There are countless ways to grow tomatoes well. Rather than tell people what they must do, my preference is to share what has worked well for me, and then see what I can learn from others. My own gardening practices evolve over time; each season I learn new things. Many of the methods I employed living in Pennsylvania had to be abandoned for my Raleigh gardens because of different weather, soil, location, and tips I picked up through the years.

Before raised beds, self-watering containers, and driveways full of pots, I suspect most people went into the yard, turned over a big rectangle of lawn, and created a garden. This is the way I grew tomatoes for many years, in rows or hills in a big patch of fenced earth that I enriched each year with additions of compost (or, even better, mushroom compost, which is well worth seeking out). I dug holes, planted seedlings, and pounded stakes into the ground to provide vertical support, and the result a few months later was the eagerly anticipated harvest. Since most of us plant tomatoes this way and have for years, I will focus on what I think of as the most important factors for success using this tried-and-true method.

The leaves of autumn provide a perfect layer of mulch for the winter, slowly feeding the soil underneath and holding down weeds. Simply rake the leaves aside in spring to dig planting holes for the tomatoes.

Our family’s first garden was in New Hampshire, in a college community plot that was created and maintained for students. It was wonderful — fenced, turned over each year, and given an annual, pre-season application of composted manure. Little did we realize how lucky we were to be able to easily stick a shovel into the rich, dark soil and not find rocks and clay deposits.

We were spoiled early on, that’s for sure. All of our subsequent gardens had to be hand-dug. It’s not hard for me to remember how much work it involved: cutting squares of sod, turning them over, chopping into smaller pieces, and finally tilling it all in. Our early gardens on any given patch of ground were very successful because of the plethora of untapped nutrients and absence of soilborne tomato diseases. We lived then in an area (west of Philadelphia) that received hard freezes each winter, so despite a limited opportunity to rotate the tomatoes into new areas of the garden each year, we saw no significant drop off in productivity or increase in disease issues.

Our experience in Raleigh has been quite different, with a yard that seems to ooze impermeable red clay and rocks. Aside from being a digging and drainage nightmare (issues we found ways to cope with effectively), the lack of a winter freeze, and therefore lack of a good mechanism for killing some stubborn pests, means declining success annually; it is this that caused me to move most of our tomato growing to containers. Our experience reinforces the need for each gardener to understand the local advantages and challenges of his or her own particular climate and soil conditions.

The seedlings are ready to be planted, and you are already dreaming about what to do with your harvest to come. It is important, however, to take a deep breath, step back, and do some mental checks to determine the right time to plant. Though well-hardened tomato seedlings are reasonably robust, planting too early presents some real risks, and often no real benefit.

Many enthusiastic gardeners tend to pack too many plants into a given plot. It’s important to sketch out a planting plan that includes sufficient space for each plant to grow. The number of plants you can fit into a garden depends on the types of plants you plan to grow and how you’ll grow them. Choosing dwarf varieties or train-ing plants to grow vertically will allow for the densest spacing. Caging comes next, with the boundaries between plants set by the edge of the cage along with some space to allow for air circulation around the plants. Allowing the plants to sprawl takes up the most room, but of course it is the lowest-maintenance approach. In between are all sorts of variations — such as Florida weave, espalier, Japanese tomato ring, and training plants up extended strings or chains dropped from above (described in The Japanese Ring) — each of which requires different spacing between plants to ensure the best success.

Walk into your garden, dig a hole at least 1 foot deep, and examine the soil structure. If you’re lucky, the topsoil — the layer of dark, crumbly, worm-filled soil at the surface — will be at least a few inches in depth. Under this are the layers of subsoil of varying depths, which could contain rocks and clay. The structure of the subsoil affects the ability of the garden to drain and retain nutrients. Clay soil drains poorly but retains nutrients well; sandy soil, as you might imagine, does just the opposite.

You may find that the topsoil layer is quite shallow, and the clay-filled layer beneath is very dense and difficult to dig into, which poses a real drainage challenge. We didn’t have to dig too deeply in our first North Carolina garden before we hit what seemed like brick material; it had very poor drainage. On the opposite end of the spectrum, you may find little to no topsoil, but simply a thick layer of sand with poor moisture and nutrient retention. No matter what you observe, it’s not difficult to improve the situation for your tomato plants.

After you examine the soil, fill the hole with water (or dig it before a significant rainstorm) and see how quickly it drains. If it empties gradually — within an hour or so — you’re in luck: your soil structure allows for ideal moisture retention. Holes that remain quite full for a day or more indicate trouble and you should seriously consider planting in a different area or creating a raised bed (see Growing in Raised Beds). Water that drains immediately indicates a very porous, sandy substructure; adding compost or leaf mulch will help considerably with the retention of water that your plants need.

Vertically grown indeterminate tomatoes should have 3 feet between plants and 4 feet between rows.

Cage-confined determinate or dwarf tomatoes should have 2 feet between plants and 3 feet between rows.

Sprawling indeterminate plants should have 4 feet between plants and 4 feet between rows. Note that the entire garden is well mulched to ensure that the soil does not come into contact with any plant parts.

Testing your soil for nutrient content (mainly nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus) and pH level will be very informative and helpful, particularly if your garden plot has failed you in the past. Just a year or two of growing most kinds of vegetables in a garden plot is enough to deplete nutrients and necessitate a nutritional boost.

Soil is composed of three main components: clay, sand, and silt. When these three components occur in roughly equal proportions, the soil is said to be “loamy.” When one soil component dominates, conditions can be improved by regularly adding organic matter such as compost.

Soil dominated by clay is sticky when wet and rock hard when dry. Clay soils drain poorly and warm slowly but are often rich in nutrients.

Often a light color with visible particles of mineral and rock and gritty to the touch, sandy soil is easy to dig, drains well, and warms up quickly. Nutrients can wash through easily.

Silt is a granular substance made up of quartz and feldspar, with a particle size somewhere between sand and clay. It feels a bit like flour when it is dry but is quite slippery when wet.

Containing a balanced mix of sand, silt, and clay, loamy soil feels fine-textured and often a bit damp.

The relative acidity or alkalinity of soil is measured in a logarithmic scale called the pH scale, running from 0 (for extremely acid) to 14 (for extremely alkaline). Neutral pH, neither acidic nor basic, has a pH of 7. Tomato roots absorb needed nutrients from the soil when they are made soluble in a slightly acidic environment. So tomatoes do best in a slightly acid soil pH level of between 6.2 and 6.8. Soil that is too acidic will actually be deficient in some critical tomato nutrients, such as potassium and magnesium, because they will have leached out of the soil. If the acid is insufficient (with a pH above 6.5) the nutrients that are present will not be able to dissolve into a state that can be taken up by the plant root system.

The easiest way to adjust the pH of your soil so that it is fit for healthy tomatoes is by applying two simple substances. You can “sweeten” overly acid soil (make it more alkaline) by adding ground or pelletized limestone. You can acidify alkaline soil by adding sulfur. Rather than guessing on amounts, carry out a pH test using your local Cooperative Extension Service and follow the guidance of the results for the recommended adjustments. It is important to note the type of soil as well — sandy, loam, or clay, as described on What’s in Your Soil? — as this significantly affects the quantities of amendments needed to carry out the adjustment. For more about how to alter the pH of your soil, follow the links in Resources and Sources.

The most significant nutritional needs of tomatoes are for nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Most gardeners are familiar with number designations on commercial fertilizers, such as 5-10-5, and this is what the numbers refer to — the relative amounts of N, P, and K. For example, for every 100 pounds of 5-10-5 fertilizer, there are 5 pounds of available nitrogen, 10 pounds of phosphorus, and 5 pounds of available nitrogen, 10 pounds of phosphorus, and 5 pounds of potassium. In general, tomato plants need relatively less N and relatively more P and K.

As an alternative to balanced, mixed (complete) fertilizers, you can provide each element individually. This is recommended if a soil test indicates the need to significantly adjust one of the components. Potassium (K) levels can be boosted with greensand or potash. Phosphorus (P) can be added by using bonemeal or rock phosphate. Animal manure, blood meal, and urea provide nitrogen (N). There are many other choices for organic approaches to fertilizing, such as using fish emulsion and seaweed preparations.

All soil can be improved by adding compost. In fact, any kind of organic matter that absorbs and holds water, or provides air spaces, will change things for the better. The options are numerous: composted animal manure (cow, horse, chicken, or rabbit), composted leaves, grass clippings, and homemade compost from kitchen scraps. The general guideline for soil is that it must drain well but hold water long enough for the plant to utilize. Whether the soil is too heavy or too sandy, adding organic matter in the form of compost will help. It’s recommended that fresh manure not be used, as it could burn the roots and harm the plants, though there are different schools of thought on this. When in doubt, compost the manure for a period of time prior to use.

If you don’t have your own compost, the local hardware stores will have plenty of good bagged options, including various composts, manures, peat moss, and the so-called soilless mixes, which contain essentially the same materials as seed-starting media. Be aware that peat moss used in large quantity increases soil acidity. Often, an excessively acid soil will show itself when the tomatoes set fruit that start to enlarge and then show signs of blossom-end rot (BER).

Many tomato growers have their own ways of improving the tomato planting hole. Adding, from bottom to top, composted leaves, manure and straw, cottonseed meal, bonemeal, lime (as a preventive against BER if the soil is on the acid side), and sand, and topping with soil, would give the plant everything it needs to grow well.

Tomato plants that are planted in cold soil and under the threat of continued cold weather, even frost, will not progress quickly at all and will be equaled by plants set in much later, once warmer weather arrives. If you must get your plants in early, because of either your particular availability and schedule or the desire to grow early tomatoes, you can use products or methods to protect the plant and provide some needed warmth. Season extenders include water cloches (such as the Wall-o-Water) and hot caps, as well as temporary physical barriers for larger garden areas, such as tunnels built of PVC hoops and covered with materials such as plastic or row cover. If you do plant out your tomatoes early and frost is forecast, you must provide protection. If you cover the plants with pots, be sure the foliage doesn’t touch the sides. Row cover, loosely draped over the plants, offers a few degrees of protection, and several layers can be used. Plastic covering is not a good idea as it transfers the cold temperatures to any foliage that it comes in contact with and causes visible damage. To provide the most warmth possible for early transplants (especially in regions with a short growing season), try “trench planting” — near-horizontal planting at a shallow depth, with just a few inches of top growth exposed.

Cutworms are annoying springtime pests that can encircle and cut through the tender stem at the soil line, severing the plant from the root system. Easily ward off cutworm damage by fashioning a loose-fitting collar (use paper or aluminum foil) around the plant base, with some of the collar lying below, and some above, the soil line.

Once a seedling is planted and the cutworm collar (if using) is in place, the next step should be mulching. Mulch options include untreated grass clippings, shredded hardwood leaves, newspaper, or any other layerable, water-permeable barrier that will keep the soil off the foliage. Many a tomato plant has become infected very early in the season by having microbe-filled soil splashed onto the lower foliage; mulching is the key way to avoid this. You can also use landscape fabric or plastic mulch. Research has shown that mulching with red plastic can significantly increase yield and speed up fruit maturation.

One of the best mulches for tomato plants is chemical-free grass clippings. As they break down, they add nutrients to the soil; they also keep weeds from sprouting and prevent soil from splashing up onto the lower tomato leaves.

The final step after planting is a deep watering at the base of the plant. It’s a good idea to plant your seedlings in the late afternoon so that they have the nighttime to adjust a bit before being exposed to the full sun. If your tomato transplants are from individual pots with well-developed root systems, adjustment will be very easy. If you’re separating tomato plants from a mass of seedlings, you’ll have to watch them carefully for a week or so after planting, watering often to ensure that the plants’ roots have reestablished adequately.

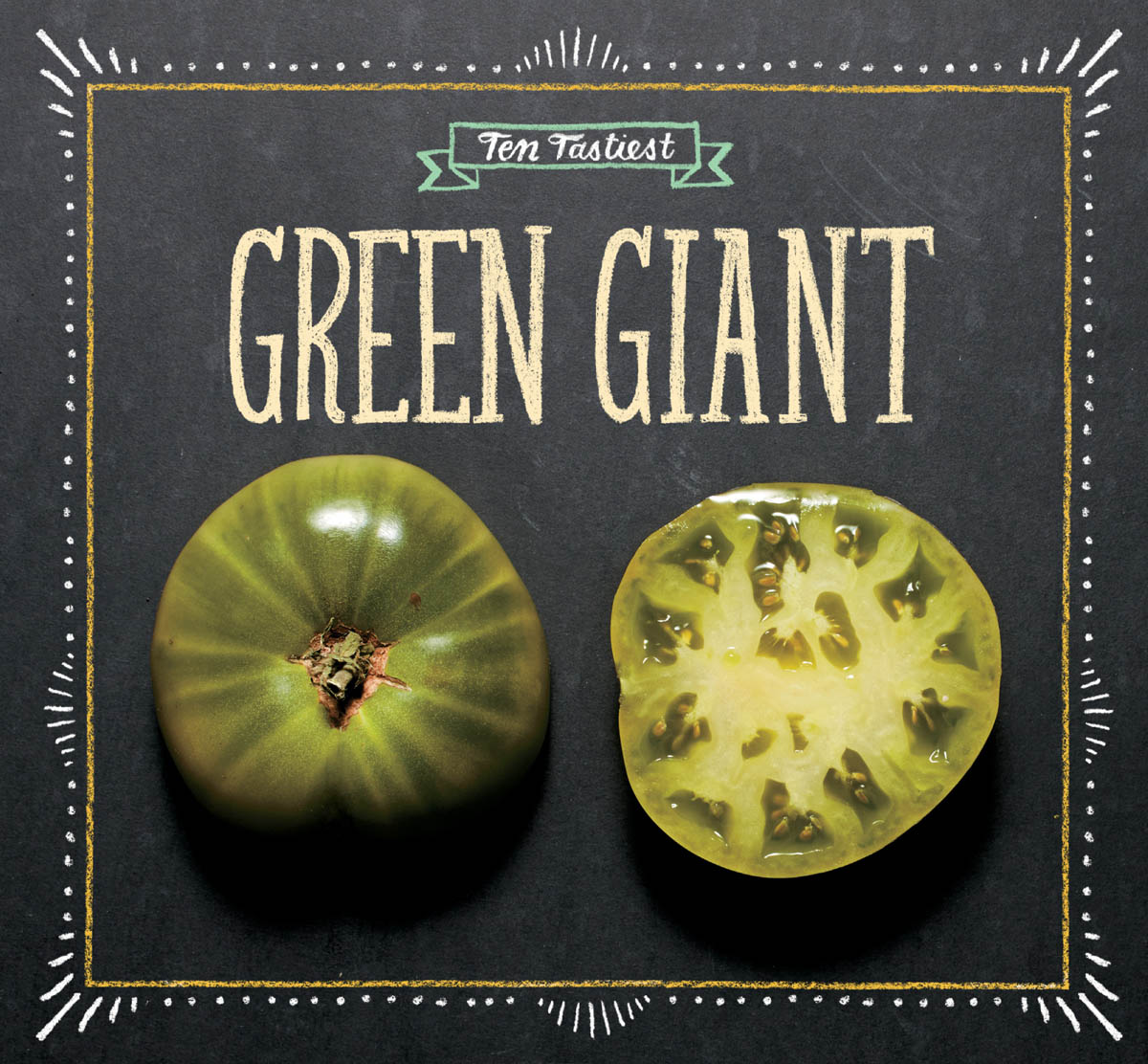

The flavor of Green Giant took me by complete surprise at first bite. The texture, similar to Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom and Brandywine, presents plenty of succulent flesh surrounding the many small seed cavities. The intensity of flavor nearly overwhelms, and it is perhaps most similar to Sun Gold in approaching perfection. As a class, large-fruited tomatoes that retain green flesh when ripe are uniformly delicious, but Green Giant edges out even Cherokee Green in its excellence.

Raised beds are a way to build up the soil in an in-ground garden in order to avoid poorly draining or otherwise poor-quality soil. You may choose to build up the soil only in certain spots. In this way, a garden can have areas of elevation where needed, and the materials used to create the raised area, such as bagged or bulk topsoil and/or compost, can be of a higher quality or different material than those that make up the rest of the garden. Or you can build raised beds for the entirety of your garden.

You can raise the beds for your tomatoes with or without a confining structure. In the past, I’ve created raised rows using bags of soilless mix and planted the tomato plants deeply into the mix; excess water then drains from the raised bed area. Because my soil drained poorly, if I hadn’t done this, my tomato plants would have sat with wet feet for prolonged periods after a rain, potentially drowning the plants.

A more typical raised bed garden is made up of well-built sets of squares or rectangles, typically from wood or concrete blocks, with wide aisles of gravel path or lawn that allow for complete access to all sides of the garden. These raised beds can be more work to create and more expensive to fill, but they are also well contained, neat, and more controllable. It’s important not to crowd your plants as you plant in raised beds — as they mature, they could tangle into quite a jungle.

Because of the geography of your yard, you may find that there’s no place to site a garden where it will receive enough sunlight to grow tomatoes. Fortunately, it’s possible to have great success by bringing the plants to the sun — whether that’s on a deck, patio, or driveway — simply by growing in containers. Even if you have enough sun, you might want to use containers if you have a buildup of disease in your soil or poor drainage. And growing in containers does not mean your options for tomato varieties will be more limited. Given sufficient container size and an appropriate plant support system, even indeterminate, large-fruited tomatoes can excel when grown in containers. My own experiences over the past decade (in which I’ve grown more and more of my tomatoes in containers) taught me that tomatoes grown in containers can equal those grown in the ground, in every way imaginable.

Using creative staking and container gardening allows anyone with good sun exposure to have a productive garden. Every year my driveway becomes my main area for growing tomatoes, along with peppers and eggplant.

Anything that holds soil and drains through the bottom works fine for a planting container. I’ve used plastic pots in varying colors; the large pots that nurseries use for shrubs or trees are perfect. Grow bags, made of fabric or plastic, come in varying sizes and work wonderfully. They are durable, can be reused many times, and can withstand annual bleaching without loss of structural integrity; some even have handles for easier transport. Clay pots are generally fine but could be problematic in very warm areas, as the porous material is prone to greater moisture loss from evaporation.

I’ve found that large-fruited indeterminate tomatoes require containers with a volume of at least 10 gallons to perform as well as they would in a typical in-ground garden. Dwarf and determinate tomato varieties will do just fine in 5-gallon containers. Recently, I’ve been experimenting with ways to get enough fruit from indeterminate plants for evaluation and seed saving using 2-gallon containers; this requires some specific pruning and staking techniques and close monitoring to ensure adequate nutrition and moisture.

For my own containers, I combine one 2.5-cubic-foot bag of commercial soilless mix with one 25-pound bag of composted manure. An alternative that may be more cost-effective is to create your own soilless mix by combining sphagnum peat moss and composted softwood bark (in a 3:2 ratio), adding some perlite, perhaps a bit of a wetting agent and a trace of slow-release fertilizer, if desired, and composted manure. Screened compost can also be used. Avoid using garden soil to fill containers — it won’t drain well in a container, and also carries the risk of introducing soilborne diseases.

Keep in mind the two major challenges with container growing: providing sufficient water and preventing the container from toppling over once the plants have grown large and become laden with fruit. Setting up drip irrigation solves the watering problem but has its own issues, such as cost, effort to erect, and suitability for the location of the garden (for example, since my container garden is our driveway, setting up a large drip system in a location that is necessarily temporary is more work than I’d like to undertake). Though it takes daily monitoring, hand-watering containers offers frequent opportunities to monitor progress, identify developing issues, and ensure ripe fruit is harvested when it’s ready. Self-watering containers are a good, effective option but are more costly, and the impact of this expense grows with the size of your garden. Methods that I employ to keep container-grown tomato plants upright are described in Staking Containers.

Congratulations! You’ve done a lot of hard work to get to this point. You’ve done lots of digging, testing, mixing, and lugging, and it will all pay off in a few months when the harvests begin. With the tomatoes planted, cutworm collars in place, and plants mulched and watered, it’s time to consider the ways to physically support them.

Securing a stake close to the base of the seedling helps to ensure that the plant won’t bend at the bottom once its top becomes heavy with fruit. Since tomato plants grow quickly, tying them to the stakes is often a weekly activity.

The vast majority of tomato varieties benefit from being staked. For indeterminate tomatoes, the taller the stake, the better; such varieties will easily reach 8 feet or more by the end of a growing season. Dwarf and determinate tomatoes, which can grow up to 4 feet, require a stake of equal height to keep them from sprawling.

Good tomato stakes can be made of any strong material — most are wood, plastic-coated metal, or bamboo. Whatever material you choose, a stake must be durable enough to withstand being hammered as deep into the soil as possible. It must also stay upright when burdened with a fully fruiting, tall plant experiencing the gusts of a summer thunderstorm.

A local gardening friend recently shared with me his fondness for growing tomatoes in straw bales — basically, a different version of container gardening. There are many different ways to go about the process, including variations on when and how to wet the bales and what kind of fertilizers to use for pre-treating the bales. Here are a few of the basics:

Tomatoes are referred to as vining plants, but they don’t climb by automatically attaching themselves as they grow, as ivy or morning glories do. They need to be continually secured to the vertical support using ties made of relatively soft material, such as sisal twine. Make the initial tie of the vine to the stake at 6 inches above the soil. Rather than tightly binding it to the post, tie it loosely to allow for growth through the season. I use the twine to tie the plant to the main stake every 6 to 12 inches, depending on the behavior of the individual plant. Some grow more rapidly and rampantly than others, and some varieties seem especially floppy and weak (particularly many of the paste or heart-shaped tomatoes). I often use multiple stakes for a single variety if I choose to prune it minimally or not at all. Sun Gold is such a rampantly growing, heavily yielding type, and is so popular in our family, that it receives the multiple-stake treatment every year.

Closely securing the main growing stem to the stake prevents the naturally weak tomato plant from flopping over. If the tying job is ignored for too long, vines can easily snap with the weight of developing tomatoes.

If you grow tomatoes in containers, providing adequate support becomes a matter of location. Of course, you can provide a stake of suitable height in the container itself, and it will be effective as long as the plant is young and not yet heavily laden with foliage, branches, and developing tomatoes. Once it grows in, however, it will need additional support.

Appropriate placement is an easy solution to the issue. If you position the tomato containers at a driveway or patio’s edge where it meets the lawn, you can pound stakes of appropriate lengths into the ground and push the pots up against the stakes, providing all of the support needed for vertical growth. With this approach, I find it helpful to settle the transplant near the edge of the pot, which minimizes breakage near the bottom of the plant as it is stretched to meet the stake. If you have plants growing in larger pots (10-gallon minimum), you can use the large containers to anchor plants in adjacent smaller containers. In my driveway garden, I have 10- or 15-gallon pots containing indeterminate tomatoes all along the perimeter. In front of each of those pots I place a 5-gallon pot or grow bag with a dwarf tomato variety, placing the stake for supporting the dwarf into the larger pot. This prevents the dwarf plant from toppling over once it becomes mature and laden with fruit.

If your containers are on a deck and the pots are pushed up against a railing with vertical slats, try lashing a taller stake to a slat. This provides a perfect way to grow your tomatoes vertically and avoid tipping the pot.

Nothing is easier than planting a tomato and letting it roam free. Tomatoes grown this way are not pruned, and potential yields are enormous. With this method, it’s important to consider all of the potential issues that would negate the advantages of ease and higher yield:

Growing tomatoes in cages is a way to maximize yield (because they are typically not pruned) and minimize effort (once the cage is in place). Most often, tomato cages are fashioned from concrete reinforcing wire, manipulated to form a ring of varying height and diameter most appropriate for the garden size. Tomato cages are generally 4 to 5 feet tall and 3 feet in diameter and must be secured at two points by posts of similar height to prevent the plant from toppling over at maturity. The wide openings in concrete reinforcing wire make it easy to reach in and pick the ripe tomatoes.

Training tomatoes vertically with stakes and cages allows for closer planting. Mulching with shredded leaves and grass clippings around the plant and between rows helps prevent soil from splashing onto the lower foliage, thus minimizing the spread of soilborne diseases.

For this technique, the tomato seedlings should be spaced so that a foot or more of space remains between the cages. To plant, set the seedling into the ground and then center the cage over the seedling (it is helpful to provide a single stake of the height of the tomato cage to ensure initial upright growth). Secure the placed cage at two opposite sides by stakes or posts, and tie the tomato to the center stake as it grows. The plant, which is most typically grown unpruned, will quickly fill the cage, and if the soil is rich and full of nutrients, the potential yields of caged tomatoes are enormous. The main concerns with caging tomatoes are cost of the cages, work needed to set up the cages, and finding an adequately large area to store the cages during the off-season.

Big-box hardware stores typically sell tomato cages that are less than 5 feet tall and look like a narrowing cone, with prongs at the bottom and three rings of decreasing diameter attached to the outer prongs. Many other variations on tomato cages exist as well, including collapsible examples that end up as squares. These smaller-scale cages are quite inexpensive, but of limited and specific use. Those who plan to grow indeterminate tomato varieties (most large-fruited, colorful heirlooms fit this category) will be disappointed in such tomato cages, as the plants will quickly outgrow them. However, they are perfect for determinate and dwarf varieties, which grow to 4 feet tall or less. The short, cone-shaped tomato cages are also well suited for peppers, eggplants, and tall flowers.

Most tomato varieties are indeterminate, meaning infinitely growing (until killed by frost or disease). They are often referred to as “vining,” but unlike most vines, they don’t wind or adhere themselves to adjacent structures; they must be supported and secured. Since vertical support removes most of the plant and all of the tomatoes from contact with the soil, it minimizes a mode of disease entry into the plant (as long as the area around the plant is well mulched).

Once the decision has been made to stake the tomatoes, you will find that variations on staking tomatoes are infinite. It really comes down to the creativity and imagination of the gardener, available space, and budget.

If a garden is large and will be maintained in one location for many years, a good way to avoid the cost and labor of pounding in many stakes is to grow tomatoes up a strong line or chain, suspended from above. This method requires the placement of very strong, tall posts at each end of a row of the garden, perhaps even cementing them into place. A chain is suspended between the two posts at the top, and at intervals where the tomatoes will be planted, strong twine droplines are tied to the overhead line and suspended down to the ground. Once the tomatoes start to grow, they are tied to the dropline in the same way as if it were a stake. If the gardener is very vigilant, the tips of the vines can be wound around the twine as they grow upward; however, the rapid growth of many plants will invariably lead to the need to do some remedial tying. This method does not allow for easy crop rotation, so disease buildup in the soil could be an issue that becomes more serious each year.

The overhead piping in this structure (created by my local tomato-growing friend Richard Baldwin) ensures good vertical growth. Heavy string is suspended from the pipes into the containers below, and the tomato vines are secured to the string as they grow.

Another option is to create teepees from three or four tall, slender poles, spaced at the bottom but meeting and joining at the top. A tomato seedling is planted at the base of each teepee pole and secured to the pole as it grows upward and outward.

Tomatoes grown this way often have several advantages. Compared to tomatoes grown in a single row, they have less of a chance to develop sunscald, simply because some of the fruit will be in the center of the structure as they form and mature. The structure itself is more stable than vertically staked plants in rows, and less likely to topple in the wind. It also creates a unique visual focus in the garden that could be quite dramatic.

The Florida weave technique, also known as the cat’s cradle, is an effective, easy, and relatively inexpensive way to support indeterminate varieties of tomatoes grown in rows. The key is to provide robust support (able to withstand heavy plants and the winds that come with summer thunderstorms) at the end of each row.

Mark out your tomato rows, spacing a minimum of 3 feet between rows. At the ends of each row, hammer sturdy poles, such as steel T-posts used for fencing (preferably at least 6 feet tall), deeply into the soil. Plant the tomato seedlings down the row, using an optimal spacing of 3 feet between plants if possible, and hammer additional poles into the row after every two plants. Secure sisal twine to one of the end poles at about 10 inches above the soil line, and run the line along one side of all the plants, looping it around the internal poles. At the end of the row, loop the twine around the other end pole and bring it back down the row so that the twine provides support for the plants on the other side, again looping back around the internal poles and then securing it to the original point.

Repeat this process as the plants grow (every 10 to 12 inches). Plants grown this way may benefit from a moderate level of sucker removal in order to prevent sucker growth from cascading downward and creating an impenetrable tangle.

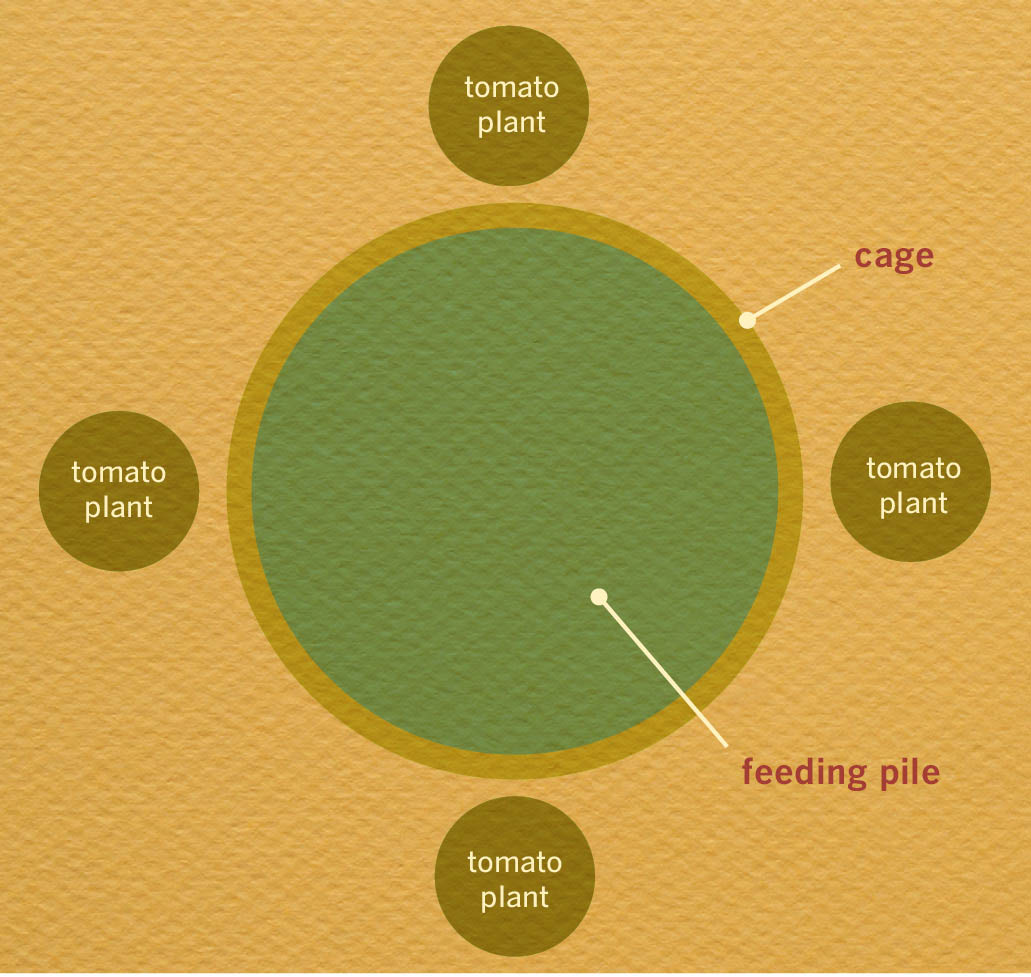

One interesting variation on caging is called the Japanese ring. The technique calls for tomato seedlings to be planted around the outside of a wire cage that is filled with nutrient-rich organic material. This serves as the “feeder pile” — a reservoir of nutrients and moisture into which the roots of the tomato plants will grow.

To create a Japanese ring, bend a 91⁄2-foot length of 6-foot-tall concrete reinforcing wire into a circle and support it with four metal garden stakes driven into the soil. Into the center of the cage, heap a 2-foot layer of rich planting medium (such as a mixture of compost and fertile topsoil). Create a depression in the center of the pile to enhance water retention.

Spread a thick layer of the planting medium around the outside of the cage, and plant tomatoes equidistantly around it (4 plants per cage). Water the pile as needed, and add a balanced fertilizer or fresh application of compost every 2 or 3 weeks, if necessary. Tie the plants to the cage as they grow. The plants will eventually grow up the cage and into the center, and they will load up heavily with fruit.

The first time most people pop a Sun Gold cherry tomato into their mouth and crunch down, the look on their faces is priceless. Sun Gold is unique in the range of flavors that it exhibits. Picked pale orange, there is fullness and complexity with a nice snappy bite. At medium orange, sweetness and tartness play out in a delicious dance of intensity. At maximum ripeness, they are like candy — nearly overwhelmingly sweet. In my experience, nothing in the tomato world tastes like Sun Gold. Because of this, it is the only hybrid that finds a place in my garden every year; no open-pollinated alternative exists.

Aside from questions on my favorite tomato varieties, I am most often asked about pruning and suckering of tomato plants. Suckers, or side shoots, are additional fruiting stems that emerge all along the plant at the junction of the main stem and leaf stems. If the leaf stem emerges from the main stem at an approximate 90-degree angle, the sucker will be at a 45-degree angle. The reason that indeterminate tomato plants grow out of control so quickly is that the suckers themselves go on to produce suckers, and a plant can become densely complex by midseason.

An indeterminate tomato plant extends its main growing stem indefinitely and generates suckers at each point of a leaf stem attachment. Essentially, suckers are the tomato plant’s way of passing on its genetic heritage by providing a fail-safe mechanism for producing as many seeds as possible; the more branching, the more flowers, which lead to more tomatoes, which lead to more seeds, which to a plant means future survival. Contrary to pervasive urban legends, they do not sap energy from the main tomato plant, and allowing them to develop does not delay fruiting or ripening of any tomatoes from the main stem. Removal of suckers has implications for eventual yields and for how the plant needs to be maintained, so a detailed discussion on retention or removal of suckers is an important one to have.

Suckers, or side shoots, develop at every node between the stem and leaves up the vines of indeterminate tomato varieties. Some gardeners remove them, but leaving them in place will not negatively affect the plant.

Each sucker allowed to grow provides additional flower clusters, and hence there are additional chances for fruit set. Here’s an example to illustrate this point. Picture a tomato plant that has all of its suckers removed, tied to an 8-foot stake. A blossom cluster is produced at 8- to 12-inch intervals, starting at 2 feet from the soil line. During the season, the majority of the flower clusters open at times when the temperature and/or humidity is not suitable for pollination, leading to blossom drop. As a result, only a handful of fruit is produced on the 8-foot-tall plant, with no mechanism available for producing additional flowers. If just one sucker would have been maintained, the number of flower clusters would have doubled, and it is highly likely that flowers on that additional growing shoot would have opened under more suitable conditions, thus significantly increasing the yield of the plant. Following this logic, each sucker or side shoot that’s allowed to develop will significantly increase the yield potential of the plant (given a long-enough season).

Suckers that are allowed to grow also provide additional foliage cover. In climates where the searing sun beats down on the exposed developing tomatoes, sunscald is a definite risk (see Fruit Damage). Since direct sun is not needed to promote ripening, it is far more preferable to have the fruiting cluster shaded by foliage.

An indeterminate tomato plant can grow out of control in a hurry due to the formation of suckers, and then suckers from those suckers. Disciplined removal of suckers in order to provide a plant with a finite number of fruiting stems or branches leads to more control over growth and a far easier support task. In a plot with a very crowded layout, pruning to one or two stems will allow for more air circulation between plants and a way to maintain order in what could otherwise become a tangled mass of vines.

An easy way for gardeners in warm climates to extend the harvest is to stagger the planting of the tomato seedlings. This can be done by starting a second round of seeds; the easier solution, however, is to simply root some of the suckers that the tomato plants are already producing so enthusiastically. Suckers root very quickly and easily, producing a clone of the plant they came from. Similarly, you can root the section removed when you top a plant, or even a young plant taken down by a cutworm (if you get to it before it wilts in the sun).

To do this, cut a 6-inch-long sucker from one of your healthy plants and put it in a glass of water, or push it gently into a pot of well-moistened potting mix. Some gardeners find that suckers will root directly in the garden if placed in a shaded area. It is important to keep the rooting suckers out of direct sun. Typically, a sucker will root and begin to show renewed growth in a few weeks at most. Often, the sucker in the moist soil will wilt just a bit until new roots begin to grow.

For a sucker rooting in a glass of water: once it has a nice set of new roots, pot it up in fresh potting mix and allow it to adjust in a shaded location for a few weeks before setting it into its final location.

In addition to snipping suckers, skillful “topping” of fruiting tomato branches and stems at particular heights is another way of maintaining control over a plant. Since more flowers form than will pollinate and ripen before the end of the season, topping also ensures that a plant doesn’t put energy into developing tomatoes that would never get a chance to properly ripen. To do so: pick a plant height equal to the length of the supporting stake, and, with clean shears or fingers, pinch the stem just above a leaf stem that sits close to the final flower cluster from which you desire fruit set. Topping is an excellent way to prevent plants from becoming so top heavy that they topple in storms or develop kinks in branches, which can lead to disease and death of the plant above the kink.

Determinate tomato varieties are unusual in that they grow to a genetically predetermined height and width and then produce flowers at the end of the flowering branches, thus limiting outward growth. In a sense, they are self-pruning, and any removal of suckers will reduce the eventual yield of the plant.

Dwarf varieties, though they grow and behave like very slowly vertically stretching indeterminate types, don’t require pruning to prevent uncontrolled growth and sprawl. A few suckers can be removed in order to open up the center of the plant — the foliage of dwarf tomatoes often grows densely, and removing some of it will encourage good air circulation, which is especially helpful in hot, humid gardens where foliar diseases thrive. Keep in mind, though, that pruning suckers from dwarf tomatoes will reduce yields.

Adequate, even watering is essential for healthy plants. Tomatoes grown in soil, in a traditional garden bed, often receive sufficient rain throughout the growing season to render the need for deep watering infrequent, especially when the soil contains a lot of clay. Well-mulched plants may show some wilting during the hottest part of the day, but in the evening evapotranspiration decreases and the plants bounce right back. This, combined with the ever-deepening water-seeking roots, remedy the temporary water shortage. If it is dry, a weekly deep watering will suffice; a good workaround is the use of drip irrigation, which provides a constant water source for the plants.

Container-grown plants require much more frequent watering because they have less soil and less available water per root area for each plant. When the seedlings are very young, weekly watering works well, but once growth takes off, in the absence of substantial rain, daily watering (each morning) will be necessary. Fully grown plants during a heat spell should receive morning and late afternoon watering. My method is simple: with no nozzle and hose running full, 5-gallon pots receive a count to three, and 10-gallon pots a count to five, resulting in a bit of excess water eventually draining out of the bottom of the pot.

The mantra of proper watering is: water from the bottom, and never wet the foliage. When you think about it, this can be controlled only part of the time; clearly a heavy rainstorm comes in from above and saturates the tomato foliage. Proliferation of foliar diseases is always a follow-on possibility, particularly if disease agents are already present, the plants have a prolonged period of wet leaves, and it is followed by high heat and humidity. Nevertheless, by being mindful and watering the soil instead of the foliage, you can at least reduce your role in the proliferation of foliar diseases.

One of the most important things you can do before you go away for vacation is to make sure someone whom you trust, and who understands your garden’s needs, is on hand to provide the necessary watering regimen while you are gone.

Water at the base of the plant to keep the upper foliage as dry as possible; use a thick mulch to keep the planting medium from splashing onto the lower foliage.

Rich garden soil that has adequate nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (information that can be gained by doing a soil test) will grow great tomatoes. The ideal ratio of these three key nutrients is 1:4:2 (highest in phosphorus). Too much nitrogen promotes foliar growth at the expense of fruit set. There are specific fertilizers for tomatoes; however, use of any fertilizer should be based on need (what the early soil test tells you, what your past experience has been, and plant performance during the season). If you produce your own compost, working it into the soil around your plants a few times each season may be all that you need. Use of fertilizers tends to be inexact, since there are so many variables associated with your own particular location.

Where you’re growing your plants — in the garden or in a container — will determine how often you need to fertilize. Nutrients are retained longer near the root zone of garden-grown plants. The frequent watering of containers means that nutrients wash out the bottom more quickly, which calls for more frequent fertilizing. No matter how they’re grown, the foliage color is a good indication of the need for a boost; the rich, dark green starts to fade to a paler hue if a plant needs some nutritional attention.

Once the plants are up and growing vigorously, the fertilizing philosophy of the individual gardener comes into play, especially when deciding between chemical (such as Miracle-Gro or Vigoro brand products) or organic (such as Tomato-tone or fish emulsion) methods. With so many options of products and materials for both approaches, it is well worth the time for all tomato growers to do their own research, including trial and error, though my approach can be used as a starting point.

I’ve tried both chemical and organic fertilization approaches with good results throughout my gardening years, but I’ve settled most recently on using a high-quality, slow-release, balanced fertilizer for vegetables, such as Osmocote or Vigoro tomato food, applied every few weeks, because it fits my current emphasis on container gardening. I increase the frequency of feeding to weekly once my container-grown plants put on a heavy set of developing tomatoes.

Keep in mind that a bit of wilting isn’t a problem. Wilted plants recover in a hurry, and even well-watered plants will show some foliage wilting when the sun is overhead and the temperatures hover in the 90s or higher; this is the plants’ way of conserving moisture. Real vigilance for severe wilting during hot spells is needed if the plants carry heavy sets of green fruit; the uneven watering experienced by a plant that dries to wilting, followed by a gush of water, often leads to blossom end rot. Mulching helps to retain moisture. Drip irrigation is a great solution, and using planting mix that has water-retentive crystals, though costly, will provide help as well.

I love genealogy and am quite nostalgic; that trait has applications in the pursuit of old tomato varieties, as we try to find out what our grandparents, or their parents, may have grown in their gardens. The best tool for this type of sleuthing is old seed catalogs. The catalogs provide the names of vegetables in American gardens as far back as the mid-1800s.

With information from old catalogs in hand, it comes down to knowing where to look for the varieties, if indeed they still exist. Sadly, many are now extinct, though it is surprising how many of the old types are still available to be grown in our gardens. One useful resource that I started using in the early 1990s is the Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN), a portal that allows a search of the plant materials in the National Genetic Resources Program (NGRP), within the research service of the USDA. With the names of many old tomatoes in hand, I was delighted to find that many varieties thought to be long gone resided in the NGRP, and I requested and received samples from dozens and dozens of treasured old tomato varieties.

Occasionally, I order a tomato just because of its fanciful name. One such variety, Ferris Wheel, made its way into the NGRP collection in 1943 according to the information provided on GRIN. I was in no rush to grow it until I was looking through an old catalog from the Salzer Seed Company and I noticed that Ferris Wheel was one of their tomatoes, with a release date between 1894 and 1898. The Salzer description was quite over the top in superlatives.

After realizing that Ferris Wheel was an authentically very old variety that likely hadn’t been grown for many years, I gave it a try, in a 15-gallon pot in my driveway in 2001. The plant had the characteristic somewhat-wispy foliage and open habit of many of the large pink beefsteak types. The fruit were in the size range of 1 pound or more, were pink with pronounced green shoulders, and had some ribbing and irregular shapes. The flavor was just remarkable — full and sweet, complex and delicious. Ferris Wheel became an instant favorite, and I grow it often. My guess is that it is quite similar to an old variety released by the Henderson Seed Company in 1891 called Ponderosa. In fact, Ferris Wheel could indeed be a “selection” that the Salzer company made from Ponderosa, perhaps from a plant showing a distinct improvement in a particular characteristic. It certainly is a winner, and one can only wonder why it disappeared from gardening awareness for so long.

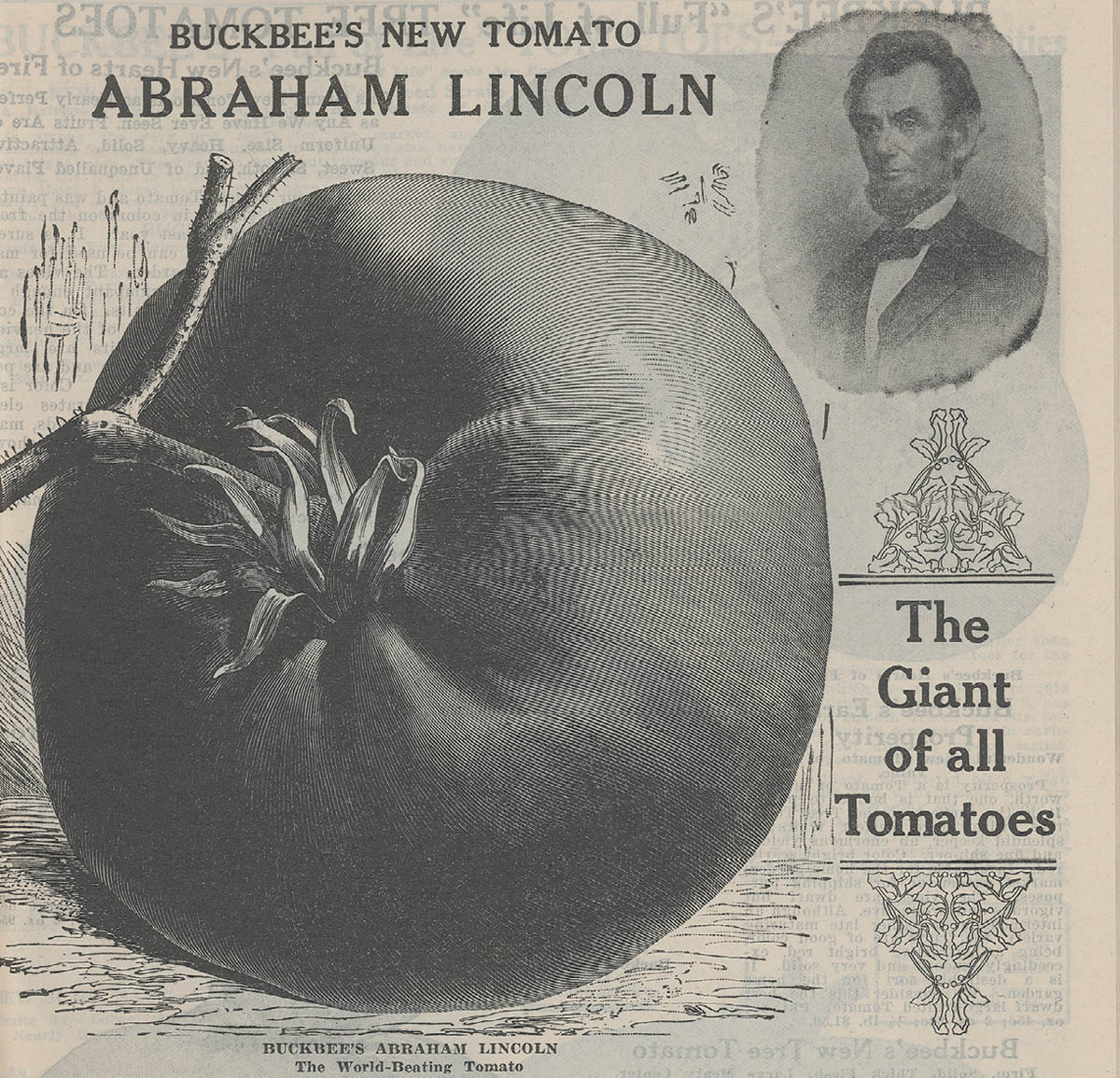

Surrounding this historic variety are a few delicious mysteries. The first time I heard of it was while reading The Total Tomato by Fred DuBose. Mr. DuBose had a very helpful listing of recommended tomatoes ranked by stars (from one to three), and Abraham Lincoln was among his very few three-star tomatoes. Though it is open pollinated (non-hybrid), it is considered a commercial, rather than family, heirloom. It was the cover tomato — the feature release — of the Buckbee Seed Company catalog in 1923. In that catalog, Abraham Lincoln is described as being very large, nearly round, red, extremely productive, and delicious. The variety was sometimes described (particularly in the entry in Mr. DuBose’s book) as having unique dark-toned, bronze-colored foliage that stood out in a garden.

For a variety that is reasonably recent and has been continually available for gardeners to grow through seed catalogs, obtaining seed that delivers what the old catalogs describe continues to be quite a challenge. When I grew out Abraham Lincoln tomato seed from the Shumway Seed Company back in 1987, the plants were green, semi-determinate, and less than 5 feet tall, and they produced tomatoes that were only 3 or 4 ounces — not at all what was described in other references.

A few years later, I grew out seedlings from another supplier, and though it didn’t exhibit the unique bronze or purplish cast noted in the book entry, it was certainly indeterminate, and the fruit were large, closer to a pound. The flavor was quite delicious. Of course, there was no way to confirm if this was Abraham Lincoln as released by the Buckbee Company in 1923. It was, however, closer in description to the authentic variety than any I had grown to that point. And so I grow it still for its flavor, productivity, and history. It very well could have been a variety that my grandfather grew during his gardening years. And that possibility makes me quite happy to be growing it.

I include Big Boy here and in my garden purely as a testament to its historical importance. Though not strictly the first hybrid tomato, Big Boy was certainly the first wildly popular, revolutionary hybrid tomato. Released in 1949, it was part of Americana following the end of World War II that boosted morale and, in a way, defined the Victory Garden. Big Boy had an impact on tomato size, yield, future breeding efforts, and seed company focus going forward.

Prior to Big Boy, seed companies, the USDA, and university agricultural programs involved in breeding new tomato varieties worked toward releasing stable, open-pollinated types that could be replicated from saved seed. Big Boy changed all that. Creating hybrids is more labor intensive, so seed cost rose. Seeds couldn’t be saved, so customers had to return annually for seeds of hybrid varieties. Many of the new hybrids were also bred to resist disease. Big Boy also whetted the gardeners’ appetites for large, smooth, round, red tomatoes.

All of these factors pushed older, heirloom varieties, with their odd colors and irregularities, further into the background as the public rushed to grow the latest and greatest hybrids. Big Boy was followed by Better, Ultra, and various other designations of superiority, and Girls joined the Boys as well.

Belying its regal heritage, Lucky Cross is a flavor king among the large yellow-red bicolored tomatoes. As an offspring of Brandywine, Lucky Cross shows the same sort of big tomato flavor and perfect balance, rendering it unique among varieties in this color class, which typically have a very sweet flavor personality that borders on overly mild.