Figure 6.1

Stakeholder map for food and wine festivals

Chapter 6

Food and Wine Festivals: Stakeholders, Long-Term Outcomes and Strategies for Success

Let the progress of the meal be slow, for dinner is the last business of the day; and let the guests conduct themselves like travellers due to reach their destination together.

Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste, 1825

Destinations around the world have adopted an events strategy to assist in their economic and tourism development world (see, for example, Dubai (Anwar, 2004), Melbourne (Hede and Jago, 2005) or Edinburgh). As such, many events are at least in part financially supported by government funding, foregrounding the need to implement government policy. Under these circumstances, it can become a political imperative for events to deliver not only positive economic, but also positive social and environmental outcomes for their host communities. While such an imperative directly impacts those events that are financially supported by governments, it also places considerable demands on the rest of the event sector to enhance the outcomes of events for their host communities, both in the short and long term.

In the context of this trend, the management of events has become an increasingly complex task. The range of event stakeholders and the short- and long-term expectations they have of their associations with events are often diverse. Few events have escaped the impact of this trend; food and wine festivals, which are the focus of this chapter, are no exception. The primary aim of any food and wine festival is to enhance the sustainability of its key stakeholder industries, namely the hospitality, food and wine industries. As a minimum, a well-managed food and wine festival should be able to achieve a range of short-term outcomes for these stakeholders such as:

Promoters and managers of food and wine festivals should, however, be aiming to develop a number of longer-term benefits resulting from food and wine festivals, such as:

By achieving some of these longer-term outcomes, food and wine festivals thus enhance their own sustainability. Their achievement, however, is not an easy task; strategies need to be developed and implemented to achieve the desired outcomes. It becomes very important, therefore, that food and wine festivals work collaboratively with their extensive range of stakeholders – particularly the hospitality, food and wine industries – to identify what long-term benefits are desired and how they may be achieved through a food and wine festival.

This chapter examines the ways in which food and wine festivals can collaborate with their stakeholders to produce some long-term benefits. First, the chapter identifies the stakeholders of food and wine festivals and explores their expectations of their association with a food and wine festival. The chapter then focuses on the hospitality, food and wine industries, which are considered to be the key stakeholders for food and wine festivals, and examines the short- and long-term outcomes they desire from their association with a food and wine festival. The chapter explores the strategies that might be used to achieve those longer-term objectives which, as to be expected, are not as easy to implement or achieve as some of the shorter-term goals. Case study material of the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival in Australia is interspersed throughout the chapter to illuminate the ways in which stakeholder objectives might be achieved, and to highlight best practice in the burgeoning event sector.

Food and Wine Festivals: Stakeholders and their Expectations

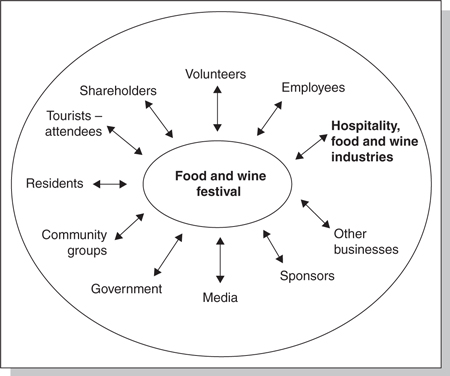

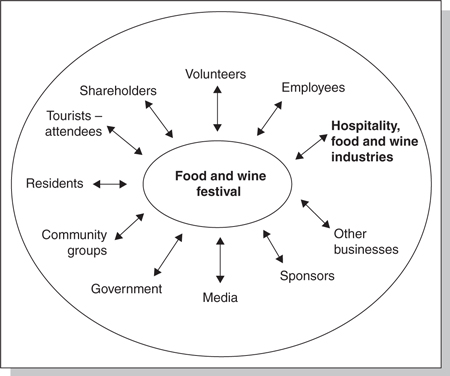

Stakeholders, or constituents, are defined as those groups or individuals who can affect, or are affected by, the achievement of the organization’s objectives (Freeman, 1984). Clarkson (1995) stated that ‘stakeholders are persons or groups that have claim or ownership rights, interests in a corporation and its activities, past present and future’. Food and wine festivals have many stakeholders. Figure 6.1 depicts a generic set of stakeholders for a food and wine festival, highlighting the diversity in the stakeholder network and showing that the stakeholders represent of wide cross-section of the host community. Not all food and wine festivals will have all the stakeholders included in Figure 6.1, but some may have a greater range of stakeholders, which may, for example, be a function of their location.

Figure 6.1

Stakeholder map for food and wine festivals

Undoubtedly, the primary objective of any food and wine festival is to increase the stakeholders’ support (e.g. financial, political, social) for the local hospitality, food and wine industries. By definition, the various stakeholders of a food and wine festival will also be interested in achieving this objective. In reality, however, stakeholders will have their own objectives in relation to their association with a food and wine festival. Indeed, stakeholders will very often have differing, sometimes competing, expectations of their association with a food and wine festival. One challenge for festival organizers is to identify and capitalize on the differences and synergies between the stakeholders, particularly of those of their sponsors, while also capitalizing on their commonalities. Understanding the various stakeholders’ motivations and expectations for their association with the food and wine festival is imperative.

Differences between the various stakeholders’ motivations and expectations are to be expected, but they do impose unique challenges for promoters and managers of food and wine festivals. For example, some sponsors are primarily focused on the exposure they will gain as a result of their association with a food and wine festival. The role and importance of sponsors in the event sector have grown markedly over the past few decades. Sponsors have been found to be concerned with the influence that their association with an event has on their brand equity, which encompasses the heritage of the brand, its logo, the people behind the brand, and the brand’s values and priorities. Sponsors may also be interested in achieving maximum audience/consumer reach through the media exposure they might gain from their endorsement of a food and wine festival. As a stakeholder, the media has different priorities; the media is interested as to whether it will source a story in relation to the festival worthy of public interest, which will increase the readership of its publications (e.g. magazines, book and web sites). It is increasingly apparent, however, that the media and media organizations are sponsoring food and wine festivals themselves; blurring the lines between the role of the media as sponsor and the role of independent reporter.

Governments have become stakeholders of food and wine festivals. Each government’s focus and expectations of a food and wine festival will vary, but will be contingent on the focus of the specific government department funding the food and wine festival. For example, a tourism department will be interested in the economic impacts that such a food and wine festival can produce, whereas an education department will be interested in the educational and training outcomes resulting from a food and wine festival.

On the individual level, attendees of food and wine festivals are motivated to attend food and wine festivals for a range of reasons. In a study exploring the motivations of attendees of a wine festival, Yuan et al., (2005) found that attendees were motivated by different elements of the event’s theme – the synergy of wine, travel and special event. Special event research, across a range of events, indicates that attendees can be motivated to attend events for a number of reasons including novelty-seeking behaviour, curiosity, the need to socialize with family and friends, to be with people who are enjoying themselves, and relaxation (Mohr et al., 1993; Uysal et al., 1993). Charters and Ali-Knight (2002) suggested that the wine tourism experience, which they highlighted is linked with experiences related to food, is most noticeably accessed when wine tourists participate in events and festivals. Experiences at food and wine events and festivals can be highly satisfying for attendees. Indeed, Gorney and Busser (1996) found that attendance at special events generally improved attendees’ satisfaction with life in general.

We tend to think of the individual at the food and wine festivals as the ‘attendee’, or as the ‘consumer’, but there are also volunteers and employees who, functioning as individuals, come to a food and wine festival for their own reasons. Their participation has a number of outcomes for them including the development of social networks and technical and life skills (Fairley et al., 2007). Although much research has focused on volunteers within the context of special events and festivals (see, for example, Elstad, 1996; Saleh and Wood, 1998; Davidson and Carlsen, 2002); little attention has been directed towards the paid employees of events and festivals. Walle (1996), however, noted that participation in some special events becomes a symbol of a performers’ professional status. This notion certainly extends to food and wine festivals, as increasingly cooking demonstrations, expert panels of food and wine critics and public lectures are included on the festival programmes – resulting in industry professionals, including chefs, food and wine authors and critics, being elevated to performer, and sometimes even celebrity status. Indeed, this was the case at the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival in 2007 when a number of chefs, food and wine authors and critics were an integral part of the festival’s programming.

The Melbourne Food and Wine Festival: A Network of Stakeholders

The Melbourne Food and Wine Festival is incorporated as a not-for-profit organization, and derives its funding from both the public and private sectors. The 14-day event is held in March each year. In 2007, the festival celebrated its 15th festival, making it the ‘longest running food and wine festival in the southern hemisphere’ (Melbourne Food and Wine Festival, 2007a). In 2007, over 300,000 people attended 140 ticketed and non-ticketed events. The majority of the events were held in Melbourne, but some were held in regional destinations. Each year, a number of high profile international chefs are invited to attend the festival. One of these, Rose Gray of the River Café in London, stated that ‘we just don’t have festivals like this in London … Melbourne’s food and wine culture, with festival events sprawling over the CBD, is unlike any other in the world’ (Melbourne Food and Wine Festival, 2007b). The ticketed and non-ticketed programme provides an interesting context for analysis as case study, as it highlights how the long-term benefits of a food and wine festival can be enhanced for stakeholders through the active collaboration with the hospitality, food and wine industries.

The Melbourne Food and Wine Festival has been successful in recruiting a number of sponsors, that, despite having a diverse range of objectives in relation to their associations with the festival, appear to have some commonalities among them, particularly with regard to the commitment they have to the festival (Table 6.1) which details the sponsors and their various sectors that they represent. Like many other events and festivals, the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival developed a hierarchy for its corporate stakeholders (i.e. sponsors). For example, in 2007 one of the two local newspapers, The Age, with an average daily readership of approximately 800,000 (The Age, 2007) was the festival’s ‘Presenting Sponsor’. Government partners for the festival were the State of Victoria, Tourism Victoria and the City of Melbourne (the municipality which is host to most of the festival’s events).

Table 6.1 2007 Melbourne Food and Wine Festival: hierarchy of sponsors

As can be seen in Table 6.1, major partners for the festival were local hospitality and/or food organizations, namely Crown (Melbourne’s casino) and Coffex (coffee-maker and distributor), and international hospitality and/or food organizations, namely Miele and Sanpelligrino. These organizations and their products/services were widely used in the festival. The official hotel for the festival was the Langham Hotel, where ticketed events such as a series of MasterClasses were held. Media partners included radio (local government sponsored radio stations on two frequencies, and a privately owned radio station); Delicious: the food magazine (government sponsored food magazine); and a web site design and hosting organization, Morpheum, that has been successful in targeting local government agencies. Four venue partners were the Arts Centre (a government-managed performing arts venue); Southgate (leisure precinct comprised privately owned businesses); Federation Square (Melbourne’s central public space and leisure precinct, which is managed by a state government instrumentality); and the Telstra Dome (a professional sports and leisure venue with corporate facilities). Delaware North Companies, a major contract catering company in Australia and catering provider at the Telstra Dome, was the festival’s venue partner.

The festival’s ‘product partners’, originating from the hospitality and food industries were Phase 5, a supplier of organically produced camellia tea oil; Pura, Australia’s major producer and supplier of dairy products; Equal; and All-Clad, a US-based company specializing in the production of professional-standard cookware. The festival’s ‘wine partners’ were: Wines of Victoria, which operates as a industry body under the auspices of the Victorian Wine Industry Association; and the longtime established Victorian vineyard, Brown Brothers. William Angliss, the tertiary institution that has supplied education and training to the Victorian hospitality, food and wine industries since 1940, was also one of the festival’s sponsors. In addition to the festivals’ official sponsors, in 2007 the festival acknowledged the generosity of a number of hospitality, tourism and leisure organizations, including: the Melbourne Zoo and a number of regional wineries including Voice of the Vine, Coldstream Hills, Yarraloch, Matilda Bay, Montalto and Mirka at Tolarno. Overall, the festival developed a network of sponsors that were able to facilitate achieving the festival’s vision.

The Hospitality, Food and Wine Industries: Key Stakeholders for Achieving Long-Term Outcomes

Food and wine festivals are inextricably linked to the local, and increasingly it seems, to the international hospitality, food and wine industries. While stakeholder theory suggests that all stakeholders are equally important, the relationship a food and wine festival has with the hospitality, food and wine industries is paramount to its success. In an effective relationship, the association between the central organization (i.e. the food and wine festival) and its stakeholders is reciprocal. That is, while a food and wine festival is designed to sustain the hospitality, food and wine industries, it is dependent on them for its own sustainability. But, what are the possible long-term outcomes of a food and wine festival? How does a food and wine festival collaborate with its key constituents to achieve desired long-term outcomes?

Table 6.2 presents some of the potential long-term benefits resulting from a food and wine festival, and these are linked to the short-term benefits that a food and wine festival can produce. The outcomes of food and wine festivals have been categorized into those that are economic, social and environmental. Although the contents of Table 6.2 are not exhaustive, it highlights the links between the short and long-term outcomes of a food and wine festival. Furthermore, analysis of Table 6.2 illustrates the importance of capitalizing on short-term outcomes in order to develop longer-term outcomes through the implementation of strategy.

Table 6.2 Food and wine festivals: some short- and long-term outcomes, strategies for development, and stakeholder ‘benefactors’

Producing long-term economic, social and environmental outcomes (e.g. those outlined in Table 6.2) resulting from a food and wine festival is best done in collaboration with all the festival stakeholders. Given that the primary aim of a food and wine festival is to enhance the sustainability of the hospitality, food and wine industries, their expectations and desired outcomes should, however, be given the most serious consideration. Breaking the outcomes down into those that are economic, social and environmental is useful, but noticeably these are invariably interrelated, and there are generally synergies between them. Once the long-term outcomes of the festival are decided upon, specific objectives and targets can be then set.

There is the expectation that most tourism events (e.g. food and wine festivals) will produce a positive economic impact for their host communities. The economic impact of a food and wine festival, like other types of events, is measured in terms of: the value-added contribution it makes to the host community’s gross product; the employment it generates; and the level of tourist visitation to the host destination that it induces. While bringing new income into the host economy by way of tourism is integral to producing a positive economic impact for the host economy, the long-term economic outcomes of food and wine festivals, such as industry infrastructure and employment, can be enhanced by maximizing the value-added contribution they make to the host communities’ gross product. Thus, a food and wine festival can enhance its longer-term outcomes by adopting a strategy that promotes food and wine production, and value-adding practices related to the production of food and wine within the host community. Such a strategy requires not only the co-operation of the food and wine industries, but also that of other facilitating industries, including the agricultural and farming industries. In addition to this, the role of government in facilitating the implementation of such strategies is invariably integral to their success.

There has been a tendency for the events sector to justify the staging of events, which as mentioned are often funded by the ‘public purse’, by the level of economic impact that they produce. Currently, there is much discussion about the reliability of such analysis, and the techniques that have been used to determine the economic impact of event in the past (see, for example, Dwyer et al., 2003). Further to this discussion, there is an increasing acknowledgement that special events, including food and wine festivals can contribute to the development of social capital in their host communities (see, for example, Arcodia and Whitford, 2006). Food has long been understood as a symbol of personal and group identities, creating a sense of both individuality and group membership (Wilk, 1999). When food and wine festivals promote local and international foods, they facilitate social and cultural exchanges, which create new forms of social and intellectual capital within their host communities.

One of the most innovative developments in the events sector in recent years is the notion that events can be more environmentally friendly than they have been in the past. This has translated to the development of a range of initiatives, policies and tools to reduce the negative environmental impacts of special events, such as ‘waste-wise’ and recycling programmes. The fact that food and wine are the central theme of food and wine festivals provides them with a unique opportunity to produce positive environmental outcomes for their host communities. If food and wine festivals are able to increase the production of local food and wine, and its consumption, within the local community, both food and wine travelled miles are reduced. By reducing the number of miles that fresh produce travels from the ‘farm to the plate’, various factors which are detrimental to the environment are minimized. For example, fuel consumption is reduced, not only with regard to delivery of the produce to the consumer, but also with regard to the delivery of waste produce to landfill sites. Overall, if this strategy is successful, the ecological footprint of host communities can be reduced, which has the potential to produce substantial benefits for the local, and ultimately, global environment.

In addition to these initiatives, promoters and managers of food and wine festivals have enormous potential to produce a range of positive environmental, and economic and social, outcomes for their host communities by affiliating their festivals with the organizations that are committed to ethical consumption and biodiversity, such as the Slow Food movement or a Fair Trade organization (see Exhibit 20.1).

The synergies that exist and can be developed between the Slow Food movement and other similar organizations, and food and wine festivals are apparent, but require an understanding of their potential for them to be realized.

The Melbourne Food and Wine Festival: Enhancing the Long-Term Benefits Through the Hospitality, Food and Wine Industries

In 2007, the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival employed a number of strategies to enhance the long-term economic, social and environmental outcomes of the festival. These were achieved in conjunction with the hospitality, food and wine industries through a range of events – each developed with specific outcomes.

Local food and wines were promoted through a number of initiatives. The menu for the ‘Longest Lunch’, for example, was developed around Victorian food produce and wines from the festival’s wine partner Brown Brothers and by Melbourne’s 2006 Caterer of the Year Delaware North Corporation. In Melbourne the event was host to over 1,400 guests. Regional Victoria hosted 20 ‘Longest Lunches’; for each of these the menus were developed around local food and wine, and produced by local chefs and winemakers. While the short-term outcomes of these events include an increased demand for local produce and services, and exposure of Victorian food and wine, it is envisaged that the long-term benefits will be a sustained demand for regional produce and services, e.g. tourism. A ‘Longest Lunch’ was also staged in Singapore as part of Australia’s RSVP Program (Melbourne Food and Wine Festival, 2007a).

Both ticketed and non-ticketed events were incorporated into the festival program designed to educate festival participants about food and wine culture. The MasterClasses, a series of ticketed events, provided attendees with an opportunity to learn about food and wine culture from some of the world’s master chefs and winemakers. The MasterClasses were held at the Langham Hotel (the festival’s hotel partner). Out of the Frying Pan, another ticketed event was designed to respond to the ways in which the media is impacting the hospitality, food and wine industries. The all-day event was billed as a ‘thought-provoking all-day conference for anyone interested in food, eating out and the food media; the future of food; and how the face of Australian food will be shaped in the coming years’ (Melbourne Food and Wine Festival, 2007a).

The programming of non-ticketed events on the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival’s programme increased the accessibility of the festival for the Melbourne and Victorian community. This is an important aspect of publicly funded event and festivals. Non-ticketed events were incorporated into the festival’s programme at Federation Square in Melbourne, including cooking demonstrations and two newly created public events: The International Flour Festival and Wicked Sunday. The hospitality, food and wine industries were integral to the success of these events, as they provided their expertise as exhibitors, suppliers, and vendors at the events, and as ambassadors. The events were well attended by the public and highlighted to festival management the interest that Victorians, and visitors to Victoria, have in food and wine culture. The public events enable the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival to engage with a wide cross-section of attendees, thus enhancing the opportunities to create greater social outcomes in the host community.

Other initiatives and collaborations were also essential in realizing both the short and long-term benefits of the festival. For example, the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival is certified as a Waste Wise Event by the Victorian Government’s Department of Sustainability and the Environment (DSE). As part of this certification, the festival has followed the five step approach recommended by the DSE to consider the environmental impact of the festival and develop strategies to neutralize them. For example, recycling and waste reduction systems are employed to avoid waste and litter where possible; the use of reusable packaging is promoted instead of disposable packaging; and sustainable waste management systems are promoted to attendees at the festival. Importantly, the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival works with its key stakeholders – the hospitality, food and wine industries – and encourages them to embrace the notion of sustainability, not only within the context of the festival, but also within their own operations.

In this chapter, the ways in which food and wine festivals collaborate with their stakeholders to produce a range of outcomes for their host communities were examined. These were categorized as being social, economic and environmental, and it was also noted that there are synergies between these outcomes. In an era of increasing competition in the event market place, the potential for food and wine festivals to contribute substantially to their host communities enhances both their own sustainability and success.

While the event sector has burgeoned in the past few decades, many events have found it difficult to survive. Food and wine festivals, however, are in the unique position of having two essential cultural symbols as their core attributes, and it is perhaps for this reason that they have become increasingly popular. Thus, the food and wine theme is a most valuable asset that can be used to enhance the economic, social and environmental outcomes of a food and wine festival – in the short term, and most definitely in the long term.

References

Anwar, S.A. (2004). Festival tourism in the United Arab Emirates: First-time versus repeat visitor perceptions. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(2), 161–170.

Arcodia, C.V. and Whitford, M. (2006). Festival attendance and the development of social capital. Journal of Convention and Event Tourism, 8, 1–18.

Charters, S. and Ali-Knight, J. (2002). Who is the wine tourist? Tourism Management, 2(3), 311–319.

Clarkson, M. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117.

Davidson, C. and Carlsen, J. (2002). Event volunteer expectations and satisfaction: A study of protocol assistants at the Sydney 2000 Olympics. Paper presented at the Annual Council of Australian Tourism and Hospitality Educators’ Conference, Edith Cowan University.

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., Spurr, R. and Ho, T.V. (2003). Computable generalised equilibrium modelling in tourism. Paper presented at Cauthe, Coffs Harbour.

Elstad, B. (1996). Volunteer perceptions of learning and satisfaction in a mega-event: The case of the XVII Olympic Winter Games in Lillehammer. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 4(3/4), 75–84.

Fairley, S., Kellett, P. and Green, B.C. (2007). Volunteering abroad: Motives for travel to volunteer at the Athens Olympic Games. Journal of Sport Management, 21(1), 41–57.

Freeman, E.R. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman, Boston, MA.

Gorney, S.M. and Busser, J.A. (1996). The effect of participation in a special event on importance and satisfaction with community life. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 3(3), 139–148.

Hede, A.-M., and Jago, L.K. (2005). Perceptions of the host destination as a result of attendance at a special event: A post-consumption analysis. International Journal of Event Management Research, 1(1), 1–11.

Melbourne Food and Wine Festival (2007a). 2007 Melbourne Food and Wine Festival Program. The Age, Melbourne.

Melbourne Food and Wine Festival (2007b). 2007 Melbourne Food and Wine Festival Web Site, http://www.melbournefoodandwine.com.au/ accessed 15.04.2007.

Mohr, K., Backman, K., Gahan, L. and Backman, S. (1993). An investigation of festival and event satisfaction by visitor type. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 1(3), 89–98.

Saleh, F. and Wood, C. (1998). Motives of volunteers in multicultural events: The case of the Saskatoon Festival. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 5(1/2), 59–70.

The Age (2007). The Age: Audience and circulation, http://ageadcentre.fairfax.com.au/adcentre/newspapers/age/audcirc.html accessed 01.03.2007.

Uysal, M., Gahan, L. and Martin, B. (1993). An examination of event motivations: A case study. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 1(1), 5–10.

Walle, A.H. (1996). Festivals and mega-events: Varying roles and responsibilities. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 3(3), 115–120.

Wilk, R.R. (1999). ‘Real Belizean food’: Building local identity in the transnational Caribbean. American Anthropologist, 101(2), 244–255.

Yuan, J.J., Cai, L.A., Morrison, A.M. and Linton, S. (2005). An analysis of wine festival attendees’ motivations: A synergy of wine, travel and special events? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(1), 41–58.