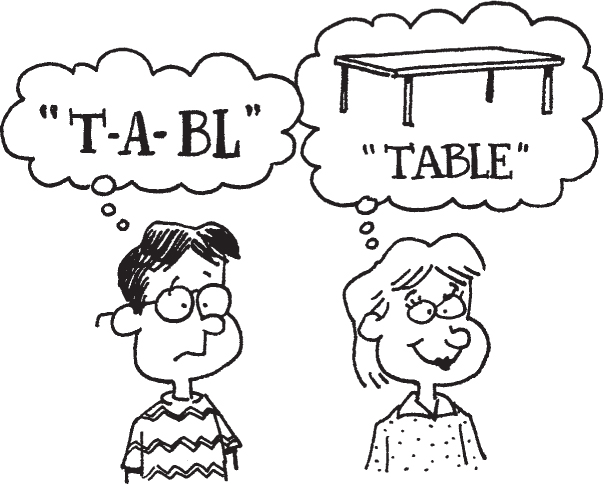

Being taught to read often is a visual-spatial learner’s first exposure to true left-hemispheric instruction. Most schools and teachers use a phonetic approach to reading. However, many visual-spatial learners learn to read using a whole word, or sight word, method. VSLs have a hard time with phonics because it breaks down words into the smallest sounds, such as: ra, ta, ga, and fa. Then, the beginning reader is supposed to build on those small sounds to form whole words. Visual-spatials understand big picture information first, not the smallest details! Because VSLs think in pictures, they need to read in pictures. What is the picture of “ga”? Or “the”? Can you create a mental picture of “the”? Do you realize there are nine different sounds just for the letter “o”? (Tot, vote, toot, book, ton, town, boy, pour, and lesson!) How does one create a picture for nine different versions of the same letter? Even more confusing is the use of “gh” as in tough, through, and hiccough!

When VSLs are taught to read by looking at whole words first, not the smallest sounds, they can make pictures for those words and learn them more easily. “Disneyland” and “xylophone” are easier to read (and spell) than “the” or “and.” There is shape and distinction to them, but not to the smaller, simpler words.

Some words just naturally make you think of a picture because of the shape the letters make (like the letters “M” and “N” do in the word MouNtaiN; see Figure 6) or because of the meaning of the word. For example, see Figure 7, a depiction of rain that uses a raindrop to dot the “i.” Your students probably can think of many more ways to draw words that include pictures. They can use different fonts that correspond with the word as described in the spelling techniques in Chapter 7. There are many words for which they cannot create a picture to represent: “an” or “the,” for example. Your students can make a picture of the word by shaping it out of string, Wikki Stix, or clay. Some schools use letters made out of sandpaper so students can trace over the shape of the letter with their fingers.

Figure 6. Student drawing of the word mountain.

Figure 7. Student drawing of the word rain.

Whole words can be placed on cards and hung from a key chain or stored in a special word box. Then, the beginning reader can practice sorting all of the words with similar starting sounds, similar ending sounds, or any other categories he or she can use to group the words. This is called analytic phonics and will help any reader improve his or her reading skills. There isn’t always a single right answer to learning something, and phonics certainly doesn’t work for every student. For more on this, please see Maxwell’s (2003) article, “Reading Help for Struggling Gifted Visual-Spatial Learners: Wholes and Patterns,” which can be found at http://www.visualspatial.org/files/wholes.pdf.

Students, especially visual-spatial students, need to be encouraged to create mental images of what they are reading for recall and comprehension. Many of them have such difficulty decoding the words that they forget to simultaneously create mental pictures. A project in Escondido, CA, called the Mind’s Eye, focused on training students to produce mental images as they read. According to the program,

training students to generate mental images as they read can substantially improve reading comprehension. Teachers or aides show students how to identify key words which will help make a mental image and encourage the children to use those words to generate images. Gains in reading comprehension from this nine-week program almost tripled prior yearly average gains. Recall was twelve times greater than previous yearly gains, and while improvements in speed and accuracy were less dramatic, those scores doubled over the previous year’s. (Pressley, 1979, as cited in Williams, 1983, p. 109)

For reading groups, I have tried the following techniques with much success. They take time but pay dividends. Authors Echevarria, Vogt, and Short (2007) wrote about The Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) Model in their work with English language learners. The same techniques that are so useful to ESL students are helpful to those who think in images, too. Here are the steps to preparing a foundation for better reading and comprehension:

➤Surveying: Scanning the text to be read for 1–2 minutes.

➤Questioning: Having students generate questions that are likely to be answered by the reading.

➤Predicting: Stating one to three things students think they will learn based on the questions generated.

➤Reading: Searching for answers to questions and confirming/disconfirming the predictions made.

➤Responding: Answering questions and formulating new ones for the next section of text.

➤Summarizing: Summarizing orally—or in pictures or words, depending on student preference—the text’s key concepts (pp. 239–240).

If your students need help remembering the pictures they are creating in their minds, they should be encouraged to keep “notes”—drawings—of what they are reading. They can do this in the margins, if the book is their own, or in a separate notebook, if it is not. Critical information, such as the plot of the story, dates of information, or names of characters they are studying, should be included in the drawings. I’ll discuss more on note taking in Chapter 8.

In his book, Gift of Dyslexia, Ron Davis wrote about a particularly successful method in helping emerging readers create mental images of what they are reading:

Picture at Punctuation is the best technique I have seen for improving comprehension skill. … When they come to a comma, period, exclamation mark, question mark, dash, colon, or semi-colon they stop reading and tell me what they are picturing in their minds about what is happening in the story. …

What makes this comprehension technique so good is it uses their strength of making mental pictures. I’m not drilling them with questions they might not be able to correctly process, I’m simply saying, “Tell me your picture.” (from J. Ringle on the techniques of Davis, 1994, as cited in Silverman, 2002, p. 292)

I have a tip for visual-spatial students about reading: speed read! Just like beginning readers have no need for the words “the,” “and,” “or,” and so on, older readers aren’t creating pictures for these words, either. So, they can just skip them. Teach them to practice running a finger, very quickly, over one line of words, then the next. They should jump right over the words that their minds don’t make a picture for. Most speed readers use their index finger to race under the lines of text as they read.

Here’s an example of how to skip pictureless words. First, read this sentence:

Then, on the following morning, Jody ran to the nearby grocery store to fetch a gallon of fresh milk for his mother.

Now, watch how much easier it is to read this sentence by skipping over the words that have no mental picture, reading only the words that create an image in your mind:

Morning, Jody ran store milk mother.

Can you do it? Can you skip the pictureless words? Was it easier? Are you missing any facts from the first sentence? Does the sentence with much fewer words still create a picture in your mind of what the character is doing, when, and for whom? You don’t even need the adjective “fresh” because you know he’s buying the milk that morning. If you are a picture thinker, it’s easier to make a mental picture when you don’t have to stop and read the pictureless words. This technique won’t affect comprehension because the reader is only eliminating the words for which there is no picture to represent, which he or she was not going to recall anyway. It actually serves to increase comprehension because now, the student can focus exclusively on creating pictures for what is being read, mental pictures that can be recalled later with increased accuracy because he or she is no longer spending frustrating study time with pictureless words.

There are plenty of hints placed in textbooks to indicate that the reader has stumbled upon important information. New words a reader is expected to recall later often are in bold print; important information often is represented in a graph, diagram, or other visual, as well as provided in the text; and subheadings often guide the reader for a good overview of the material.

One fun and effective technique for demonstrating to students how to be aware of important information within their reading is to do a “Textbook Scavenger Hunt” at the beginning of the school year. In a Textbook Scavenger Hunt, you ask students to seek general and specific information from chapters, the glossary, the index, and other areas of the book. The hunt through various chapters and other sections gives the students an overview of what the text covers and what they will be exposed to during the course of the school year. I’ve found it an excellent introduction to the material, particularly for visual-spatial learners, who can then make connections when new material is being presented. They’ll remember, for example, that the class is going to cover certain aspects of the timeline in history because they visited that chapter, however briefly, at the first of the school year. Making connections helps VSLs retain what they are hearing and reading.

When I was in school, I used to fold the corners of any pages that contained names, dates, and other important information. Today, there are many great products available at office supply stores so students don’t need to damage their books. Sticky notes in a variety of colors fill this need far better than corner folding. Teach your students to use different colored tabs for different information. For example, green tabs are for dates they must remember, blue tabs are important names, and red tabs are new words. Don’t dictate what the colors mean; rather, let each student determine what color-coding system works best. The tabs can be stuck right on the specific line of text that contains the information. Show your students how to have just the colored tab area sticking off the page for easy reference.

For students who have difficulty reading, or who read slowly, consider incorporating comic books or fantasy books with lots of visuals. Perhaps books on something that really interests the child, a favorite animal or another country, or something appealing enough to keep trying to hone reading skills. You also might consider having him or her check out recorded books from a library. Being read to enables the student to learn the vocabulary and allows the visual-spatial student to create the mental images necessary to be able to recall the story in accurate detail.

Many visual-spatial children are late readers (Silverman, 2002; West, 2004). Some have difficulty tracking a line of print. My own son surprised his teachers and parents when he was randomly selected to demonstrate a vision-tracking instrument for his school. His comprehension was significantly above grade level, and no adult in his life suspected he had a tracking issue, but it turned out that each of his eyes was reading a different line of text—simultaneously! Six months of vision therapy corrected this issue and usually does for kids with this problem. Providing books with a larger print size may be a consideration, as well. This often is easier on a student’s eyes. Some kids find reading easier when they use a colored transparency, like yellow or green, and place that over the page. Finally, there are high-interest books available from Barrington Stoke Publications that are printed on special paper using a font with an extra half space between letters that has been proven easier to read for students who are dyslexic. You can find these online at http://www.barringtonstoke.co.uk.

Other VSLs are delayed in their reading skills because they receive only phonetic instruction. However, most visual-spatial learners have a strong desire to read, particularly in their quest to learn how things work. You have the opportunity to help your beginning readers crack the code by providing visual instruction in the form of a whole word/sight word approach.