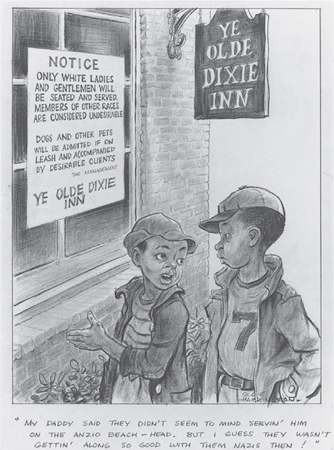

FIG. 18 Oliver W. Harrington, “My daddy said they didn’t seem to mind servin’ him on the Anzio beach-head,” 1960. From Dark Laughter, April 2, 1960. Courtesy of The Library of Congress. Used with permission of Dr. Helma Harrington, Berlin.

Children of War in Ollie Harrington’s Dark Comedy

There is a well-known trickster in African folklore. He is Anansi, the Spider, known as a shapeshifting figure for the Good and Bad spirit in structures of cultural knowledge. Anansi originated in the folktales of the Ashanti of West Africa but eventually cropped up in US American slave narratives. Anansi is cunning. He is clever. He is an embodiment of acumen and its attendant conceits. There is an Anansi parable, however, that demonstrates the trickster out of humor.1

Anansi is trying to bottle up all the knowledge in the world and hide it away at the top of a large, bristly tree. He puts the knowledge in a big pot, straps it to his front, and attempts to climb. But the pot prevents him from keeping a good grip on the bark and branches. Anansi slips. He falls. He gets frustrated. Then, from the ground below him, laughter billows up. The laughter comes from his son, Ntikuma. “Tie the pot behind you,” says Ntikuma, as if telling a joke. “That way you’ll be able to hold onto the tree.” Annoyed that his child was right, Anansi fumed and fussed and accidentally dropped the pot. Knowledge spilled out and got swept up in a wind that took it out to sea, dispersing it throughout the world. Humbled on the walk home, and sufficiently humored by his experience, Anansi expressed to Ntikuma, “What is the use of all that wisdom if a young child still needs to put you right?”

In the 1920s, cartoonist Oliver (“Ollie”) Wendell Harrington suffered his own experience with the strange fruit of what Jonathan Scott Holloway might call “Jim Crow Wisdom.” The adult who bore it was neither trickster nor parent. But she was bigheaded in her bigoted character. “Never, never forget these two belong in that there trashbasket,” said Miss McCoy, the sixth-grade teacher of Ollie Harrington and his friend, Prince Anderson. Ollie and Prince were the only two Black students in their class within a South Bronx schoolhouse. It was a few years after the Great War and four decades before Lyndon B. Johnson’s dream of a Great Society, haunted as it was by the specter of an Ugly America. As Harrington tells it, Miss McCoy embodied the sort of unabashed racism and nativism that less than twenty years earlier had yielded an exhibit at the Bronx Zoo that featured Ota Benga, a Congolese pygmy who was kept in a cage with his “fellow” monkeys. Harrington’s peers reeled “in peals of laughter” at Miss McCoy’s comments.2 Harrington turned to the spirit of Ntikuma.

Ollie took to drawing caricatures of Miss McCoy in the margins of his notebook. One shows Miss McCoy “being rammed into a local butcher shop meat grinding apparatus.”3 Another pictures her simply as the bust of an old maid with a drooping face and woolly-minded eyes. These and other caricatures represent something of a distorted mirror stage in Harrington’s development as a cartoon artist. They formed the groundwork for his lifelong portrayal of adult idiocies as they are manifest in “the ordinary problems of ordinary Negroes and the ironic aspects of Negro-white relations.”4 It was Harrington’s caricatures of everyday conflicts in race relations that led Langston Hughes to dub him “Negro America’s favorite cartoonist.”5 Miss McCoy seemed to have a formative impact on Harrington’s caricatures of Black culture throughout the Cold War era, many of which situated children not as audiences or passive victims of race hatred but rather as rhetorical agents in its deconstruction. Many, too, brought the specter of cultural warfare to bear on matters of armed conflict.

Born on Valentine’s Day in 1912, Ollie Harrington grew up into nearly a century of war that traversed Jim Crow culture through the Second World War to the Resistance War Against America and the civil rights movement. By 1932, he was on assignment with the Amsterdam News in New York. It was in this rag in 1935 that Harrington’s most famous character, Bootsie, first appeared in a soon-to-be serial strip, Dark Laughter. Much scholarly attention to Harrington dwells on Bootsie, as well as his war correspondence for the Pittsburgh Courier and cartoon politics that endured through his own self-exile in 1951 amid McCarthyism and Cold War hysteria. Bootsie is still considered the first nationally recognized Black cartoon character in the United States. A primary reason is that he was “a black everyman of Harlem, an urban dweller who had come to the city during the Black migration and brought with him his southern ways.”6 As such, so-called dark laughter was invoked by “the realistic feel of experienced urban life” that Bootsie embodied. Harrington described this experience as the “almost unbelievable but hilarious chaos” ensnaring and encircling Black culture.7 In emphasizing the general politics of Bootsie, examinations that mostly skip over Harrington’s caricatures from the 1960s miss some opportunities to understand national character with regard to an important gauge of Black experience: children. Put more plainly, there is a need to understand the whiteness of wartime American national character through the childlike, corrective attitude that can emerge out of caricatures that put Blackness at the center of cultural politics. Folktales offer moral judgments comprehensible by children. Relatedly, children can offer “folk” judgments on the casualties of war and the adults who cause them. As in Dr. Seuss’s work, caricatures in Ollie Harrington’s cartoons constitute a sort of childlike wisdom that speaks volumes about adult worlds. Unlike Dr. Seuss, though, Harrington employs the rhetorical force of children as caricatures in order to imbue the folly of war and war culture with a sense of humor. This chapter contends that Harrington’s caricatures of Black children across the Cold War era demonstrate the damage done by systemic racial prejudice at home and the possibility that visual humor presents real rhetorical agency in the midst of broader crises in national character.

Harrington’s caricatures fit in “a tradition of wartime cartoon characters.”8 In the broad history involving cultural politics of caricaturing racial and racialized bodies, Harrington’s comic artwork fits in as a contravention to what Rebecca Wanzo calls “visual imperialism,” or “the production and circulation of racist images that are tools in justifying colonialism and other state-based discrimination.”9 To be sure, it fits within a complicated historical march of visualizations for “real” Americanism that includes imagery by popular cartoonists like Larry Dunst, Herbert Lock (or “Herblock”), Bill Mauldin, Robert Osborn, Edward Sorel, and even James Montgomery Flagg. An important distinction is that Harrington did not focus on depictions of political figures and members of the establishment class (i.e., presidents and opinion leaders) or readily recognizable abstractions of American-ness (i.e., Columbia or Uncle Sam). Nor did he follow a tendency of Black cartoonists to caricature Southern whites in a form of retributive justice.10 Instead, Harrington lampooned the links between combat mentalities among those with small-minded, racist attitudes and US war culture. Black children stood in for and reflected ongoing struggles to fend off the otherwise permanent plights of institutional racism and systemic inequality. In other words, Harrington’s children of war challenge democratic principles and policies as executors of basic needs like food, shelter, life, and liberty. Harrington’s children were not caricatures of dissent from war. Nor were they “beautiful” portrayals of Blackness, particularly given their drift into the “ugly” and the “offensive” as rhetorical forces for “antiracist protest.”11 Rather, they were travesties of domestic discord, amplifying a minority court of public opinion about racialism as the site of homegrown friend-enemy conceptions of US Americanism and American exceptionalism. They constituted a comic tyranny of caricature, working against what Wanzo rightly sees as an imperialism of the very visual field of Blackness (and Whiteness) that “can make everyday lived experience a racial grotesque,” then as now.12 In Harrington’s comic travesties is an affirmative, powerful revisionist history of this imperialist bent in the tradition of wartime caricatures.

Childlike humor has long been associated with notions that a child is brutally honest. Children say the damnedest things. They express observations that are sometimes improper, impolite, incomprehensible, or downright rude. Their observations often reflect our unstated assumptions about the world back to us. They exaggerate what we take for granted. They uncover what we conceal in our deepest held, even if superficial, beliefs. Psychoanalytic fidelities notwithstanding, Sigmund Freud once saw in children the faculty for expressing what he called “earnest conclusions” based on “uncorrected knowledge.”13 As a form of humor, such a childlike faculty allows for the correction of perspectives through the “misuse of words, a bit of nonsense, or an obscenity.”14 The humor of Black children facilitates Harrington’s construction of homo rhetoricus liberi out of homo rhetoricus Africanus,15 born as this figure is out of the witlessness of adults.

To set up the comicality in Harrington’s children of war, this chapter begins with a brief outline of Cold War public culture. Included in this outline is a recognition of the very real, very disturbing problems of lynching, rampant unemployment (despite the war boom), unshakable Jim Crow politicking on issues of social policy, housing inequities, and other exigencies that led many to see the close of the “Good War” as a good time for a “Second Reconstruction.” The Cold War context of panic, blacklists, and investigations is also accounted for. Calls for civil rights in this context were chalked up to Communist ploys that inspired factions of white Americans to take up a “massive resistance.” Some believe that the Vietnam War supplanted the purpose and progress of civil rights. At the very least, a national culture of—and at—war exacerbated the tensions between containment and liberation, separation and excision, whiteness and Blackness. Harrington’s children were caught in the middle, especially since “integration” had become a contemptible word to congressional Dixiecrats. If Bootsie embodied Black experience, Harrington’s children of war became its unlikely reflections in the comic looking glass. Through an examination of Harrington’s caricatures of Black children in the Pittsburgh Courier (and the Daily Worker, in 1967 renamed the Daily World) primarily between 1961 and 1975, I argue that Harrington laughed at the racial character of a US nation that persisted to draw battle lines as color lines, and vice versa.

Old Stories, New Wars

To revise an old Vietnam War era saying: Children without a chance for peace are like a home without a roof. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was not known for his progressive views on race relations. He fumbled implementation of the Brown v. Board of Education decision and even sympathized with the interest among Southerners to keep white and Black cultures separate. Still, Ike was an incrementalist who might have been wary about placing the burden of desegregation on children. He was also an outspoken critic of the folly of war, even though he justified its use in the name of preserving the forces of Good over Evil. In a speech before the American Society of Newspaper Editors in April 1953, Ike ruminated on the chance for peace, urging that every war effort “signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed,” and most upsettingly those who place the heart of humanity in “the hopes of children.”16 This sentiment rings truer for Black children of war.

On April 2, 1960, Ollie Harrington published a cartoon in the Pittsburgh Courier that provided a Janus-faced view of the Cold War era (fig. 18). Two Black boys stand outside a Southern establishment. A large sign in a window reads: “NOTICE: Only white ladies and gentlemen will be seated and served. Members of other races are considered undesirable.” Perhaps worse is the welcome extended to leashed animals, but only those “accompanied by desirable clients.” One of the boys stares blankly toward the sign while his friend reflects, “My daddy said they didn’t seem to mind servin’ him on the Anzio Beach-head. But I guess they wasn’t gettin’ along so good with them Nazis then!” The boy’s puerility is as palpable as his petulance.

FIG. 18 Oliver W. Harrington, “My daddy said they didn’t seem to mind servin’ him on the Anzio beach-head,” 1960. From Dark Laughter, April 2, 1960. Courtesy of The Library of Congress. Used with permission of Dr. Helma Harrington, Berlin.

The cartoon recollects notions of a “New Negro” that emerged at the close of World War II. This notion is disappointed by overt racism and policed segregation that, even if formally ended in the military in 1948, persisted in the most basic institutions of US public culture. Just imagine that the first question asked of Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas at a press conference when he visited India in 1950 was: “Why does America tolerate the lynching of Negroes?”17 This question eventually became a Russian catchphrase for calling out moral hypocrisies and deflecting its own human rights abuses, but it nevertheless encapsulates the dirty laundry in postwar airings of an America that remained racially unwashed and morally unfree. Harrington’s cartoon also displays the deep surfaces of a cold culture war that rendered “undesirables” both foreign enemies and domestic contenders for equality in free thought, speech, and action, while simultaneously alluding to the international attitudes of disgust that impacted US political alliances at home and abroad. The Civil Rights Act of 1960 was enacted a month after publication of this cartoon. Yet the next four years saw some of the most decisive activities in the cultural landscape: anti-segregation sit-ins, Freedom Rides, the Albany Movement, the use of US marshals to integrate Ole Miss, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and so on through to another civil rights act. Legislation begat cultural lag, and discriminations continued to run rampant in school systems, labor economies, and housing markets. What is more, another war was afoot. The conflict in Vietnam mirrored a form of homespun militancy that, for many Black citizens and soldiers alike, sparked another two-war front (or, a two-front war) that put the racialism of the American Way in the crosshairs.

There is a deep and complicated history to this ambivalence of US warism. The idea that there could be a federal pronouncement of good civic standing underwrote so many nationalistic efforts during World War II and the corrective measures taken to manage public opinion. This led to the postwar “tensions project” (1949–53), sponsored by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which yielded insights on “aggressive nationalism” and threats to peace. Indeed, what Margaret Mead acknowledged as the “psychological equipment” for winning the war was recognized by UNESCO as the predispositional baggage of national stereotypes, and it facilitated Cold War mentalities as the makings of more generalized conceptions of war as a necessary good when it comes to an all-out defense of US Americanism. The shadows cast by these dark days are long, blending into a nationalistic hubris that fomented the Vietnam War and produced a perverted, top-down, and predacious warrior ethos we now see encircling the War on Terror. Harrington’s work pronounces his attention to the impacts of both war footings and culture war orientations. The dark laughter in Harrington’s caricatures amounts to a gloomy look at the failures of American democracy in an incapacity to protect all citizens at home even as the United States waged war with international Others deemed a threat to homespun life and liberty. His comic judgment is even weightier given that Harrington’s view was that of an outsider looking in—of a citizen unwelcome in his home country.

There is every reason to see the physical and symbolic violence against nonwhite citizens at home as a perverse reflection of the carnage afflicted on nonwhites elsewhere. It is fair to align the racialism driving much warfare with the racism that defines Black–white tensions in the late 1940s and beyond, and thereby to approach the Black children in Harrington’s cartoons as caricatures of a US war culture in particular riven by old stories of race relations rewritten for new times. In many ways, these children typify the “struggles for national and racial equality” that “characterize the entire Cold War era.”18 Particularly in the abovementioned cartoon, the two Black children capture confrontations between institutions of racism and everyday rituals of prejudice, thereby reiterating something as banal as the contrast between a racial dialect and the racialized conceit of the faux English pride in Deep Southern values. Consider the vernacular phonology in the child’s speech versus the archaism in the sign outside “Ye Olde Dixie Inn.” Such is an emblem of “old ways” and “old attitudes” that the Black press and civil rights activists aimed to combat.19 Harrington waged a battle over national character through caricatures that positioned Black children as the most critical and perspicacious—and indeed humorous—observers of “the ridiculous side of American race relations.”20 This darkly comic side is driven by false premises and false promises in the democratic experiment.

Here again lurks a complicated history. Metaphors and movements around a “New Negro” date back to the Harlem Renaissance. Following the so-called “Father of the Harlem Renaissance,” Alain LeRoy Locke, a sense of “newness” signified a cultural reset around the tensions that had long been connected to mattes of racial pride and prejudice, not to mention expressions of Black selfhood and self-presentation. From Frederick Douglass and Phillis Wheatley through W. E. B. Du Bois and to the numerous and prominent Black writers, intellectuals, and artists in Harrington’s day, one can locate in discourses of the “New Negro” not simply a “rebellion against what has been, but opportunity for what may be.”21 World War II hardly redeemed democracy. Nor did it serve as a racial equalizer. Black citizens were held in limbo as second-class citizens following a relative failure of the Double V campaign. As Mary L. Dudziak argues, a recurrence of troubled race relations—made even more pronounced in times of war—spoils “the image of American democracy.”22 Or, in Du Bois’s words, it magnifies the ways that a nation reels and staggers, makes mistakes, and commits wrongs as it attempts to sustain the great and beautiful aura of egalitarianism. Any ideal of democracy in the United States, though, was always already sullied by the institution of slavery, and thereafter the perpetuation of race hatred in the horrible, and horribly festive, act of lynching. In fact, it is the very principle of racism as a mundane way of thinking, speaking, and acting that makes it more of a burden on national character than its manifestation as a pathological monstrosity.23 Hence the Second World War was fought on two fronts, with racial politics at home and the cultural politics of Americanism at stake in so many military excursions overseas.

The fogs of iron curtains and color lines figure prominently here. An indubitable dilemma in the postwar United States was that commies were cast with much the same die as “colored people” insofar as containment rhetorics situated Americanism “within narrow boundaries of permissible thought and behavior.”24 The motivations for such boundaries were not entirely unfounded. There were, after all, justifiable concerns that the prospect of “Soviet tyranny” looked a lot like the perversions of “Nazi totalitarianism.”25 Yet concerns about the rise of communism in America provoked oversimplified reactions to the “Negro Problem,” which by the early 1950s appeared as an extension of ye olde world and a new world reordering averse to anything like Black Reconstruction. The push for civil rights came off as a Communistic ploy. The preservation of US American national character got couched in homogeneous images of collective selfhood.

At the nexus of these rhetorical attempts at containment were matters of Black action in the civil rights movement, iterations of white resistance made grotesquely manifest by an ethos of the Southern Manifesto, and pervasive fears about the Red Menace. Following World War II, there was a popular dispersal of “the delusion that the nation was being overrun by communists” in film, on television, and in print.26 This was bolstered by anti-Communist national security reports like NSC-68 as well as President Harry S. Truman’s “Campaign of Truth,” which began in 1950 as a psychological “war of words” in counteraction to Soviet propaganda and in support of postwar sentiments of nationalistic solidarity.27 One particular concern was that Blacks in uniform had given way to domestic militancy among Black citizens.28 Black militancy put federal and local governments in a precarious position of needing to deconstruct a system of racial trauma, inequity, and injustice. It pressured ordinary citizens, too, to think hard about what kind of a democratic people the United States should be if the principles of American democracy would be definitive characteristics of a free and equal nation not compromised by the follies of war.

As it was, embattlements regarding national character became outgrowths of “old hatreds.”29 The federal government was burdened with the task of codifying a “Great Society” that was implied by, and finally promoted after, victory in the Good War. The military-industrial complex was transformed into a military-cultural complex, which was judged by its successes and failures in nationalistic efforts to secure equal opportunities for all people. The evolution of the Cold War into the Vietnam War, however, all but ensured “the dwindling of official attention to civil rights matters.”30 President Richard Nixon turned away from the civil rights movement. Harrington’s modus operandi was to animate “the foibles, the misapprehensions, and the predicaments of African Americans” as they devolved from the 1950s through the 1970s.31 This devolution revolved around “the treatment of black soldiers, segregation, and lynching.”32 The fallout from war, for Harrington, was most evident in false promises around that olden creed about liberty and justice for all, as evidenced by the inefficacy of the G.I. Bill for Black veterans, the continuation of segregationist policies, and targeted racial terror throughout the American South. The droll humor in Bootsie cartoons took on issues of police brutality, antiwar activism, the rise of Black power and Black Nationalism, and the prominence of militant groups like the Black Panthers. Moreover, Harrington pictured Black Americans as rhetorically and materially oppressed by a nation that was more apt to look upon itself in Black-and-white terms rather than for its true colors. Such oppression emphasized a through line from the Red Summer to a Red Scare mentality that urged fears about Black empowerment and a disempowered white America.

Along with communist disquietude, the Cold War era made it so that domestic civil rights were aligned with more international and anti-colonialist movements. For instance, organizations like the Council on African Affairs (which allied with the American Communist Party before its disbandment in 1955) contributed to Pan-African responses to generalized cruelty of whites against Blacks by linking “the struggles of African Americans against Jim Crow” to “the struggles of Africans and colonized peoples for independence.”33 This led to a worldwide ideological union of Black cultures. Another part of this story is the Black press. Following P. L. Prattis, editor for the Chicago Defender and later the Pittsburgh Courier, the Black press was “an instrument of the embattled minority in action against the repressive majority,” as well as a medium for “telling the people the truth, regardless of the corrosive effect.”34 The Black press also “often made common cause with the American Left and, at key moments, with the international Left, including the Communist Party.”35 Especially in the early years of the Cold War, editors of Black newspapers were regularly accused of being in cahoots with Communist radicals and threatened by the economic fallout from publishing subversive content since advertisers were cautious in associating their products or services with anything that could be characterized as extremist. Still, the Black press was a prime source for people of color to track “the changing sense of self, community, and country.”36 The Black press is a voice and vision for characteristics of Black culture.

The Pittsburgh Courier in particular is integral to the Black press. It was not only among the most popular Black papers during and after World War II (once the leading Black weekly in the United States before being acquired by the Defender in 1966). The Pittsburgh Courier was also considered “a maverick press” in the fight for racial justice.37 James Baldwin called it “the best of the lot.”38 The paper rose to prominence following the Great Migration period. Robert Lee Vann, a successful Black lawyer, was its original editor and progenitor of its fundamental mission to secure the betterment of Black America. In a 1915 editorial, Vann promoted war as an opportunity for “THE NEGRO” to assume “HIS RIGHTFUL PLACE IN THE OPINIONS OF AMERICANS.”39 Prattis, who took over editorship during World War II after Vann’s death, used his editorship to propagate the “Double V Campaign.” The campaign advocated “victory over totalitarian forces overseas as well as over similar forces in the United States that were denying equality to blacks.”40 As Prattis noted, audiences and artists of the Pittsburgh Courier were drawn to “similes and metaphors that lay open the foe’s weaknesses,” and to “cutting irony, sarcasm and ridicule.”41 This appeal is significant for a consideration of Harrington’s work because the Pittsburgh Courier had a large section devoted to editorial cartoons and a readership primed for the sting of its biting humor.

The same could be said of the Daily World after switching back to being a weekend to a daily paper and then enlisting Harrington in 1968. The paper itself was a byproduct of the Communist Labor Party in 1919, which grew into the American Communist Party. In fact, the Daily Worker (later dubbed the Daily World) was the paper of the American Communist Party. In the 1930s and 40s, it organized around anti-lynching campaigns, the cultural front of the peace movement, and activism toward civil rights. This made it something of an ally to the Black press, especially considering that the Daily Worker evolved into an outlet for denouncing Jim Crow laws and reporting on the racist activities that tormented the Black community. Harrington and other cultural workers aligned themselves with the paper because it supported a more democratic form of Americanism. The Daily Worker shut down between 1958 and 1960 due to its embroilments in the Red Scare. However, when it resumed publication in 1968, it did so under the editorship of African American journalist John Pittman, a respected reporter and public supporter of the civil rights movement (including the Black Panthers). The Daily World therefore exceeded Bootsie’s somewhat parochial politics to delve into issues of class warfare, war profiteering, and the military-industrial complex as a cumulative cultural drain on Black families and their children.

In this context, it is unsurprising that from the early 1950s through the close of the Cold War, “seeing red” was often analogous to seeing black, which “weakened the legacy of civil liberties, impugned standards of tolerance and fair play, and tarnished the very image of a democracy.”42 More to the point, it privileged myopia as a way to win not only the war for US democratic principles but also the culture wars against those who sought to reorder the distribution of public goods. Problems from racial violence to rampant institutionalized prejudice enveloped the “character,” “temper,” and “cultural makeup” of communities that rendered the Vietnam War a sorry outcome of those Cold War boundaries that so colored public culture.43 For Harrington and others, critical commentary was better (even necessarily) conducted outside of US borders. After years of publishing cartoons, editorials, and news stories in the Pittsburgh Courier (which, incidentally, was monitored under the FBI’s “RACON” program), and because of his work with other papers like the People’s Voice and the Amsterdam News, Harrington came under fire.

Harrington’s cartoons exemplify the dark ugliness clouding un-Americanism. During World War II, he covered the Tuskegee Airmen from the “safety” of a C-47, combatting the postwar “retrenchment of racist values.”44 At one point he even reported on the activities of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). While reviving his cartoon campaigns through caricatures of the Black ghetto, Harrington served as a public relations director for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). As early as the 1940s, Harrington was linked to the radicalism of the Black Left and put on a watch list by the FBI, the CIA, and eventually the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). By the late 1950s, Harrington had become “persona non grata in his home country.”45 So he emigrated with some other African American writers, critics, commentators, and artists. During a stint in Paris, Harrington joined the likes of Chester Himes, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Nella Larsen, and Richard Wright. Later, following Wright’s controversial death in 1960, Harrington moved to East Berlin while some like James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Julian Mayfield, and others went to Ghana. Importantly, Harrington brought his own “Vietnam Syndrome” abroad, providing an “outsider’s” perspective on American warfare. Like so many in the community, Harrington feared the existential threat that Cold War America posed to Black culture, never mind his own life. He even mused with his brethren about “whether the integration of Blacks would transform and democratize the nation or whether Blacks would be remade in the image of a stultifying, inequitable, and morally bankrupt American society.”46 Self-exile thus developed into an “enabling condition” in that it “symbolized a broader tendency among Black Americans to view the political status and identity of African Americans through African liberation struggles.”47 Harrington remarks in an essay, “Why I Left America,” that his overarching goal was to advance Black Liberation.48 He kept up on happenings on his home front through US news reports,49 and American newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier, the Daily Worker (eventually the Daily World, and now the People’s World, an online newspaper), and the Chicago Defender (until 1963) became his organs for caricature. It is in the cartoons he published in these papers that Harrington’s emphasis on children of war took shape.

Children are the metaphors for, and the embodiments of, Harrington’s comic looking glass. To borrow a few words from a speech delivered by Ralph Ellison in September 1963, “these children” were some of the most discerning “living critics of their environment.”50 They were also quite moving sources of Black humor in caricature given their status as Outsiders of the Adult World who are nonetheless caught up in it. And they took on the subversive quality and critical distance that can empower an outsider to exploit the tensions between those on the outside and those looking in, but with the sort of proximate connection needed to create a distorted mirror image. The children in Harrington’s cartoons are vehicles for “caricaturing, challenging, and subverting adult values.”51 These values were the targets for Harrington’s revisions of the double binds and double standards that animate race and racism in US war cultures. Harrington’s children converse about the mistreatment of Black adults, reflect on policy measures around integration and social welfare, comment on the domestic fallout from warfare, and even wrestle with racial prejudice themselves. At no point are they innocent or ignorant. Instead, they are the unlikely foot soldiers of wartime appeals to a more realistic imagination of the racial impairments in US national character.

Comic Images of Blackness: An Interlude

Before turning to Harrington’s caricature campaign for children of war, a brief pause is needed to account for the importance of Black humor as a peculiar yet all too typical vehicle for breaking with traditional views of US Americanism. After all, as literary critic Harry Levin once put it, Black humor provokes reexaminations of rhetorical judgments because it “confronts us literally, as the power of Afro-American blackness asserts itself” in the very comicality of coming full circle amid specific zeitgeists.52 The very Blackness of Black humor can be found in the ambivalence of absence and presence, of rejoicing and mourning, that shows forth when traditions themselves are “shared, repeated, critiqued, and revised,” in vernacular as well as in visual imagery.53 Blackness exists “on both sides of the existential fence,” says Alain Badiou. “As mourning, it makes us cry; as humor, it makes us laugh. And it will make us laugh about mourning itself.”54 Harrington’s caricatures appeal to this comic ambivalence.

One thing to acknowledge first and foremost is that comic images of Blackness, and in particular Black Americans, are endemic to—nay, inveterate in—representations of white America, and by extension white citizenship. In the words of Jessie Fauset, Black people are repeatedly seen “as a living comic supplement” to images of whiteness.55 Or, following Wanzo, there is a rich tradition of Black artists deploying “racist caricatures to mark the citizenship of black subjects in order to show that it is marked—by an absence of rights or alienation from the nation.”56 This is why the so-called “Negro Life” was characterized in the early 1900s by some such as poet and writer William Stanley Braithwaite as “a shuttlecock between the two extremes of humor and pathos.”57 It was lightness and darkness. It was the fantastical and the all-too-real. It was freedom and unfreedom. It was, simply, a racial travesty typified by the New Negro as a sort of “comic disparity between the black man and his station.”58 Hence scholars like Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Gene Andrew Jarrett have probed representations of Blacks in the United States for the highest as well as the lowest forms of human life, for the best and the worst of true and false Americanism, for a sense of cultural celebration rather than despair, and thereby for an idea of “blackness as presence” rather than absence.59 Humor in the Black tradition betrays forms of rhetorical significance that do not require official realms of social acceptance and political enfranchisement. The history of “racial uplift” in Black humor relies on manipulations of imagery to the end of manipulating lived realities.60 In this manipulation is an image of Blackness laid bare in the comic looking glass.

There is in the humor that comes from such comicality a certain practice of making cultural assumptions about Americanism not necessarily the butts of jokes but most certainly the subject of a distorted perspective. For one thing, insofar as humor is an index of some national or collective character, the Black tradition of humor is a byproduct of the minority status forced upon African American communities for so long, never mind on Africanism. According to Mel Watkins, this status reveals itself in humor as “a tendency toward self-mockery or self-deprecation” that can nevertheless be projected outward and traced from slave times through minstrelsy and vaudeville to the stand-up comedy of Richard Pryor.61 Yet it also shows forth as a rhetorical mode of usurpation with regard to the longstanding oppressions of dominant white culture. African-American humor is truly Black humor, in both senses of the term. It is the “laugh by proxy,” in Langston Hughes’s words, cast onto the Other while being boomeranged back to the Self. It is about making Blackness present in order to see selfhood through somebody else’s eyes—to look upon oneself as if a stranger, and some other as more familiar than one might like them to be.

The resistances and retaliations endemic to African American humor are similarly about self-liberation in the face of originary subjugation.62 On one hand, this kind of humor serves as a check on white culture. On the other, it stands to reckon with the (comic) spirit of Black experience.63 There are clear, albeit discomfiting, overlaps here with what is alternatively characterized as ethnic humor in the United States. At least one has to do with the common sense of insider–outsider relations, centers and margins, simplifications and generalizations, and the habits of identification and division that reveal a “web of ambivalence, cooperation, and anxiety,” even more so when humor is used to exemplify these awkward imbrications.64 All of these and more characterizations reflect the uncommon grounds of foundational principles for the American Way, or what Hughes might describe as the awe—whether awesome or awful—to be gleaned from our own smiles in a mirror. Nevertheless, they remind us of something crucial: “Black American humor began as a wrested freedom, the freedom to laugh at that which was unjust and cruel in order to create distance from what would otherwise obliterate a sense of self and community.”65 If black-and-white (and Black and White) characteristics of US Americanism are gray areas of complex social, political, and cultural histories, then the contingencies of wartimes present even larger points of reference for grappling with the ordinary entailments of any national character. Resistance is a mode of retaliation, just as self-presentation risks self-negation.

Harrington’s editorial cartoons are at once exemplary and exceptional in this brief sketch of African American humor. First of all, they embody a comic construction of proximity, taking on nationalistic notions of selfhood by combining self-construction and self-understanding with self-criticism. In part, this meant that during World War II as well as the Cold War he had to openly and explicitly engage “the contradiction between America’s fight against the racism of fascism abroad and its own racist practices at home.”66 It also meant that he had to reconsider representation itself as a species of self-delusion, making the rhetorical act of showing and telling it like it is a complicated comic art of seeing things differently. Visual humor was a means of making images of Black experience even more complex and nuanced rather than guilelessly liberating. Put differently, Harrington humored Black experience while rendering it comical in order to pursue anti-racism and point out the contradictions, absurdities, and incongruities inherent to racialized travesties. In May of 1942, Harrington was actually criticized by members of the Black community for using his famed character Bootsie to belittle African Americans. He replied that “there are some imbeciles left among us who find time in between bone-pulverizing bombings, mass murder and other sadistic forms of civilized recreation, to laugh.”67 What Harrington was also saying in his unsubtle mockery of foreign warfare and warring dispositions and deeds at home is that, sometimes, it is the one who directs laugher toward oneself who best recognizes the humanity in others.

This is why Harrington’s caricatures of Black children are so potent: they strip the machinations of white men and war machines of their “civilized recreation” by proclaiming that the comic spirit is a human spirit.68 His editorial cartoons are squarely in the Black tradition of humor, especially with their combination of caricature “with a gritty evocation of reality.”69 And yet they make a more universalized humanity even more present by making it into something that exceeds Blackness or whiteness, let alone the complicated issues of ethnicity and race. Harrington goaded Black and white audiences alike to use the misfortunes of wartimes as comic resources for working through the riddles of warring spirits so endemic to US Americanism—or, in the words of poet Georgia Douglas Johnson, to “Unriddle this riddle of ‘outside in’ / White men’s children in black men’s skin.” Plainly, any self seen in the comic looking glass is at least partly seen in the guise of the other. Children are Harrington’s foil for “humoring” such an outlook.

The Black Children of War

To understand Harrington’s decades-long use of Black children in caricatures of US war culture is to understand just how much his take stands in stark contrast to the ideas of dread and deference that surrounded images of childhood in white America. Some in the Radical Left viewed children as the last and only hope for egalitarianism. Others saw them as victims of cultural contamination. Discourses of school integration had Communist threads, in which some people argued that any kind of mixing “would undermine the fabric of American society.”70 These threads were tied to everyday consumer activities as well. Comic books. Films. Television shows. Advertisements, like Lyndon B. Johnson’s infamous “Daisy Girl” campaign spot preceding the 1964 presidential election. Card games for kids, too. For instance, in 1951 the Red Menace emerged as a visual resource for imagining the Communist threat alongside principles of Americanism. The card set was released by the Bowman Trading Card Company and coupled with packages of bubblegum. There were five in a set. Each contained a graphic image of Cold War conflict (from illustrations of “GENERAL ‘IKE’ IN COMMAND” to a dour sketch of a “GHOST CITY” overseen by a Grim Reaper in the clouds), all under the aegis of a “Children’s Crusade Against Communism.” The cards amount to what Margaret Peacock calls “innocent weapons” for young (white) citizens,71 and they traded in obeisance and fear.

The Black children of Harrington’s caricatures are an altogether different stock in trade. They were rife in his cartoons by the early 1950s, and certainly from the Little Rock Nine through Brown v. Board of Education. These children were made to look upon the battle for racial separation in view of a more ubiquitous war against Communistic enemies. They were made to see redbaiting as race baiting in the wider context of Massive Resistance. The Supreme Court decision to integrate schools put children on the front lines of cultural conflict at home. Black children were made to understand these conundrums while living out a history of racial terror that had long contributed to the kidnapping of Black children by the KKK and in the lynching programs of white supremacists that animated much of the savagery in early twentieth-century America. These Black children were also urged to see themselves as the pickaninny, or the “mirror image of both the always-already pained African American adult and the ‘childlike Negro.’”72 However, for Harrington, Black children provided a haunting image of unwitting, yet no less witty and wise, outsiders within a legacy of raced-white labels for American national character.

DIVIDED AND COLORED

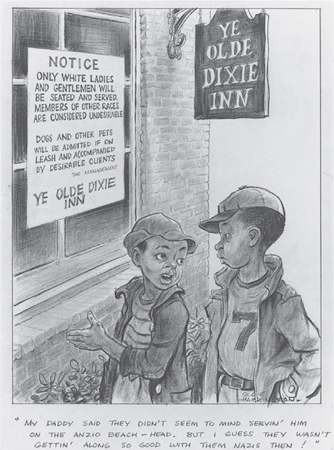

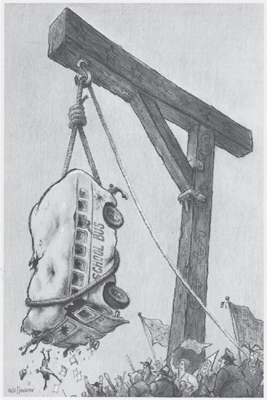

A cartoon from 1958 offers an exemplary caricature of Black children as comic foils for Harrington’s own crusade. Published under the “Bootsie” heading, the cartoon shows two Black boys walking to/from school amid a blockade of troops. The soldiers are armed with bayonet-equipped rifles, foreshadowing the paratroopers that symbolized federal enforcement of an integrated Central High in Little Rock just a year later. “Goodness, gracious Gaither,” says one boy to the other. “You reckon these fools expect us to run through this hassle every day an’ do our HOMEWORK, TOO?” In another cartoon that appeared a few days later, a Black boy, “little Luther,”73 sits on a stool in the middle of a roadway (fig. 19). He is well dressed, with a uniform jacket, neat tie, and a cap. Behind him a trio of army officers strategizes how to get Luther safely into school. In the backdrop is a collection of soldiers. One officer gives orders: “General Blotchit, you take your tanks and feint at Lynchville. General Pannick, you move into the county seat. And then in the confusion, my infantry will try to take little Luther to school!” The situation of kids in homegrown combat zones is enough to make viewers recoil at the militarization of cultural politics. Yet, as in the first cartoon showing the boys reacting to the Ye Olde Dixie Inn sign, the children speak, and in their speech they mock the relationship between principles and practice. Desegregation, on paper, made all children created equal when it came to schooling. But it did little to remove the war culture that persisted after World War II, which is why—in the second cartoon—the humor is as much in the names of the military men as it is in the image of Luther.

FIG. 19 Oliver W. Harrington, “General Blotchit, you take your tanks and feint at Lynchville,” 1958. From Pittsburgh Courier, 1958. Reproduced from a picture catalogued online for the Prints and Photographs Reading Room by the Caroline and Erwin Swann Foundation for Caricature and Cartoon. The Library of Congress and the National Portrait Gallery. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Used with permission of Dr. Helma Harrington, Berlin.

First there are the generals. The surname “Blotchit” is a portmanteau word. It invokes the idea of a “blotch,” or a blemish, and is a reference to racism. Then again there is a sense in which this blotch is a cause for desegregation to get botched up, or for the soldiers (to say nothing of the students) to botch it. Or it could directly ridicule the fact that military personnel were necessary because race relations had been mismanaged, bungled, and flubbed in the first place. This resonates with the other surname, “Pannick,” insofar as it bespeaks the “blockbusting” and “panic selling” that went along with school integration efforts.74 Here, however, “pannick” is a mockery, and perhaps even an Ebonic reformulation of racial dread. Such anxiety is highlighted as a “proteophobic expression,” amplified by the military measures required to protect a diminutive Black schoolboy and uphold “the dichotomous nature of national boundaries.”75 Finally, there is the overt reference to lynching in the fictitious town of “Lynchville.” In one respect, Harrington derides the mob of mass resisters. But the town name also foregrounds the historical endurance of what had become an outmoded, extrajudicial exercise of white power. While the practice of lynching was all but eradicated from public life by the mid-1950s, its corrupted and violent roots were preserved in civic interactions. Harrington pictures how racialized rhetorics are literally inscribed in social systems and socialization processes. He also provides an image of children in need of protection from a domestic aggressor that otherwise might proclaim to engage in warfare, ironically, only in matters of self-defense.

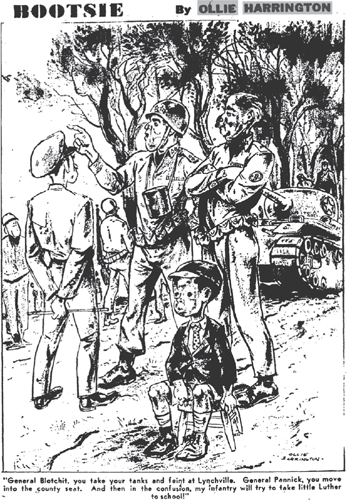

Harrington’s early renditions of Black children on the home front therefore tell an altogether different sort of American war story: not one built on ideologies of making the world safe for the American Way but rather one predicated upon a humorous struggle between the white way and the wrong way. According to Tom Engelhardt, this story is “so natural, so innocent, so nearly childlike,”76 and so ingrained in a historical sense of what victory in World War II would have looked like that the Cold War could only further impede the doing away of racism as a means of putting away childish things. Consider another cartoon from September 1957, in which Harrington laughs at the conceit of some Southern whites who treated Black children as infiltrators in an Americanism to which they supposedly should not have access. The cartoon shows a general awarding “Dixie’s noblest medal for gallantry in action” to a foolish-looking ignoramus of a soldier who apparently stood strong “in the face of a suicidal charge by several frenzied Niggra children trying to enter the General Lee Elementary School.” If the unapologetic play on the figure of the once-revered Confederate general was not enough, Harrington executed a verbal travesty of an infamous racial pejorative while parodying the Southern drawl right along with Jim Crow mindsets. This travesty lines up with the visual lampoon to portray Harrington’s view of “the ludicrous nature of American racism.”77 Furthermore, it captures the backwardness of those who held tight to de jure segregation by treating it as a de facto state of race-based war at home. This backwardness might be most explicit in a caricature that Harrington created of a mob of resisters lynching an entire school bus (fig. 20). A crowd comprised of white men and women, including a Klan member and a sheriff with a cowboy hat, chants, celebrates, and waves Confederate flags beneath a massive, makeshift hanging tree. Suspended in a noose is a battered and partially burned school bus, with its front facing downward and two Black children falling out. Seven stars are carved into the top of the scaffold, along with a few dollar signs down the support beam, which together suggest a Southern Strategy for noncompliance with desegregation.

FIG. 20 Oliver W. Harrington, lynched school bus. From Daily World, June 1969. Used with permission of Dr. Helma Harrington, Berlin.

The image of a lynched school bus is horrifying. But it is reduced to the absurd and amplified to the sublime in a different cartoon that seems to sum up Harrington’s child’s-eye view on desegregation as a metaphor for nurturing disunity in the American national character. Two Black boys are walking together in the snow. One boy is pulling a wooden sled behind him. The other says: “Man, do you realize that if we was in Alabama it would be against the law fer us cullud kids to walk on this stuff?” The image amplifies the gap between the late 1950s and 1963, a fateful year in which the Southern Christian Leadership Conference along with guidance from Martin Luther King, Jr. rallied, protested, and demanded desegregation of civic spaces as well as public schools in Birmingham, Alabama. Harrington’s cartoon reflects on an otherwise raucous and violent series of events that had roots in declarations by some segregationists that the Civil Rights Movement was a Communist intrusion on American institutions. Eugene “Bull” Connor, Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety, was chief among those who detested racial integration, and he had since 1958 refused to recognize the civil rights of Black citizens. He even turned a blind eye to the KKK when they terrorized Freedom Riders in 1961. However, in early May 1963, King and others orchestrated what Newsweek dubbed a “Children’s Crusade,” whereby students were enlisted in a march. A number of activists and parents alike expressed concern over King’s urgings and even criticized him for converting children into “civil rights kamikazes.”78 Bull Connor ordered police to forcibly remove the children from the streets. In the days between May 2 and May 5, schoolchildren marched and chanted “Freedom . . . Freedom . . . Freedom” before being met by patrolmen and crime dogs. Some were as young as six years old, and among the hundreds of children who were hauled off to jail in school buses. Others were subjected to the brutal blast of water from firehoses. Recall Charles Moore’s iconic photograph of a small group of teenagers being pelted against a brick wall, which was widely regarded as a rallying cry for social and political change nationwide. There in the mix but outside the fray were Harrington’s two Black boys trudging along in the snow, making the comically perverse observation that whiteness itself established a “dead line.” What the boys saw were racial motivations to contain Blackness through both the force of violence and rhetorical force. What they sensed, too, was that children had to bear the burden of war’s fallout on cultural battlegrounds.

WAR CULTURE, GAMED

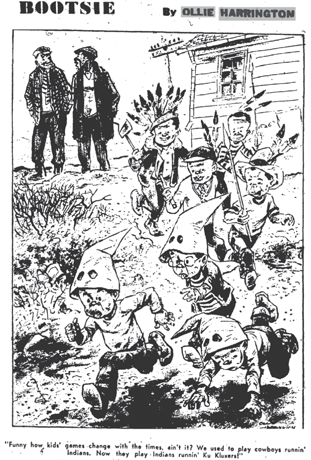

Still, it is in child’s play that Harrington really embeds his caricature of the consequences that follow from ugly warring spirits. A cartoon from February 1958 pictures four Black boys bedecked in stereotypically Native American garb wielding hatchets and spears while chasing down three others (fig. 21). Earlier that year, much attention had been paid by Life magazine and other outlets to the conflicts between “the Indians” and the so-called “Ku Kluxers.” Tribesmen from the latter group had been holding regular anti-Indian gatherings and demonstrations wherein they would burn wooden crosses and rally around bigotry and buckshots.79 In Harrington’s cartoon, the three boys being chased down are wearing white, coned hats with cutout eyeholes. The hats rest on their foreheads, revealing their boyish faces. One boy leads the escape in full stride with a furrowed brow and mouth agape. The boy next to him stumbles to the ground. Trailing behind is a young boy with glasses, fleeing with his tongue hanging out of his mouth. Two Black men observe the play. “Funny how kids’ games change with the times, ain’t it?” says one to the other. “We used to play cowboys runnin’ Indians. Now they play Indians runnin’ Ku Kluxers!” The reference here is likely to efforts of the Lumbee to break up Klan rallies in North Carolina. However, it also recollects a colonial heritage in reversing a “traditional” childhood game, “Cowboys and Indians.” Following George Herbert Mead’s concept of the Self as a collective construction, this cartoon inscribes new agency on Black children “taking the roles of others,” and on Indians as a “generalized other” with “organized reactions” to institutional (and vigilante) modes of racism.80 More glaringly, the impenitence and yet hardly innocent nature of child’s play exposes how inurement to civic strife becomes part of the developmental process for those raised to have fun in war games.

FIG. 21 Oliver W. Harrington, “Funny how kids’ games change with the times, ain’t it?,” 1958. From Pittsburgh Courier, February 15, 1958. Used with permission of Dr. Helma Harrington, Berlin.

This gamesmanship matters a great deal when “role-playing” activities extend from the confines of play to the cultural production of communities. In the company of fellow Blacks, for instance, the Black children in Harrington’s cartoon shapeshift to take on different roles based on their own impulses, flights of fancy, and constructed hierarchies. This flexibility and mobility is often compromised, though, once a Black child comes under the rules of play as determined by white children. In another cartoon from August 1959, a Black boy dressed as a pirate stands beside two white boys in matching overalls and striped t-shirts. “Hey, Dad . . . ,” the boy says to his father, who is puffing on a cigar while pushing a reel mower over a fenced-in lawn, “. . . is these cats tellin’ the truth?” the boy inquires. “They say that they don’t allow no cullud to be pirates!” There is much irony in this scene. First of all, it belies associations of piracy with blackness. Secondly, it plays on the possible ignorance of the white boys who seem to be unaware (if not proud) of the notion that they are the inheritors of a culture of pioneers and colonizers. While Blacks were so often discriminated against for some form of brutality or barbarism, there is actually a potentially stronger sense in which whites were historically the more barbarous in their own cultural piracy when they “dashed to the sea in their two-sailed barks, landed anywhere, killed everything.”81 The white boys betray the romance of rebel power, looking like children of the American Revolution.

Thirdly, it is not at all clear that the white boys were playing with the Black boy. If they were, the Black boy is out of place and unfit for integrated child’s play, especially when it is built on conflicting historical imaginaries. If they weren’t, the Black boy was clearly disciplined after the white boys witnessed him getting out of line. In either case, even the father figure comes off as an inapt arbiter. The taller, and presumably older, of the two white boys stands straight and stares up at him with a self-satisfied grin. Child’s play, like comic play, can be a powerful mode of resistance, even if it reinforces Old Ways. Harrington portrays the deformative impact on play-as-resistance when US American tradition meets matters of knowing one’s role (or place) in the national landscape. The Cold War cultural milieu intensifies this sentiment given that foreign “others” were imaged in terms of mutual and/or unilateral destruction, not coexistence. Harrington’s children are “children of Jim Crow.”82 They learned race through cultural warfare, but a type that seemed to do little in the fight against olden color lines. So it is that these children play out and re-create the sort of warfare endemic to Cold War modes of cultural exchange. Resistance for Black children is a struggle against Jim Crow in a wider, more dispersed struggle over multiple forms of oppression and discrimination. Resistance for the white children is, cruelly, self-defense.

The breadth of Harrington’s cartoon embattlement is even more striking when it is seen for the history of America it renders in the comic looking glass. An insider’s look at American national character, especially during wartimes, would easily find a people of pride. Harrington homes in on what Michael Kammen once called a “people of paradox,” namely when grappling with the troubled place of Blacks apropos the white man’s historical burdens.83 One cartoon plays on the familiar theme of characterological allowances when four Black boys are shown in a rowboat, one of whom addresses a boy in the bow. “Well first of all,” he says, “you couldn’t be Columbus ’cause the white folks wouldn’t never let a cullud man discover America!” Here again, heritages are policed according to the realities of the moment, only this time through a Black child’s view of acceptable points of national identification. But they are subjected to humor when one of the Black children openly mocks the very idea that white America has been claimed, which is to say that it has been both divided and conquered according to the will of a dominant racial group. Nevertheless, at least one of the boys wants to be Columbus (or at least a Columbus-like figure) if for nothing more than to occupy a position of prominence in the American story.

All of this is to say that Harrington’s 1950s depictions of children form the foundation for his articulation of an American national character in crisis. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy escalated the United States to war. In the process, he championed a brand of nationalism that could not withstand racist treatments of the Negro character (such as the one outlined in the infamous Moynihan Report on the “Negro Family,” published in 1965) and oversaw the beginnings of his New Frontier. Similarly, while US troops battled through guerilla warfare overseas, citizens (and, at times, the National Guard) combatted racial conflicts alongside images of what Harrington repeatedly showed to be a domestic struggle that deserved a call to sociopolitical arms. Harrington was obviously concerned about civil rights. He was obviously wary of McCarthyism. But his cartoons went even further to offer a window into the cultural structures of race-based ways of seeing the United States as a national Self, taking on the characteristically American institutions of capitalism, war profiteering, social welfare, and others in order to show how the Vietnam War (and the Cold War besides) made, in King’s words, “the bombs in Vietnam explode at home.” One particular bomb had to do with the problem of poverty.

REFLECTED, POORLY

In 1960, the KKK used a Confederate flag to extinguish the fire in the torch held up by the Statue of Liberty. At least this is what Harrington suggested in a cartoon. The United Klan has been a powerful force in the Southern states and in the US imaginary ever since the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Harrington’s cartoon is a visual commentary on the KKK. As prominently, it is a remark on the fact that the Statue of Liberty was erected in part to commemorate freed slaves, and so to symbolize the universality of American freedom. There is a broken shackle and chain on the platform next to Lady Liberty’s foot. This imagery assimilates easily into the narrative of immigrants who are themselves looking to break free from the bonds of tyranny and oppression. The Klan co-opted the symbolism of liberty as an emblem of white freedom. Harrington took it back to draw a crooked and colored line from impoverished American values to actual penury.

That President Lyndon B. Johnson had to declare war on poverty while serving as commander in chief of a foreign jungle war is a telltale sign of his sense that, with munitions or metaphors, “war is always the same.”84 King reflected on this in March 1966 when he wrote that the “assembled armies” of civil rights activists fought over the configuration but also “the content of freedom.”85 King focused on the enduring issues of employment, housing, and urban distress that sustained socioeconomic battles and the revolving door between public culture and (armed) conflict, not to mention conflicts of national interest. This is why King declared “an all-out war on poverty,” not just in the ideals of a “Great Society” but also in the ground operations carried out on American city streets. As US involvement in the Vietnam War amped up in the years between 1965 and 1968, Harrington drew attention to the casualties of the War on Poverty. The Black children in his cartoons from 1969 through 1975 reveal a sense that America is a poor reflection of its own ideals when it actively neglects, let alone represses, entire communities. More generally, Harrington’s Black children are evidence that the United States was fighting the wrong fight in Vietnam. The plight of the young at home represented a need for moral over military rectitude. In April 1965, during his “Peace Without Conquest” speech at Johns Hopkins University, President Johnson identified the materials of armed conflict (guns, bombs, rockets, and warships) as the “necessary symbols” of human folly. Tellingly, he transitioned to this sentiment by way of a statement about poverty as the index of disorder.86 Harrington’s cartoon of Lady Liberty is a necessary symbol. His Black children are unfortunate manifestations of American folly—and failure.

While more and more attention was paid to battles overseas, less and less was done to ensure that equal civil rights were actually operationalized. The so-called wars against poverty and drugs typified the increasingly transactional nature of race relations as a line item in the “welfare state regime.”87 It eventually folded into a broader policy of “Vietnamization” whereby public responsibility took on a form of pacification in place of political priority. For Harrington, this meant the disarmament of important programs and a disproportionate picture of what Eisenhower once called “just relations”—two conditions that Harrington approached with Black children no longer as weapons but rather as casualties of war. Following Joseph Boskin and Joseph Dorinson, the humor in the depictions of these children is as much about survival as it is about subversion.88 The humor is replete with a realism that chides a majority white culture, and it emphasizes racialism as the lens through which one might expand the looking-glass view on US cultures of war.

Crucial to Harrington’s even sharper cultural criticism is the publication of his work by the Daily World in 1968, wherein the tenor of his caricatures increasingly appealed to racial warfare as a byproduct of legislative maneuverings and war as an exemplification of the national interest. In April 1969, President Johnson’s attempts to “Americanize” the Vietnam War with a broadened military campaign and a domestic agenda that emphasized civil rights had done little to secure victory on either front. By many accounts, the War on Poverty had not been won. Johnson’s outgoing State of the Union Address was thus in part an admission of defeat. “Urban unrest, poverty, pressures on welfare, education of our people, law enforcement and law and order, the continuing crisis in the Middle East, the conflict in Vietnam, the dangers of nuclear war, the great difficulties of dealing with the Communist powers”: all of these problems persisted.89 However, when President Richard Nixon took office, he converted the War on Poverty into something of a covert war, conducting law enforcement, welfare programs, and so on with little fuss or fanfare in order to devote his attention to ending the Vietnam War. Yet his own “Vietnamization” tactics represented an overall ideology that pitted deficiency against dependency, meaning that capitalism was the antidote to Communism just as free market economics was the corrective to paternalistic forms of protectionism. It was to be a mode of so-called peacemaking through widespread withdrawals of support.

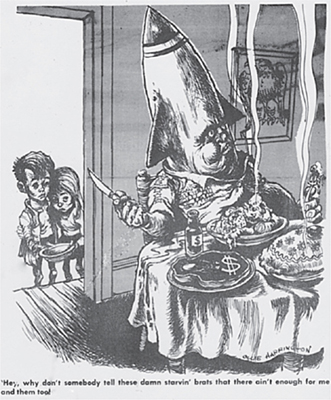

The irony is that this policy was accompanied by assaults on Cambodia and a general escalation of bombing operations in northern Vietnam. Consequently, Harrington zeroed in on the role of US military generals as figureheads for the military-industrial complex. In a cartoon from April 1969, this figure appears in full dress uniform, with an actual warhead for a head, sitting at a table on which a steaming spread of food waits to be consumed (fig. 22). The figure personifies the spoils of preparing for and waging war. And, not unlike Uncle Sam, it provides a picture of the nation. Each food item from an enormous steak to a pile of vegetables to a bottled drink is branded with a dollar sign. On a wall behind him is a framed picture of an American eagle. On the other side of the cartoon, standing behind General Warhead just beyond an open door, is a pair of young children, a boy and a girl. Together they hold each other as well as an empty bowl and look upon the Rabelaisian scene with despair while their knobby knees support malnourished bodies. Interestingly, these children seem to be white and thus defy the racial implications of social welfare programs that many at the time would have come to expect. Harrington, though, seems to make a bigger statement, which is that combat orientations cloud thinking, and lead to circumstances where battle provisions (whether on a literal battlefield or in policies of economic warfare) circumvent the will to provide for the nation’s children. Here, the boy and girl typify the welfare of all children of war and thereby allude to the Statue of Liberty and its implication of a poor, huddled mass. This is most apparent when one considers the hawkish words of the talking warhead: “Hey, why don’t somebody tell these damn starvin’ brats that there ain’t enough for me and them too!” As much could be said of the stake in American pride and principles that Harrington’s cartoon implies.

FIG. 22 Oliver W. Harrington, “Hey, why don’t somebody tell these damn starvin’ brats that there ain’t enough for me and them too!,” 1969. From Daily World, April 13, 1969. Used with permission of Dr. Helma Harrington, Berlin.

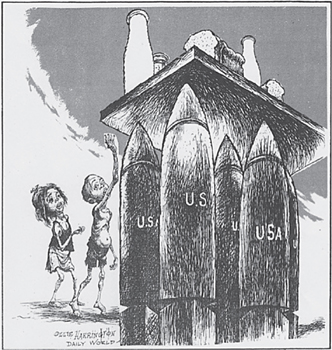

With hints of aversion to the war industry and even to US imperialism, as well as intimations that mistreatment of children amounts to war crimes, Harrington homed in on what political activist and social democrat Michael Harrington called in 1962 “the other America.” The Otherness in this one of Two Americas is defined by the tension between “the right war at home” and “the wrong war in Southeast Asia.”90 Consider a cartoon from the Daily World in July 1969 (which was reprinted a number of times from 1971 through 1977). The cartoon features two emaciated Black children reaching out for bread and milk that sit atop a tall table (fig. 23). Missiles, emblazoned with the acronym USA, stand out as the table’s legs that keep a tabletop towering over the children. The image is emblematic of the imbrication of a culture of poverty and a war culture. It captures the idea that everyday life was sustained by the right of military might, that even if war was provisionally swept out of public view it still propped up the table, and that various forms of political force determined access not only to basic needs but also to democratic principles—the very stuff of a free and equal existence. In addition, the cartoon channels the popular antiwar sentiment of bombing for peace, an almost laughable notion positing that the same practices and policies that were put in place to support the national interest were the very things that could also destroy it. This went for the Vietnam War. It went for segregationist and prejudiced ideals in government programs, too. And it impacted both foreign children and Americans.

FIG. 23 Oliver W. Harrington, kids at the war table, 1977. From Daily World, April 2, 1977. Used with permission of Dr. Helma Harrington, Berlin.

As horrific as the image of children starved of a human right appears to be, there is humor in the ugliness made plain by the warring impulses of the American Way. It is humorous because it reverses the standard approach of making the grisly luridness of a situation seem ludicrous in order to ease the anxieties of children by making children the embodiments of inhumanity. As Wanzo notes, many of Harrington’s caricatures relied on a “realistic aesthetic” that put “a perverse twist on stereotypical representations of the black child.”91 The bodies of suffering Black children are comic images of real bodies. Still, the fantastical prominence of missiles over meals for children appears as a cruel joke on this very aesthetic, a self-reflexive gesture to uncertain futures to be built on painful pasts that subjects adult onlookers to an image of national selfhood as an abject object. The children are pitiable. The adults who make their plight possible are loathsome. For readers of the Daily World, such an imbrication of horror and humor would no doubt have been met with feelings of freedom and relief. Blackness is not buffoonish here. It is the epitome of bathos. If laughter is the only weapon humans have against an absurd world largely of their own creation (as Mark Twain once said through the mouthpiece of Satan), then it is borne of black humor in this caricature, and its laughter is dark, indeed. Still, as with much humor that emerged out of the Civil Rights Movement (and slave cultures before it), humor makes it so that matters of cultural famishment can be put on the table as topics of both American warfare and the American democratic experiment. Bulging armaments juxtaposed to gaunt little bodies create an abject scene. Even worse is the inkling that both are the consequences of perverse war mentalities, feeding into a national character that might treat Black children as collateral damage at worst or, at best, as mere “brats” unworthy of table scraps.

There is a compelling merger of the nation-state with national character here in the image of two children who are twice bitten by the hand that does not feed them. At this point, the nation-state had begun to move away from policies around social and racial justice. Even before he was president, Nixon was against “forced integration” of either schools or neighborhoods. In keeping with a general sense that different races occupied different communities, he therefore kept a relatively low profile vis-à-vis civil rights after 1970. When he did speak out on the issue, he tended to align antiwar protestors (whom he even called criminals) with Black power leaders. Moreover, Nixon appealed to the “silent majority” in suggesting that enough was enough with civil rights, inciting a general attitude among those opposed to him that the two-front war was a white man’s burden but a Black man’s fight. The national character, in kind, was characterized as caught in a state of exception. This was apparent in President Nixon’s burial of the civil rights agenda in policies of “Vietnamization,” which resulted in a sort of “Americanization” of Black culture at home. We are not One America. We are at minimum Two Americas. This much was black and white in the folly of Nixon’s interest in forcing an already-deprived population to fend for itself.

In a cartoon from August 1971, the humor in Harrington’s caricatures of Black children turns the tables. It shows a US military plane at the top of the frame. As it flies from right to left, the plane drops both bombs and supplies to an undisclosed location below. It is patently ridiculous, on first glance. Who would use carpet-bombs to drop off aid? Harrington is critiquing the bombing campaigns that characterized the US air war against the North Vietnamese. He is clearly placing children in a proxy war with the United States abroad and children on the home front. However, there is also bare reality in the cartoon’s indication of governmental dealings with civil rights, which were often approached through a lens of military campaigning. Along with the bombs in the 1971 cartoon are boxes containing “Diet Tips,” “Anti-Baby Pills,” medical supplies, and, perhaps most disturbingly, “Kid’s Books.” In many ways, Harrington insinuates that this is precisely the manner in which federal support was provided to Black communities. First, given the clear allusions to food stamps, child welfare programs, and crime prevention, Harrington links state repression to the Vietnam War by showing the men, women, and children who suffered from policies that left cities and schools in ruin. Second, the cartoon mocks the idea that any work against “the system” was either un-American or antiwar since the United States aimed to destroy certain living conditions and replace them with a new way of life. Third, and finally, Harrington demonstrated an official policy of dealing with problems from a distance, and furthermore making them utterly transactional. The cartoon closes the loop between armed conflict abroad and domestic culture wars.

At the end of the day, for Harrington, the welfare of children is a contact point for understanding the character of a nation. The United States’ participation in the Cold War generally and the Vietnam War in particular displayed a national character that largely ostracized Black culture. Caricatures of children have such comic rhetorical force here because children are the most vulnerable outsiders within an otherwise wealthy and well-off nation. Consider, then, a cartoon from April 24, 1973, that shows a grotesque Cold War vulture gripping a diminutive Black boy in his talons and carrying him out of his urban environment. Inscribed on the inside of the vulture’s left wing are the words “WILD PROFITEERING,” and on the white shirt of the Black child are the words “OUR KIDS.” Later, Harrington built on this image of a false promise of freedom from war by tracing Nixon’s follies to President Jimmy Carter’s subsequent failures. In 1977, this meant drawing Black and white children under a table eating leavings while an enormous fat cat with a bib labeling the arms industry feasted on a bowl of the “BIGGEST BANG, BANG, BANG, BUDGET EVER!” President Carter continued America’s military build-up, investing in NATO while putting stock in neutron bombs. For Harrington, this meant the continuation of wartime policies that had long put children of multiple races against “military fellers” who starved the young so that the national defense could thrive. It meant that pigs—which in earlier cartoons had symbolized police, “corporate monsters,” and financiers chaining up the “free” world—became the symbol for “HIGH-FINANCE GLUTTONY,” with one seen gulping down a city hospital alongside a kindergarten, church, and university building. And it meant that, by the end of February 1978, the Cold War vulture had transmogrified into a “CAPITALIST CRISIS,” feeding a rat of “RACISM” to its young. There would be no “lasting peace,” in President Carter’s words, so long as war was the best of a bad lot for securing American values. Casting the country’s lot with armed conflict across the Cold War meant over and again exposing the follies and failures of American national character. For Harrington, these follies and failures were generational things.

Conclusion: American Children, or Cartoon Progenitors of the People

It is fitting that the Vietnam War is now regarded as a campaign of Lost Innocence.

The Cold War era confirmed war itself as an American pastime. It codified the homegrown humbug in cultural warfare. In Harrington’s cartoons, it generated images of US American national character in terms of what Twain might call “high-grade comicality.” The absurdities and grotesqueries in Harrington’s caricatures of Black children gave way to the truths and consequences of living in the adult world. These children were drawn as the Fathers and Mothers of wisdom, given their wartime experiences. They were the embodiments of a nation in and out of character, living down its racist legacies while living up to its reputation for waging war on the basis of democratic principles and the collective self-interest. In Harrington’s cartoons are primal scenes of self-loathing that emerge when Black children of war are the images reflected in the comic looking glass.