Establish Regional Entities That See the Big Picture

After two significant grid blackouts in the western interconnection in the summer of 1996, NERC embarked on a program to initiate a newly defined entity with a view of the grid that is at a higher level than the view the transmission owners have. The effort to develop the role, authority, and description of this entity was assigned to an industry task team consisting of primarily operations personnel from across the United States and Canada (I worked with this task team). It also included a few representatives from the marketing community.

After Congress issued the 1992 milestone act stating that the transmission grid must be operated as a common carrier, and once the subsequent FERC Orders 888 and 889 were issued (in 1996), all hell broke loose in operations. I am not saying that the FERC orders were a bad idea; in fact, in the long run they have improved reliability. But the impact in the early days was disastrous. In hindsight, if the industry could have spent a couple of years developing the tools needed to operate under this new model, a lot of problems could have been prevented. As I recall, though, FERC didn’t want to hear about any companies needing more time—and frankly, if FERC had allowed more time for development, grid operators probably wouldn’t have been able to get everyone on the same page without actually experiencing the problems that we eventually encountered.

The issue, in a nutshell, is this: Prior to the new rules, wholesale transactions were done by the system control operators in a simplified method, and it was fairly easy to keep track of them. Once the market opened up and a whole new player was in the loop (the marketer), there were far too many transactions to keep straight. At the same time, we were using the simplistic accounting methods we had always used. It became apparent early on, and especially after the western blackouts in the summer of 1996, that the operators were overwhelmed with transactions.

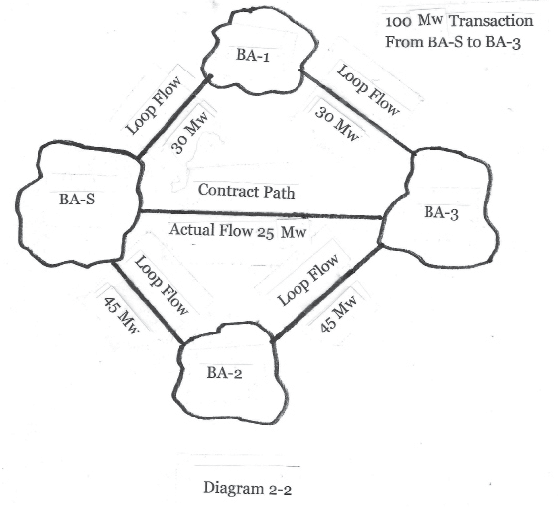

Add to this dilemma the fact that a transaction could be legally arranged that had large current flows through a part of the grid whose operators had no knowledge of the transaction. Why does this happen? It is the difference between the laws of physics and the laws of contracts. The problem is that those pesky electrons don’t care to follow the contract path. Instead, electricity follows the path of least resistance. Without getting into physics, I’ll say that the path of least resistance in a network involves many parallel paths. That is, all the electrons don’t flow on one path through the network (the contract path), but instead they divide up and take numerous paths.

See diagram 2-2, below, for how this might work. I have included this diagram to help illustrate this very important concept of networked systems (like our grid). In this example, a generator in BA-S (the source BA) has purchased contractual rights to transmission through the transmission owners in BA-S to get to the border of BA-S, and has a purchaser within BA-3 who has transmission rights to import power. (The contract path is actually through transmission owners, but I’ve simplified the example to show the BAs, which in most cases would be the same entity as the transmission owner.) In this example, the transaction is for 100 Mw for a period of time. We know that 100 Mw leaves BA-S and that 100 Mw arrives at BA-3, but the flows in a real-life case are even more complicated than the example I’ve provided in diagram 2-2.