We gardeners of today owe a great debt of gratitude to Mother Nature for coming up with such a wonderful edible whose seeds are so simple to save, and most often in an uncrossed state. Of course, our current bounteous selection would not exist if it weren’t for those who came before us with the foresight to save seeds of so many wonderful varieties, as well as the seed-saving organizations and seed companies that work alongside gardeners, providing archives for the varieties and opportunities to share and purchase them.

We all have the choice to preserve our bounty — both by putting up tomatoes for the colder months to come and by saving seeds of special varieties for future gardening seasons. Neither process is difficult, and both are rewarding in countless ways.

Despite all of our best efforts, a successful tomato garden will produce more delights than can be eaten or given away before going bad. Fortunately, the flavor of summer can be preserved for the coming chilly days when one can only dream of the garden. A gardener who is armed with a brief list of preservation methods will be handsomely rewarded with quantities of frozen tomatoes for soups and stews, chewy and intensely flavored dehydrated tomatoes for pizzas and omelets, and multihued quart jars of delicious juice and rich, thick sauce.

Let’s start with the easiest way to deal with an abundance of delicious tomatoes. The entire procedure is as follows: Check fresh-picked tomatoes of various shapes, sizes, or colors to ensure that they have no bad spots or spoilage. Wash and dry them, put them in freezer bags, zip to seal, and place them in a single layer in the freezer. That’s all there is to it.

Frozen tomatoes lose the firm texture of garden-ripe fruit but retain all of the wonderful flavor. The best use for them is in cooked preparations, such as soups, stews, and sauces. The skin will easily slip off if you run the frozen specimens under water for a brief period. After you remove the skin, it’s easy to remove the core (tomatoes don’t freeze solid like ice), after which you can quarter them and add them to your favorite recipe. The only drawback is that you’ll need ample freezer space, especially if you intend to grow and preserve a lot of tomatoes.

A quick and easy way to process large quantities of tomatoes is with a good-quality tomato strainer, such as Victorio or Squeezo. To convert the tomatoes into strained thick tomato juice, place raw tomatoes, fresh picked from the garden, into the collector at the top, and turn the crank (or, if motorized, turn it on). The seeds and skin are extracted from the juice and easily collected.

We used a Victorio strainer to process tomatoes for use in sauces during many of our initial gardening seasons, primarily when we grew red tomatoes such as Roma and Better Boy. Once we moved on to the colorful heirlooms, we transitioned to preparations where the individual colors could be retained separately. Even when we don’t mind blending colors, our preference has evolved for chunkier-type sauces, so we don’t often use a strainer these days. Still, if tomato juice or smooth sauces are your targets, nothing is quicker to use than tomato-milling equipment.

Processing tomatoes this way confirms the fact that they are as much as 95 percent water. Meaty Roma-type tomatoes, which have a much higher ratio of flesh to seeds and gel, produce the thickest juice. Many of the recipes for homemade tomato juice call for cooking the tomatoes down before putting them through the strainer. The same goes for tomato sauce: if you process the tomatoes raw, the juice will need to be cooked down over low heat or in a low oven to reach the desired level of thickness. The alternative is to cook down the raw tomatoes first, then put the cooked tomatoes through the mill. The juice or sauce produced can be frozen or canned (following the recommended canning guidelines) for later use.

Dehydration is a wonderful tomato preservation method. We adore the flavor of sun-dried tomatoes, particularly as a topping for homemade pizza or as an addition to omelets and frittatas. Anyone who has purchased sun-dried tomatoes, whether dry or packed in oil, realizes that the bits of super-intense tomato flavors come at a relatively high price. Thankfully, producing dried tomatoes at home is quite simple, either on baking sheets in a low-temperature oven, or with a dehydrator. The key to successful oven dehydration is using very low heat, allowing space between the tomato pieces, which are arranged cut side up, and careful monitoring. Patience is also required. Depending upon the moisture level, the thickness of the pieces, and the oven used, the duration of the process can range from 6 to 12 hours.

The type of tomato that you use will have a significant impact on the product. My first attempt at dehydrating Sun Gold cherry tomatoes in the oven produced intense and delicious flavor, but very small fragments, since cherry tomatoes often contain the least flesh of all and have very thin walls. Tomatoes that dry the best, offering an adequate return for the effort, are smaller plum or paste tomatoes, or slices of meaty larger-fruited types. The meatiest tomatoes (those with the least amount of water) make the most substantial dehydrated product.

The tomato pieces may be seasoned or processed plain. Once dried, they can be stored as is, in oil, or frozen, but it is important to follow any specific guidelines for storage on whichever recipe that you follow, to ensure you don’t end up with spoiled product.

If you have a dehydrator, the process for making “sun-dried” tomatoes is even easier, because you don’t need to tie up your oven for long periods of time. By simply following one of the recipes available in the booklet that comes with your dehydrator, you will have a nice yield of delicious tomatoes after eight or more hours of processing time. Be sure to monitor the tomatoes closely toward the end, to achieve the desired consistency.

The idea of canning vegetables hits different people different ways. If you grew up on a farm, and garden and harvest chores were a major part of your early life, the thought of canning may be one you choose to not revisit. If you are a busy person who can barely find time to make an occasional home-cooked meal, the time-consuming nature of canning could seem like just a bit too much bother. But if you’re trying to become more self-sufficient, if you love to cook, or if you become depressed at the end of the gardening season by the loss of all the wonderful flavors, canning may be just the thing to bring a bit of that summer experience into the cold, dark months of late fall and winter.

When we first started canning tomatoes, we bought the bible of canning — The Ball Blue Book. The book says that it takes about 25 pounds of tomatoes to prepare seven quart jars of processed tomatoes. We discovered that 25 pounds doesn’t seem like all that much when you look at the parade of tomatoes lined up on the counter in the peak of the season, but once the tomatoes are prepped into a large bowl, awaiting transfer into the jars, the quantity seems overwhelming. Then, once you actually open up a finished quart jar of tomatoes, there’s some disappointment at how small an amount it seems to be. This is when you question the wisdom of undertaking the canning ritual at all.

Make no mistake — the effort that goes into making that seven-quart batch is not insignificant. Of course, the whole canning process can be quite fun, especially if you can share it with someone and divide out the particular tasks. (My wife and I have become quite proficient at successfully canning without any major collisions or strife!) And, for me, there is nothing like grabbing a colorful quart jar of mixed heirloom tomatoes for a favorite recipe in the dead of winter.

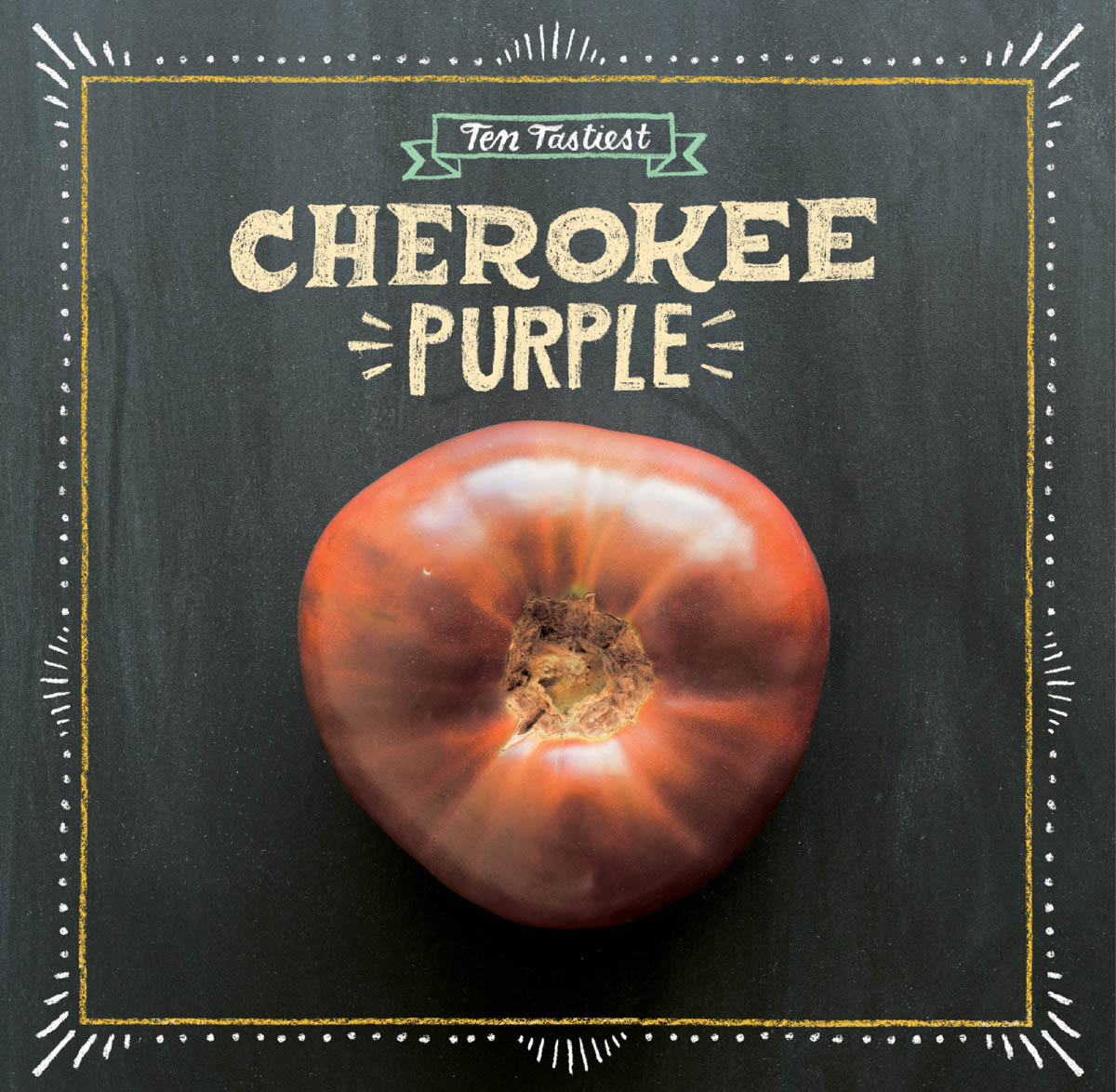

Cherokee Purple defines the ideal intersection of sweetness, tartness, depth, and texture. It is a tomato lover’s tomato, finding a home in salads, on sandwiches, or just sliced into thick slabs. Cherokee Chocolate and Cherokee Green share all the wonderful flavor aspects of this tomato, with the added benefit of having distinctly different colors.

Roasting your own tomatoes creates a sauce with amazing flavor and quality — especially compared with any sauce you’ll find at the grocery store — and the ease of preparation is just plain silly. All it takes is a couple of large roasting pans and any seasonings you’d like to add (we like to roast ours with peppers, onion, and garlic). Once the sauce is done, you can either freeze or can it. The culinary beauty of roasted tomato sauce is in its intensity and complexity; roasting brings out deeper, richer flavor elements you won’t find in sauce made on a stovetop.

Though we love using our roasted tomato sauce the day we make it, the true value is in incorporating it into recipes long after the garden is done. Of course, we love it ladled over cooked pasta, but we enjoy it even more when combined with eggplant. Because of the prolific nature of eggplant when grown in containers, we are often overwhelmed and needed an easy way to preserve it for winter use. By simply peeling eggplant, slicing into slabs, dipping into beaten egg and milk, dredging in bread crumbs, and baking on cookie sheets at 400°F until browned, the excess eggplant harvest can be squirreled away in freezer bags and popped out at a moment’s notice for a great off-season meal. We use the baked, breaded eggplant slices in two ways with our roasted sauce. They provide the perfect layers for a traditional eggplant parmesan (alternating tiers of the eggplant with mozzarella cheese and the sauce). Even easier (and lighter) is simply placing the frozen rounds on a cookie sheet and crisping in a 400°F oven; they then serve as a bed for cooked spaghetti, over which the hot roasted tomato sauce is ladled.

We are avid canners. Though we started with the Ball Blue Book and still follow its major principles and steps, we’ve made a few changes. Since we don’t mind seeds in our canned tomatoes, we don’t go to extremes to remove them all. I also combine seed saving with tomato canning, so most of the seeds end up fermenting in cups instead of in the jars of tomatoes, anyway. We also don’t mind tomato peels in our cooking, so we don’t go to the trouble of removing them when we’re canning.

Whichever recipe you choose to follow, there are a couple of critical steps. You must thoroughly wash the canning jars, lids, and bands to avoid contamination. It’s also important to warm up the jars before you fill them with hot tomatoes, so that the jars don’t crack. We fill the canning jars with water just off the boil while we do our prep work.

Once the quarts are processed, you will find that the tomato solids rise to the top and a layer of clear liquid forms. This is a completely normal testament to the fact that tomatoes are mostly water. The more solid tomatoes you use for the canning process (such as Roma types or the heart-shaped varieties), the less liquid will form. We find that canned tomatoes keep their quality and are safe to eat for up to a year or more. One thing is certain: once you realize how delicious and versatile these tomatoes are, you will never be able to can enough.

The first time I don’t plant Mexico Midget in a large container in our driveway garden may be when my wife, Susan, decides to put me in the doghouse. If it were possible to squeeze the rich, complex flavor of the large beefsteak-type tomatoes into a package the size of a pea, Mexico Midget would be the result. Though it is not all that well known or widely grown, it is one of the most sought-after varieties with my seedling customers and friends. This truly addictive, luscious variety proves that great things can indeed come in tiny packages.

The best time to save seeds from your open-pollinated tomato varieties is when the first tomatoes ripen. I use the first ripe tomatoes for seed saving to reduce the chances that the bees will have worked the flowers and cross-pollinated the seed in the tomato. (See here for more on isolating flowers for the purposes of seed saving.)

Tomatoes that are in edible ripe condition are best, allowing for the pairing of seed saving with eating, cooking, or preserving. Since the genetic material in every seed on every tomato of a particular plant (as long as it is a stable, non-hybrid variety) is the same, it isn’t necessary to use the most perfect specimens on a given plant. (The single exception to this is if the bees that visited the flower cross-pollinated it with another variety; seeds in that specific tomato would produce a hybrid of the two varieties.) The most important thing to watch for is that the tomatoes on a given plant are true to type — that they match your expectations from either the description or past experience.

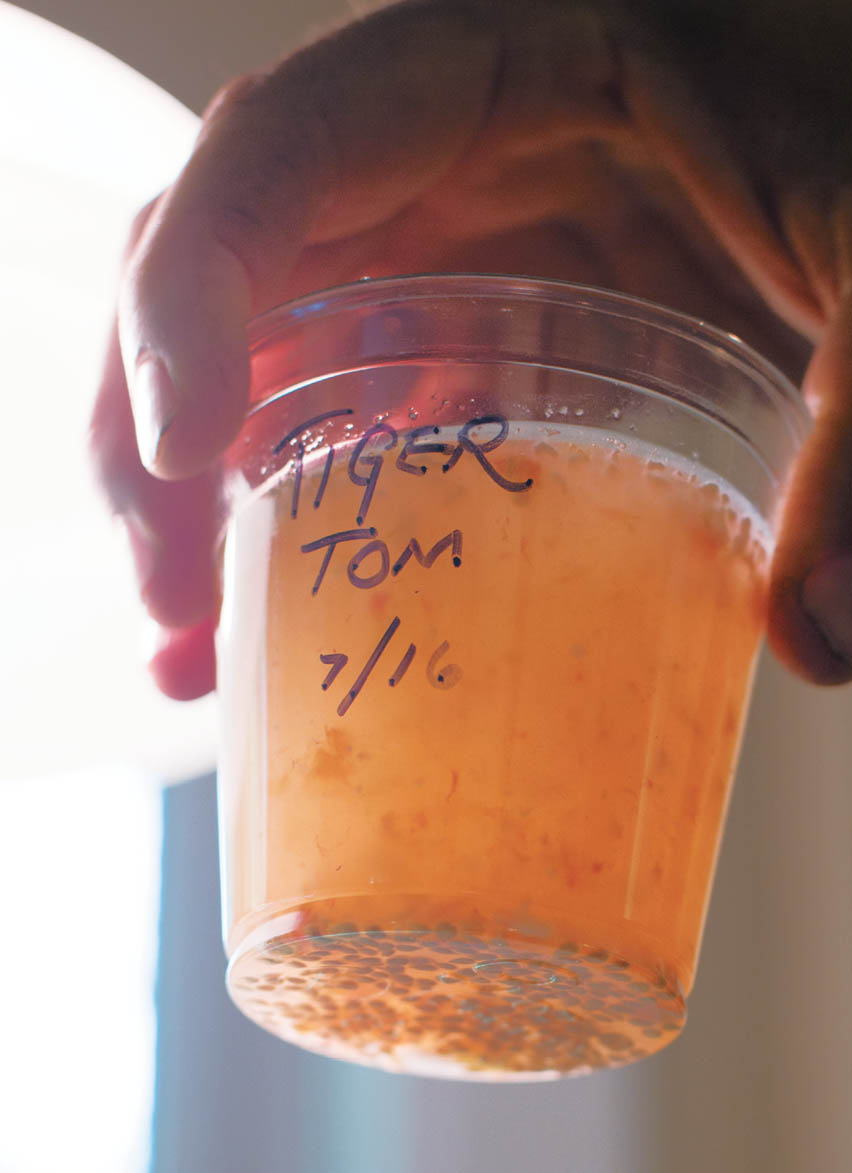

When you’re harvesting ripe tomatoes for eating, be sure to think about seed saving, too. I carry a permanent marker with me whenever I harvest from the garden. After wiping any moisture off the harvested tomato that I intend to save seed from, I jot down the name or reference number directly on the tomato. Later, after the picking is done, my family knows that any tomato with writing on the shoulder near the stem attachment spot is reserved for seed saving. Cherry tomatoes are too small to write on, so I collect them in a plastic cup and write the name of the tomato directly on the cup.

Seed saving is so simple, yet there are also many differing opinions on best practice. Here are the three general ways to save tomato seed:

This is a very simple way to save small quantities of tomato seeds. Cut the ripe specimen tomato in half and gather some of the seeds. You may wish to put them in a sieve and rinse them a bit, pushing the mass against the side of the sieve to clean off as much of the pulp as you can. Either way, spread the seeds thinly, in a single layer, on an uncoated paper plate, a piece of newspaper, or paper towels. Over a week or so, the seeds will dry and adhere to the drying surface. Peel off the seeds and store them as described in Storing Seed.

There’s no doubt that this method is widely used because of its simplicity. In my early years of seed sharing among SSE members, I often received samples of seeds folded into homemade paper packets, which contained small samples of seeds stuck to bits of newspaper, napkins, tissues, or paper towel. One issue with this method is that any diseases on the seed surfaces that are typically removed by fermentation would carry through to the dried seeds. If you’re saving large quantities of seed, there is also the cosmetic issue of paper bits stuck to the seeds (though this won’t cause problems with germination).

I find fermenting tomato seeds easy and effective, though a bit odiferous. The advantage is that it helps remove any pathogens on the seed surface, and below or in the surrounding seed gel. The seeds end up clean, attractive, and easy to package and store.

Fermenting also removes the natural germination inhibitor that coats tomato seeds, leaving the seeds vulnerable to germination. That’s why it’s important to limit the amount of time the seeds are fermenting; otherwise, you would end up with sprouted tomato seeds.

Armed with your perfectly ripe non-hybrid/heirloom tomatoes, you are ready to start your seed saving. Beware, however, that during the seed-saving process, mix-ups or errors could be introduced in many places. Consider this another plea for good documentation and careful discipline so that future tomato mysteries can be minimized.

Typically, when I have a quantity of tomatoes that are ripe and ready for not only seed saving but processing, I arrange them by variety and work on my kitchen counter with a cutting board, my knife, a big bowl, cups, a writing utensil, and my compost bin handy. Here is my seed-saving procedure:

Some swear by this relatively new method of seed saving. The main ingredients are trisodium phosphate (TSP) and bleach. Follow How to Save Seeds Using the Fermentation Method up to step 2; you will have the labeled cups of tomato pulp and seeds. Add a 10 percent TSP/water solution to the seeds and pulp until the cup is approximately three-quarters full. Let the seeds soak in the TSP solution for 15 minutes, which will dissolve the gel and remove any pathogens. Pour off the top material and sieve and rinse the seeds, then return them to the cup. Add a 10 percent bleach solution to the seeds until the cup is about one-quarter full, and soak them for one to two minutes. Sieve once more, and use hot (120°F) water for the rinse. You are then ready to scrape the seeds onto the plates for final drying.

The main enemy of tomato seed is moisture. Any seed storage option should take this into consideration. The other interesting thing I’ve learned about tomato seed is its surprising longevity, which is not something you would know if you read many commercial seed catalogs, whose success is based on bringing people back to purchase seeds each year. Over the years, I’ve stored my tomato seed in screw-top glass or snap-top plastic vials, where it has experienced all sorts of temperature changes as we moved about. Even given that rough treatment, I’ve found that my saved tomato seed germinated very well even at 12 years old, and occasionally up to 14 years.

Seeds can be stored in a variety of ways. Glass or plastic vials and manila coin envelopes are my methods of choice. If your storage area is humid, airtight containers such as vials are best.

Tomato seeds will remain viable even longer if stored in the freezer, in a vial with a small packet of silica gel. The main caution for using seeds stored in the freezer is to allow the seed containers to reach room temperature before opening them. Otherwise, unwanted moisture from the air will be drawn into the containers and negate the work that was done to enhance the seed life.

I’m a very frugal gardener, and fortunately all of the stages of gardening can be done on any budget. My preference is to keep things as simple and inexpensive as possible, and that extends to seed storage. I’ve moved from the glass vials (which are not inexpensive) to plastic vials (which are less expensive but still a significant cost, especially when saving a few hundred varieties each year) to small manila coin envelopes, which I don’t seal but just store upright in my office. Since we have a heat pump, temperature and humidity move in quite a narrow range, so this method works just fine.

One critical final part of the seed-saving process is documentation; a good system is very helpful in terms of locating the seeds you save, and ensuring that you know exactly what they are. I take it even further and aim for knowing each saved seed’s genealogy, which helps me determine possible reasons for any unexpected surprises.

There is a special set of tomatoes that marked my entry into the wonderful world of heirloom varieties, and each played a role in converting me from exclusively hybrid to mostly non-hybrid types. Though they are not necessarily the best flavored, most colorful, or most unique, my tomato interest could not have evolved to where it is today without obtaining these varieties early on. Each is a tomato that was special enough to be maintained and passed on, and each possesses its own distinctive story.

In 1989, the postman delivered a letter to me from Brenda Hillenius of Corvallis, Oregon. Inside was a letter written on delicate onionskin paper along with a small packet of seeds. The variety, Anna Russian, was given to Brenda’s grandfather, Kenneth Wilcox, some years before by a Russian immigrant whose family sent him the seeds.

I grew Anna Russian for the first time in 1989 and was immediately enthralled. The plant itself was rather skinny, unimpressive, and not particularly vigorous, and it required frequent support to the proximal stake to remain upright. (All heart-shaped varieties tend to show this scrawny growth habit, but Anna Russian took the cake.) What was impressive, however, was the beauty and flavor of the tomatoes. Starting to bear quite early, Anna Russian produced nearly 20 pounds of fruit at an average weight of about half a pound each. Unlike many heart-shaped varieties, which can be quite dry, solid, and bland, Anna Russian was full of juice, with a succulent texture and full-bodied, absolutely delicious flavor that had all elements — sweetness, tartness, intensity, complexity — in perfect balance. This pink heart-shaped tomato is one that I return to often for reliable yields of superb fruit.

I was sure to save plenty of seeds that first year I grew it, and I listed it in the SSE yearbook. Many SSE members requested seed, all seemed to love it, and it found its way into seed catalogs, thus this wonderful tomato with a charming story is now widely available for gardeners.

One of the joys of becoming an SSE member was the opportunity to interact with real tomato enthusiasts via handwritten letters delivered in the mail, a format that is rapidly becoming obsolete. Among my first tomato variety requests as an SSE member was a set of tomatoes from Jim Halladay of Pennsylvania. Mr. Halladay sent me Tiger Tom in 1987, and it quickly became a flavor favorite. Jim noted that he obtained Tiger Tom from Ben Quisenberry (of Brandywine fame), and that Ben got it from a Czech tomato breeder. With its lovely striped appearance and snappy, tart flavor, Tiger Tom is a premier salad tomato that I continue to grow regularly.

The excitement I experienced when growing tomatoes of different colors for the first time is best represented with the variety Ruby Gold. It is one thing to read a description of huge tomatoes that end up as blends of yellow and red; it is quite another thing to watch it happen. I obtained it in 1987 from SSE member John Hartman of Indiana. Ruby Gold was first offered to American gardeners in 1921 by the John Lewis Childs seed company of New York. It appeared to go out of favor and was rediscovered at a West Virginia market in 1967 by Ben Quisenberry. Through the years, the same tomato seems to also have owned the names of Early Sunrise and Gold Medal.

When I received my first SSE yearbook in 1986 and the world of heirloom tomatoes presented itself, it was tempting to sample as many unusual colors as possible. As I read through descriptions, Bisignano #2 stood out as a red tomato worth trying. Supposedly, the tomato originated from Italy, and it was featured in the garden of a Mr. Bisignano, a finalist in the 1984 Victory Garden competition.

Unusual in that the fruit shape varies widely on any given plant (from oblate to nearly heart shaped), Bisignano #2 possesses an intense, truly deep tomato flavor that is at home in a salad, on a sandwich, or as a main component of sauce. It has been a favorite tomato for nearly 30 years.

Leaping out of the soil and producing vigorous seedlings with enormous potato-leaf foliage, Polish impressed me in every way. My initial experience growing Polish provided a valuable lesson about tomato colors. Described by long-time SSE member Bill Ellis as “brick red,” it was actually a pink variety, having clear skin over red flesh. The flavor was just breathtaking, and Polish became the first of the knockout heirloom varieties for me. Though through the years I’ve located tomatoes that are the equal of Polish in flavor (including what I assume to be the authentic version of Brandywine), it will always hold a special place in my tomato-themed heart for the way that it opened my eyes to a completely new world of gardening and eating.

Reading of a tomato that was actually a wedding gift was intriguing; that it was white made obtaining and growing it irresistible as I set off on my heirloom tomato exploration. The full tomato name appears to be Kentucky Heirloom Viva, named by H. Martin of Hopkinsville, Kentucky, who donated it to the Landscape Garden Center of the University of Kentucky. Viva Lindsey was a friend of the Martin family; Viva was given this tomato, already an heirloom variety, as a wedding gift in 1922 by her husband’s great-aunt. The medium-to-large, nearly white tomatoes have a lovely pale pink blush on the blossom end. The mild, sweet flavor is just lovely, and it is tomatoes such as this, combining unique beauty with a captivating history, that drew me so deeply into heirloom tomatoes.

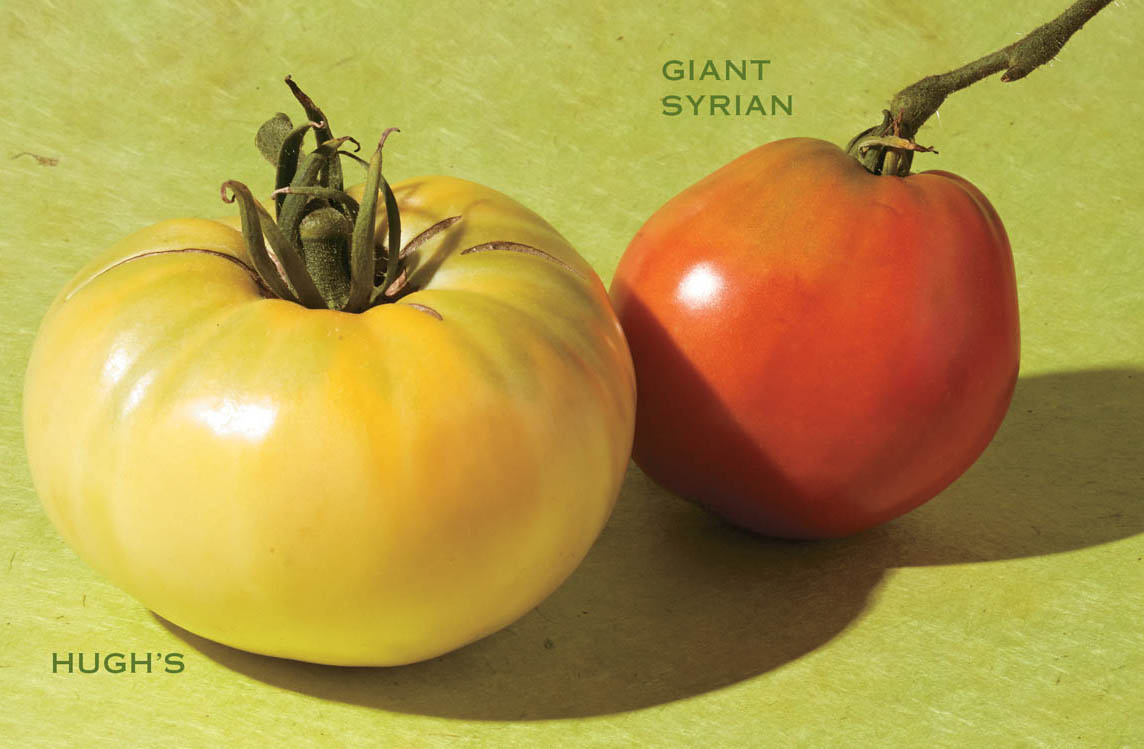

A favorite period of my SSE membership was the early years, between 1986 and 1992, because of the activity and visibility of many of the elderly seed savers whose contributions essentially built the organization. Men such as Thane Earl and Fax Stinnett will always be special in the minds of tomato enthusiasts from those days. Another of those special people is Archie Hook from Alexandria, Indiana. Mr. Hook apparently had a small greenhouse in his neighborhood and provided seedlings for many of his gardening neighbors. One of the first heirlooms I tried was obtained from Mr. Hook, a truly outstanding variety called simply “Hugh” (from his letter), more commonly known today as “Hugh’s.” Mr. Hook indicates that he had this variety from the 1940s. The first time I grew it, 40 pounds of tomatoes were produced on a single plant, most coming in at well over a pound. The color of Hugh’s fruit is very pale yellow, similar to Lillian’s Yellow Heirlooms. The flavor of Hugh’s has varied a bit for me through the seasons, ranging from outstanding and intense to mild and sweet. It’s one of those varieties whose flavor seems to vary more than most, depending on a season’s particular weather conditions.

When I started dabbling in seed swaps through the National Gardening Association magazine (at the time called Gardens for All), I met some wonderful, giving people. Few shared as many heirloom treasures with me as Charlotte Mullens, of Summersville, West Virginia. I already referred to the Mortgage Lifter that she sent me, but my favorites are Gallo Plum and Giant Syrian. Charlotte received the seeds of Giant Syrian from Harold DeRhodes of Ohio, who claimed that his family had grown them for a long time. I was delighted with my initial exposure to this tomato, as it was immense, heart-shaped, delicious, and unusually red (pink is more typical for heart-shaped varieties). Giant Syrian produces amply on very rampant, vigorous vines that show the typical spindly characteristic of just about all heart-shaped types. I will always think fondly of the late 1980s through the early 1990s as a time when there was great sharing of varieties between like-minded gardeners through seed swaps and the SSE. In a way, many were discovering the joy of seed saving and heirlooms at that time, building the foundation for a hobby that continues to grow each year.