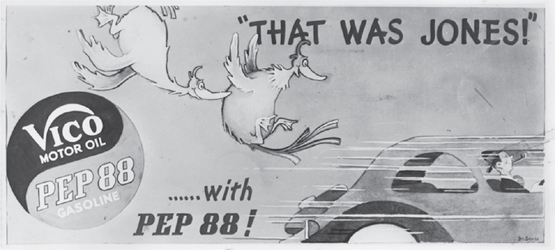

FIG. 12 Dr. Seuss, Vico Motor Oil advertisement, between 1930 and 1940. Dr. Seuss Advertising Artwork. Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego Library.

Dr. Seuss and His Wacky War on American Culture

The famed Beat writer, visual artist, and lifelong cat lover William S. Burroughs once wrote about how Nazi SS officers were initiated into the upper echelons of the Schutzstaffel. Over the course of a month, an officer was tasked with nurturing a cat. He would feed it, cuddle it, and in effect foster it into a pet. Then, at the end of the month, the SS officer was ordered to gouge out the animal’s eyes. The rationale was this: one “achieves superhuman status by performing some atrocious, revolting, subhuman act.”1 In another anecdote, Burroughs made no bones about his feelings for cat haters. “Cat hate,” he wrote, “reflects an ugly, stupid, loutish, bigoted spirit. There can be no compromise with this Ugly Spirit.”2 Given Burroughs’s penchant for the bleakest of satire, though, one wonders if there is any room for a comic spirit in this ugliness.

The wondrous work of Dr. Seuss—pen name for the zany, quasi-surrealist writer and artist and famed children’s book author and illustrator Theodor Geisel—stands as a rhetorical embodiment of both the catlike cunning in Burroughs and the comicality of a Burroughsesque cat. Notwithstanding some disturbing scenes from Junky (1953) that could make one think otherwise, Burroughs adored cats. He did not just like them for the sake of animal fellowship. He liked their characteristics. He appreciated their beautiful rage. Their awkward grace. Their reputation for so thoroughly cleaning themselves. Their willful abandon in flights of playful fancy. Their killer instincts. Their gentleness. Their independence. Their role as our “Familiars,” if not our “psychic companions.” And, à la Mark Twain, their amoral moralism. Now, Burroughs and Dr. Seuss were World War II–era contemporaries, but they were not associates or even friends. If they shared anything it was an affinity for the madcap (and, indeed, the mad cat)—and, perhaps, a certain dark humor that for one is manifest as droll saturnalia and for the other shows forth as comic phantasia. I call this reference to mind because Dr. Seuss eventually took on the cognomen “The Cat Behind the Hat,” whereby the figure of the cat became something of an alter ego for a man that the president of Dartmouth College in 1955 dubbed “the creator of fanciful beasts.”3 I call it to mind, too, because such fancifulness and beastliness animate the comic abstractions of national character that pervade the caricatures of Selves and Others in Dr. Seuss’s entire oeuvre. Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures deal with the sometimes strange, if not deranged, mergers that must take place for persons to take up nationalistic principles as the ideational analogues to identity politics. Put differently, Dr. Seuss’s artwork suggests that if some Other can provide a mirror for Ourselves, then caricature is no less the gritty lenses in ways of seeing collective selfhood.

The figure of the cat is an apt contact point in this setup. Cats have a storied history in myths and metaphors of curiosity, mischievousness, regeneration, and even languor. Dr. Seuss’s own Cat in the Hat exemplifies the feline trickster that makes messes but also cleans them up, sometimes for the fun of it and sometimes for the purpose of taking the message to Garcia, so to speak. The humor here also sometimes reworks what Philip Nel describes as Dr. Seuss’s “racial imagination,” which coalesced the discomfiting stuff of Jim Crow, minstrelsy, and blackface into an “embedded racist caricature in Geisel’s unconscious” but nevertheless opened up the possibilities of caricature’s comic disruptions.4 Cats have numerous hallmarks in this sort of comic arena. Behemoth is a shapeshifting, therianthropic, ungodly fiend of a creature at the center of Mikhail Bulgakov’s 1937 novel The Master and Margarita. But he was also a brazen jokester who regularly played the fool and the beastly “man” of humor among the retinue of Woland, a demonic professor who serves as executor to a cultural grapple with good and evil. Then there is Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat, who appears as an illusionist with regard to the rules in Wonderland. In each instance, the cat is an idea attached to an image. The fatuity to be found in Faustian bargains, for instance, brings the comicality of Behemoth’s clownings around into sharp relief. The grin without the face invokes the mirth of going mad as well as the power in seeing madness in oneself. The comic displacements inherent to a maudlin mouser and a crazy, discarnating grimalkin also signify a relationship between the thing and the other thing, the Self and the Other. We are what we are not, in other words, just as the Cheshire Cat is Dinah, but in a “world of alter egos and mirror images” that seems to parallel an alternate reality.5

In steps Dr. Seuss, who was seen as a weirdo in the World War II era and often rejected as an outsider with an odd sense of humor who dabbled “in far too much fantasy and far too little status quo moralism.”6 Dr. Seuss in arte very often seems to be the cat making mischief or serving as the subject of wonder.7 His art was the art of self-caricature in that it entailed caricatures of the very image and idea of selfhood. The Self is redrawn as the Other, recast as a comic abstraction. This was apparent in an illustration Dr. Seuss drew of himself and contributed to the July 6, 1957, issue of the Saturday Evening Post in which he is a cat in a hat seen in side profile from the neck up affecting a side-eye.8 His attention to selfhood is overt, too, in his nonsensical imagery that somehow makes sense of an absurd world. Dr. Seuss’s caricatures display a simple wisdom about human conduct and cultural consciousness that can be missed if one gets lost in the rhetorical weight of weirdness.9 Accordingly, Dr. Seuss follows the line of Twain, channeling the cat as a comic foil for grappling with the “atrocity of atrocities, War,”10 and its effects (or defects) on national character.

Indeed, the Seussian worldview is wackiest in the caricatures that fill out a collection of wartime editorial cartoons appearing in the newspaper PM, from January 1941 through January 1943. Philip Nel has argued that World War II occasioned the cultural moment that really made Theodor Seuss Geisel into Dr. Seuss.11 For sure, Dr. Seuss was inflamed by the rise of Hitler and the escalation of Nazism. Both represented human cruelty and out-of-the-ordinary worldviews beyond even his wildest fantasies. Both also constituted a real threat to the American Way. Equally as true is the disgust Dr. Seuss held for those Americans in whom he saw an Ugly Spirit of anti-warism, which he took as a sign of human failure in the fight against Evil and Folly. So, before he became an icon of children’s literature, Dr. Seuss traded in his childlike imagination for a more catlike, or crafty, art of caricaturing American war culture. He did so with what he described as “frantic fervor,”12 regularly targeting rodent “Japs” and serpentine Nazis and the Devil incarnate Hitler, and thus feeding into rampant, racialized rhetorics of nonhuman animalism (including references of enemy others as rats, apes, and imps) so prevalent in World War II discourse. Dr. Seuss likewise alluded to elements of foreign disease and entomological warfare, especially with images of infectious agents and gross insects. Yet, as ardently, he drew American Others as Appeasers, Isolationists, Weepers, Fifth Columnists, and more. Plainly, Dr. Seuss used the Good War as a bleak occasion to put American national character in the comic looking glass.

This chapter attends to the animal, machine, and foul oddities in the wartime caricatures of Dr. Seuss. The humor in them is uncomfortable. It is based on the rhetorical act of simultaneously identifying and disidentifying with national character in the name of War against Evil. Like Burroughs’s or Twain’s cat, Dr. Seuss uses caricature to look down on his fellow countrymen. He does so first and foremost with bird imagery. Birds are central to US American iconography and ideology. They are providential. The bird is also, in Twain’s words, the one creature that inspires a “wriggle” in the cat, provoking the spirit of action most powerfully when the spirit of lassitude seems to prevail. With bird-like creatures as well as other monstrosities, Dr. Seuss caricatures everything from pacifism to nativist politics. In the end, though, the humor in his wartime artwork reveals the idea of going to war as a means of safeguarding US American democracy. His comic alterity urges a way of seeing the world inside out, and of judging people for how they live out their principles in public. Does it sometimes use the comic license to exploit a state of exception in promoting racial, ethnic, gender, and other stereotypical sources of affective zeal in collective selfhood? Certainly. Does Dr. Seuss sometimes come off as a warmonger? Yes. But his humor is ultimately about uniting against the dire consequences of division and defeatism. That the United States should wage war against the Axis powers was a foregone conclusion for Dr. Seuss. Madcap were those who willfully ignored the threat of a mad brute and his Kultur. Out of whack were those who ran afoul of foundational principles of freedom and equality, such as people like Charles A. Lindbergh, institutions like America First, and newspapers like the Chicago Tribune. With a sense of humor full of rhetorical weight and whimsy, Dr. Seuss was able “to prod an unchecked nation getting too comfortable with itself, and viciously question the principles at its core.”13 The result is a view of World War II–era American national character in the comic looking glass, wherein odd amalgamations recreate even as they disconcert images of This and That, Self and Other, Us and Them. In Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures, US Americans are cats that have eaten canaries. To see this is to first see 1940s American war culture a bit out of whack.

Seeing World War II Through the Wrong End of the Telescope

Meet Sam-Bird. He is but one of Dr. Seuss’s strange caricatures of wartime national character. While his morphology is unclear, he is clearly an eagle that has become just an ostrich by another name, tricking US citizens into believing that democracy at any level is at all noninterventionist. To preserve the democratic spirit, for Dr. Seuss, is to take action, even if through war as a last resort.

This action orientation is the peculiar burden that democracy places on the proposition of war, and likewise the burden that war places on democratic principles. While democracy offers “the best political medium through which to incorporate strife into interdependence and care into strife,”14 war intensifies the projection of democratic selfhood as itself a site of conflict—in nativistic terms (like those of isolationists who fulminated about American internationalism), racial terms (like those in discourses of “The Jewish Problem” and “Race Hatred”), and so on. Sam-Bird embodies this conflict. In a cartoon from late September 1941, Sam-Bird stares into a carnival mirror—an “Appeaser’s Mirror”—to discover that he is a decrepit, battered, and bruised old bird with a long beard and a wooden crutch. “Jeepers!” the bird exclaims. “Is that Me?” Above the mirror is a placard that reads: “Take one look at yourself and despair!” Dr. Seuss makes a direct appeal here to the wake-up call he imagined Americans getting, and the kinds of things Flagg imagined wartime cartoonists making people see, when they realized the consequences of pacification as a modus vivendi for attaining peace. He also abstracts an image of the United States nation-state as seen through the eyes of others. The mirror shows Sam-Bird his true self. This was a projection of what could have been. It was also a provocation to consider whether or not an idealized reflection of national character is actually an ugly one. Peace might be the ideal, in other words, but a “good” war might be the only way to take care of a “bad” reality. Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures disfigure organizing principles. Unpopular as it might be for ideals of democratic agonism as an antidote to armed conflict, Dr. Seuss’s point was that entry into World War II would guarantee the continuation of democracy, or at least give it a fighting chance. Differences in opinion be damned when it comes to wartime Americanism, he seemed to be saying. The American Republic comes first.

Something weird happened the month before Sam-Bird saw his distorted reflection. The HMS Prince of Wales was moored in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, alongside the USS McDougal. A meeting was to be held between Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt. It eventually resulted in the Atlantic Charter. At a certain point on the day of the meeting, “Blackie” walked across the gangplank as if to board the American vessel (and this as the American national anthem bellowed from the decks of the British battleship). Seeing this, Churchill hurried to the footway to prevent Blackie from going aboard. An iconic photograph captures Churchill petting Blackie’s head. Blackie was a “ship’s cat.” Such cats have ancient origins, serving as the spirit animals that were supposed to ward off bad luck. Practically, a seafaring cat can be used for pest control, keeping vermin (like rats) from damaging a ship’s infrastructure, getting into the crew’s food stores, and spreading disease. Symbolically, cats like Blackie embody a rhetoric of friend-enemy relations, protecting a ship (of state) against being damaged from within while at the same time projecting an air of self-protection. They also embody a comic relationship between humans and nonhuman animals, which Churchill once expressed: “Cats look down on us,” he reportedly said while giving the fiancé of his daughter, Mary, a tour of Chartwell Farm. The same could be said of Dr. Seuss’s condemnatory caricatures.

Together, this catlike spirit and characters like Sam-Bird establish a basis for seeing Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures with a sense of humor that combines what George Creel called the “Gospel of Americanism” and the “war-will” of a democratic people. One from October 1941, just a few months after Blackie walked the gangplank in Newfoundland, features a cat looking on in dismay as a woman in an America First blouse reads a book to two young children. The book was Adolf the Wolf, with the head of a wolfish Hitler gracing its cover. The woman reads that the fascist wolf “chewed up the children and spit out their bones.” This was okay, she assured, because they were “Foreign Children.” For the nativist committee that pushed a noninterventionist approach to US entry in the war on grounds of national interest, many critics at the time saw the America First agenda as isolationist at best and pro-Nazi at worst. Dr. Seuss took a different tack, portraying nationalistic selfishness—particularly in the face of a war propelled by the tenets of Nationalsozialismus—as self-defeating for both the survival of democracy and the sanctity of American national character. It was akin, in Dr. Seuss’s words, to seeing the world through the wrong end of the telescope.

Of course, Dr. Seuss demanded the sort of fantastical thinking that sometimes requires “wrongheaded” perspectives. But his view was toward the shortsightedness he saw in those who could not or would not imagine the relationship between a democratic ethos at home (and abroad) and the threat of global warfare. So, he strove to telescope an alternative viewpoint, which is to say that he worked to portray the collisions, mergers, and forces of togetherness that telescoping can also entail. To see through the distorted lens of caricature, then, is to adopt a far-seeing perspective while maintaining a sense that things afar are closer to home than they might appear. Dr. Seuss was goaded on by the prospect of a global order organized by Hitler. He viewed Nazism as the antithesis to Americanism, particularly given its subjugation of a people under the iron umbrella of an omnipotent State and a supreme leader. Fascism embodies a myth of the Nation, lock, stock, and barrel. As Roger Griffin describes it, fascism is a palingenetic form of populist ultranationalism.15 Before the United States entered World War II, there were fears expressed by some cultural commentators and reporters for the American press (among them, famed minister Halford E. Luccock) that if fascism ever made it to America it would be called not fascism but rather Americanism. Dr. Seuss reflected these expressions. He was fearful that wartime notions of American exceptionalism were doing less to re-enliven the democratic roots of character, civic duty, and nationhood than the scourge of racialized, ethnocentric identitarian politicking. Surely he understood that an American Empire could look and feel egalitarian even as it stirred the body politic into a war frenzy in the name of peace and liberty. However, Dr. Seuss saw troublous predicaments in using the proclaimed foundational characteristics of US Americanism as pretexts for keeping Great Democracy to itself. He therefore saw homespun war politics as tragically farcical when Americans seemed to imagine that democracy is not always (if ever) what Henry Hazlitt dubbed in September 1940 an “alternative to war.”16 For Dr. Seuss, entry into world war as a pledge of allegiance to the American Way was what the tripartite of relief, recovery, and reform was for Roosevelt in 1932: “a call to arms.”17 Dr. Seuss’s caricatures thus took on the ethos of Burroughs’s cat. It was not enough for a person of American character to simply seek safety at home or even, if enlisted in the war efforts, to provide services; one must offer the Self. This is how Dr. Seuss telescoped his view of national character. Before delving into even more details of Dr. Seuss’s caricatures, it is worth dwelling on this telescopic view of comic imagery.

The culture of war underwrites such a Seussian comic framework. If US entry into the First World War was predicated on making the world “safe for democracy,” in World War II the organizing principle of democracy itself had to undergo a solemn militarization. The official national stance was antiwar. But in a fireside chat on December 29, 1940, President Roosevelt acknowledged that war production was simply “realistic military policy,” expressing an unhappy truth that implements of combat could create an “arsenal of democracy.” Hence the rise of the America First Committee (AFC) and its principles of national fortification and armed neutrality. The AFC was founded in September 1940. Its most vocal and high profile member was Charles A. Lindbergh, who used his fame from aviation as a takeoff for serving as the advocacy group’s chief spokesperson. Other notables included Senators Gerald P. Nye and Burton K. Wheeler, and publishers Robert R. McCormick (of the Chicago Tribune) and Joseph M. Patterson (of the New York Daily News). These individuals became some of Dr. Seuss’s leading stooges, exemplifying the so-called Fifth Column, its subversion of popular opinion, and the antidemocratic orientations of nativist groups. Dr. Seuss sought what James T. Sparrow calls a “warfare state,” or a sense of nationalistic readiness and a mass of citizens already initiated in a democratic war culture. For Dr. Seuss, going to war in the name of democracy meant protecting the home front from those anti-war factions who, with their live-and-let-die attitudes, were no better than foreign enemies. In 1941, some newspaper editors such as Benjamin Frazier and Joseph Stanley of the New York Times were dubbing isolationism a form of cultural imperialism and civic complacency a manifestation of national betrayal. These sentiments echo those of Herbert S. Houston, executive committee member for the League to Enforce Peace during the First World War, who saw the resolution of war as an agent of Americanism. The kind of patriotism and self-sacrifice that comes with democratic organization is, as the argument goes, also necessary in warfare.

Everything with regard to isolationism changed after the attack on Pearl Harbor (notwithstanding Kristallnacht). In late 1939, public discourse in the United States circled around Roosevelt’s “military Magna Carta” and how that might square with the image of a peaceful, democratic America. Roosevelt promised to keep the United States out of war, even though news outlets like Life and writers like Henry Luce (who thought that isolationism represented everything wrong with American nationalism) questioned his neutral stance,18 and even though rumors of a Fifth Column were buttressed by warnings about “espionage, sabotage, and subversion as favored devices of the ruthless Huns.”19 The bombs from the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service were dropped on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. American isolationism ended on December 8. By August 16, 1942, the head of the Office of Facts and Figures and Assistant Director to Elmer Davis of the Office of War Information (OWI), Archibald MacLeish, proclaimed it dead. World War II quickly became a “new” war for democracy. Armed conflict was a necessary evil.

Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures appeared in PM (1940–48), a left-leaning newspaper that abhorred a print culture built on advertising dollars and shaped its editorial prerogatives toward the public interest. It was backed by investor Marshall Field III and started by Ralph Ingersoll, a former managing editor of Time, Fortune, and Life. Emphasizing drama, storytelling, opinion, and pictures, PM combined a nineteenth-century spirit of editorial reporting primarily through “picture news” with “the wit of a magazine and the pace of a daily.”20 Still, it was essentially a medium for supporting labor unions, propounding New Deal politics, expressing a raw hatred of Hitler, and reviling anything or anyone that seemed to trade in democracy for fascism—especially under the guise of a nativist, antiwar doctrine.21 PM promoted a view of national character that countervailed the OWI and its “idealistic characterizations of American life.”22 The OWI shaped public opinion, not unlike the Committee on Public Information. But it also had the burden of ill repute that hung over the comparable propaganda arm during World War I. James Montgomery Flagg’s version of Uncle Sam was alive and well, along with its I-Want-YOU appeal. The genre of “picture news,” however, had become a cultural industry by the middle of 1942, with cartoons providing a resource for “humoring” the daily chronicle of complex happenings at home and abroad. Caricatures provided a distorted mirror for seeing civic selves in that chronicle.

Caricature made war real for those not on the battlefront and so complemented “the new visibility of the labor of cultural production.”23 PM was part of the Popular Front. Public artists like Dr. Seuss were cultural workers as much as they were citizens engaged in war work. Dr. Seuss’s caricatures channeled a growing nationalistic image of the “democratic character of American culture” in the sense that “democracy begins at home.”24 His caricature campaign was associated with an apparatus of newspapers, film studios, and magazines that converted an idea of “cultural democracy” into a culture of war.25 Fantastical as they were, Dr. Seuss’s caricatures offered a way of showing and telling war culture for what it was. This does not mean that Dr. Seuss avoided the slippery slope into ethnocentrism and racial prejudice. As Richard H. Minear laments, “it is a surprise that a person who denounces anti-Black racism and anti-Semitism so eloquently can be oblivious of his own racist treatment of Japanese and Japanese Americans.”26 Granted. But it is doubtful that Dr. Seuss was oblivious. For one, while he certainly gave himself over to the demonology of Us–Them battle cries, Dr. Seuss came around to the better angels of his nature in making appeals to what he saw as the freedom-loving family of human beings.27 For two, he made a conscious artistic choice to exploit the rhetorical trappings of comic morphology. The examples that follow make manifest just how powerful depictions of “foreign” others can be for positive depictions of a nonetheless abject national character. Such is the burden of caricature. Such is also the backdrop for Dr. Seuss’s development as a caricature artist.

Dr. Seuss has a somewhat strange professional biography. He grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. After college, he became an illustrator for publications like Life, Judge, the Saturday Evening Post, and Vanity Fair. At one point Dr. Seuss did a stint in graduate school at Oxford University but dropped out to become a full-time cartoonist. Soon thereafter he gave himself the title “Doctor” and eventually earned the moniker Poet Laureate of Nonsense. Dr. Seuss was something of a struggling artist until, in the mid-1930s, he dabbled in some nascent political cartooning with a mostly forgotten comic strip, Hejji. At the center is a young boy who sails aboard a birdlike creature to a strange place, the Land of Baako, which—as one strip tells it—is essentially shut off from the world and made up of human and nonhuman creatures with “strange ways,” like whales that swim in lakes at the tops of volcanoes. But even in its nonsense the strip is not so strange. For instance, upon arriving in the Land of Baako, the young boy is captured by the local people, dubbed a “foreign fool,” and brought before The Mighty One who is reputed to be in a “dark, dark mood.” The tale ends well enough, and the boy reconciles with the rajah. Still, it amounts to a not so subtle account of how human beings get along with one another. Baako, as it happens, is a Hindi word meaning loose tongue. Here, it is a metaphor for the cultural politics of “race, representation, and power.”28 It also bespeaks the comic confusions that Dr. Seuss elsewhere portrayed in paintings like “The Tower of Babble,” which was done sometime between 1930 and 1940.29 This cartoon image encompasses much of the visual imagery of Hejji and depicts a confused world full of odd beasts, weird contraptions, bizarre material conditions, and yet all too familiar stratifications. It is almost a metacaricature of caricature itself as a confusio linguarum, or confusion of tongues, mocking the sorry state of human affairs in a manner made more significant given its creation in the chiasma of two world wars.

These comic politics of depiction drive Dr. Seuss’s storytelling sensibility. About two years before he began his own caricature campaign, in 1939, he published a graphic novella of sorts, The Seven Lady Godivas: The True Facts Concerning History’s Barest Family. It was a complete flop, hitting the shelves with little fanfare. But it captures Dr. Seuss’s appreciation for being who we are without frivol, froth, feather, or fuss. It was a retelling of an eleventh-century legend that Dr. Seuss made into a story of honor-thy-father sisterly love and recollection of the Peeping brothers (including Tom). The book was full of caricatures made for adults, and it previewed some of the touchstones that typify his famous children’s books: quirky nonce words now in common usage, chimerical creatures, zany contraptions, and entire worlds comprised of wit and whimsy. It also exemplified the familial devotion that Dr. Seuss maps onto national politics, especially with its basis in warfare (Lord Godiva, father of the seven ladies, dies after being flung off the horse that was going to take him to the Battle of Hastings), its odd eroticism (the sisters parade around naked, each courting a brother from the Peeping family, though expressly unwilling to marry following a pledge to their late father), and its orientation to the public good (the marriage embargo is stipulated by the sisters’ noble quest for “Horse Truths”). To boot, one of the cartoon images features the seven sisters encircling their father, who is splayed out on his deathbed looking unnervingly like Uncle Sam in armor. The grotesqueries here mirror the grittiness of his commercial artwork.

Before getting into children’s books and editorial cartoons, Dr. Seuss was known as a wacky adman. Among his many clients were Ajax Cups, Ford, General Electric, Holly Sugar, NBC, and Standard Oil. The most prominent of his ad artwork was that done for Flit, a popular insecticide manufactured by Standard Oil in the late 1920s. A campaign from 1928 made Dr. Seuss “an icon of advertising.”30 It familiarized publics with his witticisms and his quirky worlds inhabited by customers who likely thought, “Quick, Henry, THE FLIT!” when they thought of how to exterminate pests. This slogan accompanied cutesy albeit crude caricatures of insects in what became a standard for humor in print advertising. Dr. Seuss’s ad work reveals how indelicate visual metaphors used to sell consumer goods could also be used in caricatures aimed at selling war. A few things therefore stand out in these commercial beginnings.

First, the ads ground his depictions of proper conduct on the home front. In a series of pictures he drew for Holly Sugar, for example, a variety of creatures are faced with a bitter-tasting food item. In one, a frustrated bird chews a cherry. In another, a giraffe plucks a green grape from a woman’s hat. In yet another a redheaded human being cringes over a strawberry. The audience is reminded: “All they Need is . . . Holly Sugar” to sweeten any sour deal. A similar sentiment is advanced in ads like those Dr. Seuss created for Standard Oil, which portray the wild glee of Brother Jones as he whips by “onlooking birds and other creatures” after purchasing Pep 88 gasoline or Vico motor oil (fig. 12).31 These animals later become the wartime voices or eyes of judgment on the blunders of American citizens.

FIG. 12 Dr. Seuss, Vico Motor Oil advertisement, between 1930 and 1940. Dr. Seuss Advertising Artwork. Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego Library.

Second, the ads prefigure the sorts of odd monstrosities that Dr. Seuss often used to animate the degeneracy of ostensibly “good” citizens, rotten people or groups, and enemy combatants. In one of his tamer images for General Electric, Dr. Seuss drew the head of a “Bulbsnatcher,” or “Domesticus Americanus,” which appears as a shamed sculpture sharing wall space with a taxidermal bear, sheep, moose, and lion (all of which are grinning at the human pate). Before them all, two businessmen discuss how just it was to scapegoat the Bulbsnatcher in such an extreme fashion, agreeing that “the Little Neck Explorer’s Club went too far in its punishment of the member who persisted in taking lamp bulbs from one socket to fill another.” Activities on the home front animate the consequences they arouse. The brashness of these whimsical animals underscores the serious side of a heinous characteristic of the typical, stingy American man.

A third and related point has to do with Dr. Seuss’s advertising raid on insects. His entire cartoon catalog for Flit merits sustained attention, but for the purposes of this chapter it is most relevant to highlight how it emphasized the elimination of vermin. This very theme was applied to domestic battles against enemies within and “other” cultures that threatened the American way of life with their “subhuman status.”32 In one ad, Robinson Crusoe is pictured swimming to the shore of a small island. On it is an indigenous Black man who unequivocally fits the racist and offensive coon stereotype, with big lips, large earrings, and tribal garb. Crusoe seeks safe haven from a sinking ship, which descends into the ocean in the distance. But the Black man turns him away, telling Crusoe to return to the ship and come back with Flit to rid the island of pesky flies. Here, a pesticide is upheld as a symbol of civilization. At the same time, the Black man is a contrarian who forces Crusoe back into a dangerous situation from which he just escaped, and for nothing more than a selfish interest in ridding himself of annoying insects. In another, a tightrope walker comes under assault from a grotesquely large and seemingly bioengineered mosquito with a massive harpoon-like blade for a nose. The funambulist stumbles in horror while a ringmaster gazes up from below in comparable dismay. In large, bold letters that appear above a bug sprayer and a canister of insecticide is the admonishment: “Quick, Henry, THE FLIT!” Both ads capture Dr. Seuss’s contempt for complacency and his sense that willful ignorance makes those things right in front of you the hardest to see—perhaps especially when they are buzzing in and around your head.

Then there is Dr. Seuss’s machine imagery. In another ad for Standard Oil’s Essolube, an oversized, ghastly cat tampers with a car engine as a white male driver looks on in shock. The cat grins widely as he uses his forepaws to abrade the man’s motor. A caption above the image advises, “Foil the Moto-raspus!” The Essolube, not unlike Flit, destroys pests. It is also the way for a flock of satisfied birds to fly south in another ad when signs for Essomarine oils and greases line the coast like signposts for a charter. In later wartime cartoons, such machinery indicates a broken body politic, with political solutions as mechanisms for greasing the wheels of war. This machinery, like animalisms and contagions, made enemies and enemy principles into what Kenneth Burke might recognize as “Hitlerite distortions,”33 exploiting a comic aesthetic of hylomorphism in images and ideas of national character.34 These rhetorical conventions are everywhere in Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures, the modus operandi for which is garnering humor from images of an aggregated “us” in the comic space of inimitable tragic farce.

Humor in the Comic Abstraction of Coming to Americanism

There is an undated watercolor painting from Dr. Seuss’s secret archives. It is named “Manly Art of Self Defense,” and it features a boy squaring off with a cat.35 Both are wearing oversized boxing gloves. Both, too, look utterly awkward. The shirtless boy appears almost dainty, with one gloved fist held out in front of the cat’s face. The pugilistic cat is standing on its hind legs, eyeballing the boy’s glove with a mix of surprise and unease. The cat’s gloved front paws are pointed down but the animal appears ready to pounce, except that “the boy does not grasp the harsh reality of boxing,” and the cat realizes it. Together, the cat and the boy make up a sort of doubling with naïve insouciance about combat and self-motivated territorialism. On one side is a boy who is not even aware that he is about to come to terms with his own selfhood. On the other is a nonhuman animal that seems torn between taking the boy down and turning away.

What matters in this setup is comic abstraction. According to Roxana Marcoci, a comic abstraction upsets normative imagery insofar as it is made “to perturb, insinuate, tease, and demystify assumptions.”36 Dr. Seuss’s approach to caricature is nothing if not perturbing, et cetera, built as it is on a pretension that the Other can and should be seen as a measure of the Self. Furthermore, Dr. Seuss’s caricatures abstract imagined characteristics of, say, a category of people (be it a precocious boy or a national body politic) by merging them with the fantastical and absurd. As one art columnist wrote of Dr. Seuss’s ad work: “He exaggerates, he distorts, he contrives figures more fantastic than those of the Dadaist or the surrealist.”37 Humor emerges out of the pretense that resemblances and distorted mirror images show us more about ourselves than reflections of the “real” thing. It is resident in what is out of whack, especially rhetorical judgment. In Dr. Seuss’s caricatures, there is proof for the strange sense in seeing other-wise.

The otherness of humor is an important hallmark for considering how the fantastical functions as a sort of comic sublime that at times reroutes and at other times completely refashions more conventional cartoon takes on the war culture of the day. Dr. Seuss was not doing the kind of work so common to that of cartoonists like Bill Mauldin, David Low, and Herblock. Mauldin, for instance, did war coverage for the 45th Division News newsletter and Stars and Stripes, placed great emphasis on the combat experiences of US American soldiers, and—through characters like Joe—chronicled the human element of just war as it was fought on the front lines. Low worked in England. He was widely known as a warmonger who harped on the international stakes of taking on fascism and going to war against the Nazis in order to preserve a liberal, democratic order.38 Low urged American cartoonists to ditch the image of Uncle Sam altogether. He saw realism in caricature as a means of expressing the rationales for war efforts, especially relative to reportage on Nazi ideology, the strongman politics of Hitler and Mussolini, extermination camps, and more. Comicality, for Low, was a way to capture the atrocities of both culture and combat as it emerged out of Nationalsozialismus, and to humor a notion of victory at all costs. Herblock was not unlike Low and Mauldin. He was a cut-from-the-cloth interventionist. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning in 1942 and drew official cartoon images for the Army. The so-called “Herblock Image” endured throughout the Cold War era. In World War II, this image was over and again one of the evil other. Herblock regularly drew Hitler and the Nazis facing off with US American soldiers or committing atrocities. His realism dwelt on the fact that there is evil in the world, and there are evildoers who justify war production. Dr. Seuss was not indifferent to these orientations. But he took his own caricatures another way.

Dr. Seuss’s caricatures set forth rhetorical judgment in the space of the superficial, and humor in the stuff of comic abstraction. Seeing is distorting. Deleuze says something similar when he dubs humor “the art of the surfaces and of the doubles.”39 Deleuze sees in humor, indeed on surfaces, the deepest of human matters. No surprise that he relies on a close reading of Lewis Carroll’s tales of Alice in Wonderland to make his case. In Wonderland are multitudinous admixtures of images and ideas. What is more, animals dwell in the depths of the rabbit hole, wherein depth itself becomes surface. Alice’s plunge is defined by interpenetrations and coexistences. One sees them not by simply going underground but rather by peering through the looking glass. Dr. Seuss’s caricatures amplify an American Wonderland, transmogrifying the phrase “through the looking glass” into a visual metaphor for seeing the depths of surfaces. They are comic abstractions in which human characters become Other by becoming Animal. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his use of so many birds to bring wartime national character to bear, particularly in terms of the cultural warfare that is carried out at home while war is waged abroad.

BIRDS OF A FOLLY

On May 21, 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh flew a solo, nonstop flight across the Atlantic to much fanfare. Lindbergh later became a student of aviation and, by the late 1930s, an outspoken critic of the Roosevelt administration and pro-war factions. He was also widely regarded as a racist (even a white supremacist with Nazi sympathies). In October 1939, Lindbergh delivered a radio address entitled “Neutrality and War” celebrating the racial characteristics of American exceptionalism while laying out a program for nonintervention. Less than two years later, Lindbergh spoke as the proxy for the America First Committee (AFC), condemning “war agitators” like British Jews and New Deal idealists for “subterfuge” and “propaganda” that constituted a plot against America. Dr. Seuss saw it otherwise. In many ways, he foreshadowed Philip Roth’s 2004 historical revision, The Plot Against America, a novel that reimagines the outcomes of World War II as if Lindbergh ran against Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election—and won. In Roth’s account, the US government signs a treaty with the Nazis, ensuring a peaceless, fascistic American nation. For Seuss, a ploy to avoid war in the name of Americanism was itself a plot against America.

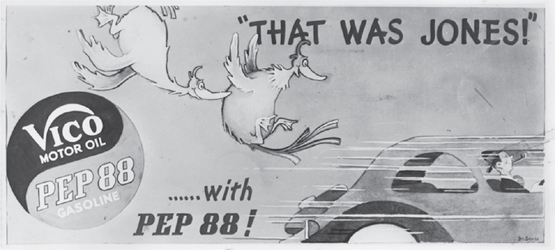

Dr. Seuss’s wartime birds capture the wayward folly of those who seemed to simply look on—or look away—as war raged on overseas. Lindbergh was an early cudgel for this encapsulation. One cartoon from April 1941 displays Lindbergh in a small prop plane flying above an American city towing a banner that reads, “It’s Smart to Shop at Adolf’s,” with the qualifier, “All Victories Guaranteed.” A flabbergasted bird floats in the clouds and looks on as a closed-eyed Lindbergh flies by. The bird is a symbol of freedom, and a countervailing force against the isolationist movement that Dr. Seuss witnessed taking flight in the late 1930s. But Dr. Seuss’s birds do not fly. Consider another cartoon, which was published just days later. In it, an ostrich appears on a “Lindbergh Quarter” (fig. 13), stuffing its head in a pile of sand. Above the bird’s head, which is plainly visible despite being buried, are the words “In God We Trust (And How!).” A caption reads: “Since when did we swap our ego for an ostrich?”

FIG. 13 Dr. Seuss,“The Lindbergh Quarter,” April 28, 1941. Dr. Seuss Went to War. Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego Library.

The ostrich symbolizes the defaced currency of Americanism that is applied to the infamous aviator and his lobbying group. The bird’s eyes are closed. Its beak betrays a smile. It is puffed up even with its face down. Dr. Seuss’s ostrich mocks those who trade in the cultural purchase of American national character for anti-warism. The sublime meets the ridiculous here. First, the Washington Quarter had not even been in circulation a decade and already its luster was being stained, along with Washington’s foundational American sentiment that preparedness for war is preservation of peace. Second, the ostrich stands in stark contrast to the grace and glory of the bald eagle, never mind the stupefaction of the bird left in Lindbergh’s wake. Third, the flightless ostrich is known for running away from predators rather than engaging them. The image also exploits the mythic quality of ostriches burying their heads in sand to avoid (or ignore) danger. The Lindbergh Quarter doubles as the Ostrich Quarter. It visualizes the imprudence of miscalculations in wartimes. It likewise sets the stage for Dr. Seuss’s use of caricature to intervene with isolationism and its ethos of cashing in on US American freedoms without paying for them. The ostrich exemplifies a counterfeit national character.

The ostrich is a comic abstraction of civic dispositions. For instance, in his very next cartoon, Dr. Seuss depicted a vendor standing on a plinth fitting white male patrons for “ostrich bonnets.” Sharing his platform is a pile of ostrich hats and a sign that advertises relief for “Hitler Headaches,” with this guarantee from the Lindy Ostrich Service: “Forget the Terrible News You’ve Read. Your Mind’s at Ease in an Ostrich Head!” Two men wait in line. A third receives his bonnet, and from the foreground into the deep distance of the lower right frame is a row of ostrich-men, all of whom have their heads stuffed snugly in the sand. A caption reads: “We Always Were Suckers for Ridiculous Hats. . . .” Because the vendor is wearing a bonnet himself, it is unclear whether or not Lindbergh is the man behind the mask. What is clear, though, is that the features of both the man and the animal make up the crude madcap. What is also clear is the racial implication in this setup inasmuch as the ridiculous white men only see the world through their own eyes. Theirs is the outward projection of a simplistic, singular consciousness. The double-consciousness inherent to Blackness typifies and, in Black bodies, personifies the sort of doubledness that sets Black and white in conflict, never mind war and democracy. Dr. Seuss mocks the single-mindedness that shows itself for what it is in the white gaze of the comic looking glass. Tellingly, the ostrich hat retains the countenance already seen on the Ostrich Quarter.

Wartime miscalculations thus fold into mistaken identity. The Ostrich Bonnet betrays a public show of “unnatural” selection. Each man pretends to be part of the flock. However, the outcome is not so much power in numbers as it is political disempowerment in the self-satisfaction of blissful, even willful ignorance—a point reinforced by the collective loss of identity on display (all the ostriches look the same). A blind eye on the front lines, like a blind eye on the color line, is a losing proposition. What is Dr. Seuss’s point? Isolationists are ridiculous human animals, unable to separate themselves from their own egoism in order to appreciate the wider social, political, and cultural contexts of armed conflict and their relation to a more complex, more complete national character. A racial, if not imperial, self-consciousness actually betrays the weakness and cowardice of a purely self-interested nation. This is not confined to individuals. It is a cultural condition. In this context, it is a war culture. Furthermore, the bonnets attribute a certain effeminacy and ethnocentrism to isolationism, allegorizing the “true” character of white isolationist American men even as they hide their faces. As was the case in Flagg’s comic abstractions of national character, in Dr. Seuss’s early wartime caricatures is an image of comic shame.

Dr. Seuss’s ostrich imagery lampoons what it means to be ashamed of oneself in public. Unlike Uncle Sam’s “I Want YOU” image, which incites a sense of guilt in avoiding civic-as-military action, Dr. Seuss’s ostriches portray the conscious choice to resist war as a shameful vice that masquerades as a virtue. In some of his later cartoons, Dr. Seuss goes so far as to make the ostrich a caricature of fascistic invasion on the home front. Ostriches are an invasive species. Even Roosevelt imagined this possibility, as he said in his State of the Union address on January 3, 1940: “I hope that we shall have fewer ostriches in our midst,” he said. “It is not good for the ultimate health of ostriches to bury their heads in the sand.” Hence the men in ostrich bonnets. Hence, too, the “GOPstrich,” or what Dr. Seuss dubbed in October 1941 the “Offspring of the G.O.P. and the Isolation Ostrich,” embodying the official adoption of isolationism by the 1940s Republican establishment. By November 1941, however, Dr. Seuss began depicting the demise of isolationism by situating the ostrich in a museum exhibit. In it, the creature shares space with the skeletal remains of dinosaurs that are acting alive and heckling their new addition. The imagined extinction was portentous. Roosevelt had just enabled American merchant ships to carry armaments, Moscow remained under attack (and the United States had authorized a loan to the Soviets for defense), and the USS Enterprise was being mobilized for war. In a week, Japan would grow more belligerent. On December 1, Emperor Hirohito would approve hostilities against the United States as newspapers like the Seattle Star announced imminent danger with headlines like “WAR NEARS!” even as others touted the possibility for peace talks. It would not be long until evidence emerged of Japanese activity around Manila, and Hideki Tojo, a general for the Imperial Japanese Army, would ramp up rhetoric about purgation of Americans in the Far East.

Dr. Seuss declared this “GOOD NEWS,” and re-upped this sentiment the day after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, which he celebrated with a cartoon exploding the Isolationism Ostrich sky high. “He never Knew What Hit Him,” reads the caption. War, for Dr. Seuss, was the bygone conclusion of what many saw at that time as the ongoing fight to save Democracy by saving the American Way. Dr. Seuss’s praise for the “good news” of war was issued by “Sam-Bird,” a plump American Eagle with finger-like wings, a long neck, and a beard and top hat combination that codified his congruence with Uncle Sam. In June 1941, Sam-Bird could be seen sitting in a familiar position with eyes closed and finger-wings crossed. He is in a lounge chair, smiling as mortar fire blasts around his “Home Sweet Home.” Atop his chair is a tiny umbrella, the only “real” protection against the assault. As bombs burst around him and missiles whiz by his head, Sam-Bird comforts himself with a rhyme: “Said a bird in the midst of a Blitz, / Up to now they’ve scored very few hitz, / So I’ll sit on my canny / Old Star Spangled Fanny . . . / And on it he sitz and he sitz.” The whimsical verses imply a churlishness that reinforces the strange suggestion that the bird actually sits in a sitz (a domicile), if not a sitz bath (a treatment for aches and pains). Such a troubling portrayal of complacency evokes a sense that the war wary were doing more to enable the scheming of isolationists than to come up with a good way to intervene.

Across Dr. Seuss’s caricatures the eagle is sometimes the governmental apparatus of Washington and sometimes the anthropomorphic animalism of the nation itself. In any case, the eagle (like the ostrich) is a therianthropic shapeshifter that distills the organizing principles of a body politic even as it articulates the possibility of otherness on one hand and the value of seeing differently on the other. Dr. Seuss’s fear was that democracy and fascism were two sides of the same coin. On one side was the tragedy of antidemocratic cooperation. On the other, the comicality of democratic farce. His turn to eagles helped Dr. Seuss flip the coin, and the script, on the ostrich.

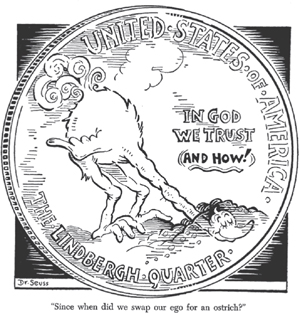

Here’s how: On December 9, 1941, Dr. Seuss’s eagle woke up. A cartoon, captioned “The End of the Nap,” shows Sam-Bird in a rocking chair (fig. 14). He is enormous, at least compared to five Japanese soldiers that are rousing him into a state of wakefulness. One pulls off his top hat and hits him over the head with a gavel-like mallet, signifying something of a day of reckoning. One is lighting Sam-Bird’s feet on fire with a match, while another saws the floor out from under his chair. Yet another shoots a pellet from a slingshot toward the bird’s bearded chin. A final soldier drills a screw through the back of the rocking chair and into Sam-Bird’s spine. The cartoon is a distorted mirror of Flagg’s well-known appeal to “Wake Up, America!” especially with the bird’s stern eyes and deep scowl. Even more glaring is the infantilized image of Japanese fighters who appear like children harassing an elder. On top of this is the fact that the soldiers are essentially clones of one another, underscoring Dr. Seuss’s racialization of the Japanese as unthinking look-alikes doing the bidding of fascists. The Japanese are a nuisance to Sam-Bird, resembling so many allied depictions of “Japs” as subhuman insects. Insects swarm. Like Dr. Seuss’s ostrich bonnet–wearing men, they are one and the same. The eagle, contrariwise, is an always-individuated, always exceptionally singular figure for US national character—until it is infested.

FIG. 14 Dr. Seuss, “The End of the Nap,” December 9, 1941. Dr. Seuss Went to War. Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego Library.

In the prewar period, Sam-Bird was a dodo. He was not unintelligent. He was just outmoded in his assumption that words could thwart war. On May 8, 1941, Dr. Seuss portrayed the American Eagle in his rocking chair with his eyes closed, his wing-fingers crossed across his belly, and his mouth agape spewing “Talk Talk Talk Talk Talk Talk Talk.” As opposed to the roused Sam-Bird, this one is much larger than his chair, has an extremely long neck (like an ostrich), and appears happy in his chatter. He is also alone, talking away in puffery that forms clouds about his head. The possible allusions are rife, from references to diplomacy amid Japanese aggression, to talks of trade embargoes and the security of military supplies shipments for European allies, to lend-lease deals, to Roosevelt’s closeted racism despite his good talk on race relations (some of his advisors thought it possible that there could be a “Black Cabinet” to counterbalance the “official” one), and even to his efforts to conciliate the prospects of armed conflict in his fireside chats. The eagle might not be Roosevelt.40 However, it exemplifies Roosevelt’s description of war as a matter of public debate. While Dr. Seuss supported Roosevelt and his New Deal ethos, he aligned himself with strong interventionist factions that had been situating the frights of warfare as the very reasons to fight. Freedom, for Dr. Seuss, justified the democratic politics of war. Roosevelt “talked a lot.”41 He was seen as much as a “good neighbor” as a commander in chief.42 As historian Alfred Whitney Griswold said of Roosevelt in 1938, the president was also a self-proclaimed opportunist—or, what Warren F. Kimball has more recently described as a “juggler” who “reacted, shifted, rethought, and recalculated.”43 His obsession with public opinion polls is thus unsurprising, and with it his request for a “Weekly Analysis of Press Reaction” from the Office of Government Reports. This left far too much wiggle room around a moment that demanded deeds over words. Dr. Seuss made this sentiment painfully obvious when he drew Sam-Bird on a stool, wearing glasses, and using an oversized military sword to literally split hairs with Hitler looking on.

The point is that birds represent Dr. Seuss’s caricatures as resources for regarding collective selfhood in a mirror, distortedly. The humor arises out of the comic differences in his bird imagery across its repetition. Humor, à la Deleuze, is an art of creating depth in surfaces. As a prime rhetorical feature of caricature, humor plays with surface features in such a way as to fathom depths. Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures plumb those depths by showing how American national character had sunk in accordance with a complacency and cowardice in antidemocratic attitudes that festered in the surface features of US Americanism. It is fitting in this regard that humor should also be recognized as a rhetorical “art of consequences and effects.”44 There can be humor in seeing something or someone out of its depths or, in this case, flitting away the conditions of possibility for democratic peace in the folly of world war. Democracy is a veneer that covers the threat of war. Dr. Seuss draws out a deep humor in recognizing how this ugly truth lies just below the surface of America the beautiful.

So it is that on January 1, 1942, Dr. Seuss drew a new image of national character. The eagle is gone (as is the ostrich), and bird imagery is all but flitted away for more realistic fantasies of enemy relations. In place of ostriches and eagles is Uncle Sam, who wakes to the New Year with a hangover. Sitting up in his patriotic pajamas, he rubs his face and finds his bed overrun by two serpents. Another worm-like creature sits atop the headboard. A starred and striped top hat rests at the foot of the bed, while Hitler (with the trunk and ears of an elephant on the body of a snake) sits coiled on Uncle Sam’s head. On his pillow is another serpent, most likely representing Hirohito or Shigenori Togo, Japan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. The skin of the Japanese snake is covered in Rising Suns, and his countenance bears stereotypically thin eyes behind a pair of wire-rimmed glasses, which sit on a pig-nose above buckteeth that protrude from a pursed upper lip. Serpentine creatures have invaded the United States’ most private of domestic spaces in this cartoon image. Or better, the nation has allowed itself to be assailed by a grotesque political culture. Dr. Seuss’s first day is a day of reckoning. It is concerning that Dr. Seuss’s caricatures rely so heavily on comic abstractions that both gloss over issues of homegrown nativism, racism, sexism, ethnocentrism, and more, and put “good” use to specifically racial and ethnic stereotypes as nationalistic markers. One can see why he did so, though. Caricature is Dr. Seuss’s mechanism for coming to Americanism. It is his vehicle for working through the ugliness that chafes at images and ideas of national character. It is his way of evoking a comic sensibility about the proximities between individual people and their bodies politic, and about rhetorical judgments we make of the unfunny attachments we have to certain modes of organizing ourselves into This or That assemblage. Caricature is, in many ways, a projection outward that doubles back with a comic take on the Self.

Such a doubled projection is apparent in Dr. Seuss’s shift from a Self-orientation to a wholly Other-directedness. This shift appears in caricatures that characterize “Jap” culture as an unwitting populace of bugs that cannot be appeased, only exterminated. Surely, there are obvious allusions to Appeasers and Isolationists on the home front, who are seen as infested with wrongheaded views about American democracy in action. But there are even more obvious articulations of American national character gone bad when corrupted by “insect enemies,”45 and then again by the sorts of war productions that yield cultural waste and industrial cruelties. I therefore turn now to the blighted selfhood that appears in Dr. Seuss’s caricatures of otherness—of insects and instruments of war.

BUGS, BILE, AND BIG WAR MACHINES

In shifting his attention to insect enemies, Dr. Seuss altered his orientation from warmongering to the makings of warfare. Eventually, his cartoons encompassed pests and pestilences, smut and muck, and gross implements of armed conflict that traversed enemies at home and abroad. The result, however, was not an image of a tainted Americanism; instead, it was a picture of the disease of war, with caricature as the means of making national deficiencies in character more proximate and unnerving. It began with a move from birds to bugs.

Dr. Seuss was, in many ways, a product of his times even though he was regularly seen as something of a weirdo. A cartoon that appeared in the March 1945 issue of Leatherneck—a Marine Corps magazine—advertised a “serious outbreak” of a “lice epidemic.” More than mere scuttlebutt, the scourge could be traced back to December 7, 1941, the start of Marine Corps training for “the gigantic task of extermination.” The lice had unique, identifiable characteristics: slim and slanted eyes, two large front teeth that jutted out of its wide mouth, what might have been a star of the American Legion on its forehead, six spider-like legs with claws, and a tail with a Rising Sun on the tip. Its binomen was Louseous Japanicas, or the Japanese Louse. Dr. Seuss was part of a larger practice of “pseudospecies-making,”46 with crude animal-human hybrids as syllogisms for classifying and categorizing bodies politic. But this was not entirely a matter of visual metaphor as war allegory. The infamous Unit 731 of the Japanese army “disseminated plague-infected fleas on the Chinese people” as part of its invasion of the Republic of China.47 Here, insects were literal weapons in an instance of “entomological warfare.” The renovation of this concept into a species of rhetorical combat also has roots in the fact that the insecticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT, was discovered in 1939 during the production of explosives in Switzerland. A contact chemical, it was described by Rachel Carson as an “elixir of death,” because “one of its first uses was the wartime dusting of many thousands of soldiers, refugees, and prisoners, to combat lice.”48 DDT killed bugs. It was only later that the insecticide was found to have deleterious effects on humans. By 1944, Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service William N. Porter expressed his intent to poison German and Japanese troops with the same principles by which one could poison insects.49 For Dr. Seuss, this translated into the idea that Americans could, and should, take on the rhetorical character of exterminators.

Recall that Dr. Seuss was once the leading illustrator for the insecticide Flit. So when a cartoon appeared in PM on December 19, 1941, showing Sam-Bird aiming a manual spray pump filled with the pesticide of US Defense Bonds and Stamps at demonic mosquitos, the association was clear (fig. 15). In the cartoon, two bugs are noticeably larger than Sam-Bird, and each has a long nose that ends in a sharp stinger. One wears an iconic Hitler moustache and a massive swastika on its body. The other is a “Jap.” Beside them is another bug, also descending upon Sam-Bird. In the bottom left corner of the frame is the catchphrase, “Quick, Henry, THE FLIT!” In calling for civic action in the form of financial support, the cartoon shifts the valence from public opinion to support for war efforts. It even has crossover with an earlier ad that shows three American soldiers in a tank looking on in horror as a blood-red mosquito dive bombs them from the sky. In the ad, potential buyers are told that it does not cost much to kill flies and mosquitos. Citizens of war, however, were reminded that talk is cheap.

FIG. 15 Dr. Seuss, “Quick, Henry, THE FLIT!,” December 19, 1941. Dr. Seuss Political Cartoons. Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego Library.

This wartime idea of “Japs” as “yellow vermin” extends beyond insect imagery and into more encompassing concepts of pests as contagions as well as objects of contempt. For Dr. Seuss, it also goads the more explicit incorporation of cats in dealings with the double meanings and alterities of Self. On December 10, 1941, Dr. Seuss showed Sam-Bird under assault by a throng of alley cats. Sam-Bird sits at the end of “Jap Alley,” clutching a wooden plank rigged with a nail and strangling one of the feral cats. A swarm of alley cats approaches him. The cultural and characterological foreignness is arrant, with the Japanese pictured as resistant to human socialization, homeless, and stray. They are pests. The cats, like insects, are vermin. A couple months later, Dr. Seuss transmuted the visual metaphor of a swarm into the image of American “Japs” as the “Honorable 5th Column.” The cartoon shows a Japanese man as a roadside vendor in an outbuilding situated at the end of an endless drove of Japanese Americans that is making its way from Washington through Oregon to California. As they pass, members of the horde collect a box of TNT. All the while, another Japanese American man stands on top of the hut, holding a telescope pointed to the Far East, “Waiting for the Signal From Home. . . .” The image telescopes the comicality of the Other as a contact point for ascertaining the call to national character. In the same vein, it is a distillation of what was popularly known as the “yellow peril,” and so rationalizes the racism and fears of enemies within that led to Japanese internment. Dr. Seuss’s response to the disease of armed conflict is therefore the dis-ease of Americanism.

Herein lies a critical ambivalence in Dr. Seuss’s war artwork. His caricatures are unapologetically nativist, ethnocentric, and even racist in their merger of Japanese aggressors with Japanese Americans. Combining the two perpetuates the insect narrative and visualizes racial distinctions that are built on value judgments of “the Oriental” as “a discrete specimen of something resembling (but never attaining the status of) a normal—that is, Western and white—human being.”50 The “Jap” is at once the infester and the infested. This is not the place to rehash Edward Said’s foundational view of Orientalism (or its hang-ups). But World War II, like so many other wars, was described as a clash of civilizations—of cultures. This clash pitted “the West (which is rational, developed, humane, superior)” against “the Orient (which is aberrant, undeveloped, inferior).”51 In one sense, there arrives here a “Depression-era xenophobia” that refurbishes the Chinese Exclusion Act and a sort of “blood-will-tell racism” against model enemies.52 In another, there comes a need for visual assurance that orientalist rhetorics never just describe manners or customs but also deign to depict realities.53 Caricature is so compelling a visual rhetoric because it so often seems to capture what is actually the case, right there on the surface, right before our eyes. This is the feint of humor in a Deleuzian sense: it is a profound art of taking the superficial seriously. Caricature also distorts and deforms and deranges and draws together strange couplings. In doing so, it makes perceived realities even more exacting. Caricature, in this case, reroutes combat treacheries into jingoistic travesties. The ambivalence lies in the domestication of warfare as a comic abstraction of Self and Other. So it is that Dr. Seuss reveals insecticide as a remedy for specifically American mindsets in a wartime context.54

In this ambivalence is where the castigations of Dr. Seuss’s racism and nativism break down. After all, Dr. Seuss saw the possibility of a human family in the foundational principles of the American idea. Consider a cartoon from June 11, 1942, which displays Uncle Sam wielding an insecticide pump loaded with toxins for killing off the “Racial Prejudice Bug.” Uncle Sam smirks in the foreground, treating a white American man by spraying the insecticide into a funnel that is set up to blast its remedy in one ear of its patients and out the other. “Gracious!” says one man receiving treatment. “Was that in my head?” Beside him in a cloud of off-gas is a tiny bug. Behind him is a line of white American men, quite similar to the earlier horde of Japanese Americans, waiting to be treated. And above them all is the caption: “What This Country Needs Is a Good Mental Insecticide.” The reference here is decidedly not to prejudices against Japanese Americans, but rather to the racialized politics that prevented integrated US army units, discriminated against Black Americans in the war industries, and established a separate but equal public policy of military (and civic) sacrifice. Dr. Seuss’s point is that “real” Americans do not discriminate against their own, no matter the color or creed. Where this logic crumbles is in the very definition of what constitutes a Real American, as when Dr. Seuss expands on insect imagery to depict persons, groups of people, and values as embodiments of the filth and ordure of a war culture out of whack.

If the “fifth column” typified a foreign enemy, the “sixth column” was the enemy within. The sixth column constituted a collection of individuals that supported subversive activities by propagating the party lines of wartime adversaries. Or, in journalist and media critic George Seldes’s terms, it entailed any and all of those “using the means of communication . . . to spread dissension, disunity, fear, and suspicion.”55 For Dr. Seuss, it was the appeasers, the Nazi sympathizers, and even the obstructionist politicians who embodied the homegrown uglies of the Second World War. One specific target was the Dies Committee, set up in 1938 by Martin Dies Jr. via the House Committee Investigating Un-American Activities. Organized around suspicions of potential subversives, the committee promised to uphold “true Americanism.” Dr. Seuss echoed the widespread critique of the committee as un-American, in large part due to its association of New Deal idealists with Communists and its support of Southern congressmen who detested the Roosevelt administration and its policies. In a cartoon from August 1942, Dr. Seuss recalibrates his insect imagery to suggest how an anti-American contagion had infected certain portions of the US body politic.

Standing before a small crowd of “Just Plain Bugs” is a larger, more grotesque insect. It has a long, lanky body with an oddly ribbed and furred thorax. Its antennas are crooked and bent over its head. Its nose is bladed and sharp. It has a curvilinear tail that comes to a point with a tuft of fur at the end. The appendages of its back limbs are clasped together, and one front limb supports its upper body while the other gestures to the group. With eyes closed, head high, and mouth open, the insect boasts: “I don’t like to brag, boys . . . but when I bit Col. McCormick it established the greatest all-time itch on record!” The itch was an anti-Roosevelt itch, delivered by “The Anti-Roosevelt Bug.” It refers to the contaminated politics of publisher Robert R. McCormick, a target who received the comic wrath of Dr. Seuss like Lindbergh before him. McCormick ran the Chicago Tribune, which was well known for calling Roosevelt a Communist and lambasting the New Deal. Along with his cousin, Eleanor M. “Cissy” Patterson, who oversaw the Washington Times-Herald, McCormick used his newspaper to decry anything and everything east of the Mississippi River, thinking Washington—and no doubt other East Coast cities—“a Sodom and Gomorrah of sin.”56 As a result, Roosevelt took advantage of many opportunities to dub Cissy a subversive and to refer disparagingly to “the McCormick-Patterson Axis.” This forms the basis of Dr. Seuss’s alignment of Axis ambitions with the disease-carrying characteristics of mosquitos and germs and the general filth of Japanese imperialism and Nazi propaganda. These alignments were later characterized as “Stalin-itch,” “Hitler-itis,” “Fascist Fever,” and the like, all to the end of seeing comic ugliness in those who were awash with the Ugly Spirit of Americanism.

Take another cartoon, wherein a man representing the AFC sits in an “old Family bath tub” (signifying the “American Hemisphere”) overrun by ghastly creatures. The AFC man bathes himself in filth with eyes closed and a smile on his face. Sharing his bath is an anthropomorphic alligator, a menacing (albeit tiny) shark, an octopus, and a cockroach-like insect, all emblazoned with Nazi swastikas. Filth, effluence, and infection overlap in this image and portray an impurification of the very structure of American national character that is punctuated by the claw feet on the legs of the tub. Such impurification is mapped onto the “Jap” stereotype when, in September 1941, Dr. Seuss shows a familiar Japanese character lowering himself into a steaming bath that has been drawn in a clawfoot bathtub. The water resembles sludge and boils over as “War With U.S.” Next to the “Jap’s” head is an “Old Japanese Proverb” that perverts a foreign tongue: “Man who draw his bath too hot, sit down in same velly slow.” Instructively, the man is trying to cool himself with a Japanese hand fan, traditionally a feminine accoutrement that also comes off as an allusion to folkloric devices of ancient East Asian combat. The plain truth that Dr. Seuss travesties is that World War II posed a biotic threat with the capacity to cause US citizens to bathe themselves in the same pollution as “the Japanese character,”57 and then again to embody the very filth whose surface fetidness betrayed an even deeper evil. Joe Public gone bad, in other words, is just as corrupted as a Jap. Surface meets depth. Good blends with bad. The American Self becomes the Ugly Other. The humor comes from these mergers that indulge even as they inveigh a sorry view of US national character in the comic looking glass.

Dr. Seuss was probably most perturbed by the notion that America had become a citizenry of “cheerful idiots,” to use a phrase from Roosevelt. US citizens seemed to lack a capacity to recognize the fragility of its political, cultural, national, and now international experiment, which could not be kept safe on a wing and a prayer. As such, Dr. Seuss rounded out his caricatures of national character with machines to depict the proper operation of war and to visualize how the United States could understand itself as an operative democratic nation. A few images in particular get at these tensions. The first was published on February 18, 1942. Its message is ironically antidemocratic insofar as it continues Dr. Seuss’s sense that U.S. entry in the war meant that the time to stop deliberating had come. In the cartoon, Uncle Sam works a strange contraption that is supposed to be a weapon of war (fig. 16). The “Big Bertha” is something of an American howitzer, only much less a mortar than a mucked-up machine clogged and bunged by “political squabbles,” “just plain gas” (the machine’s exhaust), “blunders,” “complacency,” “red tape,” and “carelessness.” This cartoon encapsulates a network of ideas that Dr. Seuss put to work in imaginative portrayals of American incompetence in the conduct of both politics and war. It foregrounds Dr. Seuss’s sense that armed conflict indicated the vices embedded in the American Way. The “Big Bertha” is equipped with multiple cannons, all of which fire munitions in a variety of disconnected directions, the most telling of which is the gas from political squabbles that blows back in Uncle Sam’s face. In direct equipoise is a “pip” that is fired from the canon “for Hitler and the Japs,” intimating the military and political pittance for American firepower.

FIG. 16 Dr. Seuss, “Our Big Bertha,” February 18, 1942. Dr. Seuss Political Cartoons. Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego Library.

The politics of war are just as important as the cultural politics resident in this image. In his pull for war production, Dr. Seuss also amplified the racialization of the factory floor, specifically as it disrupted the sort of harmony needed for a nation to succeed in armed conflict. In April 1942, Dr. Seuss took on the common practice of industrialists denying Black workers either an opportunity to work or equal treatment based on “stereotyped views of their alleged laziness, lack of mechanical ability, and unreliability.”58 The cartoon depicts a “Discriminating Employer” clutching an American flag and driving a tank with two men—one representing “Negro Labor” and the other “Jewish” labor—being towed along in tiny carts. The employer proclaims: “I’ll run Democracy’s War. You stay In your Jim Crow Tanks!” Dr. Seuss’s travesty of labor shortages and the “scab race” of industry is unabashed in the depravity of white workers deeming dislikable factions of the workforce inadequate. As important is Dr. Seuss’s alignment of race relations and the democratic exigencies of warfare. To sink to the depths of Us–Them relations at home was to feed the beast of Us–Them rhetorics abroad. Racism, like isolationism, hampered the war efforts and corrupted American democracy. New Deal politics offered an ideological anchor for appeals to integration, economic opportunity, and social equality. Organizations like the American Federation of Labor, with its commitment to isolationism, therefore conflicted with the Congress of Industrial Organizations and its history of progressive racial politics, betraying a politics shared by Dr. Seuss and others who declared that to be anti-labor was to be antiwar—and to be antiwar was to be un-American. Isolationist industry leaders tried to avoid alignments with the nation-state and so took little “action to rein in the racist and antidemocratic attitudes and policies of . . . member unions.”59 Dr. Seuss made war a matter of public interest by illustrating labor unionism as important for a united front, complete with equal opportunity and racial justice, to make any aspect of national character based on prewar prejudices antiquated, outmoded, and ultimately unworkable. As he expressed in another cartoon, race prejudice in the United States was akin to “The Guy Who Makes a Mock of Democracy.” Such mockery is, for Dr. Seuss, the worst of “wartime blunders.”60

Given all this, though, Dr. Seuss’s rhetorical judgments of wartime national character emerge more subtly, and come full circle, in the image of a small cat. Hammering home the notion that animal imagery amplifies the nature of human conduct, a cat appears in many of the cartoons that specifically target civic engagements with war. In the prewar period, the cat emerged in moments of dismay as he did in May 1941 when he and an American citizen shared in the shock of seeing a woman, representing Fraulein Bund (a German American Federation and organization for American Nazis), pushing a baby carriage with an infantile progeny, the AFC. Toward the end of Dr. Seuss’s caricature campaign, the cat adopted the dirty looks of unfit US citizens. The cat is in the bottom right corner of the cartoon showing Uncle Sam cure Americans with a “Good Mental Insecticide.” What we find in the cat, then, is “a character without a fixed center,” and maybe even “a con artist, a trickster, a character of possibility, aggressively adaptable to the occasion.”61 The cat is sometimes the provocateur, as in Dr. Seuss’s depiction of Jap Alley. Sometimes the cat is the cudgel. Consistently, the cat (and catlike comicality) carries the rhetorical load of reorganized principles for sociopolitical communion in perspectives on the American Way that are prodded by the exigencies of war. Following Dr. Seuss, fantastical reimaginations of national characteristics reinscribe matters of wartime civic duty when it comes to the cultural politics of laughing at, laughing off, or laughing last.

Conclusion: Oh, the People We Be

Caricature is a rhetorical art of comic characterization. As a mode of humor, it is also an art of visualizing consequences of character so that in their comic guise they might be seen for the laughingstock that their subjects and objects of ridicule could become once, say, a war has come and gone. The last of Dr. Seuss’s wartime cartoons is instructive in this regard (fig. 17). It appeared on January 5, 1943, just two days before he enlisted in the Information and Education Division of the US Army. Dr. Seuss had earned a commission to “Fort Fox,” the film production studio of Frank Capra’s signal corps unit. There, he worked on propaganda films for both citizens and soldiers until his discharge just over two years later. Dr. Seuss’s last cartoon caps off his caricature campaign against those citizens who typified an American nation out of character.

FIG. 17 Dr. Seuss, “The Veteran Recalls the Battle of 1943,” January 5, 1943. Dr. Seuss Political Cartoons. Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego Library.