There is only one type of story in the world — your story.

— Ray Bradbury

In Woody Allen’s movie Annie Hall, there is a passing conversation between some players at a fancy Hollywood party. One guy says, “Right now it’s a notion, but I think I can get money to turn it into a concept … and later turn it into an idea.”

As with all satire, the scent of truth lurks underneath. Before your plot exists, it is a notion you have. A spark, which at some point ignites. But it is here where many stories are doomed from the start. Not every idea is of equal value. To find the best plots, you need to come up with hundreds of ideas, then choose the best ones to develop.

That’s what this chapter is about.

And before you jump into the top twenty ways to get plot ideas, you need to spend some time on the person who is going to turn them into fiction gold — you.

That’s where you start in finding plots.

William Saroyan, whose novels have more passion in them than most, was once asked the name of his next book. “I don’t have a name and I don’t have a plot,” he replied. “I have the typewriter and I have white paper and I have me and that should add up to a novel.”

That’s why Saroyan’s work seems so fresh. He was not content with the old advice, write what you know. He figured out early that the key to originality was write who you are.

Fiction writers, especially those who write to inspire, should follow Saroyan’s example. By going deep into your own heart and soul, you will find a wellspring of ideas to write about. Moreover, your writing will come alive, and your stories will have the chance to truly move your readers.

A word of caution, however. To write who you are does not mean producing a fictionalized autobiography. All writers have one autobiographical novel inside them, and that’s usually a good place to leave it. These days publishers are wary of autobiographical novels because the prospects of turning them into good sellers are practically nil.

The market wants gripping fiction without clichés, standard characters, or tired plots. And the key to satisfying this market, to making your fiction sing with originality, is to write who you are.

All writers should periodically take a good look inside themselves. Before developing your next plot, take some time to answer the following questions. This will create what I call a “personality filter” through which you’ll be able to generate original plots full of interesting characters:

Answering these questions opens up a door into your own soul. From that viewpoint, you can better evaluate plot ideas. Does the story you’re considering hit a nerve inside you? If not, why write it?

“Know thyself,” the sages admonished, and that’s still good advice. Especially for writers. By knowing yourself truly and honestly, by writing with passion and intensity, by caring about important issues, you’ll find your writing is not only fresh, but a joy. You’ll have you. And that’s enough to start writing.

Not every idea is worth writing about. Why spend six months, a year — ten years! — hammering out something that editors and agents, not to mention readers, will not care about?

Listen: You haven’t got time to waste on mediocre stories.

So what do you do? How do you come up with an idea so good that it alone is almost enough to keep readers reading?

In school, I was taught to sit and think and formulate an idea, then set to work.

That’s the path to the reaction, “I’ve seen this before.”

You need to do the opposite.

You need to come up with hundreds of ideas, toss out the ones that don’t grab you, and then nurture and develop what’s left.

In a moment, I am going to give you twenty ways to come up with hundreds of ideas for your fiction. But first, some rules:

[1] Schedule a regular idea time. Once a week at least.

[2] Get yourself into a relaxed state, in a quiet spot where your imagination can run free.

[3] Give yourself thirty minutes of uninterrupted time.

[4] Select one or more of the exercises below. Read the instructions.

[5] Begin by letting your imagination come up with anything it wants to, and record everything on paper (or the computer).

[6] The most important rule: Do not, I repeat, do not censor yourself in any way. Leave your editorial mind out of the loop. Just let the ideas come pouring out in any way, shape, or form they want to. Do not judge anything.

[7] Have fun. Lots of fun. You’re even allowed to laugh.

[8] Save all your ideas.

[9] After two or three sessions, it’s time to assess your ideas. Use the guidelines in “Nurturing Your Ideas” at the end of this chapter.

[10] Repeat the process as often as you want.

And always remember: The journey of a thousand miles requires plenty of snacks. So feel free to eat while you do these exercises.

Here are twenty fast, simple, and fun ways to develop your own unique plot ideas:

This is perhaps the oldest, and still the best, creative game for the novelist. Originality is nothing more than connecting familiar elements in unfamiliar ways. The what-if game gets our minds thinking in such a way as to make those connections.

The what-if game can be played at any stage of the writing process, but it is especially useful for finding ideas. Train your mind to think in terms of what-if, and it will perform marvelous tricks for you.

For example, when you read something interesting, ask yourself, “What if?” Let all sorts of connections burst forth.

For one week do the following:

Make up a cool title, and then write a book to go with it.

Sound wacky? It isn’t. A title can set your imagination zooming, looking for a story.

Titles can come from a variety of sources like poetry, quotations, and the Bible. Go through a book of quotations, like Bartlett’s and jot down interesting phrases. Make a list of several words randomly drawn from the dictionary and combine them. Story ideas will begin bubbling up around you.

Take first lines from novels and make up a title. Dean Koontz’s Midnight begins, “Janice Capshaw liked to run at night.”What might you do with that?

Perhaps something like these: She Runs by Night. The Night Runner. Runner of Darkness. Night Run.

Now all you have to do is choose one and write a novel to go with it. It’s easy.

Early in his career, Ray Bradbury made a list of nouns that flew out of his subconscious. These became fodder for his stories.

Start your own list. Let your mind comb through the mental pictures of your past and quickly write one- or two-word reminders. I did this once, and my own list of more than one hundred items includes:

Each of these is the germ of a possible story or novel. They resonate from my past. I can take one of these items and brainstorm a whole host of possibilities that come straight from the heart. You can do the same.

What issues push your buttons? Robert Ludlum once said, “I think arresting fiction is written out of a sense of outrage.” Outrage is a great emotion for a writer. So start an issues list. You might include:

The late Edward Abbey based his novels on issues he cared about. For him, writing was a calling as well as a craft, which is one reason his books inspired a wide readership. The writer, Abbey believed, must be a moral voice. “Since we cannot expect truth from our institutions,” he wrote, “we must expect it from our writers!”

So one way to write who you are is to find the issues that press your hot buttons, then press them!

If you embody your moral viewpoint in a three-dimensional character who takes vigorous action to vindicate his cause, you’ll virtually guarantee a story packed with emotion and dramatic possibilities. Want that in your fiction? Then do this:

Remember, however, that fiction is not a sermon. Your job is to deliver a gripping story, not a windy lecture.

Let your imagination play you a movie:

Sit down first thing in the morning and ask yourself, “What do I really want to write about at this moment in time?” List the first three things that come to your mind. This may take the form of issues (crime in the streets, euthanasia, lawyers, religion) or characters (a character who shows guts in the face of danger) or situations (what if somebody got stuck in a blimp over Iraq?). Pick the one that gets your juices flowing the most.

Close your eyes and start the movie. Just sit back and “watch.”What do you see? If something is interesting, don’t try to control it. Give it a nudge if you want to, but try as much as possible to let the pictures do their own thing. Do this for as long as you want.

Then start writing, with no thought about plot construction, and keep writing for twenty minutes. Write about whatever you remember from the “movie.” You can make notes about character, plot ideas, themes, whatever. Just write. Do this every day for five days, adding to your written material each day.

Take a day off, then print a hard copy of your movie journal. Look it over and highlight the parts that turn you on. Go through the nurturing process now and apply the freshness test.

Music is a shortcut to the heart. Listen to music that moves you. Choose from different styles — classical, movie scores, rock, jazz, whatever lights your fuse — and as you listen, close your eyes and see what pictures, scenes or characters develop.

When you do find something worth writing about (and you will), you can use that piece of music to put you in the mood every time you sit down to write.

Perhaps the best and fastest way to get a story idea is through a character. The process is simple: develop a dynamic character, and see where he leads.

There are a variety of ways to come up with an original character. Here are a few:

If Shakespeare could do it, you can too. Steal your plots. Yes, the Bard of Avon rarely came up with an original story. He took old plots and weaved his own particular magic with them.

Admittedly, that’s harder to do today. You can’t lift plot and characters wholesale and pretend it’s an original story. But you can take the germ of another plot and weave your particular magic with it. You can switch key characters and conventions (see “Flipping a Genre” listed next). You can follow the same story movements even as you add your own original developments.

“Originality,” says William Noble in Steal This Plot!, “is the key to plagiarism.” What he means is you cannot lift the exact plot, with the same characters intact. But you may take a pattern (and plot is nothing more than a story’s pattern) and use it.

All genres have long-standing conventions. We expect certain beats and movements in genre stories. Why not take those expectations and turn them upside down?

It’s very easy to take a Western tale, for example, and set it in outer space. Star Wars had many Western themes (remember the bar scene?). Likewise, the Sean Connery movie Outland is like High Noon set on a Jupiter moon. The feel of Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man characters transferred well into the future in Robert A. Heinlein’s The Cat Who Walks Through Walls.

Even the classic television series The Wild, Wild West was simply James Bond in the Old West. A brilliant flipping of a genre that has become part of popular culture.

So play with genres, conventions, expectations. Mix them up. There is an idea there somewhere.

Novels can be “hot” because of the subject matter alone. If you are able to catch a topical wave before it breaks, you may have a winner.

The trick, of course, is in predicting what will occupy the popular mind. How can you do it?

The best source is specialty magazines. Often you’ll get a window into the immediate and long-term future areas of interest to people.

This doesn’t need to take a lot of time, either. Go to a newsstand and irritate the manager by scanning magazines like Scientific American, Popular Mechanics, Wired, Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News & World Report. In addition, USA Today often has stories about cutting-edge technologies and issues. Jump on something interesting and ask:

Read newspapers. Scan all the sections. Have your homing device set for sparks that get your mind zooming in original directions.

Read USA Today. The paper is written in “arrested attention span” style — lots of little snippets you can scan quickly. One edition will yield at least a dozen possible ideas. Take an item and ask a series of what-if questions to expand on what you find. If an item itself has information you might want later, snip it and toss it in a box.

James A. Michener began “writing” a book four or five years in advance. When he “felt something coming on,” he would start reading, as many as 150 to 200 books on a subject. He browsed, read, and checked things. He kept it all in his head and then, finally, he began to write. All that material gave him plenty of ideas to draw upon.

Today, the Internet makes research easier than ever. But don’t ignore the classic routes. Books are still here, and you can always find people with specialized knowledge to interview. And if the pocketbook permits, travel to a location and drink it in. Rich veins of material abound.

Don’t forget experts, either. Find and interview people who lead in their fields. Go to ordinary folks who lived through certain periods or in certain places to get rich detail and factual accuracy.

Here’s a quick way to get ideas from research:

Do this, and soon your heart will connect with some bit of data that fires you up.

Try this exercise first thing in the morning. Your subconscious has been dreamily percolating through the night. It has things to tell you. So grab your cup of Joe and get to a paper or computer screen. Start with, “What I really want to write about is …”

Then write for ten minutes without stopping. Follow the thoughts that come to you, expanding them, going on to others, floating on the streams of your consciousness.

This is not only good for ideas, but also to loosen up your writing muscles. You can use this as a warm-up to your writing day.

By its nature, an obsession controls the deepest emotions of a character. It pushes the character and prompts her to action. As such, it is a great springboard for ideas.

What sorts of things obsess people? Ego? Looks? Lust? Careers? Enemies? Success?

What is Javert’s obsession in Les Miserables? Duty. It drives him to fanaticism and finally death.

What is Ahab’s obsession? A big, white whale. Without that obsession, we’d have no Moby Dick.

Dorian Gray is obsessed with youth.

All of the characters in The Maltese Falcon are obsessed with the black bird.

In Gone With the Wind, Rhett is obsessed with Scarlett. Scarlett is obsessed with Ashley. Therein lies the tale.

Create a character. Give her an obsession. Watch where she runs.

Dean Koontz wrote The Voice of the Night based on an opening line he wrote while just “playing around”: “You ever killed anything?” Roy asked.

Only after the line was written did Koontz decide Roy would be a boy of fourteen. He then went on to write two pages of dialogue that opened the book. But it all started with one line that reached out and grabbed him by the throat.

Joseph Heller was famous for using first lines to suggest novels. In desperation one day, needing to start a novel but having no ideas, these opening lines came to Heller: “In the office in which I work, there are four people of whom I am afraid. Each of these four people is afraid of five people.”

These two lines immediately suggested what Heller calls “a whole explosion of possibilities and choices.” The result was his novel Something Happened.

Likewise, Heller’s classic Catch-22 got started when he wrote these lines:“It was love at first sight. The first time he saw the chaplain, Someone fell madly in love with him.” Only later did Heller replace Someone with the character’s name, Yossarian, and decide that the chaplain was an army chaplain, as opposed to a prison chaplain. The lines conceived the story.

Writing opening lines is fun. Try it. Your imagination will thank you.

Page-turning fiction today often begins with an action prologue. It doesn’t have to involve the main character either. But something exciting, mysterious, suspenseful, or shocking happens that makes the reader say,“Hey, I better read the rest of the book to find out why this happened.”

Gripping openings are fairly easy to write. The trick is putting a book after it. But the ideas you generate with a good prologue may lead to a full story. And writing a prologue of 1,000 to 2,000 words every now and then is great practice for writing page-turning fiction.

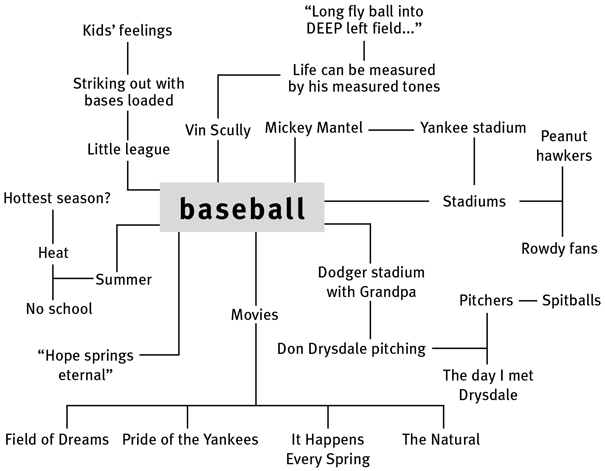

The venerable practice of mind mapping is always a promising method of creation. A mind map is simply a web of quick associations, rendered in visual form. The process can be broken down into three phases:

[1] Ready. Choose a word or concept to develop. It may be one you have in mind already, or it can be chosen at random. Write the word in the center of a blank sheet of paper and draw a circle around it.

[2] Fire.

Without much thought, allow your mind to jot down connections and associations. Don’t worry about making sense of it at this stage. Just go. Allow your associations to spawn other associations. Fill up the paper.

[3] Aim. Soon, your pattern-mind will give you what Gabriele Lusser Rico calls a “trial-web shift.” This is a new “sense of direction” that comes to you out of the associations you’ve made. (See Rico’s Writing the Natural Way, chapter five. This is a superb book on mind mapping for writers.) This shift will provide you with a new sense of direction or focus in terms of your map. You will discern the message that your exploding mind wants to send you. You will have an idea.

For example, my word is baseball. Here I go:

As I pondered this web, it occurred to me that my youth, and the hopes that resided therein, are central. My memories of Dodger Stadium and Little League and Vin Scully on hot summer nights are a rich vein from which I can come up with dozens of possible story ideas.

I think I will.

What is it that makes Casablanca more than just a good film? What gives it a lasting resonance that leaves you with a satisfied “Ah”? I believe it is the ending, with that great final line: “Louis, I think this is the start of a beautiful friendship.”

A socko ending.

Endings often make or break a story. If the ending is flat, we are unsatisfied, even if what has come before is compelling. Frank Capra said this is what happened with his film, Meet John Doe. The story setup was wonderful, but when they got to the ending, Capra and the writers didn’t know what to do. The most logical outcome would have been for John Doe to jump from the building and kill himself. But that would have made the film depressing. The choice they finally made, having the common folk rush up to save him, didn’t quite ring true. The filmmakers had painted themselves into a corner.

Since endings are so crucial, why not come up with a socko ending first? Try this:

[1] Visualize a climactic scene in the theater of your mind.

[2] Hear music to go with it.

[3] Let the full range of emotions burst forth.

[4] Add characters as you will to heighten conflict.

[5] Play around with variations on this theme until something unforgettable happens.

Then ask:

[6] Who are the characters?

[7] What circumstances brought them here?

[8] How can I trace back the story to its logical starting point?

Many writers feel that having a possible ending in mind is the best available narrative compass. At the very least, this socko ending exercise will give you some strong characters.

Much of our self-image is tied up with our work — what we do and how well we do it. There is also a culture associated with individual occupations. So there is plenty of material inherent in the kind of work people do.

Try coming up with story ideas based on intriguing work. It will serve you well to keep a list of interesting occupations you come across as you read books, newspapers, and magazines.

One reference I treasure is Dictionary of Occupational Titles, published by the U.S. Department of Labor. This huge, two-volume compendium describes thousands of occupations in detail. Here is a sample listing:

378.363-010 Armor Reconnaissance Specialist (military serv.)

Drives military wheeled or tracked vehicle and observes area to gather information concerning terrain features, enemy strength, and location, serving as member of ground armored reconnaissance unit: Reports information to commander, using secure voice communication procedure. Writes field messages to report combat reconnaissance information. Drives armored, tracked, and wheeled vehicles in support of tactical operations to harass, delay, and destroy enemy troops. Directs gunfire from vehicle to provide covering or flanking fire against enemy attack. Prepares and employs night firing aids to assist in delivering accurate fire. Tests surrounding air to determine presence and identity of chemical agents, using chemical agent detecting equipment, radiac, or radiological monitoring device. Drives vehicle to bridle locations to mark routes and control traffic. Requests and adjusts mortar and artillery fire on targets and reports effectiveness of fire.

The above might suggest a number of stories. What if this character got lost? Drove through a time warp into 1850? Went crazy? What areas of further research are suggested?

Maybe you’re sitting before a blank sheet or screen and there is nothing in your head. Zero. You’ve exhausted all your possibilities. You are a desperate writer.

Good. Many other great writers have shared your misfortune. And they have found a way out. The answer is just write anyway.

Before writing Ragtime, E. L. Doctorow was desperate. He explains, “I was so desperate to write something, I was facing the wall of my study in my house in New Rochelle and so I started to write about the wall. That’s the kind of day we sometimes have, as writers. Then I wrote about the house that was attached to the wall. It was built in 1906, you see, so I thought about the era and what Broadview Avenue looked like then: trolley cars ran along the avenue down at the bottom of the hill; people wore white clothes in the summer to stay cool. Teddy Roosevelt was President. One thing led to another and that’s the way that book began, through desperation to those few images.”

Maupassant used to advise, “Get black on white.” James Thurber said, “Don’t get it right, just get it written.”

Are you desperate?

Get black on white. Now!

Okay, you’ve got a bunch of ideas there. (You don’t? Get busy!) Now what? Choose your favorite idea and write a hook, line, and sinker.

The hook is the big idea, the reason a reader browsing in the bookstore would look at your cover copy and go, “Wow!” The big idea in Midnight by Dean Koontz is the abuse of biotechnology, which affects an entire town. What’s the big idea behind your book?

Now comes the line. Write the grabber copy for your idea in one or two sentences. Another of Koontz’s novels, Winter Moon, was summed up this way: “In Los Angeles, a city street turns into a fiery apocalypse. In a lonely corner of Montana, a mysterious presence invades a forest. As these events converge and careen out of control, neither the living nor the dead are safe.”

Finally, think hard about a sinker. This is the negative angle, what might possibly sink your idea as a venture. That doesn’t mean you get rid of the idea (though you may); you can also strengthen it considerably. Here are the questions you need to ask and answer to your satisfaction before moving on:

[1] Has this type of story been done before? (Almost always, the answer will be yes.) If it has, what elements can you add that are unique? Brainstorm a list of possibilities. Keep on brainstorming until you have something no one has seen before.

[2] Is the setting ordinary? If so, where else might you set the story? What sort of background has not been done to death?

[3] Are the characters you’re thinking of made of old stock? If so, how can you make them more interesting? What fresh perspective can you provide? Again, do some free-range brainstorming and don’t throw out any ideas until you have generated a long list.

[4] Is this story “big enough” to grab a substantial number of readers? If not, what can you do to make it bigger? How might you raise the stakes? Almost always, death (physical or psychological) must be a very real possibility.

[5] Is there some other element you can add that is fascinating? Think of the idea from every angle, and how you might add a twist or two that enlivens the whole. Yes, it’s more list making. Just do it.

Like cookies and love, story ideas need to be fresh to be truly satisfying. By applying these questions to your story idea, you’ll keep yourself from starting down a long path that may turn toward dullsville.

What editors and agents will tell you is that they are looking for a “fresh, original voice” within the cosmos of what has worked before. In other words, they want it both ways: original, yet not so original that the people in the marketing department won’t know what to do with it.

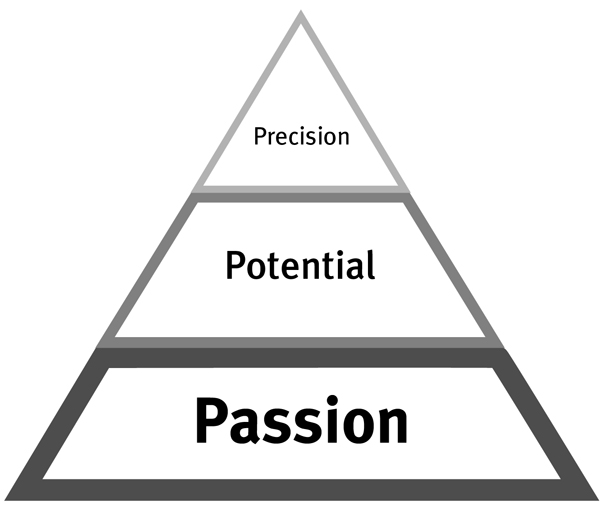

So give them both. Give one final pass on your best ideas by putting them into Bell’s Pyramid. (Forgive me, but never having had a pyramid bear my name, I went ahead and named this one.)

The base of the pyramid is plot passion. You are going to be spending a lot of time with the plots you choose to write. A novel can take months, sometimes years. So you’d better have a passionate desire to take the plunge in order to sustain yourself in the long haul.

Why are so many novels rejected? One reason is they seem “cookie cutter.” They follow the crowd because the writer often thinks, “Gee, if I write something like something else that is successful, I can get published.”

This is a major mistake. Without a passionate commitment to the plot as a story you’re burning to tell, your voice will not be original or compelling. You will just end up sounding like the maddening crowd of other wannabes pounding on the doors of opportunity.

Of all the strata of the pyramid, passion is the most important for your writer’s soul and, almost always, your ultimate success. While it is fine to do journeyman work for money (if you are learning the craft), I believe we writers must nourish and nurture our individuality. Only then do we rise above the commonplace.

As Brenda Ueland says, “Work with all your intelligence and love. Work freely and rollickingly as though they were talking to a friend who loves you. Mentally (at least three or four times a day) thumb your nose at all the know-it-alls, jeerers, critics, doubters.”

You may even, if you wish, thumb your nose at me. Just make sure you’re passionate about doing so.

On the next level, you consider the possible reach of the idea to an audience. For a moment, take off your artist’s hat and assume the role of a potential investor. If you were going to put up many dollars to publish this book, do you have a chance to recoup the investment and make a little profit besides?

Be ruthless in your evaluation. Does an eight-hundred-page fictional rendition of a few years of your life hold much interest for a circle wider than your immediate family? It may, but tell your investor-self why.

Are you entranced by the romance of fish gutting? Explain this to your investor-self.

And do a little market research. You ought to subscribe to Publishers Weekly and keep up with the business. What is being published? Each issue of Publishers Weekly lists “Forecasts,” short reviews of upcoming books. Ask yourself what the publisher sees in these plots.

Don’t copy. Just be aware that much of the potential of a published work is in the author’s original voice and vision.

Note, too, that your assessment of potential need not be with the largest possible audience in mind. Genre writers know they are limiting themselves to a distinct group of potential readers. Even within genres, there are subgroups. Many science fiction writers, for example, are not writing “hard” science fiction, but rather books about deeply held philosophical ideas. They know that such novels appeal to some sci-fi readers and not to others. That’s fine. They are motivated by passion, which we’ve already discussed.

Looking at potential, then, is just a tool to help you make a decision. It is not a “rule.” As with any tool, use it wisely.

Finally, be precise in your plot goals. If you are passionate about your idea and reasonably certain about the potential it has to reach readers, trim away anything that is not in line with that potential. If the plot is going to be for a suspense audience, aim it there. Don’t anticipate using anything else that will distract from that goal.

I have used Dean Koontz’s 1989 thriller, Midnight, in my suspense writing class because it was a runaway bestseller (Koontz’s first No. 1 hardcover on the New York Times list), and it uses many of the techniques discussed. I’ll tell you what you need to know about the novel, but if you want the full benefit I suggest you get yourself a copy and read it through at some point.

Since this chapter is about getting ideas, you might ask yourself how Koontz got the idea for Midnight. We can only speculate, but here are some distinct possibilities. More than one may have played a part:

So you see, there are any number of ways a master storyteller like Dean Koontz may have come up with the initial idea for his first New York Times No. 1 hardcover bestseller. What’s stopping you from doing the same?

This week, choose two ways to get ideas. Set aside at least one hour of writing time for each exercise. Do them.

Pick the idea you like the best from the previous exercise, and give this idea a hook, line, and sinker.

Now, apply Bell’s Pyramid to your idea. Is there enough passion, potential, and precision to make you want to continue?

Even if you decide not to dedicate a whole novel to this idea, going through the process will help you the next time. But if you like the idea, use the rest of this book to get it into fighting shape.

Resolve to set aside a few hours a month just for getting ideas. Stay alert to the idea possibilities all around you. Jot down notes. Rip out newspaper items. Once a month, go through your ideas and nurture them.