For various reasons, Rails has gained an undeserved reputation of being difficult to install. This chapter dispels this myth. The truth is that installing Rails is relatively easy and straightforward, provided you have all the right ingredients. The chapter begins with an overview of what you need to get Rails up and running and then provides step-by-step instructions for the installation. Finally, you’ll start your first Rails application.

An Overview of Rails Installation

The main ingredient you need for Rails is, of course, Ruby. Some systems, such as macOS, come with Ruby preinstalled, but it’s often outdated. To make sure you have the best experience with this book, it’s best if you start from a clean slate, so you’ll install it. After you have Ruby installed, you can install a package manager (a program designed to help you install and maintain software on your system) called RubyGems. You use that to install Rails.

That’s all it comes down to—installing Rails is a mere one-liner. The key is in having a working installation of Ruby and RubyGems. Before you get there, though, you need one other ingredient to use Rails: a database server.

As you’re well aware by now, Rails is specifically meant for building web applications. Well, it’s a rare web application that isn’t backed by a database. Rails is so sure you’re using a database for your application that it’s downright stubborn about working nicely without one. Although Rails works with nearly every database out there, in this chapter you use one called SQLite. SQLite is open source, easy to install, and incredibly easy to develop with. Perhaps that’s why it’s the default database for Rails.

Rails 6 introduces the use of webpack for processing CSS and JS files. This also means we’ll need to install Node.js to run JavaScript on the server and Yarn to manage our JavaScript dependencies.

- 1.

Install Ruby.

- 2.

Install Rails.

- 3.

Install SQLite.

- 4.

Install Node.js.

- 5.

Install Yarn.

Before you begin, note that the “many ways to skin a cat” adage applies to Rails installation. Just as the Rails stack runs on many platforms, there are as many ways to install it. This chapter describes what we feel is the easiest and most reliable way to install Rails for your platform. You go about the process differently for macOS, Linux, and Windows, but they all amount to the same thing.

No matter which platform you’re using, you need to get familiar with the command line. This likely isn’t a problem for the Linux crowd, but it’s possible that some macOS users and certainly many Windows users don’t have much experience with it. If you’re using macOS, you can find a terminal emulator in /Applications/Utilities/Terminal.app. If you’re on Windows, you can open a command prompt by clicking Start, typing cmd, and clicking “Command Prompt.” Note that you’ll use the command line extensively in your travels with Rails. A growing number of IDEs make developing applications with Rails even simpler, and they completely abstract the use of a command-line tool; but stick to the command line to make sure you grasp all the concepts behind many commands. If you later decide to use an IDE such as JetBrains’ RubyMine, you’ll have a great understanding of Rails and will understand even better where the IDE is speeding up your work.

Also, a quick note for macOS users: If you’re using a Mac and would prefer to use a package manager such as Fink or MacPorts, the Linux instructions will prove useful.

Go ahead and flip to the section that describes your platform (macOS, Windows, or Linux), and let’s begin.

Installing on macOS Catalina

You’d think that given the prevalence of macOS among Rails developers, installing Rails on macOS would be easy. And you’d be correct. First, we need to install Apple’s Developer Tools so that we can compile packages. Note that SQLite is preinstalled on macOS, so that’s one thing we don’t need to worry about.

Installing the Command Line Tools for Xcode

Follow the prompts to continue installation.

Installing Homebrew

Installing RVM

If your output isn’t exactly like this, don’t panic. Ruby is often updated with new security patches and features, but it should at least say Ruby 2.5.0 in order to support Rails 6.

Installing Rails

Again, if your output isn’t exactly like this, don’t panic. Quite likely a newer version of Rails 6.0 has been released. But to ensure compatibility with this book, please make sure your version number begins with 6.0.

Installing Node.js

Installing Yarn

Great! Ruby, Rails, SQLite, Node.js, and Yarn are installed and working correctly.

Installing on Windows

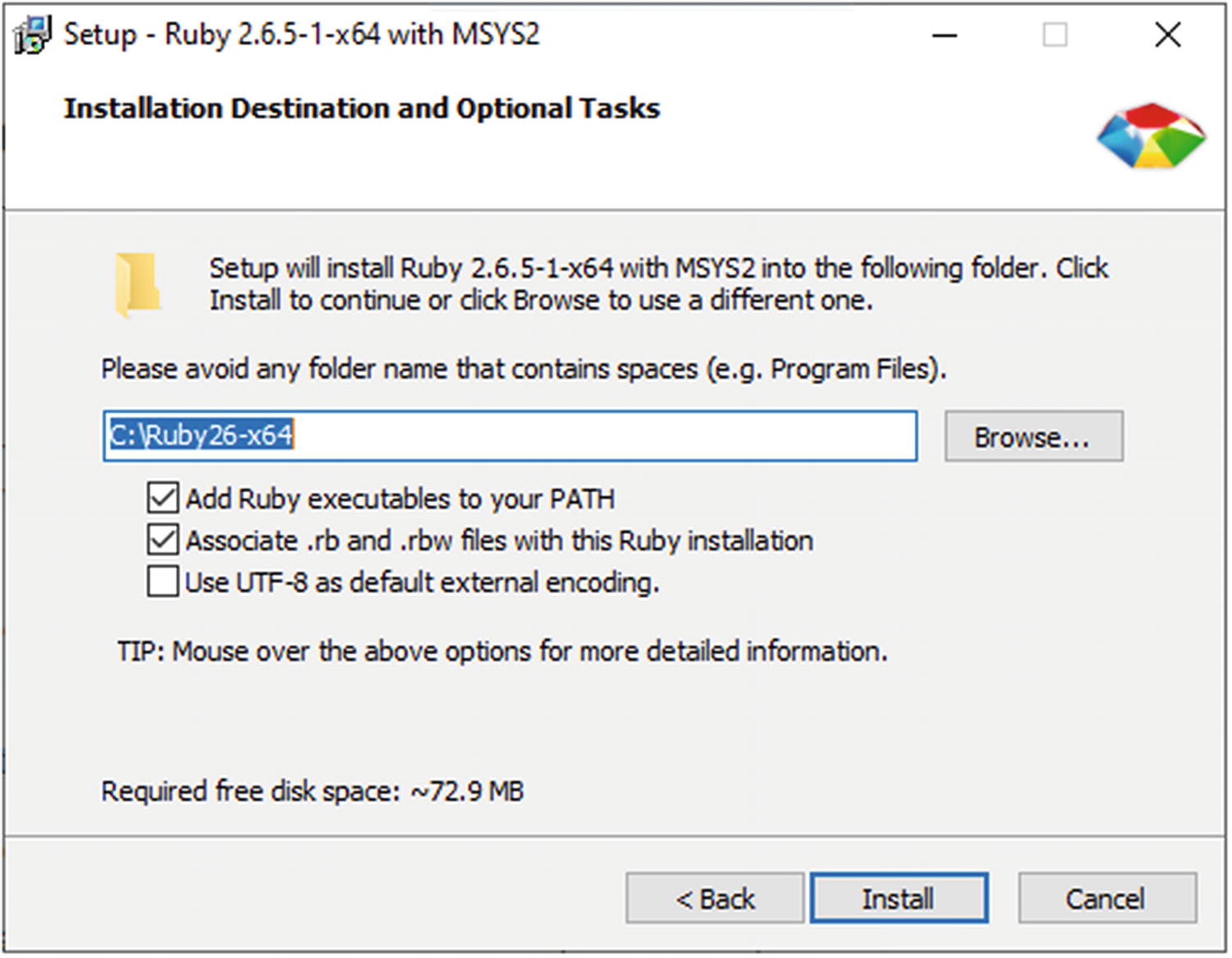

Installation on Windows is easy thanks to installer packages. You start by installing Ruby.

Installing Ruby

Installing Ruby on Windows is marvelously easy thanks largely to the one-click installer for Ruby. You can read more and download the installer from its website: http://rubyinstaller.org/.

The latest version of the installer at the time of this writing is Ruby 2.6.5-1. While a newer version of Ruby would probably still be compatible with Rails 6.0 and the code in this book, a safer bet would be to install the most recent stable Ruby 2.6 version.

Ruby installer for Windows

Installing Rails

You’ll be pleased to know that Ruby 2.6 comes bundled with RubyGems, a package management system for Ruby (http://rubygems.org), which makes installing Ruby libraries, utilities, and programs a breeze. This includes Rails installation.

The “-v ‘~> 6.0.2’” part of the command ensures that the most recent version of Rails 6.0 is installed—important for making sure you can follow along with this book. Be forewarned that the gem command can take some time. Don’t be discouraged if it seems to be sitting there doing nothing for a few minutes; it’s probably updating its index file. RubyGems searches for gems in its remote repository (https://rubygems.org), so you need to be connected to the Internet for this command to work.

That’s all there is to it! The one-click installer takes care of most of the work by installing and configuring Ruby; and because Rails is distributed as a RubyGem, installing it is a simple one-liner.

Installing SQLite

Installing Node.js

To install Node.js on Windows, simply visit https://nodejs.org/, and download the installer which is “recommended for most users.” (At the time of this writing, that’s version 12.13.1 LTS.) Run the installer, accepting most of the defaults, but be sure to check “Automatically install the necessary tools” to avoid more manual steps. Follow the remaining steps to complete installation of Node.js.

Installing Yarn

To install Yarn on Windows, simply visit https://yarnpkg.com/, click “Install Yarn,” and download the installer for the current stable version for Windows. (At the time of this writing, that’s version 1.19.2.) Run the installer, accepting the defaults, and complete the installation.

With Ruby, Rails, SQLite, Node.js, and Yarn happily installed, it’s time to take them for a test drive. Unless you feel like reading the installation instructions for Linux, you’re free to skip ahead to the “Creating Your First Rails Application” section.

Installing on Linux

Linux (and UNIX-based systems in general) comes in a variety of different flavors, but they share a lot in common. These instructions use a Debian-based variant called Ubuntu Linux, but they should apply to most UNIX systems with varying mileages.

Ubuntu Linux is a top-notch distribution that has rapidly gained mindshare in the Linux community. At the time of this writing, it’s one of the most popular Linux distributions for general use and is largely responsible for the increased viability of Linux as a desktop platform. It’s freely available from http://ubuntu.org and highly recommended.

Just about all Linux distributions (including Ubuntu) ship with a package manager. Whether you’re installing programs or code libraries, they usually have dependencies; a single program may depend on dozens of other programs in order to run properly, which can be a struggle to deal with yourself. A package manager takes care of these tasks for you, so you can focus on better things.

Ubuntu Linux includes the Debian package manager apt, which is what the examples in this book use. If you’re using a different distribution, you likely have a different package manager, but the steps should be reasonably similar.

The apt-get program keeps a cached index of all the programs and their versions in the repository for faster searching. Running the update command ensures that this list is up to date, so you get the most recent versions of the software you need.

Installing Ruby

If using Gnome Terminal, you’ll need to enable its “Run command as a login shell” option for RVM to work. Go to its Preferences ➤ Profile ➤ Command, and enable that option. Then close and reopen the terminal.

Installing Rails

With Ruby and Rails happily installed, you’re ready to move on to the next step: installing SQLite.

Installing SQLite

Installing Node.js

Installing Yarn

With Ruby, Rails, SQLite, Node.js, and Yarn happily installed, it’s time to take them for a test drive.

Creating Your First Rails Application

If you look closely at the output, you see that the subdirectories of app/ are named after the MVC pattern introduced in Chapter 1. You also see a name that was mentioned briefly in Chapter 1: helpers. Helpers help bridge the gap between controllers and views; Chapter 7 will explain more about them.

app/ | db/ | node_modules/ | README.md | yarn.lock |

|---|---|---|---|---|

babel.config.js | Gemfile | package.json | storage/ | |

bin/ | Gemfile.lock | postcss.config.js | test/ | |

config/ | lib/ | public/ | tmp/ | |

config.ru | log/ | Rakefile | vendor/ |

Starting the Built-In Web Server

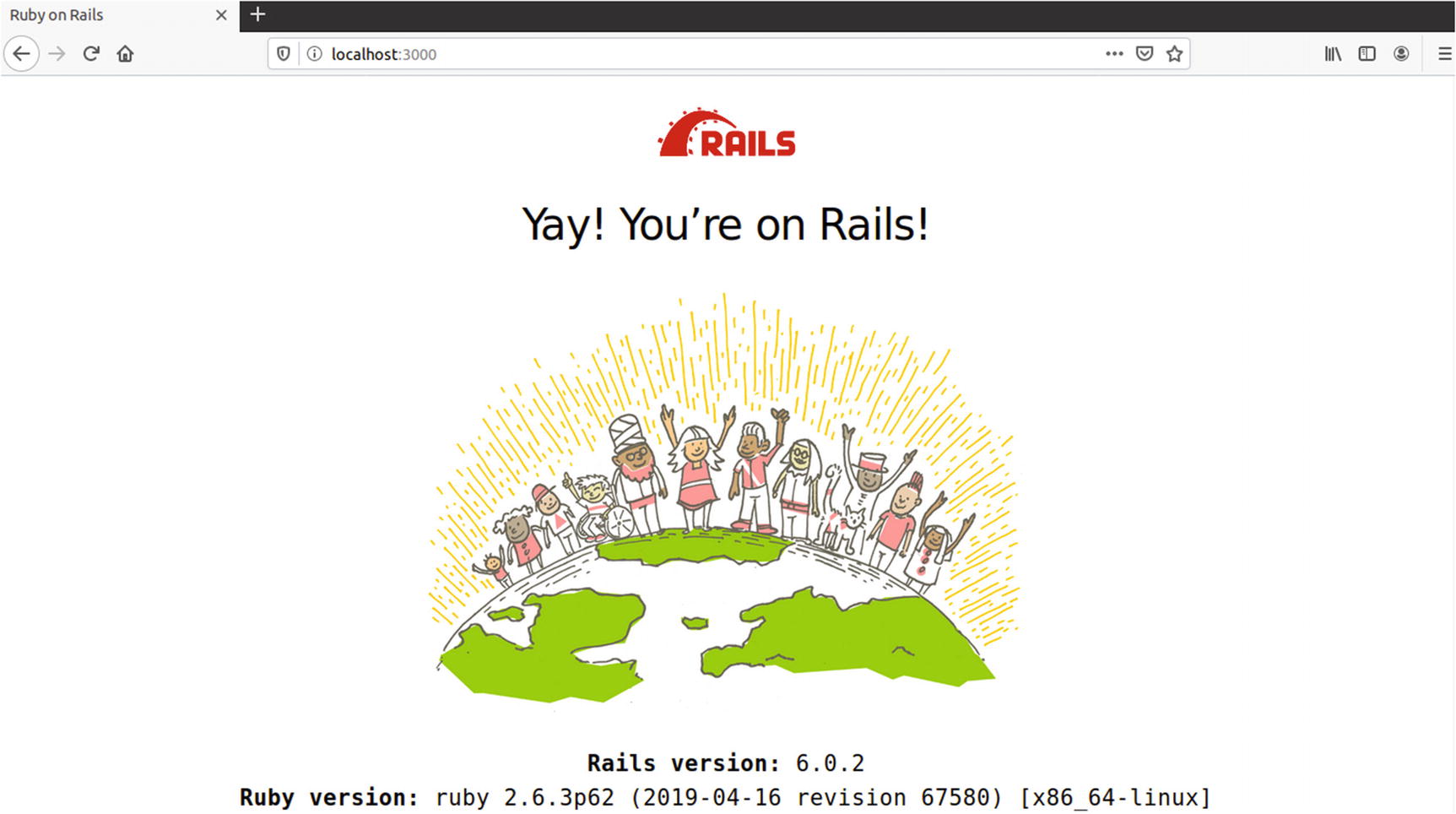

Next, let’s start up a local web server so you can test your new project in the browser. True, you haven’t written any code yet, but Rails has a nice welcome screen that you can use to test whether the project is set up correctly. It even gives you some information about your Ruby environment.

The message from the rails server command tells you that a web server is running at the IP address 127.0.0.1 on port 3000. That means that the server is running locally on your machine. The hostname localhost also resolves to your local machine and is thus interchangeable with the IP address. We prefer to use the hostname variant.

Rails welcome page

The welcome page is nice, but it doesn’t teach you much. The first step in learning how Rails works is to generate something dynamic. You’re about to learn why you called this project “hello”!

We’re sure it would be in violation of the law of programming books if we didn’t start with the ubiquitous “Hello World” example. And who are we to disobey? In the next few steps, you make your Rails application say hello; and in doing so, you learn a few new concepts. Your goal is to have a request with the URL http://localhost:3000/salutation/hello respond with a friendly “Hello World!” message.

First things first: Stop the web server by pressing Ctrl+C in the command prompt window. That should bring you back to your prompt.

Notice how easy it is to start and stop a local server? That’s the whole point of the built-in server in a nutshell. You shouldn’t need to be a system administrator to develop a Rails application.

Generating a Controller

Not unlike the rails command you used to generate your application, the rails generate controller command creates a bunch of new files. These are mostly empty, containing only skeletal code (often called stubs). You could easily create these files on your own. The generator merely saves you time and the effort of needing to remember which files to create and where to put them.

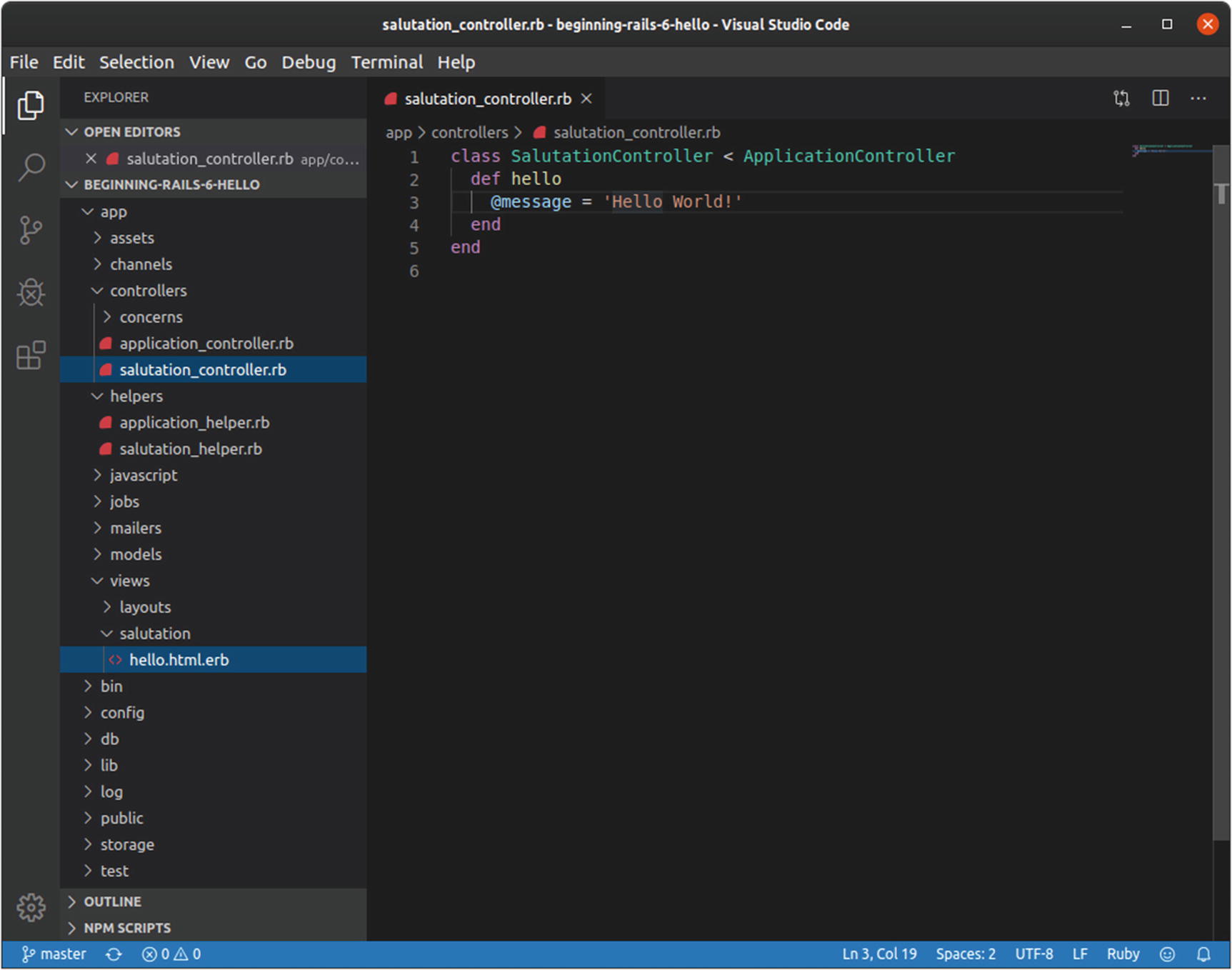

The app/controllers/salutation_controller.rb File

Creating an Action

The Updated app/controllers/salutation_controller.rb File: http://gist.github.com/319866

Actions are implemented as Ruby methods. You can always tell a method definition because of the def keyword. Inside the action, you set a Ruby instance variable called @message, the value of which you output to the browser.

Creating a Template

With your action successfully defined, your next move is to add some HTML into the mix. Rails makes it easy by separating the files that contain HTML into their own directory as per the MVC pattern. In case you haven’t guessed, HTML is the responsibility of the view.

If you look in the app/views directory, you see another product of the controller generator: a directory called salutation. It’s linked to the salutation controller, and it’s where you put template files that correspond to your salutation actions.

Because Rails allows you to embed Ruby code in your HTML by using the ERb templating library, you use the .html.erb (HTML + ERb) extension for your templates.

Controllers correspond to a directory in app/views

The app/views/salutation/hello.html.erb File: https://gist.github.com/nicedawg/0a45eae95abb3ff0e7993b9fd2120d59

The config/routes.rb File: https://gist.github.com/nicedawg/29b16f5d5fefeea7c3f5293b7dddb0da

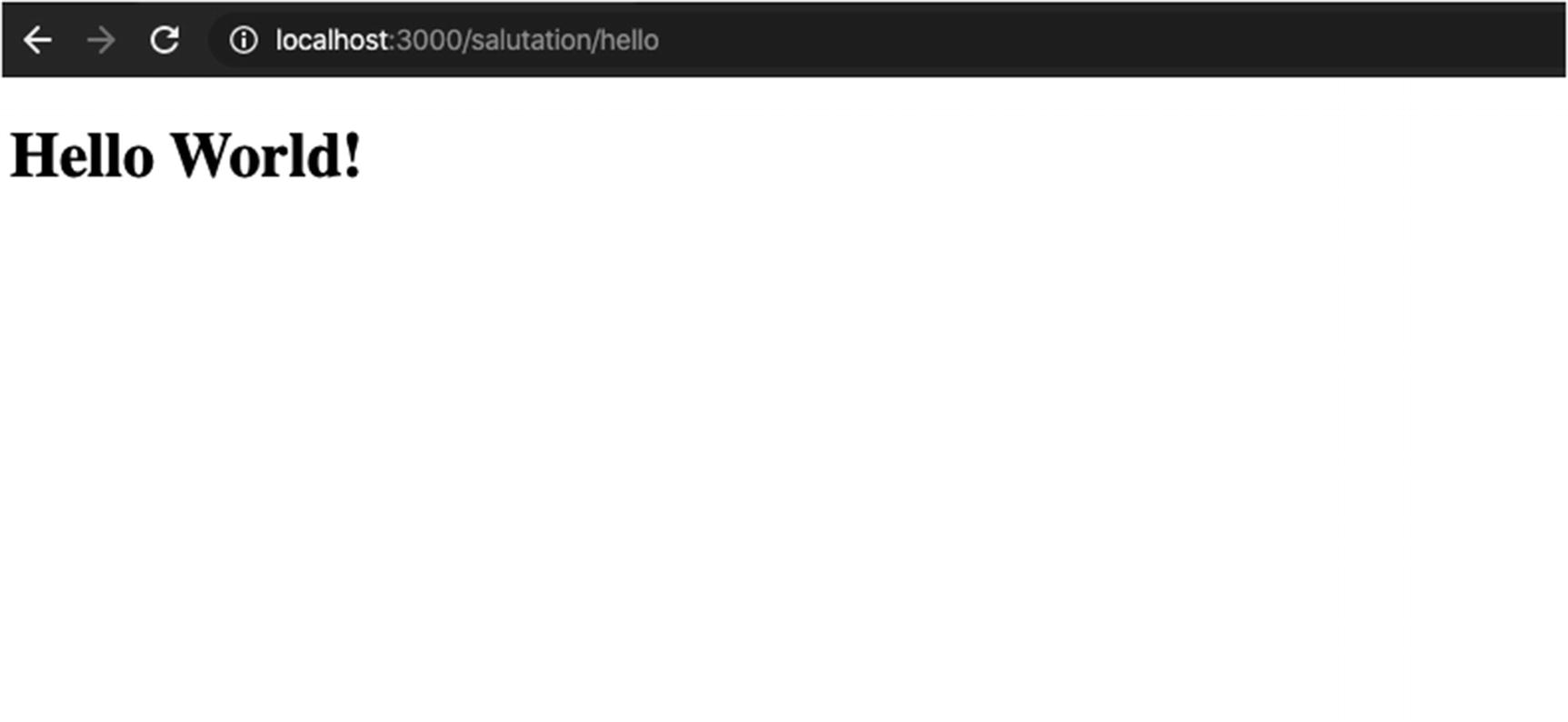

The “Hello World” application

Sure enough, there’s your greeting! The hello template reads the @message variable that you set in the controller and, with a little help from ERb, printed it out to the screen.

In case you didn’t notice, the URL http://localhost:3000/salutation/hello maps directly to the controller and action you created because of the change you made to your config/routes.rb file. Rails saw your “salutation/hello” route and figured out it should execute the “hello” action in your SalutationController. By following Rails naming conventions like this, you can avoid a lot of extra configuration code!

Summary

This chapter covered a lot, so you should be proud of yourself. You went from not having Rails installed to getting a basic Rails application up and running. You learned how to install Ruby and how to manage packages with RubyGems (which you used to install Rails). You also learned how to create a new Rails project using the rails command and how to use the generator to create a new controller. And you learned how controller actions correspond to templates. The stage is now set for the next chapter, where you begin building a more full-featured project.