IN SEPTEMBER OF 2010, Bill Clinton—a slimmer, whiter-haired version of his former presidential self—sat down for an interview on CNN and divulged a story near to his heart, quite literally. After a quadruple bypass interrupted his book tour six years earlier, Clinton had found himself under the knife yet again: this time for two stents to prop open a vein that had already re-filled with plaque.

Once a proud connoisseur of chicken enchiladas and lemon chess pie, Clinton’s second hospital jaunt was enough to turn him onto a greener, leaner, more fibrous path. “I went on essentially a plant-based diet,” Clinton told CNN’s Wolf Blitzer. The former commander in chief described his new menu as an array of beans, legumes, vegetables, and fruits, with a plant-based protein supplement each morning thrown in for good measure. Recounting the research that inspired him to abandon his meat-loving ways, Clinton remarked:

So I did all this research and I saw that 82 percent of the people since 1986 who have gone on a plant-based diet—no dairy, no meat of any kind, chicken, turkey … 82 percent of the people who have done that have begun to heal themselves. Their arterial blockage cleans up; the calcium deposit around their heart breaks up.1

The impressive “82 percent” he cited—albeit out of context—came from Dean Ornish’s Lifestyle Heart Trial, the first study to show heart disease could actually be reversed without the use of drugs or surgery. Of course, the trial was also famously multifactorial—ushering participants through a slew of lifestyle changes ranging from stress reduction to exercise to smoking cessation. But just as we saw with the Pritikin program in the 1970s, it was the study’s near-vegan dietary component that cemented into public awareness.

Clinton was just one of a growing number of Americans nixing the USDA food pyramid’s already-spurned meat and dairy tier and replacing it with more vegetables, fruits, grains, and legumes. Indeed, one of the hottest contenders for the nation’s next dietary direction is the plant-based diet movement, which posits that better health will come from shifting the country’s menu even further plantward than federal guidelines have steered us.

The umbrella of plant-based eating encompasses everything from vegetarianism to veganism to more flexible whole-foods diets that simply keep meat, egg, and dairy intake as low as possible—options all united by the belief that plants are the best fuel for the human body. Of course, many people adopt vegetarian and vegan lifestyles for reasons other than health, including ethical considerations, religious or spiritual mandates, and environmental concerns. For our purposes here, I’ll speak chiefly from the nutritional perspective.

So apart from their snowballing popularity, are plant-based diets our best bet for helping the human body not just survive, but thrive? To answer this question, we need to pop back in time to look at how plant-based menus earned their “healthy diet” stripes in the first place. It’s not as straightforward a journey as you might think.

While vegetarianism has ancient global roots and a hard-to-pinpoint beginning on planet earth, we owe its birth in America largely to the Seventh-day Adventists, a twenty-four-million-member religion famous for its endorsement of healthful living and vegetarian eating. The church traces its roots back to the Millerite movement of the early nineteenth century—an American Christian sect that promised Christ would return on October 22, 1844, and left thousands of believers “sick with disappointment” when he was a no-show. After their savior’s failed return, which became aptly known as the Great Disappointment, a number of Millerites disbanded and faded into oblivion. But the loyal remainders recouped their loss by claiming the whole ordeal had stemmed from a scriptural misinterpretation. That group of believers would later become known as the Seventh-day Adventists.

Yet the Adventists’ health and diet message didn’t take shape until nearly two decades later, largely to the credit of one woman: Ellen Gould White. At the age of nine, White—a twin from a devout Millerite family—had been clobbered in the face by a stone from a rowdy classmate, knocking her into a three-week coma. Although the incident cut short her schooling and left her permanently disfigured, White eventually accepted her experience as the “the cruel blow which blighted the joys of earth” and turned her eyes toward heaven.2

Some critics suggest the accident left her with a traumatic brain injury and catalepsy, leading to seizures and hallucinations she would later interpret as divine prophecies.3 But White herself believed the experience was a fated step in the unfolding of her spirituality. Amid the bolt-from-the-blue visions that speckled her entire adult life, she claimed to channel health guidelines of divine origin—including not only edicts for adequate sleep, sunshine, rest, and social connection, but also for vegetarian eating and adherence to the Biblical dietary laws prescribed in Leviticus.

White’s first major vision about health gripped her on June 6, 1863—a moment she described as a “great light from the Lord,” in which she saw God’s people urged to abstain from all forms of flesh food.4 And as the years and visions rolled on, White increasingly saw meat as a threat to not only physical health, but spiritual health as well. In her 1926 publication “Testimony Studies on Diet and Foods,” she described meat as both an agent of disease and a thief of human empathy:

I have been instructed that flesh food has a tendency to animalize the nature, to rob men and women of that love and sympathy which they should feel for every one, and to give the lower passions control over the higher powers of the being. If meat-eating were ever healthful, it is not safe now. Cancers, tumors, and pulmonary diseases are largely caused by meat-eating.5

Likewise, White argued that the “sense of weakness and lack of vitality” people felt upon switching to a vegetarian diet was a good thing—proving, essentially, that meat was dangerously stimulating, and any strength it seemed to grant was of a dreadfully unholy nature.6 The visions were undeniable: meat, White was certain, should not pass through any God-fearing lips.

Although White’s prophecies became a cornerstone of the Adventist religion, it was one church member in particular who chiseled her message into the pages of American history. At a time when meat was widely regarded as a pillar for good health and a libido-booster in men, a fellow named John Harvey Kellogg hit the scene with a radically different perspective. Obsessed with physical purity, Kellogg—an Adventist born and raised—argued that, contrary to popular notions of his time, the road to health was paved with vegetables and celibacy. And he spent the majority of his life trying to convince the world of the same.

Fig. 13 John Harvey Kellogg, circa 1913, introduced some of the first packaged vegetarian foods, including soy milk and corn flakes.

The inspiration for his mission sprung forth in his youth. At age twelve, during the throes of the Civil War, Kellogg became an apprentice for Ellen White’s husband and learned the printing trade—which involved immersing himself in thousands of her vision-extracted words on health and the sanctity of the human body.7 Inspired by what he learned, Kellogg entered adulthood determined to convert health professionals to his meat-free, sex-free, violence-free ideals.

After earning a medical degree in 1875, Kellogg took over a tiny, Adventist-based medical center and transformed it into the Battle Creek Sanitarium—a spa-slash-health-clinic in Michigan that would eventually house twelve thousand patients at a time, including a celebrity lineup of prominent industrialists, politicians, and other major players in American society. Committed to whipping visitors into tip-top shape, Kellogg invented his own pieces of exercise equipment for the sanitarium’s guests to use. And perhaps more famously, he drummed up his own line of vegetarian convenience foods to help nurse visitors back to health—giving to the world, for the first time ever, items like granola, corn flakes, soymilk, and soy-based imitation meats. (His products eventually became property of the Kellogg Company, founded by Kellogg’s younger brother, Will Keith Kellogg.)

For decades, Seventh-day Adventism’s claim to fame was its transformation of the American breakfast. Meat was still on the menu, but suddenly crunchy cereals were, too, as were expanded options for plant-based foods where the animal kingdom once reigned supreme. Kellogg had failed to win the world over to his celibate, health-obsessed ways, but at least he had a part in filling some bellies with Cornflakes.

But the story doesn’t end there. The Adventists officially stole the spotlight not long after Kellogg’s passing, when their healthy lifestyles snagged the attention of the scientific community. While Ancel Keys fervently graphed the heart disease rates of various countries, other researchers set their sights on the Adventists, curious why they seemed spared from the chronic diseases plaguing the rest of the country.

Investigators first corralled Adventists into the science world in the 1950s with the launch of the twelve-year Adventist Mortality Study—a project that cranked out our earliest evidence of the Adventists’ relative protection against cancer and heart disease.8 Since then, two other major studies of the Adventist’s unique way of life have hit the scene: the Adventist Health Study 1 (AHS-1), which spanned from 1974 to 1988; and the Adventist Health Study 2 (AHS-2), which kicked off in 2002 and is still ongoing. Both offer further confirmation that as a group, the Seventh-day Adventists put the rest of America to shame in nearly every index of health.

One of the reasons the Seventh-day Adventists are such a hot commodity for observational research is that their lifestyles are, at least in theory, fantastically homogenous. Americans at large tend to hop, skip, and yo-yo from diet to diet; drink alcohol excessively or not at all; chain smoke or never smoke; and go to the gym only after pinning their New Year’s resolutions to the fridge for a month. That makes for some muddled, confounder-ridden population studies. But by default, the Adventists nearly avoid all those problems. Along with a strong nudge to go vegetarian, the Adventist church teaches its members to abstain from tobacco and alcohol, participate in physical activity, get sunshine and lots of fresh air, and prioritize family life and education (including health education). Adventists are also encouraged to stay away from caffeine, hot condiments, and hot spices. With such guidelines in place—and, for the most part, followed—the biggest area for wiggle room is in how an individual Adventist participates on the no-meat front. Some choose to do the bare minimum and abstain from just pork and shellfish, per the teachings of Jewish law outlined in the book of Leviticus. Others follow a stricter no-animal flesh diet as Ellen White urged.

Indeed, even within the Adventist population, stark differences emerge between folks of different meat-eating persuasions. One analysis found that Adventists following a true vegetarian diet consumed less coffee and doughnuts, and more tomatoes, legumes, nuts, and fruit than the more liberal meat eaters.9 Likewise, studies of Mormons—who also shun alcohol, tobacco, tea, and coffee, but whose founder never endured any meat-abstinence visions—suggest that they, too, enjoy far-above-average health like the Adventists. Starting in the 1960s and 70s, data emerged showing that Mormons had as little as half the cancer incidence and two-thirds the heart disease mortality of the surrounding population—even when their socioeconomic status, urbanization, and other quality-of-life markers were the same.10,11 Along with the to-be-expected reduction in cancers linked with smoking, Mormon females had significantly lower rates of breast cancer, cervical cancer, and ovary cancer, while both genders had a one-third reduction in rates of stomach cancer, colon and colorectal cancer, and pancreatic cancer.12,13

But what’s even more telling is the fact that meat-eating Mormons and vegetarian Adventists tend to live equally as long. When compared to ethnically matched folks outside their religious groups, both Adventist and Mormon men—once their birthday-cake candles start numbering in the thirties—can expect to live about seven years longer than the rest of the population.14,15

So what role does meat (or lack thereof) play in the Adventists’ longevity? We might never know for sure—but that doesn’t stop the media, and even well meaning researchers, from attributing the Adventists’ stellar health to their vegetarian ways.

Even among the non-Adventist population, it’s a tall order untangling the meatless component of plant-based diets from other entangled variables. Vegetarians, after all, rarely forego meat and call it a day. The decision to drop flesh foods often goes hand-in-hand with a cascade of other nutritional and lifestyle changes known to boost health. In the past couple decades, we’ve learned that vegetarians tend to exercise more, smoke less, limit alcohol, eat fewer refined grains, eat more vegetables, eat more fruit, eat fewer donuts, and engage in a variety of other behaviors existing independently of meat consumption.16,17 For vegans, who take vegetarianism one step further by eschewing eggs, dairy, and anything else derived from animals, the increase in positive lifestyle habits is even more dramatic.18

TABLE 8. Source: Maria Gacek, “Selected Lifestyle and Health Condition Indices of Adults With Varied Models of Eating.”

This raises the same question spurred by our studies on Adventists. What is it about vegetarianism that boosts health? Is it the reduction in meat, or the increase in beneficial plant foods? Is it a consequence of diet alone, or do other lifestyle modifications snowball into a giant glob of healthfulness that then tips chronic disease outcomes in a favorable direction? How does vegetarianism work its purported magic?

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have clear answers to these questions. The bulk of our vegetarian data comes from population studies—which, if you’ll recall, offer descriptive snapshots rather than razorsharp evidence. It’s simply not feasible—mainly for legal and logistical reasons—to conduct the type of widespread, labor-intensive, tightly controlled, and obsessively monitored experiments necessary to gauge how long-term vegetarian lifestyles fare next to identical ones that include meat.

But don’t take my word for it. A number of researchers lament this very problem, acknowledging that the benefits of vegetarianism, when they appear, are hard to trace to the exclusion of meat per se. In his 2003 review “The contribution of vegetarian diets to human health,” researcher Joan Sabaté—himself a vegetarian—remarked that the benefits of whole plant foods are “possibly more certain than the detrimental effects of meats.”20 Likewise, a 2012 review in Public Health Nutrition concluded that going vegetarian isn’t the only way to reap the benefits of certain plant foods: simply adding more garden-cultivated superstars to your diet will provide health benefits, regardless of whether you also eschew meat. What’s more, no evidence exists to support the idea that simply avoiding meat brings greater health benefits.21 At least in this case, it’s not so much what a diet avoids but what it generously includes. Let’s take a closer look.

As we’ve just learned, vegetarians, when compared to the general population, definitely seem to have a leg up in the longevity race. In fact, at least one vegetarian-dominated population has been crowned a “Blue Zone” because of its famed health and life spans: The Californian city of Loma Linda—home to one of the highest concentrations of Adventists in the US.22 It shares company with the citizens of Okinawa, Japan, and Sardinia, Italy, as a centenarian hotspot.

For some, this is enough evidence to hop on the veggie wagon. Yet the life-extending advantage of such a lifestyle gets hazy when you begin to draw similar comparisons with health-conscious omnivores. In a prospective study in Germany, researchers spent twenty-one years following almost two thousand vegetarians and their omnivore family members (who were assumed to have been at least partially influenced by the vegetarians’ health enthusiasm), only to discover little difference in mortality between the meat eaters and the meat avoiders.23

But here’s where it gets really interesting: despite a nonsignificant reduction in deaths from heart disease, the vegetarians actually had slightly higher rates of all-cause mortality and cancerous tumors than the omnivores—although both groups in the study fared much better than the German population at large.

And when the researchers divided the vegetarian group further into lacto-ovo vegetarians and strict vegans, veganism wound up with the highest mortality risk out of any group in the study. It was a 59 percent higher risk, in fact, than their omnivore brethren. (Given the relatively small number of vegans scooped into the participant pool—only sixty of them total—it’s hard to say whether that finding would’ve held up with a larger sample size, or if it was mostly a matter of random chance.)

Even more intriguing, the study failed to use omnivores that were truly equally matched with their vegetarian counterparts: the meat-eaters reported lower levels of physical activity, greater alcohol consumption, and more than twice the smoking frequency compared to the study participants who ate no meat. Mortality and disease rates, in this case, might be expected to turn up in favor of the vegetarian crowd, even though the opposite ended up happening.

And Germany isn’t the only seat of such trends. The Health Food Shoppers Study, which followed nearly eleven thousand health-conscious omnivores and vegetarians in the United Kingdom over the course of twenty-four years, found no difference in overall mortality between those who ate meat and those who didn’t.24 Among specific causes of death, the only significant finding was a considerably higher rate of breast cancer mortality among the vegetarians (a death rate ratio of 1.73—or 73 percent greater—in vegetarians compared to meat eaters). That finding had also popped up in an earlier analysis of the cohort, and the study’s investigators suggested it could be related to the fact that British vegetarian women were somewhat more likely to stay childfree. A similar study had found that 37 percent of middle-aged female vegetarians had never given birth, compared to only 28 percent of omnivores.25 Given that childbearing is protective against breast cancer, it’s possible vegetarian women’s tendency to produce fewer offspring put them at greater risk for the disease.26 Whether that was enough to explain the higher death rate among vegetarians remains speculation, though.

Similarly, the Oxford Vegetarian Study—which surveyed over eleven thousand vegetarians in the UK, along with their potentially health-savvy friends and relatives—found zero difference in overall mortality between the vegetarians and omnivores over a twenty-year span.27 As with the Health Food Shoppers Study, only one specific death-cause reached significance: mortality from mental and neurological diseases, which was 146 percent higher among vegetarians than their non-vegetarian kin. (Considering there were only thirty-six deaths from this category in the whole cohort, though, that statistic is probably worth taking with a grain or two of salt; the smaller the sample size, the greater the danger of false or exaggerated trends emerging.)

As a whole, the only vegetarian population with consistently better health outcomes than omnivores comes from the Seventh-day Adventists—an indication that lifestyle factors other than diet are running the show.

Could it be that, as a group, vegetarians fail to dazzle the lifespan charts because they’re still eating plenty of eggs and dairy? If you’ve been traipsing through the health world for any length of time, you might have seen that argument before—especially if you’ve come across popular books like The China Study, the 2011 documentary Forks Over Knives, or others in the long line of resources promoting total or near-total exclusion of animal products. According to this line of thinking, the only necessary—and appropriate—amount of animal products for the human body is zero. Welcome to the world of veganism.

As we saw earlier with Bill Clinton, a number of other famous people (who, for better or worse, are one of the best barometers of a diet’s popularity) have hopped on the plant-based bandwagon.28 But even for those deaf to celebrity endorsements, veganism seems to be gaining legitimacy as a tool for disease reversal, longevity, and overall well-being. A group of whole food, plant-based diet doctors—including John McDougall, Neal Barnard, Caldwell Esselstyn, Dean Ornish, and Joel Fuhrman—have had impressive success using their protocols to treat a variety of health conditions, most notably heart disease and diabetes.29,30,31,32 It’s no surprise, then, that such successes lend some weight to the argument that veganism—or the closest thing to it that we can muster—is the optimal diet for humans.

Unfortunately it’s not quite so simple. As often happens with any switch from industrially processed products to whole, natural foods, there’s more to the story than the mere elimination of animal products. All existing trials of disease-slaying vegan or near-vegan diets involve reducing or eliminating refined grain products, sugar, high fructose corn syrup, industrially processed vegetable oils, soft drinks, and most other heavily processed foods. Some, like the Lifestyle Heart Trial that put Ornish’s name in the books, also include stress reduction, smoking cessation, peer support, exercise, and other modifications that have nil to do with diet. When these studies show success, it’s impossible to determine which variables were the ones influencing the outcome. In a word, such studies are confounded.

A common argument for choosing plants over animals comes from looking at the diet of our furry, opposable-thumbed primate cousin: the chimpanzee. Sharing about 98 percent of our DNA, chimpanzees are one of our closest genetic relatives—tied only with the fruitnoshing, free-loving, remarkably promiscuous bonobos, who make up the other half of the genus Pan.33

While a nontrivial portion of the chimp diet consists of insects, eggs, and the occasional hunted mammal, chimps certainly aren’t mowing down on large quantities of meat. Indeed, the majority of their diet is plucked from trees and bushes and shrubs.

Does our own anatomy suggest similar herbivorous leanings? Some argue for a “yes.” For instance, Vegsource.com—one of the world’s largest and highest-trafficked vegetarian websites—cites humans’ muscular lips and tongue, flattened mandibular joint, large and tightly aligned teeth, narrow esophagus, moderately acidic stomach, long small intestine, and pouched colon as evidence that we have the anatomy of a “committed” herbivore—with a gastrointestinal tract “designed for a purely plant-food diet.”34 Similar arguments abound from vegetarian authors and in other vegetarian resources, depicting the human body as a plant-powered machine that inevitably suffers if it consumes other animals.35,36

Yet the truth about human anatomy is far more complex. In her paper “Nutritional Characteristics of Wild Primate Foods,” Katharine Milton—an anthropologist specializing in the digestive physiology and dietary habits of both human and non-human primates—outlines some of the changes we’ve undergone over the course of our evolution.37 It turns out that our digestive tracts, while far from being akin to those of true carnivores, feature some adaptations that point to a likely role of meat.

According to Milton, humans do share some basic digestive anatomy with other primates, thanks to the beauty of our evolutionary history. Despite splitting from our last common ancestor with chimpanzees—Hominini—somewhere between four and seven million years ago, we have the same basic gut anatomy as the apes who still roam the jungles: a simple, moderately acidic stomach; a small intestine; a small cecum; an appendix; and a sacculated colon full of numerous, tiny pouches. With a cursory glance, the “humans should eat like the other primates” argument might seem to hold water.

But the noteworthy differences come when we look at gut proportions. As Milton explains, over half of humans’ total gut volume is found in the small intestine—in sharp contrast to other apes, whose capacious colons dominate their digestive systems. In fact, in primates like chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, the colon is about two to three times the size of the small intestine, while the human colon is about half the size of our small intestine.

So what does that mean for diet? In simple terms, a big colon is good for handling “low-quality” foods like tough leaves, stems, twigs, bark, fibrous fruits, and other plant matter that requires a lot of digestive toiling to break down.

TABLE 9. Relative volume of the stomach, small intestine, cecum, and colon for six species of primate: gibbon, siamang, orangutan, gorilla, chimpanzee, and human. Humans possess notably less gut volume in the colon and more in the small intestine compared to other primates. Adapted from Dr. Katharine Milton’s 1999 article, “Nutritional Characteristics of Wild Primate Foods.”

Primates that thrive on greens have a massive army of microbes in their colons that can effortlessly digest fiber and convert it into short-chain fatty acids via “hindgut fermentation”—meaning that, unlike humans, they don’t choose the salad just to keep their svelte figures. Although humans have some capacity to ferment fiber in our colons and derive energy from it, we’ve lost the ability to do it with much efficiency. The hindgut volume in apes is around 52 percent; in humans it’s shrunk to a measly 17 to 20 percent.38 Gorillas, for instance—professional hindgut-fermenters that they are—can get a whopping 57 percent of their calories from all the fiber fermentation happening in their colons.39 Humans would starve (or go insane from stomach gurgles) trying to do the same.

As Milton explains, humans shouldn’t try mimicking primate diets. In her own words, “certain features of modern human gut anatomy and physiology suggest that such dietary habits probably would not now be feasible.” While the dominance of the hindgut in our primate cousins suggests they’re adapted to diets that are bulkier and more fibrous than what modern humans eat, our own small-intestine dominance suggests we’re adapted to foods that are dense, highly digestible, and don’t take a massive microbe attack to break down—such as animal products and cooked foods.

There are, of course, some remaining unknowns. When exactly in our evolutionary history did our colons become dwarfs of their ancestral selves? What provoked the human gut to change from a colon-dominated, fiber-fermenting vat of microbes capable of handling tough plant fare, to the relatively wimpy system we have now—where we need an elite diet of soft and dense foods in order to thrive? Since the earth isn’t exactly littered with perfectly preserved digestive tracts from millions of years ago, it’s tough to answer these questions. What we do know is that numerous archeological sites suggest an increasing role of animal foods, including shellfish and scavenged animals, throughout the last several million years of our history. Unlike fibrous plant matter, those foods require very little colon action and could easily have influenced its shrinkage in our modern bodies.

The evolutionary diet of humans is hard to gauge anatomically for two other reasons as well. For one, our digestive systems have—in some sense—atrophied due to our reliance on cooking and external processing to “pre-digest” the things we eat, whether those foods come from the plant or animal kingdom. (Even in those barbaric days before the George Foreman Grill and Vitamix, we at least had fire pits and hammerstones.) And secondly, we’ve co-evolved with tools to such a degree that we’ve rendered claws, tails, and sharp teeth nearly useless, making these ineffectual markers for discerning our dietary adaptations.

Despite the remaining questions, though, it’s pretty clear that we can’t draw a dietary parallel between humans and our primate relatives based on our digestive anatomy. Simply put, we humans cannot subsist on leaf and twig alone.

On paper, meeting your nutritional needs without animal products seems simple enough. More dark, leafy greens for calcium. Fortified foods or supplements for B12. Sunshine for vitamin D. Maybe some flaxseed for those essential fatty acids. Even from mainstream sources, we’re often told that’s the gist of what it takes to stay healthy on a diet free from (or at least very low in) animal-based foods—and as long as we meet our nutrient targets on paper, we’re good to go. In practice, though, the nutritional adequacy of veganism is neither clear-cut nor universal.

The reason some people seem to thrive on plant-based cuisines while others struggle has much to do with our fabulous diversity—particularly how we metabolize and convert plant-based nutrients, a fate resting largely in the hands of genetics (go ahead and blame your parents for that one). Here’s a rundown of the nutrients some portion of the population will struggle to glean from plant foods alone.

Vitamin A: This nutrient is one of the biggest potential absentees as far as plant-based diets go. But what about carrots, sweet potatoes, and leafy greens, you ask? It’s actually a popular misconception that these plant-based foods are vitamin A powerhouses.

“True” vitamin A exists only in animal foods. Plants, on the other hand, feature an array of carotenoids, more than six hundred different types, of which about fifty, including beta-carotene, will convert to the usable form of vitamin A in your body. Well, at least in theory.

Here’s the problem: the carotenoid-to-vitamin-A conversion rates vary tremendously from person to person, and not everyone can squeeze enough vitamin A out of plant foods to stay healthy. Some folks inherit gene alleles that dramatically reduce the body’s ability to convert carotenoids, and in other cases, problems such as liver diseases, food allergies, celiac disease, parasite infection, H. pylori infection, and deficiencies in iron or zinc can put a major damper on the carotenoid conversion process.40 As a result, good converters of carotenoids might breeze through a plant-based diet with no vitamin A troubles, whereas a poor converter may experience a gradual onset of deficiency symptoms—often beginning with skin problems, poor night vision, and infertility.

Vitamin B12: Despite the occasional rumor to the contrary, there are no reliable, naturally occurring sources of vitamin B12 in plants. Some seaweeds, commonly mis-cited as bestowers of B12, actually contain B12 analogues that won’t actually improve your true B12 status.41 But virtually every study conducted on the subject shows that vegans experience much higher rates of B12 deficiency than omnivores or vegetarians, and have elevated homocysteine as a result, which increases blood clotting and may raise your risk of heart disease. In fact, low B12 and high homocysteine may very well have contributed to the early demise of prominent vegans like H. Jay Dinshah and T.C. Fry, both long-term adherents of their vegan diets who passed away before their time.

Vitamin K2: Although it tends to get lumped in with vitamin K1 with regrettable frequency, vitamin K2 is in a class of its own. Woefully unknown to the public and mainstream health experts alike, vitamin K2 is critical for a healthy heart and skeleton, working synergistically with other fat-soluble vitamins and some minerals.

Among other things, it helps shuttle calcium out of your arteries (where it contributes to plaque formation) and into your bones and teeth, where it rightfully belongs. Unlike vitamin K1, which is abundant in some vegan foods like dark leafy greens, vitamin K2 is only found in certain bacteria and animal products such as dairy (especially hard cheeses and butter), organ meats, eggs, and fish eggs. The only abundant vegan source is natto—a not-always-appetizing fermented soybean product that contains K2-producing bacteria. Other fermented vegetable products, like sauerkraut, can contain some K2 depending on the type of bacteria they contain.

Omega-3 fats, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA): If you’re a vegan, your main source of these essential fatty acids is through your body’s conversion of their precursor, alphalinolenic acid (ALA). However, a number of dietary and genetic factors influence how well your body makes that conversion—leaving the potential for DHA and EPA insufficiency, even if you have a decent intake of ALA from flaxseed and other vegan foods.

The hallmark of many plant-based diets is not just the acceptance of starch, but the warm embrace of all things whole-grainy and tuberous. In fact, the pro-starch message is reverberating loudly outside the walls of the USDA, entering the realm of esteemed plant-based diet doctors like Dr. John McDougall. But America’s amber waves are no joke.

While a boon for many farmers (and, in its current subsidy-soaked state, the economy), this advice sweeps individual starch tolerance under the rug, with tragic consequences. Just as Luise Light predicted many years ago, a mass prescription of starch-centrism for the country has failed to restore America’s health, especially when guidelines are so lenient with “junk” carbohydrates. Obesity and diabetes have only continued to soar. And vegetarianism—as it’s typically practiced today—tends to share the USDA pyramid’s unconditional emphasis on grains, often flying its starch emphasis under the banner of healthfulness.

While some people may thrive on a diet higher in starch, mounting research shows that it wreaks havoc for others. And the evidence is far beyond anecdotal. It turns out some of us are genetically blessed with better starch tolerance than others—a fact that should be acknowledged in any guideline that tries to steer us toward good health. When it comes to vegetarian eating in particular, the narrower range of food groups can lead to an even greater emphasis on starches.

Your saliva might seem uneventful and slimy, but it’s actually a pretty happening place. In fact, it’s teeming with all sorts of proteins that kick off the digestion process—including alpha-amylase, an enzyme that breaks down starch into sugar. If you’ve ever held a cracker or piece of bread in your mouth and witnessed it miraculously turn sweet, that was your amylase in action, chopping up all those bland starch molecules into tasty sugars. (Even after you swallow, amylase remains hard at work: partially digested starch protects amylase from getting deactivated by your stomach acid, so any amylase-riddled globs of potato, rice, noodles, or other starchy foods you’ve chewed up can continue their journey onto becoming sugar molecules even after entering your belly.42)

In order to furnish the mouth with starch-digesting proteins, we all carry copies of a gene called AMY1, which encodes the salivary amylase enzyme. Indeed, amylase is a gem some plant-based diet advocates cite as evidence for a starchy diet being optimal for mankind. In his book The Starch Solution, McDougall discusses human amylase status as evidence that we are, as a species, genetic starchivores:

Studies of the gene [AMY1] coding for amylase … found that humans have on average six copies of the gene compared to two copies in other, “lesser” primates. This difference means that human saliva produces six to eight times more of the starch-digesting enzyme amylase.… It was our ability to digest and meet our energy needs with starch that allowed us to migrate north and south and inhabit the entire planet.43

Just one problem: it’s not that simple. It turns out the number of AMY1 copies contained in our genes is not the same for everyone. And the amount of salivary amylase we produce is tightly correlated to the number of AMY1 copies we inherited. In humans, AMY1 copy number can range from one to fifteen, and amylase levels in saliva can range from barely detectable to 50 percent of the saliva’s total protein.44 That’s a lot of variation!

Where you land on the amylase spectrum is more than just luck of the draw, too. Folks from traditionally starch-centric populations, like the Japanese or the Hazda of Tanzania, tend to carry more copies of AMY1 than folks from low-starch-eating populations, like Siberian pastoralists or hunter-gatherers from the Congo rainforest.45 One analysis found that nearly twice as many people from high-starch populations carried six or more copies of AMY1 (considered the average number for humans) compared to folks from low-starch populations.46 Since AMY1 copy number varies greatly among different groups within the same region, it’s clear that traditional diet has a greater influence on this gene than simple geography.

The reason for such vast variation is rooted in the nutritional pressures that clobbered us throughout history. For populations whose food staples were starches, such as roots and tubers and grains, carrying more copies of AMY1—and packing more amylase in their saliva as a result—would have been a major boon for survival. Those best able to metabolize starches, in those cases, would be the healthiest and strongest. Their genes would muscle their way into dominance.

On the flip side, populations relying more on animal foods and non-starchy carbohydrates from fruit, honey, or milk wouldn’t face much selective pressure for amylase production. In those populations, folks with less starch-digesting power would be at no disadvantage to those with more. Those with fewer copies of AMY1 would remain warmly embraced in the gene pool, with other adaptive pressures taking precedence over starch tolerance.

The same pattern holds true for our closest genetic relatives. Non-human primates that rely on starchy plant matter produce significantly more amylase than species like the chimpanzee and bonobo, who favor ripe, low-starch fruit.47,48 As a result, chimpanzees universally carry only two copies of AMY1, and the closely related bonobos all carry four—similar to humans from starch-sparse populations.49

What’s more, the lack of variation in gene copy number in all primates except humans emphasizes the quirkiness of our diet history. While other primates embrace a pretty consistent menu within their species, humans have endured impressive dietary diversity since we’ve split from our last common primate ancestor—a legacy that’s stamped its mark all over our genome.

So what happens when low amylase producers encounter, say, a heaping pile of pasta? Do their bodies simply escort it out like an ID-checking bouncer at a club, throwing it back from whence it came before it can do any damage? Not quite. It turns out that for folks without amylase-supercharged saliva, feasting on starch might have dire consequences for blood sugar and insulin levels—calling into question the USDA’s wisdom in prescribing a starch-based diet for the entire nation.

Researchers at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia wanted to learn why and conducted a groundbreaking trial on starch tolerance.50 Their study looked at blood sugar and insulin responses to starch consumption among high-amylase producers versus their low-amylase counterparts—the first time anyone had actually investigated whether there might be a difference. The participants were all healthy, normal-weight, mixed-race adults with significantly higher or lower salivary amylase than average.

Each subject came into the laboratory twice, for two different feedings: one using 50 grams of pure glucose and the other using 50 grams of cornstarch hydrolysate. After each session, the participants hung around for two hours and had their blood sugar and insulin levels monitored. As seemed logical, the researchers thought the high-amylase participants would have the strongest blood sugar response from eating starch, seeing as they’d be breaking it down into sugar molecules more efficiently.

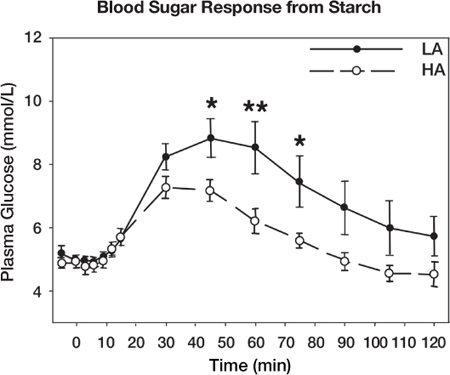

But the human body, the infinite wonderland that it is, had a surprise in store, and the study took a fascinating turn. The results—published in the Journal of Nutrition in 2012—showed that low-amylase producers faced skyrocketing blood sugar after eating starch, in contrast to the less dramatic rise seen among high-amylase producers. The paper included a graph capturing the trend. (See Table 10.)

TABLE 10. This table shows the differences in blood sugar (plasma glucose) levels after consuming pure starch for low amylase producers (LA) versus high amylase producers (HA).

After about fifteen minutes, the low-amylase group (represented by the top line with black dots) started leaving the high-amylase group in the dust, at least as far as blood sugar was concerned. Not only did their levels peak at about 2 mmol/L (or 36 mg/dL) greater than the high amylase group, but the profound difference continued all the way to the end of the two-hour monitoring phase, and likely persisted well beyond that. Simply put, the low-amylase group’s blood sugar rose higher and stayed higher for a shockingly long time.

When the procedure was repeated using glucose, though, the results were a different story. Folks with low amylase levels saw an overall milder response than they did with starch—with blood sugar dropping back to normal levels more quickly and not diverging much from the high-amylase group. If anything, that suggests low-amylase producers might actually have better tolerance of sugar than they do of starch—a conclusion that could and should send shockwaves through modern dietary recommendations that tend to treat sugar as the only offensive carb of the bunch while hurling starch atop a high and mighty throne.

Can you see why crowning starch as king of the food groups has likely done immeasurable damage to our health? Even today, half of our grain intake comes from refined sources per USDA guidelines. And the people who come up on the short end of the breadstick are are the low-amylase producers.

In fact, the study’s researchers warn that such individuals “may be at greater risk for insulin resistance and diabetes if chronically ingesting starch-rich diets”—raising the possibility that AMY1 gene copy may play a role in who succumbs to obesity and diabetes and who is graciously spared. And if that’s the case, perhaps AMY1 should be considered an important new risk factor for such conditions. The researchers even proposed putting the study’s findings into clinical use by screening individuals for low AMY1 gene copy number, thus equipping patients with knowledge about their risk—and hopefully thwarting disease before it strikes.

We haven’t pinpointed when exactly our ancestors started accumulating more AMY1 copies and revving up their starch-metabolizing capabilities. But the adaptation may be at least partially grain related—especially seeing as agricultural populations universally carry AMY1 copy numbers on the higher end of the spectrum. (Prior to domesticating grains, humans may have started facing selective pressure for AMY1 with the control of fire—at which point hard, starchy, barely edible roots and tubers could be softened with heat and turned into exciting new calorie sources.)

For Americans struggling to conform to dietary guidelines in order to boost their health (as well as vegetarians embracing a similarly starch-centric pyramid), the amylase issue spells trouble in a big way. Imagine entering a rowing race where half of the participants can use oars and half must paddle wildly with their hands. It wouldn’t be long before wails of unfairness echoed through the crowd and riots ensued, right? Being a high-amylase producer offers a similar game-changing advantage, at least when the waters we’re sculling through are filled with starch. In a population where some people have nearly eight times as many AMY1 copies as others, and saliva can range from amylase-replete to amylase-barren, prescribing a starchy diet to the entire population is a recipe for disaster. Those at a metabolic disadvantage will always be left flailing near the shore, unable to keep pace with the rest. By ignoring individual variation regarding starch tolerance, promoters of high-starch diets for every human being do our collective health a disservice.

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so hopefully the vegetarian movement will feel honored when omnivores skim some of the pro-health foam off the top of vegetarianism without going as far as totally avoiding meat. Here are a few tips: