Definitions of Fascism

Few words cause more confusion and heated debate than fascism. It is often used in the sense of extreme repression. Often the understanding of fascism is limited to the Nazis dictatorship. The term has been applied to many individuals, such as Joseph McCarthy, J. Edgar Hoover and others. It is frequently - often wrongly - used to describe police and law enforcement, and government and its policies.

What then is fascism exactly? Webster’s Dictionary defines it as: “A government system marked by a centralized dictatorship, stringent socioeconomic controls and belligerent nationalism.”

Benito Mussolini, the world’s first fascist dictator, said: “Fascism should rightly be called Corporatism, as it is a merge of state and corporate power.” The word fascism stems from the Italian word fascio, a union or league, and the Latin word fasces, an ancient Roman symbol of authority consisting of an executioner’s ax bound in a bundle of rods. Under ancient Roman law, it originally symbolized the power to kill mercifully with the ax or mercilessly by beating the condemned to death with the rods. It is also interpreted as “Strength Through Unity,” the fascist motto in V for Vendetta; in other words, corporatism. The reverse side of the Mercury dime depicts a fasces.

Upton Sinclair defined fascism simply as “capitalism plus murder.” According to Franklin Roosevelt:

The liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself. That, in its essence, is fascism - ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or any controlling private power.

Another good definition of fascism comes from Heywood Broun, a noted American columnist in the 1930s:

Fascism is a dictatorship from the extreme right, or to put it a little more closely into our local idiom, a government which is run by a small group of large industrialists and financial lords... I think it is not unfair to say that any businessman in America, or public leader, who goes out to break unions is laying the foundations for fascism.

A lengthy description of fascism often credited to Mussolini is in the 1932 Italian Encyclopedia edited by Giovanni Gentile. Excerpts from that description are given in Appendix 1.

Overall, these definitions are vague and abstract. Roosevelt’s definition comes closest to the true essence, but even his is incapable of taking into account all forms of fascism. Like democracy, fascism comes in many forms. Further, no fascist state has ever first appeared full-blown. Even the Nazis and Mussolini took several years to consolidate their power. It’s that gradual transition that makes fascism so insidious.

The lack of a clear definition of fascism led the War Department to develop a training program to teach new inductees what they were fighting. The War Department released Program 64 on March 24, 1945. An excerpt from that program alludes to the difficulty in precisely defining a fascist.

Three Ways to Spot U.S. Fascists.

Fascists in America may differ slightly from fascists in other countries, but there are a number of attitudes and practices that they have in common. Following are three. Every person who has one of them is not necessarily a fascist. But he is in a mental state that lends itself to the acceptance of fascist aims.

1. Pitting religion, racial, and economic groups against one another in order to break down the national unity is a device of the divide and conquer technique used by Hitler to gain power in Germany and in other countries. With slight variations, to suit local conditions, fascists everywhere have used this Hitler method. In many countries, anti-Semitism (usually more accurately termed Judeophobia, as the word “Semitic” denotes mainly the language of the Arabs, and not the religion of the Jews) is a dominant device of fascism. In the United States native fascists have often been anti-Catholic, anti-Jew, anti-Negro, anti-Labor and anti-foreign born. In South America native fascists use the same scapegoats except that they substitute anti-Protestantism for anti-Catholicism. Interwoven with the master race theory of fascism is a well-planned hate campaign against minority races, religions, and other groups. To suit their particular needs and aims, fascists will use any one or a combination of such groups as a convenient scapegoat.

2. Fascism cannot tolerate such religious and ethical concepts as the brotherhood of man. Fascists deny the need for international cooperation. These ideas contradict the fascist theory of the master race. International cooperation, as expressed in the Dumbarton Oaks proposals, run counter to the fascist program of war and world domination. Right now our native fascists are spreading anti-British, anti-Soviet, anti-French and anti-United Nations propaganda.

3. It is accurate to call a member of a communist party a communist. For short, he is often called a Red. Indiscriminate pinning of the label Red on people and proposals which one opposes is a common political device. It is a favorite trick of native as well as foreign fascists.

Many fascists make the spurious claim that the world has but two choices - either fascism or communism - and they label as communist everyone who refuses to support them. By attacking our free enterprise, capitalist democracy, and by denying the effectiveness of our way of life, they hope to trap many people.

Program 64 set off a major firestorm of criticism in Congress. Led by pro-fascist members, the controversy raged until the War Department gave up the program.

Characteristics of Fascism

This book defines fascism as follows, with one condition. Fascism is a repressive totalitarian regime in which a small elite controls and uses the government for their benefit. Any action by a government that places the rights of a corporation or a group of elites above the rights of the people is a step toward fascism. However, even this definition fails to delineate the transformation from a capitalist democracy to a fascist state. For instance, when did Germany become a fascist state? Did it occur with Hitler’s appointment as chancellor? Or was it before or after the appointment?

While the March 1933 election was not free, nevertheless, the Nazi Party failed to gain a majority in the Reichstag. Thus it can be argued that the transformation occurred after that election. However, Germany was well along the road to a full fascist state before Hitler’s appointment.

The lack of a clear line marking the transformation to a fascist state points again to the movement’s insidious nature, and the impossibility of relying on simplistic definitions. Since there is no all-encompassing definition, it is best to look at the traits that explore the degree of fascism. While many of the traits of fascism are almost universally included on such lists, some are hotly contested. Political scientist Lawrence Britt listed the following:

1. Powerful and Continuing Nationalism: Fascist regimes tend to make constant use of patriotic mottos, slogans, symbols, songs and other paraphernalia. Flags are seen everywhere, as are flag symbols on clothing and in public displays.

2. Disdain for the Recognition of Human Rights: Because of fear of enemies and the need for security, the people in fascist regimes are persuaded that human rights can be ignored in certain cases because of “need.” The people tend to look the other way or even approve of torture, summary executions, assassinations, long incarcerations of prisoners, etc.

3. Identification of Enemies/Scapegoats as a Unifying Cause: The people are rallied into a unifying patriotic frenzy over the need to eliminate a perceived common threat or foe: racial, ethnic or religious minorities; liberals; communists; socialists, terrorists, etc.

4. Supremacy of the Military: Even when there are widespread domestic problems, the military is given a disproportionate amount of government funding, and the domestic agenda is neglected. Soldiers and military service are glamorized.

5. Rampant Sexism: The governments of fascist nations tend to be almost exclusively male dominated. Under fascist regimes, traditional gender roles are made more rigid. Opposition to abortion is high, as is homophobia and anti-gay legislation and national policy.

6. Controlled Mass Media: Sometimes media are directly controlled by the government, but in other cases, the media are indirectly controlled by government regulation, or sympathetic media spokespeople and executives. Censorship, especially in wartime, is very common.

7. Obsession with National Security: Fear is used as a motivational tool by the government over the masses.

8. Religion and Government are Intertwined: Governments in fascist nations tend to use the most common religion in the nation as a tool to manipulate public opinion. Government leaders frequently use religious rhetoric, even when the major tenets of the religion are diametrically opposed to the government’s policies or actions.

9. Corporate Power is Protected: The industrial and business aristocracy of a fascist nation often puts government leaders into power, creating a mutually beneficial business-government relationship and power elite.

10. Labor Power is Suppressed: Because the organizing power of labor is the only real threat to a fascist government, labor unions are either eliminated entirely or are severely suppressed.

11. Disdain for Intellectuals and the Arts: Fascist nations tend to promote and tolerate open hostility to higher education and academia. It is not uncommon for professors and other academics to be censored or even arrested. Free expression in the arts is openly attacked, and governments often refuse to fund the arts.

12. Obsession with Crime and Punishment: Under fascist regimes, the police are given almost limitless power to enforce laws. The people are often willing to overlook police abuses and even forego civil liberties in the name of patriotism. There is often a national police force with virtually unlimited power.

13. Rampant Cronyism and Corruption: Fascist regimes are almost always governed by groups of friends and associates who appoint each other to government positions, and then use governmental power and authority to protect their friends from accountability. It is not uncommon in fascist regimes for national resources and even treasures to be appropriated or even outright stolen by government leaders.

14. Fraudulent Elections: Sometimes elections in fascist nations are a complete sham. Other times, elections are manipulated by smear campaigns against or even assassination of opposition candidates, use of legislation to control voting numbers or political district boundaries, and manipulation of the media. Fascist nations also typically use their judiciaries to manipulate or control elections.

Some additional, more definitive traits of fascism, roughly in order of their importance, are:

Top-Down Revolution or Movement: Fascism is a rebellion or revolt by the elite to preserve their social economic status. This is the primary reason fascism begins during periods of economic turmoil. While the large number of followers of fascism such as Hitler’s Brown Shirts came from the middle and lower classes, the elite of German society controlled the party. It was only after Hitler assured the prominent business leaders of his opposition to socialism and unions that he gained power.

Unbridled Corporatism: The corporate leaders direct government policy for their own benefit. Fascism reduces controls on business and suppresses or bans unions.

Extreme Anti-communism, Anti-socialism and Anti-Liberal Views: Fascists regard the state as supreme and the individual as subordinate to the state. Fascism cancels or forces deep cuts in social programs.

Extreme Exploitation: Fascist regimes reduce people to objects of the state without human rights. Citizenship may be revoked from groups of people to exploit them and seize their property. (See also No. 2 on Britt’s list.)

Totalitarian: Fascism does not tolerate dissent. Dissenters face imprisonment or execution. Fascism packs the courts with party ideologues, leaving no recourse for grievances.

Extreme Nationalism: Excessive display of nationalism with flags, mottoes, slogans and other national symbolism is common to all fascist regimes. Fascist governments glorify the military and divert most of the government spending to the military and defense items. Often this extreme nationalism results in the expanding the country’s borders through wars. (Common to both lists.)

Destructive Divisiveness: All politicians in a democracy use divisions to win elections. However, under fascism, the divisiveness is uniquely destructive and often takes the form of racism, class warfare or even genocide. (Similarity with No. 3 on Britt’s list.)

Opportunistic Ideology: Fascists often adopt popular stances on issues to gain and hold power, but once fully in control, they reverse themselves in favor of reactionary positions. Hitler borrowed from socialism to gain power only. Once he gained power, he repudiated these ideas, and socialists were some of the first prisoners in the concentration camps.

Violence and Terror: Fascist regimes use violence and terror to gain and preserve power. Hitler had his Brown Shirts intimidate voters and opposition leaders by starting street brawls and even murdering the opposition. Once in power, he used the Gestapo, the secret state police, to root out and remove any opposition.

Expounding of Mysticism or Religious Beliefs: Hitler often spoke of the declining moral values in Germany, and used the church to manipulate public opinion. The Nazis modeled the SS after both religious and pagan customs. (Common to both lists.)

Cult-like Figurehead: A popular figurehead surrounded by a small cadre of cult-like followers has headed every fascist regime to date.

Censorship: The press and media are tightly controlled under fascism, and reduced to the role of the party’s mouthpiece. (Common to both lists.)

It must be emphasized that not all of these traits need be present in a fascist state. For instance, Nazi Germany was the only fascist state to show extreme racism. There is scant evidence of it in Franco’s Spain, Peron’s Argentina and Pinochet’s Chile. Even in Italy, racism was minor before the Nazis took control.

Strictly speaking, fascist states to are totalitarian and place the rights of corporations above the rights of their citizens. However, there is a wide gray area in defining when a government becomes totalitarian, or at what point protecting corporations becomes fascist.

Understanding this gray area is essential to recognizing how fascist regimes arise. It points to the inherent danger in all societies based on a free market economy. Once an elite class gains enough wealth to control and run the government, it ceases to exist in its own right. Not all free market economies end in fascism; many have ended in right-wing dictatorships. The various coups in Central and South America provide plenty of examples. A few may end in a Marxist revolution, as in Cuba, and others may become democracies. The turn to fascism is the extreme case.

Once again, this gray area makes fascism dangerous and hard to recognize. Unlike communism, fascism does not need a revolution to emerge, although fascist putschists will often use mobs to underpin their coups. Considering the enormous impact the Nazis had on the world, Germany greeted Hitler’s appointment as chancellor with indifference. His appointment followed a long list of short-lived German governments and chancellors. A newsreel shown widely throughout movie theaters in Germany placed Hitler’s appointment last in the six events covered, behind reports on a horse race, a horse show and a ski jump. Similarly, reaction outside Germany was largely indifferent and restrained.

The great indifference to Hitler’s appointment indicates how easy it is for a democracy to slide into fascism. In The End of America, published in July 2007, Naomi Klein outlines ten steps to a fascist takeover:

Invoke an internal and external threat; establish secret prisons; develop a paramilitary force; surveil ordinary citizens; infiltrate citizens’groups; arbitrarily detain and release citizens; target key individuals; restrict the press; cast criticism as ‘espionage’ and dissent as ‘treason;’ and subvert the rule of law.

Klein then gives current, Bushist examples of each. She also notes how many of the steps were followed in the Thai military coup of September 2006, “as if they had a shopping list… Thailand was a police state within a matter of days.” The scenario in the U.S. is more gradual, more banal, but just as overwhelmingly thorough.

Any objective assessment of the George W. Bush administration after the reports of torture at the Iraqi Abu Ghraib prison in May 2004 would find most of the traits from all three lists. Undoubtedly, this government has been one of the most repressive in U.S. history. By spring 2004, some journalists were already describing it as fascist.

The Philosophy of Fascism

Further insights into fascism can be gained by looking at its roots in modern philosophy. March 23, 1919 in Milan, Italy, Mussolini formed the Fasci di Combattiment, fighting leagues or bands. Some writers suggest there was already a well-developed theory of fascism dating back to Karl Marx, but this is part of the futile yet concerted effort by the Right Wing to link fascism with communism and the Left.

Much of their argument stems from the fact that several of the philosophers of fascism, including Mussolini, Sergio Panunzio and George Sorrell, had once been members of the Socialist Party or associated with the Left in other ways. The Socialist Party had expelled Mussolini for his support for the war, and both he and Giovanni Gentile grew to despise socialism. To argue that fascism is a leftist ideology is like claiming that President Reagan was a liberal because he had once been a member of the Democratic Party.

The earliest efforts to define the fascist philosophy came with the printing of the Fascist Doctrine, written by Gentile and often credited to Mussolini. Gentile served as minister of education in Mussolini’s first cabinet, and organized a purge of liberals and democrats in Italian universities. He believed future revolutions would occur in backward countries where people needed to focus their strength on restoring the nation. (This is the opposite of Marx’s theory that revolutions would be a struggle by the working class to gain power in industrialized countries.)

Gentile hated the socialists for their support of continuous strikes and work stoppages in Italy during the chaos immediately following World War I. He sensed the Italian nation was beginning to crumble. Gentile also thought humans have no purpose outside the nation, and all must make sacrifices for it - whereas Marx looked forward to a withering away of the state.

Other themes in the Fascist Doctrine originate with more traditional influences. Corporatism and its theories of class collaboration, and economic and social relations can be traced to the model laid out by Pope Leo XII’s 1892 encyclical Rerum Novarum. There is great similarity between the fascist and encyclical versions of corporatism. The encyclical addressed politics and the way in which the Industrial Revolution transformed society. It sharply criticized socialism and its theory of class struggle, while also citing capitalism for exploiting the masses. Seeking a principle to replace the Marxist doctrine of class struggle, the encyclical urged social solidarity between the upper and lower classes, and approved nationalism as a way of preserving traditional morality, customs and folkways. Pope Leo XII proposed a kind of corporatism, organizing political societies along industrial lines, much like medieval guilds. The pope went so far as to reject the democratic ideal of “one person, one vote” in favor of representation by interest groups.

Italian fascism as a political and economic system combined parts of corporatism, totalitarianism, nationalism and anti-communism. In many regards, it may be considered an ideology of negation: anti-liberal, anti-communist and antidemocratic. It was a reactionary ideology in that it promoted whatever views would be useful to further exploit the people. It was also a reaction against the French Revolution, that landmark event that launched a major shift in European culture and governments, whose motto of “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” the European nobility hated the most.

The concept of liberty from repressive regimes in the daily lives of the citizenry incensed the early philosophers of fascism. Freedom from forced religious values, the right to vote, majority rule in which the minority still held a set of inalienable rights - these were radical ideas in a time of debtor’s prisons, indentured servants and vassal states. Such ideas directly threatened kings, nobles, and the Church.

Equality in the eyes of the law was unspeakable. How could a mere peasant have the same rights under the law as kings, nobles and merchants? There had been a time when the king’s word was the law. The social standing of one’s birth determined one’s rights. The only rights a person had were those the king was willing to extend - and which he could withdraw at any moment. Fraternity, in the sense that all men and women shared humanity, was considered heresy. Society had treated slaves as animals and women as property, not part of a greater humanity. All three terms meant a loss of control by those in power, and the 19th century saw a flourishing counter-revolution of obscurantist philosophy.

Some writers look for signs that 19th century German thinkers like Schopenhauer, Hegel, or Weber foreshadowed Nazism, but with little basis. The 19th century precursor to the fascist ideology was Social Darwinism, an English manufacture, as will be seen in Ch. 3. Germany contributed the mad nihilist Fredrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), known for his Thus Spake Zarathustra and The Will to Power. Hitler liked to be photographed staring at a bust of Nietzsche, the enfant terrible who theorized two sets of morals for the ruling and slave classes. He believed that ancient empires grew out of the ruling class and that religions - which denigrate the rich, the powerful, rationalism and sexuality - arose from the slave classes. “The unhealthy must at all costs be eliminated, lest the whole fall to pieces.” He developed the idea of an Übermensch, or overman, a superhuman, symbolizing man at his most creative and highest intellectual development. “A daring and ruler race is building itself up... to become the ‘lords of the earth.”

... a secret circular went out from the Reich Interior Ministry which marked the beginning of a programme of euthanasia for mentally ill or deformed children up to 3 years old. Doctors would be required to report all such cases to the health authority on special forms; the forms would then be forwarded to a panel of three medical assessors who would adjudicate over life or death by appending “-” or “+.” Should all three place a “+,” a euthanasia warrant would be issued, signed by the Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler of the Fuhrer’s Chancellery or SS Oberfuhrer Dr Viktor Brack, head of the Chancellery’s Euthanasia Department II. And so it happened: infants marked for death were transferred to what were referred to as Children’s Special Departments in politically reliable clinics, there to be given a “mercy death” by injection, or in one institution at Eglfing-Haar simply starved by a progressive reduction of diet.

This superman or perfected man was mirrored in the racialist Nazi concept of “Aryan,” as contrasted to the “Semitic” Jewish minority, as shown in this lurid passage from Hitler’s Mein Kampf:

With satanic joy in his face, the black haired Jewish youth lurks in wait for the unsuspecting girl whom he defiles with his blood, thus stealing her from her people. With every means he tries to destroy the racial foundations of the people he has set out to subjugate. Just as he himself systematically ruins women and girls, he does not shrink back from pulling down the blood barriers for others, even on a large scale. It was and it is Jews who bring Negroes into the Rhineland, always with the same secret thought and clear aim of ruining the hated white race by necessarily resulting bastardization, throwing it down from its culture and political height, and himself rising to be master.

While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has eliminated much of the racial hate in the United States, a good deal remains just below the surface. In late 1998, Sen. Majority Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi and Rep. Bob Barr of Georgia were exposed as members of the Council of Conservative Citizens. The group’s Web site, cofcc.org, still continues to bash blacks in a primitive fashion, and calls itself the No Longer Silent Majority.

The Rise of the Third Reich

Two factors were largely responsible for shaping global policies of the 1920s: the Treaty of Versailles and the rise of Bolshevism. Both figure prominently in Hitler’s rise.

The Versailles Treaty placed severe limits on Germany and demanded harsh reparations. The French delegate Clemenceau demanded even harsher terms than approved by the treaty, hoping to permanently weaken Germany and ensure that France would be the sole continental power. Most historians regard the treaty as the primary cause of the rise of the Nazis, but the Bolshevik Revolution also played a part. It was the bogeyman that most aroused demagogues on the right. Communism, socialism, worker revolutions and unionism threatened the existing social order. In the United States, the Red Scare of 1919 led to extreme anti-unionism. Fascist regimes offered big business owners and rightist leaders protection against communism and worker class movements.

The war was partially responsible for the global rebirth of the hard Right. From their service on the frontlines, many soldiers developed a strict sense of order and harsh justice compatible with right-wing beliefs. J.P. Morgan formed the American Legion to protect business interests and to act as a union-busting group of thugs. The Freikorps in Germany served the same purpose; Hitler himself was a member.

During the 1920s and 1930s fascism came to be viewed as a bulwark against Bolshevism. The Harding, Coolidge and Hoover administrations actively sought to strengthen Mussolini’s hold on Italy to prevent the rise of socialism or communism there.

The end of World War I brought an end to the German Empire and monarchy. A series of weak center-right coalition governments governed the short-lived Weimar Republic (1919-33). Financial problems and internal turmoil rocked the ill-fated republic. The only period of stability was a short span of six years, 1923-29. Fourteen chancellors and 19 cabinets governed before Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. The last year of the republic was especially chaotic with the failure of three governments (Heinrich Brüning, Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher). The rapid changes contributed to the instability and increasing polarization in Germany.

During the 14 years of the Weimar Republic, the government repressed communists and socialists through violence, often assassination. Early on, it used the Freikorps to put down communist uprisings. Gen. Franz Epp, a leader of the Freikorps, led 30,000 soldiers to crush the Bavarian Socialist Republic, killing more than 600 communists and socialists. The Freikorps officially disbanded in 1921, but suppression of the Left continued, often resulting in street battles between the Right and Left.

In 1926, the German army formed an Economic High Command to rearm and prepare for a new war. The Weimar government did nothing to suppress these actions. Instead, it conducted hundreds of treason trials in secret against any worker or journalist who revealed the truth.

Hitler was a member of the List Regiment in Munich. During the attempted socialist takeover of Bavaria, historians believe that Hitler personally executed as many as 10 men. After the uprising was put down, Hitler was promoted in 1919 to a position as a Vertrauens-mann or undercover agent by Capt. Karl Mayr, who was in charge of Section I b/P of army intelligence, a bureau organized to investigate subversive political activities among the troop. Hitler remained an undercover agent until his discharge in late March 1920.

Hitler’s first foray into politics came on Sept. 12, 1919, when his superior officers ordered him to investigate the German Workers’ Party. Hitler attended a mid-September meeting in a little beer hall named Sterneckerbrau to gather information for his report. The fledging party had aroused the attention of the military, which was suspicious of all workers’ groups. Anton Drexler had founded the party on March 7, 1918 under the name “Free Labor Committee for a Good Peace.” The party consisted of roughly 50 railroad men and Drexler friends. After the war, Drexler changed the name, but the same members and chairman remained.

Hitler attended the meeting dressed in civilian clothes. Originally, Dietrich Eckart was slated as the main speaker, but canceled due to illness at the last moment, and Gottfried Feder took his place. Feder was an economic hack, and Hitler was glad when he finished his speech. After an attack on his views, Feder replied with a spirited defense. If the meeting had closed at this point, history might have taken a very different path. However, someone from the audience demanded Bavaria separate from Prussia and unite with Austria. Hitler had pronounced views on German unity and demanded the floor, delivering a rousing speech. It was the first time Hitler spoke before a political party, and the look of astonishment in the eyes of his audience pleased him. Hitler had no high opinion of the members of the tiny party, and had no intention of returning. However, before leaving the meeting, Drexler shoved a pamphlet into Hitler’s hands.

The pamphlet outlined Drexler’s views. While sketching out a “new world order” based on National Socialism, the pamphlet was largely an anti-Jewish tract. A portion follows:

There is a race - or perhaps we should call it a nation - which for over two thousand years has not possessed a state of its own, but has nevertheless spread over the entire earth. They are the Jews. They are not peasants, farmers or factory workers; they do not work in the coalmines or in the building trade. They are the secret “givers of bread” behind every limited liability company; they are the ones who barter everything fashioned by the intellectual and manual skill of mankind. They quickly conquered the money market, although they began in poverty, and were thereby made all the richer in vice, vermin and pestilence. All this they accomplished in the various countries they penetrated, and thus they became the indispensable bankers in all civilized countries and the economic leaders, exerting power over princes and rulers.

Only one per cent of the total population is Jewish but for thousands of years the Jews, from the highest to the lowest, have grimly pursued the thought that this tiny people should never serve rulers but always govern them. Yet they are unable to form a state of their own. Consequently in every country they strive to monopolize the money market, the economy, politics, literature, the press, and this race has almost made themselves the masters of the world.

Hitler recorded his first impression of the party in Mein Kampf as follows:

My impression was neither good nor bad; a new organization like so many others. This was the time in which anyone who was not satisfied with developments and no longer had confidence in the existing parties felt called upon to found a new party. Everywhere these organizations sprang from the ground, only to vanish silently after a time. The founders for the most part had no idea what it means to make a party - let alone a movement - out of a club. And so these organizations nearly always stifle automatically in their absurd philistinism.

Sept. 16, 1919, Hitler received a postcard saying the party accepted his membership and inviting him to attend a special meeting of the executive committee. Although he considered the postcard presumptuous, Hitler decided to go. He soon met Dietrich Eckart, a member of the Thule Society. Behind the front of a literary club studying Nordic culture, the Society was a hard-right political group devoted to anti-Semitism or Judeophobia and aristocratic rule. Its agents had penetrated the government and were adept forgers with powerful ties to the Freikorps.

Eckart began tutoring Hitler by giving him books to read, teaching him to dress properly, introducing him to prominent people, and giving him money - funding that most likely came from other wealthy Eckart acquaintances. The introductions to prominent individuals arranged by Eckart paid large dividends in advancing Hitler and the party.

One of the first such introductions was to Frau Helene Bechstein, wife of the piano manufacturer Carl Bechstein. Hitler intrigued Helene. She soon gave him sizable contributions and began urging her friends to do the same. Her patronage eased the way for Hitler’s acceptance in the highest social circles in Germany.

Hitler recognized that for the party to continue to grow, Karl Harrer, the chairperson and another Thule Society member, had to be replaced. By Feb. 6, 1920 Drexler and Hitler had finished writing the party program, the infamous 25 points (see Appendix 2). Hitler’s speeches had already contributed to the party’s growth.

At this time, the party changed its name to National Socialist German Workers Party. Hitler also insisted on a party flag that could outdo the communist banner. A dentist from Stamberg suggested the design. The swastika has a long history dating back centuries and is found in various cultures, including American Indians. It had long been a symbol of the Teutonic Knights, and was used by the Thule Society and several Freikorp units.

By all accounts, Hitler lived frugally during this time, saving money for the party’s needs and expansion. Since his discharge from the regiment in March 1920, he had no regular source of income. Hitler and the party were compensated from members’ monthly dues and admission charged at meetings and rallies. However, party membership was still fewer than 3,000 by the end of the year. While Hitler was attracting crowds of around 6,000, the party spent much of the income on the welfare of party members, many of who were unemployed.

Before the end of 1920, Hitler insisted on one luxury item, a car, that he believed would dignify the party leadership. A second-hand Selve was purchased from funds raised mysteriously by a party member.

Hitler also wanted a larger forum. He told Eckart that the Völkischer Beobachter newspaper was in financial difficulties and could be bought for 180,000 marks. At 8 a.m., Drexler and Eckart set off to raise the funds. By noon, they had secured 60,000 marks from Gen. von Epp and another 30,000 marks from others. At 4 p.m., the purchase of the paper was properly registered. Hitler named Eckart as the editor of the newly acquired paper.

Shortly after buying the paper, Hitler hired his former sergeant major, Max Amann, as the party’s business manager. Amann was a Thule Society member and could arrange for short-term credit for the party.

In July 1921, Hitler went to Berlin for six weeks to confer with north German right-wing leaders. A former electric company executive and Eckart friend, Dr. Emil Gansser, arranged for Hitler to speak at the prestigious National Club of Berlin. The speech impressed Adm. Ludwig von Schroeder, former commander of the German Marine Corps. The admiral proved to be a great help in winning over the support of the Prussian upper class to the Nazi cause.

While Hitler was in Berlin, a factional revolt directed against him broke out in the party. On his return to Munich, Hitler threatened to resign unless given dictatorial powers over it. The ruse worked and Hitler solidified his position.

In the late summer of 1921, the party’s defense squads of volunteer brawlers reorganized under paramilitary lines. On Oct. 5, 1921 the party officially named them Sturmabteilung or Storm Troopers (SA). It cost a great deal to equip the SA. Shelter and food had to be provided, uniforms, flags and weapons had to be purchased, and there was the cost of transporting them to and from rallies. The money came from the High Command of the Bavarian Army, the Reichswehr. According to author James Pool, the aid was given on the initiative of Capt. Ernst Roehm without the knowledge of his superiors in the Bavarian army, but there is reason to doubt this. Officially in charge of the press and propaganda for the Bavarian Reichswehr, Roehm had much more influence than his rank of captain suggested. Unofficially, the generals took his advice on political matters. He organized many of the Freikorp units and was responsible for hiding arms from the Allied Control Commission. Roehm also was the leader of the SA.

By November 1922, the Nazi Party had moved into larger headquarters and employed 13 full-time staff. A central file system and archive also were developed. Nov. 22, 1922, Ernst (Putzi) Hanfstaengl attended one of Hitler’s speeches on a suggestion from Capt. Truman Smith, the assistant military attaché of the U.S. Embassy. Hanfstaengl was an anti-communist, and his mother, who was from a wealthy American family, owned an art business in Munich. Impressed by Hitler’s speech, he joined the Nazi Party. Soon after, he loaned $1,000 to the party to buy a couple printing presses and convert the new party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter from a weekly to a daily.

By the end of 1922, the German mark fell to 400 against the U.S. dollar. Hyperinflation continued through 1923. During the hyperinflation, Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter was the most important fund-raiser for the Nazi Party. The wealthy Scheubner-Richter approached aristocrats, big business leaders and leaders of heavy industry for contributions. Scheubner-Richter was a close friend of Gen. Erich Ludendorff, who channeled money to him from industrialists. Ludendorff was a prominent World War I general who fled to Sweden claiming left-wing politicians had stabbed the German army in the back. In 1924, he became one of the first Nazis to be seated in the Reichstag.

Scheubner-Richter also was close to White Russian émigrés, and worked to bring about close cooperation between right-wing Russian émigrés and the Nazi Party. Through him, Hitler received the unqualified support of Gen. Vasili Biskupsky. In 1922, Biskupsky declared his support for Grand Duke Cyril, a pretender to the Russian throne. As a first cousin to Czar Nicholas II, he was a rightful heir to the crown. Both the Grand Duke and his wife, the Grand Duchess Victoria, took up the Nazi cause and gave generously.

There also are credible reports that Hitler traveled to Switzerland to raise funds during the hyperinflation. Even trifling sums in foreign currency were worth enormous sums in German marks.

In October 1923, Gen. Eric Ludendorff suggested to Fritz Thyssen that he attend a speech by Hitler. Thyssen, whose family owned one of Germany’s largest steel firms, was immediately struck by Hitler’s views, and began contributing money to the Nazi Party. In October he gave Ludendorff 100,000 gold marks (not the inflated paper German marks) to divide between the Nazis and the Oberland Freikorps.

Here lies the controversy and the need for a close look at Hitler’s rise to power. There has been a concerted effort in recent years to distance big business from support for the Nazis. Writers and historians try to downplay this connection and resort to deception. They base their argument on the size of Germany’s industries, saying that only a few qualified as big businesses. This is as absurd as defining big business in the United States today to be only the 30 companies in the Dow-Jones Industrial index. Some writers have defined big business in Germany so that less than 10 qualify.

The same writers, including Pool, try to minimize Thyssen’s contribution by noting it was divided between the Nazis and the Freikorps. This argument is weak and misleading. Today in the United States, it’s almost standard practice for a businessman or a corporation to contribute money to both parties to cover all possible outcomes, although the donations are seldom equal, and this practice is common across time and national boundaries. In fact, at the time of the Beer Hall Putsch in Germany, giving to multiple parties was especially prudent, since Germany’s proportional parliamentary system awarded seats in the Reichstag on total votes received, rather than a winner-take-all system. Thus, even minor parties won a voice in the Reichstag.

Moreover, the Freikorps helped fund the Nazis. A close look at Hitler’s trial reveals a close association between the two. Also, the Freikorps was a militia and not a political party. It did not fund other political candidates.

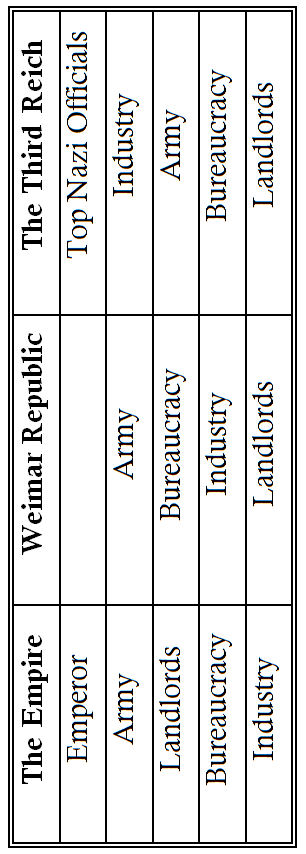

While the Nazis and Hitler were well known around Munich, they were unknown elsewhere. The Nazis had yet to seat their first representative in the Reichstag. Thyssen must have had an extraordinary degree of faith in the Nazis to make such a generous donation at a time of economic strife. The table below gives the composition of the Reichstag seats throughout the Weimar Republic.

SPD: Social Democrats; USPD: Independent Socialists; KPD: Communists; Centre Party: Catholics; BVP: Bavarian Peoples Party; DDP: Democrats; DVP: Peoples Party; Wirtschafts Partei: Economy Party; DNVP: Nationalists; NSDAP: Nazis.

After the Nazis’ November 1923 attempt at an armed coup d’état, the Beer Hall Putsch, the Bavarian government only halfheartedly tried to round up and arrest members of the Nazi Party. Anton Drexler and Dietrich Eckart were arrested, but Eckart was released after 10 days because of sickness and died a month later. Franz Guertner, the minister of justice, worked feverishly behind the scenes to ensure Hitler received a light sentence. Of more than 100 people for taking part in the putsch, Guertner decided to prosecute only 10: Hitler, Ludendorff, Ernst Pochner, Wilhelm Frick, Ernst Roehm, Friedrich Weber, Hermann Kriebel and three storm troopers - Brueckner, Wagner and Pernet, who were merely spearcarriers.

Frick had been Hitler’s secret agent inside the police department. Weber was the commander of the Oberland Bund. Kriebel commanded the Kampfbund, an amalgam of the Reich War Flag, the Oberland Bund and Nazi storm troopers. The Oberland Freikorps was the parent organization of the Oberland Bund, a participant in the putsch. There was extensive cross-membership between the Nazis and the Oberland Bund. Further, the Thule Society helped fund the Oberland Freikorps.

In essence, the Oberland Bund helped to provide Hitler with manpower for the Beer Hall Putsch. Looking at this evidence, the ridiculous claims by Pool and other writers that Thyssen’s donation to the Nazis is overrated are obvious. Thyssen’s donation went exclusively to Hitler and his thugs.

Hitler’s trial provides more evidence of his funding sources. Feb. 7, 1924, Herr Auer, vice president of the Bavarian Diet, testified:

The Bavarian Diet has long had information that the Hitler movement was partly financed by an American anti-Semitic chief, who is Henry Ford. Mr. Ford’s interests in the Bavarian anti-Semitic movement began a year ago when one of Mr. Ford’s agents, seeking to sell tractors, came in contact with Diedrich Eichart the notorious Pan-German. Shortly after, Herr Eichart asked Mr. Ford’s agent for financial aid. The agent returned to America and immediately Mr. Ford’s money began coming to Munich.

Herr Hitler openly boasts of Mr. Ford’s support and praises Mr. Ford as a great individualist and a great anti-Semite. A photograph of Mr. Ford hangs in Herr Hitler’s quarters, which is the center of the monarchist movement.

Shortly after Auer’s testimony, W.C. Anderson resigned and Ford experienced severe difficulties in doing business in Germany. Ford’s donation came amid Germany’s hyperinflation period, when foreign currency was especially valuable. The extent of the donation is unknown.

Further confirmation of Ford’s funding comes from an interview Hitler gave seven months before the Beer Hall Putsch to Raymond Fendick, a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. Fendick wrote:

We look on Heinrich Ford as the leader of the growing fascisti movement in America. We admire particularly the anti-Jewish policy, which is the Bavarian Fascisti platform. We have just had his anti-Jewish articles translated and published. It is being circulated to millions throughout Germany.

In 1924, Kurt Luedecke traveled to America to get more funding from Ford. Luedecke insists he was sent on the direct orders from Hitler. Luedecke had glowing remarks for Ford’s editor of the Dearborn Independent, William Cameron.

Further confirmation of Ford’s support for Hitler comes from newspaper articles. The Berliner Tageblatt made an appeal to the American ambassador to investigate the report of Ford’s financing of the Nazis, noting that Hitler had money to spend during the hyperinflation period when marks were worthless. The Manchester Guardian reported Hitler received more than moral support from two American millionaires.

While there is no direct proof, it can be surmised that the Guardian was referring to either the du Pont family or W. Averell Harriman. Irénée du Pont, heir apparent of the du Pont family, was a Hitler admirer who followed his career closely. The du Ponts quickly reestablished their cartel agreements with IG Farben as soon as World War I ended. Harriman traveled to Berlin in 1922 to set up the Berlin branch of W.A. Harriman & Co. George Herbert Walker was a director of the company; he was the father-in-law of Prescott Bush. Harriman and Thyssen had agreed to set up an American bank for Thyssen before 1924. The resulting bank, Union Bank, was seized from Prescott Bush in 1942 under the Trading With the Enemy Act.

The perplexing question of why American big businessmen would support Hitler at this early date has never been addressed. Before the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler was largely unknown outside the Munich area, even within Germany. Given Ford’s character as a miser who hated making donations to charities and organizations, why would he back a political party that had so far failed to seat a single representative in the Reichstag, at a time when the country was on the brink of a financial collapse? Only two explanations seem reasonable: Hitler’s strong anti-communist stance or his extreme anti-Semitism or Judeophobia. Both Harriman and Irénée du Pont were Judeophobes, although not fanatics like Ford. Throughout the 1920s, both U.S. foreign policy and trade policy show that American investors were sympathetic with Mussolini because of his anti-communist stance.

Hitler’s trial revealed he received $20,000 from Nuremberg industrialists. The most significant contributor was Emil Kirdorf. In a Jan. 3, 1937 article in the Preussiche Zeitung, Kirdorf hints at his early support for Hitler: “In 1923 I came into contact for the first time with the Nationalist Socialist movement … I first heard the Fuehrer in the Essen Exhibition Hall. His clear exposition completely convinced me.”

More evidence of Hitler’s early financiers comes from the records of the Kilgore Committee.

By 1919 Krupp was already giving financial aid to one of the reactionary political groups which sowed the seed of the present Nazi ideology. Hugo Stinnes was an early contributor to the Nazi Party. By 1924 other prominent industrialists and financiers, among them Fritz Thyssen, Albert Voegler, Adolph Kirdorf and Kurt von Schroeder were secretly giving substantial sums to the Nazis.

Except for Schroeder, all the people named above came from the large steel and coal trusts. Stinnes met with Hitler and Ludendorff on Oct. 25, 1923. Although no direct evidence is available, it appears Stinnes funneled money to Hitler through Ludendorff, one of the large industrialists who benefited from the hyperinflation. Indeed, many large industrialists in Germany benefited handsomely from the hyperinflation, lending creditability to the theory of an organized plot to relieve them of their millions in wartime debt, which they paid off with worthless, inflated marks. After Stinnes died in 1924, his son continued to support the Nazis.

The Nazi Party formed a bridge between the upper and the lower classes. While lower- and middle-class people filled the ranks of the SA, the upper class controlled and guided the policies of the party. Fascism as represented by the Nazis was a top-down movement by the elite to preserve their status.

More proof of Hitler’s powerful connections comes from the extremely lenient sentence he received. Article 81 of the German Penal Code declares: “whosoever attempts to alter by force the Constitution of the German Reich or of any German state shall be punished by lifelong imprisonment.” Ludendorff was found innocent for taking part in the coup attempt. Hitler received only five years in prison and was released six months after the trial, serving only a year from the time of his arrest. Minister of Justice Franz Guertner secured an early release for Hitler and legalized the Nazi Party, which the trial judge had banned. Guertner later served as minister of justice in the cabinets of Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher. Hitler kept Guertner in that position, even though he was not a party member and protested the Nazi perversion of justice. He died in 1941.

Less lenient sentences were handed out to others in secret trials conducted by the Weimar Republic during the 1920s. For instance, Walter Bullerjahn was sent to prison for 15 years for treason. The Allies had discovered that the arms maker Paul von Gontard had secretly cached an arsenal contrary to the Treaty of Versailles. Gontard disliked Bullerjahn and charged him with revealing to the Allies the fact he was secretly arming Germany. No evidence of any connection between Bullerjahn and the Allies was ever presented in court. Bullerjahn was one of hundreds of victims who received more severe sentences for far less serious crimes than an armed rebellion and coup attempt.

In jail, Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, first published July 18, 1925. By the end of the year, the first run of 10,000 was nearly sold out and a second printing was ordered. However, in the following year, sales dropped sharply, reviving only after Hitler seized power.

On Dec. 20, 1924, when Hitler was released from prison, he found the party in disarray and his leadership challenged. The court had seized his car and the party newspaper. He was banned from speaking in Bavaria and in most of Germany. The party had made good inroads into the Reichstag in the May 1924 election, gaining 32 seats, but it suffered stunning losses in the December election that year, losing more than half of the seats gained in the summer. The only good news for Hitler was that Guertner had quashed an effort to deport him.

By spring 1925, Hitler bought a new supercharged Mercedes-Benz for 28,000 marks. His only source of income after his release from prison was an occasional fee for newspaper articles he wrote. He also required a chauffeur who needed to be paid regularly. During the summer, Hitler spent much time at Obersalzberg in the Alps, traveling by car regularly from Munich. During this time, he came into more contact with the feudal princes. The Bavarian aristocrats were equally divided; half of them supported Hitler while the other half detested him. The divorced wife of the Duke of Sachsen-Anhalt began giving Hitler 1,500 marks a month from her alimony. Thanks to his increasing contacts with the princes and their generosity to the party, Hitler changed his program and came out in favor of restoring expropriated lands and property. This change caused a major split in the party. Even Joseph Goebbels denounced the idea, but by the end of the summer, Hitler was in full control.

After his release from prison, Hitler realized that his only path to power was through the ballot box, so he decided to work within the system. However, 1925-29 marked a period of slow growth for the party. Inflation was under control and the communist threat had subsided. Without these two threats, voters turned away from the radical Nazi Party. Nazi records show the number of dues-paying members steadily increased from 27,000 in 1925 to 108,000 in 1928, but the party records are suspect and the real figures may be only half those reported.

Hitler and Big Business

Authors such as James Pool and Henry Ashby Turner, who minimize and distort the support of big business for the Nazi Party, suggest that Hitler’s financing from 1925 - 29 came mainly from dues and speaking fees. Yet the number of dues-paying members was inadequate, and Hitler was banned from speaking in much of Germany. On the other hand, author Carroll Quigley lists the following industrialists as supporters of Hitler during this time: Carl Bechstein, August Borsig, Emil Kirdorf, Fritz Thyssen and Albert Vogler.

There is much evidence to support Quigley’s position. Even Turner is forced to acknowledge that Hitler started courting big business support. On June 20, 1926, the Essen newspaper Rheinisch-Westfalische Zeitung reported that two days before, Hitler spoke to a closed-door meeting of invited business leaders. Hitler closed the meeting to get around the Prussian state’s ban on public speeches. In the subsequent 18 months, he addressed three other such meetings. Hitler was softening his approach to big business thanks to past financial donations. By all reports, after these meetings the business leaders were in favor of Hitler’s views. The meetings grew in size from 40 for the first meeting to a high of 800 for the last one.

Turner tries to minimize big business participation in these meetings by claiming that no record of attendance has ever been found in the files of the big businessmen, and that some records would have survived. However, many of these big business leaders supported Hitler in secret, and the need for secrecy was mutual. Hitler had to avoid losing a large number of party members who opposed big business. The big business leaders had to maintain secrecy to avoid consumer boycotts. Ford’s business suffered badly after his support of Hitler became known, and the lesson was not lost on these savvy executives. In 1926, even the Bechstein piano firm dismissed Edwin Bechstein after reports surfaced in the press of his fraternization with Hitler.

Turner claims that an obscure man named Arnold, who held a managerial job at a midsize smelting firm, organized the first meeting. Then he assumes only people in similar positions were invited. It is unlikely that a group of midlevel managers from small to midsize firms meeting with Hitler would have attracted the attention of local newspapers. It also is unlikely Hitler would have traveled to Essen to speak at the request of midlevel business managers unless some prominent names were present.

Turner also tries to distance big business from the Nazis by suggesting that company donations were made by junior or middle-level management. While such an argument sounds reasonable, it is patently false. Almost no business even today allows such decisions by middle-level managers; such daring decisions would likely lead to the employee’s dismissal. As an example, Ludwig Grauert, the managing director of the Arbeitnordwest, the iron and steel industry association in the Ruhr, made a $100,000 loan to the Nazis after receiving permission from Ernst Borbet, another director of United Steel. After his boss returned and discovered the loan, Grauert was nearly fired. If Thyssen had not replaced the funds, Grauert would have been dismissed.

In 1927, Elsa Bruckmann, a Munich socialite, arranged a meeting between Hitler and Emil Kirdorf. Kirdorf was a fanatical nationalist and supporter of radical right-wing causes. During the four-hour meeting, Hitler downplayed his anti-Semitism and said the Nazi Party’s 25 points would not be implemented. Hitler rarely spoke of the 25-point program and, in later years, only spoke of it derisively. He presented himself as a defender of private enterprise and a supporter of an economy based on Darwinian principles that only the strong survive. Kirdorf suggested Hitler write down his thoughts in a pamphlet to spread secretly among business leaders. Hitler complied and Kirdorf printed the pamphlet, The Road to Resurgence, listing Hitler as the author. In October, Kirdorf offered Hitler further aid by inviting him to his home to meet with 14 of his friends.

It is unknown how many pamphlets of The Road to Resurgence were printed, but the circulation was extremely limited. Only one of the pamphlets has survived. It was found in the library of a major Ruhr industrial firm. In his shamefully apologetic diatribe to big business, Turner uses this fact to suggest the pamphlet was largely unread. However, as it was found in the library of a large industrial firm, it suggests that whoever received the pamphlet placed it there so others could read it. Further, it is equally probable that these industrialists passed the pamphlet within their own circle of friends. It is more likely these industrialists read the pamphlet eagerly, since they were intrigued by Hitler’s ability to rally the workers, along with his anti-socialist and anti-union views .

Hitler continued to meet with business leaders, often in secret, until his appointment as chancellor. Many times, these meetings were so secret that they would take place in a lonely forest glade on the side of an isolated road.

A complete list of Hitler’s financial backers may never be known. However, Walter Funk named many business leaders and industries as financial supporters of Hitler during his Nuremberg testimony: Georg von Schnitzler, a leading director of IG Farben; August Rosterg and August Diehn of the potash industry; Wilhelm Cuno of the Hamburg-Amerika Line, the shipping company seized from Prescott Bush for trading with the enemy; Otto Wolf, a powerful Cologne industrialist; and Kurt von Schroeder, a radical Nazi and Cologne banker. Also implicated were Deutsche Bank, Commerz Bank, Dresdner Bank, Deutsche Kredit Gesellschaft and Allianz, Germany’s largest insurer.

Many businesses chose to align with and support the Nazis after they gained power. Krupp and IG Farben were both executors of Goering’s Four-Year Plan to make Germany militarily self-sufficient by 1940. In April 1933, Gustav Krupp sought a private meeting with Hitler. Krupp agreed to become Hitler’s chief fund-raiser and chairman of the Adolf Hitler Fund. In return, Hitler promised to appoint Krupp as the Fuehrer of Germany industry. Through the years, Krupp contributed more than 6 million marks of his own money to the Nazis, and his correspondence shows that he enjoyed his job as chairman. It is common knowledge that after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, Krupp greeted people cheerfully with the Heil Hitler salutation.

In 1932, Kurt von Schroeder and Wilhelm Keppler formed the group known as “The Fraternity.” Members agreed to contribute an average of 1 million marks a year to Heinrich Himmler’s personally marked “S” account and the transferable, secret “R” account of the Gestapo.

While Hitler continued to meet with the industrialists, he allowed Gregor Strasser, Goebbels and Gottfried Feder to continue to beguile the masses with socialist views. Hitler never expressed any solid economic views of his own. He would tailor his speech to the audience. Speaking in front of industrialists, he would soften his anti-Semitism and denounce the Nazi 25-point program. In fact, Hitler never did support the 25-point program and referred to it only once in Mein Kampf, and then in a derogatory manner. Hitler continued to evolve the party away from socialism and was successful in convincing Goebbels to desert the socialist faction of the Nazi Party led by Strasser. This softening of the Nazi position on capitalism and private property is clearly seen in an Erklärung, a clarification of the party position issued April 13, 1928.

Since the NSDAP admits the principle of private property, it is self-evident that the expression “confiscation without compensation” merely refers to the possible legal powers to confiscate, if necessary, land illegally acquired, or administered in accordance with the national welfare. It is directed in the first instance against Jewish companies which speculate in land.

Besides receiving aid from German business leaders and the upper class of German society, Hitler and the Nazis received important support from corporate America, as shown in this excerpt from an interview with the American ambassador to Germany, William Dodd.

Certain American industrialists had a great deal to do with bringing fascist regimes into being in both Germany and Italy. They extended aid to help fascists occupy the seat of power, and they are helping to keep it there …

Propagandists for fascist groups try to dismiss the fascist scare. We should be aware of the symptoms. When industrialists ignore laws designed for social and economic progress, they will seek recourse to a fascist state when the institutions of our government compel them to comply with the provisions.

Dodd did not name any of the industrialists in the interview, but most historians believe he was referring to Henry Ford. Other foreign sources of support for Hitler came from Sir Henri Deterding, the founder of Royal Dutch Petroleum. Deterding was strongly opposed to communism and, as early as 1921, was a Hitler admirer. Deterding was interested in discovering those forces that would remove once and for all the dangers of social or colonial revolutions. At the inquiry into the Reichstag fire, Johannes Steel, a former agent of the German Economic Intelligence Service, testified to Deterding’s financial support for the Nazis. The Dutch press reported that Deterding had given Hitler about 4 million guilders. By the 1930s, Deterding began secret negotiations with the German military to provide a year’s supply of oil on credit. In 1931, Deterding made a 20 million pound loan to Hitler, allegedly for a promise of a petroleum monopoly once the Nazis were in power. In May 1933, Alfred Rosenberg, Hitler’s representative, met with Deterding, confirming the close link between big oil and the Nazis. In 1936, the board of directors forced Deterding to resign over his Nazi sympathies.

Despite Hitler’s successful effort in courting support from big business and industrialists, the Nazis remained a minor party until after the 1929 stock market crash. Owing to its huge burden of debt, Germany suffered more than other countries. In the 1930 election, the Nazis won 107 seats in the Reichstag, making it the second largest party. It became the largest party in the Reichstag in the July 1932 election, but still fell short of a clear majority. The depression brought about three short-lived governments, amid political intrigue and backroom deals. However, Hitler’s only visible gains from the 1930 election were meetings with the chancellor and the president.

Early in 1932, Hitler decided to run for president against Paul von Hindenburg. Two other candidates were on the ballot: Theodor Duesterberg, a nationalist, and Ernst Thaelmann, a communist. Hitler lost badly to Hindenburg, receiving just 30 percent of the vote to Hindenburg’s 49.6 percent. Hitler campaigned on the slogan “Freedom and Bread.” Since Hindenburg did not receive a majority of the vote, a runoff was held a month later. In it, Hitler received 37 percent of the vote to Hindenburg’s commanding 53 percent.

The final year of the republic was marked by the failure of three separate governments: Bruening, von Papen and Schleicher. The last government of Schleicher lasted only 57 days. Party leaders became embroiled in political plots, forming transient alliances. Von Papen, who like Schleicher was heavily involved in political intrigue, later played a prominent role in Hitler’s appointment as chancellor.

The intrigues also involved big business leaders and other prominent industrialists. On Jan. 26, 1932, Hitler spoke to 650 industrialists at the Düsseldorf Industry Club to gain their trust and support. While the Nazi Party was the largest party in the Reichstag after the July 1932 election, Hitler was still denied the office of Chancellor.

Business viewed von Papen’s government favorably because it allowed the unilateral breaking of union contracts and lower wages. Estate owners received subsidies, and land reform was stopped. Businesses received tax rebates, but workers received no tax relief.

Politically, the von Papen administration existed only because of the secret support of the Nazis. In return, von Papen granted three Nazi demands. He dissolved parliament, which triggered the July 1932 election; he reinstated the SA and SS, which had been banned; and he disposed of the Prussian government, removing the last obstacle for the Nazis. After the July election, negotiations between von Papen and Hitler broke down, as both sought the office of chancellor.

As early as September 1932, leading Ruhr industrialists told Gregor Strasser that they had suggested to the highest offices in Berlin that Hitler be appointed chancellor. By November, business leaders took a more active role in securing a Hitler government by sending a petition seeking his appointment as chancellor. The petition originated with members of the Keppler Circle and was signed by Kurt von Schroeder, Vogler, Thyssen and others. The petition was less than successful in the business community, as the Nazis became more radical in their demands throughout the summer, into the fall and through the November election.

The radicalism cost Hitler and the Nazi Party dearly. They lost 34 seats in the Reichstag and their source of funding from business leaders was severely cut. Nevertheless, Hindenburg asked Hitler to form a government under two conditions. Hitler refused the offer, resulting in Schleicher’s appointment as chancellor. But business leaders soon opposed Schleicher, who restored the inviolability of union contracts and launched a large-scale public works policy to reduce unemployment.

With the arrival of a new year, the Nazi Party’s future looked dim. Hopes were dashed by the November election, and the party experienced severe financial difficulties. However, business leaders turned against the new Schleicher government and arranged a meeting between Hitler and von Papen. The objective of the meeting at the Cologne home of Kurt von Schroeder was to form a new government led by Hitler and von Papen.

Baron von Schroeder was a member of the most influential group in Germany, the Herrenklub, as well as the Thule Society. He later held several high positions in the Nazi government and directed ITT’s Germany subsidiaries. Moreover, von Schroeder had extensive financial contacts in New York and London. He was a co-director of the Thyssen foundry with Johann Groeninger, Prescott Bush’s New York bank partner. Schroeder also was vice president and director of Prescott Bush’s Hamburg-Amerika Line.

The meeting took place in utmost secrecy on Jan. 4, 1933 with two Americans present: John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles. The Dulles brothers were there representing their client, Kuhn, Loeb & Co., which had extended large, short-term credits to Germany and needed assurance of repayment from Hitler before committing to support him. Goebbels recorded the success of the meeting in his diary on Jan. 5, 1933: “If this coup succeeds, we are not far from power ... Our finances have suddenly improved.”

Hitler now had the backing of both von Papen and the business leaders. Facing pressure from these quarters, Hindenburg relented and appointed Hitler as chancellor on Jan. 30, 1933.Von Papen assumed the vice-chancellor position.

Herein lies the danger of creeping fascism. Hitler was appointed chancellor thanks to a backroom deal, with the blessing of international bankers. He rose to power by electoral rather than revolutionary means. However, Hitler’s appointment as chancellor was not due solely to support from big business and from political intrigue. A flaw in the German constitution, which did not account for a stalemated parliament, aided his rise to power. Power in Germany was concentrated in the office of the president, headed by Hindenburg, who had the authority to appoint cabinets and chancellors. Beginning in 1930, Hindenburg began appointing chancellors who were not beholden to parliament, and circumvented it by granting them the emergency powers given to the president by the constitution. Presidential decrees enacted almost all national laws, including the power to tax, because parliament was hopelessly deadlocked in petty political bickering.

Americans should take special note of the concentration of power in Germany in the president’s office. US presidents increasingly are relying on executive orders. These executive orders bypass Congress and are most likely unconstitutional, since they usurp the power to rule by presidential decree. Most alarming are the series of executive orders concerning a state of emergency. They give the US president the right to seize the media, farms, private transportation, airlines, medical facilities and housing, and even to conscript citizens into organized work battalions.

In Germany, the Hitler-von Papen government was a coalition between the NSDP and the DNVP, plus big business and landowners, since it was their support of the Nazis that persuaded Hindenburg to appoint Hitler.

The membership of the Nazi Party came mostly from the lower and middle classes: 7% upper class, 7% peasants, 35% workers, and 51% middle class. The largest single occupational group was the elementary school teachers. These percentages reflect the structure of German society. Germany had a large middle class before Hitler assumed power, although the real wealth of the country was concentrated in a few hands.

In 1925, Professor Theodor Geiger conducted an extensive study of the class distribution in Germany. He divided German society into five classes.

While there is no direct comparison between Geiger’s study and later breakdowns of party membership by class, the figures indicate the Nazi party had a widespread appeal in the upper class. The small percentage of capitalists indicates the stratification of Germany society, with wealth concentrated in just a few families. Although the middle class membership numbers suggest widespread support for the Nazis, the reality is many of the professions, such as schoolteachers, were required to join the party. Figures for the 1925 class structure and the party membership point to fascism being a top-down movement.

Hitler became chancellor only after he eased the fears of big business leaders and assured them of his support. Fascism is generally a desperate reaction by the elite to preserve their power and wealth in periods of economic crisis and political strife. The resurgence of fascism since the 1980s may be linked to the stresses of shifting from an industrial to an information-based economy. This is especially troubling in the United States, where U.S. supremacy is threatened by increasing dependence on imported oil and manufactures. The fortunes of the American elite depend on an oil-driven economy and the ability of the U.S. to project power with a navy, army and air force running largely on oil.

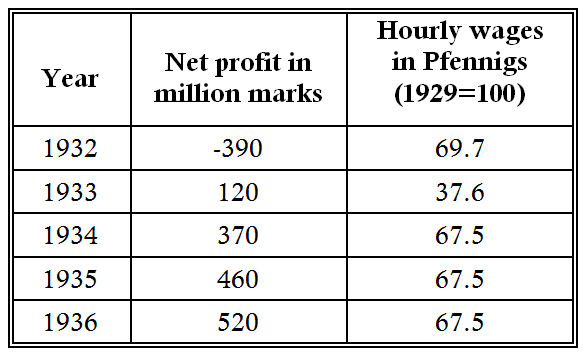

Politicians and political speeches promise everything; however, the real character of any regime can only be determined by its actual policies. Hitler and the Nazis were no different. They used socialist rhetoric to attract followers, but soon turned on them. Hitler’s Nazi economic policies up to the invasion of Poland revealed the true character of fascism without distortion by the fog of war.

The Nazi Government and Big Business

Within his first month as chancellor, Hitler faced a crisis. He proposed to dissolve parliament and hold new elections. Hugenberg, the leader of the DNVP party and a member of Hitler’s cabinet, rejected the idea of a new election. Big business backed Hitler, but only after a Berlin meeting between the Nazis and the Reich Association of German Industry. The industrialists gave their support only after Hitler assured them of the need for a fundamental cleavage between democracy and private capital. Private ownership of the means of production could only be ensured once democracy was destroyed. The elderly Krupp welcomed Hitler’s remarks and looked forward to a strong, independent state and business prosperity. Once Hitler gained the industrialists’ support, Goering appealed to the group for financing for the new election. Three million marks were required; the Ruhr industrialists supplied 1 million.

By choosing to finance the March 1933 election for the Nazis, big business became a full partner of the Third Reich. The support came at a crucial time for Hitler. If business leaders had withheld their support, Hitler’s government would have failed.

After a week in office, Hitler got a new decree from Hindenburg to remove the Prussian ministers. Their powers were conferred on von Papen; Goering received the police authority. The Nazis already controlled the national police through the Interior Department, headed by Wilhelm Frick. By Feb. 7, 1933, Hitler had secured control of the national and Prussian police. He then launched a violent, two-pronged attack against the opposition. Goering and Frick, under a cloak of legality, worked from above, while Capt. Ernst Roehm, head of the storm troopers, worked from below, with no pretext of legality. Goering and Frick removed all noncooperative police officials and replaced them with Nazis, usually storm troopers. On Feb. 4, 1933, Hindenburg signed an emergency decree, giving Hitler the right to ban meetings and the press.

The opposition was attacked from below in violent assaults, often leaving one or more people dead. Despite the violence inflicted by storm troopers, it was obvious the week before the election that the Nazis faced strong opposition. Under these circumstances, a plot was hatched to burn the Reichstag and blame the communists. The Nazis fingered a mentally incompetent Dutchman, Van der Lubbe, who was left wandering about the Reichstag after the fire. The following day, Feb. 28, 1933, Hindenburg signed an emergency decree suspending all civil liberties. The Nazis arrested all communist members of the Reichstag and thousands of others. Communist and social democrat newspapers were suspended for two weeks.

The regular German courts acquitted the four communists charged with setting the blaze and convicted poor Van der Lubbe. Several people knew the truth, including Ernst Oberfohren, a Nationalist Reichstag member, but they were murdered in March and April. Goering had most of the Nazis involved in the plot killed during the blood purge of June 30, 1934.

Despite the Nazis’ drastic measures, the March 5, 1933 election failed because they succeeded in drawing only 43.9 percent of the vote. The new Reichstag convened March 23 at the Kroll Opera House. To achieve a majority, the Nazis excluded all the communists and 30 socialists from the session. The remaining members were then asked to pass an enabling act giving the government the right to rule by decree for four years. Since the act required a two-thirds majority, it could have been defeated if only a small group of Center Party members voted against it. But the measure passed 441-94, with the social democrats forming a solid minority.

Next, the Nazis issued a series of revolutionary decrees ordering the diets of all German states be reconstituted in proportion to the national election, excluding all communists. A similar measure followed in local governments. An April 7, 1933 decree gave the Hitler government the right to name a new governor for each German state. The governors were empowered to dismiss state governments, including judges. The law was used to seat Nazi governors and judges.

Hitler declared May 1 to be a national holiday and gave a speech on the dignity of labor. The next day, the SA seized all union buildings and offices, arrested all labor leaders and sent most of them to concentration camps, betraying the duplicity of the Nazi character. In July, Hess promised to break up the great department stores, but no action was ever taken.

By July 1933, all political parties except the Nazis were banned. Wholesale and retail trade associations were consolidated into the Reich Corporation of German Trade, under the direction of Nazi Party member Adrian von Renteln. Von Renteln became president of the German Industrial and Trade Committee, a union of all branches of the chamber of commerce. Previously, the chamber of commerce had been a semipublic corporation.

Labor was coordinated without opposition, except from the communists. However, by the spring of 1934, the SA was becoming an acute problem. It was calling for a second revolution and economic reforms favorable to labor and damaging to the heart of the Nazi support - big business. Further, the SA was calling for incorporation into the Reichswehr, with each officer holding the same rank as he had in the SA.

On June 21, 1934, Hindenburg ordered General Werner von Blomberg to use the army to restore order if necessary. Hitler quickly arranged a deal with the top military leaders to destroy the SA in return for his appointment as president, once Hindenburg died. Hitler’s previous support from a faction within the military should not be overlooked in this deal. On June 30, 1934, Hitler arranged a meeting of SA leaders in Bad Wiessee. The SS under Hitler’s command arrested and shot most of the leaders at the meeting in the middle of the night. Goering did the same to SA leaders in Berlin and murdered most of his personal enemies. In all, the Nazis killed several thousands in the blood purge.

The threat from the army to restore order had been serious, but not overwhelming, since the SA outnumbered the Reichswehr 10 to 1. The choice facing Hitler was clear: support the “second revolution” and socialism, or destroy it. His decision to decapitate the SA and with it any hope for social reforms shows how fascism served big business. Any supporters of a second revolution lucky enough to survive were driven underground.