Introduction

Introduction Introduction

IntroductionIn the sixth century BCE, an imperial archivist, philosopher, and teacher named Laozi decided to leave his declining country. Within fifty years, his homeland would be consumed as seven major and four minor states fought to conquer one another. The ensuing 254 years of intrigues and battles gave the era its name: the Warring States (475– 221 BCE).

Records tell us that Laozi, whose name literally means “Old Master,” was wise enough that Confucius himself discussed philosophy with him. Both men worked to define the right ways of living and governance. However, the two men had different approaches. Confucius believed in the rites; he wanted to bring order through a system of rigid social relationships. In contrast, Laozi believed in Tao—meaning the Way; he felt that society was intrusive and that it distorted human purity. People should instead follow a natural and simple way of life. Both men strived for peace and order even as their country fell apart. Confucius responded to this by trying to find a ruler who would put his ideas into practice. Laozi, who wrote “know when enough is enough,” withdrew from his responsibilities, mounted a water buffalo, and rode the many miles to the western border. That was the edge of the civilized world as he knew it. Only vast mountains and plains sparsely populated with nomadic tribes lay beyond the border.

At the garrison pass, a guard named Yinxi recognized Laozi. He begged the great teacher to leave a record of his wisdom. In response, Laozi wrote the Daodejing and instructed this last disciple before he rode through the fortified gates.

In that book, Laozi wrote the famous line, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” What must he have been thinking as he went into the wilderness? What compassion did he show for Yinxi, and, by extension, all who read his book, that he paused before taking this last journey? He clearly meant his words as a guide, because he knew that generations of people would follow him.

That's how we step outside each day as we journey through a world of unknowns. In this, we are not just like Laozi; we are like every human being since the beginning of our species. We walk on the same earth, where nothing else is lower or deeper than the ground. We raise our heads to the same sky above, where nothing else is higher or farther than the heavens. This is our entire world. If we are to find guidance, it will be on the road.

Each day, we feel the winds that stir the air we breathe. We drink water that flows from springs and wells, rivers and lakes. We seek heat when the weather is cold, and we cook our food over fire. When we walk, gravity anchors our bodies to this grand planet. During the day, the sun warms us, gives us the light to see, and casts the shadows that show us shape and volume. During the night, we mark the months and seasons by the moon, and we navigate by the stars. We have the same heart, breath, body, and mind as every other person we meet, as every person before us has had, and as every person after us will have. And yet, each of us is our own person, with our own feelings and ideas, and our own wills and hopes. We are both the same as everyone else and yet different.

The ancients observed this paradox. Perhaps they would put it this way: we are all human, and yet each of us has individual obligations. There are good, but not immediately apparent, ways to have a fulfilled life. Confucius and Laozi, along with the poets, philosophers, noble ones (cultivated persons), and recluses, left us their wisdom in our own searches.

The vital stream of their combined thoughts goes back to the beginnings of recorded history in China. With a calendar that began in 2637 BCE, the earliest preserved document that dates from the Canon of Emperor Yao (c. 2356– 2255 BCE), a great body of literature in the Three Teachings (Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism), and some of the best poems in the world, this stream offers us a tremendous advantage. We need only read their words.

As we examine these texts, we can't help but be conscious of the words themselves. Chinese ideographs are derived from pictures. Even abstract ideas are based on images of the world: sky, earth, water, fire, mountains, trees, river, lakes, ocean, rock, wind, plants, animals, insects, birds, people. While the language developed in complexity and extended meanings, it remained rooted in these observations. Tangibility was preferred. The writers spoke in terms of what they saw, heard, smelled, tasted, and touched. When it came time to speak of a world in constant flux, they summarized their observation with one word: Tao.*

The written word for Tao shows a person, in the form of a head, pictured as  . That symbol is combined with the sign for walking:

. That symbol is combined with the sign for walking:  . (The sign was originally written as

. (The sign was originally written as  , which is a symbol for feet.) Tao is a person walking. Since the head also represents a chief, it can also imply a person leading us on a path.

, which is a symbol for feet.) Tao is a person walking. Since the head also represents a chief, it can also imply a person leading us on a path.

Over the centuries this visual metaphor was loaded with many meanings:

Way, road, or path: This is the trail to which the leader brings us. By extension, it came to mean the trail itself. The leader may not be present, but the way remains.

Direction: Generally, you can go one of two ways on a long path. Choosing the right direction is important, and so Tao can simply refer to that.

Principle, truth, or reason: If we learn how to walk in the right direction on a good path, we'll discover the principle, truth, and reason we should walk that path. We'll learn why. When we learn why, it tells us something we can extrapolate to all paths.

Say, speak, talk, questions, commands: If leaders grasp the principles and are responsible for teaching or leading, then they have to speak, explain, persuade, ask and answer questions, and give commands.

Method, skill, steps in a process: Once principles are codified, they can be utilized and engineered. New paths are possible if one has a method. With a method repeatedly followed, skill develops.

Tao is just one word out of an estimated 23,000–90,000 characters. Most of them have multiple meanings. That makes reading, let alone translating, a delicious process of relishing many possible interpretations. We aren't reading words as if they are bricks, mortared by grammar into a single linear thought. We are viewing pictures as a collection of scenes with a web of rich associations between them.

Poetry became the ideal form for such a visual language. Freed from the restrictions of prose, Chinese poetry frequently dispensed with any subject-verb-object structure. Introductory explanations of a scene were often omitted. This keeps us in pure experience. The natural scenes become more than the setting for the story. The undeniability of nature supports the poem's truth.

When Tao is the subject, we are given the essence as quickly as possible. We are not being told of Tao. We are with the poet, seeing, hearing, and feeling the same things at the same time.

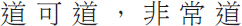

The possibilities of multiple meanings are apparent in the famous opening line of the Daodejing: “The Tao that can be said is not the constant Tao.” If you look at the original Chinese, you can see that we've had to add words to make the line intelligible. Linguistically, however, the line seems constructed to tell us a plethora of things at once, implying other possibilities.

The line can be read nearly as a mathematical formula:

Tao +

Tao +  [may, can, -able; possibly] +

[may, can, -able; possibly] +  Tao +

Tao +  [not, negative, non-; oppose] +

[not, negative, non-; oppose] +  [common, normal, frequent, regular] +

[common, normal, frequent, regular] +  Tao.

Tao.

You could insert any number of meanings for Tao into the three places where it appears in this line, combine that with any of the meanings of the other words, and make a number of reasonable interpretations. If you also consider that we approach everything with our own subjectivity, you can see why we can't demand that the poetry of Tao tell us “just one thing.” Instead, it really tells us “our thing.” It allows us to take our own meaning from the lines.

The ideographs are also symbols for sound. Spoken Chinese is a tonal language that can be lovely and melodic. Generally, each basic sound has one of five tones that are either a rising, a falling, or a neutral tone. Ritual chanting of poetic scripture was a significant form of Taoism, and it is still practiced today. For these devotees, the words have power. To possess the writings is to hold the sacred. To chant the words is to listen to Tao. To feel that resonance purifies and integrates the chanter with Tao. (Our words enchantment and chant have the same roots.)

As the culture evolved, the words took on an elevated significance. For example, nine tripod cauldrons cast from tribute bronze from nine provinces were made by order of Yu the Great (c. 2200–2101 BCE) and meticulously engraved; possessing them was considered a sign of legitimacy for subsequent dynasties. Imperial inscriptions carved into enormous stone stelae survive from as early as the third century BCE. In the Han Dynasty, the Xiping Stone Classics were installed at the Imperial Academy outside Luoyang in 175–183. The seven classics (including the Yijing) comprised about 200,000 characters, and they were carved on forty-six stelae. The poem “Climbing Xian Mountain Together with Friends” (p. 16) centers on a visit to a stela and indicates the deep admiration that was felt for such stone tablets. Even today, you can see inscriptions chiseled into the cliffs of famous sites, turning the landscapes into gigantic paintings with poetic inscriptions. The writing, which originated as pictures, took on its own presence in the world.

This brings us to the combination of Chinese painting and poetry that existed for more than a thousand years. That was made possible by the flexible but pointed brush used by craftspeople, artists, and writers alike. Literati paintings from as early as the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) were inscribed with at least one poem. If words like Tao were formed by combining two symbols, effectively creating a new metaphor, combining pictures and words extended the layers of imagery.

In the majority of cases, both the poetry and paintings remained grounded in nature. Many of the poems in this book open with a natural scene, and philosophical concepts are couched in terms of tangible things. When Laozi tells us of the central concept of nothingness, he speaks in terms of a cart wheel, a bowl, doors, and windows (p. 167). Wang Wei, who was also a devout Buddhist, may ultimately be telling us about meditation, but he opens with a leisurely description of the Massed Fragrance Temple and mountain forests (p. 81). When it comes to the paintings themselves, they are often dramatic landscapes of sheer mountains, old pines, and splashing waterfalls. There might be a traveler or a pair of friends in one corner of the painting, tiny in the vast wilderness. Usually, we're told that this represents people's insignificance in the enormity of nature. But what if this is simply a frank statement of how human beings are a part of nature, and how a person is more than a body, but is also inseparable from their surroundings? What if showing a human being is also to acknowledge their journey? To convey that, then, demanded a depiction that unified words, calligraphy, painting, and spoken language.

Let's return to Laozi, sitting in a garrison on the frontier. He wrote of the Way and its Power with ideographs that were in themselves images of the world. He made a book of pictographs that ask us to simply be present in this world. He then went into that world forever, leaving a trail of word-pictures so that we could follow.

This book looks at his words and thoughts, and then goes on to juxtapose those with many other poets who give their own views and recounted their personal experiences. Three major sources are worth mentioning. The first is the Daodejing. A complete translation of that classic is here, although it's been rearranged to alternate with other views. The second is the Yijing, particularly the section known as the Images, said to have been written by Confucius. The third is the Chinese poetic tradition itself. Many of the poets were spiritual aspirants, and their viewpoints are valuable. A large number of poems are drawn from the anthology 300 Tang Poems; many consider these poems the best in all of Chinese history. Occasionally, there are words or names of people that either will leave a person curious or have meanings that will greatly enhance the reading of a poem. A glossary and further notes about major bibliographic sources are at the end of this book.

The poems and chapters are arranged to form a journey. The first chapter, “Journey,” gives observations about the venture itself. “Beginnings” is there because every journey must start properly. “Beyond Names” reminds us that we are pursuing more than what we can label. “Yin Yang” explains the fundamental forces underlying all that we experience. Some of those experiences are sad, but the testaments of those who have gone before us is valuable; that's why we have the chapter titled “Sorrow.” Pain often turns us back to “Seeking,” and inevitably, we will reflect on the “Cycles” that lead us through both good and bad fortune.

All of that together is “Tao,” a path leading through “Heaven and Earth.” While that's the whole world, the truth about that is “Mystery.” We can best deal with that by being “Soft.” We have to pursue “Excellence.” We have to engage in “Self-Cultivation.” But what do we aim for? We aim for “Sageliness” and “Peace.” As we reach toward the spiritual, we'll understand natural effort, which is called “Nonaction.” We'll realize the power of emptiness and that it's important to realize the power of “Nothingness.” There is only the journey. There is no destination. There is only “Simplicity.”

We walk the Way each day. We don't know what's ahead, but we can follow the wisdom of others. They speak of the joys, griefs, and purity in life. Like good pathfinders, they give us direction and prepare us, and then they encourage us to walk for ourselves. Let us take their words as our companion for every step of our thousand-mile journey.

* Tao and dao are both transliterations of the same word. Tao is more recognized in English and so it is used as its own standalone term. Dao is the accurate romanization according to current but newer usage.