Chapter 4

ERP Games for OCD Mastery

Exposure and response prevention is a core element of developing OCD mastery. In this chapter you will find brief and direct exposure strategies and other tools for daily living. We have framed these exposure exercises and tools as games you play with your OCD, because toying with an adversary is more effective than always being on the defensive. These are not meant as a substitute for a structured ERP program with an OCD specialist, but as a collection of tools you can use throughout your journey with OCD.

The New Meaning of J-O-Y

If you look up the word “joy,” you’ll find it defined as “a feeling of pleasure” or “happiness.” While there is nothing wrong with those definitions, for people with OCD, they are just not enough, because it doesn’t tell you how to get there…how to find joy. Being in your head much of the time makes joy such an elusive concept. Over the next few pages we are going to go over some basic guidelines for coping with OCD that can bolster your resolve to do ERP and engage your OCD masterfully. And it conveniently spells J-O-Y as a reminder that you are as worthy of great pleasure and happiness as anyone else.

- J: Jump In

OCD is playing a game with you, using wordplay, illusions, tricks, and taunts to dominate you on the board. It is banking on your resistance to experiencing anxiety to deceive you into throwing the game. But what if you turned the tables on OCD, spread your arms, and embraced discomfort? As we explore this concept, you’ll learn how to use ERP “games” to jump into the mosh pit of your OCD and stop running for safety.

- O: Opt for Greater Good

If you are willing to make space for or even welcome anxiety, your mind is then freed up from plotting how to get rid of discomfort. Now it can focus on what it is you really want out of life, your goals and values. Here we want to look at ways you can outsmart the OCD by shifting your focus toward behavioral goals that matter to you, and not just frustrating compulsions.

- Y: Yield to Uncertainty

Let’s take a few minutes to drill down deeper into each of the three components of J-O-Y.

What It Means to Jump In to Discomfort

If you polled one hundred people in a room, we bet that not one of them would say that discomfort—whether it’s anxiety, pain, ickiness, or some other uncomfortable feeling—is enjoyable. And you get this, right? Because honestly, when you do a compulsion, you’re doing it for one reason only: to get rid of anxiety, disgust, or some other feeling you have deemed intolerable.

The FFF Response Is Your Friend

Since anxiety is one of the most common feelings of discomfort we’d like to eliminate, let’s focus on understanding it a little better. Anxiety is a by-product of the fight, flight, or freeze (FFF) response. When your brain thinks you’re in danger, it sends certain chemicals rushing through your body to get you ready to fight off an attacker, flee from danger, or freeze and hope the predator doesn’t see you. Your interpretations of those physical sensations manifest as the emotions of fear (the term used if a threat is present) or anxiety (the term used if a threat isn’t actually present) (Pittman and Karle 2015).

The FFF response, working as it was designed, creates a surge of energy that gets you away from danger and then subsides once the danger has passed. Reid Wilson (2016) describes it well: “Somewhere on the open savannahs of Africa, an impala explodes into a spectacle of zigzag leaps to confuse and outrun the claws of a cheetah. Once the cheetah gives up the chase, the impala will shake and tremble to release the leftover bodily tension after narrowly escaping death. Then it will gracefully dash off to rejoin the herd” (p. 35). Afterward, the herd of impala don’t stand around twiddling their hooves, worrying about the next attack. They don’t seek reassurance from one another, like, “Whoa, Bob, did you see that? Thought I was a goner for sure! What if he comes back?” No. They go, “Oh, hey, look, grass.” And they graze. That’s the FFF response working beautifully as Mother Nature intended.

The FFF response can also be triggered by perceived threats (that is, things that seem threatening but actually aren’t), and unfortunately, once the FFF response is activated and you feel physical sensations of anxiety, it can be hard to tell whether the threat is real or imagined (Pittman and Karle 2015). Because the “dangers” of our modern world, whether real or not, aren’t always as clear-cut as a lion catching or not catching a gazelle, your brain sometimes doesn’t know when it’s safe to turn off the FFF chemical pumps. So we can feel what we call “anxiety” long after the initial surge of the FFF response (Sapolsky 2004).

Anxiety is just your brain’s way of helping you out, whether you asked for it or not. Consider how you even know you are anxious in the first place:

- Increased heart rate: helpful for energy if you’re planning on fighting or fleeing

- Rapid breathing: injecting the brain with oxygen, making you more alert and aware of your sur-roundings

- Tense muscles: helpful for fighting, fleeing, or staying absolutely still

- Tingling in the toes and fingers: this is the blood leaving your extremities for your major muscle groups for the kicking of butt

- Obsessive thoughts: a laser-like focus on the “threat”

- Racing thoughts: helpful for picking out exit or attack strategies without losing focus on the threat

- Irritation and impulsivity: a helpful emotional state to promote quick problem solving

If the threat were real, you’d be grateful for the help of fear. But since the threat is mostly or entirely a construct of the OCD mind, the discomfort can be a major burden. But is this feeling going to kill you? No. It feels like it is, because getting your body ready to fight or flee is intense business. But it’s not going to hurt you. One of the major obstacles people face in treating their OCD is the tendency to focus only on eliminating fear and anxiety. In fact, when we spend too much time in treatment trying to reduce anxiety, we actually play into the OCD’s lie about anxiety—that it is a toxin, and if you allow it to build up in you, it could poison you. It is discomforting when we are not choosing anxiety, but anxiety itself is not dangerous.

For those of you who may enjoy a scary movie, notice that the fright induced by the movie might bring about an urge to cover your eyes, but is unlikely to bring about an urge to leave the theater. You came to the theater with the intention of doing something you knew would cause this feeling, and your understanding of this feeling is that it is perfectly fine to experience it. It’s when discomfort intrudes in circumstances that you are not controlling that you become motivated to escape it. When we try to escape things that are not dangerous, we just end up with dangerous beliefs about those things.

How We Feed Anxiety by Fleeing Anxiety

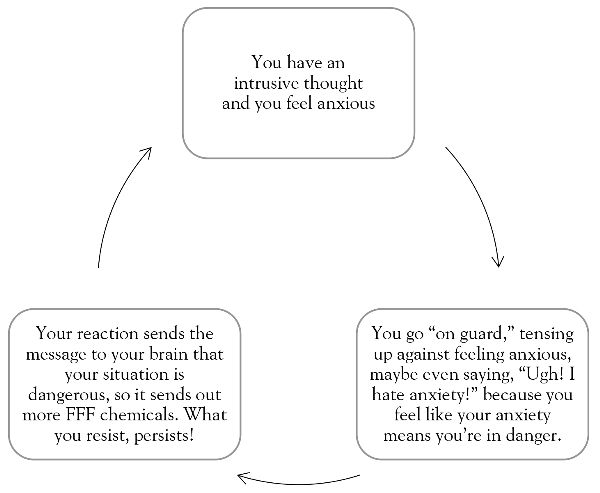

Managing your anxiety is somewhat paradoxical, in that our natural response of pushing anxiety away can actually intensify it instead. In other words, by treating anxiety as a threat, it motivates your brain to give you what you need to deal with threats: anxiety. In this way, people with OCD often find themselves caught in a loop of ever-increasing discomfort, responding to OCD triggers with anxiety and then responding to that anxiety like it is dangerous, only to produce even more anxiety:

Can you relate to this? Have you ever been frustrated by how your anxiety seems to stick around when you most want it to leave? Your efforts to flee from anxiety only trigger it to chase you, much the way an impala triggers in a cheetah an urge to pounce. But what happens if you do the opposite of trying to escape, by jumping in and embracing your anxiety? You get a much better result!

Winning by Wanting

There’s a saying attributed to both Dale Carnegie and Warren Buffett: “Success is getting what you want. Happiness is wanting what you have.” (Carnegie 2016). With OCD, sometimes you aren’t going to get want you want (peace, freedom, time without OCD bugging you), even if you’ve been in recovery for years, because OCD is going to take advantage of times when you’re vulnerable to try to take control again. However, if during those times you say to yourself, “Hey, I feel the anxiety right now. It isn’t going to kill me. In fact, I’m going to jump in and embrace it, because this is a good opportunity to practice my ERP!”, you turn the tables on your OCD in several ways.

First, you are allowing your brain to tolerate fear, which it needs to do in order to learn during the exposure process (Craske et al. 2008). Second, you are allowing yourself to fully experience the anxiety by embracing it, giving your brain an even better dose of learning (Craske et al. 2008). Third, you’ve wrested control of the experience away from OCD by saying that you are fine with anxiety being there. Essentially, OCD is banking on the idea that you are unwilling to experience anxiety. What if you were more than willing?

How to Opt for the Greater Good

At the beginning of this book, we talked about how people with OCD are noticers. They notice potential misunderstandings, potential mistakes, potential threats, and more. On the other side of the spectrum, they notice humor, creativity, compassion for others, and more. Long-term mastery over OCD is not the elimination of this special kind of mind. It is learning to fall in love with it.

To help maximize use of this special kind of mind, you’ll want to adopt the second component of the JOYful attitude: Opt for Greater Good. As Jeff Bell describes it in his 2009 book When in Doubt, Make Belief, your “Greater Good” is composed of two sides of the empowerment coin. One side is your purpose in life; the other is how you can be of service to others.

Purpose

You can understand purpose as what you would like to look back on as a lifetime achievement. Your purpose might be to be a certain kind of mother, or a pioneer in your profession. Or it can be something simple or abstract like being kind to others or experiencing peacefulness. And your purpose isn’t fixed, either; it might change as you go through life.

Service

You can understand service as any way in which your efforts improve the lives or experience of others. This doesn’t always have to be literal, as in starting a charitable foundation. There are a variety of ways you might be of service to others. You might use your experience to help develop the talents of others as a manager in your company, or entertain and enlighten others with funny and memorable stories, or simply listen or be present with another human being in her time of need. Again, how you can be of service can change through your lifespan and across situations.

You can use the concept of opt for the Greater Good to find motivation to engage in ERP: For example, using purpose might sound like, “I want to do this ERP exercise because that will make me stronger and more likely to be the mom I want to be to my children.” Using service might sound like, “I want to do this ERP exercise because it will trigger my OCD and I’ll be able to work through this challenge so I can teach my kids how to cope with discomfort well.” Opting for the Greater Good as part of your motivation to do ERP takes the focus off of anxiety reduction and places it firmly on the bigger picture. It’s not just about wanting to get over your specific OCD fear. To find the motivation for the hard work of ERP, you need more at stake than just comfort. Remember your sense of purpose and the service you offer others; this can be the prize you seek. Without opting for Greater Good, it’s like planning a trip without knowing your destination or your reason for traveling. If you don’t know where and why you’re going, how will you ever get there?

You Already Yield to Uncertainty

OCD loves certainty. In fact, it demands you seek 100-percent certainty about all of its content, and it thrives off of your every attempt to do so. This is a powerful leverage point for OCD, because it’s impossible to achieve certainty about much of anything (other than the very uplifting thought that everyone is going to die someday…um, probably). And OCD keeps you running in circles on the assumption that you are unwilling to accept uncertainty. But in fact, you gracefully yield to the fact that life is governed by uncertainty most of the time; you just need to realize that you are already flexing a pretty big uncertainty-management muscle. You actually are quite adept at recognizing uncertainty as it approaches and stepping aside when it isn’t about a specific obsession. Thus, the third component of the JOYful attitude is yield to uncertainty.

You Often Give Uncertainty the Right of Way

Is your car or your family’s car parked outside right now? Well, you’re not sure, right? Because unless you are reading this while sitting in the car, it’s in one place and you’re in another. Even if you go out right now to check to see if it’s there, the moment you come back inside, you lose the 100-percent certainty of where it is. And please note that a car is worth a whole lot of money, and you’re just leaving this metallic pile of cash sitting somewhere without actually knowing it’s there, and you are handling that just fine!

Now consider this even more impressive example of your uncertainty-management muscle: do you know where your loved ones are right now? Aha! I bet you actually don’t, unless they’re sitting next to you watching you read this book. You think they are at school, work, home, and so on. But in truth, you actually don’t know (Grayson 2010). And even though you love these people more than anyone, you are managing the uncertainty about their whereabouts with style and grace, yielding to the fact that you have no control over them or what happens to them, and being okay with that.

Another way to look at all of this is to consider that a part of your brain is responsible for saying “good enough” and accepting uncertainty so you can move on. You enter a room, your brain does a hyperspeed assessment of whether the ceiling is going to fall on your head, and it concludes, “Technically it could; no reason to think it will; come in and have a seat.” This happens behind the scenes without your noticing. But what if that part of your brain sputtered or got stalled from time to time? What if you walked into a room and for no discernible reason felt unsure about the stability of the ceiling? It would completely change your perspective and sense of responsibility. When we are struggling to accept uncertainty, it doesn’t necessarily mean we are doing anything wrong ourselves. It’s just that the part of our brain that makes it easy just isn’t working in that moment (recall from the previous chapter that thinking mindfully about OCD includes recognizing that you have a biological disorder). We then have to assume responsibility for the brain’s misfire by volunteering to accept uncertainty.

This is no easy feat—to voluntarily do what we think should be done automatically. Most of the time you are doing ERP without even knowing it. Every day, you walk away from your loved ones and possessions, and you do it without a second thought. How do you do that? By unknowingly yielding to uncertainty and its sidekick, lack of control. You do so very well about 95 to 99 percent of the time—and about the things that matter most. The other 1 to 5 percent of the time, you’re dealing with OCD content (the words it’s using to scare you), and OCD is blocking the “good enough” mechanism, so of course you may not be yielding to uncertainty as well during that time. So the final part of our JOYful attitude is becoming conscious that overall you are already great at yielding to uncertainty. Let this be your secret weapon in your ERP work.

A JOYful Summary

- Jump in: embrace your anxiety and change the dynamic of fear.

- Opt for Greater Good: put your purpose and service to others ahead of doing your compulsions.

- Yield to uncertainty: recognize that you already manage uncertainty really well, and take advantage of this skill.

It’s Game Time

In the pages ahead, we will describe several different ERP games you can play with your OCD. As we mentioned at the top of the chapter, we are describing these exercises as games because toying with your OCD when your OCD is toying with you makes it a fair fight. You can do a better job of living joyfully with OCD by poking it now and then than by always being on the defensive. We recommend you think of this as a mixed bag of tricks, not a treatment manual or guaranteed recipe for success. Not every game in the box will be one that clicks for you and your OCD. Try them out, see what makes your journey a brighter one, and let that shine some light on your life. With each of them, consider how it invites you to jump in to your fear, opt for your Greater Good, and yield to uncertainty.

The “May or May Not” Game

OCD often presents itself in the form of what-if questions. For example, what if I cause someone to become ill because I didn’t wash properly, what if I somehow broke a tenet of my faith, or what if I did something inappropriate earlier? A mindful way to imagine these what-ifs is that they come into your consciousness on a conveyer belt, one after the other, like widgets in a factory. But remember, these are not useful widgets. The OCD wants you to think they are useful, take them off the belt, and validate their usefulness with compulsions, which turns them into OCD weapons that cause you pain. But in this game, you take them off the belt of your mind, repackage them as “may or may not” statements, and then put them back on the belt, where they head to the trash.

So, What if XYZ happens? arrives on the belt. Take it off, repackage it as XYZ may or may not happen, put it back, and send it on its way. Remember, it’s intolerance of uncertainty that stops you in your tracks. By yielding to uncertainty and embracing the feelings that come with it, you can bring your attention back to your purpose, back to your Greater Good. Try it. Consider one of your many what-ifs and practice repackaging it as a “may or may not” statement. Claim ownership of the uncertainty instead of fleeing from it.

Don’t be afraid to add layers to the “may or may not” game as needed. For example, you have just embraced that your fearful thought may or may not be true, and now you’re concerned that your discomfort with this uncertainty will persist. In other words, “What if I feel anxious like this forever?” Great! Take it off the belt, repackage it as “I may or may not feel this way indefinitely,” put it back on the belt, and send it on its way. Further, if the OCD idea contained in the widget was or is at the top of your hierarchy, you may need to play with the repackaged “may or may not” statement repeatedly, saying it over and over, before you can put in back on the belt and watch it successfully head to the trash pile.

Mindfulness is allowing free passage of your thoughts, feelings, and sensations. But OCD can make this difficult, and sometimes you have to attend to some of OCD’s challenges instead of just waving them along. But rather than do compulsion, play games. The OCD presumes you will take the bait with what-if questions. By repackaging them as “may or may not” statements, you throw the OCD a real curve ball.

Changing the Terms of your OCD Contract: The Four Questions Game

When you live with OCD for any length of time, it’s easy to get used to saying you can’t do things or you won’t do things because of the OCD. You may even find yourself telling people, “Oh, my OCD doesn’t let me watch that kind of movie,” or, “I can’t ride public transportation because of my OCD.” You’ve formed a contract with your OCD where it gets to tell you what you can and can’t do, with whom, and when, and presumably you get some relief from pain by agreeing to these terms. But this contract is a disaster. The terms are unreasonable. And anyway, OCD doesn’t even abide by them. You do your compulsions, your life becomes unmanageable, and you still have to live in fear and at odds with uncertainty. The Four Questions game allows you to renegotiate the terms and write a new contract. All you have to do is answer four questions and answer them honestly.

Your New Contract

Question 1: What changes am I going to make from this point forward? Here you want to specifically detail what compulsions you are planning to stop, or what things you are going to stop getting reassurance about, stop reviewing, or stop avoiding.

Example: I am going to start shaking hands with people, even if I think one of us has a cut, and I am not going to use hand sanitizer afterward.

Question 2: What feared outcome is the OCD using to threaten me—that is, what might happen if I make this change? This part can be a bit scary, but try to describe specifically what the OCD says could happen if you made the above changes. Only use uncertainty language here (could, may or may not, might, and so on, not “will”).

Example: I might get a blood-borne illness, which could be serious, and I might have to get treated for it. It might make me a burden to my family and people might think I did something immoral to get sick.

Question 3: What is likely to happen if I continue to obey my OCD and don’t make any changes? Here you want to describe what it would look like if OCD said “jump” and you said “how high?” Don’t hold back. Paint a detailed picture of your life with OCD completely out of control. You can use “certainty” language here (such as “will” or “going to”).

Example: If I continue to avoid shaking hands and keep using hand sanitizer, my fear of disease will keep getting worse, I’ll have chapped and cracked (and probably bleeding) hands, and I’ll end up avoiding important social and business interactions. I will not be able to work anymore and will become a terrible burden on my family.

Question 4: What is my purpose and Greater Good (remember the O of J-O-Y, Opt for the Greater Good), such that I am willing to make these changes and defy my OCD? Describe your values and traits that make it clear you deserve to get better and have the drive to stand up to your OCD.

Example: I am actually a really social person who likes meeting new people, and I am good at my job and deserve to be able to interact with my coworkers. I want to shake hands, because that’s really the kind of person I am. If I make these changes, I will be able to help more people in my work and spend more time being present for my children.

A good way to construct this it to take the answers and assemble them in a paragraph. So the “contract” reads, “I am going to… By doing this, it may or may not cause… If I continue to obey my OCD, it likely will cause… I am committing to these changes because…” You can use this format for any type of compulsive behavior you want to free yourself from. This example is brief, but you can expand your answers to include multiple compulsions, multiple feared consequences, a clear image of what life under the boot of OCD really would look like, and an exploration of your values and dreams. The point is to articulate a vision of reality wherein you are more afraid of letting your OCD run the show than you are of risking whatever it is your OCD is going on about. Read the contract first thing in the morning to get off on the right foot; read it occasionally throughout the day to keep it fresh in your mind. Write it in such a way that after each reading, your number one priority is to resist compulsions.

Getting in the Ring with ERP Scripts

Scripts (also called imaginal exposures) are a form of ERP in which you write out an extended narrative describing your obsessive fears coming true, or describing something that generates the associated feelings, so you can practice being in the presence of your fear without doing compulsions. There are several different ways to write these scripts, so don’t be thrown by variations in style that you may note across OCD workbooks like The Mindfulness Workbook for OCD (Hershfield and Corboy 2013), Freedom from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (Grayson 2014), or The Imp of the Mind (Baer 2002). How you write a script is less important than what a script brings up for you.

As we stated earlier, ERP and mindfulness share a common space in which you welcome what the mind is offering and choose to stay with it instead of pushing it away with compulsions. A good script is a way to do just that: make contact with the internal experience of your fear and make space for it as you would for any other internal experience.

To think about ERP scripts as a game, think of writing out your fear as if it were true and as if the consequences were something you have to cope with as analogous to getting in the boxing ring with OCD. But rather than punching and jabbing your way out, you are going to let it knock you around a bit. The way to win this game is to learn how to take a punch. Since this book is mostly about brief exercises, here’s a template for doing a short-form script. Try answering these questions:

- What happened, is happening, or will happen? Try to speak in the voice of the OCD. Even though what you are afraid of may or may not be true, you fear that it is. Instead of writing My OCD says or I am afraid that, write This is… For example, I hit someone with my car earlier when I thought I was going over a speed bump. You are not trying to convince yourself that these statements are actually true. You are doing a mindfulness exercise of voicing the thought that goes through your head, exactly as the OCD presents it.

- What is the immediate consequence of this? Express the idea that because your fear is true, something unwanted is coming next. Aim to both keep the OCD thought close and generate the associated emotions. Again, stay with the internal experience that drives your compulsive urges. For example, Because I didn’t go back to check, the police will find the body, trace it back to me, and arrest me for vehicular manslaughter.

- What is the long-term consequence? Lastly, to really jump in with the OCD fear, consider what life will look like with the above being true. Don’t abandon the script by ending the story too abruptly (for example, with suicide or just saying nobody will like you). Try to write something that implies an indefinite struggle. For example, I will go to prison, lose my job, my family will stop visiting me after several years, and my time will be spent lamenting my crime.

This short-form script needn’t take more than a paragraph or a few minutes of your time. Caution: don’t do this script at the height of an OCD spike or right after you’ve been triggered, since this type of exposure can actually function as a compulsion if done with the intention of scaring the thought away. Instead, pick a time when you are relatively at ease, and jump in the ring with OCD just to make that contact, flex your OCD fighting muscles, and stretch your mindfulness abilities. In addition, if scripts primarily make you depressed (as opposed to primarily making you anxious), we recommend that you emphasize uncertainty-focused scripts (“may or may not”), discussed earlier.

The “Throw Open the Gates” Game

OCD sufferers who deal with moral, violent, and sexual obsessions often feel like their unwanted thoughts are violating sacred mind space. It is as if there is a fence around the mind, protecting it from intruders, and this fence has a gate that’s damaged, allowing the unwanted thoughts to slip through and cause havoc. When your OCD is in high gear, it may feel like there is no gate at all. If you suffer from these types of obsessions, you likely try to avoid or neutralize these upsetting thoughts with mental rituals and reassurance seeking.

When people with OCD get surprised by the sudden and intense horribleness of the content of their thoughts, they are more likely to react to those thoughts instead of approaching them with mindfulness. It’s the equivalent of thinking you’re playing a harmless game of Super Mario Bros. and then suddenly realizing you’re playing Grand Theft Auto and just ran over someone with a stolen car. The shock of the OCD content throws you, and you respond compulsively in a state of disorientation, not careful contemplation. So eliminating the element of surprise is an important tool in fighting these types of obsessions.

Remember, in ERP we purposely bring our fears to mind and practice resisting compulsions. This teaches us not only that we can jump in and even want anxiety and embrace uncertainty, but also that we are very much more in command of our minds than we give ourselves credit for. Though we cannot pick and choose what thoughts come asking for our attention, we can influence our attention to stay with or return to the objects of our choosing. In short, practicing bringing on the unwanted thoughts intentionally, as part of an ERP exercise, eliminates the element of surprise. The OCD may lob criticism and guilt your way for purposely having this or that thought, but it loses the shock-and-awe effect of putting the thoughts there against your will. Playing this game is a great way to stick it to the OCD and practice maintenance of any ERP gains you’ve already made. You can practice getting out in front of the triggering thoughts in a number of ways; here are some ideas:

- Step One: Go to a public place, such as a shopping mall, where you are likely to encounter a steady stream of people you don’t know.

- Step Two: Tell yourself that for the next period of time (anywhere from one to fifteen minutes), you are going to open the gate in your mind and invite your unwanted thoughts to come in.

- Step Three: Wander around the public place and look at different people. As you set eyes on each person, apply your unwanted thoughts in their direction. For example, if you have harm OCD, picture different ways of harming people willingly. In other words, hand out your worst obsessive thoughts like flyers to anyone who passes by your field of vision. If you have sexual obsessions, apply the same logic. Purposely go ahead and think your unwanted sexual thoughts about this person, that person…nobody escapes your attention during this ERP game. For those with religious restrictions that may make purposefully manufacturing these types of thoughts more challenging, it may be a good idea to consult with your clergy before attempting this game; see if there is a way to do so without overtly violating the tenets of your faith. In most faith traditions, flexibility in this area for mental health purposes is allowed and encouraged.

- Step Four: Once you’ve assaulted everyone in your path (mentally of course), and the time you’ve determined appropriate for this heavy lifting has ended, stop. Thoughts may continue to come, but stop willing them in intentionally. In other words, stop driving the train, though the train may keep moving for a bit. This would be a good time to access a self-compassionate coping statement (see chapter 2) and congratulate yourself on a good ERP workout.

Testing Is the Only Way to Fail

For this ERP game to work, you absolutely must commit to a policy of non-checking and non-judging. If you use this game to test your reactions and self-reassure, it only emboldens the OCD. Remember, exposures are acts of mindfulness, so you are bringing the thoughts to the forefront of your mind (exposure) and responding with no resistance, no suppression, and no attempt to reassure or neutralize (response prevention). For this ERP game to work, you have to dive in, expose to your unwanted thoughts with reckless abandon, and commit to experiencing whatever that is like without the deceiving illusion of safety you would get from compulsions.

The Trigger “Scavenger Hunt” Game

Many people with OCD avoid activities not because the activity itself is triggering, but because the activity requires being in a place where triggers may be present. For example, even without a fear of flying, your OCD may tell you to avoid traveling because of all the triggers you might encounter at the airport. Mastering OCD is a process of reclaiming what you lost to the disorder before you knew how to stand up to it, so exposures that emphasize getting out there and engaging with the world can be particularly meaningful.

In this game, the emphasis is again on getting out in front of your triggers rather than letting them sucker punch you. Since you may already have good insight into where your triggers may come up, seeking them out and counting or collecting them takes the power away from OCD and puts it in your hands. For example, if your OCD tells you that you might push people into the street if you walk too close to them on the sidewalk, start by walking down the block and letting yourself observe people as you pass each other. When your OCD says, “You might push that person,” say, “That’s one.” In other words, collect your triggers like Pokemon, one after the other. Another person passes by, and your anxiety spikes with the thought of harming them… “That’s two.”

Or you might collect noticing physical triggers. For instance, say your OCD is afraid of bandages because it doesn’t like that they come in contact with blood, or cigarettes butts because they were in someone’s mouth and could have germs or carry some disease. Go to a public place where lots of people congregate, and then purposely seek out used bandages and cigarette butts on the sidewalk and the anxiety and intrusive thoughts they create. Keep track every time you see one of your triggers. See how many of these triggers you can collect.

This exercise is less about trying to expose to distress and more about practicing your skill of mentally noting things as they pass. If you can count your breath, you can count your triggers. To “game-ify” it, you can practice with points. Each trigger is worth a point, and you may set out to collect ten, for example. Have fun with the process, giving yourself bonus points for kooky things, like finding a bandage featuring a cartoon character. This game strengthens your ability to not only receive unwanted thoughts, but also gently tap them as they go by without attaching judgment or compulsive analysis to them.

Take a Hike, OCD! a.k.a. Exercise, the Exercise

Exercise, healthy eating, and other good habits make living with any chronic condition easier. But physical exercise and ERP can both be very time-consuming. Why not combine the two? The following is an exercise specifically for strengthening your ability to let go of mental rituals and improve control over your attention.

Pick a physical activity that requires some effort and time commitment; for example, climbing a big hill, running, or biking for half an hour or more. During the first half of that activity, try to obsess as hard as you can. By “obsess” we mean devote as much attention as you can to your unwanted thoughts. You can do this with agreeing statements (as in scripts in which you would describe your fears as being true) or you can do this with “may or may not” statements (describing your fears as potentially true). The point is, try to make your unwanted thoughts the anchor of your attention.

Once you have the unwanted thoughts locked in, engage in your physical activity. Hold the unwanted thoughts in this way without any self-reassurance or attempts to increase certainty, and do so for the first half of your exercise (that is, if you are on a twenty-minute hike, do this for the first ten minutes of the hike). When the time has elapsed and you are at the halfway point in your physical exercise, abruptly stop the emphasis on exposure and switch the emphasis to another anchor. In other words, release your tight grip on the obsession and grip tightly to another area of focus. This new anchor can be music, an audio book, or some other pleasant distraction (bring headphones). Ideally it should be something that makes it difficult to focus on your unwanted thought at the same time.

Over time, this practice of bringing on the obsession with intensity during one activity (the first half of your physical exercise), then dropping the obsession for another activity (the second half), can help you develop a sense of confidence that attachment to an obsession does not necessitate mental rituals. You can engage with them and disengage from them without compulsions. Turning the volume of your unwanted thoughts up really loud, then turning the volume off, demonstrates that you have some access to the volume knob in the first place.

Breaking the News Game, a.k.a. Headlines

Humor is an excellent way to deal with OCD, because it takes some of the sting out of the OCD content without relying on compulsive reassurance or other rituals. In fact, using humor is a good way to help you to stay with an unwanted thought without doing rituals. By doing so, you are not triggering the negative reinforcement loop described in the introduction; instead, you are teaching your brain that you can handle these thoughts and that rituals are a waste of energy.

This game is all about using your natural predisposition toward creativity to out-silly your OCD’s silly ideas. The game is simple—make a newspaper headline and subheading about your OCD thoughts. A good way to construct a headline is to say what the OCD is threatening you with in the most blunt way possible; then create a subheading that articulates how you are failing to do what the OCD says you need to do about it.

- “AREA WOMAN IDENTIFIED AS WORST PERSON EVER: Failure To Check Locks Results In Entire House Being Stolen (Including All The People In It, Who Are Still Missing).”

- “LOCAL MAN ACQUIRES VIRUS THAT WIPES OUT EASTERN SEABOARD: Should Have Taken Second Coffee Cozy From The Stack.”

- “ASYMMETRICAL TABLE SETTING ALTERS POLARITY OF THE EARTH: Billions of People Sent Into Orbit Because Bob Is Too Lazy To Move His Fork.”

This is a game you can also play with others as you collaborate on the goofiest The Onion-style headlines for your common triggers. It can be used as a stand-alone practice to strengthen your humor response or as a direct response in the moment a trigger occurs.

The Halfway There Game

OCD does not like things to be done halfway. OCD is black or white, all or nothing, good or bad. To do something halfway feels just…wrong, or as if it could cause something catastrophic to happen in its wake. So this game is simple. Think of something you’d normally do all the way, and then just do part of it. And don’t apologize or confess for having done it only halfway—owning the incompleteness is part of the game! For extra points, do things almost all the way, but not quite. Some examples:

- Buy only some of the items on your grocery list.

- Leave out details in a story you are recounting.

- Fast-forward through five minutes of the show you’re binge watching on Netflix.

- Clean everything in the bathroom except for the sink, or vacuum everything but a noticeably dirty section of the carpet.

- Don’t seal every opening on that cardboard box you are mailing to your cousin (admit it, your packages are taped so well that you’d need a Ginsu knife to get them open).

- Buy seven place settings instead of eight or ten.

- Say only part of a prayer.

- Ride the stationary bike for twenty-nine minutes.

This game has infinite JOYful possibilities for bugging your OCD. More importantly, this game functions as a healthy way to practice sticking it to the OCD. It’s a way to build your stamina against OCD, walking that extra block instead of taking the train. Every bit counts.

It Is Harder Than You Think, But You Are Stronger Than You Know

In clinical practice we are often asked whether the experience of ERP is supposed to feel the way it feels. Many of our clients are so used to pushing the lid down on the pressure cooker with compulsions that their attempts at ERP are met with a blast of scalding mental steam. People with OCD are especially prone to emotional reasoning—that is, believing ideas to be true because they may feel true at the time. So when the pain of doing compulsions is shifted to the pain of doing exposure in treatment, it’s very common not only to think, “This is too hard” but also “This is too hard for a reason!” What could the reason be?

- My fears are actually going to come true, and the feelings are the final warning.

- I’m doing ERP wrong; the feeling shouldn’t be this intense.

- I’m untreatable.

- It’s just actually this hard.

Suspense killing you? The answer is #4. At the core of understanding how to master OCD is understanding that the only way out of pain is through it. Avoidance is running from pain so that it chases you down. Compulsions (mental or physical) are strategies for sidestepping or jumping over the pain. But only leaning in or jumping in to it gets you through to the other side. The pain of ERP is almost always going to seem more threatening than expected, especially right before jumping in, as you anticipate the exercise. But your tolerance for this pain extends far beyond what your OCD would have you believe.

This secret truth is one to cherish throughout your treatment journey. We are all stronger than we give ourselves credit for. We are the ones with the credit to give, and there are no limitations on our doing so. So if we can carry both of these concepts in our hearts—that ERP being harder than we might expect is just how ERP works, and that our capacity for standing up to the pain of OCD is greater than we are likely to assume—nothing can stand in our way.

Bringing It Home

In this chapter we described a quick way to remember your motivations and intent in ERP, using the mnemonic J-O-Y. This stands for Jump in (meaning embrace your anxiety), Opt for the Greater Good (meaning focus on your values beyond anxiety reduction), and Yield to uncertainty (meaning let yourself be unsure about your OCD content). We then offered up a list of ERP games or strategies for playfully engaging with the OCD, using exposure and mindfulness techniques, aimed at helping you stay on top of your management of the disorder. You are as entitled to live joyfully as anyone else, and we hope incorporating these tools in your journey helps bring you some J-O-Y. In the chapters ahead, we will explore different facets of long-term mastery over OCD.