CHAPTER ONE

‘You are old, Father William,

the young man said,

and your hair has become very white,

and yet you incessantly stand on your head,

do you think, at your age, it is right?’

LEWIS CARROLL

There was a time when a sportsman of any kind was considered too old at 28, over the top at 30. ‘Ageing legs’, the commentators would say, knowingly. Sport was alright for young people and students, but certainly too frivolous for anyone over thirty, and downright irresponsible for a family man. The older you got, the less exercise was recommended.

These prophecies were, of course, self-fulfilling. We say we are too old, so we stop taking exercise, so we become less fit, so we cannot do as much. How things have changed! Nowadays the family man is being urged to take more exercise, cut down on his cholesterol intake and reduce his waistline, for the sake of his heart.

The first question people will ask is: am I too old to take up running? The answer to that is that you are never too old, though it must be said that the number of ninety-year-olds in competition is pretty small. What they are really asking is: Is it too late? Can I still hope to perform as well as I did when I was 18?

Don’t worry! The world is full of examples of what can be done; some of them you will come across in this book. The seventy-year-old weight-lifter is stronger than the average thirty-year-old, the seventy-year-old ballet dancer is more flexible than the average thirty-year-old and the fit seventy-year-old runner will outrun the majority of thirty-year-olds at any distance over a mile. The 70-year-old Steve Charlton recently ran 10 kilometres in under 38 minutes, which would put him in the top 10% of most races in Britain or North America.

Such people owe their achievements not to the fact that they were outstanding when they were younger but to the fact that they have continued to practise the activity they enjoy.

It’s easier for those who have been famous, because society tolerates them, even celebrates them; we can recall Jean Borotra and Kitty Godfrey playing tennis into their nineties, or Gene Sarazen teeing off at Augusta in the Masters. For those who are less distinguished, though, it sometimes requires moral courage, and this book is designed to reinforce that courage.

When we are young, we feel immortal and in a sense we are, because our cells renew themselves constantly. As we get older, the rate of cell division slows down, there is a loss of elasticity and some tissues perform less efficiently (see Chapter 2). The questions we need to look at are:

How early do these changes set in?

Is there anything we can do to reverse the process?

What level of performance can we expect at a certain age?

Am I too old to start?

Nigel Stuart-Thorn took up running at the age of 45. Twenty-five years later he is still running two thousand miles a year and racing almost every weekend. When aged 69 he won the over-65 category in the French half-marathon championships, in 90:13.

Athletics has the advantage of being completely measurable, so we can see just what is happening. Having been a teacher for thirty years, Bruce has seen that in our civilisation, people reach their physical peak between the ages of 16 and 18, and from then on their physical condition depends on their physical activity. Former pupils who come back a year or two after leaving school are already less fit, unless they have got into active sport. One of the spin-offs from the Vietnam war was that American surgeons had the opportu-nity of examining a lot of young corpses, and they found that most of those in the 19–21 age group already showed signs of degeneration, in the sense of increased fat storage and higher fat levels in the blood.

For those who take up regular training, it is quite different. We can look at records and see that it is possible to remain at the very highest level up to the age of 35, if not further, as long as you have the motivaton to train properly. Linford Christie and Merlene Ottey showed that this is true for the sprints. In the longer distances, we can quote the examples of Carlos Lopes winning the World cross-country title and the Olympic marathon at the age of 37 and Eamonn Coghlan For those who take up regular training, it is quite different. We can look at records and see that it is possible to remain at the very highest level up to the age of 35, if not further, as long as you have the motivaton to train properly. Linford Christie and Merlene Ottey showed that this is true for the sprints. In the longer distances, we can quote the examples of Carlos Lopes winning the World cross-country title and the Olympic marathon at the age of 37 and Eamonn Coghlan running a sub-four-minute mile at the age of 40. The message we can take from this is that it is possible to reverse most of the effects of ageing by taking the right kind of exercise.What are the signs of ageing? By the late thirties, and sometimes as early as thirty, we can see the following:

increasing weight

thickening waistline

declining strength

poor posture

lack of vigour

loss of flexibility

slower movements

breathlessness

lack of stamina

thinning hair

wrinkles

These outward signs are often accompanied by a general feeling of heavi-ness and malaise, sleeplessness and loss of appetite. Almost all of these things can be reversed by exercise:

Your weight and your waistline will be brought down by burning up more calories per week and by sensible eating.

Your muscular strength will improve rapidly with training.

As your abdominal and back muscles get stronger and your fat declines, your posture will improve.

The confidence and sense of well-being which come from being fit will make you more vigorous.

Flexibility can be improved by regular stretching exercises.

With less weight to carry and with increased fitness and strength, you will move faster and more easily.

Training brings a big improvement in oxygen intake. You will still get breathless when training hard, but you will be able to cope easily with ordinary life.

The increase in your powers of endurance will surprise you. Those who couldn’t jog a mile can become fit enough to run a 26-mile marathon.

This still leaves us with the thinning hair and the wrinkles, but somehow, when you are fit healthy and happy about your body, they don’t seem to matter as much.

To get an idea of what can be achieved by dedicated over-forty athletes, look at Table 1 below, which shows the current world records for over-forty men and the Olympic winning performances for 1928, in the standard running events. (Note: No comparisons have been made for women, because, with one exception, there were no events for women longer than 100m before WWII. It is worth noticing that Podkopayeva’s world over-40 best for the 800m, 1:59.25, is superior to the 1968 winning Olympic time.)

Table 1: Men’s track records

Distance |

1928 Gold |

2001 over-40 record |

100m |

10.8 |

10.6 |

200m |

21.8 |

21.86 |

400m |

47.8 |

48.1 |

800m |

1:51.8 |

1:51.25 |

1500m |

3:53.2 |

3:46.7 |

5000m |

14:38 |

13:45.6 |

10000m |

30:18.8 |

28:30.88 |

Marathon |

2hr32:57 |

2hr10:42 |

In 1928, the athletes were mostly university students in their twenties. These performances were the peak of physical achievement in their day. The best of today’s over-forties have equalled or surpassed these standards. The four-minute mile was considered impossible until Roger Bannister did it in 1954, but now it’s been done by a veteran. In the longer events, where modern training has really paid off, the achievements of today’s best veterans surpass the runs of ‘immortals’ like Nurmi and Zatopek, and in the marathon the over-40 record is superior to Frank Shorter’s 1972 Olympic winning time.

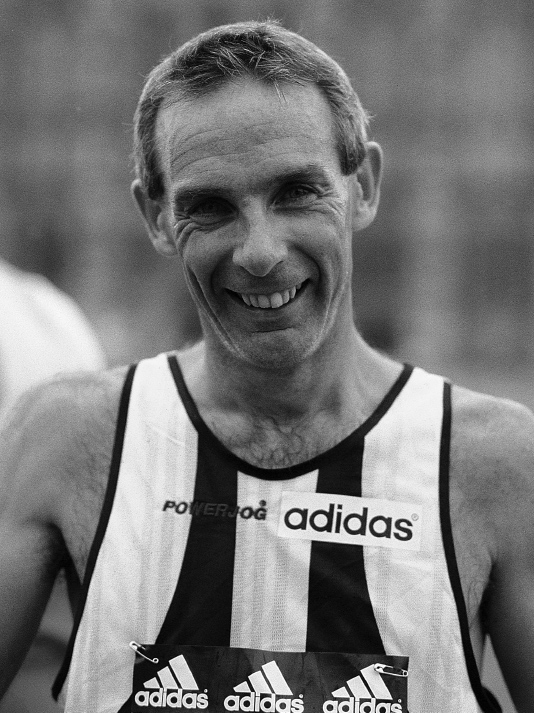

Keith Anderson

We can give you one more good example of what the older runner can achieve. Keith Anderson, when he was 31, was an overweight chef, with a demanding job, smoking 25 cigarettes a day. Ten years later, at the age of 41, he was marching into the Commonwealth Games stadium in Kuala Lumpur, as a member of the England marathon team. He went on to finish ninth in the marathon, the second of the six British runners.

These figures give you an idea of what can be achieved, at the highest level. We are not asking you to out-perform Zatopek or Shorter, just to make an improvement in your own personal level of fitness – and it can be done! The files are bulging with letters from men and women who have taken up the sport later in life. Not only have their health and fitness improved enormously, they have learned to savour life. It is hard to explain to an unfit person how much more alive you feel when you are really fit and healthy – it has to be experienced.

Bruce running in 1962 ... and 1989

However hard you train, there will come a time when your racing speed will get slower.

BRUCE: ‘I have an exact record of every race from the age of 20, when I left the Army, to the age of 32, when I retired from international competition. I started competing again as a veteran at the age of 43, doing the Sunday Times Fun Run, and from then on I have a pretty continuous set of results, mostly over distances from 4k to the half marathon.

‘In the Sunday Times Fun Run, held over the same four kilometre course at the same time of year, I slowed from 12:20 to 13:20 over a ten year period (from age 43 to 53). This represents 15 seconds per kilometre over 10 years, or 1.5 seconds/km/year. At the 5000m, my best racing distance, I was consistently around the 13:40–13:45 mark from 1960 to 1967, when I was just 32. Thirty-one years later I ran 17:40 for a 5k road course, a fall-off of 240 seconds, which represents 48 seconds per kilometre, which comes out at 1.5 seconds/km/year. Over 10000m, I ran 28:40 in 1967 and 32:30 at the age of fifty, some eighteen years later. This fall-off of 230 seconds, or 23 seconds per kilometre over 18 years, comes out at 1.3 seconds/km/year.

SUE: ‘My pattern was completely different. I started road running when I was 46, but I wasn’t training very hard, so when I got into a harder training regime, my times improved a lot, in spite of getting older. The performances went up and down more in line with how hard I was training, rather than with increasing age. At 42, I ran about 20 minutes for the Sunday Times 4k, untrained, 17:00 at the age of 48, after a year of good training, and 16:20 two years later, when I was 50. Similarly, when training hard for the Centenary Boston Marathon in 1996, at the age of 54, I ran my fastest 10k for five years and ran 90:30 for the half marathon, equalling my best time of five years earlier.’

Of course these are just personal results, and as we know, in any one year you may get a particularly good run, whereas another year you may have a bit of an injury, or you may run your best race when the wind is blowing hard.

‘The pleasures and rewards of running are immeasurably greater for me at 46 than they were at 16 or 26. That is one of the most important and surprising discoveries of my middle life.’

ROGER ROBINSON

Heroes and Sparrows, 1986

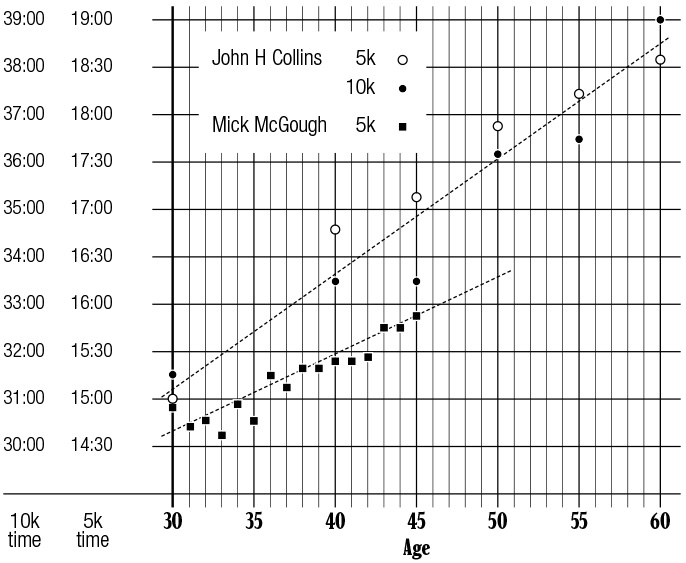

Fig. 1 shows the patterns of decline in two men who were good runners in their twenties and thirties and have gone on into over-forty competition. For Mick McGeoch we have year-on-year best times for 5000m, and for John Collins we have best performances in five-year age-bands, at 5k and 10k. There are fluctuations, which can be put down to fitness, injury or weather conditions, but overall, they both show a decline of about 1.5 secs/km/yr.

Fig.1

We started out with some pretty definite ideas on this topic. However, before starting on this book, we thought it would be a good idea to ask other over-forties for their experiences and their race results over the years – something which had not been done before. We put out an appeal through the newsletters and websites of the various veteran associations.and had almost two hundred replies within a few weeks.

The results were very illuminating – and totally confusing. There seem to be as many different patterns as there are individuals. Some have started at the age of nine, some at sixty-nine. Some have had a successful running career and then declined, while others have come from nowhere to become top-class veterans. Some have started out as sprinters and finished up as marathoners, others have gone the other way.

What was really striking was the way in which people who had been running on and off for years could show improvement and set personal bests in their fifties and even in their sixties. Take my friend Ted Townsend for example. Ted started running when he was 35, and before the age of 40 posted a respectable series of times – 41 minutes for the 10k and 1 hr 45 for the half marathon – on the basis of training hard two or three times a week. As he got older, he trained less hard but more often, and his times actually got better. At 45 he set a PB of 38:57 for the 10k and got his half marathon down to 1 hr 29 and as an over-50 he not only equalled his 1 hr 29 PB for a half marathon, he set a personal best for the marathon of 3 hr 24, forty minutes faster than he had been able to run in his thirties.

When someone takes up running for the first time, or comes back to it after a very long break, he or she will improve very quickly to start with – maybe five to ten seconds per mile (three to six secs per km.) per year, which means knocking a minute off the 10k time. After the second year this graph of improvement will start to level off, and eventually the graph of improvement due to training will collide with the graph of deterioration due to age (see Fig. 3). For a while you may be able to stay on a plateau, by training harder or by moving up to different events, but a time will come when you have to accept that your times are going to get slower rather than faster. This is where you have to change your outlook.

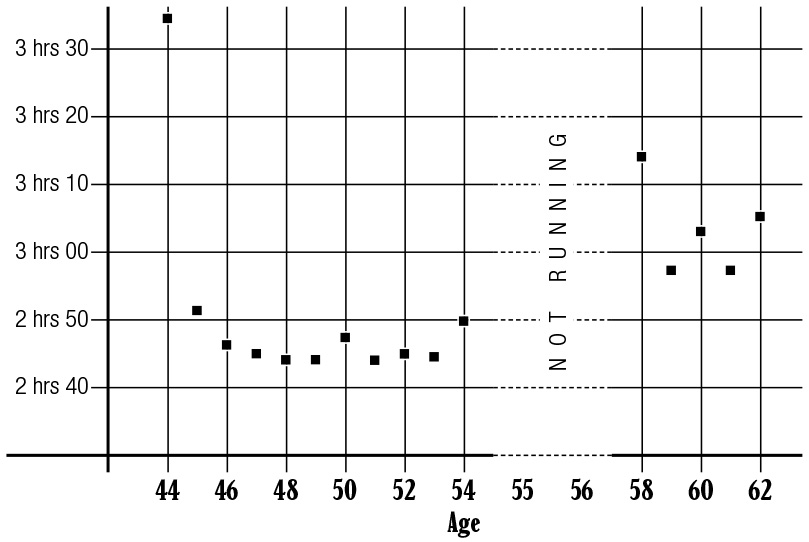

In Figs. 2 and 3 we see the typical pattern of runners who come to the sport later in life. With Gareth Jones (Fig. 2) we have yearly best performances at 10k, and with Richard Cashmore (Fig. 3) we have best times for the marathon. Since Richard was racing five or six marathons every year in his early years, we get a more even curve here than in the later period where he only raced once or twice a year.

Fig.2: Gareth Jones - 10k times

The main points here are:

Whatever your age, it takes about five years from getting started to reaching lifetime bests.

By far the biggest improvement is made in the first couple of years.

If you get the training right, performances for the late starter can go on improving into your late forties and even early fifties.

It must be said that both these runners are highly talented. We have chosen them because they have accurate long-term records, but the principles would apply equally to a fifty-minute 10k runner or a four-and-a-half-hour marathon runner.

We can get an even better idea of how people slow down by taking the average from a large number of people.

The British Veterans Federation compiles Merit Tables, based on many performances over the whole age range. In the 5000m we find that the Grade One standard falls by 2:42 between the ages of 40 and 60. This drop of 32 seconds per kilo-metre over 20 years gives us 1.6 secs/km/year. Between the ages of 60 and 70 the decline in performance is more rapid – 2.4 secs/km/year. It is hard to extrapolate much further than that, because there are not many over-seventies clocking up serious performances, but the patterns are very consistent. The difference between the men’s world best for 5000m, from 40 to 65, is almost three minutes – which is 36 secs/km over 25 years, or 1.4 secs/km/year, but there is a very big fall-off, two minutes, between the over-65 and the over-70 world record, which represents a decline of 4.8 secs/km/yr.

Fig.3: Richard Cashmore - Marathon times

Using both the tables for the men’s 10km we find that after the age of 60 the decline is more like 4 secs/km/year. However, with increasing numbers of serious athletes running in their sixties and seventies we would expect to find that this decline is not so rapid – and since we started this book, Ed Whitlock (see here) has improved the over-70 10k record to an amazing 38:04. This is 3 mins 50 secs slower than the over-60 record, which is a decline of only 2.3 secs/km/yr.

The figures for women follow much the same pattern, but since they run more slowly, the decline in seconds/km/year is slightly greater. In the 5000m, we find that the decline is a little over 2 seconds per km/year, and at 10000m about 2.5 secs/km/year over the 40–60 range. After that, we really cannot be accurate, because the number of runners is not great enough.

Not surprisingly, we find that those who train the hardest suffer the least decline in performance. Pat Gallagher (see here), who has been training hard since her late thirties, is an excellent example of this. As a W35 she ran 17:08 for 5000m, and as a W50 she ran 18:22 – a decline of only 74 seconds, which works out at frac-tionally under 1 second per kilometre per year, and her times at 1500m and 10k show a similar pattern.

There is still plenty of room for improvement in the over-90 and over 100 age group records. In the World Veterans Championships in Brisbane, the 101-year-old Australian Les Ames covered the 100m in 70 seconds and the 1500m in just under 20 minutes. It is only when we get a number of top class runners, male and female, carrying on into their seventies and eighties and competing against one another, that we will find out what the human body really can do. Until then, we must still say, as Dr. Johnson said about the dog walking on his hind legs: ‘the wonder is not that they do it well, but that they do it at all!’

‘I thought I would tell you, my life was going nowhere, but since jogging came along I have had 25 years of joy. It’s been heaven. I love running and I love watching it. I’ve run in places I never thought I would see.’

FRANK COPPING, 77

Before starting on a running programme, you must have a clear idea of what your goals are. As we have learned from the letters we have received, there are many different reasons for running, and so the same training will not suit every-body. Some would say that a veteran runner is one who is no longer improving, but that is by no means the case. Someone who takes up the sport at 46 may go on getting better up to the age of 49 and then, approaching the age of fifty, may realise that he is ready to step into the leading ranks of over-fifty runners. From being either a has-been or a never-was, he has the prospect of winning prizes, running in international competitions, maybe representing his country.

Even without taking age into account, there are at least three main cate-gories of runner:

elite competitors: these people are at the top of the age-group rank-ings and they are prepared to train as hard as possible to achieve their goals.

club runners: these people are also competitors, but they are not aiming for the very top. They will have particular events to train for at different times of the year – maybe a spring or autumn marathon, some track races in the summer, some inter-club relay events. Their main concern is staying fit and being able to perform respectably.

non-competitive runners: these people run either because they enjoy running or because it is their chosen way of keeping fit and healthy.

The mental approach dictates the schedules you embark on and your attitude to them.

For example, suppose that we have a period of really bad weather in January. The elite runner will carry on with his training. If he can’t do his repeti-tion kilometres on the road he will go to the nearest track and do them there. If the track is closed he will drive to a gym and do them on a treadmill. The club runner will not be prepared to give up the extra time, so he will just put on an extra layer of clothing and go out for a short run in the snow. The ‘keep-fit’ runner will be on a programme which includes activities other than running, like swimming or weight training, so he can concentrate on the indoor activities and save the running until the weather improves.

If you have just taken up running, you may start off as the ‘non-competitive’ type, then get drawn into a club, and maybe even become an elite runner. If you have been running seriously for twenty years before reaching veteran status, you may well move the other way, competing seriously in the first few years, then being satisfied with club-level competition and later on concentrating mainly on keeping fit and just having the occasional race for fun.

The ‘new wave’ runner has an entirely different attitude to the long-time runner. The newcomer to the sport is discovering for the first time all the sensations of feeling fit, running fast, passing people in races. He has all the enthusiasm of the eighteen-year-old inside a forty-year-old body. This can sometimes be dangerous, but it can also lead to great achievements.

For this reason our rule of thumb is that the athlete should train according to ability and ambition rather than age or sex. If somebody has improved, say, from a 5 minute 1500m to 4:50, and wants to get better, the same principles apply whether we are dealing with a 15-year-old boy, a 40-year-old woman or a 50-year-old man.

Having said that, there are differences in training, depending on the athlete’s background. The long-time runner already has thousands of miles of training behind him. It will take him less time to move up to harder training than the newcomer who has never trained at that level.

There are plenty of good reasons to run, but there are also powerful forces pushing in the other direction. What is life if we cannot enjoy it? Are not good food and good drink inseparable from good company? With air pollution, radia-tion, food additives and global warming, our chances of survival are slim, so why not just eat, drink and be merry?

BRUCE: ‘Why not? I eat well, drink moderately, sing quite a lot and am frequently merry. The point is that being a runner I can work off the food and the alcohol without putting on weight. I can enjoy life more and do more because I am healthy. Running should add to your life, not diminish it.’

Other insidious remarks are along the lines of: ‘You should act your age!’ and ‘Exercise can do more harm that good.’ Like all propaganda, this is incomplete truth. The fact that over twenty years one or two people have died while running the London Marathon does not mean that running kills you. Yachtsmen are more likely to drown than non-sailors and climbers are more likely to have climbing accidents than non-climbers. Overweight joggers occasionally die while jogging.

What is overlooked is the large number of non-exercisers who die whilst non-exercising. Bed is a dangerous place to be – a lot of people die in bed.

We are not immortal. We are all affected by the ageing process and it would be stupid to ignore this, but that does not mean we cannot slow it down. Tennyson’s words, from his poem Ulysses, sum it up:

‘Though much is taken,

much abides, and though

We are not now that strength

which in old days

Moved earth and heaven,

that which we are, we are:

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate,

but strong in will

To strive, to seek,

to find and not to yield.’

Fine words, but where do they get us? They might get us to take the long view, for a start, and they might stimulate that sense of purpose and challenge without which nothing is achieved. Working or training, without a sense of purpose, is drudgery. If you have nothing left to live for, you might as well die. If you are forty when reading this, you probably have more than half your life ahead of you. If you are going to live a long time you had better take care of yourself.

Fitness is not the same as health. Being fit will not protect you against every known disease, but it will shift the balance onto the credit side. It is now proven that those who exercise regularly are much less likely to suffer from the cardio-vascular diseases such as strokes and heart attacks. The extra strength and flexibility which comes from fitness will protect you against the little accidents which tend to ambush us in middle age – the strained back, the twisted ankle.

Ten reasons for running

Running keeps your weight down

Running makes you fitter

Running lowers your cholesterol level

Running lowers your blood pressure

Running gives you confidence

Running helps you live longer

Running improves your bone density

Running gives you great legs

Running makes you feel better

Running makes you look better

What fitness gives us is a safety margin, a reserve of vitality which enables us to cope with emergencies. You come back on the last train from London. You are four miles from home, the car won’t start and it’s starting to snow. In a situation like this, someone who is not physically robust might feel a bit panic-stricken. The breaking of one link in the chain of normal events releases a flood of irrational fears.

This is where the Ulysses factor comes in. The man or woman who has physical confidence reacts to a stressful situation in a positive way. You have been through stressful situations before, maybe in a race, on a mountainside, in a forest. You know you can cope, so you simply look around for the best solution – which in this case is an easy jog or a brisk walk home – not stressful, just a good bit of exercise – end of story.

Being able to cope with stress, having a reserve of energy, these are justifi-cations for being a runner, but they are not the real reasons. The reasons should be that we enjoy the exercise, we enjoy being fit and we enjoy a challenge. Ulysses stayed strong enough to bend the bow.

Man is a competitive animal. We are descended from those who were the quickest off the mark, the handiest with the flint axe – and the best at running away in defeat. Running in races gives us a perfect outlet for our competitive spirit. We can fight as hard as we want, beat our opponents, give them a thrashing, and yet nobody need get hurt.

In the early years of veteran competition you will find that the spirit of rivalry burns every bit as strongly as it does amongst the twenty-somethings. People who never won anything in the past can realise their dreams of winning medals and putting on an England vest. However, the longer you stay in the veteran ranks, the more you will find that your opponents become old friends. The outcome is often decided by who is injured or who has just got over an injury.

So when you turn up for a local road race and you find yourself alongside the man who beat you for the county junior title when you were nineteen, you don’t think: ‘Here’s that old git come to spoil my chances again’. You should be thinking: ‘that’s good, here is someone I can run with, who can help me achieve my goal.’ Your real enemy is time and you are both fugitives from the winged chariot. What is more likely, of course, is that you will look on him as a rival and push yourself a bit harder than usual. No one has put it better than the late George Sheehan, who said: ‘Of course we are not really competing against each other – we are all witnesses to each others achievements – but dammit, I hate to get beaten by a witness in my own age group!’

What should happen is that, like Buddhists, the older we get, the closer our attitudes move towards perfection. The ninety-year-old runner is concerned with running smoothly and consistently; he is not going to be worried about competition (because he’s outlived them all!) and that should always be our attitude.

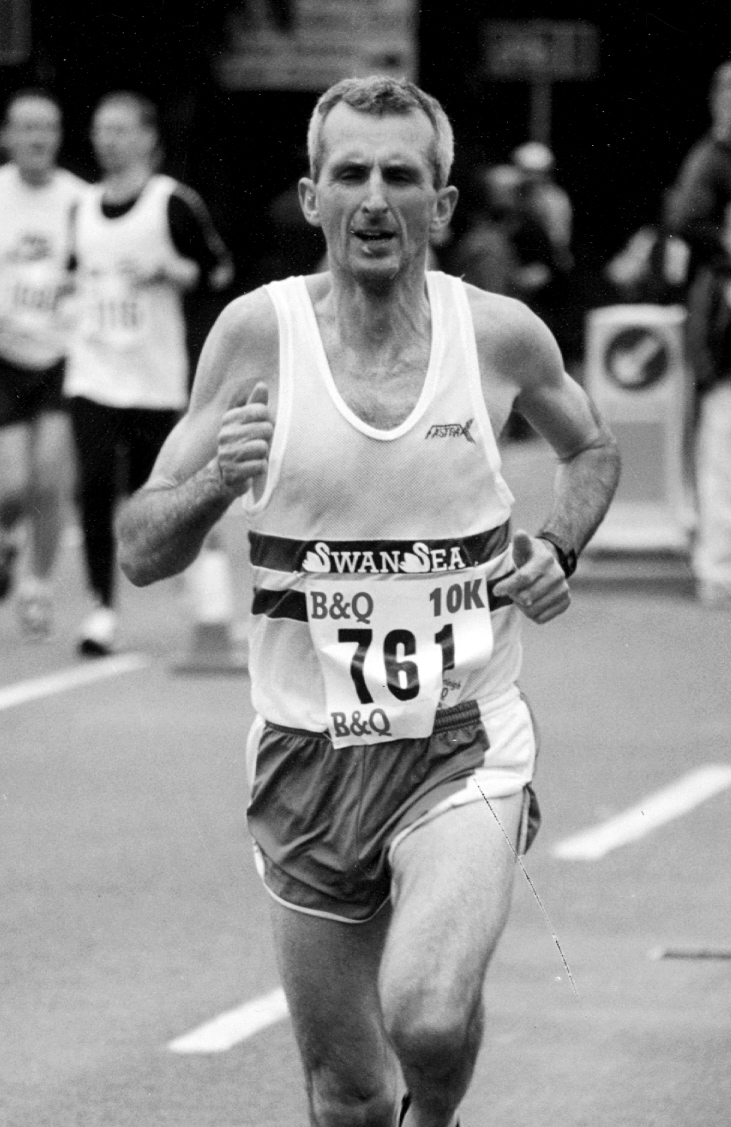

MARTIN REES

Age: 55

Occupation: steel worker

To be a successful sportsman in South Wales you have to be really good. It may be the cradle of Welsh rugby, but it also produces such runners as Steve Jones, who set a British marathon record of 2hr07:13 seconds back in 1985, Christian Stephenson and Steve Brace. Martin Rees runs for Swansea Harriers. He is a steel worker at the Port Talbot plant – a demanding job. For years he worked eight-hour shifts, rotating every few days from the Early to the Late to the Night shift, so that the sleep pattern was constantly changing. He regularly cycled to work – half an hour each way – which kept him lean and fit, but he didn’t get into running until 1991, when he was 38.

A friend persuaded him to take part in a local 10k road race, and he ran it in 44 minutes – promising but unremarkable. He then tried a ten mile race and coped with that with little trouble. Finding that he had a natural talent for the sport he joined Swansea and started training. His times improved steadily and each year he trained a bit harder. When he turned forty he was winning most of the veteran prizes in local races and soon moved into National class as a veteran. He won national titles on the road in His best times were mostly done at the age of 44 – 14:20 secs for 5k, 49:23 for ten miles and 65:37 for the half marathon – but at the age of 47 he clocked 30:25 for 10k, only just outside the PB of 30:12 he ran four years earlier, and now, at 55, he has slowed down very little. He hold the British over-50 records at 5 miles, 10 miles (50 mins, at the age of 50!) and half marathon – the latter in a remarkable 66:42.

The training which has enabled him to reach this level is fairly conventional, but tough: ‘In the autumn I put in three months of 100 miles a week and the rest of the year I run about 70-75 miles a week, running as I feel, really. I also cycle to work and back, thirty minutes each way. I like to put in a tempo run once a week and also a speed session, but if I am tired I just go easy. I very rarely do track work, but I get a lot of strength from running on hills.’