Now that you're well on your way to perfecting and popularizing your site, it's time to start looking at the second level of Internet promotion—search engines. Getting your Web site into the most important search engine catalogs is a key step in publicizing it. Working your way up the rankings so Web searchers are likely to find you takes more work, and monopolizes the late-night hours of many a Webmaster.

Directories are searchable site listings with a difference: humans, not programs, create them. That means a small army of workers painstakingly puts together a collection of sites, neatly sorted into categories. The advantage of directories is that they're well-organized. A couple of clicks can get you a complete list of California regional newspapers, for example. The unquestioned disadvantage is that directories are dramatically smaller than full-text search catalogs. That means directories aren't very useful for those in search of a piece of elusive information that doesn't easily fall into a category, like a list of the English language's most commonly misspelled words. Over the years, as the Web's ballooned in size, directories have become increasingly specialized, and full-text search tools like Google and Yahoo have become the most common way that people hunt for information.

So, given that directories are just the unattractive cousins of full-text search engines, why do you need to worry about them? Two reasons. First, some Web visitors still use directories, even if they don't use them as often as they do full-text search engines. Second, some search engines (including Google) pay attention to directory listings, and tend to rank sites higher if they turn up in certain directories. Getting into the right directories can help you start to move up the results list in a full-text search. And just like college, getting into a directory requires that you submit an application, which you'll learn about next.

The most important directory to submit your site to is the Open Directory Project (ODP) at http://dmoz.org/. The ODP is a huge, long-standing Web site directory staffed entirely by thousands of volunteer editors who review submissions in countless categories. The ODP isn't the most popular Web directory (that honor currently goes to the Yahoo directory), but other search engines use it behind the scenes. In fact, Google bases its own directory service (http://directory.google.com/) on the ODP.

Before submitting to the ODP, take the time to make sure you do it right. An incorrect submission could result in your Web site not getting listed at all. You can find a complete description of the rules at http://dmoz.org/add.html/, but here are the key requirements:

Don't submit your site more than once.

Don't submit your site to more than one category.

Don't submit more than one page or section of your site (unless you have a really good reason, like the separate sections are notably different).

Don't submit sites that contain "illegal" content. By the OPD's definition, this is more accurately described as unsavory content, like pornography, libelous content, or material that advocates illegal activity—you know who you are.

Clean up any broken links, outdated information, or any other red flags that might suggest to an editor that your site isn't here for the long term.

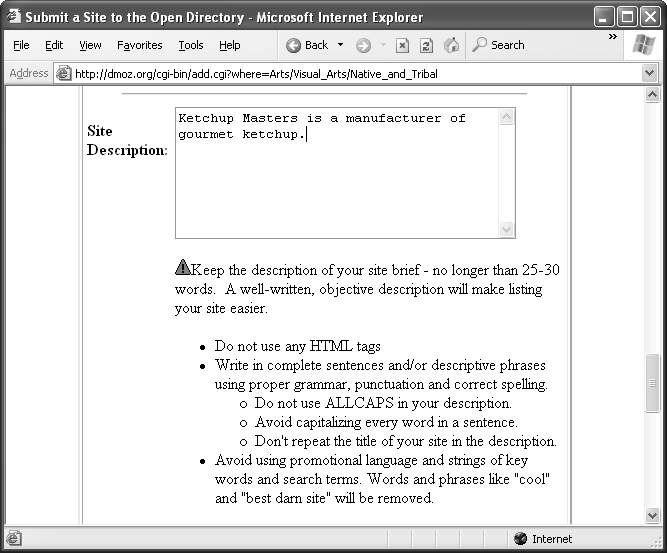

When you submit your site, describe it carefully and accurately. Don't promote it. In other words "Ketchup Masters is a manufacturer of gourmet ketchup" is acceptable. "Ketchup Masters is the best food-oriented site on the Web—the Louisville Times says you can't miss it!" isn't.

Don't submit an incomplete site. Your "under construction" page won't get listed.

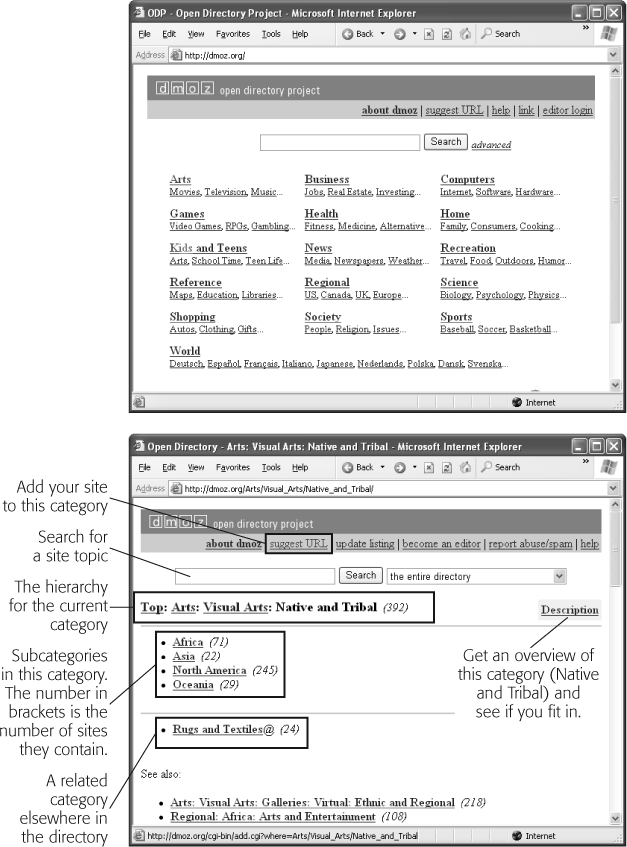

The next step is to spend some time at the http://dmoz.org/ site, until you find the single best category for your site (see Figure 11-4).

Figure 11-4. Top: When you first get to the ODP site, you see a group of general, top-level categories. Bottom: As you click your way deeper into the topic hierarchies, you'll eventually find a specific subcategory that would make a good home for your site. Here's the Arts → Visual Arts → Native and Tribal category. There are several subcategories (like Asia, with 22 sites). Categories with an @ after their names link to a related categories in a different place in the topic hierarchy.

Once you do so, click the "suggest URL" link at the top of the page and fill out the submission form (see Figure 11-5). The form asks for your URL, the title of your site, a brief description, and your email address.

Note

If you have some free time on your hands, you can offer to help edit a site category—just click the "become an editor" link. And even if you don't have editorial aspirations, why not check out the editor guidelines at http://dmoz.org/guidelines/ to get a better idea of what's going on in the mind of ODP editors, and how they evaluate your site submission?

Figure 11-5. Here's a portion of the ODP submission form for a new site. Read all the instructions carefully, fill in the boxes, and then click the inviting Submit button at the bottom of the page (not shown here).

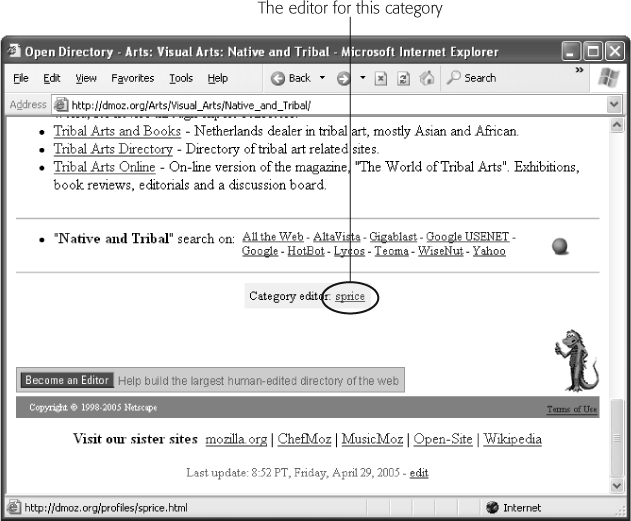

Once you submit your site, there's nothing to do but wait (and submit your site to the other directories and search engines discussed in this chapter). If two or three weeks pass without your site appearing in the listing and you haven't received an email describing any problems with it, try submitting your site again. If that still doesn't work, it's time to contact the category editor. Write a polite email asking why your site wasn't added to the listings, and include the date of your submission(s) and the name, URL, and description of your site. You can find the email address for the category editor at the very bottom of the category page (see Figure 11-6).

ODP is a great starting point, but it isn't the only directory on the block. The other heavyweight is the Yahoo directory (http://dir.yahoo.com/). Unfortunately, getting your site into the Yahoo directory takes considerably more work.

First, there's the issue of cost. If you've created a non-commercial site, you can probably get in free, but it may take persistence, emails, multiple submissions, and a bit of luck. If you've created a commercial site (one whose primary purpose is to make money) and you want to register it in the U.S. Yahoo directory, you need to pay an annual fee of several hundred dollars. And in the ultimate case of adding insult to injury, you won't get your money back if Yahoo rejects your site.

Figure 11-6. Click the editor's name ("sprice") to find out who he is, what categories he manages, and how you can email him.

To get started, you can review Yahoo's official submission guidelines at http://help.yahoo.com/l/us/yahoo/directory/suggest/listings-03.html/. However, you'll be much happier with the unofficial write-up at www.apromotionguide.com/yahoo.html, which discusses your free and for-fee options, and explains what the cryptic rejection emails Yahoo sends out really mean. And if you have a commercial Web site, or you just don't want to suffer through the slow and unreliable free registration process, you'll need to use the Yahoo Directory Submit service (formerly called Yahoo Express), which is described at https://ecom.yahoo.com/dir/submit/intro/.

Once you're done with directories (or just ready to move on), it's time to take a look at full-text search engines.

For most people, search engines are the one and only tool for finding information on the Web. If you want the average person to find your site, you need to make sure it's in the most popular search engine catalogs, and turns up as one of the results in relevant searches. This task is harder than it seems, because the Web is full of millions of sites jockeying for position. To get noticed, you need to spend time developing your site and enhancing its visibility. You also need to understand how search engines rank pages (see the box below for an example).

The undisputed king of Web search engines is Google (www.google.com). Not only is it far and away the Web's most popular search engine, it also powers other search engines (usually without being credited). Google performs an amazing amount of work—every day it chews through hundreds of millions of search requests.

Tip

For more information about search engines, including who's on top and who owns who, check out www.searchengineland.com.

It's not too difficult to get Google to notice your site. By the time your site's about a month old, Google will probably have stumbled across it at least once, usually by following a link from another site or from the ODP. As described in the box above, Google takes outside links into consideration when sizing up a site, so the more sites that link to you, the more likely you are to turn up in someone's search results.

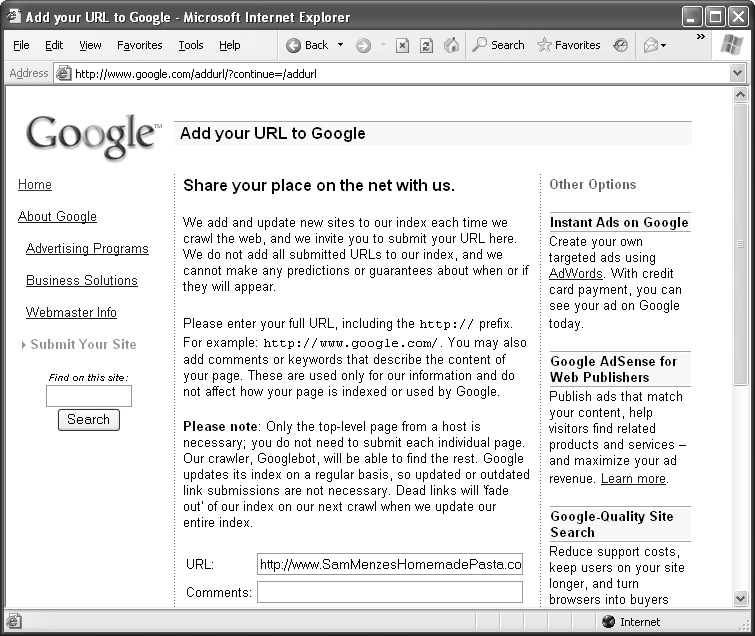

If you're impatient or you think Google's passing you by, you can introduce yourself directly using the submission form at www.google.com/addurl (see Figure 11-7). Most popular search engines include a submission form like this. Just make sure you keep track of where you've submitted, so you don't inadvertently submit your site to the same search engine more than once.

Figure 11-7. You can safely skip the comments section on this page but make sure to include the http:// prefix at the start of your Web page's URL.

You'll soon discover that it's not difficult to get into Google's index. But you might find it exceedingly hard to get noticed. For example, suppose you've submitted the site www.SamMenzesHomemadePasta.com. To see if you're in Google, try an extremely specific search that targets just your site, like "Sam Menzes Homemade Pasta." This should definitely lead to your doorstep. Now, try searching for just "Homemade Pasta." Odds are, you won't turn up in the top 10, or even the top 100.

So how do you create a site that the casual searcher's likely to find? There's no easy answer. Just remember that the secret to getting a good search ranking is having a good PageRank, and getting a good PageRank is all about connections. To stand out, your Web site needs to share links with other leading sites in your category.

If you want to delve into the nitty-gritty of search engine optimization (known to Webmasters as SEO), consider becoming a regular reader of www.webmasterworld.com and www.searchengineland.com. You'll find articles and forums where Webmasters discuss the good, bad, and downright seedy tricks you can try to get noticed.

Tip

It's possible to get too obsessed with search engine rankings. Here's a good rule of thumb—don't spend more time trying to improve your search engine ranking than you do improving your Web site. In the long term, the only way to gain real popularity is to become one of the best sites on the block.

If you're feeling a bit in the dark about how your Web site rates with Google, you'll be happy to know that Google has a service that can help you out. It's called the Google Webmaster Tools, and you can sign up your site for free at www.google.com/webmasters/tools.

Note

Before you can actually use the Google Webmaster Tools, you need to prove you own the site. To do this, Google asks you to upload a small file (a task that only a site owner can perform). Once Google finishes verifying your site, you can remove this file.

The Google Webmaster Tools let you look at your Web site through the eyes of Google. It divides its features into several sections. When you sign up, here's what you see:

Overview. This section tells you whether Google has visited your site, and whether it's successfully added your site to its index. You'll also find links to help documents that explain how Google sizes up a Web site and how you can climb the rankings.

Diagnostics. This section warns you about any problems Google has encountered, like incorrect metadata (Adding Meta Elements) or pages that it couldn't access (and therefore couldn't index).

Statistics. This section provides information about the searches that lead Googlers from the search engine to your Web site. For example, you might find out that people reach your pet food site after searching for "san francisco doggie treats." You can get even more detailed statistics using the Google Analytics tracking service described on Tracking Visitors.

Links. This section is most notable for its external link viewer, which shows you what Web sites link to yours. It's like a super-powered version of the link: search operator that you learned about on Web Rings.

Sitemaps. This section helps you build a sitemap—a special file that describes the structure of your site and the files in it. You can submit your sitemap to Google and other search engines so they know what to index. This is particularly useful if you have pages that Google might ordinarily miss, like standalone pages (those not linked to other pages).

Tools. This section lets you tweak a few miscellaneous Google settings (for example, how often it examines your site for new content). It also lets you create and analyze robots.txt files, which you can use to hide a portion of your site from nosy search engines, as explained on Hiding from search engines.

Most serious Web designers eventually check out their Web sites with the Google Webmaster Tools. If nothing else, you can use it to make sure everything is running smoothly—in other words, that Google can access your site, that its automated search robots return frequently to check for new content, and that the robots review all the pages you have to offer.

As a Web-head, you've no doubt seen several lifetimes' worth of flashing messages, gaudy banners, and invasive pop-ups, all trying to sell you some hideously awful products. It probably comes as no surprise to learn that these types of ads aren't the way to promote your site—in fact, they're more likely to alienate people than entice them. However, there are respectable paid placements that can get your site in front of the right readers, at the right time, and with the right amount of tact. One of the best is AdWords (http://adwords.google.com/), Google's insanely flexible advertising system.

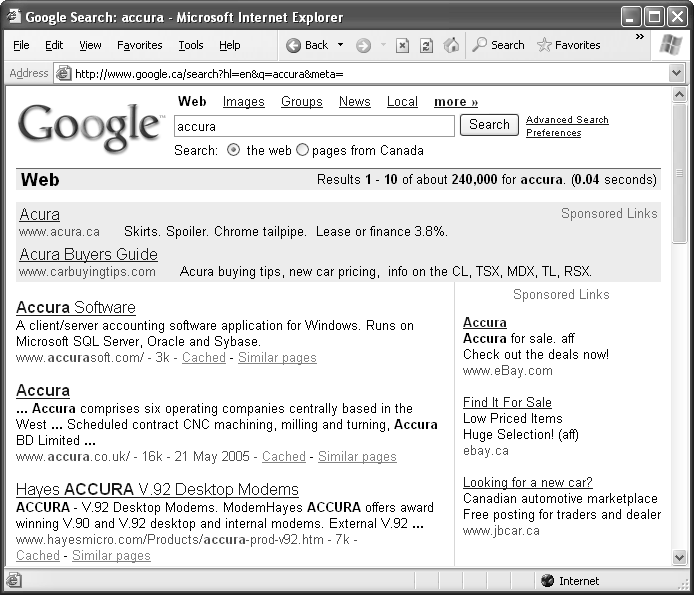

The idea behind AdWords is that you create text ads that Google shows alongside its regular search results (see Figure 11-8). The neat part is that Google doesn't show the ads indiscriminately. Instead, you choose the search keywords you want your ad associated with.

Figure 11-8. To see AdWords in action, try searching for a name brand like Microsoft. You'll see a section clearly marked Sponsored Links on the right side of the search results, or just above the search results in a yellow shaded box.

The nice (and slightly confusing) part about AdWords is that you bid for the keywords you want to use. For example, you might tell Google you're willing to pay 25 cents for the keyword "food." Google takes this into consideration with everyone else's bids, and displays the higher bidders' ads more often. But Google isn't out to rip anyone off, and it charges you only the going rate for your keyword, regardless of how much you told Google you're willing to pay. And Google doesn't charge you anything to simply display your ad on a search results page. It charges you only when someone clicks on your ad to get to your site.

By this point, you might be getting a little nervous. Given the fact that Google handles hundreds of millions of searches a day, isn't it possible for a measly one-cent bid to quickly put you and your site into bankruptcy? Fortunately, Google's got the solution for this, too. You just tell Google how much you're willing to pay per day. Once you hit your limit, Google stops showing your ad.

Interestingly, the bid amount isn't the only factor that determines how often your ad appears. Popularity is also important. If Google shows your ad over and over again and it never gets a click, Google realizes that your ad just isn't working, and lets you know that with an automatic email message. It may then start showing your ad significantly less often, or stop showing it altogether, until you improve it.

AdWords can be competitive. To have a chance against all the AdWords sharks, you need to know how much a click is worth to your site. For example, if you sell monogrammed socks, you need to know what percentage of visitors actually buy something (the conversion rate) and how much they're likely to spend. A typical cost-per-click hovers around 75 cents, but there's a wide range. At last measure, the word free topped the cost-per-click charts at $2.26, while the keyword combination llama care could be had for a song—a mere 5 cents. (And in recent history, law firms have bid "mesothelioma"—an asbestos-related cancer that could become the basis of a class-action lawsuit—up close to $100.) Before you sign up with AdWords, it's a good idea to conduct some serious research to find out the recent prices of the keywords you want to use.

Note

You can learn more about AdWords from Google: The Missing Manual, which includes a whole chapter on it, or on Google's AdWords site (http://adwords.google.com/). For a change of pace, go to www.iterature.com/adwords for a story about an artist's attempt to use AdWords to distribute poetry, and why it failed.

In rare situations, you might create a page that you don't want to turn up in a search result. The most common reason is because you've posted some information that you want to share with only a few friends, like the latest Amazon e-coupons. If Google indexes your site, thousands of visitors could come your way, sucking up your bandwidth for the rest of the month. Another reason may be that you're posting something semi-private that you don't want other people to stumble across, like a story about how you stole a dozen staplers from your boss. If you fall into the latter category, be very cautious. Keeping search engines away is the least of your problems—once a site's on the Web, it will be discovered. And once it's discovered, it won't ever go away (see the box on Tracking Visitors).

But you can do at least one thing to minimize your site's visibility or, possibly, keep it off search engines altogether. To understand how this procedure works, recall that search engines do their work in several stages. In the first stage, a robot program crawls across the Web, downloading sites. You can tell this robot to not index your site, or to ignore a portion of it, in several ways (not all search engines respect these rules, but most—including Google—do).

To keep a robot away from a single page, add the robots meta element to the page. Use the content value noindex, as shown here:

<meta name="robots" content="noindex" />

Remember, like all meta elements, you place this one in the <head> section of your XHTML document.

Alternatively, you can use nofollow to tell robots to index the current page, but not to follow any of its links:

<meta name="robots" content="nofollow" />

If you want to block larger portions of your site, you're better off creating a specialized file called robots.txt, and placing it in the top-level folder of your site. The robot will check this file before it goes any further. The content inside the robots.txt file sets the rules.

If you want to stop a robot from indexing any part of your site, add this to the robots.txt file:

User-Agent: * Disallow: /

The User-Agent part identifies the type of robot you're addressing, and an asterisk represents all robots. The Disallow part indicates what part of the Web site is off limits; a single forward slash represent the whole site.

To rope off just the Photos subfolder on your site, use this (making sure to match the capitalization of the folder name exactly):

User-Agent: * Disallow: /Photos

To stop a robot from indexing certain types of content (like images), use this:

User-Agent: * Disallow: /*.gif Disallow: /*.jpeg

As this example shows, you can put as many Disallow rules as you want in the robots.txt file, one after the other.

Remember, the robots.txt file is just a set of guidelines for search engine robots, it's not a form of access control. In other words, it's similar to posting a "No Flyers" sign on your mailbox—it works only as long as advertisers choose to heed it.

Tip

You can learn much more about robots, including how to tell when they visit your site and how to restrict the robots coming from specific search engines, at www.robotstxt.org.