British journalist Miles Kington once said, “Knowledge is knowing that a tomato is a fruit. Wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad.” But as clever as that sounds, the lines are now blurred, as we contemplate tomatoes so sweet that they can be made into ice cream or festoon our dinner salads, with strawberries and pears sitting happily alongside the Sun Golds and Mexico Midgets and wedges of Tiger Toms. Knowing exactly what to call tomatoes is not important. What is important is having the ability, through gardening or shopping, to make the most out of such a time as this, when the variety of tomatoes available is essentially infinite. Our journey begins here.

Tomatoes range from perfectly round (globe shaped) to highly flattened (referred to as oblate) — as if someone put one hand on the blossom end and another on the stem end and squeezed to flatten the fruit. They can be oval or egg-shaped (also called “deep globe”), long and slender like a frying pepper, heart-shaped, or even pear-shaped, with a thin neck and bulging bottom. Many of the larger oblate tomatoes have irregularities, creasing, and an overall individuality of form (which to some can veer toward ugliness) that many people associate with the classic shapes of some of the older, heirloom tomatoes.

The round tomatoes range from the size of a pea to that of a softball or grapefruit, and from a fraction of an ounce to 2 or 3 pounds. The flattened, oblate types range from 1 or 2 ounces to 3 pounds or more. Egg-shaped tomatoes start at an ounce and can reach half a pound (larger in rare cases), as do the longer, thinner specimens. Heart-shaped tomatoes range from half a pound to 2 pounds or more. Of course, there are varieties of tomatoes of sizes throughout the extremes noted here. The realm of tomato options seems to grow unabated year to year, as more heirlooms surface and amateur breeders work to fill in any gaps.

Various terms are used to describe the preferred uses of tomatoes by shape. Tiny or small round tomatoes are often called cocktail, grape, cluster, or cherry tomatoes. Such tomatoes are wonderful for salads, omelets, frittatas, kebabs, or pizza toppings. Tomatoes of a few ounces are sometimes known as salad, breakfast, or grilling tomatoes, and any tomatoes that work well on a sandwich — whether half a pound or multi-pound monsters — are often called slicing tomatoes.

Since the late 1800s, the medium-size round tomatoes seem to have been preferred for canning. Prior to that date, though, very large, irregular varieties that originated in Italy and found their way to California were the canning choice. The meaty, elongated, slender tomatoes often consisting of a dense flesh with less juice are favored for sauces or pastes; hence the term “paste tomato.” Finally, many of the large tomatoes, when sliced parallel to the blossom and stem ends, show a dense, meaty flesh with small seed-filled cavities. For years, these have been known as beefsteak tomatoes, a term first used in the late 1800s. The designation has nothing to do with flavor, and everything to do with comparison to the density of a slice of steak.

Each type of tomato — whether juicy, dry, soft, succulent, firm, or meaty — interacts with tasters’ palates in different ways, and one person’s cherished variety could be another’s to toss into the compost heap. This is the fun of tomato tastings. For the cook, part of the fun of creation during harvest time is to match a type of dish with what’s ripe that day.

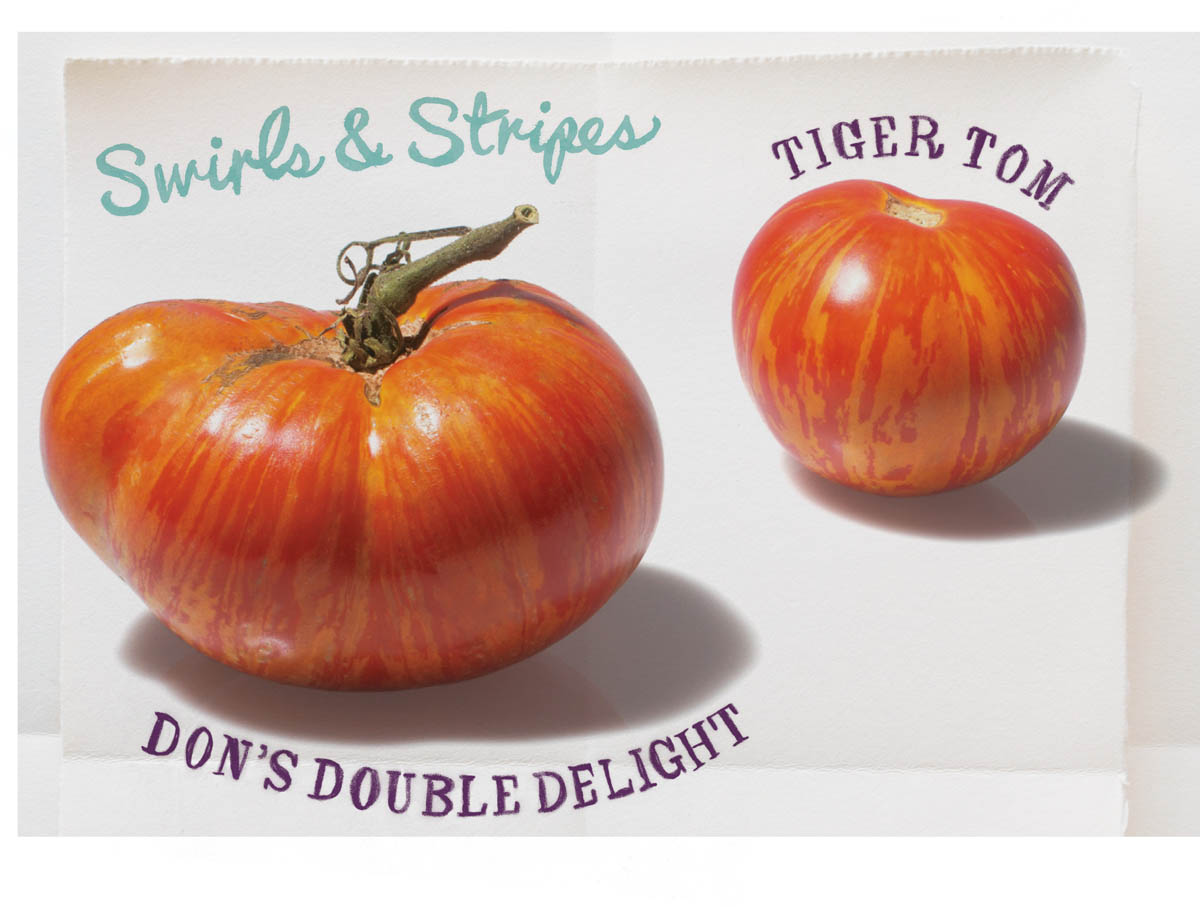

The diversity in tomato shapes and sizes is fascinating, but the real fun arrives when considering the incredible rainbow of color options available in tomatoes today. I enthusiastically tasted my first non-red tomatoes in 1987, when I grew Persimmon (pale orange), Czech’s Excellent Yellow and Lemon Boy (bright yellow), Ruby Gold and Pineapple (yellow with red swirls), Tiger Tom (red with gold zigzag vertical stripes), and Brandywine (pink). Waiting for the fruit to ripen was so exciting, and the beauty of the fruit inspired us to find ways to take advantage of their appearances in our cooking exploits.

Though much of the confusion surrounding tomato colors comes from inexperience, even the most experienced gardeners struggle with factors such as the unclear terminology, personal opinions on what a particular color name connotes, and perhaps just a difference in the ways that some of us perceive and identify color. It doesn’t help that tomato color classification errors are very common in seed catalogs and on gardening websites. Confusion over classification of tomato varieties by color is not recent, and seed catalogs from the very beginning don’t appear to have used standard or consistent terminology.

Another important point about color is that a tomato’s outside appearance is actually the combined effect between skin color and flesh color. In fact, skin color is critical in determining how we classify a tomato, with a single exception (see Green and White). The net effect is that we call a tomato a particular color given what it looks like unsliced. A cut slice of the tomato would often be called something quite different, and there would be a more limited color palette if we categorized tomatoes by their flesh, rather than the color of the uncut fruit.

Finally, many will wonder what the relationship is between tomato color and flavor. It is up to each gardener and tomato taster to reach his or her own conclusions, but to my taste buds, the flavor of each specific tomato variety is distinct (sometimes subtle, sometimes screamingly so), and though some generalizations can be made, so many exceptions exist that it is better to not use color as a guide to tomato flavor.

Red tomatoes represent most people’s idea of tomato color and are therefore the yardstick of comparison for those who have yet to be exposed to the fancifully colored heirloom types. The defining characteristic of red tomatoes is yellow skin color. The effect of yellow skin stretched over red flesh makes the tomatoes appear to be scarlet, the hue of red with just a trace of orange. The flesh of red tomatoes can vary widely, ranging from a rather pale pink to a deep crimson. The combination of yellow skin over red flesh represents dominant gene expression, which explains the relatively large number of red tomato varieties. Red tomatoes typically predominate at larger farmers’ markets, because the red hybrid types such as Celebrity and Mountain Pride are often preferred for field planting and large-scale production.

Representative red tomatoes: Big Boy, Better Boy, Roma, Celebrity, and Big Beef (hybrids); Andrew Rahart’s Jumbo Red, Aker’s West Virginia, and Abraham Lincoln (heirlooms).

If red flesh is covered with clear, rather than yellow, skin, the tomato is referred to as pink (although crimson could be an even more descriptive designation). There are comparatively fewer pink tomatoes because the clear-skinned characteristic is a recessive trait. The pink/red designation tends to be quite confusing for many gardeners, possibly because of the varying abilities to define colors or just inexperience with seeing the differences between the two.

In old seed catalogs, pink tomatoes were often called “purple,” because the types we know of today as closer to true purple (such as Cherokee Purple) weren’t known at the time. With no good comparison, to some early eyes the pink tomatoes, when compared to red ones, looked purple. This can also be seen in the realm of many pink-fruited heirloom tomatoes, such as Pruden’s Purple, which are clearly misnamed as to color.

Red and pink tomatoes can be distinguished only by their skin. The color of the flesh of each type is quite similar.

Representative pink tomatoes: German Johnson, Pink Brandywine, Ponderosa, Eva Purple Ball, and Anna Russian.

One recent tomato phenomenon is the significant increase in the number of black tomatoes, starting in the mid-1990s. What distinguishes black varieties is very deep crimson-red flesh combined with varying proportions of retained green pigment, particularly in the gel surrounding the seeds. Black tomatoes possess a recessive genetic trait that calls for retention of some chlorophyll even after full ripening, resulting in a green-over-red effect. This leads to significantly darker coloration. If the skin color is clear, the apparent color of the tomato is purple, with a distinct darkening at the shoulders. If the skin color is yellow, the apparent color is a burnt mahogany/chocolate brown. Since experience with these two relatively recently occurring tomato colors is still somewhat limited, the error rate in color attribution is high; many purple tomatoes are classified as brown or chocolate, and vice versa.

As with red and pink tomatoes, once purple and brown tomatoes are sliced, their inner appearance is identical. If you wish to take advantage of the distinct difference in outward appearance, it is necessary to ensure that the tomato pieces are large enough and presented so that the skin is easily seen.

Representative purple tomatoes: Cherokee Purple, Black Krim, Black from Tula, Purple Calabash, and Black Cherry.

Representative brown tomatoes: Black Plum, Black Prince, Cherokee Chocolate, and Japanese Trifele Black.

A continuum of hue exists between the palest of yellow and deepest of orange tomatoes, and this is quite a tricky color category to deal with. Tomatoes with yellow flesh covered by clear skin can approach the bright color of a goldfinch or fade to a color closer to ivory. Varieties with yellow skin and yellow flesh range from a pale hue to a deep shade of butter yellow. The ripe fruit color of a particular yellow or orange variety can vary from season to season, or even within a particular season, depending on the temperature at which the tomato ripens. Throw in color terms such as “gold,” and clear categorization becomes problematic. Different people call all sorts of colors “gold,” from pale yellow to a rich near-orange yellow. When the flesh darkens to orange, a clear-skinned variety will become pale orange, similar to a pumpkin, and yellow-skinned, orange-fleshed varieties will appear as a deep, rich orange.

When served sliced, tomatoes in this color category can become quite interesting. Depending on skin color, some tomatoes that appear orange from the outside have bright yellow interiors because of the skin/flesh interaction. Some yellow tomatoes, when sliced, appear to be nearly white. It all makes for great fun when preparing a simple caprese salad in a way that places a rainbow of variety on the plate.

Representative yellow tomatoes: Yellow Pear, Lemon Boy, Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, and Lemmony.

Representative orange tomatoes: Sun Gold (hybrid); Yellow Brandywine, Persimmon, and Kellogg’s Breakfast (heirlooms).

Most unusual in the spectrum of tomato colors are those that exhibit such a pale yellow shade as to be nearly white or ivory, as well as the varieties that remain green when in edible ripe condition. The so-called white varieties have near-white flesh and a clear skin. They often develop a pale pink blush at the blossom end, and when they are very ripe, they take on more of a pale yellow color. This is one area where there does seem to be a relationship between tomato color and flavor. With very few exceptions, I’ve found the flavor of white tomatoes to be quite mild, verging on bland.

Green-fleshed tomatoes can have either yellow or clear skin. I’ve found green-fleshed tomatoes to be almost consistently quite wonderful and among my favorites for fresh eating.

The green-fleshed varieties indicate their ripeness by turning a rich orange-yellow color, which makes categorizing them somewhat confusing. Despite their yellow outward appearance as they hang on the plant, they are classified as green tomatoes because of their ripe flesh color.

The green-fleshed varieties with clear skin provide a true picking-time challenge for the gardener. But these varieties do typically develop a pale pink blossom-end blush and take on a subtle, hard-to-describe color change when ready for eating. The squeeze test works well, too.

Representative white tomatoes: Great White, Snow White Cherry, Dr. Carolyn, White Beauty, and White Queen.

Representative green tomatoes: Cherokee Green, Dorothy’s Green, and Evergreen (yellow skin); Green Giant and Aunt Ruby’s German Green (clear skin).

To complete the remarkable range of tomato colors, some varieties display more than one color when ripe. Tomatoes with yellow flesh swirled with pink or red, both inside and out, are often referred to as bicolored beefsteak types. On rare occasion, the swirled color combination is green with deep crimson, appearing as nearly purple with green shading externally, typified by the variety Ananas Noire. This class of tomatoes is easy to spot even when sliced, because the mix of colors bleeds into the flesh, as well as being apparent externally.

Finally, we come to those varieties that have distinct vertical stripes on the skin. Until recently, the only striped color combination known was red with gold stripes. Recent work now provides us with green and gold, purple and green, yellow and pink, and other variations in between. The visual appearance of the striped varieties is simply stunning. Note that the special striped coloration is a characteristic of the skin and does not bleed through into the flesh. The best way to capture the unique beauty of the striped varieties is by using them whole for stuffing or in large wedges with significant portions of skin attached.

Representative multicolor tomatoes: Ruby Gold, Regina’s Yellow, Hillbilly, and Lucky Cross (bicolored beefsteak types).

Representative striped tomatoes: Green Zebra, Tigerella, Berkeley Tie Dye, Tiger Tom, Vintage Wine, and Copia.

In 1988, I received three small packets of seed, along with a brief but pleasant letter, from Robert Richardson of New York. One of the seed packets was labeled “Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom #1” and contained a local heirloom variety that Lillian Bruce, a gardener from Tennessee, had grown for many years.

Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom is a very vigorous, indeterminate plant with enormous, dark bluish-green, potato-leaf foliage. The fruit are smooth, oblate, and very large (averaging 12 ounces, but often over 1 pound). They ripen very late (105 days from transplant) but are well worth the wait. The color is a very pale yellow with just the faintest hint of pearly pink at the bottom of the tomato (which was especially unique for potato-leaf varieties when I first grew it), and the flavor is outstanding. My experience in 1989 was certainly very limited compared with that of today, but just about all yellow or orange varieties I knew then tended to be very mild, sweet, or bland. That is not at all the case with Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom. I’d wager that a blindfolded tomato taster would conclude that the variety is one of the best he or she had ever tasted, and would likely guess it to be a red or pink variety— certainly not bright yellow.

One surprise, not at all welcomed by a seed saver, is the variety’s dearth of seeds. A typical 1-pound fruit of Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom will likely provide less than 25 seeds. Given the high ratio of flesh to gel and seeds, one might think the texture would be too firm and dry, but nothing is further from the truth: few tomatoes are as succulent and enjoyable to eat. Each year my wife and I eagerly anticipate the days when some slices of Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom are available to feature in our evening meals.

After my initial experience with Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, I listed it in the SSE yearbook. Eventually it ended up in a few seed catalogs, and it has gained in popularity over the years. I’ve also been delighted to discover that it really enjoys our challenging North Carolina weather and does consistently well in our gardens each year.

When Robert Richardson sent me the seed of Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, he also included a variety that he called Lillian’s Red Kansas Paste. All we know about the variety is that Lillian Bruce received the seeds some years previously from someone in Kansas and subsequently shared them with Mr. Richardson. Lillian Bruce considered it the best-tasting tomato in her collection.

This is a tomato that deserves wider recognition. Produced on a tall, vigorous plant with the typical wispy foliage and floppy stems of most paste and heart-shaped varieties, the brilliant scarlet red tomatoes are irregular in shape, tending to oval, but not quite heart-shaped and not quite paste. And unlike typical paste-type tomatoes, they have plenty of juice, lots of seeds, and a full-bodied, rich flavor that makes them a delight in salads and a star in sauces.

If all tomatoes tasted the same, we would still be able to enjoy the wide varieties of shapes, sizes, uses, and colors. But what makes it all the more enjoyable is the amazing array of flavor nuances. To my palate, the most distinctive tomato flavor characteristics are tartness compared with sweetness, flavor fullness compared with blandness, and complexity compared with simplicity. Each of these characteristics is on a continuum as well, which makes the flavor combinations and impacts endless.

Some tomatoes are marketed or described as “low-acid” varieties. Interestingly, a recent study disproved this myth by showing that the acid level in just about all tomato varieties lies within a very narrow range. Tomatoes that taste tarter simply possess less sugar, and those that taste sweeter are higher in sugar, which masks the sensation of acid. Some tomato varieties attack the taste buds in their assertiveness, while others are incredibly subtle, approaching blandness. Very few tomatoes possess perfect balance between sweet and sour, fullness and subtlety, and they can be fairly complex in flavor character. (If it sounds like I am describing fine wine, the analogy is actually quite apt. We find that tomato tastings are just as challenging, enjoyable, and varied as wine or beer tastings.)

Aside from flavor, several factors contribute to the enjoyment level of a particular tomato variety: texture, juiciness, tenderness or thickness of the skin, and relative ratio of seeds and surrounding gel to flesh. I’ve sampled tomatoes with very good flavor but flesh that is watery or has large empty spaces in the seed cavities, which left me with a negative impression of the variety overall.

People often presume that a correlation exists between color and flavor. I’ve attended enough tomato-tasting events and spoken to enough seedling customers to understand that many gardeners believe that red tomatoes have an assertive, acidic flavor. This could be because several of the older red-colored commercial varieties, like Rutgers and Marglobe, have a lower sugar content and therefore strike the palate as relatively tart. These types of tomatoes were the varieties of many people’s youth. Similarly, lots of people think that pink, white, yellow, or orange varieties have a sweet, mild flavor. These are often mislabeled as “low acid” at farmers’ markets. I’ve recently heard black tomatoes described as smoky or salty. If we were to blindfold tomato tasters, would they be able to name the color of the tomato being tasted? I suspect that the answer would be no. Through my years of growing and tasting tomatoes of every color, shape, and size, I can identify as many exceptions as general rules when it comes to correlating color and flavor. Since taste is specific to the palate of the taster, all tomato enthusiasts will have their own opinion on the matter. To me, it’s a great reason to grow or purchase, and taste, as many varieties, colors, and types as you can. The only way to test this hypothesis for yourself is to find or grow the tomatoes to do your own tests.

Which type of tomato to grow — hybrid, heirloom, or non-heirloom open-pollinated — depends on the expectations of the gardener. If your interest is primarily in growing a high-yield food-supply garden and you have no interest in saving seeds, focusing on hybrids is a reasonable approach. If your goal is great visual and culinary variety, open-pollinated and/or heirloom tomato types will provide everything you need — including the daunting task of selecting from thousands of varieties!

A hybrid tomato is grown from seed collected from a fruit that developed from a process known as crossing. Most simply described, pollen from one parent is directly applied to the pistil of another parent. Prior to the cross, the anther cone (the pollen-producing part) is removed from the receiving parent so that the flower doesn’t self-pollinate as it typically would. If the ovary below the pistil swells following pollen application, forming a tomato, all the seeds in that tomato will be identical and are what is known as an F1 (first filial generation) hybrid between the two parents. Tomatoes that come from those seeds will show the dominant characteristics of each parent. Big Boy, created and released by Burpee in 1949, was the first famous hybrid tomato, and its popularity revolutionized the tomato-breeding industry. Recent examples of hybrid tomatoes are Better Boy, Celebrity, and Sun Gold. Often, the goal of creating a hybrid is to involve genetic material that helps a variety overcome tomato diseases.

Hybrids have a reputation for being more vigorous, more disease resistant, and overall, just plain better, wiser choices for the gardener. Often, what gets sacrificed in creating hybrid varieties is the single favorite goal for many gardeners: flavor. My own experience is that not all hybrids fight disease well, and certainly not all heirlooms succumb immediately. There are good reasons for commercial operations to focus on hybrids (such as a more concentrated harvest that works well for machine harvesting, specific disease resistance for a particular area, or smooth, uniform fruit for a particular market) but far fewer reasons for home gardeners to do so. The variety of color, shape, size, and flavor is significantly limited with hybrid tomato choices.

Seeds saved from hybrids will germinate and produce tomato plants that produce tomatoes. What type of tomatoes result, however, is not at all predictable or reproducible. Depending on the magnitude of differences between the two parent varieties, it may not be worth giving up valuable gardening space and effort in growing out seed saved from hybrids, unless you are embarking on a dehybridization process to work toward creating a new variety, or replicating the hybrid itself as closely as possible. (This is discussed in greater depth in chapter 7.)

Also referred to as non-hybrid, open-pollinated tomatoes have stable genetic material, and seeds saved from open-pollinated varieties will (unless cross-pollinated by bees) replicate the parent variety. All heirloom varieties are open pollinated, but not all open-pollinated varieties are considered heirlooms. Open-pollinated varieties may exist unchanged for hundreds of years; Yellow Pear is an example. Or they could be the result of recently discovered mutations, such as Cherokee Chocolate, or recent breeding projects, such as those from The Dwarf Tomato Breeding Project.

An heirloom is an open-pollinated variety that has history and value embedded within its story. The term is used very loosely, since a tomato with the word “heirloom” (or “heritage”) attached to it commands more respect (not to mention a higher price tag in many cases). Often, you will find fairly recent open-pollinated varieties such as Green Zebra listed as heirlooms.

My personal guideline is based on the release date of Burpee’s Big Boy (1949). This event represented a major change in tomato variety development by seed companies. Prior to Big Boy, companies sold open-pollinated varieties; going forward, the vast majority of new varieties were hybrids. Given this, to my thinking, heirlooms are open-pollinated varieties that originated before 1950, whether they came from families in the United States or overseas, or from commercial ventures. This also creates two categories of heirlooms: the true family heirlooms that may have interesting histories and occasionally less-developed backgrounds (such as Brandywine), and non-hybrid, pre-1950 varieties developed and sold by seed companies, such as Golden Queen.

Heirloom varieties are wonderful not only for their variety of colors, shapes, sizes, and flavors, or for the ability to easily save seed and pass them on to others, but for the fascinating histories that seem to be associated with many of them. In some cases — such as Mortgage Lifter — we know quite a lot about the history of a particular variety. In other cases, we know far less than we’d like to, and efforts to learn more are often met with frustrating dead ends. Still, a garden filled with heirlooms becomes a kind of living museum and a great tool for teaching and storytelling.

Those who think of the world of gardening as idyllic and peaceful would be surprised at the level of rancor, disagreement, and misinformation surrounding a simple tomato name: Brandywine. This is a tomato that grows on a very vigorous, tall plant with large potato-leaf foliage. The fruits are large, pink, and oblate and often show unattractive irregularities. Some seasons, Brandywine simply shines, while in others it brings disappointment in terms of yield. However, after growing over a thousand different tomatoes over the years, it is still Brandywine that I think of when I ponder the perfect tomato-eating experience. An authentic Brandywine has an unmatched succulent texture that melts in your mouth. The flavor enlivens the taste buds, with all the favorable components of the best tomatoes — tartness, sweetness, fullness, and complexity — in perfect balance.

Because of its popularity, numerous Brandywine “relatives” have been introduced over the years — some with family names attached (Glick, Pawer, and so on), or different colors (Yellow, Red, White, and Black). It’s not clear whether or how these are actually related to the real Brandywine, and, sadly, we will likely never be able to completely untangle the complicated history of this tomato.

Looking back into old seed catalogs, the only use of the term “Brandywine” was for a tomato created and released by the Johnson and Stokes seed company in the late 1800s. I’ve reviewed color plates of the tomato and it appears to be red, medium-size, and with regular-leaf foliage. This indicates to me that what was known back then as Brandywine is actually what we know of today as Red Brandywine, itself a really fine tomato. When considering the location of the seed company (Pennsylvania), the likelihood of the name originating from the river or town of Brandywine is very good.

There are indeed older tomatoes that carry the same potato-leaf foliage and large pink fruit as today’s Brandywine. In the late 1800s, the Burpee Seed company listed a variety called Turner’s Hybrid, and Henderson Seed Company carried Mikado. A few other seed companies also listed large, pink, potato-leaf varieties with their own particular names. Could it be that Mikado or Turner’s Hybrid was grown and passed around through the years, finally becoming renamed by someone in the Midwest as Brandywine? Anything is possible.

My source for the wonderful Brandywine that I began growing in 1988 is seed saver Roger Wentling from Pennsylvania. Roger obtained his version directly from Ben Quisenberry, a legendary seedsman whose story is well documented by the Seed Savers Exchange in Seed Savers Exchange: The First Ten Years, 1975–1985. Ben claims that he obtained the tomato from Dorris Sudduth, and that the tomato was in her family for many years.

A listing in a late 1800s Henderson catalog shows the release of a new variety named Shah, a large, deep yellow variety with potato-leaf foliage, as a “sport” or mutation or selection from Mikado. Some tomato enthusiasts simply assume that Shah is a white tomato. My conclusion, rather, is that what was known back then as Shah is very much like, if not a direct relation to, what we grow today as Yellow Brandywine.

This is a recent release by the Tomato Growers Supply Company. I grew it the first year that it was available, and it proved to be unstable, providing both regular-leaf and potato-leaf plants. Since its release, gardeners who purchased seed carried out selection work; I now have a potato-leaf selection that produces a very good medium-size purple tomato. The relationship between Black Brandywine and Brandywine is unclear.

The growth habit of tomatoes is quite important to the planning process, especially if your ability to grow tall, sprawling varieties is confined for various reasons, whether because of physical limitations or space or garden location considerations. There are, of course, nuances and subtypes, but for the purposes of this book, describing the three main types — indeterminate, determinate, and dwarf — covers the vast majority of tomato types typically available.

This class of tomatoes is by far the most common, and its members grow upward and outward continually until killed by frost or disease. Indeterminate tomatoes have a central main stem from which side shoots, or suckers, grow at a 45-degree angle outward from the attachment point of the leaf stems. In turn, each sucker or side shoot acts as an additional main stem and produces its own side shoots. The central stem of an indeterminate tomato, if vertically staked and tied, will easily exceed 10 feet by the end of the growing season. Flowering clusters appear at varying intervals along the main stem and side shoots, ensuring continual fruit potential until the plant dies; this allows for continual and extended harvest throughout the growing season. Another important characteristic of indeterminate varieties is the relatively high ratio of foliage to fruit, and all of that added photosynthesis means a significantly higher flavor potential when compared with determinate varieties. There are many options for supporting and pruning indeterminate tomato varieties (see chapter 4). Well-known examples of indeterminate tomatoes are Cherokee Purple, Sun Gold, and Better Boy.

Indeterminate varieties, when supported, will grow upward and outward until killed by frost or disease, leading to potentially huge and unruly plants.

Determinate varieties are far less common than indeterminate varieties; the gene that produces determinate growth habit didn’t appear until the 1920s. Determinate varieties look identical to indeterminate varieties as young seedlings, with the same stem width and foliage shapes and textures. There is a genetic component, however, that signals an end to vertical growth, emergence of flower clusters at the end of flowering branches, and massive fruit set over a very concentrated time span. This leads to a very narrow window for fruit ripening, which makes determinate varieties very attractive for commercial ventures that benefit from picking the fruit in just a few rounds of harvest. Because of the way the flowers appear, any pruning of this type will significantly reduce yield. In addition, the very high ratio of fruit to foliage means less photosynthesis; as a result, the vast majority of determinate tomato varieties have less flavor intensity and potential than indeterminate varieties (though there are always exceptions). Because of their compact growth, determinate tomato varieties are perfect for container gardening and caging. Well-known examples are Roma, Taxi, and Southern Night, as well as the Mountain series of commercial hybrids.

Determinate tomatoes, such as Roma, top out at 3 to 4 feet tall and are well controlled by cone-type tomato cages.

This rather unique class of tomatoes is largely unknown to most gardeners, although its profile has been raised recently from the efforts of our Dwarf Tomato Breeding Project. Dwarf tomatoes predate determinate varieties by decades, but very little development work seems to have taken place with them. They are defined by very specific and unusual growth habits. As young seedlings, the stems are very thick and far shorter when compared with those of indeterminate and determinate tomato seedlings. They retain this characteristic throughout their lifetime, behaving like slow-growing indeterminate tomatoes. The foliage is very dark, nearly bluish green, and quite crinkly looking; the term for this is rugose. The ratio of foliage to fruit is quite high, meaning that dwarf varieties possess a greater potential for excellent, full flavor than determinate varieties.

Prior to the advent of our Dwarf Tomato Breeding Project in 2006, the number of dwarf tomato options was limited to just a handful of old, historic varieties such as Dwarf Champion, along with a more recent creation, Lime Green Salad. As of 2013, the Dwarf Project has added another 17 varieties to the mix, and many more are yet to come.

Dwarf tomatoes are able to thrive in containers as small as 5 gallons. They top out at only 3 to 5 feet by the end of a long growing season, which removes the need to stake and deal with rampant vines. They can also be used in close-planting schemes in the garden, raising the yield potential per square foot. Among the new and exciting dwarf tomato releases are Dwarf Mr. Snow, Dwarf Sweet Sue, Summertime Green, and Rosella Purple. The Dwarf Tomato Breeding Project is described in much greater detail in chapter 7.

Dwarf tomato varieties behave like indeterminate varieties in fruiting but grow vertically at about half the rate. They are perfectly happy in 5-gallon containers and are very easy to control with short stakes or cages.

Tomato leaf shape is not so much a parameter for planning as basic information to enhance understanding of the genetics of tomatoes, and it provides one additional characteristic used to distinguish varieties. Most people who grow tomatoes easily recognize “regular-leaf” foliage, with its characteristic toothed edges. This is a dominant trait that is represented by the vast majority of tomatoes, including Better Boy, Sun Gold, Celebrity, Roma, and countless others.

Knowing which type of leaves a particular variety should exhibit can help in spotting crossed or mixed-up varieties in the garden. Most tomato varieties have regular leaves with serrated edges. A few well-known heirlooms, such as Brandywine, show the recessive potato-leaf foliage (which is smooth-edged). Dwarf tomatoes have very dark blue-green, crinkly (rugose) leaves, which appear in both regular- and potato-leaf variations. Heart- and paste-shaped tomatoes tend to have droopy leaves. Wild types, such as Mexico Midget, have very small, finely divided, delicate foliage.

Regular-leaf foliage; potato-leaf foliage; rugose potato-leaf foliage; small, fine foliage (typical of wild types); wispy foliage (typical of heart-shaped varieties; rugose regular-leaf foliage).

Potato-leaf foliage is far rarer. Leaves of this type have smooth margins, with a strong resemblance to the foliage of potato plants (hence the name). This type of foliage is a recessive trait. An easy way to test the success of seed saving with regard to purity is to examine seedlings grown from potato-leaf plants that were themselves grown adjacent to regular-leaf varieties. Any regular-leaf plants that show up during germination will most likely signify an insect-induced cross. It is interesting to note that even though potato-leaf foliage is relatively rare, many famous and delicious heirloom varieties, such as Brandywine and Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, have this type of foliage.

By far, most tomato varieties will have serrated or toothed leaf edges, which is the dominant foliage trait. They are known as regular-leaf varieties.

Rugose foliage is specific to dwarf tomato varieties. Dark bluish-green, rugose foliage is highly folded and crinkled, and particularly lush and attractive looking. Rugose foliage can have either the regular (serrated) or potato-leaf (smooth edge) shape. Such foliage makes the dwarf tomatoes particularly striking plants.

Tomato foliage with smooth edges exhibits a recessive trait known as potato-leaf foliage, since there is a resemblance to the leaf shape of potato plants.

Cherokee Purple came to me as an unexpected gift one day in 1990. It arrived in the form of a letter and packet of seeds from John D. Green (he calls himself “JD”) from Sevierville, Tennessee. He could not have imagined what would happen after I grew the seeds he so generously sent. All we know of the actual history is that JD’s neighbor shared the seeds with him, and that they descended from a purple tomato given to the neighbor’s family by Cherokee Indians about a hundred years ago. As is often the case, I wish I had spent more time asking Mr. Green more about the background of the tomato — the neighbor’s name, for example.

The seeds arrived in time for me to include a plant of the yet-to-be-named “purple” variety in my garden that year. I loved the story that JD told but was skeptical about the color designation; all known tomatoes up to that date with “purple” as a descriptor ended up being pink. Also, remarkably, my garden that year contained Black Krim, the very first “black” variety.

The unnamed purple and Black Krim were definitely among the most interesting varieties I grew that year. To my amazement, ripening brought forth a color that I’d never seen before: a deep, dusky rose color that shaded to nearly true purple at the shoulders. Both the purple variety from JD and the Black Krim showed the same color. I was very excited to be observing something quite new in tomato color; of course, there has been a veritable explosion of “black” varieties since the early 1990s.

Perhaps those two new varieties looked the same, but when sliced and tasted, they were as different as could be. Where Black Krim had a distinct absence of sweetness — in fact it tasted quite flat and lifeless to my wife, Sue, and me — Cherokee Purple exploded in our mouths in a symphony of flavors and nuances. We loved it (and do to this day). Clearly needing a name, I considered the brief history proposed by JD and named it Cherokee Purple, also listing it in the upcoming SSE yearbook and sending a sample to Jeff McCormack of the Southern Exposure Seed Exchange. Jeff called the following autumn and related to me his admiration for the flavor, but also his concern about whether the public would accept such an unusual color “resembling a bruise.”

Years have passed and it is clear that the unique color of the “black” tomato varieties, with the genetic disposition to retain some of the green of chlorophyll upon ripening (thus leading to the deep crimson flesh color and dusky, purple-shaded outward appearance when viewed through the clear skin), has been enthusiastically accepted by gardeners and chefs everywhere.

I’ve spoken to Mr. Green through the years, and he is excited about how popular Cherokee Purple has become, and the last time he and I spoke, he still grew it annually. Unfortunately, he couldn’t shed any additional light on the history of the tomato and wasn’t able to provide the name of the neighbor with whom the Cherokee Indians of the area supposedly shared the seed. This is not an unusual aspect of heirloom tomato stories; we frequently have tantalizing tidbits, but attempts to dig further lead to dead ends.

Cherokee Chocolate In 1995, I was growing a number of Cherokee Purple plants from saved seed. I noticed something unusual about the way the fruit on one particular plant was coloring up as it approached ripeness. Though possessing the same darker-than-typical hue of the “black” varieties, the tomatoes showed something completely different: rather than the dusky rosy purple hue, the ripe outward appearance was more like a brick red or mahogany, and it was just beautiful to behold. The plant habit was exactly the same as that of Cherokee Purple, as was the size and shape of the fruit. In fact, when the first ripe fruit was cut, in its internal structure and color — indeed, even its flavor — it was identical to Cherokee Purple. Clearly, the differing characteristic was the skin color. In this new find, a yellow skin over the dark interior was responsible for the unique chocolatey color.

There were two possible causes for what I observed. If I was fortunate to have planted a seed with genetic material possessing a mutation for skin color, from clear to yellow, seed saved from the newly colored tomato would predictably produce the chocolate “form” of Cherokee Purple. If, instead, the seed I grew was from a fruit resulting from a bee-produced cross pollination, there would be an array of possibilities in the fruit grown from seed saved from the brown fruit. The following season I was delighted to find that all plants produced from the seed I saved from the uniquely colored fruit produced the chocolate-colored variant. I was very lucky to have grown that seed, and a new variety was born, which I called Cherokee Chocolate.

Cherokee Green The story continues, but in an even more unusual way. After I listed Cherokee Chocolate in the SSE yearbook, a seed request came in from a tomato enthusiast named Darrell Merrell, well known in Oklahoma as “The Tomato Man.” Darrell ended up growing my seed, obtained the expected brown-colored fruit that now defined Cherokee Chocolate, stated how much he enjoyed trying out this new variety, and sent me some seeds that he saved. I grew some of those seeds in 1997.

Upon looking over my tomato patch that year, I saw something unusual going on with one of the Cherokee Chocolate plants grown from Darrell’s seed. While all of the other tomatoes in the garden were turning their expected ripe colors, that one plant set lots of tomatoes of the right size and shape, but they were not turning chocolate — or purple, or anything else for that matter. When I looked closely, they did seem to be getting a rather unusual and unexpected yellowish cast. I squeezed a few of the fruits and was surprised to find that they were dead ripe. Picking one of the fruits and cutting it open completed the surprise and brought my delight. It was as green as could be, but one taste told me that it had the same scrumptious flavor shared by Cherokee Purple and Cherokee Chocolate. So, once again, I was faced with a mystery and a problem to solve.

Like Cherokee Chocolate, Cherokee Green has yellow skin, but its flesh color shifted from red to green. If the shift came from a genetic mutation, it would last through successive generations. If it came from an inadvertent cross, other colors would start showing up immediately. The results here are not so clear-cut. Over time, most of the people I’ve shared Cherokee Green seed with did get the green flesh and yellow skin; however, some occasionally found other colors in the mix. It could just be that we are observing an instance where selection in a cross for a recessive trait, such as green flesh, is easier to stabilize in less generations of trial. In the future, I hope to get a better handle on Cherokee Green in terms of confirming whether it is indeed from a cross or a mutation.

Whether it was initially a cross or a mutation, through years of growing, seed saving, and selection, it is now a stable, excellent open-pollinated variety. In a way, both Cherokee Chocolate and Cherokee Green are examples of how new varieties have been identified, shared, and stabilized throughout tomato history.