Operation Northwoods

The mention of the CIA commonly brings to mind images of James Bond, spy thrillers, covert warfare and Cold War Warriors fighting the evils of communism. But more often than not, the reality of CIA plots are images of the gang that could not shoot straight. Examples abound of the absurd actions of both the CIA and its forerunner, the OSS.

During WWII, the OSS became wrongly convinced that the Japanese were deathly terrified of bats. Thus, to help the war effort, Donovan of the OSS decided to test drop bats out of aircraft over the southwestern deserts before risking planes over Japan. The only fly in this ointment was the poor little critters froze almost instantly on release in the stratosphere and shattered like fine china on hitting the ground. After killing a few million bats in the skies of the southwestern desert, the plan was dropped.

Harvey’s “hole in Berlin” is another example of some rather shortsighted thinking by our intelligence agencies. In 1954, under the direction of Bill Harvey, a 1,476-foot tunnel into East Berlin was dug to install a phone tap on a Russian communication center. After almost a year, the Russians discovered the tap, allegedly while repairing a cable. What was not mentioned was the American spies had become so accustomed to their comforts that they turned off the air-conditioning to the tunnel during the chilly winter season. The tunnel was marked on the surface by a telltale strip of bare ground over its entire length in an otherwise snow-covered landscape.

Perhaps the most bizarre case of misguided CIA misadventures is the wired kitty. During the Cold War, the CIA decided to enlist a cat to spy on the Soviets. The plan was for the cat to sit on a window ledge or bench and record any conversation. The cat went under the surgeon’s knife to insert microphones, batteries and a transmitter. Agents tested the cat extensively in the lab and found it walked off the job when it was hungry. So the cat underwent surgery again and a wire was inserted to suppress its hunger. After more lab testing, the kitty was ready for field testing. Agents took the cat to a nearby park and released it, hoping to hear various conversations. Instead, they heard a screech of brakes. The cat decided to cross the street and was run over by a taxi, leaving the agents to scrape up the body and the highly classified wiring.

On March 11, 1961, President John Kennedy held a meeting with his advisers about what became known as the Bay of Pigs fiasco. (The CIA recently admitted it was responsible for the mistakes made.) The original invasion was to take place some 100 miles east of the Bay of Pigs. After Kennedy demanded a site that would be more conducive to a night landing, the CIA turned to the Bay of Pigs. The original landing site picked for what was supposed to be a secret night landing was the equivalent of downtown Los Angeles. Overflights of the new landing area revealed dark forms just under the surface in the shallows of the bay. CIA experts decided they were seaweed. However, they turned out to be coral reefs that could rip the bottom out of small landing craft, or leave troops high and dry like sitting ducks for any gunners onshore.

A recent episode of CIA bungling took place in the bombing of Serbia during the Kosovo crisis. By mistake, the United States bombed the Chinese Embassy. President Clinton was quick to apologize to the Chinese, and the CIA stepped forward and admitted its error. The maps had not been updated in four years. More information surfaced later. A lower-level CIA employee had warned repeatedly of the possible misidentification of that target site, but was ignored. There may have been more to the bombing than a bad map. The London Guardian reported that NATO deliberately targeted the embassy because it was sending messages for the Yugoslav army.

The embassy bombing points to two problems. First, the agency works in total secrecy; even its budget is classified. It may be years or even decades before the truth is finally known. Second, many questioned whether the CIA was deliberately misleading President Clinton. The agency was known to pass on less-than-credible documents to higher policy making officials. During a November 1995 Senate Select Committee, it was revealed that CIA officials passed on more than 35 reports without disclosing the information came from known Soviet double agents. Between 1986-94, the CIA passed on at least 95 reports based on information from double agents without revealing the doubtful source or accuracy.

At other times, the CIA deliberately defied presidential orders. During the Kennedy administration, the agency defied orders to close a training facility for Cuban guerrillas in Louisiana. Kennedy resorted to using the FBI and other agencies to close it.

Today, the CIA is perhaps the most despised agency in the government. It has overthrown governments worldwide, including those of allies such as Canada and Australia when they turned toward liberalism. In other operations, the agency has conducted gruesome operations such as Project Phoenix in Vietnam. Far too often, elements in the agency have hatched bizarre plots to achieve an agenda. One such plot was Operation Northwoods, which evolved out of the Bay of Pigs fiasco. (See Appendix 13.) While Operation Northwoods was a military operation controlled by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, it illustrates the problem with covert operations and the broader intelligence community.

In early November 1961, Robert Kennedy held a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House in which he announced that all responsibility for dealing with Cuba was to be shifted from the CIA to the Pentagon. This shift reflects the continuing distrust of the CIA by the Kennedy administration. The Right Wing savagely attacked the Kennedy administration for being soft on communism after the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion. John F. Kennedy fired Allen Dulles as CIA Director over the fiasco.

Edward Lansdale and Lyman Lemnitzer directed the new Cuba operation, code-named Mongoose. Lansdale was an OSS agent during WWII who then transferred to the Army. In 1960, he was a one-star general and the deputy director of the Pentagon’s Office of Special Operations. Lemnitzer was a career military officer who served as an aide to Eisenhower during the war and was appointed Chief of Staff in 1957. He helped create the NATO stay-behind network, turning Nazi agents into spies against the USSR, and infiltrating Nazi war criminals into Latin America in the 1950s.

Lansdale and Lemnitzer quietly set about exploring the possibility of doing what they wanted to do: a full-scale invasion of Cuba. The last vestiges of McCarthyism were still strong in the ranks of the military and the Right Wing. Many ranking officers believed communist agents infested the government. The John Birch Society was at its zenith. The firing of Gen. Walker for indoctrinating his troops with Birch Society propaganda in April 1961 reenergized the Right.

Walker’s discharge triggered a study by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee into the dangers of right-wing extremism in the military. Its report warned of considerable danger in the education and propaganda activities of military personnel. Among the key targets were Kennedy’s domestic social policies that the Right Wing deemed communist-inspired. The report concluded with a chilling warning of a possible revolt by senior military officers, and called for examination of Lemnitzer’s extreme right-wing connections. Lemnitzer became increasing paranoid after Kennedy took office; he resented the youthful president. Further, Lemnitzer did not trust civilian command, which he believed interfered with the proper role of the military.

The roots of Operation Northwoods extend back to the last days of the Eisenhower administration. The Cold War was at one of its hottest points after the Soviet Union shot down Francis Gary Powers’ U2. Eisenhower wanted desperately to invade Cuba. On Jan. 5, 1961, he told Lemnitzer and other aides in the Cabinet Room he would move against Cuba before the inauguration if only the Cubans would give him a good excuse. Eisenhower then suggested that if Castro failed to provide an excuse, perhaps the United States could manufacture something that would be generally accepted. Eisenhower suggested feigning a bomb attack or an act of sabotage against the United States. It was a dangerous suggestion from a president with only a few days remaining in office.

Approved and signed by all the Joint Chiefs, Operation Northwoods called for acts of terrorism to be committed on American soil. Various plans included shooting innocent people on American streets, sinking boats of Cuban refugees and a violent wave of terrorist attacks launched against Washington, D.C., Miami and other cities. Using phony evidence, innocent people would be framed and Castro would be blamed.

On Feb. 26, 1962, Robert Kennedy ordered Lansdale to stop all covert planning against Cuba and to concentrate on intelligence gathering, due to the increasingly outrageous nature of Operation Mongoose. However, Lemnitzer continued with Operation Northwoods: a raft of dirty tricks like blaming Castro if the rocket carrying John Glenn into space exploded, sabotaging ships at Guantanamo or fake attacks against the base or civilians in the U.S. There was no limit to Lemnitzer’s fanatical fancy. Other schemes called for bombings, hijackings, disguising a drone as a passenger plane and blowing it up, and fake attacks against the U.S. Air Force.

On March 15, 1962, President Kennedy told Lemnitzer there was almost no possibility the United States would use military force in Cuba. However, Lemnitzer persisted in his plans against Cuba to the point of insubordination. Within months, President Kennedy denied Lemnitzer a second appointment as Joint Chief of Staff and transferred him to Germany, effectively removing him from causing any further damage and ending his career.

Years later, President Gerald Ford appointed Lemnitzer to the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. Lemnitzer’s aide, Brig. Gen. Craig, who helped plan Operation Northwoods, was promoted to major general and spent three years as chief of the Army Security Agency, NSA’s military arm.

The Origins of the CIA

Understanding how the CIA and the intelligence-military community evolved into a hideous monster plotting to terrorize American civilians and menace freedom worldwide requires a close look at the careers of those who shaped the agency.

On Oct. 1, 1945, President Truman ordered the OSS disbanded. Bill Donovan sealed the fate of the agency when he hired liberals and socialists to fill its ranks. By the end of the war, the OSS was split into two factions in Europe. One faction vigorously hunted Nazi criminals and worked hard to decartelize Germany, while the other, led by Allen Dulles, worked equally hard to cover up war crimes and to undo any attempts at decartelization. The hard Right and Nazi sympathizers clamored to rid the nation of a spy agency full of communists.

The pool of experienced intelligence agents was reassigned to the military and other government agencies. Some, like Allen Dulles, returned to private life. Those assigned to the State Department were soon forced to return to the private sector when Congress failed to provide any funding for their positions.

On Oct. 22, 1945, three weeks after Truman’s order, Secretary of War Robert Patterson created the Lovett Committee, chaired by Skull and Bonesman Robert Lovett, to advise the government on the postwar organization of U.S. intelligence activities. The new agency, which consulted with the armed forces, was to be the sole intelligence collection agency in foreign espionage and counterespionage. It had its own secret budget. On Nov. 14, 1945, Lovett appeared before the Secretaries of State, War and Navy, and pressed for a virtual resumption of the wartime OSS.

On Jan. 22, 1946, President Truman issued an executive order setting up a National Intelligence Authority, and under it, a Central Intelligence Group, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. In 1947, Congress passed the National Security Act, which mandated a major reorganization of the U.S. government’s foreign policy and military establishments. The act, which took effect on Sept. 18, 1947, combined the departments of War and Navy into the single cabinet position of the (so-called) Department of Defense, and established the National Security Council and CIA.

Since 1980, there has been a steady stream of headlines indicative of America’s involvement with the Nazis. Summaries from some late 1990s headlines follow:

Billions of German Marks from German taxpayers are being paid for “victim” pensions. These pensions are paid to as many as 50,000 war criminals - on top of their regular pensions. One notable recipient was Wilhelm Mohnke, a Hitler confidant and commandant of the Führer bunker. He also had a role in executing 72 POWs during the Battle of the Bulge. Germany has only reluctantly agreed to halt such payments.

The prosecution of Aleksandras Lileikis as a war criminal by the government of Lithuania.

Kazys Ciurinskas, a retired Indiana contractor who served as a member of the 2nd Lithuanian Schutzmannschaft Battalion, a mobile Nazi killing unit, faces deportation for lying on his immigration papers about his involvement with the Nazis during WWII. Kazys’ battalion in October 1941 murdered over 10,000 people in Byelorussia

Five U.S. banks: Chase, J.P. Morgan, Guaranty Trust Co., Bank of the City of New York and American Express all turned over the accounts of Jewish customers to the Nazis during the occupation of France.

In an article appearing in Newsweek dealing with the return of the heirless assets, the cooperation of American corporations with the Nazis is exposed. Recently declassified documents show that at least 300 American firms continued to do business with the Nazis during the war.

The articles suggest a faction of Americans played a much greater role in aiding Hitler and the Nazis than commonly thought. While the widespread belief is that only a handful of American companies aided the Nazis, the Newsweek excerpt implicates more than 300 American corporations in wartime acts of treason.

Congress passed a bill to release all documents about war criminals. However, some agencies, such as the State Department, the Department of Defense and the CIA, are still raising objections, citing national security. Full disclosure of all documents about Nazi war criminals proved too embarrassing to several American corporations, powerful elite families, politicians, government agencies and programs.

In September 2000, the CIA admitted for the first time that it employed ex-Nazis. The story was only carried on the UPI wire. In the article, the CIA admitted that it employed Gen. Gehlen and his intelligence network after WWII. The acknowledgment confirmed perhaps the most widely known secret of the CIA and passed largely unnoticed. The more interesting aspect of the CIA-Nazi connection is how these former Nazis have molded foreign and domestic policies at the highest levels of government. The agency is guilty of sanitizing the records of other war criminals so they could come to the United States, then covering up these operations from Congress, federal investigators and the American public.

ODESSA

Besides the Vatican ratline, the Nazis had their own organizations devoted to helping war criminals flee Europe. The organization of former SS members, better known as ODESSA, was one part of the Nazis’ plans to escape Europe. Hollywood has embellished the fabled network, which was well organized and financed with stolen loot. While the exact origins of the network are unknown, some assign its origins to the Red House meeting in 1944. Other names for ODESSA were Die Spinne, the spider; Kamradenwerk, Comradeship; der Bruderschaft, the Brotherhood.

One person known to be associated with ODESSA was Otto Skorzeny. Skorzeny’s war exploits were legendary, resulting in the Allies declaring him the most dangerous man in Europe after the end of the war. Skorzeny surrendered to American forces in May 1945 and was interned at Dachau. During the war, Skorzeny trained the Werewolves, who formed the nucleus of the postwar Nazi underground and were instrumental in establishing the ratlines out of Europe.

The Allies believed the underground Nazi Werewolves functioned as commandos, conducting sabotage raids and assassinating any German who became too friendly with the enemy. There is unmistakable evidence that the Werewolves did assassinate some Germans aiding the Allies. However, it appears their primary function was to aid Nazis escaping Europe, which places the origins of the ODESSA network before the end of the war and perhaps as part of the plans evolving from the Red House meeting in 1944.

The American Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) placed moles inside the camps holding Nazi prisoners. In Operation Brandy, CIC moles determined there was a well-organized, illegal POW mail service. People living close to the internment camps were eager to help the POWs escape and find money. To gain further information about the underground Nazi ratline, a CIC mole arranged for his escape with two others from Dachau. The experience confirmed the existence of the ODESSA network and clearly identified Skorzeny as its director. Polish guards at Dachau were found to be part of the network, as were some of the drivers hired to operate army trucks between Munich and Salzburg.

After reaching Salzburg, the ODESSA ratline connected with the Vatican’s string of monasteries reaching to Rome. There was a second ratline, ODESSA North, stretching through Norway, Sweden and Denmark. An underground network of SS veterans and Werewolves smuggled Nazi war criminals overland to ports, where they sailed to Argentina or Spain. Argentine diplomats were instrumental in easing traffic along this route.

The wholesale emigration of Nazi war criminals out of Europe could not have taken place without the approval of U.S. officials in Germany. Skorzeny was still in U.S. custody in 1948, even after being found innocent of war crimes. An American military lawyer who liked him successfully defended him; and later bragged about tricking the court to get him acquitted. However, Skorzeny still faced other charges in Czechoslovakia. Warned by American officials that a Czech government appeal to extradite him might succeed, Skorzeny plotted his escape with the help of American officials.

After escaping from the Darmstadt internment camp, Skorzeny made his way to a farm in Bavaria rented by Countess Ilse Luthje, a niece of Hjalmar Schacht. Skorzeny later married the countess before making his way to Spain. While there, Skorzeny maintained constant contact with Gehlen. The ongoing relationship between the Gehlen organization and the CIA was emblematic of a pivotal alliance with ODESSA. Former U.S. intelligence officer William Corson describes Gehlen’s organization as a well-orchestrated diversion. The primary role of Gehlen’s organization was to neutralize U.S. intelligence so the Nazis could continue their quest for world fascism by using the ODESSA network.

In September 1948, German police noted a Skorzeny movement had sprung up in the U.S. zone and was spreading across Germany. British intelligence concluded that Skorzeny was working for U.S. intelligence and building a sabotage network. Declassified documents indicate American intelligence officials seriously considered enlisting Skorzeny, but Maj. Sidney Barnes killed the idea. Skorzeny’s notoriety would expose the United States to too much potential embrassment.

Little else is known about the shadowy ODESSA network beyond Skorzeny’s association with it, but it appears that Francois Genoud, a Swiss resident of Pully on Lake Lausanne, functioned as the banker. In 1934, Genoud joined the Swiss pro-Nazi National Front. Two years later, he traveled to Palestine and befriended Amin al-Husayni, the pro-Nazi religious and political leader of Palestinian Muslims, who had been appointed Grand Mufti of Jerusalem in 1921 by the Zionist High Commissioner Herbert Samuel. In 1940, Genoud set up a nightclub in Lausanne to serve as a covert operation for the Abwehr, the German counterintelligence service. In 1941, his Abwehr contact, Paul Dickopf, sent him to Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Belgium. As part of his Abwehr services, Genoud dealt in currency, diamonds and gold, to name a few.

In 1942, Dickopf went underground with help from Genoud. Ironically, from 1968-72, Dickopf was president of Interpol. At the end of the war, Genoud represented the Swiss Red Cross in Brussels.

Using banking contacts established while working for the Abwehr, Genoud set in motion networks that later became known as ODESSA, which functioned principally for the transfer of millions of marks from Germany into Swiss banks. By 1955, Genoud was an adviser, researcher and banker for the Arab nationalism cause. He set up AraboAfrika, an import-export company that served as a cover for disseminating anti-Israeli propaganda and the delivery of weapons to the Algerian National Liberation Front. He also made investments for Hjalmar Schacht, a key postwar intermediary between Germans and Arabs. When Algerian independence was proclaimed in 1962, Genoud became director of the Arab Peoples’ Bank in Algiers.

Beginning in the 1960s, Genoud helped finance and supply weapons to numerous Arab terrorists. Genoud also was a close friend of David Irving. On May 30 1996, Genoud committed suicide by taking poison.

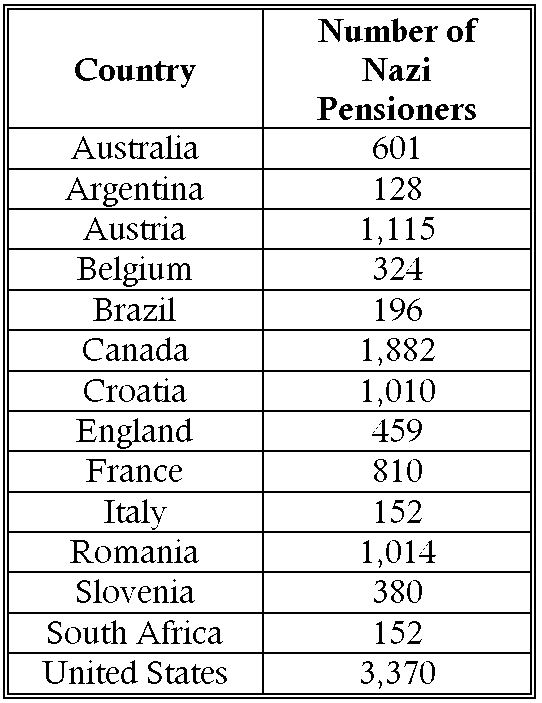

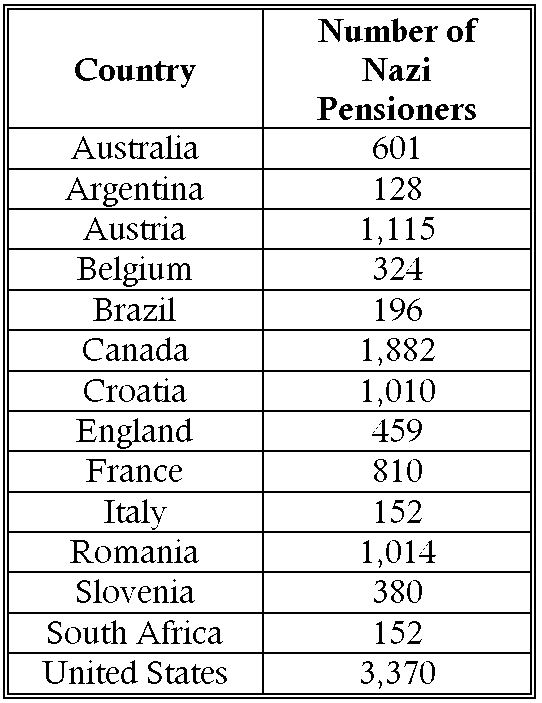

Some sense of the scope of the CIA’s involvement with the Nazis can be gathered from the table below. It presents the number of former Nazis receiving pensions from Germany, as estimated by the Wiesenthal Center. SS pensions are typically around $560 a month, three times the reparations paid to Holocaust victims. It is significant to note that more than half of those receiving pensions live in either the United States or countries of the British Empire that were committed to bringing Nazis to justice. While not all the pensioners were war criminals, a good number of them had their records sanitized.

By the end of the war, many of the New Dealers who vigorously opposed fascism were replaced with more conservative officials. Nazi sympathizers now had support in the government from the growing ranks of conservatives in the Roosevelt administration and Congress. Growing support for ex-Nazis continued through the Eisenhower administration.

The Nazis also had a comeback plan of their own. It counted on support from collaborators in foreign countries, including the United States. Evidence of the plan comes from captured documents, shown in Appendix 10. The Nazis hoped to convince Americans that Roosevelt’s policy of prolonging the war would drive Germany towards communism. This would help Dewey win the election and sign a separate peace with Germany.

At the end of the war there were two interconnected drives by the military and intelligence operations. The first was to acquire as much German technology as possible; the other was to heighten America’s phobia about communism.

American fascism has always had its roots in Wall Street and the financial elite of America. That same cadre arranged a marriage between ex-Nazis and the CIA. Previous chapters have already examined how they were able to sabotage the 4Ds program and Safehaven. The Safehaven operation was quickly stripped from the Treasury Department and Morgenthau’s influence, and turned over to the State Department. There, Dulles’ friends quickly shredded the Treasury Department’s list of interlocking companies and blocked further investigations.

Records show that at the end of the war, CIC had two large Civilian Internment Centers, code named Ashcan and Dustbin. Both Ashcan and Dustbin served as central internment camps for POWs and Nazi collaborators. CIC identified many American internees who had remained in Germany and aided the Nazis. Much of the overwhelming, indisputable evidence for charging them with treason came directly from captured German records. But suddenly, on orders from the Department of Justice, they were released. Those in the department who spoke out were fired. The attorney who helped bury the treason cases was later promoted.

Central to the Wall Street alliance with the Nazis and the OSS-CIA was Allen Dulles. Dulles played a pivotal role in helping American investors cover up their dealings with the Nazis. His reassignment to Bern from New York was a continuation of Roosevelt’s secret plot, allowing British intelligence to spy on Americans believed to be aiding the Nazis. Both postings placed Dulles in a position where he would be most tempted to aid his clients. While the evidence would be inadmissible in court, it was incriminating and caused a widespread public cry for full investigations.

However, some time after Dulles arrived in Bern, the Nazis tipped him off that he was being watched. It is commonly believed the leak occurred when Vice President Henry Wallace told his brother-in-law, the Swiss Minister in Washington, about Roosevelt’s secret spying. Unfortunately, the Nazis had recruited the head of the Swiss Secret Service, and in Berlin, they were soon reading any information given to the Swiss. Wallace was one of only a few in the Roosevelt administration aware of the British spying. Many of the old spies believe Roosevelt dumped Wallace from the 1944 ticket due to the leak.

The British wiretap operation originally was conducted by a special section of Operation Safehaven. Before his death, Justice Goldberg confirmed Dulles’ appointment was a setup and insisted the Dulles brothers were traitors.

The British operation was extensive and included spying on Joseph Kennedy and Nelson Rockefeller. The spying on Kennedy netted his radio operator, who was tried in secret by the British and imprisoned until the end of the war. Rockefeller’s appointment to an intelligence post for South America also was part of Roosevelt’s scheme. Others included James Forrestal and industrialists such as Henry Ford.

Many of Rockefeller’s dealings with the Nazis were conduited through shell corporations in Latin America. The dealings were facilitated by his appointment to the post of Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs by Forrestal in 1940, at his own request. This was the position of the top spy in Latin America. Rockefeller proposed to Harry Hopkins that England and Hitler fight each other to the death so that, regardless of who won, the United States could pick up the pieces to increase corporate America’s economic influence. Rockefeller was only concerned with corporate America’s interests. His definition of totalitarianism was limited to the USSR.

Once Nelson Rockefeller accepted the position, he told his staff that their job was to use the war to take over Latin American markets. Rockefeller also used his position to see to it that the Nazis got anything they wanted in South America, such as refueling bases, while forcing the British to pay cash. In addition, he effectively blackmailed Britain by threatening to withhold or block raw materials and food shipments. Rockefeller’s chief aim was to drive the British out of Latin America and monopolize the markets. In each country, he set up coordinating committees composed of reactionary executives from Standard Oil of New Jersey, United Fruit and General Electric.

Rockefeller never bothered to help the war effort; by 1945, a third of the countries in South America had still not declared war on the Nazis. Further, a pro-Nazi bloc of countries, led by Peron of Argentina, was actively involved in helping hide escaping war criminals. Peron was a friend of none other than Allen Dulles.

Allen Dulles a Traitor

Dulles reacted quickly after the Nazis told him of the Safehaven wiretaps. In January 1944, he closed down the pipeline by telling both sides that their secret messages were being intercepted. But there is a much more sinister and serious implication of Dulles’ warning to the Nazis that their codes had been broken. Before the Battle of the Bulge, the Nazis began a radio blackout and relied solely on couriers to deliver orders. As a result, allied intelligence was completely blind to the Nazi battle plan for the Battle of the Bulge. Dulles’ warning was a clear act of treason.

Dulles attempted to use Gero von Gaevernitz as a secret courier, but he also was under surveillance. Both Dulles and Gaevernitz were charged with laundering the assets of the Nazi Hungarian Bank through Switzerland after the end of the war, under the guise of a series of film companies. Both men managed to avoid prosecution by angry denials and subterfuge.

With the end of the war rapidly approaching, the tip-off that the Allies were intercepting his messages presented Dulles with a special problem. He could no longer use Swiss banks to launder the assets of his American clients and Nazi conspirators which were trapped in Germany. Dulles briefly shifted his money-laundering business to the Central Bank of Belgium. A significant part of the Nazi gold stocks was routed through banks in Belgium, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein. All three countries refused the Allies’ postwar demand to examine their files. The Normandy invasion soon shut down this route for Nazi flight capital, leaving most of the American investors’ capital still at risk in Germany. Dulles then shifted his money laundering across Austria and into Italy, where his Vatican contacts were waiting to complete the shipping to Argentina.

At the end of the war, U.S.-British Combined Chiefs of Staff investigated Dulles for dereliction of duty and refusal to follow orders. Those military records have conveniently disappeared. The charges stem from Dulles brokering a deal for the surrender of Karl Wolff. Dulles was ordered to break off talks with Wolff, but continued ignoring orders, even to the point of rescuing him from Italian partisans. Wolff eventually was granted amnesty with help from Dulles, despite being the highest-ranking SS officer in Italy and a war criminal. Wolff eventually went free, even though he was Himmler’s chief of staff and had arranged contracts for slave labor. In addition, Wolff was the chief Nazi sponsor behind Treblinka. According to information released in 2000 by the CIA, Wolff was deeply involved in deporting Italian Jews to Auschwitz.

Allen Dulles faced other serious allegations after the war. His effectiveness as a spy located in Bern was questionable at best, as shown by the following quote from a cable from Washington to Dulles in January 1944:

We think it is essential that you be informed at once that almost the entire material supplied disagrees with reports we have received originating with other sources, and parts of it were months old. There has been degeneration of your information which is now given a lower rating than any other source. This seems to indicate a need for using the greatest care in checking all your sources. The Bern estimate of German forces is most inaccurate and misleading. It contains grievous errors regarding locations and also includes reports of non-existent divisions. Only 30 of the divisions reported are correctly identified and the remaining divisions reported are either incorrectly located or do not exist. In more than 50 instances, the classification of divisions by type is wrong.

Both John Foster and Allen Dulles benefited greatly from trade with the Nazis before war broke out. Allen was a director of Schroeder Bank and John Foster sat on the IG Farben board. There also is evidence that both of the Dulles brothers made large, indirect contributions to the Nazi Party as the price to pay for influence in the Third Reich.

When the Sullivan & Cromwell office in Berlin was shut down in 1934, the Dulles brothers merely shifted their business to front men, increasing their profits as Hitler’s rearmament program advanced. The buyout of Anaconda Copper by the German Giesche conglomerate is an example of how the Dulles brothers structured deals for the benefit of their clients. Anaconda bought a large block of stock in Giesche, which was secured with Anaconda’s 51 percent share of Giesche’s interests in Polish Silesia. Giesche provided the Nazis with funding in the early 1930s, but after they invaded Poland, he was forced to sever the American tie or face a Nazi takeover. Allen Dulles represented Anaconda. Giesche bought back its shares from Anaconda with loans from Swiss banks represented by the Dulles brothers. The Swiss banks then held stock in the German banks that arranged the loans. The net effect was to use Swiss bank secrecy as a shield from both Hitler and the American government.

The treachery of the Dulles brothers was boundless. In 1940, a three-way deal was structured with their help. Allen Dulles represented Nazi buyers like IG Farben. John Foster Dulles represented the German bankers and Spanish financiers. Jack Philby represented the Saudi sellers. To understand fully the relationships in this deal requires looking at the career of Allen Dulles after WWI. Dulles was stationed in Istanbul and ran a network there that amassed a good deal of information about the potential wealth of Arabia. Jack Philby was the British Secret Service’s head of intelligence for Transjordan. During this period, Philby was, in effect, rehabilitating Dulles. During WWI, Dulles was recruited by British intelligence in Bern and fell victim to a German honey trap. In return for sexual favors, he arranged for his mistress’ employment in the American Legation’s secret code room. The British discovered the intelligence leak and arrested both Dulles and his mistress. Dulles denied the treason and vowed to help the British if they saved his neck.

Under Philby’s tutorage, Dulles’ reputation as an observer solidified and he returned to Washington in 1922 to head the Near East Division. Meanwhile, Philby helped direct anti-Jewish terror and, in 1923, created the Arab Legion. In 1924, Philby aligned behind Ibn Saud. After Saud’s forces captured Mecca and Medina, Philby became an adviser to the house of Saud. At the same time, Allen Dulles resigned from the State Department. He found private intelligence work to be more profitable, especially when he and his brother worked out deals with the Saudis through his friend Philby.

All three men - Dulles, Philby and Ibn Saud - were known to harbor an intense hatred of Jews. Ibn Saud was the leader of the extremist Wahhabi sect of Moslems and the Arab leader who united the Arabian Peninsula.

In 1936, James Forrestal brought Socal and Texaco together with the help of Dillon and Read Vice President Paul Nitze, who drew up a plan to pool the assets of the two companies “east of the Suez.” Caltex became the parent company of Arabian-American Oil Co. They also involved a common shareholder, IG Farben. The Dulles brothers’ client, Hermann Schmitz, was president of American IG, which later changed its name to General Aniline and Film (GAF). Forrestal sat on the board of GAF, which owned stock in both Socal and Standard, and was effectively controlled by IG Farben.

Behind the complex web of paper in the deal, Dulles’ Nazi client, IG Farben, had Forrestal on its payroll and Forrestal’s client, Caltex, had Saudi oil. Philby held the deal together and the Nazis had a supply of Mideast oil. The deal worked well until the entry of the United States into the war. While Harry Truman declared the buna rubber deal between Standard and IG Farben looked like treason, Standard Oil avoided all but a minor fine. Standard’s principal line of defense against the government’s charges was simply blackmail. Arthur Goldberg confirmed that Dulles was behind the blackmail threat to cut off the Mideast oil supply to the United States, which was already suffering from gasoline rationing.

Dulles also threatened to cut off Britain’s oil supplies after the British began leaking information about IG Farben. In their threat to Britain, the Dulles brothers expressed concern that British propaganda about IG Farben might involve large American companies like Standard Oil and hinder the war effort.

The blackmail by Standard Oil resulting from the Dulles-Philby connection was not the end of their treachery. Ibn Saud was pro-Nazi. To stay out of British prison as a Nazi sympathizer, Philby added another angle to the 1940 deal by keeping Saudi Arabia neutral during the war for a bribe. In effect, the Saudis were paid to not pump oil for either Britain or Germany. In June 1941, James Moffett of Caltex tried the same shakedown on Roosevelt. To guarantee Saudi Arabia’s oil would not fall into Nazi hands, the American government paid more than $6 million a year to Ibn Saud. However, Roosevelt turned the matter over to the British. Soon after, all Saudi oil wells were capped with cement.

After the U.S. entry in the war, rumors continued that Caltex was shipping oil to the Nazis. The Dulles brothers used their cronies in the State Department to drag the investigation out for two years. Then Forrestal proposed to Roosevelt that Caltex’s loyalty to the government could be bought. They argued the British were becoming too influential in the Mideast. Roosevelt was faced with a hopeless situation; he could never get Congress to approve a government investment in Aramco. He was forced to do the next best thing and added Saudi Arabia to the Lend-Lease program to keep Middle East oil from the Nazis.

The Dulles brothers had little cause to worry about the seizure of GAF, the American subsidiary of IG Farben. They had collaborators on both sides of the case. James Forrestal was vice president of GAF. The Alien Property Custodian Leo Crowley was on the payroll of the New York branch of the Schroeder Bank. Schroeder Bank was the depository for GAF, and both Forrestal and Allen Dulles were directors. John Foster Dulles even arranged his appointment as legal counsel for the Alien Property Custodian while representing another IG Farben subsidiary against the custodian.

Crowley appointed Victor Emanuel to the boards of GAF and General Dyestuffs after their seizure by the Property Custodian. Emanuel, in turn, appointed Crowley to head Standard Gas and Electric at $75,000 a year. Emanuel was a director of Schroeder Bank. After James Markham replaced Crowley as Property Custodian, Emanuel appointed Markham as a director of Standard Gas. George Edward Allen was another individual owing debts of gratitude to Emanuel for appointments to private directorships after President Truman appointed Allen head of the Reconstruction Finance Corp.

Crowley also chaired the Foreign Economic Administration and sent Col. Carl Peters to Germany as part of the 4Ds program to decartelize Germany. Peters was the former president of Synthetic Nitrogen, a director of Chemnyco and an official for Advanced Solvents, all IG Farben subsidiaries. Peters was indicted in 1939 in two synthetic nitrogen cases kept secret from the public. He was eventually removed from his post in Germany by the Army’s counterintelligence unit.

Moreover, the section on chemicals in Crowley’s Program for German and Industrial Disarmament was written by Col. Frederick Pope, a director of American Cyanamid, which was indicted and fined for conspiring with IG Farben in 1946.

The Dulles brothers had little to fear from the Department of Justice. Shortly before his death, Roosevelt told a visitor that he should have fired Attorney General Francis Biddle. In May 1945, before a public hearing conducted by Sen. O’Mahoney, Biddle and Assistant Attorney General Wendell Berge testified that executives of corporations who signed and executed illegal cartel agreements with IG Farben were innocent of any attempt to injure national security and did not present any moral problem.

Biddle resigned the day before Howard Ambruster was to testify before O’Mahoney’s investigation into his tenure as attorney general. Rumors at that time stated Assistant Attorney General Norman Littell forced into the record proof of Biddle’s connections to Thomas Corcoran. Corcoran previously was employed by the New York law firm of the late Joseph Cotton, President Hoover’s Under Secretary of State who approved a massive loan to Germany when the Nazis rose to power. Corcoran later became legal counsel to the Reconstruction Finance Corp.

The Dulles brothers were able to engineer a massive cover-up of their Nazi dealings. Their web of intrigue extended to all corners of the government. In the 1930s, they created an incredible interlocking financial network between Nazi corporations, American Oil and Saudi Arabia. Perhaps the best-known deal arranged by them was between IG Farben and Standard Oil of New Jersey. IG Farben was the second-largest shareholder in Standard Oil of New Jersey, after John D. Rockefeller.

The Navy captured Nazi documents concerning the Nazi oil cartel, Kontinentale Öl AG, headed by former Reichsbank officer Karl Blessing. Dulles personally vouched for Blessing to protect German oil interests in the Mideast. Blessing and Konti were the missing Nazi link between Ibn Saud and Armco. If Blessing had been exposed, he could have taken a lot of people down with him, and the entire deal struck between the Dulles-Philby team and the Nazis would have unraveled.

The Navy assigned the documents to a young naval officer for review. Allen Dulles contacted the officer and told him to remain quiet about what he had seen and, in turn, he would arrange financing for his first congressional campaign race. This was the beginning of Richard Nixon’s political career. In 1947, Nixon privately pointed out that confidential government files showed that Alger Hiss was a communist and one of John Foster Dulles’ foundation employees. After the 1948 election, Nixon became Dulles’ congressional mouthpiece. When McCarthy went too far in his communist witch hunt, it was Nixon who steered CIA Director Bedell Smith away from the intelligence community.

The Republicans and Nazi War Criminals

An early supporter of Nixon’s political career was Prescott Bush. Prescott Bush had employed the Dulles brothers to hide Nazi ownership in numerous companies. Prescott Bush also was instrumental in selecting Nixon as the vice presidential candidate in 1952. Nixon returned the favor by helping George H. W. Bush’s political career. George H. W. Bush has described Nixon as his mentor.

Concealing the Konti documents was far from the end of Nixon’s aid to former Nazis. For example, Nicolae Malaxa was the supplier of arms to the Iron Guard in Romania and a business partner of Goering, who was later convicted of war crimes in that country. In 1948, he formally applied for permanent U.S. residency and faced a blizzard of legal challenges. In 1951, Nixon introduced a bill in the Senate that would have granted him resident status. It failed. Later that year, Malaxa formed a shell corporation named Western Tube in Nixon’s hometown. It shared a mailing address with Nixon’s former law firm. The firm applied for a certificate of necessity to get top wartime priority for its material and personnel. Nixon supported granting residency to Malaxa because he was indispensable to Western Tube. Yet Western Tube never produced a single product. Others who aided Malaxa in his legal battles include John Foster Dulles and former Undersecretary of State Adolph Berle.

Nixon’s fraternization with Nazis continued beyond his congressional terms and into his presidency. In fact, a lasting result of Nixon’s aid to Nazis has manifested in every election since 1972, including the 2004 election. Nixon, like Allen Dulles, believed the pro-Nazi émigrés from Eastern Europe would be useful in getting out the vote. Both Dulles and Nixon believed Jews were responsible for Dewey’s loss to Truman. In 1972, Nixon’s State Department spokesperson confirmed to his Australian counterpart that ethnic heritage groups were useful in getting out the vote in several key states.

The Republican Ethnic Heritage Groups had their roots in Eastern Europe during WWII. In each of the countries, the SS funded or set up political action groups and militias. A partial list follows:

Hungary - Arrow Cross

Byelorussia - Byelorussian Brigade

Romania - Iron Guard

Bulgaria - Bulgarian Legion

Latvia - Latvian Legion

Ukraine - Ukrainian Nationalist

Often these groups were more brutal and savage than the SS. Many formed active military divisions: 14th Galician, 15th and 19th divisions of the Waffen SS. All the military units from these groups played an integral role in the genocide in Eastern Europe.

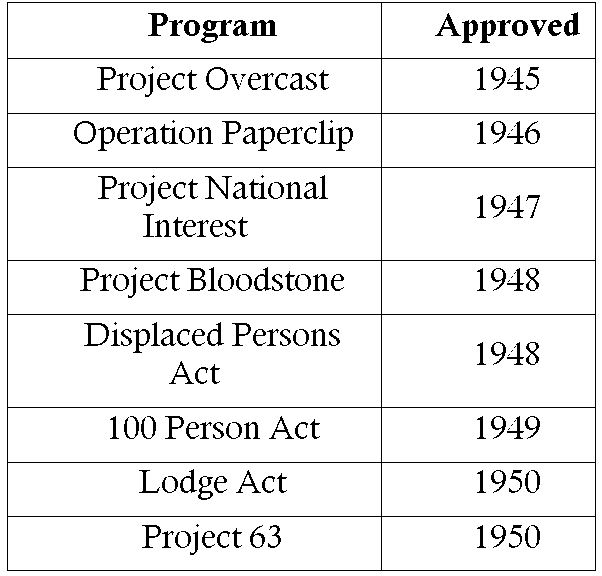

Nixon’s first attempt at using ethnic groups was in 1952 when he formed an Ethnic Division in the Republican National Committee. In 1953, immigration laws changed to admit Nazis, including former SS members. Nixon oversaw the new immigration policy. In 1968, Nixon promised he would create a permanent ethnic council if he won the presidential election. Until this time, the Ethnic Division surfaced only during presidential campaigns. After winning the 1968 election and appointing George H. W. Bush as chairperson of the Republican Party, Nixon delivered on his promise to the fascists. Laszlo Pasztor organized the Republican Heritage Groups Council.

During the war, Pasztor was a leader of the Arrow Cross in Hungary. Once the Arrow Cross seized power, it conducted a terror campaign against Jews until deporting them to the concentration camps. Many members of the Arrow Cross were tried and executed for war crimes. Pasztor served as a liaison in Berlin between the Nazis and the Arrow Cross government of Hungary. He was convicted of collaborating with the Nazis and served a prison sentence. Pasztor, who arrived in the United States during the 1950s and joined the Republican Ethnic Division, was one of its leaders in the 1968 Nixon-Agnew campaign.

Pasztor claims he selected others for the council with similar backgrounds. The only groups approached by Pasztor from Eastern Europe were those with ties to the Nazis. There is a high degree of correlation between CIA domestic subsidies to fascists during the 1950s and the leadership of the Republican Party’s ethnic heritage groups. During the 1950s, while Allen Dulles directed the CIA, many immigrants registered as Republicans, and groups like the Byelorussian Republican Committee emerged. The same fascist leadership received covert CIA subsidies to buy printing presses, and dominated many of the ethnic campaign groups. The subsidy program ended after the Church Committee investigations of the mid-1970s.

The Republican Party cannot be ignorant of the fascist background of the leaders of its Ethnic Groups because Jack Anderson did a series of reports in the 1970s exposing them. According to old spies, President Ford appointed George H. W. Bush CIA Director to fend off any further congressional investigations of Nazis in the United States.

Pasztor has several connections to right-wing extremist groups, such as the Heritage Foundation, the Free Congress Foundation and the World Anti-Communist League. In 1985, he gave up his seat on the Republican Ethnic Council in favor of an American-born ethnic in order to make it easier for the Group Council, an umbrella organization of ethnic heritage groups, to oppose the Justice Department’s Nazi-hunting unit. In 1988, Pasztor was forced to resign from the George H. W. Bush presidential campaign after his past Nazi connections were exposed. He was one of several former Nazis serving on the Bush campaign team. However, Pasztor remains closely connected with the Bush family, as this letter from Laura Bush reveals. Clearly, the Bush family sees nothing morally wrong in associating with known Nazi war criminals.

October 3, 2002

Mr. Laszlo Pasztor

National President Emeritus

National Federation of American Hungarians

717 Second Street NE

Washington, D.C. 20002-4307

Dear Mr. Pasztor,

My thanks to you and the National Federation of American Hungarians for Stephen Sisa’s book, The Spirit of Hungary. I hope you will extend to the membership my appreciation, especially for the kind inscription.

You are kind to think of me, and I am grateful for your generosity.

With best wishes,

[SIGNATURE]

Laura Bush

Pasztor is typical of the immigrants from Eastern Europe admitted under the Bloodstone project. The Nazis’ pasts were either buried or forgotten, and once admitted to the United States, the CIA provided them with subsidies. During the 1950s, they were recruited politically by Nixon and gradually assumed a dominant role in the Republican Party and right-wing foundations. Pasztor’s career outlines the timeline, from the 1950s to the present White House.

Most of the eastern European immigrants were not Nazis, but many admitted to the United States during the late 1940s-50s were. The continuing shift to the right in America aided Dulles’ efforts to enlist Nazi immigrants. The shift was marked by the removal of those who vigorously opposed fascism.

Operation Mockingbird

In September 1951, Robert Lovett replaced George C. Marshall as Secretary of Defense. Averell Harriman was named director of the Mutual Security Agency, making him the U.S. chief of the Anglo-American military alliance. A central focus of the Harriman security regime in Washington, from 1950-53, was organizing covert operations and “psychological warfare.” Harriman, with his lawyers and business partners, Allen and John Foster Dulles, wanted the government’s secret service to conduct extensive propaganda campaigns and mass-psychology experiments in the United States and paramilitary campaigns abroad.

The Harriman security regime created the Psychological Strategy Board (PSB) in 1951 with Gordon Gray as director. Gordon’s brother, Bowman Gray Jr., chairman of R. J. Reynolds, was a naval intelligence officer, known around Washington as the “founder of operational intelligence.” Gordon Gray was a close friend and political ally of Prescott Bush, and a leader in the eugenics movement in the 1920s-30s.

Shortly before the 1952 election, while the country was firmly in the grip of McCarthyism, the CIA launched a massive multimillion-dollar media blitz. The publicity campaign was designed to legitimize the expansion of U.S. Cold War operations in Europe. In essence, it was a psychological war against the American people. The program was guided by a theory of liberationism, and a major feature was the portrayal of former Nazis as freedom fighters against the USSR. The CIA’s propaganda campaign inside the United States was clearly illegal, but the agency managed to cloak its role. The forefront of this campaign was known as Crusade for Freedom, which generated massive amounts of propaganda.

Several other groups functioned under the Crusade for Freedom umbrella, including the Free Europe Committee, which it funded. Gen. Lucius Clay led the fundraising campaign for the Free Europe Committee and later served as one of its first directors with Allen Dulles, C.D. Jackson and Adolf Berle.

While both Nixon and Dulles believed the pro-Nazi émigré groups were useful to get out the vote, the first to use them in an election was Arthur Bliss Lane. He used the Crusade for Freedom to generate enthusiasm among the émigré groups for the Republican Party in the 1952 election. By playing on the nation’s phobia of communism, Republicans campaigned on a program of liberation rather than the containment policy of Truman and the Democrats.

Republican tactics in the émigré communities were almost indistinguishable from the CIA’s Crusade for Freedom. Lane’s specialist in the Ukrainian community was Vladimir Petrov, a Nazi quisling city administrator of Krasnodar, during the time gas trucks were introduced and used to kill at least 7,000.

There is no evidence that these émigré groups were useful in swaying election results. They do point to Republican Party’s continued association with fascism. As recently as 1988, several George H. W. Bush campaign employees were forced to resign once their past Nazi connections were revealed.

Dulles was able to use this illegal covert CIA propaganda campaign, casting ex-Nazis as freedom fighters, to open U.S. immigration doors. After the 1952 election he had a willing aide in Vice President Nixon.

By using foundations such as the Ford Foundation as fronts to wage the Crusade for Freedom, CIA involvement in domestic politics went undetected in the 1950s. A 1976 congressional investigation revealed the CIA funded nearly half of the 700 grants in international activities by the principal foundations. The Ford Foundation not only acted as a front for CIA propaganda campaigns, but also served to undermine the Left.

Looking at some of the past directors of the Ford Foundation from the 1950s, the connection is obvious. Paul Hoffman, who served from 1950-52, had been an administrator of the Marshall Plan. Richard Bissell served as foundation president from 1952-54, then left to become a special assistant to Allen Dulles in January 1954. Replacing Bissell was John McCloy, former High Commissioner of Occupied Germany, who set up a three-person panel to ease the foundation’s connection to the CIA.

Frank Lindsay was another CIA operative who came to work for the Ford Foundation in 1953. Lindsay was an OSS veteran. As Deputy Chief of OPC from 1949-51, he was responsible for setting up the “stay-behind” groups in Western Europe. Waldemar Nielsen joined Lindsay at the foundation, where he became a staff director. Throughout his stay at the Ford Foundation, Nielsen was a CIA agent. In his various guises, Nielsen worked closely with C.D. Jackson, associated with the Psychological Strategy Board.

The foundation gave $500,000 to Bill Casey’s International Rescue Committee and large grants to another CIA front, the World Assembly of Youth. The Ford Foundation is one of the largest donors to the Council on Foreign Relations. The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), founded in Washington in 1947, expanded its international program in 1958 after receiving a large grant from the Ford Foundation. On ICA’s board of trustees was William Bundy, a member of the CIA’s Board of National Estimates and son-in-law of former Secretary of State Dean Acheson. His brother, McGeorge Bundy, became president of the Ford Foundation in 1966, coming straight from his job as Special Assistant to the President in Charge of National Security. As special assistant, McGeorge Bundy duties included monitoring the CIA.

The Rockefeller Foundation also served the CIA. Both John Foster Dulles and later Dean Rusk were presidents of the foundation before becoming Secretaries of State. John McCloy and Robert Lovett served as Rockefeller trustees. Nelson Rockefeller’s service as head of South American intelligence and his central position in the foundation cemented the close link with the CIA.

The Ford and Rockefeller foundations are not the only ones that acted as CIA conduits. Former OSS agent and future CIA Director William Casey founded the Manhattan Institute. After the war, Casey also worked for another CIA front group, the International Rescue Committee.

Dulles’ propaganda efforts in the 1950s were massive. Besides the Crusade for Freedom, they included Free Europe, Radio Free Europe and many other programs. One measure of the scope of Dulles’ effort was the CIA’s $5 million contribution to anti-communist education through the crusade. While $5 million seems trivial today, at the time it exceeded all the money spent by both sides in the Truman vs. Dewey 1948 election. In 1952, Ronald Reagan became a fundraiser for the Crusade for Freedom. But Reagan was tied much more deeply to the military intelligence apparatus, as the following quote indicates:

In 1952, at MCA, Actors’ Guild president Ronald Reagan - a screen idol recruited by MOCKINGBIRD’s Crusade for Freedom to raise funds for the resettlement of Nazis in the U.S., according to Loftus - signed a secret waiver of the conflict-of-interest rule with the mob-controlled studio, in effect granting it a labor monopoly on early television programming. In exchange, MCA made Reagan a part owner. Furthermore, historian C. Vann Woodward, writing in the New York Times, in 1987, reported that Reagan had fed the names of suspect people in his organization to the FBI secretly and regularly enough to be assigned an informer’s code number, T-10. His FBI file indicates intense collaboration with producers to “purge” the industry of subversives.

The Gehlen Network

One of the first Nazis brought to America, and perhaps the one who exerted the most influence over U.S. policy, was Gen. Reinhard Gehlen. Gehlen was the Nazis’ most senior intelligence officer on the Eastern Front. He began planning his surrender to American forces as early as the summer of 1944. Like all senior Nazis seeking to surrender to the United States rather than the Soviets, he offered something of value to U.S. forces in exchange for freedom from prosecution as a war criminal. Such Nazi offers were characterized by alibis that downplayed their roles in the war and war crimes.

In early March 1945, Gehlen and a small group of his most senior officers microfilmed the vast holdings on the USSR of the Fremde Heere Ost (military intelligence section of the German general staff). They sealed the microfilm in watertight drums and buried them in the Austrian Alps.

On March 22, 1945, Gehlen and his top aides surrendered to CIC and were taken to Camp King near Oberursel in the American zone. Capt. John Bokor, the assigned interrogator, was reportedly anti-Nazi, but claimed a great deal of knowledge about the Soviet Union and sensed the Soviets as a threat. As the two men became friends, Gehlen gradually revealed his secret microfilms and an embryonic espionage underground inside the Soviet Union. Bokor was interested in Gehlen’s information, but faced several obstacles. For one, the Yalta agreements required turning over Nazis from the Eastern Front to the Soviets in exchange for help in the return of American POWs liberated by Stalin’s advancing forces.

Bokor continued on his own accord and kept Gehlen’s offer secret from other CIC officers. With the help of Col. William Philip, chief of the CIC interrogation center at Camp King, Bokor arranged for seven of Gehlen’s senior officers to be transferred to Camp King. There, Gehlen and his senior officers set up a “historical study group” as a cover. Gehlen’s microfilms were shipped to the camp without the knowledge of the CIC’s chain of command. Bokor feared that if he reported Gehlen’s existence too soon, he would be exposed to hostile actions from the Pentagon and military command in Frankfurt.

By the end of the summer, Bokor won the support of Gen. Edwin Sibert and Walter Bedell Smith. Bill Donovan and Allen Dulles also were aware of Bokor and Gehlen. Dulles had been tipped off about Gehlen from one of his double agents inside the German Foreign Office. OSS was jockeying for control of Gehlen and his microfilms.

Sibert shipped Gehlen and three of his aides off to Washington in August 1945 for debriefing. By December, Sibert had authority to continue at his own risk. In other words, Sibert had permission to continue with Gehlen, but if anything went wrong, the U.S. government would deny any knowledge of the operation.

Dulles’ OSS Secret Intelligence Branch had direct contact with Gehlen. Frank Wisner, a former Wall Street lawyer and OSS agent, headed the coordinating team. It is unclear how much President Truman knew about Gehlen, since those documents remain classified. However, the Soviets raised vigorous protest over Gehlen at Potsdam, so it is certain Truman was at least aware of the plans to use his intelligence.

Within a year, the United States set Gehlen’s organization up near Pullach in a former Waffen SS training facility. He handpicked 350 former German intelligence agents to join him; their numbers eventually grew to 4,000 undercover agents. Gehlen’s organization evolved into Germany’s equivalent of the CIA, the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND).

The swift recruitment of Gehlen and his rapid rise in the Western intelligence community was largely a result of U.S. fears of the Soviet Union. Once American Nazi sympathizers realized Germany had lost the war, they began stoking fears of communism and the dangers posed by the Soviet Union. The Nazis comeback plan rested on provoking a conflict between the Soviets and the U.S. To this end, Gehlen was a loyal Nazi, as suggested in the quote below:

Their (Gehlen’s organization) object was to commit the U.S. occupier on the German side and exploit the differences between Washington and Moscow in order to save the Germans from the worst consequences of the war begun by and lost by the Hitler regime.

As early as the beginning of 1947 Gehlen had confided to one of his staff that he was reckoning on the possibility of war between Russia and America; even should there be no armed conflict, he said Europe faced a decade of growing tension. Meanwhile he was toying with a fantastic notion - that the Russians and Americans would tear each other to pieces and so give Germany the opportunity to create a new order in Europe.

The extreme fear of the Soviets at the end of the war was largely illusory and more a product of vivid imaginations rather than anything of substance. Russia suffered immensely during the war, sustaining far more casualties than any other country.

The Ukraine and other eastern areas of the country suffered from two scorched earth policies of the retreating forces. Eisenhower once remarked to an aide that it would take several years before the Soviets would threaten Europe because it was ripping up the railroad tracks in Germany and shipping them back to Russia. Without the railroads, there was no way for the Soviets to move a massive number of troops forward for an invasion of Europe. Moreover, there is evidence that Stalin wanted peace after the war. On his return to Washington, Roosevelt’s envoy to Moscow, Donald Nelson, indicated Stalin proposed a trade plan for the postwar period. The plan was for the United States to provide Russia with finished goods, such as agricultural equipment, cars, household appliances and similar items in return for raw materials.

Gehlen is perhaps the man most responsible for starting the Cold War. At first, the military was skeptical of Gehlen and his reports. However, because of the meddling of Allen Dulles and postwar rivalries between the OSS and the Pentagon’s Military Intelligence Service, Gehlen soon became the leading expert on the Soviets.

In the postwar period, all branches of the military and the intelligence community suffered budget cuts. Col. John Grombach headed the Military Intelligence Service in the postwar period, and was competing for scarce funds with the OSS’s Research and Analysis branch. In 1945, to eliminate the OSS branch, Grombach had his men pore over captured German files looking for evidence that the agency was soft on communism. He found some, including one middle-level employee who joined the Communist Party a decade before and failed to disclose it on his application. He also found several university professors recruited by the OSS who had ties to liberal and left-wing organizations. Moreover, the OSS downplayed negative reports about the USSR and the Katyn Forest massacre to preserve the Allied coalition.

Grombach then leaked his information inside the Pentagon and to right-wing members of Congress. As a result, Congress broke the OSS’s Research and Analysis branch into 17 divisions, effectively immobilizing it. With the elimination of the research and analysis group, the hard-liners were firmly in control and Gehlen’s information was readily accepted. At the time, U.S. intelligence on the USSR was essentially an empty file. Even rudimentary information on the rail or road system was lacking. Gehlen was free to fan the flames of the Cold War. It’s now known that his estimates of Soviet troop strength were wildly exaggerated. Paul Nitze admitted that a full third of the Russian divisions in Europe were under strength; another third existed only on paper.

A former CIA chief analyst of Soviet military capabilities, Victor Marchetti, now admits that during the 1950s, Gehlen also played a part in the missile gap crisis. It was Gehlen’s reports to the CIA that first triggered the alert. Walter Dornberger, another former Nazi admitted to the United States, added more fuel to the fire by publishing speculation that the Soviets might attack from the sea using short-range missiles floated in canisters. However, U2 surveillance flights failed to detect any increase in the number of ICBMs that Gehlen claimed the Russians deployed.

On July 30, 1946, Chamberlin, the Army Director of Intelligence, proposed a plan to smuggle 30 ex-Nazi experts on the USSR into the United States as part of a group of 1,000 scientists. The Army wanted to shut down Operation Paperclip because of the expense of custodial duties and surveillance over the scientists. Chamberlin wanted desperately to save the Paperclip project. In response , Clay issued his famous telegram to Washington suggesting a Soviet invasion of Europe was imminent:

For many months based on logical analysis, I have felt and held that war (with the Soviets) was unlikely for 10 years. Within the last few weeks, I have felt a subtle change in the Soviet attitude … which now gives me a feeling that it may come with dramatic suddenness.”

Clay’s telegram was quickly leaked to the press and whipped into a full-blown war scare.

In a series of secret conferences with Gen. Clay in late 1947, Gehlen claimed the Soviet troop strength in Eastern Europe was not less than 175 divisions. He further claimed that most were combat ready and that quiet changes in Soviet billeting suggested they were preparing for a major mobilization.

In February 1948, the coalition Czech government failed, partly due to lack of U.S. support for President Edward Benes, a social democrat, on the grounds that he was not sufficiently anti-communist. Also in February, Gen. Stephen Chamberlin visited Clay and stressed that there were major military appropriation bills before Congress and there was a need to galvanize American support for increased military spending.

Gehlen’s estimate of 175 divisions was accepted without question. The same troops that the 1946 Army analysis described as tied down with immediate occupation and security requirements were now described by Gehlen as highly mobile. The Army’s earlier acknowledgment of Soviet troop transport and logistic problems disappeared. On Gehlen’s estimates, the Soviets were now capable of simultaneously launching large-scale offensives at Europe, the Middle East and Far East. There was no reasonable voice asking where all the required divisions or logistical support would come from. The Truman administration’s response was to stop any further cuts in military programs and to speed up the atomic weapons program. Operation Paperclip continued.

Initially, Gehlen’s information was derived from the Nazi torture and interrogations of prisoners. Some 4 million Soviet prisoners died of starvation. While Gehlen and his men may not have engaged in the executions, he was responsible for organizing the interrogations of the Soviet prisoners, which were actually a step toward liquidating thousands of them. Many were executed or simply left to starve to death.

As Gehlen’s organization grew, it began to depend on interviews with émigrés from Eastern Europe, and eventually evolved into a spy web inside the Iron Curtain. Gehlen’s reassurances to the United States that he would not employ any former SS men were promptly broken. At least a half dozen of his first staff of 50 were former SS men. Included were Hans Sommer, who torched seven Paris synagogues in 1941; Willi Kirchbaum, senior Gestapo leader for southeastern Europe; and Fritz Schmidt, former Gestapo chief of Kiel. The earliest SS recruits enlisted with phony papers and false names. It is reasonable to suspect that some American authorities were aware of the ruse.

Gehlen privately negotiated a position for Gustav Hilger with G2’s Technical Intelligence Branch in 1946. Hilger’s influence on American policy rivaled Gehlen’s. A German diplomat assigned to Russia before the war, he developed close friendships with Americans stationed in the Moscow embassy. During the war, Hilger was directly under von Ribbentrop and served as the chief political officer on the Eastern Front. He also was a liaison between Ribbentrop’s Foreign Office and the SS.

Hilger had full knowledge of the extent of the Holocaust. In December 1943, he negotiated an agreement with Italy to round up Jews into work camps. During the spring of 1944, several trainloads of Jews from these work camps were shipped to Auschwitz.

The Nazi Foreign Office also assigned Hilger to liaison with Vlasov and, by 1944, he completely integrated himself in the command structure of Vlasov’s army. At the end of the war, Hilger was officially sought as a war criminal for torture. He surrendered to U.S. forces in May 1945 and, after a brief confinement at the Mannheim POW camp, was sent to Washington for debriefing because of his expertise in Soviet affairs. Hilger was eventually given asylum in the United States under the Bloodstone project. For several years, he shuttled between Washington and West Germany, becoming an unofficial ambassador for Konrad Adenauer. Hilger was instrumental in forming the Adenauer government. Initially, Washington opposed Adenauer, but Hilger’s contacts in the State Department eventually swayed American officials to approve it in 1949.

By 1946, Gehlen resumed funding Vlasov’s army, the underground Ukrainian army and other Nazi quislings. In 1947, SS officers Franz Six and Emil Augsburg took charge of the émigré work. Both were from the Amt VI group of the SS, the combined foreign intelligence apparatus of the Nazi equivalent to the CIA. Most of Amt VI’s top officers were instrumental in the mass extermination of Jews. Augsburg escaped any prosecution. Six was a major war criminal favored by both Eichmann and Himmler. Speaking at a 1944 conference on the Jewish question, Six said: “The physical elimination of Eastern Jewry would deprive Jewry of its biological reserves. The Jewish question must be solved not only in Germany but also internationally.” Himmler was so pleased with Six’s work that he promoted him to a newly created department of his own, Amt VII.

Six eventually was betrayed, tried for war crimes, found guilty and sentenced to 20 years in prison. He only served four before John McCloy granted him clemency. Once freed, he returned to Gehlen’s organization. McCloy could hardly have been unaware of Six’s background when he granted the pardon.

In 1954, Gen. Arthur Trudeau, chief of U.S. military intelligence, received a copy of a lengthy report prepared by retired Lt. Col. Hermann Baun of Gehlen’s staff. Baun was a highly competent officer who took a dim view of the network and hated Gehlen for forcing him out of his postwar intelligence position with the West. Baun’s report listed the backgrounds of many of Gehlen’s staff members. Trudeau was so annoyed with the report he took it to Konrad Adenauer during his visit to Washington. Adenauer was deeply alarmed over the report, portions of which were leaked to the press. Through meddling by the Dulles brothers (Allen was Director of the CIA and John Foster was Secretary of State at the time), Trudeau was effectively silenced by a transfer to a remote Far East post.

Listed in Baun’s report was SS-Oberführer Willi Kirchbaum. Kirchbaum was an associate of Gestapo Chief Heinrich Müller and later the Deputy Chief of the Gestapo. He was in charge of deporting Hungarian Jews in 1944. Another was SS-Standartenführer Walter Rauff. Rauff supervised construction of the vans used on the Eastern Front to gas Jews, and was involved with SS Gen. Karl Wolff’s negotiations to surrender the German troops in Italy in 1945. After his exposure as part of the network, Gehlen transferred him to Chile, where he functioned as an agent.

SS-Sturmbannführer Alois Brunner was another member of Gehlen’s network who was a former Gestapo official working directly under Adolf Eichmann. Brunner was sentenced to death in absentia by a French court for instigating the notorious razzia carried out in France in 1942 against the Jews of Paris. Brunner was sent to Damascus as Gehlen’s resident agent and lived under various aliases. Brunner later took part in a CIA-directed program to train the security forces of Abdel Nasser. U.S. officials had to know Brunner was on the CIC’s wanted list.

One of the worst members of Gehlen’s organization was SS-Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik, who ran the Lublin camps in Poland. Before working for the United States, Globocnik worked for the British. He was also stationed in Damascus. Other members of the Gehlen organization included SS-Sturmbannführer Emil Augsberg, head of Treblinka and Belzec concentration camps; SS-Sturmbannführer Ernst Bibernstein, who commanded Einsatzkommando 6 of Einsatzgruppe C; and SS-Sturmbannführer Karl Döring, a staff member of the Dachau concentration camp. Döring was later postwar West German Ambassador to the Cameroons. SS-Standartenführer Eugen Steimle, the commanding officer of Einsatzgruppen B and later C, was convicted by an Allied court and sentenced to a long term in prison; he was released in 1951. Baun’s list included many other SS officers who served in concentration camps or were part of the Einsatzgruppen and guilty of war crimes. Most of them had little knowledge of the Soviet Union, and their use by the CIA is indefensible.

Vlasov’s Army

Vlasov’s army and émigrés from other eastern European countries were the source for Frank Wisner’s covert actions behind the rapidly developing Iron Curtain. Wisner, who believed in covert actions to eliminate communism rather than the containment policy of Kennan or Truman, recruited heavily from various émigré groups. The recruits were trained and often dropped across the borders into communist territory. Usually, Wisner’s agents met quick fates when apprehended. The thought of a spy or a mole in their organization never occurred to them, but Vlasov’s army and the Gehlen network were both infested with Soviet moles. As a result, Wisner was responsible for killing more Nazis after than during the war!

U.S. plans for a nuclear war with the USSR included integrating Vlasov’s army as part of the overall strategy. The idea of using former Nazis to conduct guerrilla warfare after dropping 60-70 atomic bombs on the USSR was first proposed in 1947 by Hoyt Vandenberg. Five wings of B29 bombers were committed to the émigré guerrilla army project. The Nazis were to be dropped inside the USSR after the bombings to gain control of strategic sites, as well as control of the local populace. Toward the end of 1948, Gen. Robert McClure won the approval of the Joint Chiefs for full-scale guerrilla warfare following a nuclear attack on the USSR. Until 1956, this was the attack plan. It employed thousands of émigrés from the USSR, including Vlasov’s army and Waffen SS men. Documents in the National Archives reference a top secret State Department plan to recruit a network of Albanian anti-communists who previously were denied visas as Nazi collaborators and war criminals.

The United States was able to equip Vlasov’s army largely with supplies from surplus war equipment. Both the CIA and the military laid claim to authority over this guerrillas force, occasionally employing them in covert operations. Such cooperation from the émigrés was later used to sanitize their records.

To hide an army of thousands in Europe, the United States simply hid them inside another army of sorts, in full view of everyone. They were hidden in labor camps known as Labor Service companies. Roughly 40,000 displaced persons were employed in these Labor Service companies, guarding POWs, removing bombing rubble from cities, locating gravesites and similar work. Officially, former Nazis were barred from these camps. But at least as early as 1946, the Labor Services recruited them. For example, Voldemars Skaistlauks, an SS general, and his top aides were part of the Latvian labor company formed on June 27, 1946. Talivaldis Karklins was another top Nazi in Madonna concentration camp. His role in torture and murders was known at least as early as 1963. He came to the United States in 1956. Finally in 1981, the office of Special Investigations - Nazi hunters in the Justice Department - succeeded in bringing charges against Karklins, resulting in a complex legal battle. He died peacefully in 1983 in Monterey, Calif.

Right-wing fears of communism backfired. The hard anti-communist faction led by Allen Dulles was the prime sponsor of the Gehlen network and Vlasov’s army in the Cold War. Since both groups were infested with Soviet moles, this led to greater Soviet penetration of U.S. intelligence and military organizations.

Project Overcast and Paperclip

On Dec. 1, 1944, OSS head Bill Donovan asked President Roosevelt if Nazi recruits could be given special privileges, including entry to the United States after the war. Roosevelt’s blunt reply:

I do not believe that we should offer any guarantees of protection in post-hostilities periods to Germans who are working for your organization. I think that carrying out of any such guarantees would be difficult and probably be widely misunderstood both in this country and aboard. We may expect that the number of Germans who are anxious to save their skins and property will rapidly increase. Among them may be some who should properly be tried for war crimes or at least arrested for active participation in Nazi activities. Even with the necessary controls you mention I am not prepared to authorize the giving of guarantees.