12

Win the War of Words in Writing

Because sometimes writing your argument is the only way, and sometimes it’s the winning way

Reports. Memos. Letters. Putting your thoughts in writing enables your reader to reread, to absorb, and to understand—luxuries listeners don’t have. We write hoping that we’ll be read. But you never really know if you’ll be read, or if the reading will be anything more than a fleeting, light, once-over.

In this chapter you’ll discover the secrets of how to write an argument that will be read.

Meet Mrs. Townsend

Because it’s time for you to be set free

Upright and proper, Anna Townsend referred to herself not as our English teacher, but as a “teacher of English.” God forbid that anyone would mistakenly think she was a teacher from England.

“The King’s English.” That’s what Wilson High School’s Anna Townsend called it. I called it “excruciating”—the tyranny of the pluperfects, those horrible predicates, the intransitives, split infinitives, gerunds, participles, and subjunctives. Be honest: Have you ever met anyone who claims grammar was their best subject? Or their favorite?

Mrs. Townsend’s labyrinth of rules were the rules of formal expression. She had a say-it-my-way-or-no-way attitude about English. A lot of high school reunions later, I realize that Mrs. Townsend’s rules are a framework, not a mandate.

From the time we have our first cup of coffee until we go to bed at night, we are assailed by persuasive writing of every kind and description. You write hoping you’ll be read. Writing that does get read has a style that pulls readers in, not shuts them out. Style that is expressive. Imaginative. Style that allows your personal touch to shine through. It’s all possible because today’s King’s English is the English of Larry King, Don King, Stephen King, Martin Luther King, and B.B. King.

Okay, I’ve set you free. But come-as-you-are found freedom isn’t a license to wear sweats to the wedding. The written word will always be a little more formal than the spoken. But it’s not the end of the world to begin a sentence with but or to end a sentence with a preposition. Or to even have sentences that aren’t really sentences. You know. Those things Anna Townsend called “fragments.” You don’t have to get all worked up over who versus whom and like versus as. You’re not getting graded and you won’t be sent to grammar re-education camp.

Create a Hi-Touch Link-Up

Because convincing writing is convincing conversation in print

Arguments presented intellectually don’t build trust. Trust is a reader’s “good vibes” emotional response to how you are. Writers talk to readers. Let your ear guide your writing. Convincing writing is convincing conversation in print.

It’s the “Does this sound like me?” test: Use words that real people use in real conversation. Advertisers hype their products as being robust, zesty, hearty, tangy. But has any conversation in your house ever sounded anything like this:

Person A: “Honey, what did you think of lunch?”

Person B: “The fruit drink was tangy, the salad dressing really zesty, and the stew was sure hearty, Dear.”

We talk to each other in an active voice. When talking, you wouldn’t say, “It is recommended by our councilwoman that we unite in opposition to the multiplex.” You’d say, “Our councilwoman recommends….”

Before writing, take the time to think about what you’d say if you and your reader were arguing one-on-one. Now, say to yourself out loud what you would say if you were arguing face-to-face.

Quickly write down exactly what you said. You’ll find yourself verbalizing emotions and thoughts that you wouldn’t have otherwise put on paper. Don’t correct your grammar. Don’t move your words around. Just write down what you said, word-for-word.

It’s only when you’ve run out of ideas that it’s time to thumb through your notes. Some of the ideas that sounded good will come across as duds on paper. Toss those ideas out. Not all ideas will make your cut list.

Here’s the hard part: not giving into your temptation to change vocabulary. Sure, formal words may better express your point, but they may also leave your argument sounding stuffy or pretentious. A radio advertiser claims it can give you the “verbal advantage” because a “powerful vocabulary gives a powerful impression.” But winning arguments don’t come from talking down to the other guy. Your goal is to win, not to impress.

Use small, mainstream words when you can. If a long word says just what you want to say, do not fear using it. But know that our tongue is rich in crisp, brisk, swift, short words. Make them the spine and the heart of what you say and write.

Will short words make you sound like a fourth-grade dropout? Decide for yourself. The quoted paragraph that you just read, from Richard Lederer’s The Miracle of Language, is crafted almost entirely of one-syllable words! And here’s a power-up plus: Words with the same meaning become more powerful as the number of syllables decreases 4-3-2-1. Which words in each line do your find most powerful?

Debilitate > undermine > weaken > sap

Accumulate > assemble > gather > stack

Erroneous > fallacious > faulty > wrong

Power up with “fireplug words”—short, punchy, graphic, to-the-point utility words. Which of these brims with power?

Take 1: A bear cub knocked everything off the shelf, tore our sleeping bags, and left the tent a mess.

Take 2: A bear cub trashed our tent.

In Take 2, 18 words were reduced to six by using the commonly understood fireplug word trashed. By dropping 12 words, a soggy sentence became crisp and memorable.

Would you call this award-winning writing? “Please read these materials so that you’ll know what we plan to do at the meeting.” This sentence is from a Ford Motor Company shareholder proxy statement. The statement’s simplicity and the conversational quality of the accompanying letter from Ford’s chairman won the automaker the Michigan Bar’s annual Clarity Award.

Oh, if you’re still worried that you’ll sound like a dropout, try saying, “I’m just not the sesquipedalian I once was” (a long word meaning someone who is into long words).

How to Grab a Reader’s Attention

Because you want to create an undertow

Whether your argument is part of a report or memo, or a stand-alone letter, you want your argument to grab interest and create an undertow that will sweep the reader down the page.

To get their attention, you have to hit people with a two-by-four. Subtle just doesn’t work anymore, advises the editor of a persuasive writing newsletter.

Opening words should pop with energy: “You may think you’re Jesus, but I know you’re not because you wear glasses” (from a client’s letter to her congressman who had a “preachy” attitude).

Will your writing be one of many that will be received? “One way to pull away from the crowd is to use sarcasm,” advises California Lawyer magazine. “If a paragraph is an unusual experience, it will carry its point.”1 “Does pink make you puke?” That’s the leading question in an advertisement for Urban Decay, whose nail polishes are a far cry from traditional pinks and reds.

How do you convince the 79 percent of men and 42 percent of women who presently don’t wash their hands properly after using the bathroom to start practicing basic hygiene? (Their mothers’ nagging didn’t seem to work, so that’s out as an option.) You start by grabbing their attention.

In an attempt to do just that, the Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Health Department found a way to grab people’s attention and at the same time educate them to the real potential harm not washing their hands has on themselves and others. How? By tweaking the opening lines of famous literature and posting the results on public restroom stalls. Some off-the-wall samples:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…it was the era of people not washing their hands after using the bathroom, it was the era of people eating with their hands and falling violently ill after transferring bacteria to each other. In short, it was not a very sanitary period.”

“Scarlett O’Hara was not beautiful, but men seldom realized it when caught by her charm….Scarlett had frivolously not washed her hands after attending to her business in the ladies’ parlor…. Her delicate hands, being so unguarded…causing the unfortunate spread of an atrocious bacterial disease….”

Would Allegheny County’s hygiene argument have been as effective if it had simply posted signs saying, “Be healthy. Wash your hands.”?

How to Sculpt and Shape What You’ve Written

Because the less you write, the more people will remember

The Ten Commandments are 173 words long. Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is 266 words long. How many words are in the argument you’ve written? No one needs to tell you that ours is a hurry-up, just-tell-me world. Be direct. Did you over-inform or over-educate? The more filler and fluff you eliminate, the more likely your argument will get through.

Did you write things that are interesting, but not relevant? The executive director of a local charity wanting Bloomingdale’s to put on a fashion show fund-raiser sent this solicitation letter to the Bloomingdale’s CEO:

“Please find enclosed the materials that I promised you in my letter of last week. I apologize for the delay in getting these to you, but the office building out of which we work experienced a small fire on Tuesday. No damage was done to our actual offices, but our computer system was adversely affected for a few days.”

Do you think the CEO really cared about the fire…or the amount of damage to the charity’s offices…or what happened to the charity’s computer system?

And did you write things that are relevant but not interesting? My wife and I will often take a guided tour on our first visit to a foreign city. It’s our way of getting a quick handle on what the city is all about. It doesn’t matter what the country—tour guides the world over launch into excruciating detail about events and people that no one on the tour really cares about. By the time the tour ends, we’ve forgotten most of what we heard—overdosed on detail.

I was putting the finishing touches on this chapter while vacationing “down under.” A tour of the city of Christchurch included a visit to its botanical garden. Our guide’s who-the-heck-cares tidbit: “Enoch Barker was the first Government Gardener of New Zealand.” Ho hum. That was in 1863.

To carve his famous statue of David, it is said Michelangelo took a block of marble and chiseled away anything that didn’t look like David. Here are three clutter cuts to sculpt away anything that doesn’t look like it will advance your argument.

Cut #1: What is the point of all this?

Scrap the folklore and frou-frou. Let your personal style shine through—but too much is too much.

Cut #2: What’s in it for the other guy?

Edit out anything that goes purely to your own self-interest. Sure, you can make your appeal to a man’s better nature, but he may not have one. A bulletproof argument tells the other guy the payoff in it for him.

Cut #3: Are you telling the other person what he already knows?

Telling a listener or a reader what is obvious is a drag. How many times a day do you suffer through this example:

Hello, this is John Jones. I can’t answer my phone right now because I’m either on another line or away from my desk. Please leave your name, the date and time you called, your phone number, any message, and the best time to call you back. I’ll call you back as soon as I can.

Cutting out the obvious reduces this message from 55 to 18 words:

Hello, this is John Jones. I’m not able to take your call. Please leave a message. Thank you.

Even better is Joann Smith’s voice mail: This is Joann Smith. But enough about me. Beep sound prompting caller to leave message.

Okay, every rule has its exceptions. And here are the four exceptions to the “Get on With it Already” Rule:

1. When you’re cranking out an argument as part of a college term paper with a minimum page requirement.

2. When you’re telling a compelling story as part of your persuasive pitch.

3. When too brief is simply too brief:

The Eskimo Cookbook’s recipe (in its entirety) for boiled owl:

1. Take feathers off.

2. Clean owl and put in cooking pot with lots of water.

3. Add salt to taste.

4. When super “overkill” best hammers home your message.

On episodes such as “Your Love Is Mine!” and “Explosive Betrayals!” Jerry Springer Show guests have been known to strip down to their underwear and divulge their most intimate secrets. Do you have even a smidgen of a doubt as to how columnist Mike Downey feels about the show when he argues that it is “…the most repulsive, rotten, slimy, dirty, disgusting, vile, grotesque, stinking, depraved, demented, dreadful, putrid, rancid, appalling, shameless, heartless, mindless, worthless, cruel, crude, creepy, nasty, sleazy, sickening piece of filth in the history of American television.”2

How to Advance in a Linear Progression

Because winning arguments pass the “Moving Forward” Test

Each sentence and paragraph needs to say something different from the one that preceded it. When reasoning is repeated, readers become confused and lose interest.

You’ll have an urge to repeat points believing that if they’re important, they’re deserving of repetition. But repetition signals that there probably isn’t much new up ahead. Whenever you write “in other words” or explain your explanation, you’re really saying “Sorry, but I didn’t do a very good job of getting my point across the first time.”

Mrs. Townsend circled go-nowhere-tangents in red, saying they were “detours.” Bulletproof reasoning moves forward without deviating and digressing. Steer clear of detours by tying each sentence to a prior sentence and each paragraph to a prior paragraph. Examples of tying words: further, besides, first, when, however, conversely, as a result, for example, even so, finally.

Arguments that pass the Moving Forward Test present background information in a cause-and-effect or chronological order. Points in strongest-to-weakest order. They limit each paragraph to just one idea or one point, and limit paragraphs to seven or eight lines at most. Don’t be timid about using a one-sentence paragraph if it helps get your idea across.

How to Make Your Words Flow

Because you need to sweep the reader down the page

Arguments that flow make the easiest reading. Read aloud what you’ve written. Do the words trip easily across your tongue? When they do, you’re on a winning track. Words should have a rhythm and sound good together. Breaks within a sentence should come at a natural point. When your words are read aloud, where will your reader pause for breath?

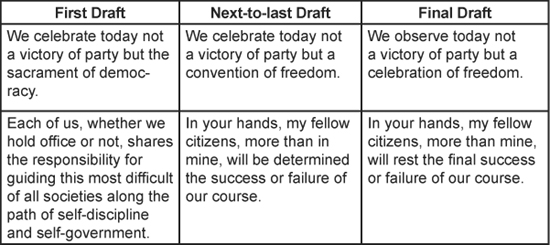

The inaugural ceremony is a defining moment in a president’s career. John Kennedy wanted his address to be short and clear. (The final draft was 14 minutes long.) Though his colleagues submitted ideas and drafts, the final product was distinctly the work of Kennedy himself. Aides recount that every sentence was worked and reworked until it was listener- and reader-friendly. The climax of his speech was its most memorable phrase: “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.” A phrase that became more compelling and less clumsy than an earlier draft that said, “Ask not what your country is going to do for you….”

These drafts of the speech from the archives of the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library show how he crafted his trip-easy address:

From the Pros, 4 Tips for Passing the “Trip-Easy” Test

![]() Check for words that end in -sion, -ance, -ment, -ing, -ence, or -tion. Convert those words to trip-easy verbs by dropping the suffix and tweaking the text for fit. For example, “The Company’s argument is” becomes “The Company argues that”; “The planners are in violation of” becomes “The planners violate the.”

Check for words that end in -sion, -ance, -ment, -ing, -ence, or -tion. Convert those words to trip-easy verbs by dropping the suffix and tweaking the text for fit. For example, “The Company’s argument is” becomes “The Company argues that”; “The planners are in violation of” becomes “The planners violate the.”

![]() Check for the word of and replace with the trip-easy possessive form: “The decision of the council” becomes “The council’s decisions.”

Check for the word of and replace with the trip-easy possessive form: “The decision of the council” becomes “The council’s decisions.”

![]() Check for rambling phrases and replace them with a trip-easy word. For example, “at the time that” becomes “when”; “at this time” becomes “now”; “at that time” becomes “then”; “subsequent to” becomes “after”; “prior to” becomes “before.”

Check for rambling phrases and replace them with a trip-easy word. For example, “at the time that” becomes “when”; “at this time” becomes “now”; “at that time” becomes “then”; “subsequent to” becomes “after”; “prior to” becomes “before.”

![]() Check for word combinations that have a pleasing sound. Bloomingdale’s is famous for placing customers’ purchases in a beige paper container on which is boldly printed the words “Brown Bag,” a much more pleasant sound than if the container was labeled “Brown Sack.”

Check for word combinations that have a pleasing sound. Bloomingdale’s is famous for placing customers’ purchases in a beige paper container on which is boldly printed the words “Brown Bag,” a much more pleasant sound than if the container was labeled “Brown Sack.”

How to Make Your Argument Look Like an Easy Read

Because what appears to be reader-friendly gets read

Take a breather.

Enjoy a cup of coffee.

It’s only when you come back that you’ll be truly ready for the “Total Look” Test’s critical questions.

Look—don’t read—at what you have on paper. Replacing periods with semicolons leaves the reader wondering where to pause and reflect. Does your argument look like easy reading? Or something that has to be painstakingly plowed through? Brevity and simplicity (shorter sentences and paragraphs) put your argument within the reader’s easy grasp.

How much of your writing is about you? There’s a difference between showing what you’re all about and egocentric showboating. Chances are better than 50/50 that what you’ve written is too self-centric. Whatever it is you have to say about your company or yourself is a drag. Later on, you can validate who you are in ways that don’t delay or obscure your argument. Check for “I” sentences that are often self-centric: “I feel that a multiplex.” “I think that a multiplex.” “I believe that a multiplex.”

Are your points obvious so that you understand what they mean? Will the reader understand what they mean? Will both you and your reader have the same understanding of what they mean? Reality check: Points don’t become obvious just because you say they’re obvious. Truly obvious points don’t need to be introduced by because-I-say-so words such as absolutely, it appears that, clearly, definitely, in fact, needless to say, obviously, plainly.

Now, double-check for bulletproofing…

![]() Are there a “sounds right” core argument and three supporting points (Chapter 5)?

Are there a “sounds right” core argument and three supporting points (Chapter 5)?

![]() Will it advance your argument to tell a story (Chapter 4)? Do you use an analogy (Chapter 7)? Do you hone in with surgical strike questions (Chapter 8)? Do you trigger and satisfy the reader’s emotional needs (Chapter 9)?

Will it advance your argument to tell a story (Chapter 4)? Do you use an analogy (Chapter 7)? Do you hone in with surgical strike questions (Chapter 8)? Do you trigger and satisfy the reader’s emotional needs (Chapter 9)?

Convincing writing is convincing conversation in print. A winning argument creates trust and throws off “feels right” vibes.

No one will read what you have to say unless you grab and keep their attention.

The three clutter cuts ensure that what you’ve written is interesting, relevant, and on target.

Move your argument forward in a persuasive progression. Repetition causes readers to become confused. “Detours” throw readers off track.

Trip-easy arguments flow and sweep the reader down the page.

When you’re through, look at your argument to make sure it’s brief, that it looks like an easy read, and that it has “sounds right” reasoning.

Name Your Ideas

Because the right name is itself a powerful argument

An advertising agency renamed the tinea pedis malady “athlete’s foot.” Smart move. How likely are you to remember a name like tinea pedis? Could you possibly ever forget “athlete’s foot”?

Cosmopolitan’s cover could have named its featured recipe “5-minute chocolate mousse.” B-O-R-I-N-G. Instead, they called it “5-minute chocolate mousse that will turn your boyfriend into your love slave.”

In the early 1990s, the New Jersey Nets was a pro basketball team nobody wanted to see. The Nets lacked charisma, performed poorly, and had no superstars to attract crowds. The allegiance of local fans was across the Hudson River with the New York Knicks. Jon Spoelstra, the Nets president, had a mega marketing problem.

Spoelstra’s marketing strategy was not to promote Nets games as great basketball, but as great family entertainment. To jump-start his “family entertainment” campaign, he suggested that the team adopt a name that conveys an image of family entertainment: the New Jersey Swamp Dragons. (The Nets arena is located in the New Jersey Meadowlands, a wetlands area.) The owners rejected Spoelstra’s suggestion. That’s too bad because the name sounds like a winner, wrote one sports reporter.

Before a shot was fired in the war against Iraq, the Bush administration named the effort Operation Iraqi Freedom. A name that argued to the world that the war had a just cause: helping the Iraqi people. The 1991 Gulf War was named Operation Desert Shield. The name was a “just cause” argument that we were at war to protect the people of Saudi Arabia. Just cause imagery was reflected in the name given to the 2001–2002 war in Afghanistan, Operation Enduring Freedom, and to the 1992–1993 war in Somalia, Operation Restore Hope. The 1989–1990 war in Panama had a name that skipped the imagery and cut right to the chase: Operation Just Cause.

Back in the Neighborhood

In the anti-multiplex scenario, your argument becomes more forceful when given a name. Two examples: X-out the multipleX and Be a “No Show.”

Craft Tag Lines

Because bite-sized themes are power-uppers

When I say, “You deserve a break today,” you think__________.

Car manufacturers know the value of a tag line:

Engineered like no other car in the world.—Mercedes-Benz

The passionate pursuit of perfection.—Lexus

The ultimate driving machine.—BMW

Better engineered. Better made!—Chrysler

And the bicycle people know the value of a tag line: Schwinn realized that it urgently needed to pop a wheelie to put fun back in the bicycle business. The un-Schwinn-like campaign tag: Cars Suck.

There isn’t a lot you can say about bottled water. Cascade Clear Mountain Spring Water takes on its big-brand competitors with a wink and let’s-not-be-so-serious tag lines: “Water that’s not watered down” and “Water just like Grandma used to make.”

Back in the Neighborhood

Tag lines are attention-grabbing, bite-sized themes. In the anti-multiplex scenario, your argument becomes more potent by crafting a tag line: Multiplex is another way of saying multi-problems.

How do you know whether the tag line you are considering is a winner? It has to pass the T-shirt test. If it would look and sound good on a T-shirt, then you’ve got yourself a pretty good tag line.

Orange County, California, wanted the world to know that it was crawling into the black, having emerged from a high-profile bankruptcy. Its pros’ advice: a memorable tag line to speed those efforts. After weeks of deliberations, the tag line chosen was “Orange County, The Perfect California.” A bad tag line is worse than no tag line at all. Suggestions rejected by the tourism council: “Orange County: So a-peeling” and “Orange you glad you came?”

I know you filled in the tag line blank “McDonalds.” McDonald’s introduced the tag line in 1971 and used it for four years. It was put back into service in 1981 and 1982. Seems like only yesterday? That’s what tag lines are all about. Making points that stick.

Paint Mind Pictures

Because a mind picture is worth a thousand words

Impresarios of influence are artists who paint word pictures to ensure that their argument has clarity and interest.

From a committee chairman’s written report: “The suggested proposal, although appearing to have merit, does not present the most viable course of conduct.” Legendary journalist H.L. Mencken said it better by painting a word picture: “Just because a rose smells better than cabbage doesn’t mean it makes better soup.”

And from that same committee chairman’s report: “It is important for us to ascertain our customer’s true needs and interests rather than accept their remarks at face value.” Songwriter Roger Miller said it better by painting this mind picture: “Some people feel the rain. Others just get wet.”

Back in the Neighborhood

In the anti-multiplex scenario, a mind picture can slam home a point. Just because a guy is fun doesn’t mean you want him to move into your home. Multiplexes are fun, but that doesn’t mean you want one to move into your neighborhood, down the street.

Concrete words create mind pictures. Abstract words don’t.

I was in the market for new corduroy pants, so I telephoned a local store and spoke to Richard, a salesman.

Bob: Do you have tan cord pants in stock?

Richard: Yes, we just got in a shipment.

Bob: Are they darker or lighter tan? Are they a yellowish tan? Or a reddish-tawny tan?

Richard: More of a brownish-grayish sort of tan. I hate to say this, but I’d call the color “squirrel.”

Squirrel was the operative sensory word. My mind was able to picture the brownish-grayish color of our local squirrels and the tan Richard was talking about. And in the what’s-happening-out-there department: Macy’s features Charter Club terry bath towels and rugs in a color you can visualize because it calls the color “reindeer.”

We all remember Katharine Lee Bates 19th-century imagery: “purple mountains majesties” and “amber waves of grain.” But if you don’t remember the following words from “America the Beautiful,” it’s because imagery to be effective must be easily understood and easily recalled by others:

O beautiful for patriot dream

That sees beyond the years

Thine alabaster cities gleam,

Undimm’d by human tears!

Do What Noah Did: Bring ’em in Two by Two

Because more than two is too much

“The man is tall and thin.” What is the immediate picture you got from this sentence? “The man is short, is bald, wears glasses, and is thin.” Did you also get an immediate picture from this sentence? Or did you have to stop for a moment and put the four adjectives together in their proper places?

Plop-Plop, Fizz-Fizz

Because “naturals” add pizzazz to your message

Even as we read silently, we auralize—we hear the sounds of words in our mind’s ear. Persuasive speakers and writers add excitement by picking words with sounds that fit their message.

Some words have natural sounds: beep, hush, splash, gobble, clang, yawn, clink, screech, guzzle, squeal. The musical Ragtime advertises “cascading melodies.” (Can you almost feel the flow and fall of music?) “It’s been years since it was on TV, but no one who saw them will ever forget Alka-Seltzer’s “plop-plop, fizz-fizz, oh what a relief it is” commercials.

Take #1: I heard the bell.

Take #2: I heard the bell clang.

Take 1 is lifeless and dull. But what’s your take on Take 2?

Use Rhyming Words

Because reason with rhyme is more believable

It’s old news. Advertisers use rhyme as a memory aid (“Tough Actin’ Tenactin”). What’s new is that studies reveal rhyme makes ordinary statements more believable. Consistently, a test group found a statement such as “Woes unite foes” more believable than the statement “Woes unite enemies.”

“A profusion of confusion” is what Mr. Blackwell, the famous fashion critic, called the outfit Celine Dion wore to an Oscars ceremony. He could have called it an “abundance of confusion,” but that would not have zoomed his message to readers.

“If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit” was O.J. Simpson lawyer Johnnie Cochran’s rhyming tag line as his soon-to-be-freed client barely squeezed into an incriminating pair of gloves. Do you recall any part of the trial as readily as Cochran’s rhyming refrain?

Sizzle and seasoning make your argument more readable, memorable, and convincing.

Name your idea because the right name is itself an argument. Tag lines are bite-sized themes that are your argument’s linchpins.

Mind pictures create compelling clarity. Rhyme creates believability.

10 Mix ‘n’ Match Tricks of the Trade

Because power comes from positioning

Look at magazine and billboard advertising, and notice how marketing masters compel and convince through the placement or repetition of key words, not the repetition of points! When writing, you have the ability to move words and pieces of words around for a mix that powers up your argument with crescendos of emotion, focus, and emphasis.

Trick #1: Repeat words at the beginning.

This is the technique to use when the beginning words or phrases are less important than the ones that follow.

“Who was Dodi Fayed?” was the topic on the Geraldo Rivera Show. One of Geraldo’s guests suggested that my client, Dodi, may have encouraged the attention of paparazzi on the night he and Princess Diana were killed. A professional spokesperson for the Fayed family persuasively argued otherwise by noting Dodi’s very “protective” feelings toward Diana. Here’s how he used this technique to power up his impromptu rebuttal: “They were dogged. They were pursued. They were harassed…. He wanted to give her security. He wanted to give her peace. He wanted to give her space.”

Trick #2: At the end.

This is when you want to emphasize the repeated word or phrase.

It was the first game of an American League baseball championship series. A 12-year-old boy stuck out his glove and grabbed a ball that resulted in a game-tying home run for the Yankees. “We were robbed,” declared Baltimore’s mayor.

“Baseball is a game of breaks. Good calls, bad calls, in-between calls,” was New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s responsive argument.

Trick #3: Or in between.

“SOME WHO QUESTION THE REASON FOR THIS CONFERENCE…LET THEM LISTEN TO THE VOICES OF WOMEN IN THEIR HOMES, NEIGHBORHOODS, AND WORKPLACES. SOME WHO WONDER WHETHER THE LIVES OF WOMEN AND GIRLS MATTER…LET THEM LOOK AT THE WOMEN GATHERED HERE.”

—HILLARY CLINTON

Trick #4: Repeat words from the end of one clause at the beginning of the next.

“TO BE PERSUASIVE WE MUST BE BELIEVABLE; TO BE BELIEVABLE WE MUST BE CREDIBLE; TO BE CREDIBLE WE MUST BE TRUTHFUL.”

—EDWARD R. MURROW

Trick #5: Repeat prefixes of different words.

“Delegating unclear tasks to an uninspired, unqualified, unorganized committee will be the undoing of our program.”

Trick #6: Or repeat the suffix of different words.

“Her idea was scrutinized, analyzed, minimalized, and trivialized, but in the end, it alone made the most sense.”

Trick #7: Repeating sounds drive home a point.

Lexus boasts being “passionate in the pursuit of perfection.”

Trick #8: Phrases using opposite words are memorable.

“THE COST OF LIVING IS GOING UP AND THE CHANCE OF LIVING IS GOING DOWN.”

—FLIP WILSON

Trick #9: A powerful pulsating effect is created by repeating one word over and over.

“NO KITES. NO BALL-PLAYING. NO RUNNING. NO FOOD. NO BEVERAGES. NO THIS. NO THAT.”

—SIGN ON THE NEW JERSEY SHORE

Trick #10: Omitting conjunctions gives a staccato effect to your words.

Look what happens when you omit the word and:

![]() It was a night to remember. We talked. We danced. We laughed. We cried.

It was a night to remember. We talked. We danced. We laughed. We cried.

But the repeated use of the conjunction and can also be effective:

![]() It was a night to remember. We talked. And we danced. And we laughed. And we cried.

It was a night to remember. We talked. And we danced. And we laughed. And we cried.

Think back. Which of the 10 tricks do you remember best? Would you have been as readily influenced if the tools of rhyme and repetition had not been called into play?

A bulletproof argument is always in the “basics”—what “feels right” and “sounds right” to the other person.

You can add emotion, feeling, drama, immediacy, or urgency to your argument by tactically repeating and positioning key words and phrases. But overdoing it will be an oversell turnoff.

Don’t Get Sucked Into the E-mail Trap

Because what’s efficient may not be effective

Star Trek’s Mr. Spock transfers information between himself and other Vulcans by touching skulls—mind-meld transfers that are direct and free of emotional content.

So, too, our own Information Age transfers are often direct and free of emotional content. As you become more technologically connected, the less connected you are as a life force—an animate being. Mailboxes are made of pixels instead of aluminum, and texting symbols replace words. High-tech connections lack a hi-touch. In the process, are you abandoning the art of the one-on-one, the people skills that make your arguments compelling?

Always ask yourself: What’s my link-up priority?

Here’s how the persuasion pros see it….

![]() High-tech connecting is about getting to. About convenience. Speed. Brevity.

High-tech connecting is about getting to. About convenience. Speed. Brevity.

![]() Hi-touch connecting is about getting through. About movement. Change.

Hi-touch connecting is about getting through. About movement. Change.

![]() High-tech is inanimate. The cutting edge of soulless connectivity.

High-tech is inanimate. The cutting edge of soulless connectivity.

![]() Hi-touch is organic. It’s mystery, magic, and power springing forth from who you are.

Hi-touch is organic. It’s mystery, magic, and power springing forth from who you are.

![]() High-tech is about cyber smarts. About being efficient.

High-tech is about cyber smarts. About being efficient.

![]() Hi-touch is about people smarts. About being effective.

Hi-touch is about people smarts. About being effective.

![]() High-tech best deals with “the stuff in the middle.” The task-oriented, and the fact-based. The when, where, and how’s of your day.

High-tech best deals with “the stuff in the middle.” The task-oriented, and the fact-based. The when, where, and how’s of your day.

![]() Hi-touch builds trust, resolves conflict, influences outcomes, and helps things go your way.

Hi-touch builds trust, resolves conflict, influences outcomes, and helps things go your way.

How will you deliver your message? Will you send an e-mail? Fax from an airplane? Drop a letter in the mail? Call for a meeting? Telephone one evening after the tumult of your day has passed?

Each communication medium comes with its own built-in, implicit message.

Want your proposal to deliver the implicit message that “This is it. Take it or leave it”? Then writing may best serve your purpose. Fax and e-mail traffic arrives with the implicit message that its text has special importance and immediacy. Regular “snail mail” conveys the more laid-back message that “There is no rush.”

If feedback is more important than the implicit finality of writing, then an interactive medium—a meeting or a phone call—will be your choice. Initiating a live conversation conveys a let’s-talk-about-it message. Investing effort in arranging and holding a meeting sends a stronger message that there is a desire to talk things out. If the other guy is skeptical or hostile, you will need a mode that will accommodate more detail and a greater depth of exploration.

According to a former Microsoft employee, James Fallows, in Atlantic Monthly, “Microsoft relies as heavily on face-to-face contact as any organization I’ve ever seen.” It’s easy to pretend you care. Or that you’re concerned. But you can’t pretend to be there. Sometimes the necessary alternative to the Internet is the 747.

New technologies can be persuasion facilitators or persuasion obstacles. What are your communication skills? The other side’s communication skills? People who are competitive are most effective face-to-face. Cooperative people become bolder using e-mail.

Think about your own experiences with conflict. Maybe it was conflict with your spouse, a boss, an employee, a teacher, a student, a neighbor. If that conflict was ever settled, it was probably because, albeit reluctantly, you met face-to-face to talk out your differences.

As you become more technologically connected, you become less “life-force” connected. In our fast-forward world, we too quickly opt for what’s convenient. Winning arguments isn’t about what’s convenient or efficient. It’s about what’s effective.

Chapter Summary

It takes time and effort to write a winning argument. But writing may be your only way. Or your best way because of geographic distance, impossible personalities, or complex issues. But with a writing, you’re never really sure you’ll be read. Whether the reading will be anything more than a fast glance. Or whether you’ll even be understood. A writing doesn’t provide in-person feedback. On the other hand, a written argument gives the other guy the time and space to reread, absorb, and understand. So, what should you do? For each instance, strategize your alternatives.