Introduction

This book is about developing mastery over obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in the long term. It’s about not just living despite OCD, but living joyfully with the disorder. In the pages ahead, our aim is to explore how the use of mindfulness and self-compassion can contribute to this project of living joyfully with OCD, both by offering new tools and perspectives and by enhancing traditionally effective ones.

OCD is a psychiatric condition characterized by the presence of obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are unwanted thoughts that are perceived as intrusive and repetitive. Compulsions are physical or mental behaviors aimed at decreasing the discomfort associated with obsessions. The presence of obsessions and compulsions becomes a clinical issue when there is a related impairment of functioning or quality of life (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

OCD can manifest in a variety of ways. It is not possible to list every kind of obsession and compulsion here, but more typical themes include:

- Contamination: Excessive concern with germs, bodily fluids, chemicals, and the like

- Checking: Excessive concern with being responsible for making sure things are as they are “supposed” to be; for example, doors are closed and locked, appliances are powered off, items are where they belong, and so on

- Just right: Excessive concern with symmetry or exactness

- Harm: Excessive fear of committing acts of violence toward oneself or others

- Sexual themes: excessive intrusive thoughts about sexual orientation or sexual appropriateness

- Relationship: excessive concern with whether a relationship is “right”

- Hyperwareness/Sensorimotor: Excessive concern with awareness of involuntary processes such as blinking or swallowing

As obsessions are unwanted, intrusive thoughts, you become uncomfortable when you become aware of them. It bothers you that the thought is there, in part because it just doesn’t line up with what makes sense for you and your identity. You may also associate the thought (specifically, the words or images that make up the content of the thought) with things that are upsetting or disgusting. Naturally, like the secret “normie” that you are, you don’t like feeling bad. So you set out to get some certainty that your obsessive thought is harmless or inaccurate, or at least that it will go away. Once you have achieved this in your mind, you give yourself permission to move on, or to return to what you were doing before the obsession so rudely intruded. This behavior is a compulsion.

The problem with compulsions is that they work—at least a little bit, some of the time. Compulsions usually provide some modicum of relief from the pain of your obsessions. This triggers a fascinating process called negative reinforcement. By removing pain, compulsions trigger the brain to calculate that the compulsion is tied to the obsession in a manner that should be repeated. This not only increases the urge to respond to obsessions with compulsions, but also increases your sensitivity to the obsession in the first place. When it makes itself known, it does so along with the message that it requires a compulsive response because it feels like a really big deal.

It’s like you’re getting slapped in the face for no discernible reason, then you stand on one foot and the slapping stops, so your brain thinks you should stand on one foot whenever you see a hand approaching your face. The more compulsions you do, the more you reinforce the cycle. The obsession grows stronger, the drive to do compulsions grows along with it, and around and around you go. To beat an obsession, you need to starve it out, which means you need to target and eliminate compulsions.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of psychological treatment that emphasizes challenging distorted ways of thinking about our experiences (cognitive) and making changes in behavior that enable you to face your fears (behavioral). A specific form of CBT called exposure and response prevention (ERP) works by having you gradually put yourself in the presence of the thoughts, feelings, or experiences that cause you discomfort (exposure) while resisting attempts to use physical or mental compulsions to neutralize or avoid the discomfort (response prevention). Relatively recent research has shown that exposure therapy violates your brain’s expectations about the meaning of the OCD trigger, and in doing so, helps your brain develop inhibitory learning. Over time, the inhibitory learning suppresses the previous fear-based learning about the OCD trigger (Craske et al. 2008). Further, the more you do ERP, the less anxiety you may experience in the face of the same triggers—a process called habituation.

One form of CBT, known as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), emphasizes openness to thoughts and feelings and a focus on the pursuit of clear values. Different people may respond differently to traditional CBT and ERP approaches, ACT approaches, or some combination. Traditional talk therapies or therapies that focus primarily on relaxation are less likely to be effective for OCD.

Mindfulness is the ability to observe your experiences without judgment. Self-compassion is the ability to relate to yourself with the desire to reduce your own suffering. Together, they form a skill set that can aid you in making healthy decisions about your OCD and maintaining a stable attitude about the disorder every day, even as it waxes and wanes throughout your lifetime.

About the Authors

Jon Hershfield

One of my earliest memories is an OCD memory. I was about five years old, and it began with me telling my mother about a dream I had had the night before. I began to wonder why I was doing this and whether or not there was something wrong about having the dream or wrong about sharing it. I shrugged it off.

Later that day, playing with my friend, I remember sitting on the floor under a table, a bowl of carrots between us, pretending to be rabbits. I felt a tug in my throat, like my stomach was trying to eat my Adam’s apple. Something was wrong. I had done something wrong. I was wrong, somehow. I started to cry. I started to scream. My friend became upset, his mom became upset, everyone was very upset. My friend’s mom asked, “What’s wrong? What is it?” I forced the words through tears: “I—don’t—know!!!!!” I consider this my first experience with OCD.

Striving to overcome my lifelong OCD challenges has been a series of ups and downs, with a variety of big wins and dark times throughout the years. It is a story that consistently gets better, but it remains an ongoing journey. Everyday Mindfulness for OCD is written as much for me as it is for you, the reader. It is a reminder that developing mastery over many years is a privilege. It is an exploration of tools, techniques, interventions, and mostly attitudes that make long-term management of this disorder a worthwhile endeavor, and I hope it serves as a helpful companion on your path.

Shala Nicely

I’ve had OCD all my life, but I went for years not knowing that the horrific thoughts that plagued me and the strange little rituals in which I participated had a name. Even after I was diagnosed, I spent many more years in and out of therapy before stumbling upon the evidence-based treatment for OCD, exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), during the 2010 International OCD Foundation conference.

Since learning about this life-changing treatment, I have done two things: I went back to school to get a master’s degree in counseling so I could help others with OCD get the right treatment faster than I did, and I have made ERP an integral part of my life. I know from personal experience how dreadfully hard ERP can be, so I’ve spent the last several years trying to figure out ways to make it more palatable for my therapy clients and for myself. What I’ve found is that learning to not just do ERP, but to have fun with it, doesn’t just make your life good—it can make it great, even with OCD quietly tagging along in the background.

I think it’s safe to say that in the years since that fateful conference I’ve had enough experience with life with OCD and with ERP to say with conviction that even if the cards we are dealt have OCD written all over them, we can still hold a winning hand.

About This Book

If you are new to the disorder, the tips and tools in this book can still be instrumental in your recovery, but we recommend you start with CBT/ERP treatment from an OCD specialist or, if that is not an option, self-treatment using one of the self-help resources available (see https://iocdf.org/books/ for a comprehensive list). After that, you may find this book to be most useful as a collateral resource. Medication may also play an important role in your recovery. Though not every person with OCD takes medication, many find it an important factor in treatment when it helps to reduce the intensity of intrusive thoughts and increases the ability to resist compulsions. To assess whether medication could play a role in your treatment, we recommend a comprehensive evaluation from a psychiatrist.

This book is like a user’s manual for long-term management of OCD, divided into three parts: mindfulness and self-compassion, daily tools and games to promote joyful living, and different aspects of successful long-term mastery of the disorder. Part 1 will discuss two foundational elements for promoting mastery of your OCD: mindfulness and self-compassion. The shift in perspective that mindfulness affords us can be used to enhance what works in navigating OCD and to reduce what doesn’t. In chapter 1 we will review basic mindfulness concepts as they apply to OCD and the role of meditation as a tool for increasing mindfulness skills. In chapter 2 we will explore the essential component of self-compassion. You are the person living with this disorder, and you are the person who is going to master it. So learning to love and support yourself with compassion is a key element in learning to stay on top of your OCD. These two concepts, mindfulness and self-compassion, will be woven into each of the following parts of the book. We therefore recommend that you complete reading part 1 before getting into the tips and tools in part 2.

Part 2 is composed of tools, tips, and games that you can incorporate into your daily experience of OCD. In chapter 3 we describe a variety of meditation and self-compassion exercises, as well as tips for thinking more mindfully about your unwanted thoughts. Chapter 4 includes a variety of ERP exercises (or “games”) for tackling the OCD head on. Not every one will click for you, but you can try them out and decide which ones are keepers.

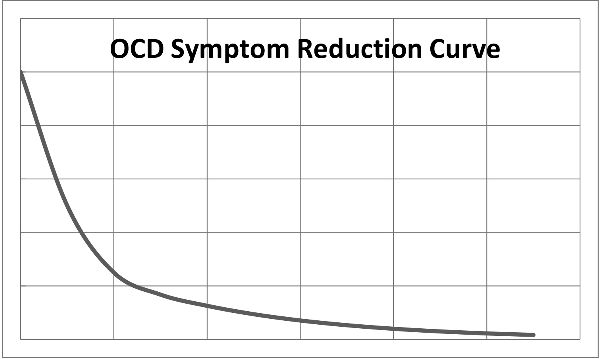

What sets OCD apart from other so-called “chronic” conditions is that you can expect to get better and better as time goes on if you use the right tools and do your maintenance work. One way to think about long-term recovery from OCD is in the form of a curve:

Once you start to make headway in treatment, improvement can be pretty dramatic. Your symptoms may persist for some time, but once you get some momentum going, your symptoms may diminish rather quickly (think weeks or months rather than years). But as you get better and better, this progress slows and never really gets down to zero. You indefinitely approach mastery over OCD, but you never arrive at the complete and total absence of the disorder. Part 3 therefore focuses on issues related to this indefinite approach, such as taking ownership of your OCD, addressing lapses and relapses of your symptoms, and understanding OCD in the context of the larger system in which you live. Living with OCD as a long-term project means persisting in developing your mastery over it. If mastering OCD is a new effort for you, we hope this book takes some of the mystique out of what lies ahead. If you’re an old pro, we hope this book offers you some new tools for your toolbox and maybe even adds a kick to your step.