually much lower in protein and minerals than green tree leaves but are often surprisingly superior to many pasture grasses at that time of year.

Dropping trees can be a source of emergency forage, or part of a regular planned forage system if trees are abundant. One of the best ways to utilize dropped trees for browse is to cut down undesirable trees while livestock are present in the paddock. For example, in my area woodlands are often invaded by elms and hackberries, which have no commercial value but do provide useful browse. I try to thin out these trees while those paddocks are being grazed in late summer, when the trees are fully leafed out and forage is often scarce.

Windbreak

Shrubby undergrowth is ideal for goat browse.

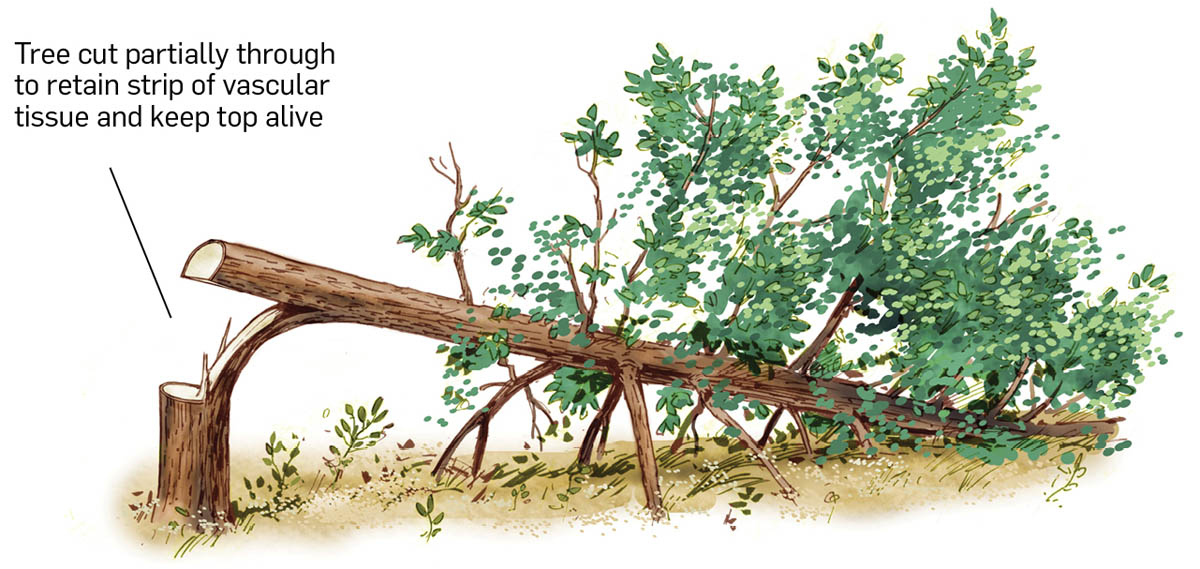

Hinge cutting trees, which leaves the tree top partially attached to the bottom, will keep the tree top alive to generate a new crop of leaves that are accessible to livestock.

Hinge cutting

Coppicing is the act of cutting down trees close to ground level so that the regrowth is accessible to livestock. Most deciduous trees coppice well.

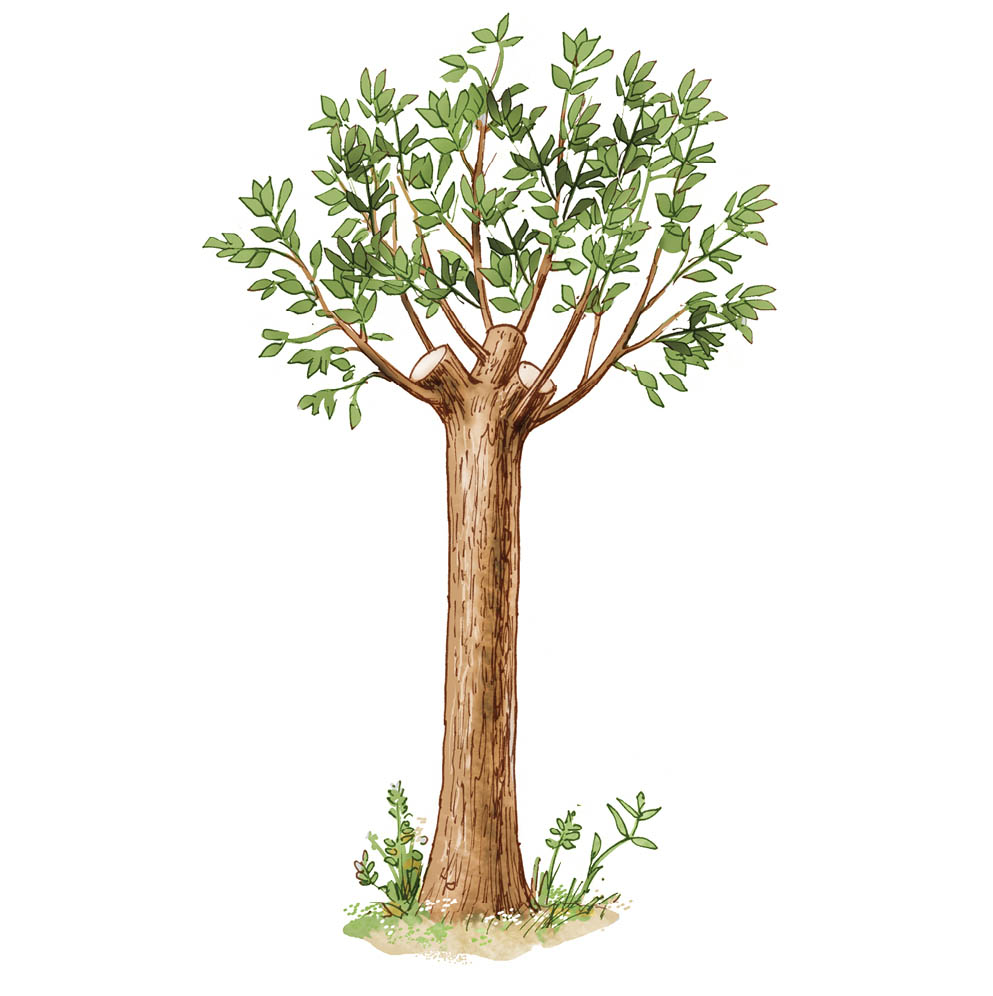

Pollarding is similar to coppicing, except the trees are cut farther above the ground, usually above the reach of livestock. This usually increases the amount of regrowth.

Pollarding

Cut and carry is when trees are felled in one area and brought to another for livestock supplement. In many areas of the world, this is a common practice. In this country, it is too labor intensive to be a regular part of a forage program, but if trees are to be removed for any reason from any area, disposing of them in a pasture inhabited by livestock can provide welcome forage. In an emergency, it should also be a consideration.

Browse plants add to summer forage in temperate areas.

Willows and poplars, including cottonwood, are palatable and have the recently discovered additional bonus of nitrogen fixation through bacteria found in the stems. This explains these trees’ ability to grow in waterlogged conditions, where soil nitrogen is subject to loss by denitrification. They are usually found in wet areas and are most often selected by livestock in late summer when wet areas dry up.

Alders are also nitrogen fixers but do so through a symbiotic relationship with the fungus actinomycete Frankia on their roots, rather than with bacteria. Their forage, like that of other nitrogen fixers, is high in protein.

Alder

Mulberries furnish both high-sugar fruit and leaves that are as high in protein as alfalfa hay, and as high in digestible energy as corn silage.

Mulberry

Mimosa is utilized as forage where it grows abundantly. It is a legume and fixes nitrogen.

Mimosa

Black locust is utilized extensively as a browse plant in eastern Europe but is seldom used for that purpose in the United States, where it is native. It is a legume and fixes considerable nitrogen. It reportedly contains some toxic compounds so should not form the major portion of livestock diet for any length of time. It is a valuable species for rot-resistant fence posts and firewood.

Elms are relished by livestock, particularly the larger-leafed American native species. I have found that the small-leafed Siberian elm is much less preferred.

This list is far from complete; these are just ones that I have personally used. I am sure there are many other tree species that livestock find palatable and nutritious.

In the tropics, there are hundreds of species of trees used for livestock fodder, including many acacias, mesquites, Gliricida, Albizia, leucaena, tagasaste, and others. Many of these trees are leguminous and fix nitrogen. My familiarity with their use extends as far as a few visits to ranches where leucaena was used for livestock forage and deer attractant. Therefore, I will only go so far as to point out that in more tropical areas, using trees for livestock feed is a well-developed and accepted practice. Perhaps we could learn a thing or two from those folks.

Cottonwood

Several shrubs serve as browse plants for winter forage.

Fourwing saltbush is a desert shrub, native to the western United States. It grows as high as 6 feet and retains its high-protein leaves all winter long. It is planted in rangeland revegetation, and reserved for winter use in areas where it occurs naturally in large tracts, such as salt flats. As the name implies, it is quite tolerant of salt and should probably be used more for reclaiming salt-impaired areas. It is a member of the Chenopod family, which means it has the water-efficient C4 method of photosynthesis, explaining its drought tolerance.

Forage kochia (Bassia prostrata) is a semishrub that is imported from the area in Asia just south of Russia. It would likely be planted over millions of acres were it not for its unfortunately having been given a name similar to that of the hated weed kochia (Kochia scoparia), which is known as tumbleweed, an annual that breaks off and is rolled by the wind, spreading seed all over the countryside. The weed kochia has also developed resistance to many herbicides and is one of the most difficult weeds to control in the American West.

Forage kochia has none of those negatives. It is a perennial rather than an annual, does not break off and tumble, and has no known resistance to herbicides. It has no reputation for spreading, and it was evaluated for decades for weedy potential by the USDA before its release as a forage crop in this country, with little risk of becoming a weed.

It is also a C4 plant and extremely drought tolerant. It retains its leaves in winter and is high in protein. It competes well against cheatgrass and is often used to defend against wildfire, seeded in strips in a pure stand to serve as a greenbreak (a strip of green vegetation that functions as a firebreak), because it does not carry fire well at any time of year.

Research has shown that, compared with pure stands of grass, mixtures of grass and forage kochia can carry several times the number of animals in winter with much better animal performance. The original variety released in the United States was called ‘Immigrant’, but a new release called ‘Snowstorm’ is taller, protrudes better above snow, and is much more productive.

Winterfat is a semishrub native to the United States. It has a reputation among western ranchers for being a preferred winter forage for all classes of livestock. It is also a C4 plant and very drought tolerant.

I have personally planted both fourwing saltbush and forage kochia in small trial plantings on my ranch in northern Kansas, where they both performed quite well, so I suspect they could both be utilized well outside their native range, perhaps in combination with tall fescue as dedicated winter pastures. The only problem I ran into with them was that my little planting became the home of every rabbit in Kansas as soon as it snowed, and they decimated my planting during its first winter before I ever got to see how cattle would utilize it.