THE YEAR WAS 1837, and the place was Cincinnati—the nation’s hub for all things pig. With its prime location, explosion of tanneries and slaughterhouses, and herds of swine tottering through the streets, the city had earned the nickname “Porkopolis,” shipping pork galore down river and feeding mouths near and far. And for two of the city’s accidental transplants—William Procter and James Gamble—that meant a steady supply of their business’s most precious commodity: lard.

But cooking with it was the last thing on the men’s minds. Instead, the rendered fat was the chief ingredient for their candles and soaps.

That the men had met at all—much less launched the now-largest consumer goods company in the world—was somewhat serendipitous. Procter, an English candle maker, had been voyaging to the great American West when his first wife died of cholera—cutting short his travels and leaving him stuck in Cincinnati. Gamble, an Irish soap maker, had been Illinois-bound when unexpected illness plopped him in the Queen City as well. Cupid must’ve seen a prime opportunity for meddling, because the men ended up falling in love with two Cincinnati women who just happened to be sisters. Marriage ensued, and with it came their new father-in-law’s flash of insight that the men, who were already competing for the same materials for their soap and candle-making pursuits, ought to become business partners.1

And thus was born Procter and Gamble—or P&G, as we know it today.

Though Procter & Gamble enjoyed early success, its lifeblood—the animal-fat industry—saw the first hint of its eventual undoing near the turn of the century. It was a death-march summoned largely by journalist Upton Sinclair. After a two-month investigation of Chicago’s meatpacking district, he penned a fictional tale inspired by the horrors he’d witnessed: revolting conditions for immigrant workers, unsanitary meat-handling practices, and an utter abuse of power by the nation’s “industrial masters.” It wasn’t long before the novel, titled The Jungle and first published as serial installments in the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, took the nation by storm.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t the kind of storm Sinclair was banking on. While he assumed the book would evoke sympathy for the working class (and, if all went as planned, win support for the socialist movement), readers were too shocked by his descriptions of meat production to care much about the workers’ social plight: the stench of the killing beds, the acid-devoured fingers of pickle-room men, the poisoned rats scrambling onto meat piles and inadvertently joining America’s food supply. If nothing else, Sinclair succeeded in churning an unprecedented number of stomachs. And the sinking ship of meat’s reputation brought with it another casualty: lard. As one gruesome passage described:

The other men, who worked in the tank rooms full of steam, and in some of which there were open vats near the level of the floor, their peculiar trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them to be worth exhibiting—sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard!2

The image of lard containing the renderings of people proved too vivid to purge from memory—a sort of Soylent Green prelude. Shortly after The Jungle exploded onto the scene, sales of American meat products sank by half.3 And while the book never elicited the political response Sinclair had hoped for, it did lead to a food-safety uproar so profound that the US government had to step in and calm its horrified citizens. In 1906, mere months after the book’s debut, Congress passed two landmark acts—the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906—to enforce standards for food production and help Americans feel better about what they were eating. (The two acts collectively set the groundwork for the Food and Drug Administration years later.)

Believing The Jungle failed as a social commentary but inadvertently succeeded as an exposé on food sanitation, Sinclair later remarked: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach!”4

But even if Sinclair’s book managed to sour Americans on lard, no alternatives other than butter currently existed to satisfy the country’s cooking needs. At least not yet.

Over in France, chemist Paul Sabatier had been busily developing the hydrogenation process—the act of shooting hydrogen atoms into an unsaturated chemical compound. Though his early work was limited to vapors, it wasn’t long before another scientist, Wilhelm Normann, replicated the procedure using oils—demonstrating for the first time that a liquid fat could, through deft chemical tweaking, become solid at room temperature. At the time, it seemed on par with lead-to-gold alchemy.

And best of all, the thick, creamy result of hydrogenation was exactly what P&G needed to seal their legacy. Although the company spent years oblivious to those oversea hydrogenation miracles, a pivotal moment came in 1907 when Edwin Kayser—a recent transplant to Cincinnati, and chemist for the company that owned the rights to the process of hydrogenating oil—approached Procter & Gamble’s business manager with an idea.5 Why not use this revolutionary new substance to make soap?

It didn’t take long before the dream was a reality. By 1908, the company owned eight cottonseed mills and had secured a steady supply of the oil they needed to feed production.

Elbows-deep in the cottonseed market, Procter & Gamble realized their soap making—as lucrative as it was—had only tapped the surface of cottonseed oil’s potential. And the company soon found itself facing a new conundrum: the dawn of the electrical age. Although it would be many more years before the whole country was firelessly alight, candle sales were already taking a blow, and Procter and Gamble knew they needed to keep pace with the changing world to avoid a financial nosedive. It was time to enter the kitchen.

In 1910, Procter & Gamble applied for a US patent on the use of hydrogenation for making a human-grade food product. Compared to the flowery, rhetorically brilliant hype it would later receive, the description was cool and clinical:

This invention is a food product consisting of a vegetable oil, preferably cottonseed oil, partially hydrogenated, and hardened to a homogenous white or yellowish semi-solid closely resembling lard. The special object of the invention is to provide a new food product for a shortening in cooking.6

After a few failed attempts to claim a name—“Krispo” was taken by a cracker company; “Cryst” sounded religious—Procter and Gamble settled on “Crisco,” derived from “crystallized cottonseed oil.”7 The name would quite literally become a household term.

Up until that point, a handful of processed vegetable oils had presence in America—but unlike today, their claim to fame had nothing to do with being edible. In fact, stomachs were often the last place highly refined oils would end up. Peanut oil had gained some publicity as a potential fuel: one company managed to coax a small diesel engine into running on it during the 1900 Paris Exhibition.8 And cottonseed oil made its American debut back in 1768, when a Pennsylvania doctor figured out how to collect the fat from crushed cottonseeds—which he then used as a treatment for colic.9 (Woe be to his patients, that crude oil was teeming with gossypol—a chemical that causes infertility, low blood potassium, and sometimes paralysis, and can only be removed from cottonseeds through heavy processing.10)

Ginning mills were thrilled someone wanted to haul away their cottonseed. Through much of the 1800s, the stuff had simply been left to rot in gin houses, or occasionally dumped illegally into rivers. But one man’s trash had become another man’s treasure, so to speak, and P&G had pioneered what’s now an American tradition: getting rid of agricultural waste products by feeding them to humans. The company had effectively bridged the gap between garbage and food.

By 1911, Crisco made its official debut. And what a debut it was. Almost immediately, the new fat had gained not only the nation’s trust, but also its passionate love. Within a year, over 2.5 million pounds of Crisco had flown off the shelves; by 1916, that number reached sixty million.11

How could a single product dominate the cooking world at warp speed—rising from total obscurity into an indispensible staple in a matter of months? P&G had a back-patting answer for themselves: that housewives, chefs, doctors, and dieticians “were glad to be shown a product which at once would make for more digestible foods, more economical foods, and better tasting foods.” Crisco exploded onto the scene all on its own, was the implication. It was just that good!

In reality, though, Crisco’s expedited fame was owed mainly to some of the most skillful, manipulative ad campaigns the young century had seen. Knowing it would be hard to convince housewives—the gatekeepers of America’s kitchens—to give up their familiar lard and butter in exchange for this strange new item, P&G had hyped their product like few things had ever been hyped before. The company mailed samples to fifteen thousand grocers in America. Thousands of flyers were circulated among jobbers.12 The company deftly played upon women’s burning desire to be “modern,” persuading them that clinging to animal fats in the face of this new scientific discovery would be akin to their grandmothers refusing to give up the spinning wheel.13

But most powerful of all was The Story of Crisco—equal parts advertisement and cookbook—which P&G handed out to housewives free of charge. Its 615 recipes, all united by their shared ingredient, Crisco, ranged from tantalizing (Clear Almond Taffy; Snow Pudding with Custard) to whimsical (Calf’s Head Vinaigrette; Mushrooms Cooked Under Glass Bells). The true marketing genius, however, came from the book’s introductory chapters. Carefully grooming readers into future Crisco acolytes, the book first painted animal fats in the most dismal light possible, expounding their “objectionable features” and whetting appetites for a better replacement. Crisco was presented as a panacea of sorts—healthier than lard, more economical than butter, and altogether in a category of its own. Everything other fats did wrong, Crisco did right. P&G managed to create a demand for something people hadn’t even known they wanted.

(As a peek into the different meat world of the day, the book was also busting with recipes for ox tongue, baked brains, heart, kidney omelets, sweetbreads (that’s the more appetizing term for pancreas or thymus), stewed liver, and tripe (the rubbery lining of ruminant stomachs)—all foods fit for an impressive supper back in the day. As we’ll see in the upcoming Meet Your Meat chapter, the systematic purging of these foods from the modern menu has done us a great nutritional disservice.)

In the wake of the grungy, repulsive world of meatpacking depicted in The Jungle, Crisco built its image on purity. Its factories were gleaming, sterile wonderlands. Its product was bright as snow. Its packaging included not only a tin can, but also an over-wrap of white paper, emphasizing its pristine state. Everything about the product screamed undefiled. Like the incorruptible relics of a saint, Crisco seemed eternally taintless—exactly what America, eager to wipe itself of the grime of the 1800s and enter a cleaner century, was hungry for.

Incidentally, The Story of Crisco also captured a fascinating view of fat from the early 1900s—a perspective that would face extinction once the USDA unleashed its smack down on all things lipid. In its chapter titled “Man’s Most Important Food, Fat,” The Story of Crisco remarked, “No other food supplies our bodies with the drive, the vigor, which fat gives. No other food has been given so little study in proportion to its importance.” (Emphasis in original.)

Back in the day, Crisco was indeed nothing short of a miracle. It came from plants; it was firm; it was tasty; it was cheap; it fried foods without smoking; and huzzah, it was even kosher and parava—usable with both milk and meat per Jewish dietary law. (Rabbi Margolies of New York, who was in charge of approving the food’s kosher label, remarked “the Hebrew Race had been waiting four thousand years for Crisco.”14)

It wasn’t long before this new dietary messiah had infiltrated pantries, fryers, cakes, pies, omelets, meatloaves, and the very heart of America’s psyche. During World War II, butter rationing helped push Crisco and margarine to center stage, and oils from corn and soybean joined cottonseed oil as the slippery darlings of a new food technology. It wasn’t long before science seemed to be cheering on the trend as well.

In 1961, with the famous Ancel Keys now an iron-jawed board member, the American Heart Association (AHA) officially threw its weight behind the idea that saturated fat was causing heart disease—implying that P&G’s profit-driven corralling of Americans away from lard and butter had accidentally been good for their health. Around the same year, the nation’s margarine consumption exceeded butter intake for the first time in history.15

It seemed Crisco had done the impossible and lived up to its own unbridled hype. But there was a dark side to all this purity. With cottonseed oil’s omega-6 to omega-3 ratio registering a magnitude 258 to 1, Crisco became the first ingredient to unleash unprecedented levels of linoleic acid—a polyunsaturated fat—into the American diet. Unknown to even the sharpest nutritionists of the day, Crisco had invited two killers into the American diet: trans fat resulting from partially hydrogenating oils and an astronomical intake of omega-6 fats—both now known to increase the risk of heart disease and cause inflammatory immune responses. It would be many decades before anyone realized what had gone so horribly wrong. In fact, the USDA would promote trans fats all the way up until 2005.

But long before then, there had been growing suspicion that trans fats were fatal to our well-being. As early as the 1950s, while Ancel Keys was busy winning the world over to Team Anti-Saturated Fat, other researchers were noting the uncanny connection between the use of partially hydrogenated oils (and the trans fat they contained) and the rising rates of both heart disease and cancer.16 While correlation between the two couldn’t prove causation any more than Keys’s population data could conclusively damn saturated fat, the parallel between trans fat intake and chronic disease rates were beginning to ring some warning bells.

Early research also suggested something awry about trans fats. By the 1960s, scientists realized that while vegetable oils were known to reduce cholesterol levels in controlled trials, the hydrogenated forms of those same oils failed to follow suit. In 1968, it was disconcerting enough for the American Heart Association (AHA) to take note and warn the public in a brochure titled Diet and Heart Disease:

Partial hydrogenation of polyunsaturated fats results in the formation of trans forms which are less effective than cis forms in lowering cholesterol concentration. It should be noted that many currently available shortenings and margarines are partially hydrogenated and may contain little polyunsaturated fat of the natural cis, cis form.17

(Cis is a chemistry term meaning “on this side,” in this case referring to the configuration of atoms in unsaturated fat.)

Despite fifteen thousand pamphlets going to print with a carefully worded demotion of trans fats, none of them would see the light of day. That’s because Fred Mattson—a researcher gainfully employed by P&G—convinced the AHA’s medical director to remove all traces of those incriminating statements.18 Instead of distributing the thousands of copies they’d already printed, the AHA revised the brochure to make it more palatable to the margarine and shortening industries. Decades would pass before the AHA dragged trans fats back onto the cutting block—years where countless lives were no doubt injured by ignorance of its dangers.

Remember our conversation back in chapter two on Luise Light, the former USDA nutritionist whose plans for a new food guide—one that would have cracked down on processed starches and sugars in favor of fresh, whole foods—had been so brutally mutated? As it happens, her shadowy safari through the agriculture department included a peek into the era’s trans fat research. And what she saw was shocking.

According to Light, the experts she’d convened while developing her food guide in the late seventies were already leery of trans fats—pushing for more research and expressing concern that the partially hydrogenated oils seeping into America’s food supply could be quite dangerous.19 At the same time, scientists at the University of Maryland were finishing up some intensive research on the impact of trans fats on heart disease. Their findings appeared so incriminating for the lab-created substance that it spurred the USDA to run an analysis of the margarines currently on the market, testing them for their trans fats levels—an endeavor other researchers across the globe were also gaining interest in at the time.20

The results were grim. It turned out that the margarine market was a virtual sea of trans fats, with nearly every brand, both regular and those promoted for health, containing disturbingly high levels. According to Light, the head of the USDA’s fats lab—who’d spearheaded the analysis—had attempted to spread the findings to other scientists and the public, only to have his efforts thwarted by the steely fist of the USDA. As she described the sorry scene:

The head of the fats lab told me that when he attempted to publish a paper with his findings in a peer-reviewed scientific journal … [the] USDA suppressed it, refusing to allow the information to be published. This eminent, world-renowned scientist told me, with tears in his eyes, that in his twenty-year career in research, he had never been confronted with such blatant political interference in science.21

As disturbing as that interference was, it was hardly surprising. Partially hydrogenated oils were a sacred cow for food manufacturers: they were cheaper than animal fats, had a gloriously high melting point, prolonged the shelf life of whatever they touched, and provided just the right consistency to make foods profitably addictive. That Father USDA had rushed in to protect the food industry’s favorite commodity wasn’t anything new—just business as usual.

(The head of the fats lab, Light described, was so disheartened by corporate interfering that he quit his job to head the nutrition research department at a nearby university.)

Not until 2006 did the FDA officially require food manufacturers to list the trans fat content of their products on nutrition labels. The AHA also dragged its feet until 2006, when it finally advised Americans to cut back on the harmful substance.22

But until then, the evidence against trans fat continued to mount. In 1990s, a fresh nugget of research shook up both the scientific community and the public. The study—a well-designed randomized, controlled trial—had taken a group of healthy adults and put them on a series of three different diets, identical in all ways except fat proportion: one high in monounsaturated fat; one high in saturated fat; and one high in trans fats derived from sunflower oil.23

During the participants’ trans-fat-diet phase, LDL rose while HDL dropped significantly—creating the most unfavorable lipid profile out of any of the diets, and opening a highly probable door for heart disease. While calling for more research to clarify their findings, the researchers concluded: “it would seem prudent for patients at an increased risk of atherosclerosis to avoid a high intake of trans fatty acids.”

Nonetheless, the only type of fat continuing to fall under the USDA’s sledgehammer was saturated. Despite the results of the 1990 study and other growing concerns about the impact of trans fats on human health, the 1992 food pyramid—and its accompanying pamphlet—didn’t even mention the words “trans fat,” much less warn that the substance was under investigation as a potential health hazard.

The food pyramid’s pamphlet—beneath the heading “Are some types of fat worse than others?”—stated only to limit saturated fat to less than 10 percent of total calories because it could raise cholesterol and cause heart disease. Absent were any caveats for other fat-based dietary components. And worse, the pamphlet specifically advised consumers to tilt their fat choices toward margarines with “vegetable oil” listed as their first ingredient, effectively steering folks toward some of the richest sources of trans fat in existence.24

Curiously enough, up until the 1992 Food Guide Pyramid, the USDA was probably the most lax of all the official organizations when it came to replacing animal fats with high-omega-6 oils and partially hydrogenated fats. But then again, in a theme still repeated today, public health recommendations were virtually the last to respond to advancing science—plodding along as slow, cautious, lumbering beasts chronically out of pace with the latest discoveries in nutrition.

With the trans fat hoopla brewing in the background, the showdown between saturated fat and polyunsaturated was stealing a far more public spotlight. Recall last chapter’s discussion on the Seven Countries Study. Keys had barely concluded its first follow-up when long-term trials were beginning to show that the diet-heart hypothesis borne at the population level didn’t always pan out in controlled settings.

But as often happens when a nutritional theory enters the echo chamber of mainstream belief, the results of those studies were squeezed, bent, and shoddily interpreted in order to bolster the anti-saturated-fat movement of the time. Several of the most important trials—whose innards we’re about to explore—suggested that cholesterol-lowering diets, stuffed full of “heart healthy” vegetable oils, were actually increasing total mortality, cancer rates, and even heart disease itself, despite being cited as evidence for the contrary. It was a reality swept out of sight by ideological forces and groupthink.

Let’s now take a look at what really went on behind the scenes of our most prominent diet-heart trials, and why the nation’s lust for vegetable oil—both then and now—has likely done more harm than good.

If ever a trophy study existed, the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial is certainly it. With over 750 peer-reviewed citations between its two main publications, the trial became one of the most influential and widely referenced studies of its kind, laying the foundation for widespread polyunsaturaed fat (PUFA) consumption. Even today, the study fuels meta-analyses, literature reviews, and scientific debates on the merits of saturated fat and PUFAs. Along with locking Keys posthumously in the scientific winner’s circle, it shaped a great deal of the nutritional recommendations still ringing in our ears today.

Yet the trial isn’t noteworthy because of its meticulous design. Or its tight control of variables. Or its uncontestable confirmation of the hypothesis it set out to test. It’s noteworthy because it failed on virtually every account and catapulted to fame anyway.

We’ll get back to that in a minute. But first, some background.

As you may recall, the famous Keys did a bang-up job exposing the scientific community to his diet-heart hypothesis back in the late 1950s. And once the skepticism died down, other researchers opened to the possibility that saturated fat could indeed be driving the world’s sudden rash of heart disease.

There was just one problem. No one had completed any long-term trials testing on whether swapping saturated animal fats for PUFA-rich oils would actually protect against heart disease in a measurable, verifiable, objective way. Such trials, it was reasoned, would be the dot-connecter between the existing observational and experimental evidence—but until they were conducted, too many question marks remained. Would controlled human studies unfold in the same direction as observational ones? Would a diet-induced slash in blood cholesterol actually keep heart disease at bay? Would saturated fat’s fingerprints be causally and conclusively scattered across the scene of the crime?

The time was ripe for some testing. And the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial was one of the first to rise to the challenge. While planning their research venture in 1958, the study’s investigators were perfectly clear about their intent: to test whether a cholesterol-reducing diet, low in saturated fat and high in PUFA, could slash heart disease rates.25 More specifically, the aim was to conduct a primary prevention trial—that is, prevent a disease from striking rather than treat or cure one already there. For that reason, the researchers systematically excluded folks with pre-existing heart disease, rounding up only healthy folks, about thirteen thousand middle-aged men and women from two mental hospitals close to Helsinki, to endure twelve years of dietary guinea pigging.

The setup was simple enough. For the first half of the study, one hospital—whose residents effectively acted as the control group—received the typical Finnish fare, one rich in saturated dairy fat and scant on vegetable oils.

For those same six years, a different hospital housed the study’s experimental group—serving the modified, cholesterol-busting menu theorized to combat heart disease: “soft” margarine replaced “hard” margarine and butter. A depressing mix of soybean oil and skim milk replaced whole milk. And any remaining sources of dairy fat were switched out for polyunsaturated lookalikes.

And so it went for six years: the control group in one hospital enjoyed plenty of high-fat dairy (and, consequently, saturated fat), while the experimental group in the second hospital consumed a high PUFA menu designed to hammer down blood cholesterol levels.

Then came the great switcheroo.

At the six-year mark, the first hospital replaced its dairy-fat-rich diet with the high PUFA menu, while the second hospital replaced its high PUFA menu with the dairy-fat-rich diet. This leg of the study lasted another six years. (In Science-ese, this is called a crossover design—where at a designated point in a study, the control and experimental groups swap what they’re doing. Although that’s a perfectly fine setup for some trials, it happened to be a fatal flaw for this one—and we’ll talk about why in a minute.) When it was Swap O’Clock, the researchers also initiated a “rejuvenation of cohorts,” where some younger patients were reeled in to replace the oldest ones—a maneuver to help keep age ranges equal throughout all periods of the study. Otherwise, the post-switcheroo control and experimental groups would both be six years older than during the first leg of the study.

On the surface, it looked like the researchers had pulled off exactly what they’d set out to do. Some number-crunching confirmed that the high PUFA menu successfully snipped dairy fat out of the equation—dropping it from 22 percent of total fat calories in the “standard Finnish” control diet to only 4 percent in the high PUFA diet. Likewise, the high PUFA diet averaged 68 percent of its fat calories from vegetable oils in “filled milk,” soft margarine, and straight-up soybean oil; by contrast, only 9 percent of fat calories came from vegetable oils in the control diet. (It’s worth noting, however, that those analyses were averages, and measured only the food each hospital provided—not the food the participants actually consumed from that selection.)

For those eager to vilify saturated fat, the trial’s results were a thing of much glory. Compared to the control-diet periods, the high PUFA periods triggered a hefty drop in total cholesterol—an average reduction of 12.8 percent for women and 15.5 percent for men.

More important, though, was the high PUFA diet’s association with heart health, at least for the study’s XY-chromosome crowd. While women didn’t see much benefit from PUFA loading in terms of cardiovascular outcomes, the men saw a whopping 44 percent decrease in their incidence of cardiovascular disease when they were eating a low-dairy-fat, high-vegetable-oil cuisine.

Yet amid the confetti-tossing and kazoo-blowing for what appeared to be a victory for the diet-heart hypothesis, a shadow lurked. An army of shadows, in fact—cast by the study’s unprecedented legion of flaws. Ultimately, the study was less a “win” for the diet-heart hypothesis and more a “fail” for the scientific method. For starters, turning a critical eye to the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial’s fine print, we can see the following:

And those weren’t the only pitfalls. Along with multiple design flaws, the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial left a few critical variables flapping in the wind, woefully uncontrolled. Let’s take a look at what the study detailed in its 1979 publication:

In short, the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial is a classic case of study gone bad. Of course, controlling people’s food intake for years at a time is no easy task—and the study’s investigators likely did the best they could with a tricky situation. In that sense, the study’s biggest problem isn’t that it’s imperfect, but rather, that it parades hopelessly under a banner of false advertising.

Among its many uncontrolled variables, wobbly design, lack of blinding, and multiple confounders, the study would’ve been ripped to shreds by the scientific community had it not played such an integral role in getting the diet-heart hypothesis off the ground. In fact, thanks to its dramatic pro-PUFA findings, it remains one of the most supportive trials ever conducted of that hypothesis—making it a shoe-in for meta-analyses and review papers supporting a link between saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and heart disease.

Even if the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial magically disappeared from our repertoire of studies, a second trial—another Nordic nugget—might slide into its spotlighted place: the Oslo Diet-Heart Study. First published as a doctoral thesis in 1966 with follow-up publications in 1968 and 1970, this study is, like its Finnish brother, widely cited as evidence that replacing saturated fat with PUFA-rich vegetable oils does a body good.32

But as we shall soon see, this trial has a serious case of mistaken identity. Aiming for secondary prevention, the study’s lead researcher, Paul Leren, set out to see if an intensive cholesterol-lowering diet could reverse heart disease. He enlisted 412 middle-aged men who’d previously suffered from a heart attack into the study, and randomized them into two groups: a control group who continued to eat their normal diets and an experimental group who were assigned a diet rich in vegetable oil, low in animal fats, and nearly void of dietary cholesterol. As might be expected, the experimental group’s PUFA intake skyrocketed to about 20 percent of total energy at the expense of saturated fat.33 And for five years starting in 1956, the men noshed away as directed.

At first glance, the high PUFA diet seemed to dazzle on the heart disease front. Along with slashing the experimental group’s total cholesterol by an average of 17.6 percent, the group suffered only ten fatal heart attacks during the study’s five-year run—compared to the control group’s twenty-three.

With that in mind, it’s no mystery why the Oslo study gets whipped out whenever the diet-heart hypothesis needs some cheerleading. On the surface, it looks like mighty fine evidence for swapping animal fats for vegetable oils.

But the study’s first write-up from 1966 reveals that the animal fat-vegetable oil swap was only the caboose in a much longer train of diet modifications. Let’s take a look at that original dissertation and see what this study really entailed.

As far as the control group went, there aren’t many bones to pick: the folks assigned to this group needed only to carry on with the standard, high-fat Norwegian diet of the time, with no guidelines or restrictions to heed. The only “new” thing in their bellies was a daily multivitamin, which all participants in the trial—whether control or experimental—received.

The high PUFA diet group, on the other hand, was saddled with a laundry list of demands stretching far beyond mere fat modification. (And to sweeten the deal while also boosting compliance, the group was showered with foodie freebies.) As outlined in the trial’s 1966 publication, the experimental diet was made up of the following:34

Let’s stand back for a moment and join hands for a critical thinking pow-wow and consider all the changes made to the control group’s diet.

Do you see the problem here?

Actually, the Oslo Diet-Heart Study was a pretty decent trial. Unfortunately, it’s not a trial that tested the diet-heart hypothesis. Trying to cite it as such doesn’t change that fact any more than claiming Elvis plays Texas Hold ’Em with you on Sundays makes him not dead. It just isn’t true.

Nonetheless, the study stands as a “landmark study”—towering alongside the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial—that supposedly bolsters the high PUFA, low-saturated-fat dietary recommendations (still pushed by the USDA and other health authorities today), while ignoring the other dietary variables included in the study.

Let’s now examine the study’s follow-up. After a five-year jaunt in the trial, the diets of the participants were no longer under the careful watch of researchers. Instead, the men were given some dietary tips to take to heart, and that’s it.

Those who had been in the high PUFA experimental group were advised to stick with the cholesterol-lowering diet they’d mastered during the previous years. And those who had been in the control group were told they might benefit from trimming some fat from their diet, but weren’t given a lick of guidance beyond that.

So essentially, all the men in the study were released back into the dietary wilderness and allowed to roam free, choosing to stick with the study’s diet—or not. By the time the eleven-year follow-up rolled around six years later, heart disease mortality remained significantly different between the two groups. Yet the difference in total mortality between them was less impressive—failing to meet any statistical significance (p= 0.35).

Without knowing how the men ate during those six post-study years (and whether the former PUFA group stuck with their learned menu or abandoned it), it’s impossible to draw any conclusions about the impact of the Oslo study on longer-term mortality. But the results of the follow-up raise questions about what the overall mortality trends were for those five years of intensive dietary changes—figures sadly unreported by Leren.

As we’ll see in a few other studies outlined in this chapter, rates of cancer mortality would become particularly valuable to examine.

The Oslo study wasn’t the last problematic diet-heart-testing creature in line, either. In 1969, the results of another study—this one spanning eight years and, like the Finnish Mental Hospital Trial, swapping saturated-fat-rich foods for polyunsaturated oils—were published in Circulation. And it sang a much more alarming tune.

Commonly known as the LA Veterans Administration Study, the trial studied 846 elderly men living in a veteran’s home where their food intake could be rigorously monitored (and, due to their age, the men were unlikely to pack their bags and vamoose mid-study).

While the control group received a standard American diet consisting of 40 percent fat with only a tenth of that fat being polyunsaturated, the experimental group quadrupled their PUFA intake at the expense of saturated fat.

Both groups maintained roughly the same total fat intake, only the experimental group cut their dietary cholesterol by nearly half. The diet breakdowns shaped up as follows on the next page.

Control group: 2496

Experimental group: 2496

Protein (grams per day)

Control group: 96.3

Experimental group: 97.4

Fat (percent of total calories)

Control group: 40.1

Experimental group: 38.9

Cholesterol (mg per day)

Control group: 653

Experimental group: 365

Polyunsaturated fat (percent of total fatty acids)

Control group: 10 (or 4 percent of total calories)

Experimental group: 39.5 (or a bit over 15 percent of total calories)

In addition to successfully controlling diet variables, the study had a number of other strengths.

Randomized? Check. The men were ushered into the experimental group or control group via randomization.

Double blind? Check. Neither the men nor the doctors evaluating their causes of death knew who received which diet.

But the study’s main weakness was that, despite the randomization process doing a stellar job of keeping baseline characteristics evenly matched between the control and experimental groups, a disproportionate number of smokers ended up in the control group compared to the experimental. Keep this in mind as we trek through the next few paragraphs, because—if anything—it predisposed the control group to less favorable health outcomes.

The first several years looked mighty promising for the high PUFA veterans—predictable, one supposes, if you follow food-pyramid wisdom. The cholesterol levels of the experimental group dropped by almost 13 percent—a reduction that held steady for the full eight years of the trial and would’ve knocked the socks off any cholesterol-leery doctor.

Likewise, the experimental group’s heart disease mortality sank relative to the control group’s. Had the control and experimental groups been locked in a literal race, the experimental group might be the hare: speeding out of sight from the tortoise and declaring a premature victory. But behind the scenes, something formidable was happening.

Despite the experimental group’s advantage on the heart disease front, their overall mortality was pretty evenly matched with the control group. That’s because despite dying less from heart disease, the high PUFA group was dying more from something else.

And it just so happened to be cancer.

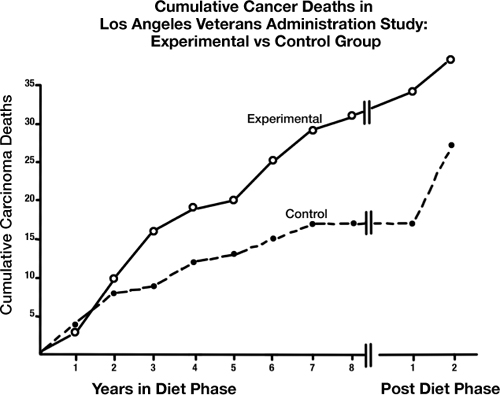

By the seventh year of the study, the high PUFA group’s cancer mortality took a sharp upward turn. In the eighth year, those deaths rose even more, with similarly striking speed. And in the ninth year? Oops, we don’t know—because that’s when the researchers, unaware of the surprising turn of events, ended the study.

Although the researchers didn’t realize what was going on until it was too late—losing the opportunity to see if cancer continued to rise in the group that was supposed to be healthiest had they extended the trial—they did realize the issue was too significant to ignore.

And thus was born another paper titled “Incidence of Cancer in Men on a Diet High in Polyunsaturated Fat,” published in The Lancet in 1971.37 In it, two of the study’s researchers, Morton Lee Pearce and Seymour Dayton, shift their focus away from the PUFA diet’s reduction in heart disease mortality and onto the disturbing excess of lives it claimed from cancer.

In describing the phenomenon, the researchers confessed their own surprise about what happened. “We anticipated that [the experimental group’s] deaths would be due to a variety of competing causes in these elderly men,” they explained in their paper. But the non-cardiac deaths weren’t evenly dispersed among those various causes. They wrote:

TABLE 6. Data from Morton Lee Pearce and Seymour Dayton, “Incidence of Cancer in Men on a Diet High in Polyunsaturated Fat,” The Lancet (1971). After two years on a high-PUFA diet, the experimental group saw an unexpected spike in cancer deaths that lasted throughout the study.

Subsequently we reviewed all our data with regard to deaths from causes other than atherosclerotic complications, especially when we read of experiments which association unsaturated-fat feeding with an increased incidence of spontaneous and induced neoplasms in animals.… We found a higher than expected incidence of carcinoma deaths in the experimental group.

With a p-value of 0.06, that finding was just on the cusp of statistical significance—not powerful enough to shout from the rooftops with conviction, but clearly pointing toward something important. And if the trial’s mortality patterns had continued moving in the direction they veered during the last few years of the experiment, the difference in cancer death rate may well have become even more compelling.

The cancer-based offshoot paper, though, added a new chunk of data as well: the two-year follow-up experience of returning the study’s surviving participants to their institution’s standard diet. The results here, too, were intriguing. For the first year after the trial ended and everyone resumed a fairly similar diet, the men who’d spent eight years on the high PUFA menu still saw a disproportionate rate of cancer mortality—four deaths compared to zero among men who’d been in the control group. But by the next year, that trend was gone, and the former-experimental-group’s cancer rate had dropped below that of the control group. The clustering of cancer deaths following high PUFA intake, with a carryover effect for about a year, was undeniable.

The researchers scoured their brains—and their data—in search of an explanation. But nary another factor could account for the rise in cancers clearly associated with the high PUFA group. Having exhausted all avenues possible with the information they’d collected, the researchers somberly concluded: “There is no apparent non-dietary explanation for the higher frequency of carcinoma deaths in the experimental group.”

One conundrum, which clearly left the researchers befuddled, was the fact that these findings seemed to contradict other data available at the time. The handful of similar studies that’d been completed by the early seventies failed to find increases in cancer deaths among high PUFA experimental groups.

Yet as the researchers explained, none of those studies had lasted as long as the LA Veteran Administrations trial. (And indeed, it wasn’t until the tail end of the study that the cancer trends became most alarming.)

Also, several of the seemingly disparate trials—for example, the Oslo Diet-Heart Study—were confounded by other dietary changes, another hadn’t published cancer data yet, and virtually all of the studies differed in terms of design and the type of folks under examination.

In the end, the study raised more questions than it brought answers. Would the PUFA-cancer connection keep gaining strength if the trial had lasted longer than eight years? What would happen if those participants had stuck with their high PUFA diets for one more year? Five years? Ten?

Unfortunately, we don’t know for sure—because there hasn’t been a single controlled study lasting long enough to find out. The only ongoing experiment, it seems, is the American public—and other Westernized populations with similar food trends—as we’re federally coaxed toward diets higher in PUFAs than the human body has ever experienced ever before in history.

Having been thoroughly alerted to the potentially nefarious role of PUFA’s, the AHA released a science advisory in 2009 titled “Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease.” It acknowledged other individuals and groups that recommended that people should reduce their omega-6 PUFA intake. The purpose of this advisory, the AHA stated, was “to review evidence on the relationship between omega-6 PUFAs and the risk of CHD and cardiovascular disease.”

Their conclusion was unequivocal. According to the AHA paper, the collective data from both human and animal studies shows that consuming 5 to 10 percent of total energy in the form of omega-6 PUFAs is not only healthy, but that “higher intakes appear to be safe and may be even more beneficial.” (Continued on page 178.)

TABLE 7. Information sourced from NutritionData.self.com.

In conclusion, they warned that reducing omega-6 PUFA intakes from what Americans already consume “would be more likely to increase than to decrease risk for CHD.”

Although the AHA tends to project an aura of cool objectivity, and their declaration of omega-6 safety might seem like the final word on the matter, there are a few reasons to question the paper’s validity. For starters, it’s worth taking a closer look at just who penned that report.

As noted in the paper’s “Disclosures” section, the lead author—William Harris—received significant funding from the bioengineering giant Monsanto, in addition to serving as a consultant for them. In fact, Harris had been hoisted aboard Monsanto’s research ship to study the company’s latest creation: an omega-3 enhanced soybean modified with genes from primrose flowers and bread mold.38

Shortly before the AHA released their omega-6 advisory, Harris published a study in Lipids showing that Monsanto’s engineered soybeans could boost omega-3 levels in the blood—while also supplying the ample omega-6 content.39 (Since then, Harris has authored additional papers supporting the benefits of Monsanto’s new soybean oil as a promising land-based alternative to marine oils.40,41)

Likewise, two additional authors of the AHA paper—plus all three of its reviewers—had received grants, been given other financial support, or served on advisory boards for places with a vested interest in PUFAs being healthful. Four of the authors and reviewers, in fact, had connections to Unilever—the maker of I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter and other margarines that serve as some of the highest sources of omega-6 fats in the Western world.

Of course, financial connections don’t automatically mean information is unreliable or biased beyond repair. Researchers have to get funding from somewhere, and often it’s corporations and other profitable entities willing to dish out that dough. Yet it’s hard to deny that producers of high-omega-6 foods would benefit from a major-league player like the American Heart Association endorsing—even indirectly—their products. And in the context of existing PUFA literature, the AHA’s kindness toward omega-6 fats does seem suspect.

Luckily, it was an oddity not lost on other scientists. After the AHA released their advisory, researchers from around the globe emerged to contest its conclusions. One commentary in the British Journal of Nutrition asked rhetorically whether the advisory was “evidence based or biased evidence,” pointing out that the AHA drew many of its omega-6 conclusions from studies that suffered major design flaws, were confounded by changes in omega-3 consumption, or otherwise failed to support the healthfulness of a high omega-6 intake specifically.42 The UK, in fact, had been warning for years that “there is reason to be cautious about high intakes of n-6 PUFAs,” going on to say that those whose diets already contain 10 percent or more of this fat shouldn’t play with fire by increasing it further.43

Other criticisms of the AHA’s omega-6 cheerleading abounded. Artemis Simopoulos—President of the Center for Genetics, Nutrition, and Health—also contested the AHA’s advisory, noting that the levels of omega-6 PUFAs currently in the American diet ought to be reduced, not held steady or raised. Explaining that humans had never in our existence experienced a diet high in omega-6 fats until the last fifty years or so, she called the modern omega-6 frenzy “an artificial way and a general experiment, being done without any scientific evidence.”44

In all, the AHA advisory cites a select few papers to support a positive view of PUFAs, while dismissing a larger body of work calling the safety of skyrocketing intakes into question. The advisory states: “In human studies, higher plasma levels of omega-6 PUFAs, mainly AA, were associated with decreased plasma levels of serum proinflammatory markers, particularly interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, and increased levels of anti-inflammatory markers, particularly transforming growth factor-β.”

In simple English, the advisory is basically saying that in the human studies they reviewed they found that the more omega-6 fatty acids in the blood, the fewer inflammatory markers in the body. To back up this statement, the advisory cites a single observational study from Northern Italy, in which the population—residents of the Rifredi district in Florence—had an average PUFA intake of only 2.9 percent of total energy.45 Considering that the US consumes closer to 7 percent, the Italian study is a stretch as evidence for the safety (much less benefit) of PUFA oils in a nation that consumes more than twice the amount. What’s more, the Italian study was conducted in a region where 99.6 percent of the population reported a staggeringly low total PUFA intake.46 Given all of that, why is the advice to consume plenty of vegetable oils—especially those rich in omega-6—still blasting in our ears?

First, from a health standpoint, PUFAs allure come from their cholesterol-lowering effect. They make lipid profiles look better on paper (at least in theory) and offer a sense of security matched only by statins. After all, lower your cholesterol to save your heart has become Western medicine’s oft-recited battle cry.

And second, vegetable oil is financially appealing. Since its very inception with Procter and Gamble back in 1912, polyunsaturated plant fats have indeed been unabashedly promoted as “healthy for the wallet” long before any “healthy for the body” arguments entered the scene. As unfortunate as it sounds, the budget-saving aspect may be PUFAs’ greatest appeal.

If increased oxidation caused by PUFAs really is as problematic as some argue, its effect may not be linear. For the sake of illustration, let’s imagine running a fairly villainous experiment where you give one person a bottle of cyanide to drink, and you give another person two bottles to drink. Even though Person B drank a doubled dose of poison, Person B won’t be any more dead than Person A, who drank a single dose. And Person B won’t be dead any faster—because both A and B still drank enough poison to elicit the maximum effect.

Likewise, in a realm industrialized vegetable oils, there comes a point where cell membranes simply cannot become any more saturated with PUFAs, no matter how many gallons of corn oil consumed. Increasing intake past the threshold—which is, quite possibly, a level the typical American diet has already met or exceeded—won’t do significantly more harm, because the damage is already maxed out.

For this reason, observational studies of Western nations are one of the worst ways to seek answers about PUFA consumption. Thanks to the nearly ubiquitous presence of high-omega-6 oils in our diet, even the lowest-PUFA eaters of the bunch may be consuming levels above that damage-causing threshold. The most compelling PUFA-related health changes won’t come until we can get our diets back down to normal levels, down to where they were at the turn of the twentieth century, before Procter met Gamble.