Just as spirits [grahan] possess [avisanti] people in ordinary life, in the same way those with attributes of the Lord possess [avisanti] those who are liberated.

—ŚIVĀGRAYOGIN in Śaivaparibhāṣā

Tantra is a category increasingly subject to debate. It is now regarded by many of the most informed scholars as a category with vague characterization and definition, an amorphous medley of practices, rites, and doctrines that became tantric by attrition; they simply do not fit elsewhere.1 This, combined with a Western fascination for things tantric (especially a mistaken identification of Tantra with sex), enables most nonspecialists to dodge the problem of Tantra. Bearing in mind this caveat, I can now undertake to unpack a knowingly (and frustratingly) incomplete inventory of possession-related practices and phenomena in mostly South Asian tantric literature. This includes, first, initiatory possession, which in many tantric texts is identified as samāveśa. This term may also designate another shadowy concept usually polluted by Western expectations, namely, enlightenment. Thus, samāveśa is not only the process of realization in tantric texts, an initial and startling possession by a deity that is invoked by the ācārya for the benefit of the disciple during a carefully orchestrated initiation, but its goal as well. In these Tantras, samāveśa is a brahmanical, body-centered, transformation (probably tantric by attrition) in which the deity to be realized is an active participant. With or without the name samāveśa, however, tantric possession may also be a kind of ritually induced oracular experience practiced by people who would never consider themselves tāntrikas. It may also indicate certain exorcistic practices that survived at the margins of Tantra (and Āyurveda).

This chapter first discusses the notion of samāveśa as it appears in the Tantras of Kashmir and northeastern India. We then turn to the phenomenon of divinization of the body, a peculiarly brahmanical practice involving the use of mantras and hand gestures (mudrā). This quasi-Vedic practice gained wide currency in a variety of Indian ritual traditions, where it was continually modified, especially, as we shall see toward the end of the chapter, in Tantric Buddhism. Another topic that must be addressed in the same context is pratiṣṭhā or prāṇapratiṣṭhā, consecration or divinization of images, the transformation of prepared (kṛtrima) stone or wooden objects into deities by investing them with eyes and breath. These discussions strongly affect our deliberations on Indic notions of selfhood and personality, which, as we have seen, bear strongly on South Asian constructions of possession. These deliberations finally lead us into an area of cultural discursivity that is often neglected in studies that are largely philological, philosophical, theoretical, and text-critical, as this one is: This is the area of artistic representation. One of the principal notions explicated here is that of multiple personality and the ease with which it is accepted in South Asia. As fully as this is represented in the ethnographic record, in an array of Sanskrit texts from the Ṛgveda to the Mahābhārata to devotional literature to the Tantras we discuss in this chapter to the ayurvedic and allied texts discussed in Chapter 12, it is perhaps nowhere better seen than in Indian art. Because the Tantric literature explicates the themes of internal spaciousness and the divinization of the body better than other genres of literature, this chapter concludes with a few examples of how this manifests in Indian art.

Along with the Vedas and the two Sanskrit epics, the Tantras provide the richest sources for the phenomenology of religious possession in premodern India, and, along with the Mahābhārata (MBh) the richest sources for its analysis. Indeed, it is evident that the Tantras, particularly those of the Śaiva and Sākta sects of Kashmir and northeastern India that developed around the turn of the first millennium C.E., confront the issue of possession and problematize it more concretely than anywhere else in Sanskrit literature. The Tantras of both the dualistic Śaiva Siddhānta and the nondualistic Trika and Pratyabhijña Śaiva sects of Kashmir address possession practically and philosophically, domesticating it ritually and conferring on it philosophical credibility, apparently sensitive to its historical prominence as a popular and legitimate mode of religious experience and expression.2 Drawing from northern and northeastern Tantras (mostly unpublished) of the eighth to twelfth centuries C.E., Alexis Sanderson describes tantric initiates, skull and trident in hand, muttering invocations

precisely where the uninitiated were in greatest danger of possession: on mountains, in caves, by rivers, in forests, at the feet of isolated trees, in deserted houses, at crossroads, in the jungle temples of the Mother-Goddesses, but above all in the cremation grounds.…[These initiates] moved from the domain of male autonomy and responsibility idealized by the Mīmāṃsakas into a visionary world of permeable consciousness dominated by the female and the theriomorphic.3

Moreover, their spiritual practices were focused intensely on the “liberating possession” of ferocious female deities acknowledged as incarnations of Śiva’s śakti.4

Assuming the centrality of a statement in a Kāpālika text, representing a Kashmiri sect of cremation ground ritual (smasāna sādhana) specialists in which possession must have been prominent (as noted by Sanderson), both the Śaiva Siddhānta (saiddhāntika) and nondual (non-saiddhāntika) Kashmiri sectarian texts turn the concept of possession around, at least philosophically.5 The non-saiddhāntika (or atimārga) Kāpālika Śaivaparibhāṣā, by Sivāgrayogin, states succinctly, “Kāpalikas attain equipoise [sāmyam, i.e.. enlightenment] through samāveśa. Just as spirits [grahāḥ] possess [āviśanti] people in ordinary life, in the same way those with attributes of the Lord [viz., Śiva] possess [āviśanti] those who are liberated.”6 This position is attacked by the saiddhāntika Śaivas because of “its dangerous resemblance to possession by evil spirits and the subject’s loss of identity and autonomy.”7 As a correction to the Kāpālika view, the Śaiva texts posit a multifaceted possession. Three facets may be identified here: first, āveśa or samāveśa as spiritual practice, from unassisted meditation to ritually assisted initiation;8 second, as a kind of special knowledge; and, third, as a state of enlightenment. Because the texts do not deal with these separately, and because they are readily evident from the discourse, it will not be necessary here to separate them as if they were distinct categories. The texts primarily consulted here are Utpaladeva’s Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā, Abhinavagupta’s two commentaries on this text, called Vimarśinī (on the text itself) and Vivṛtivimarśinī (on Utpaladeva’s lost autocommentary), Abhinavagupta’s great Tantrāloka, and Kṣemarāja’s Pratyabhijñāhṛdayam.

With respect to practice, samāveśa is identified by Abhinavagupta, in his Vimarśinī on Utpaladeva’s nondualist Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā, as abhyāsa, yogic and spiritual practice.9 Through such discipline, says Abhinavagupta, the practitioner may realize his or her identity with the Supreme Lord, even if this identity is qualified or limited by the human body, which has the capacity to realize the divine powers of the Lord only partially.10 Samāvesa is not only practice, however; it is also the goal. As Louise Finn says unambiguously, citing a commentary on the Vāmakesvara Tantra, “in Kashmir Saivism liberation is achieved not through samādhi but through samāveśa.”11 This is consistent with the general tenor of non-saiddhāntika Śaiva thought, in which mokṣa is viewed as a state of possession or samāveśa in that it is determined by levels of initiation, which are in turn verified by symptoms of śaktipāta, recognized as a variety of āvesa.12 This śaktipāta is divine energy transmitted either by one’s guru or by a siddha who, apparently, may not necessarily be one’s guru. Abhinavagupta presents a fourfold classification of siddhas: celibates (ūrdhvaretas), heroes (vira) who are on the path of Kula (kulavartman), noncelibates, and “non-physical siddhas who are non-physical gurus” (Tantrāloka [TĀ] 29.41–43).13 Jayaratha says that these disembodied gurus can enter (praveśa) the bodies of practitioners during the Kaula rite. Śaktipāta causes the initiate to become possessed (āvesa); symptoms are convulsions (ghūrṇi, kampa) and loss of consciousness (nidrā), the degree of possession revealed by their intensity (tīvra). Thence the objective was “immersion [samāveśa] into the body of consciousness; to make possession, or the eradication of individuality, permanent” (TĀ 29.207–208).

The saiddhāntika texts recognize four means of realizing samāveśa, from least effective to most: (1) āṇavopāya, corresponding to kriyā yoga with a dependence on external rituals; (2) sāktopāya, depending on the verbal practice of mantra śakti; (3) śāmbhavopāya, requiring a highly concentrated mental practice (icchā śakti) in order to merge with the absolute supreme being; and (4) anupāya, requiring no practice at all, in which merging with the absolute is achieved spontaneously, effortlessly.14

Utpaladeva asserts in his Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā (3.2.12) that true knowledge (jñana) is the primary characteristic of samāveśa. This arises when the manifestations of individuation brought on by Śiva’s projection into the individual are subordinated through appropriate yogic or spiritual practice, allowing the agency and knowledge of the conscious self to reveal themselves naturally.15 Somānanda states the goal in the opening verse of his Śivadṛṣṭi: “Let Śiva, who is realized [samāviṣṭaḥ] as our true nature, as a result of overcoming our self with his, perform obeisance to his own extended self with his innate śakti.”16 In his long commentary (Vivṛtivimarśinī) on this passage, Abhinavagupta compares and equates the present usages of samāveśa and abhyāsa17 with Bhagavadgītā 12.2,9–10, the foundational bhakti context of āvesa, in which Kṛṣṇa asserts that the best of yogins are those whose “minds are immersed in me” (mayy āveśya manaḥ) and, furthermore, that any spiritual strategy for bringing this about is acceptable. Abhinavagupta seemingly positioned himself on both sides of the debate between the saiddhāntika and non-saiddhāntika Śaivas, as he comments impartially but favorably on texts of all schools. On the one hand, his advocacy of saiddhāntika initiatory ritual (dīkṣā) in the Tantrāloka and, on the other hand, his uncompromising nondualism evidenced in his Vimarśinī, Vivṛtivimarśinī, Parātriśikālaghuvṛtti, and elsewhere point to his acceptance of samāveśa as legitimate in both conservative, brahmanical initiation and transgressive nondualistic devotional, ritual, and meditative practice. In any case, the overall context was always permeated with bhakti sentiment, and, consistent with this, Abhinavagupta offers the striking, and perhaps inevitable, statement that all acts of worship, including singing hymns of praise to the Lord, making obeisance, meditation, and pūjā, are modes of possession.18

Both of these contexts, of bhakti and abhyāsa, emphasize the ritual nature of āveśa and samāveśa, irrespective of whether the ritual is external or internal. A saiddhāntika Krama example is samāveśa within the framework of a tantric initiation consisting of the ritual construction and installation of an internal maṇḍala, the Triśūlābjamaṇḍala.19 Similarly, samāveśa or “interpenetration” of the individual with the śakti or essential energy of Śiva is one of the goals of Śaiva nondualist meditative practice. While the latter may not be as complex in its ritualization as the former, meditative practice does indeed qualify as ritual—and it always did in India, accompanied as it was by rites of purification that inevitably preceded the practice, rites demarcating psychic and physical space in preparation for full immersion into ritual liminality. One of these prerequisites or ritual framing devices generally employed in both meditative practice and in the (internal or external) construction and installation of a maṇḍala is divinization of the body through nyāsa, a mode of possession about which more is said below. For the moment, it must suffice to note a statement by Sanderson that could apply to nondualist meditative practice as well as to the saiddhāntika situation he is addressing: “That this internal worship should be preceded by the deification of the body accords with the general Tantric principle that only one who has become the deity may worship the deity.”20 The term rudraśakti-samāveśaḥ (possession by Rudra’s energy), found in Tantrāloka 30.50, indicates a permanent infusion of this highest śakti within the individual. This indicates full identification of the individual with Śiva, though Sanderson notes that this term must be understood from its appearance in the Mālinīvijayottaratantra to indicate degrees of possession attained during initiation.21

Finally, āveśa/samāveśa is itself posited as a state of liberation or, more specifically, as two such states. In the text that marks the pinnacle of his teachings on Tantra, the Tantrāloka, Abhinavagupta offers a definition of āveśa: “Āveśa is the submerging of the identity of the individual unenlightened mind and the consequent identification with the supreme Sambhu who is inseparable from the primordial Śakti.”22 Thus the tantric sense of āveśa as possession must be nuanced as “interpenetration,” as suggested above. In this way, it represents a state of enlightenment. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this definition is that it is there at all; indeed, it may be the only definition of āveśa found in Sanskrit literature. Its definition, a description of liberation according to nondualist Śaivism, reflects the discussion noted above in Utpaladeva’s Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā and Abhinavagupta’s commentaries. This discourse on āveśa is continued in discussion on the variant term samāveśa, which, as surmised, is attested much more frequently than the former in Śaiva philosophical texts.

According to the nondual Śaiva texts, samāveśa as abhyāsa or spiritual practice leads the practitioner to samāveśa as ontological state, here regarded as the “fourth state” (turyā) of the Upaniṣads. Then, through samāveśa on that initial state of liberation, one enters a state “beyond the fourth” (turyātīta). Abhinavagupta expresses this in several ways. He states in the Vivṛtivimarśinī that samāveśa indicates a complete and perfect entry into one’s own true nature.23 Thus, Abhinavagupta “understands samāveśaḥ to mean not the act of being entered but that of entering (into one’s true nature).”24 The reversal mentioned above, the reification of possession, is that samāveśa is no longer an externally induced phenomenon or experience but one that is recognized as a facet of “recognition” (pratyabhijñā) within a thoroughly (and ritually) divinized individuality. Acknowledging Abhinavagupta’s dual use of samāveśa as epistemological process and ontological state, Kaw writes: “Turyā and Turyātīta are reached by yogins only when their samāveśa becomes uninterrupted after some practice. Such yogins who attain the highest state of Samāveśa are known as Jīvan-muktas, for even in their life time, they are said to be released.”25 This movement from samāveśa as process to samāveśa as state takes one further step beyond mere jīvanmukti, however. Assuming a prior equation of samāveśa with jīvanmukti, Abhinavagupta states that the highest state of contentment (tṛptiḥ), a state of divine comportment, is to be achieved by samāveśa or meditative immersion in jīvanmukti itself.26 In other words, the higher state of samāveśa is a transformation from a state of spiritual realization, an adhyatmika state, to a divine state (vibhūtirūpā tṛptiḥ), an adhidaivika state, “where the components of limitation, including saṃskāra, are totally dissolved and incorporated into the I.”27

Finally, Abhinavagupta sums up his position and issues a warning, which I paraphrase: “When the body is filled with light and takes on the form of consciousness [saṃvidrūpam], then, as a result of further spiritual practice [abhyāsāt], all the relative projections of Śiva from the void to the corporeal body [śūnyādidehāntam] become luminous with awareness and its aesthetic flavor. Then the qualities of consciousness [saṃviddharmāḥ], empowered by the requisite śakti, rise to a divine state [vibhūtiḥ]. But in the absence of spiritual practice this āveśa is only a momentary experience. In this case the physical characteristics may be the arising of bliss, shaking, collapsing, whirling, etc.; but a state of jīvanmukti is not achieved.”28

A generation after Abhinavagupta, his student Kṣemarāja wrote a primer on the Pratyabhijñā Śaiva teachings as they were transmitted through a lineage culminating most recently with Utpaladeva and Abhinavagupta. This text, the Pratyabhijñāhṛdaya, consists of twenty sūtras and Kṣemarāja’s auto-commentary. In this text, samāveśa is elevated from a term that is used only occasionally by Utpaladeva, Abhinavagupta, and other nondualist Śaiva philosophers to one that obtains the greatest importance. In his introduction to sūtra 19, Kṣemarāja states that cidānanda, the primary characteristic of enlightenment, a state of immeasurable ecstatic bliss, is a samādhi also known by the names samāveśa and samāpatti. Samādhi and samāpatti are, of course, the principal terms used in yoga for such transformational states of mind. In spite of this stated equivalence, samāveśa is differentiated from them. It is a specific mode of merging with the Lord that assumes a process of demaniFestation or deconstruction from the orderly processes of the manifestation and construction of individuality (krama). As a mental, psychological, and physical state, samāveśa may be identical to samādhi or samāpatti (which are differentiated in yoga texts), but it is cast in terms of specific processes and a specific teleology.

In his commentary on sūtra 19, which discusses the possibility of integrating samādhi into ordinary waking state activity (vyutthāna), Kṣemarāja cites a passage from the now-missing Kramasūtras: “The aspirant whose attention is directed outward remains in samāveśa by practicing kramamudrā, the nature of which is internal directedness. Under the influence of āvesa, there occurs in this practice first an entrance [praveśaḥ] into the internal from the external, then an entrance [praveśaḥ] into the external from an internalized state. Thus, this procedure, mudrākrama, includes the dynamics of both externalization and internalization [sabāhyābhyantaraḥ].” Kṣemarāja comments that this process confers the highest śakti on the aspirant at all times through āvesa/samāveśa, which is to say through complete immersion into or possession by cit (universal consciousness). Kṣemarāja’s phrase is worth repeating: samāveśa has as its nature the unfolding of the concentrated essence of universal consciousness (cidrasa-). All of this, Kṣemarāja concludes in his twentieth and final sūtra, is tantamount to entering completely into I-ness, into a state of full self-possession, possession of one’s complete and perfect self (pūrṇāhantāveśa), a state in which one has total control over the vicissitudes of the external and internal realms, a state that is none other than Śiva.29

Michel Foucault noted that the body is the primary site of ritualization, where “the most minute and local social practices are linked up with the large-scale organization of power.”30 This is perhaps nowhere truer than in a ritual system in which the body is regarded as a receptive replicator of the cosmos. This is the case in much of Indian ritual, in which the macrocosm is classically held to naturalize, animate, and regulate, through ritual performance, the microcosmic power structures that engender and are defined by local social arrangements and practices. Such ritual is characterized by a close relationship, more precisely, a seamless flow, of body and cosmos. A well-developed strategy for burnishing this relationship is ritual divinization of the body.

One of the prominent features of religious experience as described in the Tantras, evident from the Śaiva (especially saiddhāntika) formulations of samāveśa, is the emphasis placed on the body, especially during initiation. The body is “immortalized” through the grace or revelation of Śakti in her jñāna (knowledge) aspect. One may be liberated not only while in the body, but through the body as well.31 The deity manifests within the body; indeed, it manifests as the body. This requires śaktipāta, described as a violent “descent” (pāta) upon the initiate, an immersion or possession (āvesa) of the initiate’s body and self by the śakti,32 which may be thought of as “power,” “grace,” and “cosmic (feminine) energy” together.33 The symptoms of śaktipāta resemble those of possession as described in ethnographic reports, for example, exhibitions of blissfulness, shaking, staggering, whirling, or falling on the ground unconscious.34 For example, Sax’s informants in Garhwal report that “the innermost self shakes” during possession.35 Diemberger reports that Tibetan female oracles have this sort of characteristic experience after having their “energy-channels” opened by a lama. She writes: “The god, in fact, is said to enter the body along the energy-channels and if these are not purified, the person may be affected by a variety of mental and physical illnesses. Uncontrolled visions, voices, fainting, weakness, and the experience of a death-like state are the most common symptoms.”36 There appears to be tantric influence in these initiatory experiences. The Vijñānabhairava (verse 69) also describes the entry of or possession by śakti (śaktyāvesa) in terms of sexual absorption, the man immersed not just in the śakti as the spiritual energy of the Goddess, but as real, live, full-bodied woman. This is compared to absorption in the bliss of brahman, which is then said to be the bliss of one’s own self.

References to āvesavidhi (injunctions intended to bring about ritual possession) may be found in saiddhāntika Śaiva Tantras. Among these saiddhāntika texts are the Yoginītantras (employed by Sanderson) in which one of the features of an elaborate abhiṣeka (ritual of empowerment) is the leading of blindfolded male initiates by female adepts (yoginī) or male assistants (karmavajrin) to the edge of a maṇḍala inscribed on the floor or ground. The initiates, writes Sanderson, “are made to take an oath of absolute secrecy (koṣapāna) and are then made by means of mantras to become possessed by the maṇḍala-deities (āveśavidhi).”37 This sort of divinizing of the body is wholesale: The divinity or divinities are seen as discrete and identifiable entities generated from without, and with the power to possess if only the connection is properly forged.

Nyāsa

Two phenomena that share conceptual territory with āveśa are nyāsa and (prāṇa-) pratiṣṭhā. There is an important distinction between them: The latter two are intentional, textualized, and enjoined bodily constructions, transformations of intellectual and social practices (arguably these are the same thing) into sacred physical terrain. Nyasa (literally “setting upon, placing down, imposition”)38 is a common, and often standard, part of brahmanical worship that finds its greatest advocacy in the Tantras and Purāṇas. As a result, extended instruction of nyāsa may be found in virtually every manual of Hindu daily practice, including those sold outside the gates of Hindu temples everywhere in India.39 Nyasa is employed in obligatory rites (nitya) such as the daily saṃdhyā, the twice-daily rites of the twice-born performed at sunrise and sunset, as well as in the full range of rituals to be performed on special occasions, some calibrated calendrically (naimittika), and others performed to fulfill personal desires (kamya).40 Related to mudras or hand positions of esoteric significance (cf. Tantraraja Tantra 4.44d, which explicitly links a certain mudra with āveśa),41 nyāsa is a practice that combines simple mudras with brief mantras invoking names of deities, divine powers, ṛṣis, Vedic sacrifices, or letters of the alphabet. The intent of nyāsa is to impose or place the power of the mantras, and perforce the deities, and so on, which they inscribe, on or within various body parts, either one’s own or that of an image of a deity. This is effected, according to the widespread theology of nyasa, through a process called bhūtasuddhi, purification of the five fundamental elements (mahabhūtas)—earth, water, fire, mobile air, and all-pervasive space.42 The idea of a conjunction of deity and ritualist is old in India. The Bṛhaddevatā, a text of probably the mid-first millennium C.E. that organized Vedic knowledge according to the deities of the Ṛgveda, states as part of its conclusions that “fully introducing the deity into the mind” (manasi saṃnyasya devatām) while performing a sacrifice is a true signifier of knowledge.43

Abhinavagupta and Kṣemarāja describe mudra as both an instrument of āveśa and a state of possession itself. Gavin Flood explicates this: “To say that mudrā is a way of accessing higher layers of the cosmos means that individual consciousness is absorbed into or possessed (āveśa) by mudrā, or that the individual body absorbs mudrā into itself. The PTLV [Parātriṃsikālaghuvṛtti] says that one’s own body becomes possessed (āvesa) by mudrā and mantra, which can be read as, becomes a channel for, higher cosmic powers which erode the sense of individuality and distinction.”44 This agrees with the idiomatic use of āveśa and samāveśa elsewhere in the Kashmiri Śaiva and Sākta literature. Furthermore, say these philosophers, the body can become a bridge to these “higher cosmic powers” not just through mudrā but through āsana, the practice of yoga, presumably indicating variations on the teachings of Patañjali and other advocates of classical yoga.45 Āsana, they claim, is the yogic equivalent of bhūtaśuddhi, described above as the essence of nyāsa. “Both represent the destruction or purification of the gross individual body, in order that a divine body can be created.”46

Āsana, says Kṣemarāja, is not simply posture but the power (bala) of the supreme śakti.47 As such, it is the original and final agent of transformation. It follows, then, as Abhinavagupta states, that mudrā is also an exercise of power, bestowed in initiation.48 Kṣemarāja reinforces this, stating that all the actions of an awakened one (buddha) are in fact mudrā. In the Pratyabhijñāhṛdaya, he quotes the Kramasūtras, “which define this mudrā as the interpenetration of the inner and the outer due to the force of possession (āveśavaśāt); the entrance (praveśa) of consciousness from the external to the internal (antaḥ) and from the internal to the external.”49 Mudrā, āsana, and nyāsa, then, are not mere gestures or movements; they are nuances, signifiers, or resonances of āvesa, thus āveśa itself. In the same way, they are emblematic of an empirical, even scientific, paradigm in which spirit (śakti) or, more amorphously and less specifically, consciousness (cit), transmutes into power, pattern, and matter. As matter, they qualify as substance codes, in Marriott’s terminology. They operate through an alchemical process, replicating the process of symbolic and material creation (e.g., vegetable matter > coal > diamond, solar energy > potable gold), employing śakti as a beginning as well as an ending point.

Another phenomenon treated in the same conceptual terms as nyāsa and mudrā, being at once parts and the whole of āvesa, as well as its process, is orgasm (kampakāla). These four are viewed as the culmination of an organically fruitful act that replicates and “imposes” cosmic processes. According to Somānanda, orgasm reflects and recapitulates the ānanda (bliss) and camatkāra (astonishment) of Paramaśiva and thus, in the right perspective, can be a kind of realization. According to Somānanda, “pure consciousness is perceived in the heart when semen is discharged (visargaprasara).”50 The Vijñānabhairava states that “possession by Śakti or absorption in her—the term āveśa is ambiguous—occurs during the (sexual) excitement of uniting with Śakti (śaktisaṃgamasaṃkṣubdha).”51

As a process, nyāsa and mudrā are intended both to mirror and replicate the constitution of the original cosmic “person” as expressed in the Puruṣasūkta (Ṛgveda [ṚV] 10.90) and, in more extended fashion, in Purāṇic deities like Varāha, who is described at great length as Yajñavarāha, “Varāha as the embodiment of the sacrifice,” Varāha whose very body is composed of the spectrum of sacrifices.52 Both nyāsa as a practice and Yajñavarāha as a cosmic image represent an extension of the theme of a composite body and self noted earlier in examples from the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa and other vedic texts. It is important here to remember that in the Indian concept of possession, identity is not closed or limited by name or definition, but is open, flexible, and integrative. Nyāsa is all of these in both the construction and embodiment of the deity, ṛṣi, or other structure imposed on the ritualist.

Nyāsa mirrors and reconstructs an original or archetypal Puruṣa as well as later composite deities such as Yajñavarāha in that it is a process of resorption rather than emanation of the constituent units of the cosmos. It is an absorption into oneself, into one’s body and being or, in the case of (prāṇa)pratiṣṭhā, into the embodied form of the deity. The cosmic Puruṣa and Yajñavarāha not only emanate and disseminate the parts of the cosmos from their bodies, but embody these parts as their physical essence, a condition that is replicated in nyāsa. In this sense, nyāsa may be viewed as a simplified and dramatic reduction of the agnicayana, where the parts of the cosmos are reassembled in the form of the bird-shaped fire altar. This reassembled organic whole is regarded as nothing less than the creator god Prajāpati himself, who contains within him the entire cosmos. Both the agnicayana and nyāsa, then, become strategies for effecting “natural circulation,” though in these instances it is not essences or abstractions such as medhas (cf. Chapter 5) that are transferred or circulated, but actual cosmic (and social) structures that are collected into various patterns and energized, to be taken up anew by Prajāpati or any other deity (such as Kṛṣṇa or Śiva) and dispersed throughout the cosmos. In practice, nyāsa is envisioned as a procedure for consecration or enlivenment, performed in order to empower, sanctify, and protect the individual, the body (part), or the iconic form of a deity, all of which must be rendered pure for ritual and other spiritual activity. And what better for accomplishing this than (ritual) introduction of sacred elements into the body (or image) itself?

The Bhāgavata Purāṇa (BhP) provides an excellent example of nyāsa, along with compelling reasons why it should be practiced. BhP 6.8 provides the text of a Nārāyaṇa kavaca, or ritual construction of “armor” (kavaca), which enables the devotee to obtain the protection of Viṣṇu, here called Nārāyaṇa. The kavaca consists of nyāsa followed by a long hymn appealing to Viṣṇu and his many incarnations, body parts, and weapons (e.g., discus, mace, conch), for protection. The BhP (6.8.4–11) states that the nyāsa should be performed with “speech controlled” (vāgyataḥ), meaning that the mantras should be muttered inaudibly or recited silently. “One should equip or harness oneself with a protective covering fashioned from Nārāyaṇa”53 by placing different syllables of various mantras (e.g., om namo nārāyaṇāya, om namo bhagavate vāsudevāya) on parts of the body, hands, joints of the fingers, heart, and crown of the head. Finally, the devotee should complete the transformation by visualizing him or herself as the Supreme Self in the form of the embodied Lord manifest as knowledge, splendor, and ascetic heat, and possessed of the six divine virtues (power, beauty, fame, wealth, wisdom, and dispassion). In this condition, one should then recite the hymn (BhP 6.8.11). In addition, Vaiṣṇavas in practice inscribe tilakas or sectarian marks with white sandalwood powder (gopīcandana) on twelve different parts of the body, each one accompanied by the recitation of one of the twelve principal names of Kṛṣṇa. This is for the purpose of forming the image of Kṛṣṇa on and in one’s body.

Another extended example of nyāsa demonstrates the manner in which brahmanical thought constructed a “self,” an entity close to a “person,” through an accumulation of powers that are conferred a nondual or advaitic trajectory as they accumulate. The text is a quasi-vedic series of brief mantras, some of which bear vedic accentuation, which occurs as part of the introductory apparatus to the recitation of the Rudrādhyāya, the “Chapter on Rudra” from the Taittirīya Saṃhitā (TS, 4.5.1–11). This introduction, including the nyāsa, is an invention of post-vedic ritualists who recognized that the Rudrādhyāya, the most revered of all recited passages from the TS, had acquired a special sanctity and therefore deserved its own ritual apparatus. Although the Rudrādhyāya was initially prescribed for recitation during the agnicayana,54 the content of the text suggests that it likely stood on its own as an early recitational passage.55 As an independent text, it is today (as has likely been for thousands of years) recited in a large number of semi-vedic, which is to say Purāṇic and Agamic, rites practically in an ad hoc fashion. As such, the recitational ritual has grown around it. The text of the Rudrādhyāya from the TS is enveloped in a classic ritual framework in which it is conferred a liminal existence, following Victor Turner’s notion of framing liminality.56 During the initial part, the rite of entering that liminal, timeless, space during which the text is recited, the ritualist, who is assumed to be a brahmanical follower of one of the half-dozen ritual sākhās or branches of the TS,57 recites this nyāsa and “intends” it on his body. After entering into this mantrically instigated state of divine personhood, the ritualist then recites the text of the Rudrādhyāya. The following account of this is taken from a popular handbook published by the Ramakrishna Mission called Mantrapuṣpam.58

After enjoining the ritualist to bathe and perform appropriate purification, to keep the senses under control and observe celibacy, to wear white garments and face the deity, he should establish the deities in his body (ātmani). The text continues:

prajanane brahmā tiṣṭhatu | pādayor viṣṇus tiṣṭhatu | hastayor haras tiṣṭhatu | bāhvor indras tiṣṭhatu | jaṭhare ’gnis tiṣṭhatu | hṛdaye śivas tiṣṭhatu | kaṇṭhe vasavas tiṣṭhantu | vaktre sarasvatī tiṣṭhatu | nāsikayor vāyus tiṣṭhatu | nayanayoś candrādityau tiṣṭhetām | karṇayos aśvinau tiṣṭhetām | lalāṭe rudrās tiṣṭhatu | mūrdhnādityās tiṣṭ.hantu | śirasi mahādevas tiṣṭhatu | pṛṣṭhe pinākī tiṣṭhatu | purataḥ śūlī tiṣṭhatu | pārśvayoḥ śīvāśaṅkarau tiṣṭhetāṃ | sarvato vāyus tiṣṭhatu | tato bahiḥ sarvato ’gnir jvālāmālāparivṛtas tiṣṭhatu | sarveṣv aṅgeṣu sarvā devatā yathāsnānaṃ tiṣṭhantu | māṃ rakṣantu ||

May Brahmā be established in [my] organ of generation. May Viṣṇu be established in [my] feet. May Hara be established in [my] hands. May Indra be established in [my] arms. May Agni be established in [my] belly. May Śiva be established in [my] heart. May the Vasus be established in [my] throat. May Sarasvatī be established in [my] mouth [organ of speech]. May Vāyu be established in [my] nostrils. May the Sun and the Moon be established in [my] eyes. May the two Aśvins be established in [my] ears. May Rudra be established on [my] forehead [lalāṭa]. May Āditya be established on the front of [my] head [mūrdhan]. May Mahādeva be established on [my] head [siras]. May Vāmadeva be established on the crown of [my] head. May the Staff-Bearer [pinākin] be established on [my] back. May the Bearer of the Trident [śūlin] be established on [my] chest. May Śiva and Śaṅkara be established on [my] flanks. May Vāyu be established everywhere. Finally, may Agni be established everywhere outside [me], surrounding [me] like a garland of flames. May all the Gods [devatāḥ] establish their respective places in all [my] limbs. May they protect me!

agnír me vācí śritáḥ | v g gh

g gh daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | vāyúr me prāṇé śritáḥ prāṇó h

taṃ bráhmaṇi | vāyúr me prāṇé śritáḥ prāṇó h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | s

taṃ bráhmaṇi | s ryo me cákṣuṣi śritáḥ | cákṣur h

ryo me cákṣuṣi śritáḥ | cákṣur h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | candrámā me mánasi śritáḥ | máno h

taṃ bráhmaṇi | candrámā me mánasi śritáḥ | máno h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | díśo me śrótre śritáḥ | śrótraṃ h

taṃ bráhmaṇi | díśo me śrótre śritáḥ | śrótraṃ h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi |

taṃ bráhmaṇi |  po me rétasi śritáḥ | réto h

po me rétasi śritáḥ | réto h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | pṛthivī me śárīre śritáḥ | śárīraṃ h

taṃ bráhmaṇi | pṛthivī me śárīre śritáḥ | śárīraṃ h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | óṣadhivanaspatáyo me lómasu śritáḥ | lómāni h

taṃ bráhmaṇi | óṣadhivanaspatáyo me lómasu śritáḥ | lómāni h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | índro me bále śritáḥ | bálaṃ h

taṃ bráhmaṇi | índro me bále śritáḥ | bálaṃ h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | parjányo me mūrdhní śritáḥ | mūrdh

taṃ bráhmaṇi | parjányo me mūrdhní śritáḥ | mūrdh h

h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | īśāno me manyáu śritáḥ | manyúr h

taṃ bráhmaṇi | īśāno me manyáu śritáḥ | manyúr h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | ātm

taṃ bráhmaṇi | ātm me ātmáni śritáḥ | ātm

me ātmáni śritáḥ | ātm h

h daye | h

daye | h dayaṃ máyi | ahám am

dayaṃ máyi | ahám am te | am

te | am taṃ bráhmaṇi | púnar ma ātm

taṃ bráhmaṇi | púnar ma ātm púnar

púnar  yur

yur  gāt | púnaḥ prāṇáḥ púnar

gāt | púnaḥ prāṇáḥ púnar  kūtam

kūtam  gāt vaiśvānaró raśmíbhir vāvṛdhānáḥ | antás tiṣṭhatv am

gāt vaiśvānaró raśmíbhir vāvṛdhānáḥ | antás tiṣṭhatv am tasya gop

tasya gop ḥ ||

ḥ ||

Agni abides in my speech. My speech abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Vāyu abides in the lifebreath. My lifebreath abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Sūrya abides in my eye. My eye abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. The moon abides in my mind. My mind abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. The directions abide in my ear. My ear abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Water abides in my semen. My semen abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. The earth resides in my body [śárīra]. My body abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Cultivated and wild plants abide in my hair. My hair abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Indra abides in my strength. My strength abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Parjanya abides on the front of my head. The front of the head abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Isāna abides in my passion [manyu]. My passion abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. The self [ātmán] abides in my ātman. My ātman abides in my heart. My heart abides in me. I abide in immortality. Immortality abides in bráhman. Again, may my ātmán come to me for another lifespan [púnar  yuḥ]. Again, let my lifebreath come to another desire [púnar

yuḥ]. Again, let my lifebreath come to another desire [púnar  kūtam] and let that Agni common to all [vaisvānará] choose me with his rays of light [raśmí]. Let the final limit of immortality be established as my protector.

kūtam] and let that Agni common to all [vaisvānará] choose me with his rays of light [raśmí]. Let the final limit of immortality be established as my protector.

asya śrīrudrādhyāyapraśnamahāmantrasya aghora ṛṣiḥ anuṣṭupchandaḥ saṃkarṣaṇamūrtisvarūpo yo ’sāv ādityaḥ paramapuruṣaḥ sa eṣa rudro devatā | naman śivāyeti bījam | śivatarāyeti śaktin | mahādevāyeti kīlakam | śrīsāmbasadāśivaprasādasiddhyarthe jape viniyogaḥ ||

Aghora is the seer of the great mantra that constitutes this chapter called the Illustrious Rudrādhyāya. The meter is anuṣṭubh.59 The deity is Rudra, the Supreme Being [paramapuruṣaḥ] who is the same as yonder Sun, whose natural embodiment is that of Saṃkarṣaṇa. The seed mantra is namaḥ śivāya [“Obeisance to Śiva”]. The śakti mantra is [namaḥ] sivatarāya [“Obeisance to the Greater Śiva”]. The kīlaka mantra60 is [namo] mahādevāya [“Obeisance to Mahādeva”]. When the goal of repeating [the Rudrādhyāya] is to obtain the grace of Sāmbasadāsiva, [this is the] ritual procedure [to be followed].

oṃ agnihotrātmane aṇguṣṭhābhyāṃ namaḥ | darśapūrṇamāsātmane tarjanībhyāṃ namaḥ | cāturmāsyātmane madhyamābhyāṃ namaḥ | nirūḍhapaśuban dhātmane anāmikābhyāṃ namaḥ | jyotiṣṭo mātmane kaniṣṭhikābhyām namaḥ | sarvakratvātmane karatalakarapṛṣṭhābhyāṃ namaḥ | agnihotrātmane hṛdayāya namaḥ | darśapūrṇamāsā tmane śirasi svāhā | cāturmāsyātmane śīkhāyai vaṣaṭ | nirūḍhapaśubandhātmane kavacāya huṃ | jyotiṣṭhomāt mane netratrayāya vauṣaṭ | sarvakratvātmane astrāya phaṭ | bhur bhuvas suvar om iti digbandhaḥ |

Om! Obeisance to the two thumbs, which have as their nature the agnihotra. Obeisance to the index fingers, which have as their nature the darśapūrṇamāsau. Obeisance to the middle fingers, which have as their nature the cāturmāsyas. Obeisance to the ring fingers, which have as their nature the nirūḍhapaśubandha. Obeisance to the little fingers, which have as their nature the jyotiṣṭoma. Obeisance to the palms and the backs of the hands, which have as their nature all the sacrifices. Obeisance to the heart, which has as its nature the agnihotra. Obeisance to the head, which has as its nature the darśapūrṇamāsau. Obeisance to the crown of the head, which has as its nature the cāturmāsyas. Obeisance to the aura,61 which has as its nature the nirūḍhapaśubandha. Obeisance to the third eye, which has as its nature the jyotiṣṭoma. Obeisance to the astral weapon, which has as its nature all the sacrifices. Phaṭ! Thus, the syllables bhuḥ, bhuvaḥ, suvaḥ, and om are fixed in the [four] directions.

It is important to read this in full, to translate this simple passage replete with redundancies, because the cadence of the text, its simplicity and comprehensibility, its organization and teleology, are reminiscent of drum rolls and chants of shamanic ritual.62 These are the cadences of possession, even as it is Sanskritized and brahmanized. Nyāsa, we can say, is brahmanical possession. It is a re-anatomization within an individual of the dismembered Puruṣa. The performer, a ritualist familiar with the cadences of Sanskrit, is not just reciting a text and connecting the dots between mantras and body parts—he (usually he) is training and prompting his body to resonate with the cadences of the text. These cadences, in Foucault’s words, embed “minute and local social practices” that wield and articulate cultural and, eventually, political power. In addition to the minimal speech-act of recitation, hence re-creation, the ritualist employs various mudrās regularly during the course of the recitation. Holding these mudrās, he touches the respective body part into which the deity is said to enter, with his right (or if necessary his left) hand. Thus, this performance of the Rudrādhyāya is physically engaged, not merely recited. Ritually, which is to say intentionally and therefore not meaninglessly, the reciter adopts the persona of the gods as he recites the text. As he invests his body with divinity, he confers on himself the power and authority with which the performance becomes effective. The brahman ritualist who recites the Rudrādhyāya in this context does not experience deity possession in the same manner as does a devotee at the temple of Khaṇḍobā in Jejuri on the new moon day that falls on a Monday (somavatī amāvāsyā).63 Nor will he experience the devotionally driven āveśa of a devotee performing sevā on his or her beloved deity, or the possession that Śaṅkara experienced upon entering the body of the dead king Amaruka. But there can be little doubt that the ritual is designed to reorient the ritualist toward a divine realm that is the product of millennia of brahmanical tinkering. This tinkering, which has a track record of success, at least in the minds and hearts of the ritualists, is in fact tinkering with practices of power. These practices are acts of purification, isolation, and proprietary possession of divinity, facets of brahmanization that are discussed elsewhere and need not detain us here.

Two further matters must be mentioned here. First, this possession, as I designate it, is described without the use of the primary critical vocabulary discussed here, derivatives of ā/pra-√viś or √gṛh. Instead, the verbs √sthā (tiṣṭhatu, etc.) (to establish, stand) and √śri (śritaḥ) (abide in, cling to, take possession of) establish both the motion and the contiguity that characterize āvesa, praveśa, and so on, and are nearly synonymous with them in expressing an appropriate entrance or pervasion. The root √sthā (tiṣṭhatu, etc.) is employed to express the occupation of deities on or in body parts. These deities are Brahmā, Viṣṇu, Hara, Agni, Śiva, the Vasus, Sarasvatī, Vāyu, Sun, Moon, the Aśvins, Rudra, Āditya, Mahādeva, Vāmadeva, Pīnākin, Śūlin, Śiva, and Śaṅkara, and finally all the gods together (sarvā devatā). Just as appropriately, √śri (śritaḥ) provides the sense of pervasion for natural forces, including fire, wind, sun (these three are the representatives of Agni on the terrestrial plane, the mid-region, and the celestium), the moon, the directions, water, earth, wild and domestic plants, Indra, Parjanya (Rain), Īśāna (one of the eleven Rudras, Śiva as the sun), and the self (ātmán). Thus, forms of these two verbs are used to express different aspects of what may be expressed broadly as possession.

Second, to return to an earlier point, the entire passage reflects a late first- and early second-millennium C.E. brahmanical strategy of advaitic reinscription that homogenizes the earlier, much more diverse but by now superannuated, vedic ritual theology. Although the phenomenon of identifying one entity, idea, or object with another—not randomly but as a “code of connections”64—has long been noticed in vedic and succeeding brahmanical thought, here is a text (and I could easily locate dozens of similar ones) that is engineered to reconstruct personal identity through acts of self-identification with deities and vedic sacrifices while simultaneously subordinating each identification to an absolute bráhman. In the key second section of the passage translated, Agni is said to abide in speech, speech in the heart, the heart in the “me” of the ritualist, that “me” in the immortal, and finally the immortal in bráhman. Thus commences a strategy of “practical Vedānta”65 designed to compel the ritualist to realize the identity of a deity with a body part, then with the individual self, and finally with bráhman. In this ritual exercise, the individual’s body parts, heart, and self are so fully identified with specific deities that it must fall within the range of deity possession, though that possession is ultimately nullified and transcended by a final identification with the absolute brahman.

Regardless of the perfunctory manner in which this is ordinarily performed (doubtless a consequence of text-based performance), a transformation in perception is assumed to occur. At the very least, this transformation is a result of a mantra-induced realization of a pre-existing condition, a transformation of quality, or a transfer of essence, at most through a more substantial infusion of the very deity, ṛṣi, and so forth, into the body or image. This infusion, clearly, is reminiscent of certain aspects of āveśa: it is envisioned, intended, and set in motion by the practitioner, and it is an immersion of distinctly positive forces into oneself or an image of one’s deity. In short, deities, powers, and so on are invited to take possession of the body. But they are invited in a brahmanically programmatic, that is, “textual,” way, one that emphasizes purity at the expense of spontaneity and danger. It is likely that the introduction of nyāsa into standard brahmanical ritual represented a domestication of certain tantric (or vedic) initiatory processes or even those of popular religious possession. Through exercising programmatic control, which occurred as a result of the elimination of its unstructured, noninstitutionalized, unpredictable, and (thus) frightening aspects, possession was drained of its spontaneity. It became vidhi (ritual prescription), which denied to it experiential possibilities beyond text, by rendering it representational in the sensibilities of the ritualist, rather than actual. This is not, however, to say that, as a general rule, confinement of possession within ritual boundaries necessarily reduced its experiential potency. Indeed, for many, particularly among non-brahmanized sects, such confinement served to confer acceptable social dimensions upon it, thus legitimizing it as a viable form of religious expression, as ethnographic work has decisively shown. Examples of the successful ritual demarcation of the unpredictable can be readily seen among the devotees of Khaṇḍobā at Jejuri or in dramatic performance such as Terukkūttu or Teyyam.

One further example of nyāsa should be discussed. This may be seen in the fourth chapter (ullāsaḥ) of the Kulārṇavatantra (KAT). The author of this well-known text of the Kaula tradition of Śaiva ritual, written sometime in the first centuries of the second millennium C.E., is unknown, but, according to the colophon at the end of the first ullāsa, the text is supposed to be the fifth section (khaṇḍa) of the Urdhvāmnāyatantra, a text now lost, but said (surely symbolically) to have consisted of 125,000 verses. Such statements aside, the fourth ullāsa consists of instructions for two progressions of nyāsa, one called “small” (alpaṣōḍhā, 4.17–18), the other “great” (mahāṣoḍhā, 4.19–130). Strikingly, the KAT states that the mahāṣoḍhānyāsa, which is indeed quite intricate, is for the purpose of devatābhāvasiddhi or perfection of the psychophysical experience (bhāva) of the deity (4.19), in this case Śiva. We have seen above that in bhakti texts the term bhāva is tantamount to āvesa; thus here the KAT can mean only that the aspirant transforms every aspect of his being (usually a male is presumed) into that of Śiva. This is nothing less than possession, as discussed above. In a verse at the end of this ullāsa (4.128), Īśvara or Śiva, who reveals this secret, reinforces the importance of this nyāsa to the goddess, his dialogical partner: “One who practices this nyāsa obtains ājñāsiddhi [the power to assure that whatever one orders is carried out]. In the world there is no protection greater than this, the bestower of the siddhi of devatābhāva. This, no doubt is the truth, it is the truth, O Fair-faced One.”

The nyāsas in this ullāsa are sixfold and construct—or reveal—systematic links between mantras, deities, body parts, and elements of the cosmos. These identifications disclose a transformation of the aspirant, his devatābhāva, brought on through a code of connections that harks back to the vedic Brāhmaṇa and Āraṇyaka texts for their authority. The first is called prapañca-nyāsa (the nyāsa of manifest creation). This consists of three parts. In the first, the aspirant links a string of bija mantras, Sanskrit vowels, sixteen names of the goddess Lakṣmī, body parts, and geographical forms, and at the end the same bija mantras in reverse order. For example, the first two to be recited are: au ai

ai hrī

hrī śrī

śrī hsau

hsau a

a prapañca rūpāyai śrīyai namaḥ śirasi s-hau

prapañca rūpāyai śrīyai namaḥ śirasi s-hau śrī

śrī hrī

hrī ai

ai au

au , meaning “au

, meaning “au ai

ai hrī

hrī śrī

śrī hsau

hsau a

a obeisance to Śrī on the head in the form of the manifest universe s-hau

obeisance to Śrī on the head in the form of the manifest universe s-hau śrī

śrī hrī

hrī ai

ai au

au ”; then au

”; then au ai

ai hrī

hrī śrī

śrī hsau

hsau ām dvīparūpāyai māyāyai namaḥ mukhavṛtte s-hau

ām dvīparūpāyai māyāyai namaḥ mukhavṛtte s-hau śrī

śrī hrī

hrī ai

ai au

au , meaning “au

, meaning “au ai

ai hrī

hrī śrī

śrī hsau

hsau ā

ā obeisance to Māyā on the face in the form of a continent s-hau

obeisance to Māyā on the face in the form of a continent s-hau śri

śri hrī

hrī ai

ai au

au .” The remaining loci are: ocean (jaladhi), mountain (giri), town (pattana), ritual altar (pīṭha), field (kṣetra), forest (vana), religious refuge (asrama), cave (guha), river (nadī), crossroad (catvara), the domain of “sprout-born” entities (udbhidja, viz. plants), the domain of “sweat-born” creatures (svedaja, viz. mosquitoes, insects, etc.), the domain of egg-born beings (aṇḍaja, viz. birds), and the domain of “embryo-born” creatures (jarayuja, viz. mammals and higher primates). In this way, the aspirant realizes the entire physical universe within him. The second part of the prapañca-nyāsa does the same for units of time, from the smallest, the lava (tiniest fraction of a second), to the largest, the pralaya (period of cosmic dissolution), identifying these with manifestations of the goddess Kālī. The third links the ten manifestations of Sarasvatī with various aspects of the functioning being. These are the five fundamental elements (pañcabhūta) linked with Brāhmī; the five senses (tanmatra) linked with Vāgīśvarī; the five organs of action (karmendriya) with Vāṇi; the five sense organs (jñanendriya) with Sāvitrī, the five principal prāṇas with Sarasvatī; the three guṇas with Gāyatrī; the fourfold inner sense organ (antaḥkaraṇa) consisting of mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi), ego (ahaṃkāra), and consciousness (citta) with Vākpradā; the four states of awareness (waking, dreaming, deep sleep, and turiya, the “fourth” or transcendental state) with Saradā; the seven bodily constituents (skin, blood, flesh, fluid, marrow, bone, and semen) with Bhāratī; and the three bodily humors (doṣa: vāta, wind; pitta, bile; and kapha, phlegm) with Vidyātmika. Thus, through the prapañca-nyāsa, space, time, and human function are appropriated, experienced, and transformed within the body of the individual.

.” The remaining loci are: ocean (jaladhi), mountain (giri), town (pattana), ritual altar (pīṭha), field (kṣetra), forest (vana), religious refuge (asrama), cave (guha), river (nadī), crossroad (catvara), the domain of “sprout-born” entities (udbhidja, viz. plants), the domain of “sweat-born” creatures (svedaja, viz. mosquitoes, insects, etc.), the domain of egg-born beings (aṇḍaja, viz. birds), and the domain of “embryo-born” creatures (jarayuja, viz. mammals and higher primates). In this way, the aspirant realizes the entire physical universe within him. The second part of the prapañca-nyāsa does the same for units of time, from the smallest, the lava (tiniest fraction of a second), to the largest, the pralaya (period of cosmic dissolution), identifying these with manifestations of the goddess Kālī. The third links the ten manifestations of Sarasvatī with various aspects of the functioning being. These are the five fundamental elements (pañcabhūta) linked with Brāhmī; the five senses (tanmatra) linked with Vāgīśvarī; the five organs of action (karmendriya) with Vāṇi; the five sense organs (jñanendriya) with Sāvitrī, the five principal prāṇas with Sarasvatī; the three guṇas with Gāyatrī; the fourfold inner sense organ (antaḥkaraṇa) consisting of mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi), ego (ahaṃkāra), and consciousness (citta) with Vākpradā; the four states of awareness (waking, dreaming, deep sleep, and turiya, the “fourth” or transcendental state) with Saradā; the seven bodily constituents (skin, blood, flesh, fluid, marrow, bone, and semen) with Bhāratī; and the three bodily humors (doṣa: vāta, wind; pitta, bile; and kapha, phlegm) with Vidyātmika. Thus, through the prapañca-nyāsa, space, time, and human function are appropriated, experienced, and transformed within the body of the individual.

The remaining sections of the sixfold nyāsa are the bhuvana-nyasa, in which different divine Śaktis and their entourages of hundreds of millions of yoginīs are identified on the body with the fourteen planes of the universe, employing the same bija mantras and formulaic pattern as used above. In the murti-nyasa, the aspirant places on his body the sixteen forms of Viṣṇu and their corresponding śaktis, the twelve manifestations of Śiva and their śaktis, and the ten forms of Brahmā and their śaktis. Then follows mantranyāsa, in which billions of two-lettered mantras, three-lettered mantras, and so on ascending up to sixteen-lettered mantras are placed symbolically by their goddesses on ascending parts of the ritualist’s body. Then comes devata-nyasa, in which various goddesses and their respective legions of thousands of realized beings, celestial beings, and male deities are imposed on various body parts. Finally, in mātṛkā-nyāsa the aspirant places different “Mother Goddesses” (mātṛkā) along with myriad tens of millions (anantakoṭi) of members of the families of the Bhairava form of Śiva, including negatively charged beings (bhūta, preta, piśāca, etc.) and other denizens of the universe under their authority, on ascending body parts and energy centers. In sum, says Śiva himself in the KAT (4.119), “When nyāsa is performed in this way, O Goddess, the mantrin who is patient in times of both contraction and grace without doubt becomes a direct manifestation of the highest Śiva.”

In this way the individual, rather than retreating into a kind of advaitic oneness, expands into one. The process is, literally, one of taking possession of, arranging, and integrating the constituent parts of this world, the cosmic realms, all earthly and divine beings, and the functions of manifestation. The nature of life as a practical reality requires that the individual protect him or herself in infinite ways from the responsibility and awesomeness of the universe (cf. Arjuna in the eleventh chapter of the Bhagavadgītā). This shield—culturally, individually, or otherwise configured—enables that person to construct and conduct a manageable definition of his or her own individuality. Nyāsa, when used as part of an initiatory apparatus, as it is in Tantra, becomes an instrument for effacing that safe definition and emerging as a complex multiform personality that assumes divine and incomprehensible proportion; indeed, it is so awesome that it forces the individual to reconsider selfhood.

Pratiṣṭhā

Related to nyāsa are pratiṣṭhā (establishment of a deity in a material object), attested as early as the vedic Brāhmaṇa literature and, more specifically and recently, praṇa-pratiṣṭhā (installation of vital breath [prāṇa] into an image of a deity).66 The relatively recent Tantrarāja Tantra (2.39–40) notes the possible loci of pratiṣṭhā in the case of the goddess: She can be established in a cakra (viz. a yantra), a disciple, or a fashioned image of herself. Pratiṣṭhā and prāṇapratiṣṭhā are (when they can be distinguished) intricate brahmanical rituals as well as the immersion or pervasion of deities within physical objects. Like nyāsa, these actions share conceptual territory with āveśa in that they engage positive forces (viz. deities), are induced by the performers, and are highly regulated.67 Interestingly, one of the older citations of prāṇapratiṣṭhā is from the Brahmāṇḍa, Purāṇa (3.30.4; fourth to tenth centuries C.E.),68 where it refers to the restoration of life to a corpse. Generally, however, it involves rites that infuse life breath and open the eyes of a deity. This transformative process occurs in both Sanskritic and non-Sanskritic ritual.69 An example from a recent ethnography of Tamil possession states: “Periyānṭavar’s divine essence (murtiharam) is transferred to the earthen body through an ‘eye opening rite’ (kaṇ tiṟappu). Beyond a cloth screen a musician paints with black charcoal the pupils of the god’s bulging eyes. When a camphor flame is waved before his face, the crowd cheers ‘Kovintā! Kovintā!’ the cry that always greets the reincorporation of gods in human bodies.”70 This cry, “Kovintā! Kovintā!” (Govinda, Govinda), is common in Tamilnadu when possession is invoked.71

It is not irrelevant, especially given the discussions in Chapter 11, to mention that practices startlingly similar to nyāsa occur elsewhere in Asia. In China, such practices were an important component in Daoist meditation. Isabelle Robinet notes: “Before reciting a sacred text, the adept concentrates himself by calling the deities of the four horizons and by naming and summoning the spirits of his various body parts (his face, members, and viscera). It is necessary that the divine bodily spirits fix or stabilize his body and stabilize themselves within the body.”72 One of the most spectacular of Daoist practices is meditation on the stars, particularly the Big Dipper (which the Chinese call the “Northern Bushel”). In this meditation, the stars are made to descend into the practitioner’s body, after which the practitioner reciprocates and ascends onto the stars. Robinet writes, “before stepping on the dipper,” the adept “must dress himself with stars.” Each star of the Dipper is visualized and “invoked one after the other … and made to enter into, after each invocation, a bodily organ. After this is accomplished, they enlighten the whole body.”73 The repercussions of such practices on notions of the self in China, discussed below, resemble those in India.74

Also relevant is the frequent attestation of āveśana (entrance, possession) in both Buddhist texts and classical Sanskrit lexicons, in the sense of śilpiśālā (factory, workshop, cottage industry, or sculpture studio).75 This suggests that the nature of artistic creation was regarded as an invocation or pervasion of ordinary material by positive, if not divine, forces. Āveśa, āveśana, and related notions such as nyāsa and (prāṇa-)pratiṣṭhā indicate a more attendant premeditated and performative context than do instances of praveśa, grahaṇa, and other evolutes of possession. Āveśana, like āvesa, indicates a positively charged immersion, a state of absorption in which, rather ironically, the one possessed instigates the possession. This combination of positive with apparent externally imposed possession is unusual, but must be explained by regarding the created image as uniquely capable of attracting the deity, and so on, which ultimately settles into it.

Tantric or Vajrayāna Buddhism spread from North India, Kashmir, and Nepal into Tibet between 500 and 1000 C.E., as many scholars have shown. It was then enhanced in Tibet by the indigenous Bön and other local cults and cosmologies and by the spectacular environment that is Tibet, all of which have conferred on it a unique position among the various versions of Asian Buddhism. Among the unique features of Vajrayāna Buddhism is the importance of initiations, a legacy of the Śaiva traditions of Kashmir and northern India. It was not simply a matter of taking refuge in the Three Jewels—the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Saṇgha—but of receiving initiation into the practice of multiple Buddhist deities and maṇḍalas. Indeed, the path as conceived by Vajrayāna Buddhism was fueled by initiations. This is not to discount the complexity of tantric Buddhist doctrine, the subtle layerings of Buddhist philosophical thought, the profound sectarian differences, the importance of assiduous practice, or the complex relationship between lay Vajrayāna and monastic practice and institutions. But it was initiation—infusions of divine energy delicately forged by detailed attention to ritual—that motivated the remaining aspects of Vajrayāna Buddhism.

An opportune, though admittedly uneasy, comparison may be made with the Mahābhārata. Bearing in mind that the latter is a single (if multi-authored)76 text, albeit a gigantic all-encompassing epic, while Vajrayāna Buddhism is a complex and far-reaching religious system, we must recall an observation made earlier: that the plot of the MBh is consistently advanced through curses and boons, acts of divine intervention, possession, odd synchronicities, and other extraordinary occurrences. If the Vedānta, Sāṃkhya, Dharmasāstra, and other palimpsests of orthodoxy were stripped away (even from the critical edition), a mythic series of miracle tales, some wondrous, some horrific, would be most of what remains of the MBh.77 At the risk of oversimplifying, I might say that in the case of Vajrayāna, if the yāna were stripped away, what would remain is the vajra. By this I mean tales of innumerable saints, such as Padmasambhava, Nāropa, Saraha, and Milarepa, arduous pilgrimages to far-flung places such as Kailāśa and Mānasarovara, devotionalism with powerful resonances in South Asia, and yogic siddhis. But most prominent as vajra are the initiations. We can see from the following brief extract that these have obvious points of resonance with Śaiva śaktipāta initiation described by Abhinavagupta in the Tantrāloka.78

The passage is a translation from the Vajrabhairava abhiṣeka as compiled initially by the seventh Dalai Lama, based on Indian sources. Also included is a brief section from this Dalai Lama’s autocommentary in which he quotes Nagabodhi’s description of the signs of āveśa.79

Expunge [obstructers] with: oṃ hrīṃ śrīṃ vikṛtānana hūṃ phaṭ.

Purify into emptiness with: oṃ svabhāvaśuddhaḥ sarvadharmaḥ svabhāvaśuddho ’ham.

Think the following: From emptiness I myself become the syllable hūṃ; I myself, the syllable, become a vajra marked with hūṃ; I myself, the vajra, become the great Vajrabhairava; my body is dark blue with one face and two arms holding in my hands a goad and skull bow; I stand with my left foot extended. On the crown of my head from baṃ arises a circular white water-shape marked with a vase; on that shape is haṃ. At my heart from laṃ arises a square yellow earth-shape marked at its corners with three-pronged vajras; on that shape is huṃ. At my navel from raṃ arises a red triangular fire-shape, intense and blazing; on it is āḥ. Under my feet from yaṃ arises a bow-shaped, rippling blue wind-shape, its two far corners marked with pennants; on it is jhaiṃ, in a fierce and unbearable form. Agitated by the wind, the jhaiṃ ascends to the lotus of fire at the navel; again due to the wind’s agitation, the earth at the heart begins to blaze, and from the water at the crown a stream of nectar falls; it completely satisfies me. Chant: oṃ hrīṃ śrīṃ vikṛtānana hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ / āveśaya sthambhaya / ra ra ra ra / cālaya cālaya / hūṃ haṃ jhaiṃ hūṃ phaṭ //80 As a result of saying this many times, the wisdom [beings] enter. At that time, with the visualization of it being thrown by the wind and with firm deitypride in Guru Vajrabhairava, one should brandish the vajra with the right hand, ring the ghaṇṭa [bell] with the left, and properly scent [oneself?] with incense. Visualize that the light-rays of the fire in one’s body spread out to the ten directions and invite all the buddhas and bodhisattvas in the form of Mañjusri Yamāri; like rain falling, they melt into one. Then the vajra is placed on one’s head, and by saying, tiṣṭha vajra (“Stay, Vajra!”), one should make the blessing firm.

[After going through the meaning of the mantra, the Dalai Lama comments as follows]: As a result of the Wisdom beings entering in that way, the minds of the deities—i.e., the non-dual wisdom that has the nature of the first bodhisattvabhūmi and so on—actually enter the mindstream of the disciple, or else one visualizes and believes that it has done so. Thereby, the wisdom blessing has entered the disciple; this is called the “Shared [blessing]” [Tib. skal mnyam; Skt. sabhāgaḥ]. Concerning the signs that [the wisdom beings] have entered, the root Tantra of Guhyasamāja says, “… shaking and tremors …” Ācārya Nāgabodhi comments, “One should know that the signs of entrance are shaking, elation, fainting, dancing, collapsing, or leaping upward.” In the translation by Chag lotsawa, it says, “… shaking, hair standing on end …” Thus, many signs are said to arise, from leaping—to a height of one cubit, two cubits or even eight cubits—to hair standing on end, trembling and so on.

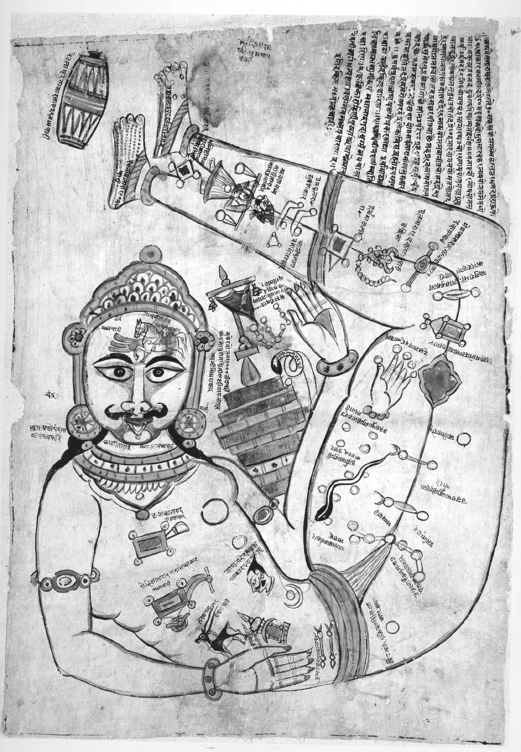

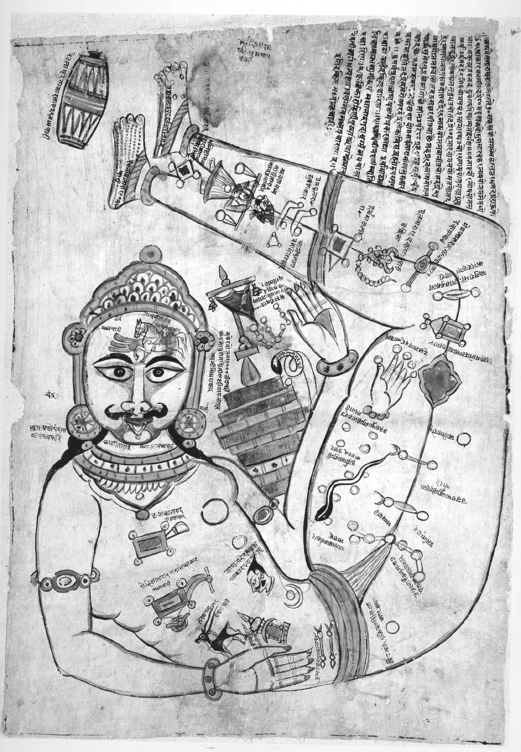

The use of long series of bija mantras, the visualization of maṇḍalas as embodiments of deities, the assertion of deities entering the initiate, and Nagabodhi’s citation of “shaking and tremors,” and so on as signs of successful initiation are familiar from Indian Śaiva initiatory sequences. We might here recall the term ātmabhāvaparigraham (taking possession of a [new] personal existence), discussed in Chapter 7, appearing in an early Buddhist text. In that text, it appeared to indicate taking on a new rebirth. Here, however, many centuries and Buddhist cultures removed, the notion of taking possession of a new personal existence is radically altered to indicate a transformation occurring in this life as a result of undertaking a powerful initiation. As one might expect, Vajrabhairava, called Vajrāveśa (“he who is possessed by a vajra”), is represented iconographically, as the image in Plate 2 attests.

This transformation is analyzed in the Kālacakratantra (KT) more explicitly in terms of possession. It is a possession strongly reminiscent of the brahmanical, liturgically actualized possession discussed earlier in this chapter. Like the brahmanical example, this discussion is situated in terms of constructing a divine body from the visualized image in a maṇḍala. Among the texts that describe such maṇḍalas are, in addition to the KT, the Vajrayāna texts Sādhanamālā and Niṣpannayogāvalī, which describe a large number of maṇḍalas to be used as meditation aids.81 These texts describe two types of beings, called samayasattva and jñanasattva. Both Stephen Beyer and Alex Wayman translate samayasattva as “symbolic being” and jñanasattva as “knowledge being.” These, says Wayman, “are among the most difficult and important ideas of the Buddhist Tantric literature.… The samaya-sattva is the yogin who has identified himself with a deity he has evoked or imagined, while the jñāna-sattva is either a human Bodhisattva, or a celestial Bodhisattva or Buddha.”82 The samayasattva, more accurately, is the visualized image of the deity, with which the meditator can identify in the “self-generation” stage of deity yoga. Beyer states that the samayasattva is “the projection upon the ultimate fabric of reality of the practitioner’s own visualization,” that the meditators visualization manipulates and “empowers the senses”83 of a jñānasattva, thus dissolving it into the figure of a samayasattva.84 This occurs through the operation of the mantra jaḥ hū ba

ba hoḥ, which summons, absorbs, binds, and dissolves the former into the latter. Beyer quotes Tsongkh’apa: “If one makes the knowledge being enter in, his eyes and so on are mixed inseparably with the eyes and so on of the symbolic being, down to their very atoms: and one should visualize their total equality.”85 It is striking how close this is to the precise physiological mirroring and pervasion that define āveśa in the yoga literature, to Vipula Bhārgava’s possession of Ruci in the MBh and to the imprinting of form and essence found in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka and Kauṣītaki Upaniṣads’ description of a moribund father entering the body of his son.

hoḥ, which summons, absorbs, binds, and dissolves the former into the latter. Beyer quotes Tsongkh’apa: “If one makes the knowledge being enter in, his eyes and so on are mixed inseparably with the eyes and so on of the symbolic being, down to their very atoms: and one should visualize their total equality.”85 It is striking how close this is to the precise physiological mirroring and pervasion that define āveśa in the yoga literature, to Vipula Bhārgava’s possession of Ruci in the MBh and to the imprinting of form and essence found in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka and Kauṣītaki Upaniṣads’ description of a moribund father entering the body of his son.

PLATE 2. Vajrāveśa (rDo-rje dbab-pa), a gate guardian (dvārapāla). His mantra is oṃ sarvavit sarvāpāyagatigahanaviśodhani hūṃ hoḥ phaṭ (Om, Omniscient One, the Deliverer from the Bonds of All evils, Hūṃ Hoḥ Phaṭ).

The image of Vajrāveśa is taken from Laxman S. Thakur, Buddhism in the Western Himalayas (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001), 115. For the mantra, see Tadeusz Skorupski, The Sarvadurgatiparisodhana Tantra: Elimination of ‘All Evil Destinies (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1983), 9, 128; cf. 93, 260–261.

The Vajratārā sādhana chapter of the Sādhanamāla describes the attraction of a jñānasattva being located in the northern part of a certain maṇḍala. The āveśa is initially induced by repetition of the syllable ra (rekāra), the same syllable prescribed for possession of Vajrāveśa.86 Then a specified pose is maintained with vajra, bell, and so on. The aspirant then installs this being on a lunar orb in the heart and worships it appropriately. The mantra jaḥ hū va

va hoḥ should be recited, says the Sādhanamālā, while performing the attracting, entering, fixing, and pleasing (ākarṣaṇapraveśanabandhanat oṣaṇam) of the jñānasattva.87 The agents in the following passage from the KT are, then, aspirants who fit the description of samayasattva.

hoḥ should be recited, says the Sādhanamālā, while performing the attracting, entering, fixing, and pleasing (ākarṣaṇapraveśanabandhanat oṣaṇam) of the jñānasattva.87 The agents in the following passage from the KT are, then, aspirants who fit the description of samayasattva.

The KT passage in question, from the abhiṣekapaṭala, the section on initiation, contains a passage on the visualization and internal manifestation of both bodhisattvas and wrathful deities (krodharāja), notably Vajrāveśa, who is emblematic in this text of the latter category. The commentator, Kalkin Śrīpuṇḍarīka, fills in important lacunae; thus the following account weaves together the KT and Kalkin’s commentarial notes. The aspirant (which the KT consistently calls śiṣya [disciple]) first prepares himself for this possession or re-embodiment by reciting the mulamantra for Vajrāveśa ten million times followed by one hundred thousand offerings with it into a fire. This mantra is: o a ra ra ra ra la la la la vajrāveśāya hū

a ra ra ra ra la la la la vajrāveśāya hū .88 Then the maṇḍala is consecrated with a long series of mantras, and the aspirant positions himself ritually, with bell and vajra in place, hands and fingers arranged in proper mudrās, suitably attired, and gifts properly distributed.89 He then declares vows of good conduct, service to gurus, buddhas, and bodhisattvas, protection of his senses, and so on. He bathes, freshens his body with scented powder, and reinforces his vows (vrataniyamayutaḥ, v. 87). He momentarily assumes earlier stages of practice (pūrvabhūmyāṃ nivesya, v. 87) by inviting and pacifying the directional buddhas and those of the external circles of the maṇḍala with the standard meditation mantra o

.88 Then the maṇḍala is consecrated with a long series of mantras, and the aspirant positions himself ritually, with bell and vajra in place, hands and fingers arranged in proper mudrās, suitably attired, and gifts properly distributed.89 He then declares vows of good conduct, service to gurus, buddhas, and bodhisattvas, protection of his senses, and so on. He bathes, freshens his body with scented powder, and reinforces his vows (vrataniyamayutaḥ, v. 87). He momentarily assumes earlier stages of practice (pūrvabhūmyāṃ nivesya, v. 87) by inviting and pacifying the directional buddhas and those of the external circles of the maṇḍala with the standard meditation mantra o āḥ hū

āḥ hū . He purifies his tongue with three mouthfuls of pañcāmṛta,90 screens off or places a cloth over these external circles of the maṇḍala (presumably to sharpen his concentration), and lights incense, which encourages possession (dhupam āveśanārtham). Then, says Kalkin Śrīpuṇḍarīka, through meditation alone he gains the ability to become possessed by the wrathful deity (smaraṇamātreṇa krodhāveśaṃ karoti).

. He purifies his tongue with three mouthfuls of pañcāmṛta,90 screens off or places a cloth over these external circles of the maṇḍala (presumably to sharpen his concentration), and lights incense, which encourages possession (dhupam āveśanārtham). Then, says Kalkin Śrīpuṇḍarīka, through meditation alone he gains the ability to become possessed by the wrathful deity (smaraṇamātreṇa krodhāveśaṃ karoti).

The next verse (v. 88), with Kalkin’s help, tells us how this deity behaves. After the deity is fully manifested within the aspirant, he is capable of killing all beings moving and nonmoving, of crushing them, by easily obstructing their progress. By threatening that host of Māras (māravṛndam), that destroyer of dharma (Kalkin glosses this as dharmaviheṭhakam), he makes them fall to the ground, immobile. Even an aspirant who does not know the proper movements is then able to perform the “vajra dance” (vajranṛtyam). He executes this dance in mid-air, thus slaying these killers of dharma, by placing his left foot forward and right foot back (pratyālīḍhādipādaiḥ). Then he laughs and sings the vajra in the form of a loud hū , which could never emanate from a human and which creates fear in this inimical host of Māras. This, then, is the nature of a wrathful deity when the practitioner is being possessed by it.