I’ve come to see institutional decline like a staged disease: harder to detect but easier to cure in the early stages, easier to detect but harder to cure in the later stages. An institution can look strong on the outside but already be sick on the inside, dangerously on the cusp of a precipitous fall.

In the autumn of 2004, I received a phone call from Frances Hesselbein, founding president of the Leader to Leader Institute. “The Conference Board and the Leader to Leader Institute would like you to come to West Point to lead a discussion with some great students,” she said.

“And who will be the students?” I asked, envisioning perhaps a group of cadets.

“Twelve U.S. Army generals, twelve CEOs, and twelve social sector leaders,” explained Frances. “They’ll be sitting in groups of six, two from each sector—military, business, social—and they’ll really want to dialogue about the topic.”

“And what’s the topic?”

“Oh, it’s a good one. I think you’ll really like it.” She paused. “America.”

America? I wondered, What could I possibly teach this esteemed group about America? Then I remembered what one of my mentors, Bill Lazier, told me about effective teaching: don’t try to come up with the right answers; focus on coming up with good questions.

I pondered and puzzled and finally settled upon, Is America renewing its greatness, or is America dangerously on the cusp of falling from great to good?

While I intended the question to be simply rhetorical (I believe that America carries a responsibility to continuously renew itself, and it has met that responsibility throughout its history), the West Point gathering nonetheless erupted into an intense debate. Half argued that America stood as strong as ever, while the other half contended that America teetered on the edge of decline. History shows, repeatedly, that the mighty can fall. The Egyptian Old Kingdom, the Minoans of Crete, the Chou Dynasty, the Hittite Empire, the Mayan Civilization—all fell.1 Athens fell. Rome fell. Even Britain, which stood a century before as a global superpower, saw its position erode. Is that America’s fate? Or will America always find a way to meet Lincoln’s challenge to be the last best hope of Earth?

At a break, the chief executive of one of America’s most successful companies pulled me aside. “I find our discussion fascinating, but I’ve been thinking about your question in the context of my company all morning,” he mused. “We’ve had tremendous success in recent years, and I worry about that. And so, what I want to know is, How would you know?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“When you are at the top of the world, the most powerful nation on Earth, the most successful company in your industry, the best player in your game, your very power and success might cover up the fact that you’re already on the path to decline. So, how would you know?”

The question—How would you know?—captured my imagination and became part of the inspiration for this piece. At our research laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, we’d already been discussing the possibility of a project on corporate decline, spurred in part by the fact that some of the great companies we’d profiled in the books Good to Great and Built to Last had subsequently lost their positions of excellence. On one level, this fact didn’t cause much angst; just because a company falls doesn’t invalidate what we can learn by studying that company when it was at its historical best. (See the sidebar for an explanation.) But on another level, I found myself becoming increasingly curious: How do the mighty fall? If some of the greatest companies in history can collapse from iconic to irrelevant, what might we learn by studying their demise, and how can others avoid their fate?

I returned from West Point inspired to turn idle curiosity into an active quest. Might it be possible to detect decline early and reverse course, or even better, might we be able to practice preventive medicine? I began to think of decline as analogous to a disease, perhaps like cancer, that can grow on the inside while you still look strong and healthy on the outside. It’s not a perfect analogy; as we’ll see later, organizational decline, unlike cancer, is largely self-inflicted. Still, the disease analogy might be helpful. Allow me to share a personal story to illustrate.

On a cloudless August day in 2002, my wife, Joanne, and I set out to run the long uphill haul to Electric Pass, outside Aspen, Colorado, which starts at an altitude of about 9,800 feet and ends above 13,000 feet. At about 11,000 feet, I capitulated to the thin air and slowed to a walk, while Joanne continued her uphill assault. As I emerged from tree line, where thin air limits vegetation to scruffy shrubs and hardy mountain flowers, I spotted her far ahead in a bright-red sweatshirt, running from switchback to switchback toward the summit ridge. Two months later, she received a diagnosis that would lead to two mastectomies. I realized, in retrospect, that at the very moment she looked like the picture of health pounding her way up Electric Pass, she must have already been carrying the carcinoma. That image of Joanne, looking healthy yet already sick, stuck in my mind and gave me a metaphor.

We’ll turn shortly to the research that bore this idea out, but first let’s delve into a terrifying case, the rise and fall of one of the most storied companies in American business history.

WHY THE FALL OF PREVIOUSLY GREAT COMPANIES DOES NOT NEGATE PRIOR RESEARCH

The principles we uncovered in prior research do not depend upon the current strength or struggles of the specific companies we studied. Think of it this way: if we studied healthy people in contrast to unhealthy people, and we derived health-enhancing principles such as sound sleep, balanced diet, and moderate exercise, would it undermine these principles if some of our previously healthy subjects started sleeping badly, eating poorly, and not exercising? Clearly, sleep, diet, and exercise would still hold up as principles of health.

Or consider this second analogy: suppose we studied the UCLA basketball dynasty of the 1960s and 1970s, which won ten NCAA championships in twelve years under coach John Wooden.2 Also suppose that we compared Wooden’s UCLA Bruins to a team at a similar school that failed to become a great dynasty during the exact same era, and that we repeated this matched-pair analysis across a range of sports teams to develop a framework of principles correlated with building a dynasty. If the UCLA basketball team were to later veer from the principles exemplified by Wooden and fail to deliver championship results on par with those achieved during the Wooden dynasty, would this fact negate the distinguishing principles of performance exemplified by the Bruins under Wooden?

Similarly, the principles in Good to Great were derived primarily from studying specific periods in history when the good-to-great companies showed a substantial transformation into an era of superior performance that lasted fifteen years. The research did not attempt to predict which companies would remain great after their fifteen-year run. Indeed, as this work shows, even the mightiest of companies can self-destruct.

ON THE CUSP, AND UNAWARE

At 5:12 a.m. on April 18, 1906, Amadeo Peter Giannini felt an odd sensation, then a violent one, a slight, almost imperceptible shift in his surroundings coupled with a distant rumble like faraway thunder or a train.3 Pause. One second. Two seconds. Then—bang!—his house in San Mateo, California, began to pitch and shake, to, fro, up, and down. Seventeen miles north in San Francisco, the ground liquefied underneath hundreds of buildings, while heaving spasms under more solid ground catapulted stones and facades into the streets. Walls collapsed. Gas mains exploded. Fires erupted.

Determined to find out what had happened to his fledgling company, the Bank of Italy, Giannini endured a six-hour odyssey, navigating his way into the city by train and then by foot while people streamed in the opposite direction, fleeing the conflagration. Fires swept toward his offices, and Giannini had to rescue all the imperiled cash sitting in the bank. But criminals roamed through the rubble, prompting the mayor to issue a terse proclamation: “Officers have been authorized by me to KILL any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime.” With the help of two employees, Giannini hid the cash under crates of oranges on two commandeered produce wagons and made a nighttime journey back to San Mateo, where he hid the money in his fireplace. Giannini returned to San Francisco the next morning and found himself at odds with other bankers who wanted to impose up to a six-month moratorium on lending. His response: putting a plank across two barrels right in the middle of a busy pier and opening for business the very next day. “We are going to rebuild San Francisco,” he proclaimed.4

Giannini lent to the little guy when the little guy needed it most. In return, the little guy made deposits at Giannini’s bank. As San Francisco moved from chaos to order, from order to growth, from growth to prosperity, Giannini lent more to the little guy, and the little guy banked even more with Giannini. The bank gained momentum, little guy by little guy, loan by loan, deposit by deposit, branch by branch, across California, renaming itself Bank of America along the way. In October 1945, it became the largest commercial bank in the world, overtaking the venerable Chase National Bank.5 (Note of clarification: in 1998, NationsBank acquired Bank of America and took the name; the Bank of America described here is a different company than NationsBank.)

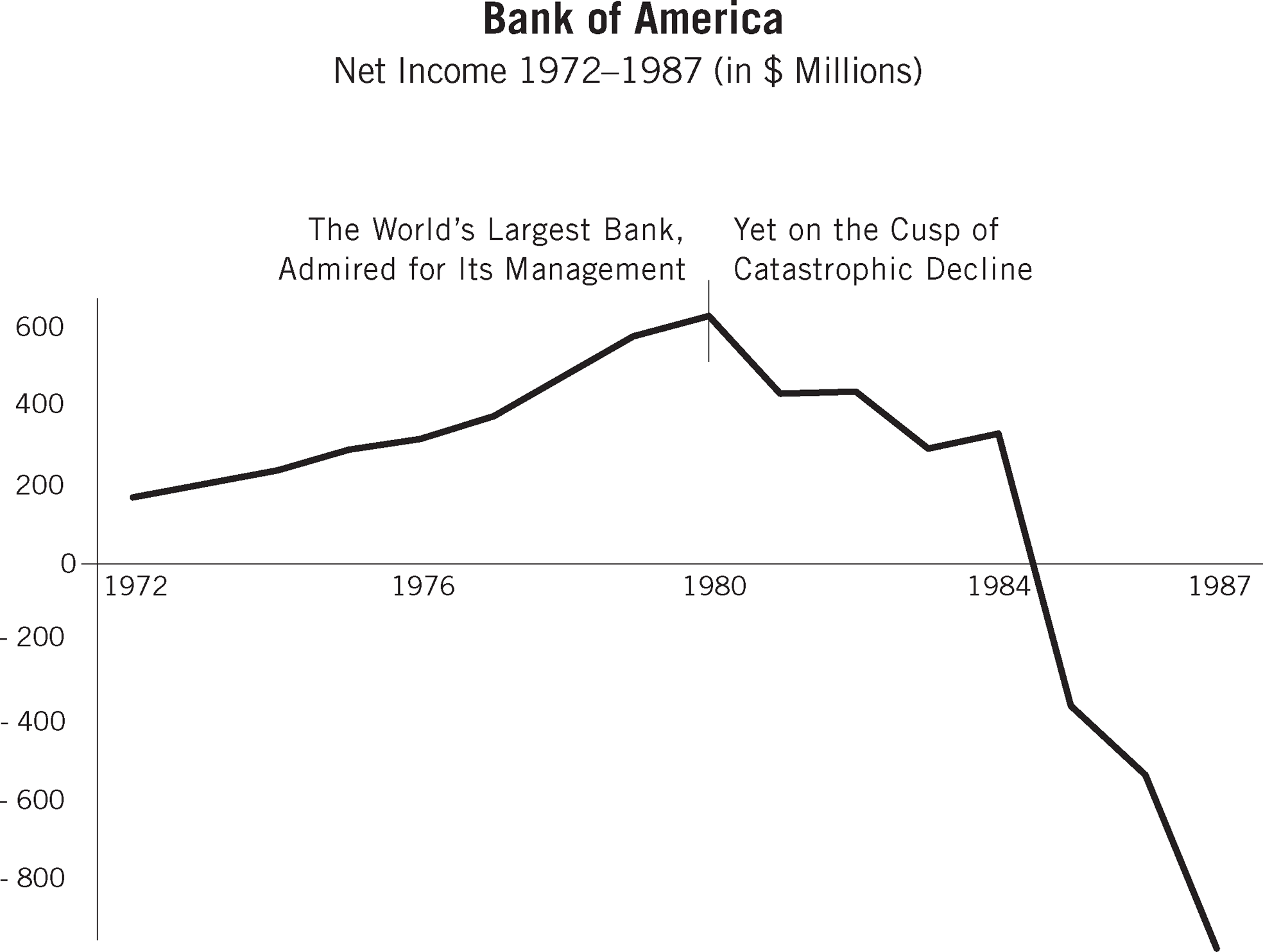

Over the next three decades, Bank of America gained a reputation as one of the best managed corporations in America.6 An article in the January 1980 issue of Harvard Business Review opened with a simple summary: “The Bank of America is perhaps best known for its size—it is the world’s largest bank, with nearly 1,100 branches, operations in more than 100 countries, and total assets of about $100 billion. In the opinion of many close observers, an equally notable achievement is its quality of management . . .”7

Were anyone to have predicted in 1980 that in just eight years Bank of America would not only fall from its acclaimed position as one of the most successful companies in the world, but would also post some of the biggest losses in U.S. banking history, rattle the financial markets to the point of briefly depressing the U.S. dollar, watch its cumulative stock performance fall more than 80 percent behind the general stock market, face a serious takeover threat from a rival California bank, cut its dividend for the first time in fifty-three years, sell off its corporate headquarters to help meet capital requirements, see the last Giannini family board member resign in outrage, oust its CEO, bring a former CEO out of retirement to save the company, and endure a barrage of critical articles in the business press with titles like “The Incredible Shrinking Bank” and “Better Stewards (Corporate and Otherwise) Went Down on the Titanic”—were anyone to have even suggested this outcome—he or she would have been viewed as a pessimistic outlier. Yet that’s exactly what happened to Bank of America.8

If a company as powerful and well positioned as Bank of America in the late 1970s can fall so far, so hard, so quickly, then any company can fall. If companies like Motorola and Circuit City—icons that had once served as paragons of excellence—can succumb to the downward forces of gravity, then no one is immune. If companies like Zenith and A&P, once the unquestioned champions in their fields, can plummet from great to irrelevant, then we should be wary about our own success.

Every institution is vulnerable, no matter how great. No matter how much you’ve achieved, no matter how far you’ve gone, no matter how much power you’ve garnered, you are vulnerable to decline. There is no law of nature that the most powerful will inevitably remain at the top. Anyone can fall and most eventually do.

I can imagine people reading this and thinking, “Oh my goodness—we’ve got to change! We’ve got to do something bold, innovative, and visionary! We’ve got to get going and not let this happen to us!”

Not so fast!

In December 1980, Bank of America surprised the world with its new CEO pick. Forbes magazine described the process as “rather like choosing a new pope,” the twenty-six directors huddled behind closed doors like cardinals in conclave.9 You might think that Bank of America ultimately fell because they ended up crowning a fifty-something gentleman, a faceless bureaucrat and banker’s banker who couldn’t change with the times, couldn’t lead with vision, couldn’t make bold moves, couldn’t seek new businesses and new markets.

But in fact, the board picked a vigorous, forty-one-year-old, tall, articulate, and handsome leader who told the Wall Street Journal that he believed the bank needed a “good kick in the fanny.” Seven months after taking office, Samuel Armacost bought discount brokerage Charles Schwab, an aggressive move that pushed the edges of the Glass-Steagall Act and energized Bank of America with not only a new business, but also a cadre of irreverent entrepreneurs. Then he engineered the largest interstate banking acquisition to date in the nation’s history, buying Seattle-based Seafirst Corp. He launched a $100 million crash program to blast past competitors in ATMs, allowing the bank to leap from being a laggard to boasting the largest network of ATMs in California. “We no longer have the luxury of sitting back to learn from others’ mistakes before we decide on what we will do,” he admonished his managers. “Let others learn from us.” Here, finally, Bank of America had a leader.10

Armacost ripped apart outmoded traditions, closed branches, and ended lifetime employment. He instituted more incentive compensation. “We’re trying to drive a wedge between our top performers and our nonperformers,” noted one executive about the new culture.11 He allowed Schwab’s leaders to continue their practice of leasing BMWs, Porsches, and even a Jaguar, irritating traditional bankers limited to more traditional Fords, Buicks, and Chevrolets.12 He hired a high-profile change consultant and shepherded people through a transformation process that BusinessWeek likened to a religious conversion (describing the bank as “born again”) and that the Wall Street Journal depicted as “its own version of Mao’s Cultural Revolution.”13 Proclaimed Armacost, “No other financial institution has had this much change.”14 And yet, despite all this leadership, all this change, all this bold action, Bank of America fell from its net income peak of more than $600 million into a decline that culminated from 1985 to 1987 with some of the largest losses up to that point in banking history.

To be fair to Mr. Armacost, Bank of America was already poised for a downward turn before he became CEO.* My point is not to malign Armacost, but to show how Bank of America took a spectacular fall despite his revolutionary fervor. Clearly, the solution to decline lies not in the simple bromide “Change or Die”; Bank of America changed a lot, and nearly killed itself in the process. We need a more nuanced understanding of how decline happens, which brings us to the five stages of decline that we uncovered in our research project.

* For an excellent account, see Gary Hector’s well-written and authoritative book, Breaking the Bank: The Decline of BankAmerica.