We are all experts on human facial expressions. Research shows that even infants can detect changes in facial expressions. The tiniest change can signal an altered mood, and each of us seems to have a memorized catalog of expressions that helps us interpret the faces we encounter. During face-to-face conversations, both persons are aware of the other’s whole face, and both are, of course, attending to the words spoken and hearing the tone of voice, but the main visual focus is on eye-to-eye contact, with the other facial features (eyebrows, forehead creases and wrinkles, mouth, etc.) playing a supporting role. Such an encounter may seem like an ordinary, everyday event, but in fact it is visually complicated.

One of the complications is that we generally think of human faces as symmetrical. We have two eyes arranged on either side of a center line that divides the eyebrows, the nose, and the mouth into a seemingly same-sided whole face. But when photographers divide a photo of a face and rearrange each of the face halves into two whole faces, we can see the slight but definite differences between one half of a face compared to the other half. As I have stated, scientists have determined that 65 percent of humans are right-eye dominant, 34 percent are left-eye dominant, and for 1 percent, neither eye (or both eyes) are dominant.

These mirrored face images show us what we would see if, in real-life conversations, it would be possible to focus on just one side of a person’s face and then on the other side and compare the two sides, one against the other. We don’t do that; first, because it is difficult, and second, because we have little or no motivation to compare the two sides, other than a subconscious motivation to find and connect with the person’s dominant eye.

Photos: Martin Schoeller / AUGUST

SEEKING THE DOMINANT EYE

We have often heard someone say, “He (or she) looked me straight in the eye and said . . .” This seems to be what we actually want when we are talking with someone face-to-face—to be looked straight in the eye. But which eye? Subconsciously, for the 65 percent of us who are right-eye dominant, we want that person to visually connect to our dominant eye, the one that is more closely connected to the left-brain hemisphere, the brain half that can supply the right words to convey our ideas and contribute to the verbal content of the conversation. And for the 34 percent of us who are left-eye dominant, the same holds true. We hope that our conversation partner will connect with our left eye.

Whether we are left- or right-eyed, our conversation partner may or may not be aware of our other eye, the “subdominant” eye, more strongly connected to the nonverbal right hemisphere. The subdominant eye may be watching for expressive clues, intuiting the overall meaning of the encounter, attending to the other’s visual body-language signals, facial expression, and tone of voice, but less able to relate to the spoken words—a sort of silent participant in the conversation.

One of the purposes of this book is to throw some light onto this somewhat unknown aspect of ordinary person-to-person encounters: the importance of looking someone “straight in the eye”—specifically, in the dominant eye. Determining which is the dominant eye requires a bit of knowledge of what to look for. That bit of knowledge can help us overcome our visual habit of automatically connecting to the eye of our conversation partner that is the same as our own dominant eye. This habit is illustrated in the next section.

HABITS OF SEEING—OR NOT SEEING

While human faces are enormously significant to us, linking us to friends, family, and all the people who are important to us, over time we all develop certain habits of seeing—or not seeing—the faces we encounter.

One of the habits (particularly for the 65 percent of us who are right-eyed) is to simply engage automatically right eye to right eye. This habit is cleverly illustrated by author Terry Landau in the 1989 book About Faces.

Without willing it, right-handed, right-eyed people (the 65 percent of humans) focus automatically and strongly on the left side (right eye of both drawings, below). They therefore see the top face as sad, troubled, or angry, and see the bottom face as happy, cheerful, and friendly. Even when you know that it is the same drawing, just reversed, it is very difficult to change that first impression, illustrating how strongly the right-eye-to-right-eye focus affects our response to a face.

“Illustrations” from About Faces by Terry Landau, copyright © 1989 by Terry Landau. Used by permission of Anchor Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

If, of course, you are one of the 34 percent of humans who are left-eye dominant, the reverse is likely to be true. You will see the top face as cheerful, friendly, and happy, and the bottom face as sad, troubled, or angry.

If you are part of the 1 percent who have equal-eye dominance, the conjecture is that you will see neither eye as dominant and/or both faces as “interesting” or “hard to read.”

There are consequences to this automatic tendency for eye contact. For the 65 percent of us who are right-eye dominant, eye contact is automatically dominant eye to dominant eye—right eye to right eye. The other eye, the “subdominant eye,” is largely ignored, aware of the verbal conversation but not attending to the spoken words. Nevertheless, the other person’s subdominant eye is there, watching for emotional clues, intuiting the overall feeling of the encounter, attending to facial expression (especially eye expression) and tone of voice.

If the nonverbal clues match the spoken words, or at least fit well enough with the spoken words, all goes well. If not, our conversation partner might later report, “Well, the words sounded okay, but there was something about the conversation that made me uncomfortable.”

A consequence of our subconscious desire to connect dominant eye to dominant eye is that the 34 percent of us who are left-eye dominant must find ways to persuade a right-eyed person to change the automatic right-eye-to-right-eye response to a right-eye-to-left-eye focus. The 34 percent, therefore, may undertake a set of curious actions to guide our right-eyed conversation partners to our dominant eye. The simplest is just turning the head slightly, so that the dominant eye is forward. Another is lowering the eyebrow over the subdominant left eye, and raising the eyebrow over the dominant eye, as in this photograph of artist Chuck Close, whose right eye is clearly dominant.

It would be hard to mistake which of artist Chuck Close's eyes is his dominant eye.

A more telling ploy is to hold one hand up to the face, partially covering the subdominant eye and forcing attention to the dominant eye.

Dorothy Parker (1873–1967), legendary New York literary figure, journalist, and poet. She was known for her biting wit. Among her famous quotes: “Men seldom make passes at girls who wear glasses” and “The first thing I do in the morning is brush my teeth and sharpen my tongue.” In the late 1910s, Parker worked for Vogue and Vanity Fair, then later as a book reviewer for the New Yorker magazine.

Photo by Vandamm Studio © Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

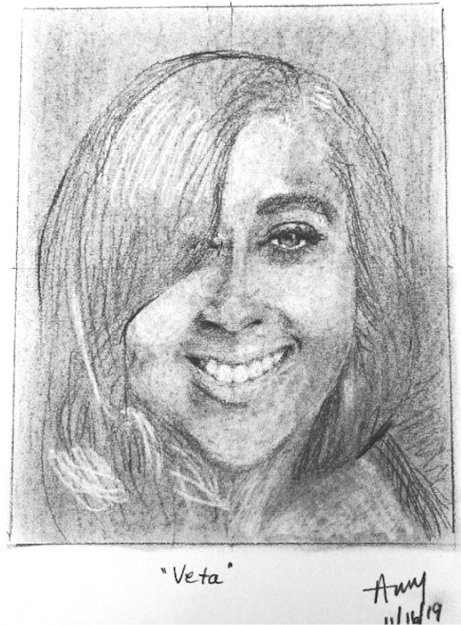

A portrait of Veta by Amy Scowen Walsh, a Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain workshop student, was created in November 2019.

Veronica Lake (1922–1973), a movie actress best known for her work in the 1940s, famously popularized this hairdo, which fully covered her right eye.

Yet another ploy is to use eyeglasses, fortuitously very slightly angled lower over the subdominant eye to mask it and force the desired attention to the dominant eye.

Most drastic of all is a hairstyle that has come and gone over the past nearly hundred years and occasionally shows up today among female TV anchors and others. The hair is styled to literally cover the subdominant eye so that it is hidden from view—a nonsubtle way to force viewers to attend only to the dominant eye.

THE EYES AND “HUMAN SOCIAL SIGNALING”

The split-second assessment of Terry Landau’s drawings (this page) involved only two of literally hundreds, if not thousands, of possible facial expressions that we are decoding on a routine basis every day of our lives. Scientific research in this field (called “human social signaling”) tells us that the eyes alone can convey countless variations of human facial expression. To simplify their investigations, researchers in 2017 narrowed their field of study to just six basic categories of eye expressions: joy, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, and anger.

In their report, the researchers noted that they were “surprised”* to find that all six of the basic eye-expression categories were largely expressed in only two ways: by either widening or narrowing the eyes. The researchers reported that the same two main expressions were originally described by the nineteenth-century evolutionist Charles Darwin in his iconic book On the Origin of Species, published in 1859. Darwin specified the two eye expressions as functional aids to human survival in prehistoric time: widened eyes (letting in more light and expanding the visual field) to enable seeing any large, lurking dangers such as dinosaurs or tigers; or narrowed eyes (reducing the field of vision) to better discriminate small hidden threats—snakes and spiders.

President Donald Trump’s official White House portrait, courtesy of WhiteHouse.gov

Representative Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) at a press conference in the US Capitol on Wednesday, March 22, 2017

According to today’s scientists, these two “all-purpose” eye expressions have now become the major and most frequent social signaling ploys: narrowed eyes expressing discrimination, suspicion, disgust, disapproval, puzzlement, and disdain; and widened eyes expressing surprise, sudden pleasure, shock, fear, anger, and joy. Unexpectedly, two major figures in today’s politics epitomize these two main expression categories.

ARTISTS AND THE ART OF PORTRAYING HUMAN FACIAL EXPRESSIONS

Over the centuries, artists have been obsessed with human facial expressions and how to portray them. The success or failure of a work of art that includes human beings can often depend on that one aspect of a painting, drawing, or sculpture.

As everyone who has ever tried it knows, accurately portraying any of the countless human emotions by means of facial expression is incredibly, frustratingly difficult. With the slightest slip of the brush or pen or etching tool, a pleasant smile becomes a sarcastic grin. Anger becomes disgust. Tender regard becomes sadness or despair. And starting over is sometimes the only remedy. The Italian Renaissance artist Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) wrote in his 1450 instructions for artists, On Painting, “Who would ever believe who has not tried it how difficult it is to attempt to paint a laughing face, only to have it elude you so you make it more weeping than happy?”

Today, artists have photography and freeze-frame images to help them re-create subtle, fleeting human expressions in works of art, but even now, the portrayal difficulties are still there. During the centuries before photography, artists had to rely solely on serious study, close observation, and technical skill. One of the artists best known for success in this endeavor is the Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669).

REMBRANDT AND SELF-PORTRAITURE

From his earliest years as an artist, Rembrandt was interested in self-portraiture, and he was among the first artists to concentrate on facial expression by using his own face to study the subject. In his midtwenties, Rembrandt embarked on a small series of self-portrait etchings that depicted his own face expressing widely different emotions. One can imagine the artist trying out expressions in a mirror, contorting his face to show surprise or shock, laughter, anger, puzzlement, or fear. The etchings that resulted were clearly exercises in portraying a variety of expressions and formed the start of Rembrandt’s lifelong passion for self-portraiture and the portrayal of human emotions.

In Rembrandt’s time, long before photography, artists had only mirrors as aids in self-portraiture. It is hard to imagine the difficulties Rembrandt faced in creating his series of self-portraits expressing emotions in one of the most challenging of all mediums, etching on a copper plate.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), Self-Portrait (1660). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913.

This complicated process begins with a thin copper plate covered with a thin coat of dark resin. The artist uses a pointed metal tool to scrape the lines of a drawing through the dried resin coating to reveal the copper beneath. When the drawing is complete, the artist applies acid to the plate, which etches (eats away) the copper exposed by the lines scratched through the resin. The acid forms grooves in the copper that will hold ink during printing. The remaining resin is then removed, and the plate is cleaned. Next, the artist dabs ink on the copper plate and wipes it to remove all the ink except for the ink embedded in the scratched-out, acid-enlarged grooves. The artist then covers the plate with a damp sheet of paper and runs it through a printing press to pick up the inked scratch marks of the drawing. Finally, the finished paper print with the inked image is pulled off the plate and hung on a line to dry. (See the illustration below of the etching process.)

The potential pitfalls in this long and daunting process are profuse: etched lines may not be deep enough or may be too deep; the acid may be too strong and ruin the copper plate; too much ink is applied or too little ink; the ink may be too thick or too thin; the paper may be too wet or too dry—the potential problems are endless, and the artist can’t know what issues might arise until the whole process is completed and errors show up in the printed image. Even then, the problems are not over. The printed image is a mirror image (a reversed image of the original drawing on the copper plate), inevitably magnifying any problems with the original drawing. Even signing the drawing on the copper plate is a problem. If the artist, without thinking, signs the plate with his normal signature, the signature will be reversed on the print, as happened a few times with Rembrandt’s etchings.

Abraham Bosse (1602/1604–1676) The Intaglio Printers (1642). The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

To all these technical problems, add that Rembrandt was using his own face as his model and therefore had to repeatedly pose in a mirror with the desired facial expression (for example, eyes widened, head pulled back, mouth pursed), study it, remember it, then turn to the resin-covered copper plate and reproduce that particular part of the expression using the pointed etching tool. Then, after turning again to the mirror, manipulating his face again into the desired expression, studying the image and memorizing it, he again goes back to work on the plate. And the process goes on and on. Rembrandt sometimes worked for several years on a single copper plate until he was satisfied with the prints (having cannily sold the various versions in the process).

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait in a Cap, Wide-eyed and Open-mouthed (1630). Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Long Bushy Hair: Head Only (c. 1631). Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

As a result, we have this marvelous small set of etchings portraying human facial expressions by one of history’s greatest artists. And among them are definitive images of the two major eye expressions singled out as broadly useful by many present-day researchers in the field of social signaling: widened eyes and narrowed eyes.

Self-Portrait in a Cap, Wide-eyed and Open-mouthed, dated 1630, is from Rembrandt’s early self-portrait etchings, in which he used his own face to portray various facial expressions. According to our current scientists, the widened eyes in this etching could be expressing a huge range of emotions, from wonder or surprise to sudden fear, pleasure, anger, joy, incredulity, shock, or alarm. It is mind-boggling to learn that the copper plate on which Rembrandt etched this powerful image measures only 2" by 1½" (50 mm by 45 mm).

A second etching from the early series, titled Self-Portrait with Long Bushy Hair, is from about the same period (1631). It portrays the second of modern scientists’ theory of two major eye expressions: narrowed eyes expressing disapproval, suspicion, puzzlement, or disdain, disappointment, despair, or countless other negative emotions. This etching is also tiny, about 3" by 2½" (64 mm by 60 mm).

It appears from these etched images that Rembrandt was right-eye dominant. The right eye is more open, looking directly at the viewer. The left eyebrow is pulled forward, and the crease above the left eyebrow almost forms an arrow pointing to the dominant right eye. The image on the copper plate, drawn from a mirror image, would reverse Rembrandt’s face, but the consequent paper print would re-reverse the image, indicating right-eye dominance, which later self-portraits appear to verify (see this page).

Following Rembrandt’s lead, artists across the centuries and around the world have recorded the effects of emotion on the human face, largely conveyed by the eyes. To this day, artists and photographers are inspired by the power of human faces to express emotions, especially the expressions of the eyes, the “windows of the soul.”

Portrait of Salvador Dalí, taken in Hôtel Meurice, Paris, 1972

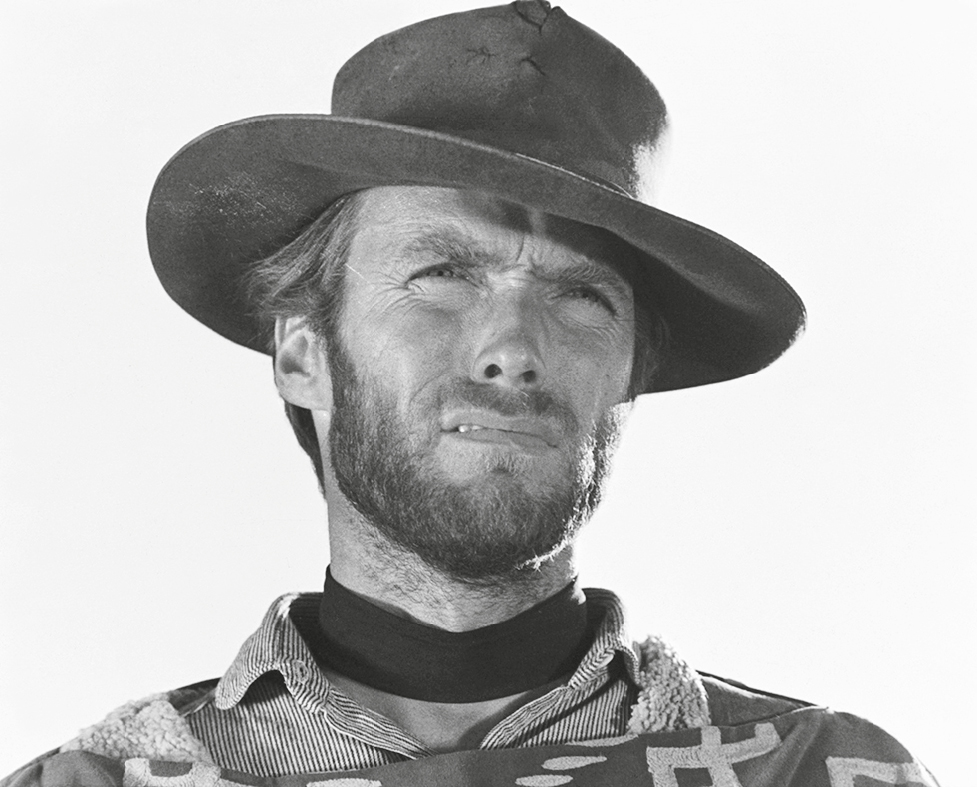

Clint Eastwood, from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966