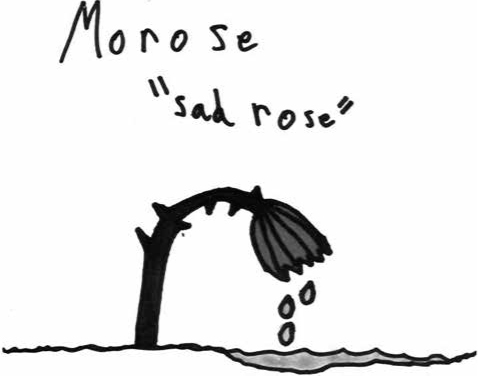

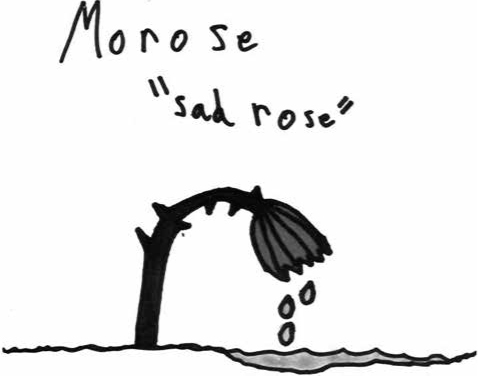

Figure 11. Student drawing incorporating the meaning and spelling of a word.

When I present to audiences, I have a Peanuts cartoon I use that shows Charlie Brown in bed thinking, “Sometimes I lie awake at night and wonder, ‘What is the meaning of life?’ Then a voice comes to me that says, ‘I before E, except after C.’” I’m sure you’ve heard and probably used this spelling rule. Who makes up these crazy spelling rules? There often are so many exceptions to the rules, it seems silly to have the rule in the first place!

For many students, visual-spatial or not, spelling is some form of torture that makes them feel less competent and can really harm their self-esteem. What other language asks you to accept (and remember) this many variations of pronouncing the same letter combination: tough, through, thorough, bough, cough, hiccough?

Many visual-spatial learners struggle with spelling (Silverman, 2002). Their gift is in creating fantastic stories using the vivid imaginations they were born with, but not necessarily in getting those stories to paper with spelling the rest of us can recognize. For generations, spelling has been taught in a sequential manner with rules that are frequently broken. One student I worked with had to repeat the word species on his spelling list week after week because he dutifully remembered that i-before-e rule and consistently misspelled it “speceis” every week! This chapter will help your students stay excited about creating stories and being able to spell correctly.

Like everything else these students learn, in order to remember the proper spelling of words, they must be taught to create permanent mental images of them. Without those pictures to see in their minds’ eyes, they’ll be trying to memorize spelling rules and all the times they are broken. And, they’ll likely fail. So, how are you going to help your students create pictures of their spelling words?

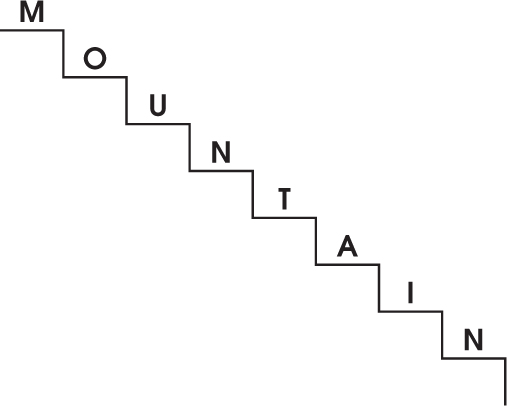

Ask students to draw a picture that includes all the letters of the word from their spelling list (or at least those they are struggling with). They should be encouraged to make up a story to go with it. Remember Figure 6 from Chapter 4 (see p. 55)? The student illustrated the word, Mountain. You can actually see mountains in the letters “M” and “N.” The characters in this student’s tale are climbing and skiing the mountain, and he made up a very creative story about why the “A” had to come before the “I” because that was something he kept forgetting to do when he tried to spell this word. His story was that the character first had to slide down the mountain, then use an “I-ce” pick (which he turned the “I” into) to climb back up. Obviously, this approach of having a character on each letter may be a bit excessive, and it’s unlikely your students would need to follow this level of detail, but you can see how imagery would help in recalling how the word is spelled. It helps to use humor or emotion, too, as those trigger the right hemisphere to engage.

Figure 11 is another example of using imagery to aid in spelling. In this instance, the student incorporated the meaning of the word into the image. When asked to recall this word, the student saw in his mind’s eye, every aspect of the image above, including the correct spelling and the definition. Incorporating color and emotion, as this example does, helps to make the image (and the spelling) permanent.

Figure 11. Student drawing incorporating the meaning and spelling of a word.

Sometimes, as in the “mountain” example discussed earlier, it’s just one part of a word that is giving a student difficulty. Whichever part of a spelling word is giving your students trouble, have them use Resource 5 for a single word at a time. They should use colored markers or crayons and write the part that they keep forgetting (in our example of mountain, that may be the “ai” combination) much larger than the other letters:

Mountain

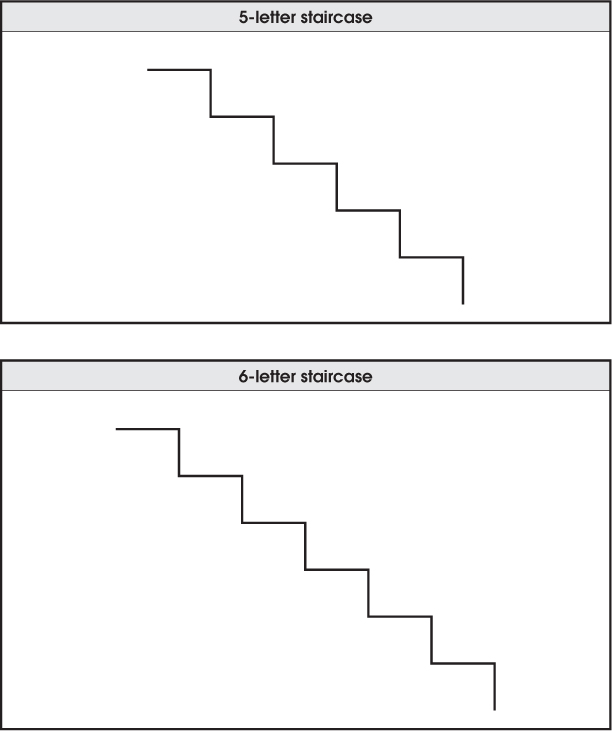

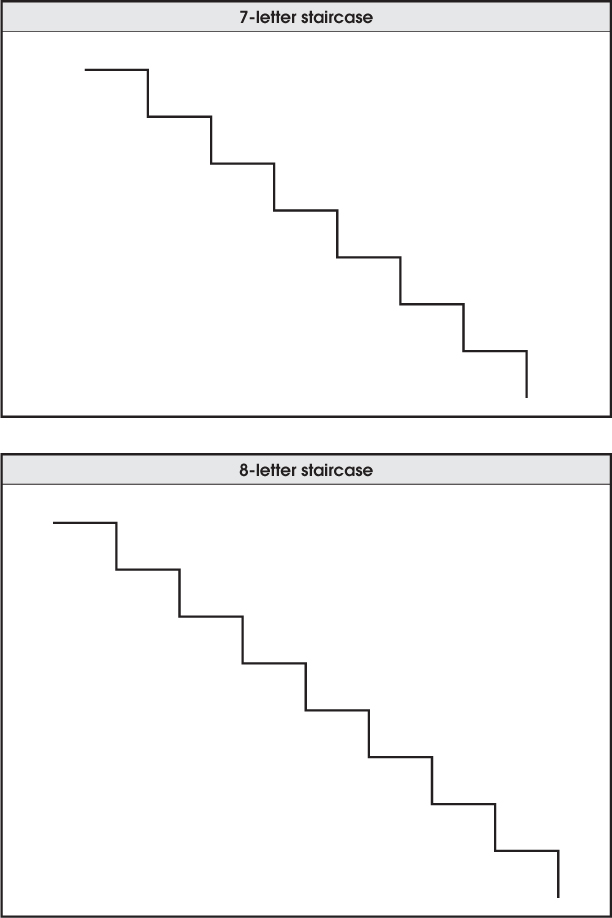

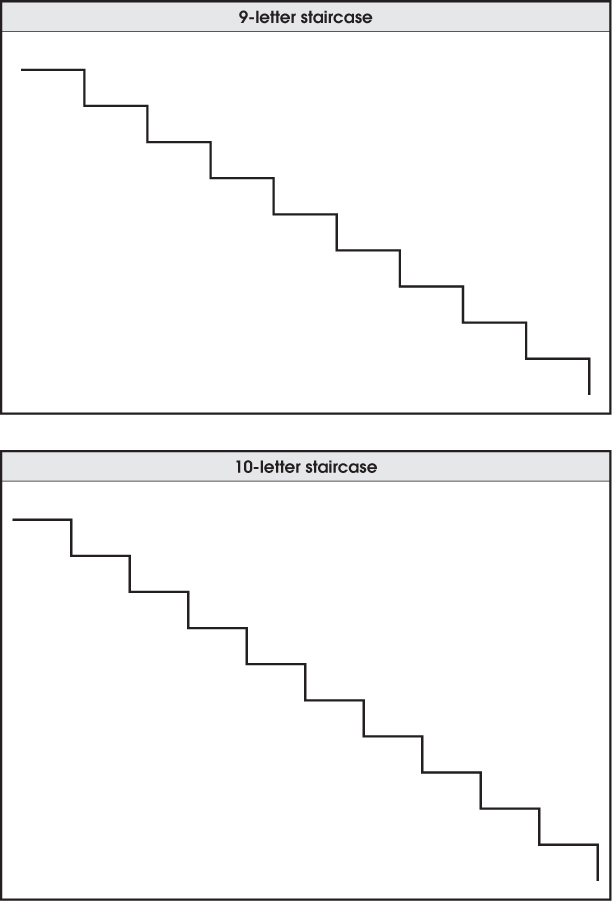

Spelling Staircases

The following staircases are for your spelling words. To prepare for your spelling test, be sure you can spell each word forward and backward!

Note. From The Visual-Spatial Classroom: Differentiation Strategies That Engage Every Learner! (pp. 65–66), by A. S. Golon, 2006, Denver, CO: Visual-Spatial Resource. Copyright 2006 by Alexandra Shires Golon. Reprinted with permission.

The use of color and/or exaggerated size is often helpful in creating a memorable image that students can easily recall. (See Strategy 7 for enhancing the use of this technique.)

In order for the right hemisphere of the brain to remember an image, it helps to have students add color, size, or humor to everything they learn (Hardiman, 2003; Jensen, 2005; Sousa, 2006; Springer & Deutsch, 2001). When students truly have a mental image of a word, they are able to see it well enough to spell it forward and backward. As you prepare your students for their next spelling test, have them spell words backward to assess whether or not they are ready for their quiz. Students who see the word in their mind’s eye can recite its spelling—either forward or backward—at the same cadence and with the same degree of accuracy.

Sometimes writing the letters of the word on stairs will help visual-spatial learners to see each letter of a word. They then climb up the stairs, mentally, to spell the word backward and climb down the stairs to spell it forward (or the other way around, if they prefer)!

Some students report great success working on their spelling lists at home where they can physically march up and down a staircase to each letter of the word. Your kinesthetic learners might appreciate this approach.

A technique that a parent in New Zealand recommended to me is to have students type each of the spelling words that are giving them difficulty in a word processing program using a different font for each word. They should select a font and color that match the feeling or mood of the word (as they see fit). Again, the ability to bring in an emotional component helps learning new material become permanent. An example might be “serendipitous,” which sounds like a fun and interesting word, and which might look like this: serendipitous. Other examples might include frightening and elegance. Students just need to be sure to use a font they can read! Adding color to the word will help to engage the right hemisphere.

There are a number of words that traditionally give students (and adults, for that matter) difficulty. One such example is “friend.” The right hemisphere is responsible for interpreting humor, and in a new learning environment, it thrives and engages when the material is funny. Here’s a silly story one student made up, and he never again forgot the correct spelling:

“These FRIes from FRIday’s sure taste good at the day’s end!”

“You’re right, FRIend!”

By using a rhyme and a double meaning on the letter combination “FRI,” he used a trick that got his right hemisphere involved in remembering how to spell this word. Metaphors and multiple meanings of words are stored in the right hemisphere of the brain.

One teacher taught her students to actually put “rule-breaking” spelling words in jail, behind bars. The word was thrown in prison for breaking the rules, and the image of the word behind bars would stick in the students’ memories. Figure 12 shows what one student did for the word reign because the “ei” combination makes a long “a” sound. It breaks another rule by having a silent “g” in it.

Figure 12. Student drawing of a word that breaks phonetic rules.

The same suggestions for using color would apply to this strategy, so encourage students to use crayons or markers to write their imprisoned letters of their challenging spelling words.

Here is an approach borrowed from neuro-linguistic programming to help create visual images for spelling words:

1.Have students write each spelling word in large print with bright-colored ink on a separate white piece of paper with the difficult part of the word written in a different color.

2.They should hold the card in front of them as far as their arm can reach, a little bit above the eyes.

3.Ask them to study the word carefully, then close their eyes and see if they can picture the word in their imaginations.

4.Now, have them do something wild and crazy to the word in their imaginations—the sillier the better. (They could make the word colorful, have the letters act as people or animals—anything that will help them remember how the word is spelled.)

5.They then place the word somewhere in space, in front of or above their heads. There is an infinite amount of space around a person that can hold an equally infinite number of words. When your students are later asked to spell the word, they will likely look to the very place they “put” it.

6.Individually, ask each student to spell their word backward with their eyes closed. Was there an even rhythm between the letters? Good! That means they are really looking at a mental picture.

7.Next, have them spell their word forward with their eyes closed.

8.Have all the students open their eyes and write the spelling word once.

9.They should close their eyes again and see if the word is still where they placed it in space. It should stay there forever!

The following is an excerpt of an e-mail I received from a parent in Australia who tried this strategy with her teenage son:

So I drew up flash cards of 5 difficult words; inherent in their difficulty was they were not phonetic, contained silent letters, or contained sounds that were not spelled phonetically. I used: Obscene, Schematic, Marmalade, Machine, Traditional.

I sat with A & told him NOT to sound these out but to just put them straight into his “TV screen.” He looked at the cards—spelt them forwards/backwards and closed his eyes and told me it was done.

I asked him to spell the 5 words. My first shock was he spelt the 5 words correctly. My second shock was when he asked nonchalantly, “Do you need me to spell them backwards to you, too?” I hadn’t expected that and told him OK—where he proceeded to spell all 5 words to me correctly … backwards!

From a boy who could barely read and was unable to spell, I started to cry. He was spelling and spelling correctly forwards and backwards. He could SEE these words. (J. M., parent from Australia, personal communication)

As I mentioned earlier, it is not unusual for visual-spatial learners to have difficulty with spelling, so I want you to consider this. Read the following paragraph. Don’t try very hard, just quickly read the words:

Aoccdrnig to rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deson’t mttaer waht oredr ltteers in a wrod apepar, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltter be in the rghit pclae. The oethr ltteers can be a cmolpeet mses and you can sitll raed the wrod!

Apaprnelty, the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter, but raeds the wrod as a wlohe. Ins’t taht amzanig? So mcuh for the ipmorancte of spleling!

Now, I know that you were able to read this because you already know how to read, and I’m not trying to suggest that a child would be able to read this. I just want you to consider that with computers and other tools available to your students, perhaps we are placing a bit too much emphasis on a proficiency that is not necessarily a life skill for their time. The paragraph above is at least something to consider the next time you administer a spelling test.

Finally, I’ll close this with a comment that spelling as a life skill may be diminishing in need. With spell checkers at everyone’s fingertips, it could be that a study in homonyms alone is sufficient. I received the following e-mail from a parent whose daughter was struggling as a speller, and I am often reminded of it when I work with parents whose children are similarly frustrated:

So, Ana (age 6) comes down tonight and she’s made herself business cards. They say:

Ana C_____, Kid Gingyus

“Genius, huh?” I say. “If you want people to take you seriously, you might want to spell ‘genius’ correctly.”

“I’m a MATH genius.”

Oh.

So, then we had this whole conversation about why the spelling of words is standardized. I say, “Sweetie, we standardize the spelling of words so that everyone can recognize the words. Think about a stop sign. Wouldn’t it be so confusing if some people spelled it ‘stup’ and some spelled it ‘stoup’ and some ‘stop’?”

And Ana says, “Mom, it’s a red octagon. Everyone knows what it means—who cares what it SAYS?”